Banker Street, Brooklyn

Illustration: Forsyth Harmon

One of those days when the weather is so good it’s mindless. The relief of it, of warmth and sunlight and being outside, was stupid. It made everyone goofy, like we were all swilling coins in our palms, wondering where to spend them. Women walking with the private scandal of their winter legs, spring-bared, in sandals. Men with loose grins on their faces, staring about and seeing each other like they’d just remembered about people, a dumb wonder to it. Those grins catching and crossing through the streets like looped bunting.

You, an elf of a man in giant headphones, jeans rolled, aviators on, were oblivious to this. You were also, in your oblivion, the perfect embodiment of the day because you were dancing down the street. The feast of your moves, the sheer generosity of your repertoire, made me think you’d done this before, that this was just how you chose to get around on days like this, when the weather behooved you. Some people biked, some people walked, you danced. You were ten or so paces in front of me and I stared at a messenger bag the size of a baby packed at your back. Across it, a huge sticker that said — or exhorted — “HYDRATE”. Yes, I thought, that would be important if this was how energetically you chose to traverse a street.

I tried to mentally record and classify all your moves. A goblinny little waddle, with a rapid side jiggle of the head, like, I’m coming to eat you, haha, not really. A “teehee” made physical. A buoyant skip whose aerial-to-earthbound proportions were a trick, or a tease to gravity. The top of each bounce had a tiny pause like an exclamation point. Forefingers pointed upward, twirling, like, I see you sky, I see you sun. Sassy, vogue-ing shakes of wrist. You moved more like an animation than a man. Like an animation, you just went on and on, tireless.

To watch you dancing down this street was like watching Simone Biles do that tumbling flip of hers that’s impossible enough to be eponymous. Brain says wow no way. Body, wanting to feel it so badly, body, in its hopeless empathy, says, could I, couldn’t I? How many people can do “The Biles”? Same number of people who could dance like you. The idea was beyond my bodily imagination and yet my body tried. Not to actually physically copy you, to Pied Piper along behind you in tribute, but just to imagine.

It was so good, this whole spectacle of you, all the brunch-bound couples turning to gape at you as you passed, that I felt it belonged in a movie, or at least a viral video. I reached for my phone, then let go of my phone. You kept dancing, all the way down Franklin, all the way down Banker, until I lost you.

Personal Space

The Adventures of Liana Finck

Liana Finck’s work appears in The New Yorker and Catapult, and on her Instagram feed. Her first book, A Bintel Brief, was published by Ecco Press in 2014.

Six Weeks Later

A reflection in verse

Every couple days or so another thing emerges —

a place where all the crookedness and turpitude converges

“This,” you think, “will be the thing that brings the whole deal down

There’s no way after this that they could still support this clown

Our basic human honesty requires them to admit

that this is a transgression even they cannot acquit”

But then you look around and start to see the way we’re stuck:

They hate you and the country and they just don’t give a fuck

They want to watch the whole thing burn, there’s no way they’ll revert

They don’t care what this con man does so long as people hurt

There’s nothing too offensive with which they would not collude

They’ll cheer him as the missiles fly, and that’s why we’re all screwed

T.Raumschmiere, "Wacker"

Oh boy, you’re still alive.

Everything is terrible in its own sick way, but it’s Friday. Even though Mondays and Fridays are now the same day that still has to count for something. I don’t know. What do you want me to say? You know what’s happening and what’s going to continue to happen. Is there anything I can tell you that will make you feel better? Of course not. Well… this music is really good. That’s what I’ve got. Enjoy.

New York City, March 1, 2017

★★ A thunderclap sounded and the rain, already solid, turned heavy. A man in a suit stood poised at the edge of a scaffold, in the middle of the sidewalk, unfree to take the next step. Out on Broadway another man was on the move wearing a plastic shopping bag as a bonnet. Rain-spattered passengers mixed with longer-riding dry ones on the train. Powerful foul odors swelled in the subway stations. A vendor was out hawking Fivedollaumbrella, umbreallafivedolla. The rain gave out and sun crept on. Purple and pink blended seamlessly out beyond the far end of the cross streets.

Everyday Heroes

“24: Legacy,” “Quantico,” and Islamophobia onscreen.

The first time I visited a mosque, I was twenty. I was not, am not, particularly religious, but a Muslim friend of mine was passing through Houston, visiting family from the East Coast, and in the middle of a nothing afternoon, smoking mints up and down Midtown, he asked if I’d ever been to the city’s Islamic Education Center. I didn’t know what a mosque looked like, or where it would be, or what to expect, because the only Islamic centers of worship I’d seen were on television, and in theatres — plopped handily over green screens, coated under layers of artificial sand. But Ivan grabbed his hoodie, and his keys, tugging my phone from his charger, and said we’d make it through afternoon prayer in under an hour if he sped.

My working knowledge of Islam was built on absence and erasure: I hadn’t been exposed, and I hadn’t sought it out either. I’d sooner have sooner caught dinosaurs or talking fish on film than a thoughtful depiction of life in an Arab country — and what little exposure I could find was compartmentalized and packaged for chaos.

By and large, geopolitical thrillers in the 2000s meant white men navigating a terrorist plot in the making by brown/black/Asian folks, or white men in the midst of enduring some sort of active terrorist plot by brown/black/Asian folks, or white men plotting retribution in the aftermath of an act of terror by brown/black/Asian folks. And while the need for an other-ized villain extends to the very origins of American cinema, Islam and the Middle East in particular (and brown faces in general) are disproportionately cast in the light of danger — people to be avoided, apprehended, or foiled. Your princess needs saving, and it’s the hairy brown man holding her hostage. Your globalized investors are seeking protection from faceless insurgents of the east. The planet is under attack from some intergalactic scourge, brown bodies, imminent threats both near and far.

In this way, FOX’s “24: Legacy” presents yet another problem. As an offshoot of the original “24,” the series’ plot is rooted in similar territory — which is to say it doesn’t really matter much at all. It can be safely placed in the bucket of Tuesday-night counterterrorism. The show’s antagonism is a decidedly jihadist threat overshadowing the country’s intelligence agencies, only this time there are also Inner City Threats to navigate (gangs), a connection that surely made sense to the writers because the protagonist is black.

“Legacy”’s central problem, as ever, stems from those all-encompassing “terrorists.” We are told there are sleeper cells working amongst the protagonists. A major character’s attendance of a presently radicalized mosque is used as political blackmail. There are the show’s usual questions regarding continuity (if we’re experiencing 24 hours over the course of 41 minutes, how long is each minute?), and plausibility, and causality. While the series occasionally encourages some semblance of thought (To what extent do your personal allegiances supersede your country’s best interests?), it simultaneously discourages too much of it, because it mostly assumes in its audience a latent unease with Islam and brown people (and, as if to drive the point home, “Legacy” recently used live footage from Nairobi’s 2013 Westgate mall shooting to further a half-baked point — FOX has since “apologized” for screening the footage, in which at least 67 civilians were killed and 175 were injured).

Primetime television, for all of its frivolity, is a still a tool and an influencer. Simply put, visibility matters. Reverberations of the empowerment illustrated in Shondaland, or “Fresh Off the Boat”’s pokes at assimilation, or “Jane the Virgin”’s domestic absurdities, or an office discussion on “Black-ish”, or a relatively chaste kiss on “The Real O’Neals” are felt deeply and immediately. Their stories matter because we make them matter.

ABC’s “Quantico,” despite its own narrative shortcomings, is another example of harnessing and subverting that visibility — a young half-Indian* woman, Alex Parrish, is a top recruit for the FBI tasked with protecting a government that wants to eradicate her. The series opens with a literal explosion, with our protagonist at the center, and she spends many episodes attempting to convince her (mostly white) colleagues that she’s innocent of the subterfuge that follows. “Quantico” may be tacky in its approach, but it is remarkable for if no other reason than the fact that its writers actually went and pulled the damn thing off: brown people are both the series’ instigators and its saviors. Had the narrative threads been pulled tighter, “Quantico” really could have been something to behold — and yet, it still is, for the simple fact of its existing at all.

This isn’t to say that all storylines should forever cast every minority in objectively positive lights; on the contrary, ambiguity is illuminating. But it is foolish and destructive to act as though the entertainment industry isn’t as responsible for bending the tide of public perception as any executive order. The difference might not be tantamount to the man who suddenly realizes his Syrian neighbors are human too, but what will always matter is the banality that televised recognition applies. It gives you pause, those pauses becomes moments, and those moments make up a life. None of us is more than a conduit for the narratives we’ve consumed.

What Makes the Muslim Ms. Marvel Awesome: She’s Just Like Everyone

The happy medium just might reside in a narrative like Ms. Marvel’s: a young woman named Kamala Kahn is charged with defending her city from mutant and extraterrestrial threats — not because she is Pakistani, or Muslim, or even a talented young woman in an unpredictable comic book city — but because her idol did the same, and every teenager needs an altar, and while Kamala’s religion certainly informs her narrative, Ms. Marvel’s narrative isn’t solely informed by her religion. Kahn is a complete person. We’re given her successes, falsehoods, and faults. Ms. Marvel is a young Arab-American’s coming-of-age, miracles, mistakes, and all.

Our drive to the IEC off of Westheimer Road wasn’t very long, and the building was unassuming. A woman in the lobby welcomed us, and Ivan slipped into the group kneeling behind her. I knelt in the back, and he prayed for some time, and then he finished, and we left. Afterwards, Ivan took me to a diner for cheeseburgers and fries. He asked me how I felt; I said I was fine, and he nodded. That was good, he said, because he’d been worried — he said you never knew how someone would react. We talked about the World Cup, and the weather, and everything else but the mosque. It was simply, then and now, a beautiful place that we’d gone to. Ivan left Houston a few days later. It took a few more weeks for me to realize how rare of a moment it was, and a few years more after that for me to come down from the anger it brought.

There’s a moment near the end of Mohsin Hamid’s novel, The Reluctant Fundamentalist, where the narrator, having experienced the full brunt of “American exceptionalism,” comments on its implications:

It seemed to me then — and to be honest, sir, seems to me still — that America was engaged only in posturing. As a society, you were unwilling to reflect upon the shared pain that unites you with those who attacked you. You retreated into myths of your own difference, assumptions of your own superiority. And you acted out these beliefs on the stage of the world, so that the entire planet was rocked by the repercussions of your tantrums, not least my family, now facing war thousands of miles away. Such an America had to be stopped in the interests not only of the rest of humanity, but also in your own.

In a moment where the very language we use to ascribe legitimacy to a piece of information is being questioned, it can be tempting to succumb to the notion that our narratives are changing too. But that isn’t the case — we control the stories we put into the world. All of it counts, and the condensation of bigotry, and hate, and fear bottled into hour-long propaganda commercials infects every eye it crosses. “24: Legacy” alludes to a very particular nation-state — forever-warring, consistently tumultuous; with distinct, clear-cut racial and religious compartmentalization — a country that doesn’t exist. But the image still festers. It leaves an imprint. It sticks with us in our grocery stores, and our schools, and our subways, and our voting booths, and the streets many took to afterwards.

Two Muslim boys find solace not in their city, but in each other. A Lebanese family recounts their history as life in the States imprints itself across their lineage. A young hacker in unnamed country attempts to cripple an authoritarian government, combat a burgeoning culture of censorship, and still live out his bildungsroman. What makes us American — the thing that’s supposed to make us unique — is that anyone can play the hero. Anyone of us can don the cape. And until the country’s pop culture allows Muslims the benefit of the doubt, it will remain no less culpable than the entities near and far doing their best to divide us.

*Correction: This post originally identified Alex Parrish as Pakistani. She is half-Indian. The Awl regrets the error.

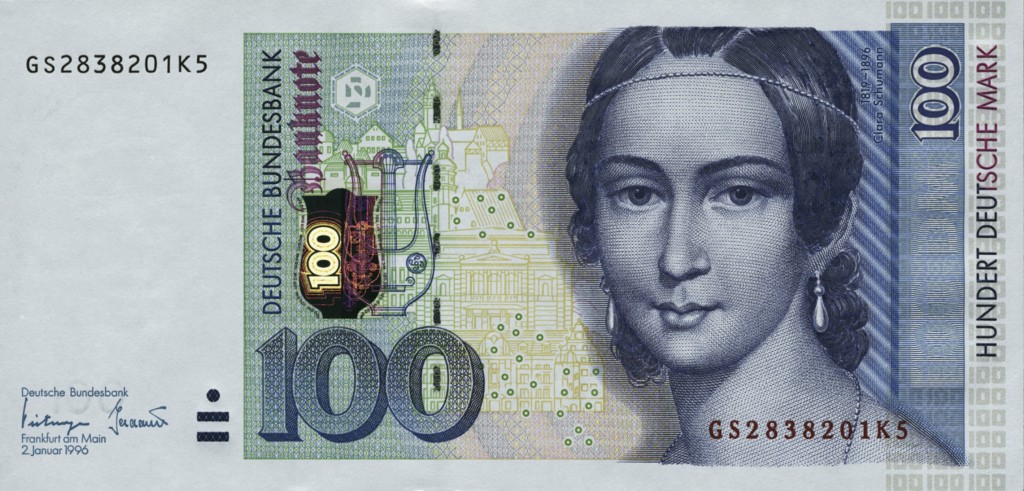

I Read A Book About Brahms And All I Got Was This Obsession With Clara Schumann

The main thing to know about me right now is that I am neck-deep in this Brahms biography. I am on a Brahms train, baby, and the next stop is 500 more pages of Brahms. And while every single fiber of my being is screaming, “write about Brahms this week,” I also know that I’m going to be tempted to write about him for the next month. So in the meantime, I want to write about one of his closest friends and maybe maybe maybe the love of his life, as well as the first female composer for this column: Clara Schumann.

Schumann (née Wieck) was born to be a famous pianist, namely because her father decided at a very young age that that’s what his daughter was going to become. He had her learning piano when she was a toddler, and even before she was 10, Clara was recognized as one of the most promising musicians of the mid-19th century. When she was 11, she met Robert Schumann, who was 9 years older than her, who dropped everything to move into her house and teach her piano and one day marry her. Nice. Nice nice nice. Extremely normal and good thing from the past.

The Schumanns are often recognized as a power couple of the time — your Beyoncé and Jay-Z, your William H. Macy and Felicity Huffman, you get it. But like many celebrity power couples, the woman is often more notable than the man. For a long time, it was easy to overlook Clara Schumann; Robert was the composer of them, really, and she was just the performer. But that’s wrong! It’s extremely wrong! She composed too! She performed all the time! Robert went insane (got mercury poisoning? Had syphilis? Who even knows when you’re living in the past, baby) and threw himself in the Rhine, while she went on to raise their seven children while also almost constantly on tour. (Okay, so a nanny or something like that probably raised those children, but you get it!!)

Descriptions of Clara Schumann in my big Brahms book are fairly consistent: she was serious, melancholy, only ever truly happy when playing piano but also constantly crying anytime she wasn’t playing piano. She and Brahms met through Robert when Brahms was only 20 (very hot age to be) and the two were inseparable for approximately two years while her husband was in an asylum. While they probably didn’t ever consummate their relationship, she did write him letters that said things like, “every letter from you is like a kiss.” In addition, there’s a brief but wonderful quote from Franz Liszt in this book, who at one point wrote of Clara as, “a consecrated, faithful stern priestess whose eyes look upon men with a sad, penetrating gaze.” Obviously, I love her.

The piece I found myself most drawn to her in small but significant repertoire is her first and only concerto: Piano Concerto In A Minor, Opus 7, composed when she was a mere 16 years old. So this is pre-Brahms, pre-Robert Schumann. This is Clara as Clara Wieck, and her work is still clearly steeped in a certain seriousness and straightforwardness.

Some context, perhaps, in her work is necessary: following the death of Beethoven (one of whose piano concertos I’ve previously written about), there was much to be figured out about the state of German music. Was it going to follow in the footsteps of ol’ Ludwig Van — fairly traditional meditations on a normal classical? Or would it move in the direction of composers like Liszt and Mendelssohn and Wagner, the early German Romantics?

Clara’s piano concerto comes approximately 8 years in history after Beethoven’s death, and even the opening movement, an Allegro Maestoso (!) feels fairly Beethoven-esque. It’s powerful and serious, heavy with emotion and straightforward with its themes. However, when the piano slinks over the orchestra around the 1:20 mark, there’s something much more delicate and coy. Clara’s music doesn’t feel as overtly tragic as Beethoven’s often did. There’s a little run at the 1:50 mark that’s purely joyful. So much of this movement in particular transforms into something lovely. I don’t mean to diminish her work as only lovely, please believe me. I just feel the urge to fight against this perception of her as this cold, mean woman. Look at this teen! Look at her write something so complex and genuinely beautiful! No German composer deserved her, as far as I’m concerned.

The first movement in fact leaves off on something of a cliffhanger, tumbling into the second movement, a Romanze. This is the shortest of the three movements, and it is a romance if I ever heard one. It’s meditative and hopeful! Hopeful! She wrote this with the help of Robert Schumann and it’s possible, no doubt, it was about a romance with him. She could have been crushing, is what I’m trying to say. Regardless, there is a cello solo that comes in at the 2:20 mark that, in tandem with the piano, is one of the most gorgeous and elegant melodies I’ve ever heard.

The original theme from the first movement returns in the third movement, an Allegro non troppo. It’s hard not to love the final movement of any piano concerto, in which just about every single piano part just goes right the hell off. I’m talking runs and sweeps and scales and just about every hand slamming down on the instrument all at once. No doubt there is some power in this movement. We’re back to that general Beethoven-y sound, this bubbling complexity, the back and forth between the piano and the orchestra.

There’s a part right at the 7 or so minute mark where it feels like the piano and the orchestra are talking to each other — not quite fighting, but certainly dancing around each other, about to square off.

I truly cannot believe Clara started working on this before I even had my learner’s permit, but there you go. The Allegro non troppo reaches a tense finale — it’s a balancing act, no doubt, between the lightness of the piano and the heaviness of an orchestra, like someone pulling on a tightrope as an acrobat walks across. The last minute on that piano is just — it’s insane. It’s amazing. It’s playful and forceful all at once. I’m so proud of her, this melancholy teen who would later own Liszt by simply looking at him. Women rule.

Fran Hoepfner is a writer from Chicago. You can find a corresponding playlist for all of the pieces discussed in this column here.

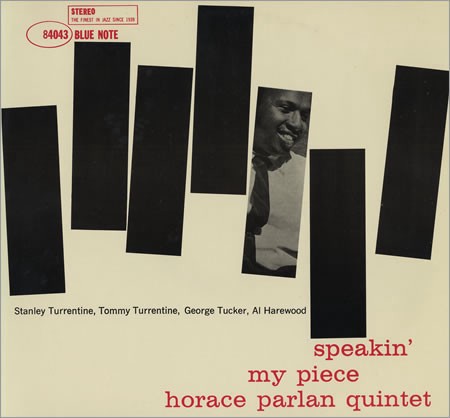

Horace Parlan, 1931-2017

And now he’s dead.

Parlan had a run of terrific records as leader for Blue Note in the early ’60s. Here’s the title track to 1961’s On the Spur of the Moment.

Parlan was 86.

The Uber Problem

Well, one of them, at least.

Have you heard that Uber has been having some issues lately? Money guy Matt Levine has a thought that is related, but also relevant to a larger issue with the idiot way the world works now:

Uber solves all its problems with money, which is not a long-term sustainable approach. As a consumer, I kind of hate this approach. Uber “attracts customers by offering them below-cost taxi rides,”… but that’s not how it attracted me. It attracted me with convenience and certainty and the ability to get a car anywhere. I would pay more for that than I would for a regular taxi. Instead I have to pay less, and make up for it with intense feelings of shame and guilt. This seems like a general problem with the current generation of tech companies. They’ll give you an incredibly valuable service for cheap or free, but they’ll make you feel terrible about it. (Hi, Twitter!) I feel like there is a market niche for more expensive products without the baggage, but perhaps that doesn’t scale.

Yeah, good luck with that. Thank God we’ll all be dead soon.

A Poem by Jennifer Michael Hecht

Swastikas Markered on the 1 Train

I own my own pre-existing condition,

riding under apocalyptic preconditions.

Are there any new laws against us today?

Isn’t it fun to be a Jew today?

“Apophenia,” our brains see patterns.

But there are other patterns.

Isn’t it strange to be despised again.

Historically, anything may happen.

Nothing always happens.

Just because it is happening again.

Jennifer Michael Hecht’s most recent poetry collection is Who Said (Copper Canyon Press).