Lusine, "Slow Motion"

So long, winter.

Are you ready for spring? Hahaha, too late, it already is spring. There’s nothing but warm weather ahead. And even though it’s only February I’m prepared to say that there’s no way it’s going to get cold again. No more snowstorms, no more shivering… winter is over. That’s it, we’re done. There’s nothing at all to worry about anymore! Put your heavy coats in the back of the closet and break out all your summer wear, because it’s definitely for sure never going to be cold again.

Now that that’s out of the way, let’s talk about how great the new Lusine record is. It’s pretty great! It’s called Sensoritmotor, it’s out at the beginning of March, and here’s another track from it. Enjoy.

New York City, February 20, 2017

★★★★ Sunrise brought a bright smooth spectrum to the cloudless sky. The eerie tropical warmth was off the atmosphere; it was cool and the coolness was of a piece with the clarity. Reflective beads in the yellow thermoplastic marking on the roadway glimmered through a layer of caked-on dirt. Deep shadow and bright highlights made rustic upper-story stonework look too authentically rough-hewn to be up where it was. A legion of figures helmed in blazing light advanced uptown in irregular order. A step sidways into the shade brought down a curtain that seemed to muffle the sound along with the sight. Once the sun had passed its peak, the air and the light took on the character of autumn. The synthetic fibers in the dark jackets of the police shone. An officer cautioned sun-dazed marchers not to trip on the feet of the barricades. Further down the street, where the rally was thicker, the crowd was deep in shadow. High in the distance the cranes atop unfinished ultraluxury apartments glittered. The crowd in its jacketed enthusiasm felt suddenly like the crowd on the way into a college stadium, with the whole game yet to go.

Help Desk: Fury Road

Notes from the federal government’s IT department

8:57am

The federal government’s IT Help Desk staff logged onto their computers and phones. It was that limbo period that began each workday. If someone didn’t kick off conversation, before federal government workers started calling in with their computer issues, it could make for a long, awkward shift.

“There’s so much TV now,” Gary said to no one but also to everyone.

“Are you watching ‘Peaky Blinders’ yet?” Robin asked disinterestedly.

“No. Are you watching that show on HBO?”

“You know, I always mean to but I don’t know how to stream,” Robin jotted down a note to herself to learn how to stream. Ask kids?

“It’s easy to stream. You just — ”

“I like to go to bed early on Sundays,” Cindy announced. “A Tylenol PM on Sunday nights about 7 o’clock is my one indulgence,” she said, like she didn’t keep a handle of brown liquor in her desk drawer.

“Has anyone else noticed that ever since Trump got here the questions have been less IT related and more existential in nature?” Art asked philosophically.

Everyone ignored Art because they were still mad at him for not inviting any of them to his wedding a few weeks ago, his third or fourth.

“Last week,” Art continued, “we had that data scientist from the Department of Education who had to ensure that Betsy DeVos’s personal iPad always stays connected to office wifi. And then that park ranger who tracked every bald eagle he spotted, with latitude and longitude coordinates. His new boss wanted photos, strong visuals, he said, not numbers.” Art opened his Greek yogurt and skimmed the water from the top.

“And that US Attorney who was directed to prosecute every dead person who cast a vote for Clinton. He didn’t know what good a database of dead people would do. Is that existentialism or nihilism? Neither? I haven’t used my philosophy degree in a long time.”

Gary, Robin and Cindy all exchanged glances. They hadn’t noticed what Art was referring to.

10:12am

“Fedgov Help Desk. How can I help you?” Robin asked as she picked up her phone.

“Hi. I’m at the Environmental Protection Agency and I need help. I have all these files and I want to save them after my agency is dismantled. That way if I decide I want to do the whole Calexit thing I have a template. Like why reinvent the wheel if we have a perfectly good agency already?”

“Okay, that sounds like a fairly routine task. Can you tell me who I’m speaking with?”

“My name is Gale.”

“Hi Gale. Have you considered printing them?”

“I don’t want to print them because that wastes paper, but I also don’t want to email them to my personal email because I don’t trust the administration to not be reading all my emails.”

“That’s sensible, Gale.”

“Oh fuck. Gotta go. Mike Pence is here to give us all Communion. I’ll call you back.” Gale said. “He’s early today,” she said as she hung up her phone.

12:13pm

“Fedgov Help Desk. This is Cindy speaking.”

“Hi. I found this number taped onto my monitor. I am one of the clerk typists and I need help.”

“You called the right place. What’s wrong with your computer?”

“Nothing, I don’t think? The stickie says Help Desk with this number I just called. It’s taped right on the monitor like it’s a saying from a fortune cookie.”

“Okay, well, this is the IT Help Desk. We help with, like, password resets, if you need a printer connected, if your email inbox needs more storage, that sort of stuff.”

“He said he poisoned the water cooler this morning so anyone who’s taken a drink since 10am might get really painful diarrhea. Is that IT?”

“Who is he, ma’am?”

“Steve Bannon. He’s wearing shorts today.”

“So why again are you calling the IT Help Desk?” Cindy waved Robin and Gary over. She mouthed ‘Bannon’ to them. “Is this number taped to all the computers in your office?”

“I didn’t use the same computer yesterday. We have to find a new seat every morning and we can’t sit next to the same person two days in a row. To avoid humanizing our colleagues, he says.”

Cindy opened her desk drawer and pointed to her whiskey and then to her phone. “What’s your office, ma’am? Do you work for the federal government? This is the IT Help Desk.”

“He cleared out the Office of Legal Counsel. He calls it JUG now. Justice Under God. Today we’ve been assigned to write essays about why the Federal Reserve must shrink the money supply. The winner’s essay will become the executive order and the loser’s will be leaked as fake news an hour beforehand.”

“I think I’ve heard of that,” Cindy said as she opened a work order, and began logging the caller’s information.

“I don’t even know what the Federal Reserve does, only that his t-shirt last week says it should be abolished. He wears that t-shirt or a Harvard Business School one or a Coors Light one, like one of those t-shirts you get for free when you buy something else.”

“Is there an IT problem I can help you with?”

“Can I turn my computer into a time machine, I guess?”

“What’s happening now?” Cindy began typing into her work order.

“He’s slurring his words. He has brown shit, peanut butter, all over his face. He just pulled a dog whistle out from the pocket of his cargo shorts. The German shepherds in the hallway will bark after he blows into the whistle. There must be like thirty of them out there. When they’re all barking, it’s like the world is ending or something. That’s what it feels like.”

“Oh God,” Cindy said to Robin and Gary.

“Now he’s on all four barking along with them. Like he’s really going for it, and one of the dogs is licking the peanut butter from his face. Maybe it’s dog food though, I don’t know. The dog is licking his face aggressively.”

“Can he see you? Or hear you right now?” Cindy asked. “Is this safe for you?” She looked to Robin and then to Gary and then even to Art.

“Now Stephen Miller is here and he is huffing Sharpie markers like a white collar war boy. He is handing the other Steve, older, fatter Steve, a document. It looks official. One of our essays. Here’s Kellyanne now. Steve and Stephen, she’s saying. She’s resting her head on Stephen’s shoulder, younger, skinnier Steve, but he’s not reacting. He’s just, like, breathing shallowly.”

“So they’re all at the Justice Under God office? Right now? With you?”

“She’s addressing the entire room now. Remember, when we’re leaking to the media, she’s screaming to us, this is high level, ladies, and she’s clapping after every word. Don’t clap call clap the administration clap a car wreck clap. It’s not a car wreck. It’s an opportunity for collision shop owners who were badly hurt by eight years of Obama policies. Murdered even. She is telling us to leak that President Obama murdered collision shop owners.”

“Do you want me to call 9–1–1?” Cindy asked. “My boss likes me to put a resolution down before I close out the work order. I can write that you didn’t have an IT problem, per se, but that I called 9–1–1 for you?”

“No, it’s fine. This happened yesterday and it will happen again tomorrow. Thank you.”

4:37pm

“I’ll get this one,” Robin said as her phone rang.

“Hi, Merrick. Welcome back!” Robin said loud enough for everyone else to hear. “We missed you!” Robin cupped the receiver and then put Merrick Garland on speakerphone. “He’s back at the DC Circuit. Judge Garland, you’re on speakerphone just so you know.”

“Thank you for your service,” Art said, both to thank Merrick Garland for his service and also to pander to his co-workers who all seemed to love Merrick Garland.

“Judge Garland, you’ve probably noticed we updated your operating system while you were nominated to the Supreme Court,” Robin said.

“I did notice and I appreciate that very much. I can’t find a document, that’s why I’m calling. I think I had it saved to my desktop, which, I know, I know, it’s bad practice. We should save to a networked drive. It was the last thing I was working on before President Obama called me, and I lost my head for a minute.”

“Judge Garland, this is Gary. I saved everything on your desktop to your Dropbox.”

“Perfect!”

“Judge Garland, I’m so sorry,” Gary said sheepishly. “Your Dropbox password expired so I reset it to SupremeCourt17. It was back when,” Gary pantomimed a gun to his head, “Well, you know. Next time you log in, change it.”

“Gary, that’s fine. Please don’t worry. It’s not your fault. Who could’ve predicted any of this?”

“Not ‘House of Cards,’ that’s for sure.” Gary winked to Robin, who jotted down, watch ‘House of Cards’ onto her notepad.

Make America A Great Novel Again

There’s a Pulitizer Up For Grabs But You May Have to Go to Gitmo to Get It

And other answers to unsolicited questions

“I believe I am the one who can adequately chronicle these ridiculous times effectively! What’s your best advice to writing the Great American Trump Era Novel?” — Novelist Nat

If traditional media is the enemy of the American People, where do artists reside on the spectrum? Surely there is a sculptor out there doing work that would decimate the current administration. Would anyone see that decimating work? Possibly. If they ran out of gas next to a museum and were forced to wait inside while some staff searched for a can of gasoline. If the naked Trump statues of 2016 proved anything, it’s that there’s definitely a market for anti-Trump art. A free market, where one can wildly photograph it. But when protest art is as ubiquitous as Economist magazine covers, what could possibly be more shocking than presenting the current administration as it is? A weird mess.

There were no great 9/11 fictions. There were books that used 9/11 as a backdrop or plot device ham-handedly. The American novel is not particularly ascendant. When asked for the greatest American novelist of the last 50 years, people generally respond with Philip Roth. This is a shockingly bad answer. Portnoy’s Complaint is great. Goodbye, Columbus is pretty good. How many books can one guy write about a teacher sleeping with his students? About 20 is the answer. There’s nothing all that interesting about sleeping with students! Sure, they’re young and sexy. But they don’t know how to fuck! They also won’t get your ‘Gilligan’s Island’ jokes.

What does the American novel need to thrive? Possibly a villainous adversary in the White House. I was a great fan of all those Czech novels written behind the Iron Curtain. Kundera, Klima, Hrabal. Maybe American writers need to be oppressed to write transcendently. As poets, we’re always acting oppressed. No one pays attention to poetry. No one makes movies about poetry. But novels do have a rather well-worn path into the world, even if they never really get read. They will sit on your coffee table. Someone will ask “Are you reading that?” You’ll answer “Oh, yeah, I’ve started to. Mmm hmm. It’s supposed to be good.” Later it will be replaced on your coffee table by flowers. Or a different book. Or cheez-its.

The novels that have broken into cultural consciousness are the ones they make HBO shows and some movies about. Dystopian versions of the possible future like Hunger Games and dystopian visions of the past like Game of Thrones. Also the current fad of unreliable lady narrators in Gone Girl and The Girl on the Train.

Can you write an unreliable lady narrator dystopian book about the Trump Era? Sure. Hurry up. It might be over by the time you get it finished. Don’t adapt something you’re already writing to be the Great Trump Novel of 2017. Start over. Entirely. A novel from the point of view of Kellyanne Conway might be interesting. She is an unreliable lady narrator. But it seems like she’s already on the wane. Ivanka Trump! Now a novel from her point of view might be pure gold. Part-Lolita, part-Confederacy of Dunces. OK, so we have a main character. Is she unreliable? I’m pretty sure she only smiles in public. It’s a nice smile, but she probably saves it up for Canadian Presidents. And everyone else gets the fish eye.

Ivanka’s in on all the important meetings. In the corner probably scheming to gain the Oval Office for herself someday. She loves her dad but also knows that he’s nuts and a lech. She’s his main confidant and conscience. And from her point of view she probably is freaked out by all these lunatics that have latched onto his star.

I think the novels of today must reflect the technology of today. Filled with snaps and texts and emojis. I don’t know how to include snaps in your novel, ask your agent or editor. They probably know how to do that. I am only saying novels should have that. It’s ridiculous when novels don’t. People go to great lengths that unbelievable not to include stuff that everybody uses every day to do practically everything. And I’m not talking about cutting and pasting everything you’ve ever typed into Slack. But somehow use this technology everyone uses in some way.

Then, start deciding who should play your thinly veiled Ivanka Trump figure in the movie version. No one reads books, movies and TV are the only thing that truly matter. Jennifer Lawrence. OK, that didn’t take long and she’s perfect.

You want to make sure you make it into something that can be trilogy or a series of trilogies. The first 100 days could be the first book. Just a hair over 200 pages. And you can cut out the boring parts like signing Presidential decrees or whatever. Maybe there is an alien invasion. Of the White House. And since the place is in such disarray it’s Jared and Ivanka who figure out how to defeat the aliens. Don’t let the truth get in the way of a good story. No one in the Trump Administration ever does.

Jim Behrle lives in Jersey City, NJ and works at a bookstore.

Words Mean Anything Don't Anymore

Thought you was Sarah Palin bad? You no have idea.

Here some are statements from highlights of the few past weeks. These actual are things that are known to been have said by government official representatives.

I am very proud now that we have a museum on the National Mall where people can learn about Reverend King, so many other things. Frederick Douglass is an example of somebody who’s done an amazing job and is being recognized more and more, I notice — Harriet Tubman, Rosa Parks, and millions more black Americans who made America what it is today. Big impact.

I am proud to honor this heritage, and we’ll be honoring it more and more.

—Trump’s Black History Month remarks, Feb. 1, 2017

Well, I think there’s contributi—uh, I think he wants to highlight the contributions that he has made, and I think through a lot of the actions and—and, and statements that he’s gonna make, I think the contributions of Frederick Douglass will become more and more.

—Sean Spicer, Feb. 1, 2017 to the White House Press Pool in response to a request for clarification on Trump’s Frederick Douglass comments.

We have seen — and, by the way, General, as you know, James “Mad Dog” — I shouldn’t say it in this room — Mattis. Now, there’s a reason they call him “Mad Dog Mattis” — he never lost a battle. Always wins them and always wins them fast. He’s our new Secretary of Defense who will be working with Rex. He’s right now in South Korea, going to Japan, going to some other spots. And I’ll tell you what, I’ve gotten to know him really well. He’s the real deal. We have somebody who’s the real deal working for us, and that’s what we need. So, you watch. You just watch. (Applause.) Things will be different.

—National Prayer Breakfast, Feb. 2, 2017

One by one, the factories shuttered and left our shores, with not even a thought about the millions and millions of American workers that were left behind. The wealth of our middle class has been ripped from their homes and then redistributed all across the world.

—Inauguration Day Speech, Jan. 20, 2017

I’m making this presentation directly to the American people, with the media present, which is an honor to have you. This morning, because many of our nation’s reporters and folks will not tell you the truth, and will not treat the wonderful people of our country with the respect that they deserve. And I hope going forward we can be a little bit — a little bit different, and maybe get along a little bit better, if that’s possible. Maybe it’s not, and that’s OK, too…

We’re issuing a new executive action next week that will comprehensively protect our country. So we’ll be going along the one path and hopefully winning that, at the same time we will be issuing a new and very comprehensive order to protect our people. That will be done sometime next week, toward the beginning or middle at the latest part. We have also taken steps to begin construction of the Keystone Pipeline and Dakota Access Pipelines. Thousands and thousands of jobs, and put new buy American measures in place to require American steel for American pipelines…

You know what uranium is, right? This thing called nuclear weapons like lots of things are done with uranium including some bad things…

I — I think you would do much better by being different. But you just take a look. Take a look at some of your shows in the morning and the evening. If a guest comes out and says something positive about me, it’s — it’s brutal.

Now, they’ll take this news conference — I’m actually having a very good time, OK? But they’ll take this news conference — don’t forget, that’s the way I won. Remember, I used to give you a news conference every time I made a speech, which was like every day. OK?

— PRESIDENT DONALD TRUMP HOLDS A NEWS CONFERENCE TO ANNOUNCE HIS NEW NOMINEE FOR SECRETARY OF LABOR, FEBRUARY 16, 2017 [01:16:56]

Yesterday the president set — had an incredibly productive set of meetings and discussions with Prime Minster Joe Trudeau of Canada, focusing on our shared commitment to close co-operation in addressing both the challenges facing our two countries and the problems throughout the world.

No, there is — I can’t say it clearly enough. There was nothing in what General Flynn did, in terms of conducting himself, that was an issue. What it came down to, plain and simple, was him misleading the Vice President and others, and not having a firm grasp on his recollection of that. That’s it.

— Sean Spicer’s Valentine’s Day press conference, Feb. 14, 2017

Michael Flynn, General Flynn is a wonderful man. I think he’s been treated very, very unfairly by the media — as I call it, the fake media, in many cases. And I think it’s really a sad thing that he was treated so badly. I think, in addition to that, from intelligence — papers are being leaked, things are being leaked. It’s criminal actions, criminal act, and it’s been going on for a long time — before me. But now it’s really going on, and people are trying to cover up for a terrible loss that the Democrats had under Hillary Clinton.

I think it’s very, very unfair what’s happened to General Flynn, the way he was treated, and the documents and papers that were illegally — I stress that — illegally leaked. Very, very unfair…

So I’m looking at two-state and one-state, and I like the one that both parties like. (Laughter.) I’m very happy with the one that both parties like. I can live with either one.

I thought for a while the two-state looked like it may be the easier of the two. But honestly, if Bibi and if the Palestinians — if Israel and the Palestinians are happy, I’m happy with the one they like the best.

As far as the embassy moving to Jerusalem, I’d love to see that happen. We’re looking at it very, very strongly. We’re looking at it with great care — great care, believe me. And we’ll see what happens. Okay?

—Joint press conference with Trump and Netanyahu, Feb. 15, 2017

You look at what’s happening. We’ve got to keep our country safe. You look at what’s happening in Germany, you look at what’s happening last night in Sweden. Sweden, who would believe this. Sweden. They took in large numbers. They’re having problems like they never thought possible. You look at what’s happening in Brussels. You look at what’s happening all over the world. Take a look at Nice. Take a look at Paris. We’ve allowed thousands and thousands of people into our country and there was no way to vet those people. There was no documentation. There was no nothing. So we’re going to keep our country safe.

—Trump post-election campaign rally, Melbourne, Florida, Feb. 18, 2017

DAVID MUIR: Let me just ask you, you did win. You’re the president. You’re sitting …

PRESIDENT TRUMP: That’s true.

DAVID MUIR: … across from me right now.

PRESIDENT TRUMP: That’s true.

DAVID MUIR: Do you think that your words matter more now?

PRESIDENT TRUMP: Yes, very much.

DAVID MUIR: Do you think that that talking about millions of illegal votes is dangerous to this country without presenting the evidence?

PRESIDENT TRUMP: No, not at all.

— First interview as sitting President, with ABC’s David Muir.

See also:

Trump’s grammar in speeches ‘just below 6th grade level,’ study finds

The Cold

The Adventures of Liana Finck

Liana Finck’s work appears in The New Yorker and Catapult, and in her Instagram feed. Her first book, A Bintel Brief, was published by Ecco Press in 2014.

Bing & Ruth, "The How of it Sped"

“Welcome” “back.”

If, for the fifth week running — even after a break, even after amazing weather that briefly let you believe everything might be okay —you woke up this morning thinking, “Gah, we are really still doing this, huh?” I want you to know that you are not alone. You are in the majority. That will not keep the terrible things from happening, but at least it’s not just you. Does that help? Sorry, I’m not happy about it either.

Here’s something very pretty from the new Bing & Ruth record. That’s what I’ve got. Good luck out there today. Enjoy.

New York City, February 19, 2017

★★ Sunrise took the little clouds from purple into pink. For a while they had whitened to a metallic sheen, but then they lost their shine and their shape with it. The warmth was disproportionate and totally unjustified; it was not enough for t-shirts alone but people went with it anyway. The worker putting trash bags in the sidewalk cans sang loudly and hailed passersby. Boulders of snow stood separately from one another on the unpeopled green of the Sheep Meadow, the ruins or remains of snowmen. Saddle horses stood immense and placid unto motionlessness, awaiting riders. A shirtless runner overtook and passed a bicyclist in a parka with a fur-rimmed hood.

New York City, February 16, 2017

★★★★ The outdoors was bright, cold, and windy in a thoroughly appopriate way. Chalky spots of slush crust stuck to even otherwise gleaming paint jobs on passing vehicles. The wind rattled drily in the trash bags and sent pain creeping into bare hands, but it was not enough to cut short a walk. As the streets began to darken, pink shone on facades in the middle distance and a little loose pink cloud drifted above the street. Venus was clear and bright, though not as bright as the rooftop light bulb that had looked for a moment like Venus.

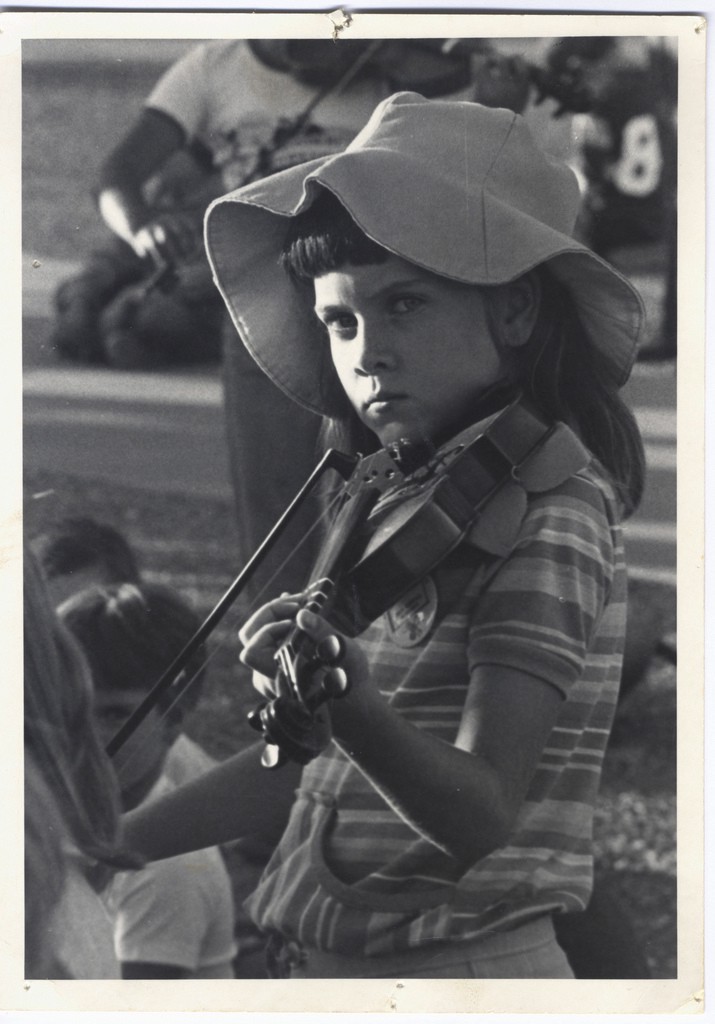

What Was the Suzuki Violin Method?

Teaching tiny people to play music.

In a house at the edge of a long and narrow river, I am crying. I am three years old, anxious to play the first notes on the tiniest of violins available, as a woman in a long dress instructs me to lift the instrument from the space beneath my elbow, hold it tightly between my neck and chin, and gently cross the strings with my bow. I know the violin; long before I am ever allowed to hold the instrument, I watch as men in tuxedos shimmer under lights at the symphony, as women in the lobby kneel with the smallest of passersby, allowing young children to closely inspect their instruments as they describe the make and function of each body’s parts. More than anything, I want to stand before an audience, to strike each sound with its own careful resonance and put forth the sum total of a cumulative tradition of presence. Through pursed lips, I steady my wrist, ease the reeded shape through my shaky grip as the teacher pauses, carefully adjusting my frozen posture as I try through both sweaty palms and stilted frustration and to begin.

In the years to come, I — like the half-million pupils each year that start with the Suzuki method — would grow into a small and adept violinist, a competitive student in a system that has churned out more accomplished players than perhaps any single method in history. Renowned musicians like Hilary Hahn, Rachel Barton, Jessica Guideri, Jennifer Koh, and David Perry each began with the program (“Among Pros, More Go Suzuki,” the New York Times suggested in 1982), and the method has grown to dominate the global conversation on musical pedagogy and youth education. Taking on students as young as three and four years old and squashing what once required years of study into a strict, incremental approach in ten books of sheet music, the Suzuki Method has largely subsumed all others as a sort of default method of violin instruction, one that now extends to numerous other instruments like viola, cello, piano, flute, organ, and even voice in renowned institutions across the world. Conferences like the Suzuki Association of the Americas meet annually with lectures and presentations and the system has its own strange and sprawling digital presence in forums and blogs, Facebook groups, Instagram tags, and YouTube channels, a surprising number of which are dedicated to video evidence of students completing the entire program by the age of six.

The method takes students through a ten sequential books, beginning with a few variations on “Twinkle Twinkle Little Star” and following through famously complex works from Mozart, Bach, Corelli, and others. The pieces largely come from the sort of standard Baroque repertoire that would be taught formally throughout the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, updated with a mix of children’s folk songs from Germany, France, and Hungary. Though completing the program doesn’t necessarily mean mastery, students who have the commitment to make it through the grueling 89 pieces (granted, some are movements in larger concertos and sonatas) tend to go on to play with high school orchestras, audition with conservatory programs, and make their way into the meticulous circuit of metropolitan symphonies in cities around the globe. Though most students either fall out before finishing or matriculate into public school programs rather than continue with the ear-oriented formalism, the full Suzuki program itself tends to take about ten or so years to complete, though this can vary widely under certain circumstances.

In the late 1940s, Dr. Shinichi Suzuki developed the method while working in his father’s violin factory in Nagoya, Japan. Despite being raised by violin makers, neither he nor any of his siblings ever had any aspirations to become musicians until one day in 1915, when a seventeen-year-old Shinchi allegedly heard a recording of Schubert’s Ave Maria. Inspired to devise his own self-education process, Shinichi spent the next few years listening to the recording over and over, slowly working out the mechanics of the song and instrument. Six years later, Shinichi moved to Berlin to study under the mentorship of German professor Karl Klingler, married German concert soprano Waltraud Prange, and returned to Japan to begin teaching his experimental ear-training technique to young students throughout the Tokyo area.

Much of the program’s proto-viral success lies in its track record for dazzling parents and educators alike with incredible outcomes from students of all ages. In 1936, Shinichi’s first student, the three-year-old Koji Toyoda, quickly delighted Tokyo newspapers after only four years of study, going on to win numerous awards in competitions, and eventually serving as concertmaster of the Berlin Radio-Philharmonic Orchestra. Others like Kenji Kobayashi would perform with world-renowned orchestras, earn coveted academic positions, and go on to start their own studios with the program, helping to expand the mentor’s message beyond the small island country of Japan to radically alter the course of music education globally. In 1958, students at Oberlin College would present a short film in which hundreds of Suzuki students performed Bach’s Concerto for Two Violins, inspiring academics like John D. Kendall to bring the method to the States himself, where over 350,000 children and adults alike still continue their education in the style to this day.

Through exposure to tonal exercises and early ear-training, the core of the program is built on the idea that nurture, not nature, has the most prominent impact on a child’s potential success in the arts. In his proleptic autobiography, Nurtured by Love, Shinichi notes that the “wrong education and upbringing produces ugly personalities, whereas a fine upbringing and good education will bring forth superior sense and feeling…all children adapt the vital forces of their organism to their respective environments.” Developed in Tokyo the 1930s, a time when music education was largely split between upper-class finishing schools and a handful of competitive conservatories largely confined to the West, Suzuki’s radical assertion that all could be musical — something that wouldn’t become fashionable in musicology circles until John Blacking’s How Musical is Man nearly three decades later — struck a chord with the global public, selling a methodic meritocracy where talent was built, not bred. Unlike most educational forms of the early-mid twentieth century that proposed the rigorous study of counterpoint, sight reading, and harmonic theory alongside performance, the Suzuki Method instead required all songs to be performed from memory, noting that, like language, children “add [each song] to their vocabulary or repertoire, gradually using it in new and more sophisticated ways.”

The parallels with language run deep. Music, like language, can be broken and into phoneme-like minutiae, taught as an accumulation of mechanical gestures, and applied to more and more complex pieces as a child’s talent grows. Elsewhere in Nurtured by Love, Suzuki writes of a certain biological aptitude that, like language, children have for musical instruction. Like Noam Chomsky’s famous assertion that a certain “Language Acquisition Device” allows children to grasp the complex constraints of even the most difficult languages in ways no longer accessible later in life, Suzuki finds that young students have a natural proficiency for aural acquisition, an assertion that later boarders on a sort of pseudo-scientific TED Talk bio-essentialism not limited to the musical parallels between certain Japanese nightingales and Osaka dialect. At one point, Suzuki invokes a certain 1941 lab test between Denver and Yale universities on children allegedly raised by wolves, who, after being socialized by the animals from birth, began to grasp objects with their mouths instead of hands, took water and food not limited to raw meats and vegetable “in a dog-like manner” and even had “head, breasts, and shoulders thick with hair.”

While so much of this pop psychology feels certainly dated in hindsight, the success of the program can’t be disputed. Freeing music pedagogy from the glut of developmental theory — which, beneath all else, showed even more impressive results with Suzuki — felt like an important victory for alternative education, and the number of independent teachers committed to the method would balloon into the tens of thousand throughout the 70s and 80s. Where most methods preached of righteous self-discipline, Suzuki’s focus on empathy and socialization through childhood development was one that made classical music — long out of fashion with North American students, especially in the late 90s when I began — approachable in a way that no other method would quite realize, at least not under the same constraints. Its encouragements of playful experimentation and agency gave the violin new life, so much so that the Times once, in reference Max Weber’s Rational and Sociological Foundations of Music, suggested it to soon displace the piano as the “consummation” of a new “bourgeois music culture,” a new, inexpensive default for youth musical education across the world.

The method isn’t without detractors; the program has long been the source of ire from competing methods, none as effective at ‘hacking’ the old institutional systems and streamlining youth education into the sort of blunt metrics and visible milestones that the American public education system loves, quite like Suzuki. Most recently, composer, author, and teacher Mark O’Connor turned heads when, in 2014, he boldly accused Shinichi of fictionalizing entire sections of his biography in promotion of the method. Where Nurtured by Love boasts of Suzuki’s achievements under the mentorship of German professor Karl Klingler, O’Connor revealed in a series of blog posts that Suzuki in fact had only auditioned to study under the professor, and was never accepted to study at the Berlin Hochshule where Klingler taught. O’Connor goes on to out Suzuki as never earning a PhD, never being endorsed by renowned cellist Pablo Casals, and never “mentored and watched after” by Albert Einstein, as are purported by his writing. Academics like John D. Kendall would go on to repeat these same inconsistencies, printed and reprinted by the press until firmly detached from realities, woven into a spotless narrative that bolstered both men’s reputations. “Of course Kendall had a huge stake in the potential Suzuki empire — he ran the SAA (Suzuki Association of the Americas) as its president for 30 years beginning in 1971,” O’Connor writes. “Was it all just about money, selling an exotic product from Japan to unsuspecting American violin kids?”

Counter-allegations, namely from the SAA themselves, would suggest that the stunt was done in promotion of the O’Connor Method, his own school with emphasis on the folk traditions of North America, but with a such staggering amount of archival research substantiating his findings, much of O’Connor’s outrage feels warranted. Whether or not a PhD is necessary to develop experiential education methods, much of Suzuki’s success in America was still bolstered by evidence of his institutional acceptance under a former Berlin Philharmonic concertmaster and without that, it’s both bizarre and, well, kind of impressive that the system ever got off the ground to begin with, almost purely on the electric success of the method’s world-of-mouth travel.

And so almost three years after this discovery, what, if anything, has changed? The Suzuki method is still overwhelmingly the dominant school across North America, and no other method has come to close delivering results with the same Earth-shattering impression glamor that the program once held, and perhaps never will. Even with a dubious background and an autobiographical manifesto bolstered by strange pseudoscience, what Suzuki brought to youth education has made the violin now more approachable than even the most seasoned competitors, allowing children, especially in low-income communities, to start on a path toward success in the arts. For all its faults, the fact that one particularly charismatic man from Japan — one who never attended college, barely studied at the professional level, and, especially in videos, seems barely able to perform some of the pieces himself — could radically alter the course of youth education feels like a wild and historically unprecedented development in a vastly conservative field of study. With his death in 1998, Shinichi Suzuki left a warm, humanistic impact on a procedural pursuit almost never associated with such, and even as his methods have been largely debunked as having more to do with rigorous practice than he’d ever admit publicly, the Suzuki legacy lives on in testament to his vision.