Hobbit Island Inexplicably Distressed By Nasty Foodstuff Shortage

There is some truly tragic news out of Decaffeinated Australia: “An announcement by New Zealand’s leading manufacturer of the black sandwich spread, Marmite, has sparked ‘marmageddon’ fears among Kiwis. Food company Sanitarium said on its website that supplies “are starting to run out nationwide” after ‘our Christchurch factory was closed due to earthquake damage’. Even Prime Minister John Key said he is rationing his personal supply.” EVEN THE PRIME MINISTER WILL NOT BE SPARED. I don’t know what the people of New Zealand are going to do, except probably eat something less foul and vile.

How To Make Hard Apple Cider

How To Make Hard Apple Cider

by Willy Blackmore

I woke up hungover the other Saturday. It was just a mild headache, a low-level pain easily vanquished with a cup of coffee and a few glasses of water. But the hangover was special to me all the same, because I’d made it myself. The night before, a few months after buying five gallons of unpasteurized apple cider from an orchard east of Los Angeles, I got drunk for the first time off of my homemade booze.

This is how you make hard apple cider: simply put, do nothing. Apples are sweet, and their skins are covered with wild yeasts, giving you the only two ingredients needed to make alcohol. Yeast devours sugar and booze is born.

There are eight billion things that can be added to cider, and if you were to fall into the black hole that is the world of home brewers’ message boards (Exhibit A), you can read the various reasoning for adding sugar, honey, ascorbic acid, sulfites, yeast, heroin, nutrients, enzymes, and various other narcotic-looking powders. But when I cook a fucking steak, I season it with salt, and true to minimalist form, I added nothing to my cider. The juice was dumped into a plastic bucket I bought at the homebrew store and largely left to its own devices.

Booze made with one ingredient and no work may sound like the perfect recipe for broke, lazy drunks — and it is! — as long as you have patience. And there’s a bit of work to do along the way, like siphoning the nascent alcohol from one container to another every month or so, leaving behind the film of dead yeast and sediment that sinks to the bottom.

There’s also the rotten-egg state to be reckoned with, when sulfurous gas starts to leak out of the sealed fermenter, filling, say, the kitchen with the stench of rotting bodies. On those messages boards, homebrewers call these “rhino farts,” a name that’s really too kind.

One more deterrent for lazy boozehounds thinking about getting all DIY: bubbles. Apple juice left to ferment for a few months will turn into something undeniably boozy, but it’ll be flat too. If the four or so percentage points of alcohol my cider weighs in at were easy to come by, carbonating it was far more difficult. It’s not that there’s a lack of bubbles involved in making booze — my cider was kicking off so much C02 that I practically knocked myself out cold after inhaling a cloud of it. It’s capturing that gas that’s the difficult part — the part that involves math, science-y measuring devices and the anxiety born of knowing that the two cases of 750 ml bottles full of cider sitting in your girlfriend’s closet could turn into so much apple-y shrapnel if things go wrong.

Here’s the gist of it: seal slightly sweet cider in a glass bottle, leave it the hell alone, and you’ll have a drink with some fizz to it in a few weeks. But if the cider is too sweet, if the bottles get too warm, if the glass isn’t strong enough… boom. The ten-foot arc of cider I sent spraying across a friend’s apartment when opening one bottle is as close to an explosion as I ever hope to come.

But catching a homemade buzz is an end that justifies the means only if the cider actually tasted good. And so: it smells a bit funky — like a horse, as one friend put it — and like yeast, too; the taste: tart and apple-y. It has none of the earthy, almost meaty depth of French ciders, or the intense tartness of Spanish ones. But it’s drinkable, which is all I was hoping for, and it was agreeable too.

The cider wasn’t the only batch of alcohol bubbling away in my apartment. There was a small lot of wine made from Grenache grapes grown near Ojai, too. And now every time I open a bottle of cider, I have to sacrifice a small, sparkling sip, one poured out in memory of its 2011-vintage brother, because that wine was an unmitigated disaster. Making wine was part of a larger project for me, one in which I grow up to be an old Italian man. So my attempt at winemaking followed my imagined school of old-man basement winemakers of the East Coast and Italy, one in which you just stomp on the grapes and don’t do — or add — much of anything else. My winemaking experiment cost a few hundred dollars — sixty pounds of grapes, a five-gallon fermenter and some other booze-making supplies. But that money largely went to waste, as I proved to be a grand failure of a vintner.

Pine Sol. Dry-erase markers. Burnt rubber. Tires. Eraser. These are just some of the lovely scents that wine had to offer. Having smelled and tasted the Grenache from its alcohol-free youth, before the various bacterial infections and attacks by ethyl acetylene turned it into something far worse than sour grapes, I know that there was something appealing about the juice — something the proceeding months completely obliterated. I’m afraid to even let it turn in to two gallons of vinegar.

If I try my hand at making wine again this fall, my approach will be less laissez-faire. But I won’t change the way I ferment my second vintage of cider — I’ll just make more of it. Those two cases of 750ml bottles are a stockpile that will be killed off after a month or so worth of spring picnics.

With this second round of cider I might be more ambitious in sourcing and pressing the juice, too. I’ve heard tell of an old, gnarled orchard of heirloom apples not far from L.A., and to buy part of the crop and pulp and press the apples myself would be ideal. But to do so would involve retrofitting the motor and blade of a garbage disposal to pulverize the apples and buying or building a basket press to extract the juice — far more work at a far higher cost than simply buying some juice and more or less ignoring it. I wouldn’t want to lose sight of the end-goal of making booze at home, namely, actually getting drunk off your own supply.

Willy Blackmore is the Los Angeles editor for Tasting Table. He has a Tumblr.

City Potholes To Be Filled With Aquaphalt Water Curable Cold Patch

“Keeping our streets in good condition is essential to our economy and to our quality of life — and that’s why we are always looking for ways to do the job more efficiently. We’re debuting new technology to repair city streets faster, while closing less lanes to traffic. We also took advantage of the mild winter this year and resurfaced additional key corridors to get a jump on repaving season, and we are on track to repave 1,000 lane miles of city streets this year.”

— Mayor Bloomberg held a press conference in Queens today to brag about the city’s new pothole-filling technology. Last year, the Department of Transportation set an all-time record by filling an astounding 418,000 potholes. And with the mild winter allowing more pothole-filling than ever, they’re already 164,000 filled potholes towards challenging that record this year. Also, there is something called, “Aquaphalt Water Curable Cold Patch.”

How To Not Drink

Here is a 12-step plan for getting sober, should you be inclined to so do. For those of you who would be more interested in a 12-step plan for simply cutting down on the number of drinks you have each night so that you can still get to sleep without tossing and turning but not wake up the next day a sweaty, quivering wreck whose condition is so delicate that the only unfortunate cure to alleviate the physical discomfort (not to mention the shame) is to have a drink on the early side, which inevitably becomes several drinks, which results in another day where by the time you finally pass out you’ve had so much alcohol that when you wake up in the morning you will be a sweaty, quivering wreck whose condition is so delicate that the only unfortunate cure to alleviate the physical discomfort (not to mention the shame) is to have a drink on the early side, which inevitably becomes several drinks, which results in another day where by the time you finally pass out you’ve had so much alcohol that when you wake up in the morning you will be a sweaty, quivering wreck whose condition is so delicate that the only unfortunate cure to alleviate the physical discomfort (not to mention the shame) is to have a drink on the early side, which inevitably becomes several drinks, which results in another day where by the time you finally pass out you’ve had so much alcohol that etc., well, I would be interested in a plan for that too, so if you hear of anything let me know.

Photo by Stéphane Bidouze, via Shutterstock

Would You Drink Panda Doody Tea?

On the one hand, the tea is very expensive and is made from panda doody. Also, there is no other hand.

Inside The Secret Networking Club For The Giant Monsters Who Rule Over Us All

“All talls quickly learn that all things cost more, so earning more money is a must. Car size cannot be too small. Airlines always charge more for the extra room. Clothing must be custom-made or -sewn.”

— It is so hard being a tall! Also, they call themselves “talls.”

Photo by Everett Collection, via Shutterstock

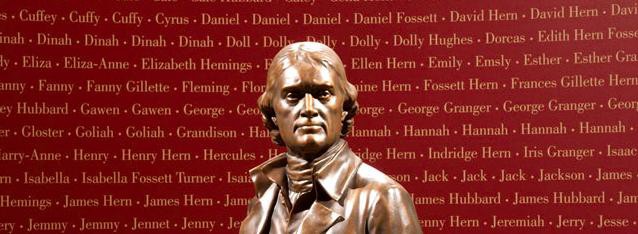

The New And Improved Thomas Jefferson, Enlightened Slave Owner

The New And Improved Thomas Jefferson, Enlightened Slave Owner

by Leah Caldwell

When the Smithsonian exhibit “Slavery at Jefferson’s Monticello: Paradox of Liberty” opened this past January it was greeted with a great deal of praise. A review in The New York Times called the exhibit “subtle and illuminating.” The Washington Post described it as “groundbreaking.” The hype surrounding the exhibit was understandable. This opening marked the first time that a museum on the National Mall has prominently acknowledged the fact that Thomas Jefferson owned 600 people in his lifetime.

The exhibit will be open through October, and on a recent weekend visit, it presented a picturesque scene of civic engagement, the horseshoe-shaped hall crowded with visitors, most of whom appeared to be from out of town. The crowd shuffled along slowly. Not far in, a young girl, white, about seven years old, paused in front of me and read a placard situated at child’s eye-level: If you were enslaved, would you run away? Two elevated panels next to the question presented her with the options “Yes” or “No,” in the style of a choose-your-own-adventure. She flipped up the “Yes” panel and the words seemed to snap back at her, complicating her choice: “What about your friends and family that you’d never see again?” She lifted the “No” panel, which revealed a terse, open-ended “Why not?”

Her dad remarked, “Pretty tough choice, huh?”

About 20 minutes later, I saw an older black woman, maybe 60 or so, drag her companion over to the same placard, asking him if he had seen this yet. They scanned the display and laughed; she said something to him under her breath, and they moved on.

“Would you run away?” was not the only question posed by the exhibit. Further on, another placard asked: If you were a black person with very light skin and could pass for being white, would you? Answer “No” and you’re presented with the following: “What are the benefits to being a person of color?” The hypotheticals had veered into territory reminiscent of educational Underground Railroad video games, but with the central characters now being Jefferson’s slaves.

Just a single line — set in a 24-point-sized font that you might easily miss if you weren’t looking — acknowledges that it’s “likely” that Jefferson fathered four of Sally Hemings’ children.

The names of these slaves are displayed prominently along a wall, painted a deep red, that curves around a statue of Jefferson when he was young. At least 600 people were enslaved at Monticello during Jefferson’s life, and for this exhibit, researchers have painstakingly pieced together some of their family trees and personal histories in an effort to reconstruct what their lives were like, at Monticello and after.

One of the displays near the back of the exhibit is dedicated to the Hemings family. This history was perhaps read more closely by most, although if you didn’t know anything about American history you might be confused as to why. Just a single line — set in a 24-point-sized font that you might easily miss if you weren’t looking — acknowledges that it’s “likely” that Jefferson fathered four of Sally Hemings’ children.

Lonnie Bunch, who co-curated the exhibit, has said that scholars have known about Jefferson’s “relationship” with Hemings for a long time, but “the public is still trying to understand it.”

Here is what the public is trying to understand: When Sally was 14, and a slave at Monticello, she accompanied Jefferson’s daughter, Polly, on a trip to France in 1787. Jefferson was about three decades her senior and widowed. She lived in France for two years, returning alongside Jefferson after the French Revolution. Their “relationship” turned sexual either in France, when Hemings was about 16, or upon their return to Monticello. Sally herself was born not far from Monticello. She was Jefferson’s wife’s half-sister, having been born to John Wayles, Jefferson’s father-in-law, and Betty Hemings, who was enslaved on Wayles’ plantation.

Until at least 1998, many of Jefferson’s biographers rejected this narrative. As biographer Joseph Ellis said in his 1997 book American Sphinx, this type of affair would have “defied the dominant patterns of his personality.” But once DNA evidence confirmed that Jefferson had “likely” fathered several of Hemings’ children, the dissenting views became the province of groups like the Thomas Jefferson Heritage Society that vows to “stand always in opposition to those who would seek to undermine the integrity of Thomas Jefferson.” In 2000, the Thomas Jefferson Foundation, which runs Monticello, released a report stating that there was a “high probability” that Jefferson fathered six of Hemings’ children, even though the current exhibit puts the number at four.

If anything, it’s not that the public has had trouble “understanding” the affair, it’s that many scholars and public institutions have been blocking the view.

In other words, what the exhibit is disclosing in 24-point font is a fact that first appeared in print in the early 19th century. And yet what’s odd about “Slavery at Jefferson’s Monticello: Paradox of Liberty” is how quickly acknowledgement shifts into full embrace. With the exhibit, Jefferson is reborn into yet another incarnation, that of the Greatest Gentleman Slave Owner of the United States. Knowing that Jefferson owned slaves helps us gain a “more comprehensive understanding” of the man himself, says a Monticello curator. At the Smithsonian blog Around The Mall, a write-up of the exhibit explains that “understanding Jefferson’s own complexities illuminates the contradictions within the country he built.” In this way, slave-ownership is quickly reduced to an attribute of a deeply conflicted, complex Jefferson.

“Paradox of Liberty” is a partner exhibit between the Thomas Jefferson Foundation and the future National Museum of African American History and Culture, which opens in 2015. Bunch, the museum’s founding director, has said

that the “Paradox of Liberty” is just one of several feeler exhibits that will help the future museum gauge public reaction to such difficult subjects as slavery. In addition to his role as the museum’s director, Bunch is an author and respected academic. His 2010 collection of essays, Call the Lost Dream Back, includes an anecdote that recalls a childhood baseball game in the 1960s. A group of white kids turned against him, hitting him with a bat, and pursuing him on foot. Running away, Bunch thought, “this is what it must have been like for a runaway slave.”

A youth guide to the exhibit reads “O is for Overseer. To help manage his property, Jefferson hired overseers to supervise the laborers and work being done.”

However laudable the goals of “Paradox of Liberty,” it doesn’t bode well that if you entered the Jefferson exhibit not knowing what slavery was, you might come out thinking it was an intensive training program for highly-skilled craftsmen. Each of the families discussed is given an association with a specific trade, like nailery or joinery, but mentions of overseers and brutality are scarce. One mention of a rough overseer is equivocated by mentioning, in the same placard, that Jefferson was against harsh treatment of slaves. A youth guide to the exhibit reads “O is for Overseer. To help manage his property, Jefferson hired overseers to supervise the laborers and work being done.”

The racial split of the crowd during the few hours I was there was maybe 70 percent white, 30 percent black. And at least some of the visitors, including some young enough to be relying on that youth guide, seemed to have a take on slavery that exceeded the exhibit’s content. “Whites were evil,” a white boy, about eight and wearing a Knicks jersey, said to his dad. “Yes, for a period of time, the whites were evil,” his dad responded. The boy and his siblings made their way to the giant model of Monticello. “Are these slavery camps?” the same boy asked. “It’s called a plantation,” the dad said. The boy immediately responded, “Isn’t that the same thing as a slavery camp?”

A few steps from the model, a glass case displayed Jefferson’s spectacles and a text by Herodotus, evidence of the claim that Jefferson was a man of the Enlightenment. It is only once visitors pass this gauntlet of Jefferson’s enlightened knickknacks do we reach the exhaustively researched stories and mapped-out lineages of the enslaved families of Monticello. A black man in his twenties, looking in the glass case with Jefferson’s spectacles, quipped sarcastically, “My question is: Just how enlightened was he? He was a slave owner.”

In his review for The New York Times, Edward Rothstein lauded the exhibit for its willingness to let the visitor make sense of the gap between Jefferson’s ownership of slaves and his “ideals.” But he was not all praise. About an exhibit placard which states Jefferson’s Declaration of Independence “did not extend ‘Life, Liberty, and the pursuit of Happiness’ to African-Americans, Native Americans, indentured servants, or women,” Rothstein said it “pushed too far.” This is “political boilerplate,” he said, continuing, “each of those cases needs different qualifications and examinations. They distract from the subject.”

Even though this exhibit is devoted to the stories and histories of the enslaved families of Monticello, Rothstein wrote that Jefferson’s achievements still must be seen “whole” and that “right now the exhibitions need a more deliberate elaboration of his ideas and life.” Rothstein explains that, yeah, Jefferson owned slaves, but we have to give credit where credit is due. “If slavery was, throughout global history, the rule, the exception was the last 200 years of gradual worldwide abolition. And Jefferson, for all his ‘deplorable entanglement,’ helped make it possible.”

After reading Rothstein’s critique, I found myself thinking of the National Great Blacks in Wax Museum in Baltimore. Built in 1983, the museum mostly hosts wax figures of prominent black politicians, astronauts, and revolutionaries, but visitors are more likely to remember two particular exhibits. One is the recreation of a slave ship at the entrance to the exhibition hall, where among other horrors, a model of a naked woman is chained to the ceiling with whip marks on her body. The next is the lynching exhibit in the basement. Newspaper clippings, poems, and song lyrics document the horrific and common tales of lynching in the US. Inside a glass case, papier-mâché-like figures remain fixed in the scene of a brutal lynching. A pregnant black woman has had her womb ripped open, her baby removed and replaced with a cat.

Back at the Smithsonian exhibit, there’s a display dedicated to the nailery at Monticello where enslaved men made nails. Children are encouraged to lift a 10-pound bucket of nails since a slave at Monticello, on average, would make 10 pounds of nails a day. “Can you imagine having to do that every day?” a father asked his daughter. She didn’t respond, but used her full body weight to lift the bucket about an inch from the ground.

On the way out the visitor is presented with another wall of names, a sign thanking the donors who have contributed at least one million dollars to the National Museum of African American History and Culture, a list that includes: Boeing, the Oprah Winfrey Foundation, Bank of America, Walmart and Target.

Leah Caldwell is a writer at Al-Akhbar English.

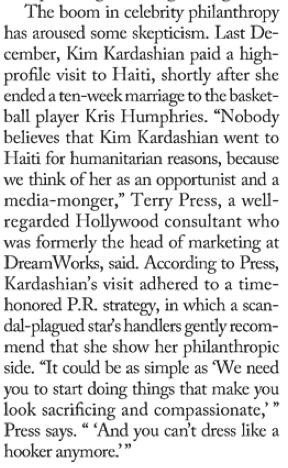

But You Already Knew How Public Relations Works

Today’s New Yorker story — which is subscription-only — will make you feel bad about both celebrity and philanthropy!

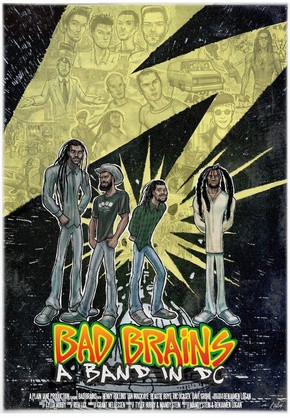

'Bad Brains: A Band In D.C.'

by Awl Sponsors

Tap into the best coverage of SXSW 2012, presented by MasterCard PayPass by visiting here. A sample:

Aside from the obvious — they were the first all-black punk band — two additional things must be said of the early Bad Brains: they were the most ferocious musical tornado ever unleashed; a frantic, thrashing monster of a group that had absolutely no competitors for the crown of being the most hardcore of all of the hardcore bands in Washington, D.C.

They were also the best, most skilled musicians of any of their compatriots. Sure, they played buzz-saw punk rock music that sounded like a Black Sabbath album spinning at 45rpm, but they actually came from a jazz fusion background (think Return to Forever and Mahavishnu Orchestra!) before the energy of the D.C. hardcore scene turned their attention to punk.

Lead vocalist H.R. was, simply put, one of the greatest frontmen of the punk era, up there with Johnny Rotten or Jello Biafra as a presence so incendiary, so crazed and so utterly unhinged that you wondered if he was possessed. Backed by Dr. Know (guitar), Darryl Jenifer (bass) and H.R.’s younger brother, Earl Hudson, on drums, the Bad Brains would explode onto the stage like a nail bomb had gone off. If that prospect seemed worrisome, well, stand back!

It wasn’t long before the group found they weren’t able to play shows in their hometown, hence their famous number, “Banned in D.C.” which has been appropriated for the title of the new film about the group, Bad Brains: A Band In D.C., co-directed by Mandy Stein and Ben Logan. The film actually started as an offshoot of another project about CBGBs but, as Stein told us, “What director wouldn’t want to tell this story?”

The 30+ years of the Bad Brains’ existence has been fraught with interpersonal conflict — one epic argument was caught on video by the directors — but it’s that tension that makes the band so great that also, perhaps, prevented them from being as big as they might have otherwise been. Band in DC features some fierce archival footage, more recent live performances and interviews with Henry Rollins, The Beastie Boys, Fugazi’s Ian MacKaye, British black punk DJ and filmmaker Don Letts and The Cars’ Ric Ocasek, who produced the band in the studio.

In the clip below, co-director Mandy Stein and Bad Brains singer H.R. discuss the film and the energy of the early Washington, D.C. punk scene.

“Bad Brains: A Band in DC” Interview at SXSW from Largetail on Vimeo.

Maria Thun, 1922-2012

“Planting the vegetables when the moon was in different constellations, she discovered, resulted in their growing into different forms and sizes. Over years of research she concluded that root crops (including onions and leeks, which are not technically root crops) do best if sown when the moon is passing through constellations associated with the earth element; leafy crops do best when the moon is associated with water signs; flowering plants do best associated with air signs, and fruits did better with fire signs.”

— German gardener Maria Thun, who put the “biodynamics” theory of cosmic, occultist philosopher Rudolph Steiner to test in her garden

and wrote a popular series of planting and sowing calendars based on the results, died last month at the age of 89. More recently, her ideas have been influencing the wine industry, as some people believe that wine tastes better when it is drunk on days that correspond to her calendar.