Is Impossible Pie Impossible?

Is Impossible Pie Impossible?

by Stephany Aulenback

A series about recipes that may seem odd or outmoded and yet we’re curious to try!

“I’m going to make an Impossible Pie today,” I announced.

“What’s an Impossible Pie?” asked my six-year-old son, just as I hoped he would for the purpose of writing this introduction. “Is it a pie that no one’s ever made before?”

“No,” I said.

I was about to go on when my husband spoke up, “Well, when you think about it, every pie is a pie that no one’s ever made before…”

There was a brief silence.

My son later guessed that an Impossible Pie must be “very, very hard to make.” But this is not true, of course — as the Betty Crocker site adamantly points out, the impossible pie is impossibly easy. You don’t need to make a crust for it. Instead, you just mix up all the ingredients together — the ingredients for the filling and the crust — and while it cooks the pie forms its own crust. But would that really work? And how would it taste?

Impossible Pie first became widely known in the 1970s when it was printed on the backs of Bisquick boxes. The Bisquick mix — you may have seen the yellow boxes in a cupboard or two growing up — was reportedly invented in 1930 by a General Mills executive who, while on a journey by train, complimented the chef in the dining car on his fresh biscuits. The chef showed him how he pre-mixed shortening with the dry ingredients of flour, salt and baking powder and kept the mixture on ice in the train kitchen so he could prepare the biscuits very quickly. When they mass-marketed the idea, General Mills replaced the shortening with hydrogenated oil so that the product wouldn’t need to be refrigerated. At first they marketed it solely as a fast way to make biscuits, but soon, in an effort to increase sales, they started suggesting that consumers use it to make a variety of other foods, including pizza dough, pancakes, dumplings, cookies and, yes, you guessed it, even pie.

According to the excellent food-history website, The Food Timeline, the origins of Impossible Pie, are shrouded in mystery, as befits such an enigmatic creation. The first Impossible Pie recipe introduced by Bisquick was a coconut one; this indicates that the recipe might have originated in the South where coconut pies have long been popular. In a 1993 Houston Chronicle article, excerpted on the site, Marcia Copeland, then the “director of Betty Crocker foods and publications,” essentially confirms this, saying “we first saw the recipe for (crustless) coconut custard pies in Southern community cookbooks.”

The coconut version must have gone over very well because soon Bisquick was suggesting all sorts of variations, both savoury and sweet, including but certainly not limited to: Impossible Peach and Raspberry Pie, Impossible Chicken Pot Pie, Impossible Pumpkin Pecan Pie, and Impossible Roast Pepper and Feta Cheese Pie. Just think of something you could put into a pie and there’s an Impossible version of it out there.

At some point, sadly, the company started to refer to the pies as Impossibly Easy Pies, as evidenced by this cookbook. And today, as mentioned, anyone visiting the Betty Crocker website will find a compendium of Impossibly Easy Pie recipes, names that lack the alchemical flair of their predecessors. One can only surmise that the marketing department became concerned that modern cooks would make the same assumption that my six-year-old did, and would be turned off by the notion of anything remotely difficult, never mind something ostensibly impossible. Maybe cooks were more willing to try the impossible in 1970. At that point, after all, the song “To Dream the Impossible Dream” was still only five years old. Or maybe the first women to try this recipe were hippies and on drugs and all impossibilities seemed wonderfully possible to them. Who knows? At any rate, the notion that a pie once called “Impossible” must now be called “Impossibly Easy” says something profound about our civilization, perhaps that it is in decline (i.e. its citizens no longer have the gumption to attempt to do remarkable, difficult things). Or, on second thought, perhaps this means that the civilization is still rising (i.e. things that were once difficult for its citizens to achieve are now a piece of cake. Or pie, as it were.) Or perhaps it is simply a sign that we are a civilization in recline, one declining to rise, one in which rest is to be valued above all else, which works with the whole aging population thing. It is clearly a sign of something. It’s just of what that is still unclear.

I had my first encounter with the Impossible Pie at a church supper last fall. (We don’t tend to go to church services but we do tend to go to their suppers.) There was a white board by the dessert table, which listed the twenty different kinds of pies on offer. There was the ubiquitous apple, there was the usual cherry, and the familiar pumpkin and the routine lemon-meringue and your garden-variety strawberry-rhubarb. My eyes glazed over as they traveled down the list of names until suddenly I saw the words “Impossible Pie.” Just seeing those two words side by side — two words I had never before seen next to each other — made my day. What kind of world-weary person wouldn’t want to taste an Impossible Pie? Just try to think of another food with such a delightful, interesting name. Or try to coin one. Let us just say: it is not easy.

(When asked if they could think of such a delightful, interesting name for a food, my son said, “No.” My daughter, age two, blinked. My husband suggested “Insidious Red Pepper Grunt” and “Zoophagous Asparagus” and “Unfortunate Walnut Omelet.” I rest my case.)

So anyway. On to the recipe. For the Impossible Coconut Pie, I used this one on the Bisquick site. Except I adapted it, by using original Bisquick instead of the gluten-free version (made with rice flour) they are currently trying to push.

IMPOSSIBLE COCONUT CUSTARD PIE

3 eggs

1 3/4 cups milk

1/4 cup butter, melted

1 1/2 teaspoons vanilla

1 cup flaked or shredded coconut

3/4 cup sugar

1/2 cup Bisquick mix

I actually used organic cane sugar instead of white sugar because that is what I had in the house. And if you are opposed to using a commerical mix but still want to try Impossible Pie (and who wouldn’t?), Wikipedia tells us that “one cup of Bisquick can be substituted by a mix of one cup of flour, 1½ teaspoons of baking powder, ½ teaspoon of salt, and 1 tablespoon of oil or melted butter.” If you’re not opposed to commerical mixes but worry about your health, there’s also a HeartSmart version of Bisquick you could use, which contains no trans fats and no cholesterol.

Preheat the oven to 350°F. Grease a 9-inch glass pie plate with a cooking spray like Pam. In a large bowl, stir together all ingredients until blended. Some other recipes I found online suggest mixing it all up in a blender; I used a little handheld mixer for the sake of ease, although the Bisquick recipe doesn’t suggest using anything more than a spoon or a fork. Pour this mixture into the pie plate. At this point I also sprinkled a great deal of the leftover coconut over the top of the pie, something that wasn’t suggested by Bisquick either. Bake for 45 to 50 minutes or until golden brown and a knife inserted in the center of the pie comes out clean.

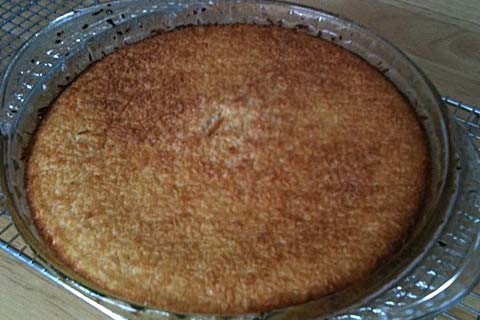

Bisquick didn’t tell us whether to serve the pie warm or cold, so I did both. The first piece I cut and served was still quite warm. The top of the warm pie looked suitably crust-like, the bottom hardly at all. After an hour or so of setting, the top still looked suitably crust-like and the bottom looked marginally more so. In both cases, the slice of pie held its pie-like shape. I have to admit, however, that as a lover of a good pie crust, there was nothing about this pie that tasted remotely pie-crust-like.

The rest of my family concurred. “Does this pie have crust?” I asked as I served it and they began to sample.

“Not really,” said Grampa. “A little on the top. But I like it.”

The others nodded in agreement.

“So would you still call it a pie, though?” I asked.

“Yes,” said Grampa, firmly.

Everyone looked surprised that I even asked, which I found odd, as doesn’t a pie get its essential pie-ness from its crust?

“Um,” said my husband.

The family ate for a moment in silence.

“Does Shepherd’s Pie have a crust?” my husband then asked rhetorically.

I shook my head. And then nodded. “Point taken,” I said.

The problem with our particular Impossible Pie’s crust might have been just that: our particular problem. Perhaps using the cane sugar made a difference in its composition. Or maybe I overmixed the batter when I used an electric mixer instead of a fork. When I googled photographs of other people’s Impossible Pies, I could see that some of the crusts were more successfully impossible than others. (This is the best one I’ve seen, and it looks admirably crusty.)

As for taste, the Impossible Coconut Pie is good, but not impossibly so. It’s sweet and custardy, tasting, very much like a mixture of coconut and eggs. I garnished my own piece with a dollop of raspberry syrup and whipped cream, which I found delicious and it looked pretty, too.

Originally, I intended to make six Impossible Pies, and all before breakfast in honour of the White Queen, but I need my sleep and, while the pies are good, they are not that good. However, I did attempt one more, a savoury one to counter the sweet, from a recipe also found on the Betty Crocker site. I followed the recipe for these Impossible Mini Cheeseburger Pies exactly and so will not reiterate here. I refuse to call them Impossibly Easy Mini Cheeseburger Pies on principle. In fact, I refuse to call them pies on principle, either, because they looked nothing like pies at any point during their creation. They looked much more like Impossible Cheeseburger Cupcakes — there was absolutely no pie-like crust in evidence but they maintained their shape beautifully — so that is what I called them.

“When I use a word,” Humpty Dumpty said, in a rather scornful tone, “it means just what I choose it to mean — neither more nor less.”

“The question is,” said Alice, “whether you can make words mean so many different things.”

“The question is,” said Humpty Dumpty, “which is to be master — that’s all.”

Through the Looking Glass.

Related: Chemical Apple Pie and The War-Rations Diet

Stephany Aulenback lives in Nova Scotia with her husband and two children. She blogs at Crooked House.

Zero of the World's Best-Designed Newspapers are American

Why Can’t Johnny Read… Attractive Newspapers? The Society for News Design has named their five most handsome newspapers (and they truly are good-looking). Look at this cool thing from Denmark’s Politiken!

The Dirty Secret of Intellectual Berlin

Przemek Pyszczek: Do you want to know the Berlin art world’s dirty little secret?

Butt Magazine: Yeah, of course I do.

P: Everyone’s obsessed with reality TV. Everyone’s watching ‘Project Runway’.

Travis Larusson: ‘Housewives’… Like e-ver-y-one.

P: We try to avoid ‘The Real Housewives of OC’ and ‘Miami’ ’cause those are busted. Like seriously. Here there’s ‘Germany’s Next Topmodel’ with Heidi Klum screaming, ‘Schlampe!’

T: Which means slut in German.

P: And, ‘Schnell, schnell!’ Faster, faster! Germans think she’s the ultimate ho. When she speaks German apparently she sounds like the biggest trashbag.

— And now you know: Berlin’s not all arguments about the impact of Gerhard Richter and “the remaking of private space.” (Link not totally safe for work but not like, nakedness on-click.)

Obama Busts Smugglers

“A small private plane carrying a load of marijuana strayed into President Obama’s no-fly zone over Los Angeles on Thursday and was forced to land at Long Beach Airport after being intercepted by U.S. Air Force jet fighters.” Oh, dudes. Always check the TFR list when smuggling drugs!

Developers Should Rejoice: Goldman Sachs Programmer Freed from Prison

I’ve always worried about the Sergey Aleynikov case. Convicted 15 months ago and sentenced to eight years in prison, Aleynikov’s crime, while employed at Goldman Sachs, was uploading chunks of software to an encrypted server for storage — possibly accidentally including proprietary code while trying to retain open-source stuff. (For a good description of what happened, there’s this account.) Some of the problems with this case include that juries and judges are crazily out of their depth in figuring out what his actions mean and which are customary and ordinary for programmers, and also the media is way worse: most of the headlines called him a “spy,” which is some pretty nutty anti-Russian sentiment, and also they keep emphasizing that the code was “proprietary software” and worth “millions of dollars.” Yeah, so is every bit of code, and none of it. Stupid! Also everyone thought it was so suspicious that this programmer was leaving Goldman Sachs for another company, with a fat salary. Um, that’s how it works? In any event: Aleynikov’s conviction has now been overturned on appeal, in the Second Circuit, with opinion still forthcoming. The decision was not based on his intentions, but, apparently, on wording of the Economic Espionage Act, so expect lots of fun garbled headlines in the near future.

Flight Attendant Bombs at Trying to Call in Sick at Work

“’The bomb on board will explode at 16.00 GMT unless our demands are met’ was reportedly written mid flight from Tokyo to London”… and a 22-year-old flight attendant has been arrested for the crime.

Gary Carter, 1954-2012

“The Red Sox were leading, 5–3, in the 10th inning of Game 6 at Shea and were one out from winning a World Series for the first time since 1918. The Mets had nobody on base. Carter kept the Mets alive with a single off reliever Calvin Schiraldi, and a pair of singles brought him home. A wild pitch allowed the tying run to score. Then Mookie Wilson hit a grounder that went between the legs of Red Sox first baseman Bill Buckner, bringing Ray Knight home with the winning run. The Mets won the World Series two nights later.”

— Gary Edmund Carter, the kid who “touched off the most memorable single-inning rally in the Mets’ history,” died Thursday of brain cancer. Carter was 57.

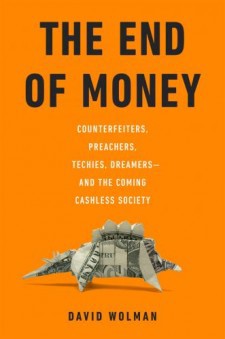

The Problem with Pennies, From 'The End Of Money'

The Problem with Pennies, From ‘The End Of Money’

by David Wolman

If pennies and nickels are largely useless, why does the U.S. Mint continue to manufacture them? In this excerpt from The End of Money: Counterfeiters, Preachers, Techies, Dreamers — and the Coming Cashless Society, out this week, David Wolman investigates why eliminating the penny is problematic.

In the Victorian ballroom of the Charing Cross Hotel in London, the thirteenth annual Digital Money Forum is wrapping up with a session of free beer and wine. Beneath brass chandeliers, people from the worlds of banking, telecom, academia, and international development have absorbed an entire weekend’s worth of talk about money in the form of bits and bytes, and tomorrow’s technologies for handling it.

I came here with high hopes, thinking it would open up a world of dazzling ideas and Star Trek–like technologies that are poised to usurp cash. But the forum proved to be just too conferencey, with its drip, drip, drip of PowerPoint presentations, impenetrable corporate jargon, and technical speak. There were a few high points, but by the tea-and-cakes break on the first afternoon, I was already feeling fidgety and uneasy. I’d lost sight of why I was here — whether it even matters, really, what form of money we use.

To get back on the cashless society track, the next morning in nearby Covent Gardens I meet technologist, ubiquitous future-of-money commentator, and self-described “anti-cash maniac” Dave Birch. Birch is the spiritual guru, organizer, and emcee of the forum. I had invited him to accompany me to the Bank of England so that I could hear him make the case against cash on its home turf.

With a gray beard and round glasses, the fifty-year-old Birch looks more like a theology professor than an electronic money and digital se¬curity expert. As we walk to the Tube station, we pass a street performer with a guitar singing Michael Jackson’s “The Way You Make Me Feel.” Birch slows to deliver a £1 coin into the man’s guitar case. “We are going to have to figure out how to do that in the digital money future,” he says.

A huge portion of the workforce, especially in the United States, depends on tips. They are real people with real jobs, often the kind that require long hours on your feet and the ability to provide service with a smile to customers undeserving of one. They are waiters, doormen, baristas, cab drivers, bartenders, strippers, and more, and it goes without saying that shunning cash for a year would be severely costly, if not impossible, for many of them.

Yet as straightforward a transaction as tipping appears — it’s just a reward for good service, right? — think about the confusion that sometimes arises when trying to figure out how much you should leave when all you had was a beer, while your friend had the ribs-and-pork combo platter. Then there’s the condition you might call Non-natives’ Tipping Anxiety. I’ve seen many friends visiting from overseas fret about whether or how much to tip, where, and when. There are even disagreements among those of us who grew up with this custom. Leave a tip for the hotel staff that tidies your room? Some say only upon checkout, others say not at all. My sister says absolutely yes, every morning of your stay. And, of course, there is the mystifying calculus for determining just how much to leave. As Benjamin Franklin is believed to have said while living in Paris: “To overtip is to appear an ass: to undertip is to appear an even greater ass.”

“Not that people even want coins,” says Birch. “Something like 40 percent of all the pennies ever issued in the UK are unaccounted for.”

The countries of Europe where wealthy Americans originally picked up the custom of tipping have long since replaced it with a more equitable and economical service tax. Should you be tempted to think that we simply must keep cash around because the generous act of tipping would become endangered without it, consider the fact that people tip more, on average, when paying with plastic. As for the street performers of the future, Birch says this is in fact a nominal obstacle, technologically speaking, on the road to cashlessness. Soon enough, we’ll be able to give someone a few dollars or pounds simply by aiming an electronic device — if not our iPhones, Androids, and Blackberries, then something similar — and pressing a few keys. “The barriers to going with digital money across the board are coming down,” he says.

We step into a coffee shop, but the queue is a dozen people deep. Birch U-turns for the exit, catching the swinging door. “I wouldn’t be a real capitalist actor if I stayed to wait,” he says, heading for another café just a block away.

The second stop is a window facing out onto the street. No line this time. Birch orders a latte to go. While fishing change from his pants pocket, he spills a handful of coins onto the curb. He pauses, staring down at the shrapnel. “There. Now you have another reason to do away with cash,” he says, before stooping his portly frame to retrieve scattered 1-pound, 50-pence, and 25-pence pieces. His expression is reminiscent of a homeowner removing someone else’s dog’s crap from the front lawn. (The metaphor has precedent: Freud ventured that there is a psychological connection between money and feces.)

“Today something like one out of every twenty £1 coins is counterfeit,” Birch says as we continue our walk through the drizzle. Those forged coins are presumably manufactured in grungy machine shops in countries like Romania and Bulgaria — someplace so poor that the economics of counterfeiting £1 coins makes sense. In the United States, we don’t have counterfeit coins. Let me rephrase that: the government’s tacit assumption is that coin-counterfeiting operations don’t exist, or don’t exist on a scale sufficient to justify the expense of looking for fakes. “Not that people even want coins,” says Birch. “Something like 40 percent of all the pennies ever issued in the UK are unaccounted for. Did you know that?” Pennies are unaccounted for because people don’t use them. The ones we get stuck with at the checkout counter usually end up lost for years in desk and bureau drawers.

The useless coinage picture is no better in the United States. The U.S. Mint has manufactured about half a trillion coins over the past generation, yet the mint itself estimates that 200 billion of them have fallen out of circulation. According to one estimate, Americans forfeit $1 billion a year due to the time spent dealing with pennies at cash registers and in wallets, when we could be doing something else, like generating income or thinking up the next Facebook. These small-change realities have compelled countries like Israel, Brazil, Australia, Finland, Argentina, and New Zealand to euthanize 0.01, and sometimes 0.05, currency pieces, while also shrinking the dimensions of their larger-denomination coins to further bring down manufacturing costs. Over the past few decades, Norway, Denmark, and Sweden eliminated all coins of value less than fifty øre (like fifty cents), and last year, Sweden’s fifty øre was the latest to get the axe. It’s an odd thing: killing money to save money. But that’s exactly what’s happening.

Pennies, nickels, and dimes can barely be described as money anymore. Legally they are, sure, but they don’t exactly circulate. A store of value? Practically nil. Medium of exchange? Only if you have a boatload of them, which won’t exactly endear you to whomever you’re transacting with. A unit of account? Technically, but I don’t know anyone who uses the hundredths place in his mental accounting. Marketing types will be quick to tell you that consumers treat $2.99 differently from $3.00, but that’s because of the hypnotic power of the left digit. No one cares about the right one anymore. It’s no wonder then that people so willingly pay the usurious 8.9 percent fee to use one of Coinstar’s 20,000 kiosks to convert unwieldy jarfuls of metal into paper money.

In the United States, the question of killing at least the penny and nickel surfaces whenever the price of metals spikes. A few years ago, the cost of making a penny peaked at 1.8 cents per cent, and nine cents for a nickel. The penny has since come down; nickels are still at about six cents apiece, while each of the new dollar coins costs an impressive thirty-four cents. “The current situation is unprecedented,” the director of the U.S. Mint told Congress in the summer of 2010. “Compared to their face values, never before in our nation’s history has the government spent as much money to mint and issue coins.” Never before has the United States faced such “spiraling” costs to issued coinage — more, in fact, than the coins’ legal tender value. “This problem is needlessly wasting hundreds of millions of dollars.”

“Absolutely anyone else would get right out of the penny and nickel business,” says Birch. At this point, you’d think the only staunch defenders of the penny and the nickel are the companies that provide the base materials, Coinstar, and politicians with a metallic sense of nostalgia or a coin-enthusiast relative. Yet a USA Today/Gallup Poll from a few years ago found that 55 percent of Americans say the penny is “useful” and shouldn’t be eliminated. Who are these people?

The $1 note has its own powerful supporters, not the least of which are employees of the money factory itself, the Bureau of Engraving and Printing (BEP). In the mid-1990s, BEP employees, under the banner “Save the Greenback,” stymied congressional efforts to phase out the $1 bill. (Paper money is cheaper than coins to produce, but it doesn’t last as long, so it’s actually more expensive in the long run.) Greenback defenders had help from Mississippi Senator Trent Lott and Massachusetts Senator Ted Kennedy, who had in mind the interests of Crane Paper of Dalton, Massachusetts, sole provider of U.S. currency paper, which is made from Mississippi-grown genetically engineered cotton. The group even proposed legislation explicitly prohibiting the elimination of the greenback, but the bill — the legislative one — never passed.

Yet there are at least a few signs that U.S. officialdom is rethinking coins. “What’s a Penny (or a Nickel) Really Worth?” was the title of a 2007 paper published by the Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago. Since medieval times, the traditional fix when minting costs surpassed the face value of the coinage was to “debase the threatened coin, that is, make it of a cheaper material.” Noting that this isn’t possible under current law, the author’s advice to Congress is to either give the Treasury the green light to find some cheaper substance for future pennies, or “discontinue the one-cent denomination and rebase pennies to be worth five cents.”

Eliminating the penny is an admission of inflation. “You just don’t do that,” a seasoned financial journalist once told me, as if I’d just suggested toppling the government. “What does a formal acknowledgement of the worthlessness of 1¢ say about the worth of $1?”

Discontinue. That is unusually decisive, if not subversive, language for a Fed official. Why? Because eliminating the penny is an admission of inflation. “You just don’t do that,” a seasoned financial journalist once told me, as if I’d just suggested toppling the government. “What does a formal acknowledgement of the worthlessness of 1¢ say about the worth of $1?” In other words, it doesn’t help the economy to remind people that prices are continually rising, while the purchasing power of their money is continually falling, even though both are true. Acknowledging inflation makes people doubt, and as any priest, rabbi, imam, or shaman will tell you, doubt and faith don’t go well together. Even though research suggests that killing the penny would benefit the economy, how can we be sure? All of a sudden, the seemingly small idea of ending pennies isn’t merely about inconvenient objects or the various uses for zinc. It’s about the whole damn economy.

We’re sensitive about inflation because higher prices are a drag, and because of concerns, rational or otherwise, that it might metastasize into something much worse: hyperinflation. This is when the purchasing power of a currency falls off a cliff, while prices rocket upward so fast that people must race to get money out of their pockets before it devalues further in the next few days or even hours. A lifetime’s savings last week can’t buy a loaf of bread this week.

The most famous example of hyperinflation hit the Weimar Republic (Germany) in the early 1920s, caused in large part by Germany’s inability to pay World War I reparations owed to its neighbors. At its nadir, the exchange rate was 4,200,000,000,000 marks to 1 U.S. dollar, and the government was printing 100,000,000,000,000-mark banknotes (yes, one-hundred trillion) in a failing attempt to keep up with rising prices. The situation was so traumatic that it helped the insane ideas of Nazism take root and fester.

Forty years since the steep inflation of the 1970s, the prices Americans interact with in daily life have remained remarkably stable relative to incomes. A cold Florida winter might bump up the cost of oranges, and the price of oil rose high enough a few years ago for President George W. Bush to acknowledge the U.S. addiction to oil, but that’s not inflation. In-your-face inflation is when you have to run down supermarket aisles, as people had to do for more than a decade in Brazil, to get ahead of the person whose job every few days was to increase the price of all the items. Younger Americans today have been so lulled by economic stability that the notion of all prices surging upward is alien. A $100 hot dog or a $10,000 sheet of plywood only reads like a typo because of our good fortune.

Still, those images from pathological instances of hyperinflation are plenty searing: banknotes used as wallpaper in Zimbabwe, swept into the gutter in postwar Budapest, or spilling out of wheelbarrows in Germany like so many leaves. One German artist during the Weimar hyperinflation covered a park bench with 100,000-mark notes. He titled the work “Deutsche Bank,” a pun on the German word for bench, which is bank. We can only pray that the same never happens here. Fears about inflation and hyperinflation may not always be rational, but countermeasures against them sure as hell are. In a roundabout way, then, maybe the wise move really is to spend whatever’s necessary to fund small coinage so as to prevent worries about inflation. What’s riskier: producing and circulating annoying coins at a loss, or injuring morale about the economy so much as to undermine faith in more than just the value of those little metal discs?

The elegant fix to all of this, of course, is to keep the denomination known as the penny — heck, even bring back the half-penny if you’re so inclined — but keep it sequestered in the cheaper and more efficient digital realm. Yet the Federal Reserve, Bank of England, European Central Bank, and most other central banks on the planet are pressing ahead with their coin orders. The next big coinage spree in the United States will be the $1 presidential series. By 2016, the Fed should have about $2 billion worth of $1 coins available, even though many merchants and cash handling companies won’t stock them because people don’t use them. Aside from those that end up stashed in collectors’ cases, the rest will gather dust in government vaults until you and I can be convinced of their utility. If you’re wondering what in God’s name these money managers are thinking, you’re not alone.

David Wolman is a contributing editor at Wired. He’s written for such publications as Outside, Mother Jones, Newsweek, Discover, Forbes and Salon. A former Fulbright journalism fellow in Japan and a graduate of Stanford University’s journalism program, he now lives in Portland, Oregon. Follow him on Twitter at @davidwolman. Excerpt from The End of Money reprinted courtesy of Da Capo Press.

Woman Falls Down

I’m sorry. I knew the woman was going to fall down — I had been told in extensive detail that how and when the woman was going to fall down and what was to be the proximate cause of her downfall — and yet, when it happened, I could not help but laugh. Which I think is the sign of a pretty good “falling down” video. Also be careful out there, kids.

A Book That Seeks to Educate Women About Losers

I’m not sure that I’m sold on this new book, but I’m DEFINITELY pro any venture that is in favor of real-talking women about straight men. People don’t break up with people enough! Go on, break up with someone today! If you love something and it doesn’t love you right back, stab it until it loves you correctly!