Man Still Typing

“I had to catch a train in Washington last week. The paved street in the traffic circle around Union Station was in such poor condition that I felt as though I was on a roller coaster. I traveled on the Amtrak Acela, our sorry excuse for a fast train, on which I had so many dropped calls on my cellphone that you’d have thought I was on a remote desert island, not traveling from Washington to New York City. When I got back to Union Station, the escalator in the parking garage was broken. Maybe you’ve gotten used to all this and have stopped noticing. I haven’t. Our country needs a renewal.”

— It’s like Tom Friedman lost a bet and had to write a parody of the stupidest Tom Friedman column anyone could imagine.

Is This the Internet's Most Magical Moment?

Sure! She is vegan. @KatyCatsNow “hi Nancy do you know who Fiona Apple is?

— Nancy Sinatra (@NancySinatra) April 18, 2012

This is totally apropos of nothing, but seeing this made me feel like the eggshell that cases my mind had finally cracked open, and I could no longer tell where I stopped and the magic of the universe began.

Today Only: The Awl Is Auditioning New Commenters!

Just a reminder to all denizens of the Internet that we are finally holding auditions for new commenters today. It’s been a long time since we had any open commenter slots, but with some recent turnover in the commenter market, today’s the day!

Interested? We’re looking to fill the following commenter positions; apply within!

1. Master or mistress of puns, in-jokes, memes and general nonsense. This commenter serves to set the tone for all other commenters, by running normal comments through a random word generator, as well as making jokes about Tumblrs with fewer than 200 followers and things seen on other sites that we don’t read. Commenter should also create an extensive series of semi-humorous callbacks to already-corrected errors of months ago on the site.

2. Slightly sycophantic drunk gay guy who has strong opinions about TV who turns exceedingly nasty after midnight. We lost our most recent one in a tragic house fire. (Drunk gay guys have a 30% chance of their house kimonos meeting their cigarettes during the course of their blog commenting.)

3. Social Mores Watchdog Commenter. This person provides leftist counterpoint, and decides when we’ve not been obviously ironic enough in mocking poor people, people with disabilities and New Jersey governors. Also Jews. Stridency a must! Note: This position can also be filled with The Angry Accessibility Expert, whose profanity-laced comments are concerned solely with issues affecting colorblindness in web design. Requirements: must be a hot piece of eye-candy.

4. Assistant or former assistant or person who was once interviewed for a position as an assistant or person who was a roommate once of someone who once interviewed to be an assistant to: Tina Brown, Graydon Carter, or Barry Diller. This is the all-important “nexus of speaking truth to power” commenter position. This person is deeply informed on the workings of Manhattan society due to their extremely short period of proximity to the corridors of influence. In the future, it’s likely that this commenter will be promoted to chief commenter (or possibly “only commenter”) when we redesign our comments system later this year.

5. The Shocked Prioritizer. Generally should only comment in the formulation “I can’t BELIEVE you’re wasting time talking about [x] when [y] is also happening.” Requirements: must have logged at least 40 hours reading Jezebel.

6. Disbarred lawyer. Provides long and just-slightly incorrect and hasty review of all blog posts regarding the law.

7. The London commenter. The London commenter has a small but important role to fill, correcting our posts about David Bowie videos of the 80s and early Belle and Sebastian B-sides, and generally opining about shoes. Must also email us weekly with Bandcamp and Soundcloud links to obscure and not very good new bands.

Pay: none. Benefits: none. Social rewards: none. Please submit your application as an extraordinarily large PDF attachment, with no cover note, from a fake Gmail address, to AJ@deadspin.com.

Our Culture Needs Better Monsters! An Interview with Brian McGreevy

by Desiree Browne

In an essay for New York’s Vulture blog last year, author Brian McGreevy argued that “over the last decade, something has gone terribly wrong with the modern vampire. Take the biggest offender, Twilight. Granted there is an inescapable genius to its command of 14-year-old girl psychology; its premise is that the hot, broken guy who breaks into your house to draw you while you sleep wants to wait until marriage until he nearly screws you to death on a feather bed.”

McGreevy’s new novel,

Hemlock Grove, published as part of the FSG Originals series, goes straight for the jugular, so to speak. Set in a Pittsburgh suburb, the novel centers on the grisly murders of teenage girls but the usual suspects, one werewolf and one vampire, are the least scary things stalking the sleepy little town. McGreevy lives in LA, where he’s also a screenwriter (right now he’s working on an adaptation of Dracula as well as one of his novel for Netflix). We talked by phone recently about what’s really scary, darkness and the best shaman in Park Slope.

Desiree Browne: How did Hemlock Grove get started?

Brian McGreevy: I was in graduate school at the time and there seemed to be a tendency to homogenize fiction. And I realized working in the mode of New Yorker-style writing — The New Yorker claims not to have a house style and it absolutely does — and I just realized I didn’t have an interest in that. That I wasn’t good at it, and that I should write about what I cared most about in the world, which tended toward blood and monstrosity. But at the same time I didn’t want that to be at the expense of psychological nuance and taking a certain amount of pleasure in prose as a medium.

This is stuff you were really into as a kid?

It’s stuff I’ve been into my entire life. I think everyone who’s being honest is into this kind of thing. In anthropology there’s a term they use called “the Jurassic Park syndrome.” It explains why monsters and predation are tropes that are extremely elemental to every storytelling tradition in every culture in history. The idea was that there was a huge amount of survival value to being intrigued by predators conceptually because it made you more likely to understand them. If you’re more likely to understand them, you were less likely to be killed by them — and then you could pass your genes along.

Did you believe that werewolves and vampires existed?

Fuck, I still do. I’m not exaggerating. If you look in the acknowledgments of the book, there’s one woman named Maja D’Aoust. She’s the self-described White Witch of Los Angeles. I can recommend a shaman in Park Slope. Her name is Mama Donna; her dog’s name is Princess Poppy. This is stuff that is not much of a stretch for me. I’ve had experiences where I had an ex-girlfriend that I knew was really mad at me and for no reason that the laws of physics could justify, a lamp would topple over in my room. I’ve had a sufficient number of occult experiences and synchronicities that to me it’s like love or orgasm. There are people who say, “yeah, people have orgasms” or “love doesn’t exist,” but once you experience it, it [love] actually does, and to me magic is more or less the same way. Once you’ve had an empirically indefensible thing happen to you, you now live in a world where that’s possible.

What’s your favorite Gothic novel?

It’s not the answer that most people would think. I would categorize One Hundred Years of Solitude as a Gothic novel. The Gothic novel has certain major tropes. For instance, an attraction to exploring extremes within the human condition manifesting light and darkness. In One Hundred Years of Solitude, you have profoundly evil characters doing profoundly evil things and then you have another character who’s literally so transcendental she ascends into the heavens. And then it culminates in an apocalypse. If that’s not Gothic, I don’t know what is.

Did you set out to change the vampire novel?

Not necessarily. I’m of the mind that you can’t really game the system, which is to say that you can’t calculate a creative project, per se. All you can really do is express the thing that is most exigent for you to express. There’s a metaphysics to syntax. So if you look at the phrase, “I was struck by lightning,” it’s like, yes, you were struck by lightning. It’s the reverse of “I had an a feeling.” What do you mean you had a feeling? You didn’t have a feeling, you didn’t decide to feel this way in this moment. Feelings happen to you the same way lightning happens to you. And really all you can do is to decide whether or not to go with it.

So no, I didn’t decide I was going to do something weird with the vampire novel. It was more, “here’s this weird-ass thing I want to do. It’s very compelling to me at the moment, it will be compelling to me for a number of years.” But then I started doing research and making creative executive decisions. One of those decisions was not to ever use the word “vampire” in the novel because I didn’t want the cultural freight of that word. I wanted to do something that was more mysterious and existed in a nebulous place where the light is coming from the darkness. In my research it was figuring out, “what’s the role for this? Oh, I’ve seen that a trillion times before and I don’t want to do that version of it.” It wasn’t me deciding “here’s what I’m gonna do,” it was retreating from what I found uninteresting.

Still, it’s obvious you did a lot of research and stuck to some conventions.

Well, the approach to research for this book was pretty funny because the first draft came out extremely, extremely quickly. I did a cursory amount of research going in and found out that there was this Slavic name for vampire, “upir,” so I used that instead of the word “vampire.” I learned about this concept of a vargulf, a werewolf that has gone insane and doesn’t eat what it’s killed. It wasn’t until after having written two or three drafts that I really went down the rabbit hole of research and just read dozens and dozens of books on various subjects that ended up informing the novel very significantly. But also, it was important to me at the time to not have this sense of purposefulness, in that the research I was doing was clarifying ideas I’d already had as opposed to introducing me to new ideas, if that makes sense. The biggest part of working on this book was figuring out how to articulate a series of preconscious ideas that the first two or three drafts consisted of.

What were some of those ideas?

Well, this concept of initiation, with both the two young male protagonists. The term “initiation” describes a ritual death and rebirth, which from the perspective of developmental psychology is this necessary rite of passage between the child self and the adult self. Both Peter and Roman in their perspective arcs of the book are going on to become the man they’re going to become. That’s something that’s of reasonably deep thematic interest to me because we live in what I would call a spiritually troubled time where, especially in coastal cities like New York or Los Angeles, it becomes difficult to identify when adolescence actually ends. I’ve lived in Los Angeles and met people who are middle aged who seem to be in an emotional state of adolescence.

There’s also such a dichotomy between religion and science. You’ll get dating profiles where they ask, “what are your religious beliefs?” and one of the categories is “spiritual, but not religious.” Are you fucking kidding me? They’re synonyms. That’s like saying, “I’m damp but not wet.” The empiricism of science is something that is very noble and reliable and in no way am I diminishing its significance, but there’s a place where its function ends. It’s the function of religion or spirituality or whatever the fuck you want to call it to answer the most significant questions that a strictly rationalist approach is not qualified to answer it. When people are on their deathbeds, they don’t ask to talk to a physicist.

But there’s not a lot of a religion in the book. Not in a very obvious way, at least.

Religion is something I certainly think about a great deal. My mother and father are both Presbyterian ministers. It comes back, to a certain point, to a definition of terms. When most people hear the term “religion,” their brains plug in the traditional. I have some interest in institutional religion from an anthropological perspective, otherwise I really don’t give a fuck. To me, the religious ideas that are in the book are much more primal and preagrarian, in a way. There’s natural balance to things, you exist in accordance with that balance and if you don’t you’re going to be punished. Not in some sort of Calvinistic way. You behave this way because it’s this natural flow of the universe and if you go against it, you’re going to suffer. Either in a manifest way or you’re just going to be so completely fucking unhappy there’s really no distinction.

Talk to me about your Vulture piece, which argued that “Don Draper is a far better vampire than any of Twilight’s or True Blood’s.” There were a lot of people that were really upset by the ideas you expressed there about what modern vampires should be. What in your view is fundamentally wrong with most of today’s vampires?

What the Vulture piece says I will essentially stand by. You don’t get to have your cake and eat it, too. When you have a female friend, and I have plenty of platonic female friends, they’ll date a guy and say, “Oh, yeah, there’s this guy I like. He’s great in every way but I’m not that interested in him.” Yeah, you’re not that interested in him because he’s being too nice to you and you know what his cards are. And then they’ll be dating this guy who’s kind of a piece of shit and they say, “He won’t text me back, he’s playing these games, he’s doing this he’s doing that and I’m really upset with him” and it’s like, are you fucking kidding? This guy is a bad idea. You’re completely oblivious to the virtues of the nice person and you’re completely obsessed with this guy who’s being a shitbag, and that tends to be pretty consistently true in my experience. So when you take this to a metaphorical level where in pop culture you say, “This guy is a bad idea on every level but actually it’s secretly because he loves you and it’s a really good idea and will commit to you”? That’s not how the fucking world works! This guy is a bad idea because he’s a bad idea. That was something that was very essential to me in committing to the adaptation of the novel [I’m doing for Netflix] with a character who’s very seductive. I didn’t want to morally whitewash him in anyway.

You really humanized the monsters for the most part in this book. We really get a chance to feel sympathy for them. Why was that important to you?

In depth psychology, which was very informative in the writing of the novel, there’s a term they use call “the uncanny effect.” It’s taking something that we don’t recognize in order to recognize ourselves more profoundly. And to me the premise of monstrosity is that it’s something that we find deeply empathetic and relatable, so what I had no interest in doing was creating a villain. And, at least from my own perspective, the novel doesn’t have a villain. There’s not a single character in that book that I personally can’t look at things from their perspective and think, “oh, well, yeah, I get where you’re coming from.”

Really?

Any one of them. This goes back to the idea of bourgeois sentimenality, which I have no real interest in advocating. People are very stuck in these proscribed ideas and values whereas the world is a lot fucking bigger than that and whether or not it’s something you endorse or that or how you choose to live your life, admit for a second that a lot of unpleasant things had to happen for you to live a pleasant life and that there had to be someone who said, “all right, this is the sacrifice that I am willing to make.”

Did you have any qualms about putting out a story this dark? Monsters aside, there’s a lot of scary stuff here.

I wrote the thing on Vulture that all these people were doing a shitty job for not being dark enough. I think there’s an honor to darkness, if I’m being frank. I think we live in a universe where the creative principle is as strong as the destructive principle. You can decide you’re not going to pay attention to this one thing at the expense of the other thing but then you’re half lying. Like, every baby that’s born has to die one day and I would say that’s fine. That’s actually kind of great. It’s a beautiful world that we’re a part of. The first has no value if you remove the other side of this equation. So you’ll say, you’re being really dark, but to me, the book also is a celebration of love.

Going back to determining what is the Gothic tradition, the Gothic tradition isn’t darkness per se, it’s looking at this polarity. How light is the light and how dark is the dark? In Hemlock Grove, the light is terribly brutally close.

What is monstrous in the novel?

The greatest degree of monstrosity is living inauthentically. If you take a model who weighs 97 pounds and is puking all the time and is doing a bunch of coke and is miserable, that to me is monstrous. Whereas if you get someone who is morbidly obese and is wearing nothing but Lycra and is like, “Fuck yeah, I’m hot shit” and believes it? That person’s a fucking hero. Because one is living authentically and the other isn’t. To me the monstrous characters in Hemlock Grove are the ones who are living inauthentically. Whereas characters that are literal monsters, they basically know who they are and how to live with integrity, which makes them not monsters in my estimation.

They have to hide a little bit.

Well, yes, that’s being an adult. Hiding is a conscious choice. I’m talking more people who don’t realize the self-deception in their lives. There was a Vimeo video that was being forwarded around my writing staff for the Netflix adaptation, a documentary about bestiality. There was a married couple being interviewed, a man and a woman, and the common bond between them was that both of them were being very honest and accepting of the fact they wanted to fuck a horse. And you’re watching them talk about this and I’m with my writers and I literally have tears in my eyes. It’s just so fucking beautiful, I want to punch myself. That is beyond great to me and sure, if they’re at a dinner party in front of a bunch of strangers they’re not going to say, “What brought us together as a couple was we both really like getting fucked by horses and when I see the bite marks from this horse on my partner’s back it just fills me with feelings of love and arousal.” You hide that for strangers but you still do it and you love that about yourself because that’s you and that’s authentic.

That’s, um, quite an example.

I stand by that example [laughs]. If you give me your email address, I’ll send you the link. Watching it, you’ll think, “This is one of the more unnerving things I’ve seen recently,” but there are plenty of people in heteronormative relationships that are fucking miserable and want to cut off each other’s heads. Joseph Campbell has a quote: “If you’re falling, dive.” So whatever is true to you, live that truth.

Desiree Browne asked her mom is she could have a séance at her thirteenth birthday party. Her mom said no and now she writes about less magical but still interesting stuff. Photo of Brian McGreevy by Rebecca Hickok.

Secrets Of The 'Hustler' Style Guide

“Well, of course every publication has its own internal style guide, and ours was more than hilarious. We had lists of euphemisms, paragraphs of them, for every body part you could think of. Phrases like cover girl, which in Webster’s are two words, were one word at Hustler. Blow job was blowjob. (See here for more examples.) And the style guide had been in progress since the 70s, so many things had changed over time. For instance, there was an entry under ‘Goddamnit’ that said the expression was never to be used in a Flynt publication without editorial approval — which I thought was kind of strange, considering everything else that was okay. I was told that the rule was left over from Flynt’s brief born-again Christian phase in the 80s.”

— The Last Word On Nothing’s Michelle Nijhuis interviews former Hustler copy editor Eric Althoff, who seems like a person who might be able to once-and-for-all settle the great fingering debate.

Customer Reviews For The Mother Casket From Costco.com, $949.00 (Plus Shipping And Handling)

by Alex Beggs and Jack DeLigter

• “Everyone was very impressed with the idea of a Costco casket.”

• “We decided to purchase the beautiful ‘Mother Casket’ after reading all 11 reviews with a score of 5 out of 5 stars.”

• “The mortuary was familiar with the BRING YOUR OWN CASKET (BYOC) — although they did not tell me when the casket had arrived.”

• “I think that my Mom would have been delighted with the purchase. She looked lovely with the lilac color of the casket.”

• “It was much easier than standing in a room full of caskets trying to choose one.”

• “I chose this casket for my mother based on the color and I can honestly say it was absolutely the best funeral decision I made.”

• “This is from someone who has connections within the funeral industry.”

• “I have never been disappointed with Costco’s services and products, but when it came right down to choosing a casket for my mother-in-law online, I was very hesitant.”

• “Beautiful casket at an amazing value, but the best part of the whole experience were the people I dealt with at Universal Casket and Costco.com.”

• “Even prettier than the picture!”

• “Con: Costco website tracking is not updated live.”

• “I would recommend this product to anyone.”

Alex Beggs and Jack DeLigter are editorial assistants at Vanity Fair magazine and can help you plan your next funeral faster than you can say “TurboTax.” They would like to remind you that The Mother Casket may cost $949.00 but shipping and handling is included!

Michael Fassbender Does An Excellent Robot

Wow! This new promo clip for this summer’s Aliens prequel, Prometheus, is super-creepy and great. I don’t know why the sci-fi folks always have to use this particular name in these nightmare-inducing scenarios, though.

What It Cost Eight Women Writers To Make It In New York

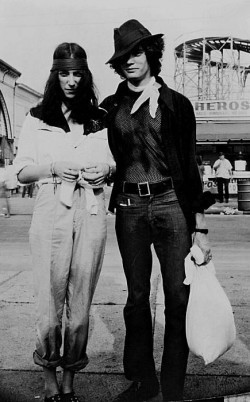

Top row: Dorothy Parker, Zora Neale Hurston, Shirley Jackson, Gael Greene.

Bottom row: Patti Smith, Susan Sontag, Tama Janowitz, Kate Christensen.

In 1967, Patti Smith wrote in Just Kids, she was considering a move to New York City. “I had enough money for a one-way ticket. I planned to hit all the bookstores in the city. This seemed ideal work to me.” Twenty-seven years before her, in 1940, Shirley Jackson and her soon-to-be husband Stanley Hyman graduated from Syracuse and moved to New York. According to this biography, “For quite some time they had known exactly what they were going to do: move to New York City, live as cheaply as possible, take menial jobs if necessary and wait for the Big Break. Not just wait — push for it.”

And fifteen years before that: “The first week of January 1925, Zora Neale Hurston moved to New York City, as she recalled, with a dollar and fifty cents in her purse, ‘no job, no friends, and a lot of hope,’” as one of her biographers put it.

The equivalent young female writer arriving in New York in search of literary success in 2012 (as calculated by the CPI Inflation Calculator) would have $19.51 in her purse, which could buy breakfast at Balthazar, or a pack of smokes and one Happy Hour cocktail, or about ten hours’ rent.

We’ve looked at how much the costs of things like Reeses peanut butter cups and TV sets have changed over time — very specific items. Let’s cast a wider net. For more than a century, the young flock to New York as the place to launch a career in the arts. Is it as expensive a proposition now as it always has been? Has the size of the potential rewards increased or decreased? And more importantly, just what was it like? In what ways was hanging at the Algonquin Roundtable just like (and not like) bumming around the lobby of the Chelsea Hotel? Let’s look at the Bohemian set over time, as seen through the eyes (and pocketbooks) of some of the women writers we’ve been reading for decades, from Dorothy Parker and Hurston onward to today.

The list of authors discussed here isn’t meant to be exhaustive, or even authoritative. There are many, many writers that could have been included in this survey, and any such omission is not intended as a slight (except to Ayn Rand, of course). Also different biographies are less forthcoming than others when it comes to specific dollar amounts, which was sometimes a factor in choosing subjects. Our intent here was simply to pick a writer or two from enough different eras to give a sense of what’s been involved in moving to the Big Apple to make it (or otherwise) over the past century.

THE RENT

The first concern of the new arrival is housing. Not to put too fine a point on it, but a young artist without a roof over the head will eventually be typing in the rain. And while couch-surfing (or whatever it was called before there was surfing) is attractive as a short-term solution, that’s a scenario whose charm wears quickly.

Dorothy Parker was not only the original New York scene denizen, she’s the most indelible. The Patron Saint of Getting Off the Good One, Dorothy was technically a New Yorker from the get-go, although she was born in the Rothschild summer residence in New Jersey in 1893. And the scene that she ran in was the famous Algonquin Round Table set, a group of New York’s allegedly best and brightest that congregated around a giant cornerless table in the restaurant of the Algonquin Hotel on West 44th Street (reopening in May!). These journalists, poets and playwrights included Alexander Woollcott, George Kaufman and Dorothy’s pal Robert Benchley. From here, that constitutes an Ur-Scene, the one that all the others compare themselves to — witty, talented, incestuous and inseparable, a whole greater than the sum of the parts. And (reluctantly) standing at the prow was Dorothy Parker, whose tenure at the Round Table seemed more a vocation than a lunchtime habit.

For details of Mrs. Parker’s life, we turn to Marion Meade’s bio, Dorothy Parker: What Fresh Hell Is This?

In 1927, separated from her Mr., Dorothy Parker got her own place, a furnished small one-bedroom on E. 54th Street in midtown. Both her office and locus for nightly pre-carousing cocktails, Parker paid $75 a month rent — $981.31 in 2012 dollars. If you see a Midtown one-bedroom for less than a thousand dollars I suggest you take it.

Of course living quarters should not go unadorned. In 1933, Parker attended an art exhibition for Zelda Fitzgerald. Parker was friends with F. Scott and his wife, and by that time Zelda was beginning the process of her crack-up (to be followed by Scott’s). At the show, Parker picked up two of Zelda’s oils for a total of $35. And while Parker thought them of quality, she also found them too disturbing to hang — perhaps no surprise, as of the many things that Dorothy Parker was, champion nester was not one of them. According to Meade, “So phobic was her reaction to domesticity that she would rather have starved before boiling herself an egg.” Were you to do the equivalent favor to a friend’s artist wife in rehab today, you would plunk down $612.94.

Around the same time, Zora Neale Hurston came to town. (For info on Hurston, we consulted Wrapped in Rainbows: The Life of Zora Neale Hurston by Valerie Boyd.) After a peripatetic early adulthood, bouncing between Florida and Tennessee, Hurston had shaved ten years off her age (from 26 to 16) in order to attend public school in Baltimore in 1917, eventually attending Howard University. But Opportunity, the journal of the National Urban League, had published Hurston’s short story “Drenched In Light” the previous month, so she packed up and made for the Big City. Little mention is made of the exact rents paid by Hurston (although there is, in classic writerly tradition, frequent reference to her being late on it), but it’s interesting to note a practice common to Harlem in the 20s and 30s: rent parties. For admission of pocket change, a fine party was thrown, with the proceeds going towards paying that month’s rent. Hurston herself, at about the same time Parker moved to E. 54th Street, threw a furniture party while moving into her new flat in the W. 60’s, with each attendee bringing one item of furniture. Just as Dorothy Parker’s apartment would become the treehouse for her coterie, Hurston’s flat would go on to be the equivalent locus of the Harlem Renaissance.

Shirley Jackson’s tenancy in New York was a brief one (according to the biography by Judy Oppenheimer, Private Demons), from 1940 to 1945. She and husband Stanley first landed at 215 West 13th Street, a short block between Seventh Avenue South and Greenwich, which was lined with the sturdy apartment buildings we call “pre-wars.” After a brief foray to a wooded cabin for the purposes of the quiet pursuit of writing in ’41, they returned to the city, with apartments in Woodside, Queens, and then back to the Village, on Grove Street. And as with Parker and Hurston before her, the Grove Street apartment became somewhat of a hub of frequent social occasion once Hyman’s (and later Jackson’s own) work began to appear regularly in The New Yorker, with new friends such as Joseph Mitchell, A.J. Liebling, Brendan Gill, even William Shawn. Oppenheimer describes these parties as, “never dull. Stanley was exuberant and argumentative, and both he and Shirley could be bitingly critical — it was a rare evening in which at least one person was not mortally offended.” Props to that. In 1945 they decamped for good, when Stanley was hired by Bennington College.

The first apartment that Patti Smith, poet, artist and member of the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame, and photographer Robert Mapplethorpe rented (when they were Just Kids, in 1967), an apartment that they saved money up for while relying on the kindness of friends for shelter, was 160 Hall Street in Brooklyn, not far from Pratt Institute, for $80 a month. They entertained friends there, much like Parker, Huston and Jackson before them, and Smith referred to these soirees as “loser’s salons.” Now, that rent would be $545. Let’s just say that Fort Greene is a little more pricey now. (Though to be fair, the property was most recently appraised at $646,000, which is an attractive price for a three-unit building.)

By 1969 Smith and Mapplethorpe had moved to a room in the iconic Chelsea Hotel on West 23rd Street in Manhattan, where Dylan Thomas lived before them and Sid and Nancy after them, and where artists from Mark Twain to Jackson Pollock to Vladimir Nabokov would stay on visits. The room ran $55 a week. The next year, they moved down the street into the second floor above Oasis Bar, which they partitioned into two spaces to accommodate their growing separate lives, for a rent of $225 a month. That was the last quarters they would share, though they remained lifelong friends (until Mapplethorpe’s death in 1989). Converted into current dollars, the rents would be $341 a week and $1,320 a month, respectively.

From the memoir of Sigrid Nunez, Sempre Susan, we get a window into the life of Susan Sontag, the Dark Lady of American Letters, in New York in 1976. Now, it may not be fair to characterize Sontag as a struggling artist in 1976 — she was already a public figure/intellectual for the past decade, had already famously visited Hanoi — but let’s remember that being a public figure/intellectual is not always as remunerative as one would think. Sontag’s apartment at the time was on the corner of Riverside and 106th Street, a two-bedroom penthouse on a block lined with more of those pre-wars, not far from the Columbia campus. Rent was reportedly $475, or $1,914.96 converted, which may seen like not so much the bargain, but if you’ve never seen a prewar two-bedroom penthouse apartment, think “mansion.”

More recently, Kate Christensen — PEN/Faulkner winner for The Great Man, and, most recently, author of The Astral — very helpfully posted a short bit (and, even more helpfully, was nice enough to answer a few questions via email) detailing the Rents That She Has Known, bouncing around NYC post-college. (If you’re not familiar with Brooklyn, you may want to skip over the street references here, but during that time I lived blocks away from Christensen so I’m fascinated.) In 1989, she rented a bedroom of an apartment on St. Marks Place between 3rd and 4th Avenues for $300 — of which apartment Christensen says, “Our windows had bullet holes in them; my roommate was mugged twice in front of the bodega on the corner; my boyfriend was afraid to visit me.” Nostalgia! In 1990, her one-bedroom on Graham off Metropolitan (currently Second-Wave Williamsburg nexus) was $350. In 1995, her place on N. Henry and Norman, the far reaches of Greenpoint, was $450. In 1996, she moved into her new husband’s industrial loft near Metro and Wythe, which went for $700. Respectively, those rents adjust to $550.80, $609.66, $672.23 and $1,015.70. And Christensen even provides her own current example, as, when she left Brooklyn in 2010, her railroad apartment near Monitor and Norman Streets was $1,800. Lesson learned: man, did we have it good in the 90s.

FOOD AND DRINK

The acquisition and consumption of the daily bread is an occupation for us all, of course, but for the recently arrived, it takes on a special light. These are basic needs, of course, but they are ancillary to Making It. Who has time to worry over the meat and the potatoes when the search for status looms, and when surrounded by such interesting friends? Not so much an afterthought, but something that happens in the back of the mind, frequently on the way to somewhere else.

Amidst the wisecracks and the bon mots hurtling back and forth, the room that held the Round Table was a restaurant, providing sustenance to the well-heeled clientele (and the Round Tablers). While Dorothy was more likely to rely on the charity of the hotel, happy to have a famous/notorious regular, the blue-plate special (half of a spring chicken, two veggies and French fries), was going for $1.65 in 1927, the height of the Round Table’s fame. Convert that into 2012 dollars and you get $21.59. True, the Algonquin would occasionally stand the bill, as the publicity brought by the celebrity of the Round Tablers was worth it, the Algonquin was decidedly not a diner.

Maybe the offhanded concern for a day’s worth of calories was due to their fondness for liquid refreshment. The Round Tablers, were pretty much souses to a man (or woman), and that was during Prohibition. And at that time, the Tablers weren’t exactly scouring the city for the cheapest Happy Hour. The bootleg Scotch that Dorothy’s first husband would pick up to keep the couple lubricated in 1922 was going for $12 a quart (a princely $162.62 in current dollars).

With Susan Sontag, again we suffer from the lack of a direct reference to price, but from Nunez’s Sempre Susan we have this tidbit on Sontag’s opinion of the formal dinner party, which brings to mind the entertaining of Parker, Hurston and Jackson:

It was sometime in the sixties, after she’d become a Farrar, Straus and Giroux author, and she was invited to a dinner party at the Strauses’ Upper East Side town house. Back then, it was the custom chez Straus for the guests to separate after dinner, the men repairing to one room, the women to another. For a moment Susan was puzzled. Then it hit her. Without a word to the hostess, she stalked off to join the men.

Naturally the meals of Gael Greene are more of a pronounced element in the story of Gael Greene’s life, as related in her autobiography Insatiable: Tales From a Life of Delicious Excess. She writes of a life of nascent gourmandism, growing up in Michigan in the 40’s, accentuated by a mid-college year in France with a one-month detour to Rome, where she learned how to feed any number of friends with a lamb risotto that she could whip together for a buck or two.

Even as her star as a magazine writer and restaurant reviewer began to rise, in the heady days of the ascension of New York magazine, Greene keeps an eye on the bottom line. In 1969 Greene wrote a feature called “The Menu Rap and How To Beat It,” a service-y little bit advising New Yorkers on how to downsize it up while styling and profiling at the more prohibitive of New York’s restaurants. For example, a meal for two she names “Four Seasons in Your Slack Season,” (from the Four Seasons, naturally) a chicken liver mousse to share, two quails en brochette and a pot of coffee come to $14.25, or $88.40 now. Not so slack, no?

In Insatiable, Greene mentions the price of a bottle of Chablis she and her first husband, journalist Don Forst, drank in 1962 while planning their belated honeymoon as $1.89, intended to demonstrate the modesty of her and Don’s pre-fame lifestyle. Was that in fact a Two Buck Chuck? At $14.25 in 2012 dollars, no it was not.

In 1967, Patti Smith, newly in New York and living in the streets, finds two quarters in the grass of a park, which paid for breakfast for her and her new friend/scout, Saint (who borders on the archetype of the Magical Homeless Person, but, hey, it happened). “Fifty cents was real money in 1967,” writes Smith. Fifty cents then is $3.41 now. Not what we would call real money — bagel with a schmear maybe, and hopefully with a free coffee regular? And two years later, she scraped together change and went to the Automat for a lettuce and cheese sandwich. She thought it would cost 55 cents, but the price had increased by a dime, so she was short. A gallant Allen Ginsberg, then a stranger to Smith, paid the difference and they ate together. The adjusted cost of the sandwich over which Smith was mistaken for an attractive young man? $4.03.

CLOTHES

Clothes are not a prominent element of many of the life stories we looked at, and happily so, as that’s not a stereotype we are excited to perpetuate. Wrapped in Rainbows does mention that in 1926, while Zora Neale Huston was at Barnard, admission to the Junior Prom ran $12.50, which we include as that is at least partially an apparel-related event. That converts into an even $162 now — prohibitive if you are pinching the pennies.

Gael Greene does mention being fashion-minded as a new New Yorker in 1957, reading “WWD religiously so [she] could decide which Yves Saint Laurent or Givenchy designs to look for when authorized $69.95 copies arrived at Ohrbach’s, the late, lamented discount temple on Thirty-fourth Street.” Haute couture knock-offs may be an arguable necessity for the new arrival, but the modern equivalent of that price tag is $566.73. (Yikes.)

A piece of jewelry was the MacGuffin of the secret origin of the friendship between Patti Smith and Mapplethorpe. In 1967 they met under random circumstance three times, the third time being the charm. The second time, Mapplethorpe came into Brentano’s, where a homeless Smith worked (and sometimes slept, hiding as they locked up the store). Mapplethorpe bought a Persian necklace that Smith had had her eye on. The necklace cost $18. The third time they met, Mapplethorpe gave it to Smith. This extravagant gesture would cost $122.69 now.

In 1973, Smith made a pilgrimage to the Ardennes of France to visit the birthplace of Arthur Rimbaud. To prepare for the voyage on the Bowery she purchased what she imagined as her wardrobe for the trip: “an unconstructed raincoat of Kelly green rubberized silk, a Dior blouse of gray houndstooth linen, brown trousers, and an oatmeal cardigan,” a previously-enjoyed ensemble that set her back $30, or $153.83 adjusted.

You’ve heard of novelist Tama Janowitz, of course. Amidst the books she has written (including the iconic Slaves of New York) is a collection of essays, Area Code 212: New York Days, New York Nights, which is rich in detail useful to this project. From the collection, we learn that when Janowitz was finishing college, she was developing the trademark style for which she was equally notorious as Slaves took off, buying (among other vintage curiosities) a black Balenciaga ball gown for just $2.50 at the Ladies’ Auxiliary thrift store in Flushing, Queens. She graduated Barnard with her B.A. in 1977, so we’ll call it 1975 when she bought the Balenciaga, which would cost $10.58 were it now. At that price, buy them all.

And Kate Christensen, while living at her St. Marks pad with the broken windows in 1989, got a pair of black Bandolino pumps for $80, to wear at her first Big City job. The job, however, was in publishing (“I didn’t realize everyone in publishing wore sneakers to work,” said Christensen), so she only wore them twice. Adjusted, that was a $146.88 investment in a future that did not come.

LIFE INCIDENTALS

Into each of these lives a little rain must fall. In between the exhilarating times there are the down-days, the accidents and the setbacks, minor and major.

Take, for example, Dorothy Parker. None of our lives are without their ups and downs, invited and not, but Parker’s downs were numerous and frequent. Given to both depression and a sharp case of dipsomania, Parker attempted suicide on more than one occasion. After one such attempt in 1926, she kept regular appointments with Dr. Alvan Barach (who would later go on to help develop the oxygen tent) as an attempt, which failed, at rehabilitation. Each hour-long appointment cost $25 (when Parker bothered to pay), which translates into the pricey $325.23 in current dollars.

A year later Parker found herself attracted to a political cause (shocking the Round Tablers, as Parker was not one known to have a political bent). Ferdinando Sacco and Bartolomeo Vanzetti were facing trial for a double murder and robbery that had happened seven years earlier. As there was very rabid anti-anarchist sentiment at the time (this would be the first Red Scare), supporters of the movement claimed that Sacco and Vanzetti were railroaded. The trial in Boston was heavily protested, and Parker was one of the celebrities (along with Edna St. Vincent Millay, Upton Sinclair and Katherine Anne Porter) who came to town to march in support of them. She was arrested on one of her first marches, and fined five dollars for “loitering and sauntering.” I’m not sure if the sauntering law is still on the books, but the fine converts to a present-day $65.42 — roughly a mild NYC parking ticket.

It did not end well for Sacco and Vanzetti, and that was not the last Red Scare that Dorothy Parker got caught up in, as her commitment to social causes and general left-leaning landed her on the Blacklist of the second Red Scare in the 50s. Her commitment survived her passing in 1967, as she bequeathed her estate to the NAACP.

When Patti Smith was making the big move, hoping for a life as a bookseller, she actually found that she did not have enough money for the one-way ticket. But she found a purse, underneath a public phone, that had not only a bus ticket in it, but also thirty-two dollars, which she described as “almost a week’s paycheck at my last job.” That ’67 $32 would be $218.12 now (obviously, this does not count as a calamity for Smith, but think of the poor lady in Philly who lost her purse).

Can a dollar amount be placed on affairs of the heart? Not so much, but it’s worth a mention in the spirit of intrepidness. Some of our subjects ended up in long-term relationships that lasted for decades — Shirley Jackson, for one, remained married to Stanley Hyman until her death in 1965. On the other hand, take Zora Neale Hurston, who was twice married, the first time for four years and the second for seven months. And of course in the early years for our subjects there is the requisite amount of Hooking Up. Dorothy Parker was said to have had affairs with the bulk of the Round Table; Patti Smith was linked to Mapplethorpe and Sam Shepard (before marrying Fred “Sonic” Smith in 1980 and remaining so until his death in 1994). And the dalliances of Gael Greene you might have heard of, as they included Clint Eastwood and Burt Reynolds (each the subject of magazine features Greene was assigned). Greene, you may remember, also gained a certain notoriety for publishing very forward erotic novels in the 70s (Blue Skies, No Candy and Doctor Love).

Though sometimes the unintended consequence of the roll in the hay carries a price tag, real or emotional. Before Smith left New Jersey for New York, she found herself unexpectedly in a motherly way at age 20, a baby she gave up for adoption. And Parker’s relationship with playwright Charles MacArthur in 1922 (before her marriage to Mr. Parker had ended, by the by) resulted in an abortion (about which Parker quipped that it served her right for putting all her eggs in one bastard). It was rumored that MacArthur kicked in thirty dollars for the procedure, which would be $406.54 now.

THE DAY JOB

Eventually the young arriviste turns her eye to getting paid. All the apartments, the meals, the hooch, the Balenciagas — they don’t pay for themselves. Hence, the day job and the general hustle for scratch, all in hopes of that first check for something the artist actually came to New York to do in the first place.

It’s difficult to separate the pre- and post-success life for Dorothy Parker, as her first sale predates her employment, and her employment was tied in pretty tightly with her writing. But shortly after she sold her first poem in 1914, Parker was hired on the staff of Vogue, the sister magazine of Vanity Fair for $10 (or $225.41, adjusted) a week. She continued to contribute to VF, and began to be assigned feature writing in 1917. Months later she was transferred full-time to VF, where she would meet Robert Benchley in 1919, when he was hired as managing editor for a salary of a hundred dollars a week (or $1,325.97 now).

Sometimes deductible expenses were incurred. In 1920, Dorothy had been let go from Vanity Fair (to make way for the return of P.G. Wodehouse, whom she’d replaced), and Benchley, Mapplethorpe to Parker’s Patti Smith, joined her by resigning in protest. In pursuit of freelance work, the two decided to rent their own office, a very modest closet-sized space in the Metropolitan Opera House studios. (“An inch smaller and it would have been adultery,” said Parker, an adultery which no matter how widely talked about was deemed unfounded by Parker’s biographer, Marion Meade.) The rent? Thirty dollars per month, which works out to be $341.49, which seems to be about what a desk in a workspace might cost now in Brooklyn Heights, or maybe in the Fashion District.

In the case of Zora Neale Hurston, her early life was a little hand-to-mouth. Born in Florida and raised in the Jim Crow South, one of her earliest recorded jobs was as maid to the lead singer of a traveling Gilbert & Sullivan troupe in 1915, for ten dollars a week plus room and board. Now that would be $225.41. Later, after initial success while in New York proper, she found that the writer’s paycheck was not sufficient to make ends meet. She was then staked by her benefactress, philanthropist Charlotte Mason, who, both born and married into wealth and obsessed with “primitive” spirituality following the death of her husband decades before, was “Godmother” to many in the Harlem Renaissance. In 1928 Mason hired Hurston as a researcher, to travel throughout the South collecting African-American folklore, for the salary of $200 a month, which converts to $2,662.73 now.

Shirley Jackson, in the 40s, suffered many a menial job. Jackson, mocking her own c.v., wrote, “I am twenty-three, just out of college, authority on all books and great writer, can type, cook, play a rather emotional game of chess, and have a republican father, which is no fault of mine.” One of these jobs was a brief stint selling books at Macy’s (bookselling being a recurring theme here). One of husband Stanley Hyman’s first jobs is also a matter of record — in 1940 entered and won a New Republic contest, which magazine then offered him a job (which he took) as editorial assistant at $20 a week (which works out to be $327.30 in 2012 dollars).

According to this New York feature, Nora Ephron, arriving fresh from Wellesley in 1962 on her way to a full-time reporting gig for the New York Post (and eventual long career in the motion-picture business) was first a mail-room girl at Newsweek, for the weekly salary of $55. Were that Wellesley girl making the current equivalent after making the move from Massachusetts, she could expect $414.62 a week, a little more than ten bucks an hour for a forty-hour week.

Gael Greene, in her autobiography, describes her reaction to being asked to write for Clay Felker’s new magazine, New York. Greene was already a successful freelancer, with bylines in big ticket mags like Ladies’ Home Journal and Cosmopolitan, and was concerned about the size of her Felker paycheck. “The word was that everyone at New York, star writers and unknowns alike, would be paid the same puny three hundred dollars an article till the magazine began to make money,” Greene writes. This was 1968, so that puny $300 would be a puny $1,954 now.

Meanwhile, that same year Patti Smith landed her second bookstore job, at Scribners, and the salary of $65 a week made her the breadwinner of 160 Hall, while Mapplethorpe made art. That works out to be $428.46 now. (For purposes of illustration, a forty-hour week at the current federal minimum wage would net $290.)

And the publishing job for which Kate Christensen bought the pumps? That was as an editorial assistant at William Morrow (a nice place to start, yes?), for a 1989 salary of $17,500, which would be $32,129 now.

MAKING IT

Hopefully the day that comes after the dingy apartment, cadging meals and punching the clock is the day that first check arrives, compensation for the first byline, or the first story. And even more hopefully, that day is only the first of a long march of such days.

The first piece that Dorothy Parker ever sold, a nine-stanza poem called “Any Porch,” was bought by then-new magazine Vanity Fair in 1914 for twelve dollars. Remember, that was a time in which poems were more widely published (as in, by more than just The New Yorker). In fact, Parker’s celebrity (and she was no doubt one, in the 20s and 30s) was built more on her verse than on her prose. (Yes, you may be sick of hearing, “Men seldom make passes/At girls who wear glasses,” cited as representative of Parker’s talent, as well you should.) Nevertheless, that first sale converts to $273.20 in current dollars, or thirty bucks a stanza.

In 1925, soon after arriving to the city at 34 (which should reassure you late-bloomers), Zora Neale Hurston won more prizes than anyone else (more than Countee Cullen, more than Langston Hughes) in Opportunity’s first literary contest — two second prizes and two honorable mentions, one each in short story and drama. Each of the second prizes brought an award of $35, or $455.33, adjusted. Hurston’s first novel, Jonah’s Gourd Vine, was published in 1931, for which she received an advance of $200, or converted, $2,995.57. (How is it that the same $200 is worth more in 1931 than in 1928? The Great Depression, which was a time of monetary deflation.)

In 1941, while on austere retreat in New Hampshire with her husband, Shirley Jackson sold her first piece, a short comedic piece titled “My Life With R.H. Macy” to the New Republic. It was an apt recount of her experiences while selling books at Macy’s, and it brought with it a fee of $25 (or $390.12 in 2012 dollars). I’m not sure, however, how much that is translated into New Hampshire dollars. “The Lottery” (which is the most harrowing thing you read in high school) was first published in the New Yorker in June 1948, and her first novel, The Road Through The Wall was published later that year for an advance of $500, or $4,759.17 adjusted.

According to Area Code 212, in 1986 Tama Janowitz (who had partly supported herself with fellowships and prizes post-college) obtained with the help of her agent an advance of $3,500 for Slaves of New York, the novel that would put her on the map (and into the largely manufactured “Brat Pack” along with Jay McInerney and Bret Easton Ellis). That converts into $7,270 now. Her next two books were pre-sold (at the same time as Slaves for $20,000 apiece, or $41,544, which seems more like it, but when you take out the taxes and the agent’s commission, not so much. Especially if it takes more than a year (or two) to write the novel, that’s not exactly enough to rush out and buy yourself health insurance.

Kate Christensen’s first story was published as the winner of a Mademoiselle fiction contest in 1988, which brought her an award of $1,000, which would be $1,924.24, now (“It saved my life,” Christensen wrote to me in an email). And a year later she placed her first piece in Seventeen, a 100-word assignment on architect Maya Lin, for a dollar a word. That converts into $183.60 in 2012 dollars. I did not ask her about her book contracts, as it seemed tacky.

SCRAPING BY

In an essay reminiscence of the New York City art world in the early 80s, from her Area Code 212 collection, Janowitz writes, “I was in my twenties and felt embittered that I had missed the Real Thing — the Real Scene — by more than a decade.” Maybe that’s a strange argument for Janowitz to make, considering how Slaves of New York transformed wherever she was once hanging out into the Real Scene, at least in retrospect. (For example, the next piece in the book details the Blind Date Club, which consisted of Andy Warhol taking Janowitz and Paige Powell out on a weekly dinner with various and random blind dates — if Warhol is not the Real Scene, then who is?) But is that the appeal of moving to the big city? Is the goal success, or is the goal the richness of experience that happens in the pursuit of that? It may be a career decision, but it’s certainly also a lifestyle choice, and I will do the favor of not referencing a certain Sunday television show pertinent to this discussion. And is that why the influx of young writers to Gotham continues to this day? I think it’s safe to say, looking over the data, that while bargains can be had (I’ve had them too!), living in NYC is and has been an expensive proposition, and while a tenable standard of living has historically been obtained, as demonstrated by our subjects, Making It is one of the harder things in the world (and that’s before we even begin to talk about things like talent).

Writing about her early time as a writer, Janowitz ends a reckoning of how little money she made compared to what she’d have made with a more cut-and-dry career observing, “As for advice, I only offer this: Mamas, don’t let your daughters grow up to be writers.” Apologies to Willie Nelson, but if it’s piles of cash that the young writer is imagining that await in moving for the bright literary lights of New York, that’s sage. But maybe everything else, the Real Thing-ness, makes up for it. It’s hard to avoid having to scrape by, seemingly at any age, and maybe one’s own Algonquin Round Table is more than a small comfort.

Related: How Much More Do Books Cost Today?

Cheese Grilled In Van, Exchanged For Money

“A chef from Brooklyn, New York USA, has turned a used NYPD van into a grilled cheese business on wheels.”