Sinister Scientist Wants You To Believe Nukes Are A Good Thing

“The evil villains in James Bond movies are being blamed for casting a long-lasting shadow over the image of nuclear power, says the president of the Royal Society of Chemistry. Prof David Phillips says that Dr No, with his personal nuclear reactor, helped to create a ‘remorselessly grim’ reputation for atomic energy…. Later Bond villains, as part of their cat-stroking, laser-pointing, world-destroying repertoire, also had nuclear ambitions. When there are worries about nuclear safety — such as following the tsunami in Japan — the Royal Society of Chemistry fears that the public reaction is still shaped by such emotive, negative associations.”

Apostrophe Impractical

If even bookstores are giving up on the apostrophe, does the imperiled piece of punctuation have any hope of survival?

Mary J. Blige Featuring Drake, "Mr. Wrong"

It’s rare to hear a R&B;/rap duet wherein the singing part serves as the hard side of the hard/soft dynamic. Usually it’s the other way around. But this is Drake and Mary J. Blige we’re talking about, so here we are. Now, I strongly dislike Drake. (That could be a Morrissey song, “Drake, I Dislike You.”) Even though I think he is an interesting writer and he raps well. And that makes me like this song even more.

His opening verse gives it some nice variety in texture, and there are some good things about his rhymes — good things that are, as usual, spoiled by his overall mien. He’s just so unlikeable. So smarmy and processed. And this lets Mary’s singing shine even brighter here than it might otherwise. Because she of course has one of the great, raw, naturally beautiful voices in the world. You just can’t wait ’til Drake shuts up so you can hear it.

The melody is one of the strongest ones we’ve heard Mary sing in a long time. And the beat is nice, too. Made by Jim Jonsin and Rico Love. All spare and moody. Almost like a low-key version of the beat Timbaland made for Ginuwine’s “Pony.” I mean, it’s not that nice. “Pony” is like, what? One of the top ten or fifteen beats in the past fifteen years.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=IVMKQP0K3a0

Oh, also, in case you haven’t heard, Drake is in a rap beef with Common. Which is like the time in the early ’90s when KRS-One got into a rap beef with Prince Be from P.M. Dawn. Except if instead of KRS-One it was the other guy from P.M. Dawn.

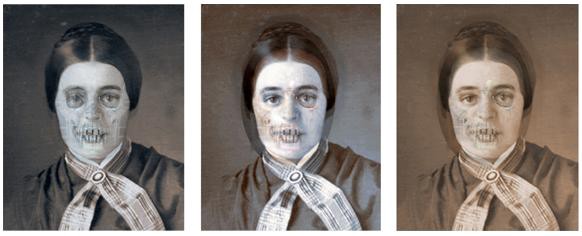

The Unfunded Art Project Inspired By Victorian Human Skulls

The Unfunded Art Project Inspired By Victorian Human Skulls

by L.V. Anderson

Sometimes, Kickstarter campaigns don’t meet their funding goals — but it’s not the end of the world! In this series, we explore what happens next.

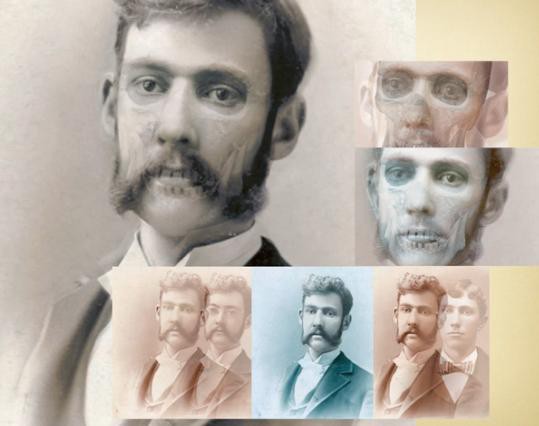

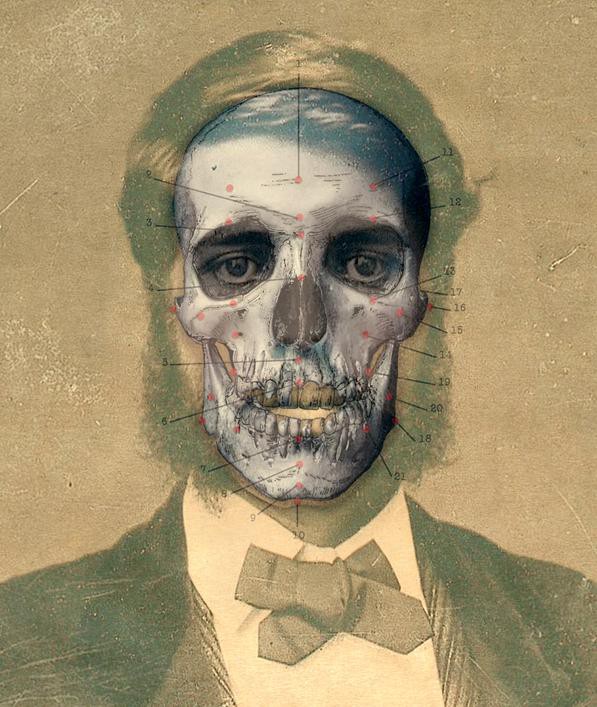

Last spring, Jeanne Kelly, a visual artist with a background in forensic art, was finishing up her MFA at Parsons in New York. She found inspiration for her thesis among the 138 human skulls that make up the Hyrtl Collection at Philadelphia’s Mütter Museum. Jeanne wanted to find out what the former owners of those skulls, collected in the late 1800s, looked like. She selected eight individuals — including a tightrope walker who died of a broken neck, a famous Viennese prostitute who died of meningitis and a Russian man who died of self-inflicted castration — researched their lives, and imagined possible intersecting narratives for them. She decided to use 3D printing technology to create small replicas of each person and put them in dioramas to tell the stories of their lives and deaths.

While working a prototype of the diorama for her thesis, Jeanne created a Kickstarter to raise money to cover the cost of the very, very expensive 3D technology and other materials. After 60 days, Jeanne had gotten pledges for only $1,511 of her $8,500 goal.

L.V. Anderson: How much research did you have to do for this project — or was it mostly fictional based on your own ideas?

Jeanne Kelly: I started with the basic facts: the actual, factual concrete little bit of narrative that each individual had. Like, we know their name, where they came from, what age they were, what their occupations were, and how they died.

I think the real trigger for me was the tightrope walker and the fact that he died with a broken neck. And instantly when you hear that, you’re like, “Oh, of course, he fell.” He’s a tightrope walker, he died of a broken neck: he fell. Our brains want to fill in the story. And we’ll fill it in with the easiest path; we will complete that line.

And the thing that’s fascinating to me about doing this project was being able to work with that but also say, “And these other things.” One of the characters is known as a child murderer; she was executed for killing her own child. When I heard “child murderer,” before I knew anything else about it, and I just read before I visited the museum that there was a child murderer in the collection, the first thing that popped into my head was a creepy old man in the corner, and no, it turned out to be an eighteen-year-old girl. And then I started thinking, “What did that mean, back in the day?” and that’s when I started to look at the time period and the place and the factual information, historically, down to what people were wearing at the time, what the interests and the politics of the region and the time were, and that sort of thing to get a clearer idea of — okay, is this a child murderer in the way that we think of, or is this possibly a woman or a teenage girl who had an abortion and was executed for murder? All of these extenuating non-facts that fit into the story.

And the rest of it was purely fiction, was purely me trying to tie them together and making them up and making it interesting and breathing life back into these harsh facts and harsh realities of these people’s lives.

I wish I could hear all of your stories, because these characters — and I know “characters” is maybe not the right word, because they were actual people — but they’re just so interesting. Even the very small amount of factual information we have about them. Like the prostitute who died of meningitis —

Right?

— and the religious guy who died because he took off his own testicles — like, what the hell? I’m sorry, but that is ridiculous, and I want to know, how does that happen?

And why, and what in the world? And like the thing with the prostitute, she was the first skull that I actually went to, because when you see these skulls in the museum, in this bank, all these rows of skulls, her skull actually stands out as quite beautiful, as morbid as that may sound. I could tell that in life she was quite stunning. Her features are slight; her cheekbones are high; she’s very symmetrical in her features, which is very important when it comes to beauty.

I know nothing about forensics stuff — can you tell me a little bit about that aspect of it and about your background in forensic art?

It’s very scientific — there’s a lot of skepticism when it comes to, how much is it art, and how much is it forensic? When it’s done for legal purposes, such as when it’s done for identification of an individual that’s been found, and is unknown, it’s very rigorous in the application of technique and the application of data. When it starts getting into the artistic aspect of it, you really have to be careful not to take any liberties. So if you don’t know for a fact that the gentleman had a mustache or any facial hair, you don’t add it, because that’s the type of thing that would prohibit someone from recognizing [the subject].

So this project was not forensic in that aspect. It wasn’t legal forensics, and it was really freeing in that way, which went back and brought back also that research that I had done on the time period. Victorians love their facial hair! So I was able to have fun with that, and so my courageous cop has a big old Victorian police officer curly mustache. It just fits; it works with him. So there were liberties I took with these reconstructions that I would never take on legal forensic reconstructions.

http://player.vimeo.com/video/22275528?title=0&byline=0&portrait=0

This kind of diorama seems so old-fashioned to me, and yet the technology that goes into it was obviously extremely cutting-edge. In your art, is that tension something that appeals to you?

It does appeal to me, and I think for me this had to be this way; I had to let the time period that these people existed in dictate the feel of how their stories were going to be presented. So that was another big part of the research: What was visual storytelling in the Victorian times? And I looked at zoetropes and stereoscopes and all these different ways that people were exploring visual narrative at the end of the 1800s, and was just really inspired by the zoetropes and by these viewing mechanisms — basically you just turn this knob really fast and it makes a movie.

The digital aspect of it is probably where my heart lies right now. I work pretty much primarily digitally, and if I could get away with making everything digital, I probably would. But it doesn’t do the work any favors; there’s no justice in that, and it’s kind of selfish to do that, so I kind of loved being able to combine those two, like analog and digital, and have it work so well. Other pieces that I work on and other things that I do, I take the same approach. Whatever the project calls for, whatever is needed, is where I’ll go. So if it needs to be a sculptural, three-dimensional box with gears and lazy Susans and 3D printed figures, so be it; that’s what it’ll be.

How did you get involved with Kickstarter?

I really decided to do it because this is the kind of project that I could not have paid for out of my own pocket. I don’t have that kind of money. When I first started and was approved for it and put everything together, I had a big talk with a few friends about, “Let’s work this budget out, and what can we do, and where can we get free materials,” and that sort of thing. I think it was $8,000, the goal that I set, and the reason that I set it that low for this project was to get one box done.

I think for me, personally, the shortcoming of Kickstarter is that you almost have to be a little bit well known, even if it’s just within your circle of art or that sort of thing, already published, already have your foot in the door in order to get the donations flowing. Or you just already have to be connected. And unfortunately, I don’t have that kind of network. I tried, I really tried, but I’m maybe not the best self-promoter.

I know the feeling. But you did get $1500, which is something.

After doing Kickstarter for the Hyrtl, a friend of mine turned me on to a funding site called IndieGoGo. And it’s not as well designed and well presented as Kickstarter is. But the one thing they do that Kickstarter doesn’t — and I understand the reasons why Kickstarter does what they do, and they’re very valid — but IndieGoGo is, basically, when you make a pledge, you make a pledge, and if you have a goal, you have a goal, and if you don’t meet the goal, you still get what is pledged, and you still owe the pledgees what you promised as rewards. It would have been nice to have that $1,500 that people had pledged, and I would have been able to still fulfill my obligations in the rewards and the thank-yous that that would require.

I like the caliber of Kickstarter, but I don’t think I’m there yet. I feel like I could do IndieGoGo a couple of time and then move up to the East Side and go to Kickstarter.

Did you know early on that you weren’t going to get all the way up to $8,000, or did you hold out hope till the end?

I tried to hold out hope till the end. I had a lot of friends of mine who, like me, don’t really have the money to have donated directly to my cause except maybe $5 here or something like that, but I had a lot of people spreading the word. So I just kept this idea in my head that, “Oh well, once the word gets out there, once I get the right kind of exposure, things will really kick off and things will really start happening and I’ll start seeing the pledges being made.” I think it was really in the last couple of weeks that I realized, “Okay, plan B. This isn’t going to happen, so what do we do now?”

So what was plan B?

Well, plan B has pretty much been I attempted to fill out some grants, and it’s really difficult with this project because it doesn’t fit into the little cubbyholes that grants open in. So after I realized I was getting denied on several grants that I applied for, I basically had to be realistic.

So the project at this point has been pretty much shelved. I don’t really have the funds or the means to work on it or do anything more with it. The reconstructions themselves, the two-dimensional reconstructions, and the actual narrative are the two aspects that I can work on, and I have been, in free time, when I’m not trying to unwind from actually working on things, I have been working on reconstructions for the other four characters. I really, really want to see Geza [a herdsman who died of old age] done, and I really want to see Francesca [the famous Viennese prostitute] done. I just want to see what these people look like. And that’s where this project started: the very selfish, “I want to see what these people look like.”

So I’ve been working on that, and where it’s at right now is just developing the narrative and creating two-dimensional prints. There are prints and print variations at the Mütter for sale now in their gift shop, and I gave a talk at Observatory in Brooklyn and sold a few prints to some of the people that came to the lecture. And that’s where it’s at right now. As much as I would love to just devote a couple of years to building these and doing this, I just don’t see it as being realistic at this point. Especially now, truly understanding, having built one prototype, really understanding what the cost of this would be.

And you’re still in the MFA program, or did you graduate?

No, I graduated in May.

Oh, congratulations!

I graduated magna cum laude!

That’s great! What have you been doing since then?

I’ve been working with a team of people on a zoetrope that I think in September — September 14th to 17th — it was installed in Union Square. It’s part of the Arts in Transit program. It’s called Union Square in Motion, and it’s a digital linticular zoetrope.

What does that mean?

It’s a linear zoetrope, meaning instead of like the old-timey zoetrope where you spin the cylinder and you look through these splits and you see a horse galloping or you see something animated, what we’ve done is flatten that out. And I know you’ve seen them in subways, when you’re in the subway cars you’re going by and there’s this animation —

Oh, yeah. I love that.

So a linticular zoetrope, what it does is, digitally we can reduce the size of the image to 1.2 inches — it’s a manipulation to the image, and then it’s digitally projected through a convex or concave lens, depending on where you’re standing and which one you’re looking at. And it’s an optical illusion; it expands the image back out at you.

There’s a vacant concession stand there, and it’s been vacant for 14 years or something crazy, so we petitioned the Arts in Transit and contacted MTA and begged, and they saw what we were doing and said, “Sure.” And we did a Kickstarter! A new project.

Oh, wow! Was it successful?

It was indeed.

Wonderful!

We weren’t asking for as much; I think we got a little over $5,000, but it was just enough to purchase the monitors, because we needed nine televisions, and we had to build these boxes to go around them, and there were hard drives and flashcards and custom lenses put in front of the monitors to get all this done, but it was just enough to do that. Well, I shouldn’t say that; we then had to chip in a couple of grand to finish up the last bits, but the big chunk of it came from Kickstarter and Kickstarter funding.

So I’ve been doing that, and I’ve been doing a little freelance, mostly like digital design for websites and some branding for a friend of mine who’s opening a pickle store: gourmet pickles. They’re amazing pickles, too; I’m sure he’s going to do amazing. So yeah, just freelancing, and being happy with that.

Previously: The Connie Converse Album That Never Got Crowd-Funded

Was your Kickstarter unsuccessful? Want to talk about it? Send us an email with a link to your Kickstarter page at kickstarted@theawl.com.

L. V. Anderson lives in Brooklyn and works at Slate. Images are copyright Jeanne Kelly.

"I'm really such a voracious reader that I'm only too grateful to get some stuff I can read."

Fans of P.G. Wodehouse will enjoy this 1975 interview with the great man, conducted a month before he passed away.

The Magnetic Fields, "Andrew In Drag"

What a great time for new music releases! Here’s the first single from the forthcoming Magnetic Fields album, Love at the Bottom of the Sea. The album is full of bells and whistles in the good way. And synths abound. Synths! [Via]

Cheap Wine Saves Lives

“In a working paper for the American Association of Wine Economists, [Cornell University economist Brad] Rickard and his team start off by looking at the states that allow grocery stores to sell wine, versus those that limit such sales to liquor stores. The increased competition of grocery stores selling wine, unsurprisingly, correlates with both lower wine prices and higher rates of wine consumption. There’s a surprising, public health benefit that grows out of that: States where wine makes up a larger part of total alcohol consumption tend to have lower rates of traffic fatalities.”

What Remains: Conversations With America's Funeral Directors

What Remains: Conversations With America’s Funeral Directors

by Max Rivlin-Nadler

Walking into McCormick Place, Chicago’s half-hangar, half-labyrinth convention center, I looked at the schedule to find that I had just missed “Canadians Do Cremation Right.” The 130th National Funeral Directors Conference, was underway; held each year in a different city, the conference brings together funeral directors from across the country for three days of presentations, trade talk, awards and camaraderie. After shaking off my initial disappointment at having missed the Canadian talk, I scanned the remaining workshops. After passing on “Marketing Your Cemetery: Connecting With Your Community” and “Managing Mass Fatality Situations,” I circled “The Difference Is In The Details,” an embalming workshop.

The small film company I sometimes work for was planning a feature on new trends in funerals, and I had flown out for the weekend to try to meet some of the younger, hipper funeral directors at the conference. One of these was Ryan, a round man with a wide smile and an impeccable hair-part, whose car, he told me, has a bumper sticker that says “Let’s Put The ‘Fun’ Back In Funeral.” He started his career as a funeral director, but had since moved into the lucrative field of “death care industry” consultation, where he works with funeral directors on ways to expand their businesses. In one of our conversations he tells me, “The worst thing I’ve heard a funeral director say is ‘we’ve always done it this way.’” Later, I tell him my plan to attend that evening’s “Funeral Directors Under 40: A Night on the Town” event. Without missing a beat, he lowered his voice and said, “Funeral directors are notoriously heavy drinkers. There will definitely be some hook-ups.”

The funeral industry is in the midst of a transition of titanic proportions. America is secularizing at a rapid pace, with almost 25% of the country describing itself as un-church. Americans, embracing a less religious view of the afterlife, are now asking for a “spiritual” funeral instead of a religious one. And cremation numbers are up. Way up. In liberal, secular states, specifically in the Pacific Northwest, cremation rates have steadily increased to more than half of disposals, up from the low single digits in 1990. The rest of the nation had also experienced steady gains in cremation since 2000 (except in the Bible Belt, where cremation rates remained relatively low). The rate of cremation has skyrocketed as Americans back away from the idea that Jesus will be resurrecting them straight from the grave. And so in the past twenty years, funeral directors have had to transform from presenters of a failed organism, where the sensation of closure is manifest in the presence of the deceased body, to the arbitrators of the meaning of a secular life that has just been reduced to ash. Reflecting this trend, this year’s NFDA conference was, for the first time in its history, held jointly with the Cremation Association of North America (CANA).

Talking with funeral directors at the conference, I began to realize the scope of the crisis spurred by the rise of cremation and its new importance. As one former funeral director said, “If the family wanted a cremation, we’d say ‘That’ll be $595,’ hand them the urn and show them the door. Not anymore though.” The industry is scrambling to find a way to add value-added cremation services to remain solvent.

This tension about how best to innovate was in evidence at the first presentation I attended, titled “How To Step Up Your Game.” The presenter worked for a consulting firm that specialized in business strategies and management — the funeral industry was his particular subject of expertise. He launched into his talk with a story about a recent trip to Disney World with his daughter. While walking through the park, he realized how much the funeral industry could learn from the attraction. At Disney World, every interaction had been scripted and rehearsed, down to the greetings from the custodians. Experiences are controlled. Likewise, he said, every funeral should offer the same experience for everyone, whether cremated or open-casket. If, say, the customer was having an open-casket service with a priest and an organist, there should also be a corresponding service for someone, possibly secular, who has just been cremated. If priests are no longer always present to say platitudes over the dead, funeral directors would have to develop a corresponding basic, secular service to stand in as a reverent farewell. Thus they’d take a much larger role in the memorial, acting more like mainstream event planners and offering such amenities as video tributes, arranging for music and other points of the new-age burial.

As he clicked back and forth between a picture of an old-fashioned, stuffy, sunless viewing room, replete with heavy velvet curtains and faux-gold candelabras, to the new, health-club-reminiscent Remembrance Room, it became clear: the funeral industry is being gentrified.

“No more outsourcing the healing to ministers, because that isn’t really going to work anymore,” the presenter continued. Religion answered the question of authenticity, the sense that the memorial was genuine and prescribed. The minister, God’s shepherd, was on hand to see the soul to heaven. But in a society that has grown suspicious and distant from religion, this no longer is sufficient. Now it’s up to the funeral directors to provide that sense of authenticity, of closure, a way to deal with the impossibility of understanding death. The presenter continued with a slideshow of forward-looking funeral homes: huge windows with sunlight streaming in, glossy ceramic tables holding both the urn and catered health food — they looked not unlike high-end yoga studios. As he clicked back and forth between a picture of an old-fashioned, stuffy, sunless viewing room, replete with heavy velvet curtains and faux-gold candelabras, to the new, health-club-reminiscent Remembrance Room, it became clear: the funeral industry is being gentrified. I looked around the room. The audience was incredibly diverse, which, was true of the conference overall and which makes sense: every community has its own funeral home, each with its own loyal followings, its own special services that a cross-town rival doesn’t offer. But here they were, being told to act more like Disney World, and everyone was taking notes.

***

The next morning I walked from the Loop, where my hotel was, to the conference center. The walk took me along the rebuilt parts of downtown Chicago, brimming with condos and families with young children. Essentially, all waterfront redevelopments really do look the same. And just as these upwardly mobile Chicagoans strive for a lower carbon footprint and uniform luxury housing in life, they will most likely do so in death as well. Cremation has been touted as the “green” way to depart this coil, and several biodegradable urn choices have become available, their sides ornamented with images of fire, water and earth. To compensate for the relative cheapness of cremation, funeral directors have begun adding a series of value-added services, from a string orchestra, to webcasting for distant family and friends, to a remembrance “rose-petal” ceremony for young attendees. (I never fully understood what exactly the rose-petal ceremony was, but from what I gathered kids throw rose petals into the air as each older family member says something about the deceased. Whatever it was, it looked adorable.)

The message attached to all these services seems to be: cremation is green, and if you choose something else, you’re a polluter, even in death. Funeral homes employ a host of chemicals, chief among them formaldehyde, to embalm a body. Some funeral homes either don’t have a correct method of disposal, or, if they are in a rural area without a sewage system, dispose of the carcinogenic — formaldehyde being intended for use on things that are already dead — right down the drain. In 2007, an EPA report found dangerously high levels of formaldehyde and phenol in drinking water in locations near funeral homes throughout New York state. The burial of a corpse in a metal coffin, with the embalmed body inside, deposits other chemicals in groundwater. The coffin’s metals leach into the ground, followed eventually by the chemicals used to preserve the corpses. Every graveyard may be lush and green, but when you look at its chemical makeup it starts to look like a mini-Brownfield. (Distressingly, higher rates of cancer have been found among embalmers who have to breathe in this stuff every day.)

Still, while cremation is on the rise, embalming remains the dominant form of disposal; current figures put it at over 60% the population. A table at the conference center had been set up for the National Funeral Directors Political Action Committee, which was advocating against some recent environmental regulations that could limit and fine the amount of waste associated with embalming. At one workshop I attended a funeral director said, “We’re not here to beautify anyone. We’re here to identify them.” He told a story of an older neighbor who lived across the street whose hands were always bruised because he worked at a factory. Knowing that he would one day be burying him, the director made a mental note not to use cosmetic to cover the bruises, because “that’s how he always looked.”

Meanwhile, on the floor of the trade show, the entrepreneurs were clearly betting on cremation’s continued rise in popularity. The floor held booths for hundreds of vendors, selling everything from health insurance to back hoes for grave digging. At one point during the weekend, a red ceremonial ribbon was cut and the tradeshow curtains parted to reveal a new line of hearses. But by far, the largest contingent of vendors were hawking cremation-related products: urns with Bible verses on them, urns with dolphins flipping in front of a Lisa Frank-style sunset, rings with diamonds made of ashes, and an iPhone app that lets you know the progress of a cremation. Funeral homes have to invest in the equipment that will guarantee a solvent future and the funerals-peripheral industry, always with its ear to the ground, is entering the cremation game in full-force. For $150 you can have a pendant that can be worn from the neck, filled with the ashes of loved ones trapped in decorative glass.

There are also options for our furry loved ones. As it happened, just as I approached the pet-urn section, my sister texted me to let me know her boyfriend’s cat had just died. I resisted asking what her plans for the ashes were, but was just then passing the eco-friendly cat urns, made to look like a ball of yarn. There were dog-bone urns, too. The young couple that was selling the pet-urns looked like they might have just as easily been peddling artisanal cupcakes. They told me they were sorry about the cat.

Attending this event as an outsider elicits a mixture of morbid curiosity, a confrontation with your own mortality and beliefs — and, if you are a good consumer, an eventual conclusion as to what you’d choose for your own earthly remains. I made the decision about the disposal of mine when I came across a table with degradable urns that were also tree planters. A special soil unlocks nutrients from the ashes that eventually become part of the tree itself. That sounded just about right for me, and I will probably insist on being planted somewhere pretty (until, of course, I am cut down to make a baseball bat for my great-great-grandchild, a baseball bat that I guarantee will only hit home runs).

Eventually, I reached the cosmetics section of the trade floor. Makeup, meant for corpses, was being applied by airbrush to a (still-living) elderly woman. She sat there on a stool, still and frail-seeming, eyes closed in the manner of anyone getting a makeover, as the presenter sprayed her with the makeup. No one seemed to consider this odd or in poor taste. Why would they? To those in the business of death, the distinction between the living and the dead is a simple matter of economics. Someone is much more valuable to them dead than alive, and the elderly among us are futures to be counted on for next year’s bottom line. I thought of the embalmer’s neighbor, the one with bruised hands. Who were we fooling? One day we will all die, and these people are the ones who will be paid to dispose of us. In this light, their preparation and commitment to self-improvement is both beautiful and professional.

The coffins took up the next section of the floor. As with urns, coffins are easily branded to accommodate the former personhood of the body within. “The Waldorf,” a solid mahogany coffin, is for the “Business Leader and Family Man,” its accompanying flyer features a picture of a silver-haired Wall Street executive. Other coffin styles targeted other professions: “Sovereign Realtree” for a rancher and “A Man of The Earth,” “Westmoreland” for a school librarian, who was also “An Elegant Women” and the “Prescott” for the architect who was “straightforward, honest, no frills,” but taken too soon from us. (Although I have a sneaking suspicion that the architect will have chosen cremation.) And of course there were the Major League Baseball caskets, so a Cubs fan can spend eternity celebrating that personal hell.

On the far side of the floor, past the new hearses, is where the future began. Just as Playstation 2 is sure to come out right after you’ve bought Playstation, there’s already a cooler, better, more expensive form of cremation. While cremation is technically “greener” than burial, the burning of the body still releases into the atmosphere whatever you might have embedded in you — dental fillings containing mercury, a hip replacement made of plastic. The newest, greenest thing is called “alkaline hydrolysis,” a process that uses sodium hydroxide (basically, lye) and extremely hot, highly pressurized water to rapidly speed up the process of natural decomposition. The body is placed in a large tube with a square control base (upon seeing a picture, a friend of mine commented that it looked a lot like a bong, and it kind of does), bathed in chemicals and highly pressurized, and in a few hours all that is left is liquid and ash.

Just as Playstation 2 is sure to come out right after you’ve bought Playstation, there’s already a cooler, better, more expensive form of cremation.

It’s a fledgling field, and one that already seems competitive as each of the vendors vies to become The Go-To Business for the greenest disposal possible. Speaking to one of the proprietors of one of the booths, he said, “It’s a still-developing science. I’m not going to tell you who it was” — here he motioned towards the other tables — “but some people here haven’t perfected it yet.”

On that ominous note, I left the future and returned to the present. A man tried to sell me Thanoseal (for when a cadaver I’m embalming begins to leak). I passed earrings made from cremated remains, and a pavilion devoted to pre-made video tributes (all that’s left is to insert photographs of the deceased against the background of a golf course).

While the funeral industry is mostly resistant to recessions, it’s still feeling the effects of our economic downturn. Funerals have become less lavish, and fewer people have been making down payments on “Pre-Need” services. Still, it remains an incredibly lucrative field, because its services are, eventually, inevitable. Or they are for most. On my way out I spoke with a cemetery owner who dismissively waved his hands at the booths with the funeral-related iPod apps and video tributes. He was, he said, very fond of the Quaker method for body disposal, just simply putting the body into the ground and letting it go. “They’ve been doing ‘green’ burials forever,” he told me. “I admire that.”

As I left the floor, the funeral directors were heading en masse towards the auditorium to elect officers for the next year. A girl dressed as a sunflower handed me a bag of M&M;’s and a flyer supporting a candidate, a well-dressed ringer for Jonathan Franzen, who was running for secretary. I checked in with Julie, my liaison at the conference, about my tickets for the evening’s 40 and Under social outing. She lowered her gaze in apology: “It’s all sold out.” Not even room for press? “We’d have to order another party bus.”

She gave me the address of the bar where the bus would be dropping off the directors. By the time I got there the young directors were already bedecked in fluorescent necklaces and quite comfortably soused; I didn’t see any actual hooks-ups going down, but there was an inordinate amount of touching and hugging going on in the room, so maybe that happened later. I said hi to a few of the people I’d met and listened to a few “things I accidentally said in front of the Reverend”-type jokes, but I could tell I wasn’t all that welcome. And I knew why. For the directors there, this was their one night to be with others who, just like them, live among the dead. They could feel free to have a good time, far from their hometowns, far from company who expect them to only ever comport themselves with the highest dignity and attitude of reverence.

The next day, on my flight home, I thought about how one of the people at that conference — maybe someone I had met, or maybe their son or daughter or apprentice — might be the last person to ever touch my failed body. I looked around the plane. Someone in one of these seats, snoozing, working on their laptop, will undoubtedly be tucked into a coffin or put into a cremator or even, one day, bathed in alkali by someone I just shook hands with or napped next to during the presentation on corpse hair-removal.

The truth is, I’ve never been to a funeral. I’ve been fortunate in life that only grandparents of mine have passed away — neither parent, no friends, no teachers. Each time one of my grandparents has died, I’ve been too far away to be able to attend their funerals. I wish I’d known this then, but you can now videoconference in to a funeral, and witness the remembrances and recessionals, the condolences and appreciations, all of it floating through the digital ether as you sit and watch in a living room half-a-world away.

For this type of service though you would need the Platinum Package, which would be an extra 400 dollars. But you can’t really put a price on that, can you?

Max Rivlin-Nadler is a founding editor of Full Stop Magazine. He can be reached here.

The "Culture of Positivity" is a Bummer

Some of my favorite haters — Céline, Pound, Bernhard — seem to have been exceedingly nasty people. Maybe they needed to be, or whatever, but is art worth it? Rilke skipped his daughter’s wedding because he didn’t want to lose his concentration. I say go to her wedding, make her happy, it’s just a poem, dude.

But I do admit to finding our culture of positivity a bummer. I agree with Adorno that “The common consent to the positive is a gravitational force that pulls us downwards.” Vituperation is a defense against vapidity. I live in Mississippi at the moment, where social relations are modeled on the butterslide. Everyone is very polite, and that politeness is sinister. I’ve got nothing against civility (“Among narrow puritans, this is lying; but with civilized people only civility” — Bellow, Herzog), but there is a kind of disguised animosity that forces itself on you with a grotesquely exaggerated deference. I prefer my animosity unclothed.

— Michael Robbins mounts a fresh argument against the new nice. (Questions for later: Is the New Niceness still new, or even nice? It is unclear. But the aggression in general these days is definitely too veiled.)