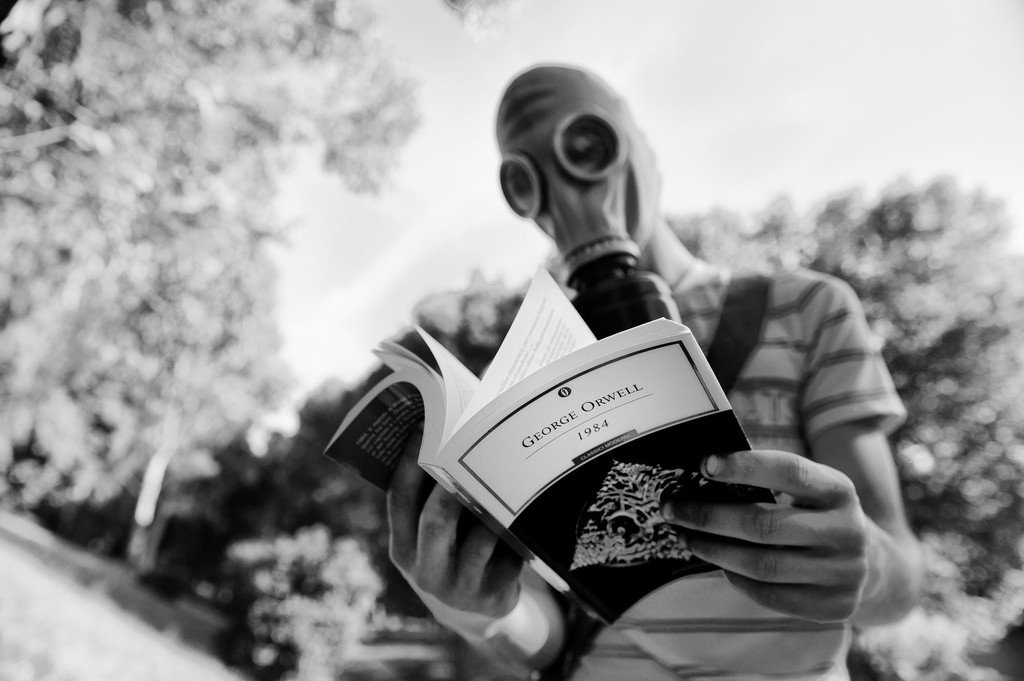

Forget '1984' -- Today, Orwell's Essays Matter More

Forget ‘1984’ — Today, Orwell’s Essays Matter More

You’ll get more from “Why I Write” than from ‘Animal Farm.’

To the surprise of absolutely no one, George Orwell is everywhere these days. His seven-decade-old dystopian classic, 1984, recently made waves by topping a bunch of bestseller lists. Orwell’s earlier (and arguably greater) allegory, Animal Farm, is also getting its due. That both novels are suddenly on the radar of people who probably haven’t given Orwell a second thought in years is hardly surprising at a time when war refugees are painted as national security threats, white nationalists hold positions of power in the White House and an American president is openly involved in an abusive relationship with the English language.

Orwell, the pen name of the Indian-born Eric Arthur Blair, speaks to us in this moment not only because he understood that words have the power both to shackle and to liberate, but also because 1984 inscribed on the literary imagination a vision of what a mass-media-fueled totalitarianism might look like. (He also envisioned what a mass-media-fueled totalitarian victory might look like — a critical aspect of the book’s plot that many people who haven’t read 1984 since high school have probably forgotten. The novel is not a manual of resistance. It is a chronicle of a crushing, obliterating defeat.)

The fact that Orwell was clear-eyed enough, meanwhile, to perceive the brute peril manifest in both Stalinism and in the fascism of a Mussolini or a Hitler provides commentators across the political divide with handy phrases to wield against their ideological foes:

All animals are equal, but some animals are more equal than others.

Big Brother is watching you.

War is peace. Freedom is slavery. Ignorance is strength.

If you want a picture of the future, imagine a boot stamping on a human face — forever.

(Recent events suggest a tasseled loafer stamping on a human face forever might be a more likely scenario.)

Regardless of how prescient Orwell’s novels might seem, his powerful, tightly argued essays remain far more relevant in our current batshit cuckoo political climate. Those readers who pick up his fiction seeking to navigate today’s fraudulent, profoundly cynical rhetoric could well miss out on the best, most concise, most penetrating writings of a man whose constant intent was to interrogate his own beliefs, while holding those in power accountable for theirs. As George Packer, the editor of two excellent editions of Orwell’s essays once put it: “In his best work, Orwell’s arguments are mostly with himself.”

Orwell was an essayist first and last. In his commentaries, columns and criticism — he wrote that the unquiet age in which he lived had forced him to become “a sort of pamphleteer”— he found something original to say about everything from the dehumanizing nature of imperialism (“Shooting an Elephant”) to Leo Tolstoy’s strange, late-in-life attack on Shakespeare (“Lear, Tolstoy and the Fool”) to the beauty and deathless vigor of the natural world (“Some Thoughts on the Common Toad”).

Ultimately, though, many of Orwell’s sharpest, most memorable essays were about the uses and abuses of language. “[O]ne can write nothing readable unless one constantly struggles to efface one’s own personality,” he declared. “Good prose is like a windowpane.” With the possible exception of “Write what you know,” that’s as compact a literary credo as one is likely to find. But succinct as it might be, it fails to acknowledge that Orwell’s prose, for all its clarity, was rarely mere glass. At various times, particularly in his essays, language assumes all sorts of roles: scalpel; microscope; mirror; weapon.

Take a passage like this one, from an essay exploring why H.G. Wells (one of Orwell’s boyhood heroes) could never grapple with the true nature of totalitarianism because he “was too sane to understand the modern world”:

Because he belonged to the nineteenth century and to a non-military nation and class … he was, and still is, quite incapable of understanding that nationalism, religious bigotry and feudal loyalty are far more powerful forces than what he himself would describe as sanity. Creatures out of the Dark Ages have come marching into the present, and if they are ghosts they are at any rate ghosts which need a strong magic to lay them. The people who have shown the best understanding of Fascism are either those who have suffered under it or those who have a Fascist streak in themselves.

That line, “creatures out of the Dark Ages have come marching into the present,” is still chilling 75 years after it was written — and not only because the modern reader is aware of the scale of the horrors about to be unleashed on Orwell’s world. (The death camps; the Red Army’s rampage of mass rape across a defeated Germany; Hiroshima and Nagasaki; anywhere between 60 and 70 million human beings killed — perhaps more — by the time WWII was over, with civilian men, women and children accounting for at least three-quarters of the dead.)

And yet how many of us have thought, in recent months, that creatures out of the Dark Ages have come marching into our present? Creatures who want women to shut up, stay home, bear children (whether they want them or not) and obey, damn it. Creatures who believe that the diktats of an unhinged leader are not only legitimate, but “will not be questioned” by the hoi polloi.

Consider this passage, from the 1941 essay, “England Your England”:

One cannot see the modern world as it is unless one recognizes the overwhelming strength of patriotism, national loyalty. In certain circumstances it can break down, at certain levels of civilization it does not exist, but as a positive force there is nothing to set beside it. Christianity and international Socialism are as weak as straw in comparison with it. Hitler and Mussolini rose to power in their own countries very largely because they could grasp this fact and their opponents could not.

A love of country — as irrational and unconditional as it might be — is a trait common to people who live in wildly different nations, with wildly different assumptions about everything from how much spice to put in one’s food to how often one should take a nap to how much a country should spend on its military. But it’s precisely because it’s a universal modern impulse that patriotism (or rather its crazy inbred cousin, nationalism) carries such force. In many countries, an intense, xenophobia-fueled patriotism is the only expression of even nominal power available to the poor, the disenfranchised, those left behind. Donald Trump and his advisers grasped this fact; his opponent did not. Or not tightly enough, anyway.

It was in the often-anthologized essay, “Why I Write,” that Orwell came closest to a distillation of his responsibilities as a politically engaged writer:

Every line of serious work that I have written since 1936 [i.e., roughly the time when he fought for the Loyalists in the Spanish Civil War, and got a bullet through the neck for his troubles] has been written, directly or indirectly, AGAINST totalitarianism and FOR democratic socialism, as I understand it. It seems to me nonsense, in a period like our own, to think that one can avoid writing of such subjects.

With that in mind one can read Orwell on Dickens (a man “who fights in the open and is not frightened … a nineteenth-century liberal, a free intelligence”) or the peculiar attitude of the English toward militarism (“English literature, like other literatures, is full of battle-poems, but it is worth noticing that the ones that have won for themselves a kind of popularity [among the English] are always a tale of disaster and retreats”) or virtually any other topic and always come away with a sense of a writer engaged in a long, long struggle to set his own ethics against the savage banalities of his age. (It’s worth noting here that, for all his combativeness, Orwell is far from a puritanical scold. One would be hard pressed, for instance, to read his unsentimental homage to the English pub in the essay “The Moon Under Water,” with its sweet, unanticipated ending, and not respond with something perilously close to “Awww.”)

Orwell never apologized for his politics — specifically, he did not apologize for being a Democratic Socialist in the postwar British vein — but instead bolstered his beliefs by exploring everything, absolutely everything, through a political lens.

So long as I remain alive and well, I shall continue to feel strongly about prose style, to love the surface of the earth, and to take a pleasure in solid objects and scraps of useless information. It is no use trying to suppress that side of myself. The job is to reconcile my ingrained likes and dislikes with the essentially public, non-individual activities that this age forces on all of us. —“Why I Write”

Orwell’s essays — more so than his novels — endure as a tonic, and an admonition: Be clear in your arguments. Be curious about the world. Above all, be skeptical of demagogues and of rhetoric grounded not in verifiable facts or demonstrable results, but in hoary appeals to blind nationalism, scapegoating and racial tribalism. “Political language,” he wrote in 1946, “is designed to make lies sound truthful and murder respectable, and to give an appearance of solidity to pure wind.” Right now is as good a time as any — and better than most — to turn from Orwell’s novels to his essays, where language itself is held to account and the only wind the reader encounters is the bracing gale of a fearless mind at work.

More Collective Nouns

For everyday use.

A passion of teachers

A sigh of poets

A swallow of psychopharmacologists

A growth of stoners

A handle of drunks

A denial of Republicans

A pyramid of polyamorous people

A table of chemists

A floss of dentists

A torture of lawyers

A tray of servers

A bubble of elites

A tempest of teapots

An armada of Mormons

A catechism of Christians

A revelation of Catholics

A query of Jews

A nirvana of clouds

A disturbance of Jedis

A box set of DJs

An encyclopedia of librarians

A cancer of smokers

A fistfight of bros

A shrug of celebrities

A hot-air-balloon of politicians

A dream of peace treaties

A disaster of wars

Josh Lefkowitz won the Wergle Flomp Humor Poetry Prize, an Avery Hopwood Award for Poetry at the University of Michigan, was a finalist for the Brooklyn Non-Fiction Prize, and won First Prize in the Singapore Poetry Contest. His poems and essays have been published at The Hairpin, The Rumpus, The Huffington Post, and many other places. He has also recorded humor pieces for NPR’s All Things Considered and BBC’s Americana.

Four Weeks Later

A reflection in verse

It isn’t just the way that there’s no limit to the lies

It isn’t just the fear that comes with every new surprise

It isn’t the audacity, the bluster and the bluff

The dumb aggressive ignorance that sells itself as tough

It’s not the chronic chaos and the basic lack of skills

It isn’t all the idiots who see these things as thrills

It isn’t the erasure of the line through “laugh or cry?”

It’s everything — and all the time — that makes you want to die

Westbound L train

Illustration: Forsyth Harmon

“It’s your favorite time!” you shouted to about twenty seven captive people, of whom I was one.

How did you know? This was my favorite time.

Months back, when I spotted those signs on the subway cars that say “Hold the pole, not our attention. A subway car is no place for showtime” I wanted to wield a Sharpie and efface them. How dare they. A subway car is exactly the place for showtime. The only place.

“Showtime showtime showtime!” you shouted as you cleared the carriage, happily shooing and clapping away passengers who shuffled off to find other poles. You were young, solo, tattooed and wore a “THRASHER” t-shirt. As you prepared your stage I noticed that I was rearranging myself a little in my seat. Sitting up a little straighter in readiness like the good audience member I was.

I love showtime like only a non-native can. To a person who moved to this city at the age of 25 from London, where making eye contact on the tube is basically illegal, the eruption of a momentary circus on public transport seemed miraculous. When it first happened I wanted to call someone. Do you know about this? These guys who do these crazy acrobatics and spin around poles and yet manage to not kick anyone in the face? I’d drink it in and think “this is so New York!” not quite knowing what I meant by that except that it was good and it was not London. I soon realized that the “the most New York” thing about it was not the spectacle itself, but the way in which almost everyone on the train would calmly ignore it. In this respect, I wish to remain a tourist.

In this freshly cleared subway car I could now see the man opposite me. He sat, dolorous, with a giant trash bag at his feet from which sprouted a shiny red helium balloon bearing a cursive message of affection. This whole edifice was fenced by haphazard plastic roses. I have always loved this day. Loved it best on the subway: everyone carrying the anxious hopes of their roses, or the monstrous, cellophane-suffocated disappointments of bears with paws sewn to plush red hearts.

Michael Jackson’s “P.Y.T.” began playing from your radio and your routine began. You spun and flipped and you were great. I put my book away to look at you. Perhaps made vulnerable by their roses and bears, everyone else looked at you too. We all wanted to love you. We clapped vigorously when you were done and as you came round a young woman looked you in the eye, placed a dollar in your baseball cap, and said, in a very deliberate and sober way: “You are very talented.”

Beside me, a vampy lady of a certain age, Cruella de Ville-ish in black-splotched white fur, turned to me with her pencilled eyebrows arched high: “He was good!” She was very surprised. I just nodded, eagerly.

Clark, "Peak Magnetic"

What day is it today?

Have you noticed that every weekday feels like a combination of Monday and Friday now? Monday because your day is filled with misery and sadness and disbelief and a perpetual, pervasive desire to be anywhere else but where you have to be; Friday because of the persistent sense that everything’s going to end shortly and the concomitant inability to focus or invest too much in anything you’re attending to — why should you, when it’s all going to be over soon? It’s no way to live and yet it may be the only life we have until the end of all our weeks comes down on our heads. The good news where you are concerned right now is that today is indeed an actual Friday, and you hopefully have the upcoming actual Monday off. The bad news is… well, everything else.

Here’s something new from Clark, whose Death Peak comes out in April, a thousand Mondays and Fridays from now. Enjoy.

New York City, February 15, 2017

★★ Morning was neither dark nor bright, neither mild nor cold. Something had wetted down the pavement and a floating dampness was the only distinguishing feature. Things brightened into a sunny and mellow afternoon. A man walked along 17th Street cradling a lacrosse stick. The blue and still-light evening sky had rain falling out of it. With the coat hood up, it was as if it wasn’t happening.

Money Trouble

Can this exploitative economic system be saved?

Now that we have decided the Enlightenment was a mistake, how long will it be before we come to the same conclusion about capitalism? As Voltaire was rumored to have said, “Sans la sauce un homme est perdu, mais le même homme peut se perdre dans la sauce.” Wise words indeed, and ones which resonate down to our very age. Anyway, here’s a long-ass piece from a recent issue of the Times Literary Supplement that takes a look at capitalism in crisis (although, to be honest, when is it not? What a drama queen, capitalism) and what is to be done.

How to save capitalism from itself

You will very surely argue against certain premises of this piece, while equally strongly asserting that other aspects are absolutely correct. Or maybe not, maybe you’re some hip young renegade who only takes time away from typing “Bernie would have won” under tweets by people you disagree with to loudly deny that there was ever any worthwhile element to capitalism. And who is to say you’re wrong? (I mean, lots of people, but whatever, if the Internet has taught us anything it’s that no one ever admits they are wrong or sticks around long enough to learn that someone has even suggested that they might be.) Either way, I want to second this review’s recommendation of Marc Levinson’s An Extraordinary Time: The End of the Postwar Boom and the Return of the Ordinary Economy, which argues that the supercharged economy from the end of World War II up until 1973 was an irreproducible anomaly and everything that anyone has tried to do to juice it since has been a bunch of economic [extreme “jerking off” motion], the failure of which has unfortunately resulted (not without help from people who have a vested interest in this being the case) in a distrust of government as an agent of social change. I am someone whose limited general intelligence and particular lack of facility with numbers means that he can only grasp simple economic concepts when described in relation to blowjobs, and even I found this book easy enough to understand; you will surely get a lot more out of it.

An Extraordinary Time: The End of the Postwar Boom and the Return of the Ordinary Economy

Alternately you could just wait for the fires to come, they surely won’t be long now. I mean, capitalism contains the seeds of its own destruction, those fuckers are sure to sprout any second, right?

The Politics of Platforms

Some shit that’s happening on YouTube, I don’t know.

It makes sense that YouTube would become home to such a performatively self-aware economy. It is, after all, one of the most mature of the major social platforms. It is extremely culturally productive, and can claim genuine stars as its own. Above all, it pays. And in the people who depend on the platform to pay their bills, it inspires a peculiar mixture of paranoia, desire, gratefulness and disdain that shows up clearly in their work. YouTube’s peculiar relationship with the economy within it is fraught, promising and poorly understood. It’s also unique among social-media platforms — but maybe not for much longer. For now, most of the biggest internet platforms are understood as venues for communication, expression and consumption. YouTube has given us a glimpse at what happens when users start associating social platforms with something more: livelihoods.

Imagine if the dinosaurs had someone who was able to explain everything about meteors to them: They would still all die, but they would be incredibly well-informed about the thing that was going to cause their extinction even as it hurtled towards them. Anyway, John Herrman is our meteor-explaining dinosaur, and here he discusses PewDiePie, which is hopefully something you don’t know a whole lot about. I mean, really, how awful for you if you do.

Why Does This One Couch From West Elm Suck So Much?

Comparing notes with other unsatisfied owners of the Peggy sofa

When I was a kid my grandma had a couch on her front porch that was, as a result of some sort of thrifty post-wartime craft project, stuffed with crumpled-up newspapers. Every couch I have sat on since then has felt unreasonably, needlessly luxurious. Poly-Fil? Foam? Goose feathers? Forget about it. The only couch anybody needs is a metal frame pulled from the curb, a few pillow cases, and a stack of old newspapers.

But in spite of myself, as a 28-year-old, I find myself drawn into the same capitalistic pitfall that many young professionals are drawn into — a need to prove my adulthood with mid-century furniture. And more specifically, a need to prove that I’ve graduated from Walmart bedframes and second-hand plywood shelves scooped up from the sidewalk.

This is why, a few weeks after moving in with my partner, Kevin, we decided to buy a couch from West Elm. The couch would be the most prominent piece of furniture in our small apartment and our first big purchase together — a gigantic spongy representation of our shared style sensibility. We chose a West Elm design called the “Peggy” in a deep rusty orange color. We would each put a fat $600 towards the couch, and that money would be an investment into our new life together. It was more than we were used to paying for a piece of furniture, but the price seemed to be proof of enduring quality. I looked at the image on the West Elm website and saw an entire montage of us laughing on the couch with friends, reading the Sunday paper on the couch, drinking obscure liqueurs on the couch (would this be the couch on which we would discover that we loved Cynar or Chartreuse?), moving the couch into a larger apartment, covering the couch with tarps while we painted the walls around it a daring color, giving birth on the couch, dying on the couch.

This is the moment when I need to warn you of something vitally important. No matter what Apple commercials and jewelry ads tell you, you should never, ever view an object as a metaphor for your relationship. Engagement rings are the biggest racket in history, and even if you love each other, one of you will lose your ring. If you buy a couch together, either the couch or the relationship will break, and the two things will have no correlation.

The couch came, and our old one, a vintage leather Craigslist number, left. We loved our new couch. It was a little uncomfortable, but probably just needed some throw pillows to soften it. We sat on the couch at the end of each day and congratulated ourselves on our good and prudent choice and searched for throw pillows that didn’t have any words or foxes on them.

Around when the throw pillows finally arrived, the couch began to disintegrate in small ways. We would scooch across a cushion at the wrong angle, and a button would pop off, leaving a fraying hole behind. We would lean back slightly too far, and all of the cushions would shift forward and over the edge of the couch in unison. As soon as one button had fallen off of our couch, it was like a spigot had been turned, allowing all of the other buttons to fall off, too. I emailed customer service and asked if this was normal. They sent me a button-repair kit, indicating that this probably happens a lot. The kit was backordered, so it arrived two full months later and contained a wooden dowel, two buttons, and some directions that didn’t make sense. One direction was to “Hold the cushion properly and make sure the pointed end of the stick is all the way through, until you can see both ends of the stick on each side of the cushion.” I tried in earnest to follow the directions, but the wooden dowel would not fit into the buttonholes, and the entire exercise left me with fewer buttons than I started with.

I became obsessed with the extremely banal mistake I had made as a consumer. You know how you’re not supposed to talk about the weather or your commute because they’re boring? The same is true of couches. The craziest fucking couch in the world is still not more exciting than the Q train running on the R line because of scheduled track maintenance. But I was obsessed, and all I could talk about was the couch. The more I talked about the couch, the more I heard from people having the same problem. It turned out that an unusually large number of our friends owned the same exact couch and were extremely miffed at West Elm about it.

For many young professionals in their 20s and 30s, the next stop after Craigslist and Ikea is West Elm. One friend, Scaachi, had bought the couch when she and her boyfriend first moved in together, just like me and Kevin. Another couple we know got the Peggy after moving into the apartment they had bought together. Everything at West Elm has the allure of being just out of the price range of recent college grads but reasonably affordable for someone who’s been saving. And with the price comes an irrational sense of faith in the furniture’s quality. Shawna Delgaty, a friend of a friend, said she was drawn to the Peggy sofa’s “affordable-but-adult” price range. “It was certainly the most money I’d ever spent on a piece of furniture,” she told me.

One friend emailed customer service after four buttons went missing, and customer service told her to hire an upholsterer. Another friend was simply told to buy a crochet needle and fix them herself. She bought the crochet needle and tried to re-thread the buttons but eventually gave up. Kevin Fanning, a friend who has a Peggy sofa with a missing button at his office, says, “The missing button (which there doesn’t seem to be any easy way to fix, short of buying a new couch) constitutes about 90% of my daily work-related frustration. Every time I look at it I lose my mind.”

Since West Elm doesn’t have product reviews on their website, there is no real reason to know how widely disliked the Peggy sofa is until you buy one and then join the strange ad hoc community of Peggy truthers on the internet. As far as I can gather, the Peggy sofa has been on the market since 2014, which means that three years of consumers have been buying it and then immediately trying to warn others against making the same mistake.

There’s the woman in Denver who left a 700-word review on her local West Elm’s Yelp page, describing why she’ll never shop there again after buying the Peggy: “To have created a detailed training guide with colored pictures on how to repair your sofa means you’ve probably received hundreds, if not thousands, of calls, emails and visits about this awfully made Peggy sofa. You have to do better, West Elm.” Another woman with similar complaints took to West Elm’s Facebook page: “I have furniture from IKEA that is 6+ years old, that has moved across the country (twice!) that has held up better than this couch.”

And then there are the Instagram Peggy trolls. Every once in awhile the couch will appear in a carefully styled photo on the company’s Instagram page, and warnings pour in under the photo. “This is literally the worst couch I’ve ever bought,” writes one commenter. Others echo: “Got this couch in gray, and it’s falling apart!!!” and “This was my first big furniture purchase and I am so disappointed.” and “This is the absolute WORST piece of #furniture I’ve ever purchased!!!”

Possessed with a fervent and slightly unhinged desire for truth and justice on behalf of the entire Peggy community, I went into two different West Elm stores and asked patient employees what they thought of the Peggy and if they would recommend it to somebody. They unanimously agreed that it was a great couch. I asked whether the buttons ever posed a problem, and one said that as long as I didn’t have pets or kids, it was fine (but here’s what a dog or a cat would look like on the Peggy in case you’re curious). In both cases, I asked what the expected lifespan is for a West Elm couch like the Peggy. Both store employees told me that between one and three years was normal for a couch with light use.

My partner tried to quell my obsession, suggesting that we buy a new one and forget the whole fiasco. But it was past the window where we could return the couch for a refund, and buying a new couch once a year sounded like the most frivolously boring way to spend money that I could think of. I would rather take an annual vacation to Iceland or join Equinox or buy $1200 of Haribo gummies every year.

On New Year’s Eve, we had a party. Twelve minutes before midnight, as a roomful of twenty or so people pounded cheap champagne and listened to the Weeknd, there was a loud crash, and the whole apartment shook. I ran out of the kitchen and into the living room. The couch had collapsed on the floor, surrounded by startled guests who were miraculously unharmed. A leg had snapped off, and the whole thing had toppled over. Tipsy friends set about propping the 300-pound piece of garbage up with stacks of books. I went to find Kevin and tell him the good news. “Happy New Year!” I said. “We’re getting a new couch.”

UPDATE: You won’t believe how this story ended.

Let Yourself Be Seduced by Saint-Saëns's 'Bacchanale from Samson and Delilah'

A thing you may or may not know about me in my life is that outside of classical music, I have straight up awful taste in music. It’s true. If there’s an EDM remix of a Top 40 pop song, I love it and I’ve probably bought it on iTunes. I think my friends quietly dread whenever I offer to send them a song I’m into, and my girlfriend has a longtime habit of calling the music I listen to “fuck music” (in the worst possible sense). Look, I’m not proud.

In turn, because it’s Valentine’s Day Week, and in vaguely apocalyptic times, people seem hornier than ever, I’d like to offer up the classic equivalent of such music, one of my all-time favorite pieces: Saint-Saëns’ Bacchanale from Samson and Delilah.

To refresh your memory, Camille Saint-Saëns was a Romantic-era composer from France. When last I wrote about Saint-Saëns, it was in reference to his Danse Macabre, a spooky little tone poem. When I was researching him back in October, I stumbled upon an anecdote about his love life that I’d like to bring forward. Saint-Saëns was married to a woman named Marie-Laure Truffot (great French name), the 19-year-old sister of one of his pupils. Saint-Saëns, for what it’s worth, was 40 at the time. The past, baby!! That said, it has long been suggested that Saint-Saëns may have been gay. Who knows, not me, certainly, though this theory did come up in the Tchaikovsky biography I read. Anyway, in 1878, three years after marrying Truffot, the two went on vacation and he bailed. Like, truly he ghosted on her. He left their hotel, where they were staying together, wrote her a letter that said “I’m never coming back,” and they never saw each other again. The past!!! Was!!! Nuts!!!!!!! I run into my exes every day of my life because, well, it’s a small city, but whatever.

What’s Spookier Than Saint-Saëns’s ‘Danse Macabre’?

The year before that, however, was the year that Samson and Delilah premiered. The Bacchanale is the big dance from Samson and Delilah, one of Saint-Saëns’ most renowned operas based, of course, on the biblical story of these two idiot lovebirds. During this scene in particular, the characters are celebrating a — guess what — bacchanale (a festival for Bacchus, who loved to drink and bone) and Samson and Delilah are slowly seducing each other. It’s sexual, trust me, opening on this very coy oboe solo.

Admittedly, one of the reasons this piece has always resonated with me is its highly percussive sound. Not unlike Shostakovich’s 5th Symphony, this also has one of my favorite timpani parts I’ve been lucky enough to play. If you listen for it relatively early on into the piece, you can hear it come in around the 2:01 mark. It just goes back and forth between two drums, but it’s key to the whole piece. It’s the heartbeat of it — the rhythm, the seduction. But even beyond that, there are some enthusiastic crash cymbals and triangle. I mean, Saint-Saëns made triangle sound sensual, kudos to him.

How I Learned To Stop Worrying And Just Listen To Shostakovich’s ‘Symphony №5’

And then about halfway through the piece, after building up to this heavy, exotic-sounding dance climax (heh), the Bacchanale switches gears around the 3:51 mark. It becomes… suddenly very sweet? Very romantic? It’s one of those scenes in a romantic movie where the couple is just so into each other that everyone else fades away. Except in this case, all of the Philistines are the ones who melt away into the background. Trust me, it works.

That moment, however beautiful, never lasts forever, and just after the 5-minute mark, the Bacchanale starts to push back into its original theme. Except, you know, this is music, so it’s that much more this time around. Including, and I know you’re rolling your eyes at me as you read this, an insanely wild timpani solo. You both do and don’t know it’s coming, but it’s exactly what you want right at the 6:24 mark.

Let me have this for a moment.

FUCK!!!!!!!!!!!!!!

The cellos and basses, of course, God bless ’em, join in with the timpani and the whole thing just rushes together in the last minute of the piece. It’s an explosion, really, of sound and texture and debauchery. It’s a full-on nightclub banger if I ever heard it; it just happened to be written in 1877.

Fran Hoepfner is a writer from Chicago. You can find a corresponding playlist for all of the pieces discussed in this column here.