Bad News Brenda

by Anne Helen Petersen

The first in a two-week series on the pull of bad influences in our lives and in the culture.

Brenda looked great in a bikini. She looked great in everyone’s bikini. She looked like an adult in a bikini, which is to say that she looked like one of those models we call beautiful because they have the face of an adult and the body of a 15 year old.

Brenda was equally great on four-wheelers and horses, and when she got her license, just months after turning 15 (Idaho doesn’t care about your national traffic safety), she’d already mastered the stubborn clutch on one of her dad’s vintage Land Cruisers that littered the pasture behind her house. She had a slight Southern accent from her formative years down south, and that sort of natural, incandescent blonde hair that people pay thousands of dollars to recreate. She had four stair-step sisters and a mom who looked young enough to be her sister, and one time they all went to a mall, somewhere down in Utah, and got glamour shots. Full blow-outs, draped-satin, air-brushed glamour shots. Brenda gave me one after I had become inculcated into the family and I put it in a fake gold frame I had bought from Shopko, which is like Wal-Mart’s skanky cousin. Her legal name wasn’t actually Brenda. It was BrendaJo. One word. That should tell you some of what you need to know.

Brenda was also an expert at sneaking out, lying, and doing drugs of unknown provenance. And for a period of twelve months, she was my sun and stars. My mom, unknown to me, called her Bad News Brenda. Moms know things that 15 year olds do not.

But Brenda wasn’t always bad. She grew up Mormon in Texas, and when her father finished his degree, she and her five siblings came to Northern Idaho, where they moved into a massive, rambling Mormon ranch house. The previous owners had even more kids than Brenda’s family, and the basement of the house was a labyrinth of children’s rooms, each with a slender window egress. At the far end of each hallway, there were two full bathrooms, back to back — mirror images of each other. Eight bathrooms in total. It boggled my mind. Under the stairs, a staggering cellar was filled with enough food to last a year. It’s a requirement, I learned, of all practicing Mormons — you need enough stored to survive the End Days. We regularly raided it for Ramen.

There was a poster on the wall of a man walking through three arches: red, blue, green. And then a planet. I didn’t realize until later that the poster represented the Mormon understanding of the path towards heaven. Despite my Presbyterian upbringing, I’d go with Brenda to church on Sundays. When I put on my frumpy church skirt her mom made me wear one of Brenda’s that went to my ankles. Plus pantyhose. For communion they took water instead of grape juice. It was odd, but ignorable.

Then Brenda’s dad left and was excommunicated by the church, but somehow her family situation did not look like disaster. We’d go out with the sisters and buck bales for the horses. We’d drive to nowhere in the Landcruiser, listening to Tupac, and just not say anything whenever the swears came along. Off-brand Slurpees were 79 cents. I loved how big her family was, how we’d all cuddle together and watch PG-13 movies, how the sisters shared a communal closet. I loved when we’d pile in her mom’s suburban and sing to Celine Dion’s “It’s All Coming Back to Me” and a ridiculous ’70s compilation with “Hooked on a Feeling.” As always seems to be the case in situations like this, I didn’t fall for Brenda so much as I fell for her family.

The ranch house had a pool and Brenda had a cool, hot mom and after the Friday night football games there were hundreds of kids flirting and pushing each other into the water. Believe me when I tell you there was not a beer, cigarette, a joint on the land. Knowing what I know now, this seems incredible. At the time, it was just my psuedo-Mormon life. I slept over on weeknights because why not. We’d drive early to school, she’d go to Mormon pre-school school, and I’d fork over two quarters for Egg McMuffins in the school cafeteria with the kids who got them for free. It wasn’t a bad life.

But Brenda was too beautiful. She was that ripening-too-early beautiful, like the subject of a Faulkner novel. Sometimes she’d sneak out of that slim bedroom window when I was sleeping in her bed, knowing her mom wouldn’t worry because I was there. I was, in essence, her insurance. Brenda understood this agreement better than I did, although I don’t think she ever maliciously exploited it. She wasn’t that kind of mean girl. She wasn’t a mean girl at all. Which, I hope you can see, is why I wanted so desperately to protect her.

As for her exploits, I never said a word — if I did, I knew our endless playdate would end. A playdate filled with her beautiful sisters, of course, but also with an automatic place at the high-school table. For the first time since becoming a teenager, I knew who I was: I was Brenda’s best friend.

Before becoming Brenda’s best friend, I had been busy effacing my personality as effectively as possible. Adoration for “Star Trek: The Next Generation”? Gone. Mathlete skills? My real loves were Tori Amos, complex algebraic equations, playing Chopin on the piano, and books, always books. In smalltown Idaho, those things were anti-cool. Friend repellents. And I learned early on that I had two options: tuck them away or suffer. I tucked them away and still suffered, but Brenda gave meaning and structure to that suffering. Or, at the very least, identity.

The night Brenda told me she’d lost her virginity — to a red-faced, forceful guy who dipped Copenhagen — she also told me he hadn’t used a condom. We cried in the school bathroom during her volleyball banquet. We cried again, two weeks later, when she told me that she’d gotten her period. With all my emotional energy vested in her, her worry and relief were my own. My own, non-Brenda life dwindled to nothing. She wore all of my clothes.

The guys got sketchier. One had a pager and belonged in The Outsiders. The one time I went with her to sneak out, we went in the hot tub of some super-senior, and I woke up the next morning with welts all along my swimsuit line — evidence of a bacteria commonly referred to as “hot tub disease.” I was mortified. Sin literally visited upon the flesh. Her mom knew nothing and everything.

In the end, there was never any epiphany. There was no overdose, even as some small and sad part of me began to realize that she was doing things I didn’t know about and not telling me. She knew I was her mirror — the one thing that reflected herself back to her.

Another best friend came along, equally charismatic, but without the sheen of manipulation that typifies teenage girls. She didn’t have a pool but she also didn’t need me as wordlessly and desperately as Brenda did.

By the end of the year, Brenda and I were ghosts to one another. She still wore several articles of my clothing. I had silently ceded them to her. Her family moved away and another Mormon family took over the ranch, excising its Land Cruiser skeletons. The words “Bad News Brenda” became shorthand for a certain period in my history.

I saw her, once, on a trip back from college, at some horrible hometown bar. She told me I looked amazing. The truth was that she did too. She had had a kid but it was clear that her body was still that of a 15-year-old girl: her eye make-up was too dark but the smile was the same. I wanted to take her out of there, get our bikinis, and go drink slurpies by the pool.

Every girl needs a toxic friend at some point in her life. Most people end up hating theirs, but I never felt hate towards Brenda. More like sand slipping through my fingers. I just hope she can still drive the stick shift the way I remember.

Anne Helen Petersen writes Scandals of Classic Hollywood when she’s not thinking about Idaho. Photo by janfredrikf.

Parks Commissioner Makes Like A Tree

“Adrian Benepe, New York City’s longtime parks commissioner, is stepping down after a decade in which he led a major expansion of the city’s parks system.” I know at least one person who is going to be very sad about this news.

Richard Ford's Freezer

Well, I started writing the book 20 years ago. I wrote 20 pages and then I set it aside. I am sort of a comer-backer, anyway. But I took this bag of notes and put it in the freezer compartment of my refrigerator. The story was already called Canada and I knew it was about a 16-year-old boy going across the Canadian border to Saskatchewan. I didn’t know why he was going there. I didn’t know why two parents would have abandoned him, but over those 20 years I would get a little idea about how a person would get in that situation, and write it down and add it to the envelope of notes in the freezer.

This Summer: Slushies for Kidults

Kidult summer trends! Unrelated but intriguing. First, all the new mens’ suits are shiny all of a sudden — made of wool and silk, shiny is the new, uh, not shiny. So buy some shiny suits that will be wildly out of vogue in two years. Second, it’s the summer of the “sophisticated slushie.” Which, you’ll be wanting one come Wednesday. You can blame Pok Pok for a lot of things — for being the most impossible no-reservations place in Brooklyn to actually eat at, for starters. (Today’s New Yorker calls it “dining as sport” and “an exhausting game.”) You can also blame them for the beer slushie: their “old-school, low-tech formula relies on a rotating barrel filled with a slurry of ice and salt that’s hooked up to a windshield-wiper motor. Stick a bottle of Singha in for five minutes, fish it out, tap it hard to further crystallize the beer molecules, and presto: instant brain freeze.” Yup, just another sign of the Portlandification of Brooklyn (by way of Bangkok, this time). It could be a worse summer beverage trend — at least it’s not an appletini or like “artisanal bitters and tonic.”

The Most Underplayed Gold Record of All Time

by Luke Hopping

For most of human history, celestial inspiration has flowed one-way: downward from the heavens. Pythagoras developed a theory known as the “harmony of spheres,” which posited the mathematical equations dictating planets’ travels could be notated to create brilliant music. The birth of the modern space program in 1958 spawned a renewed interest in capturing the sounds of the cosmos. Outerspace became a common muse among musicians, inspiring some of pop’s most memorable anthems. A very abridged list includes Elton John’s “Rocket Man,” Jimi Hendrix’s “Third Stone From the Sun,” and pretty much anything by David Bowie that still gets rotation on classic rock stations. Other times, the guidance of the stars made for less memorable material. In 1967, Dot Records released Leonard Nimoy Presents Mr. Spock’s Music from Outer Space, a fourth-wall bending compilation that received some surprisingly positive reviews. By the time of Neil Armstrong’s legendary broadcast from the moon, outerspace had already spent the better part of a decade being distilled through Earthlings’ stereos.

In 1977, the relationship between Earth’s musicians and the rest of the universe finally evolved into a dialogue. That year, NASA launched the Voyager Golden Records, a catalogue of mankind’s greatest musical achievements, into deep space. Still high on the same optimism that had put their guy on the moon a couple years earlier, the folks at NASA thought it would be a neat idea to dispatch a sonic emissary to anyone out there listening.

Compiled by Carl Sagan (so you know it’s good), the disc carries a handful of classics from across several cultures, an endearingly naïve message from President Carter, a creepy, hour-long recording of the future Mrs. Sagan’s brainwaves, a selection of nature sounds and some multilingual pleasantries (just in case aliens speak Esperanto). Depending how you look at it, the Voyager Golden Records’ mission is either charmingly antiquated or eerily at home among a Gingrich administration’s day one priorities. But the records do contain some legitimately important music. Many of these songs should be a staple of everyone’s iTunes, even if they are the kinds of vanity tracks that typically have zero plays.

Here, for your listening pleasure, we have recreated the late, great Carl Sagan’s overview of humanity’s most indispensable experiments in sound. Tempting though it may be to merely revisit the Western classics, we strongly encourage you to explore the lesser-known material. There are some beautiful pieces floating out in space with only a few thousand YouTube views here at home to back them up. They need your support!

Brandenburg Concerto No. 2 in F — J.S. Bach (Germany)

Puspawarna — Mangkunegara IV (Indonesia)

Senegalese Percussion (Senegal)

Pygmy Girls Initiation Song (Zaire)

Morning Star and Devil Bird (Australia)

El Cascabel — Lorenzo Barcelata (Mexico)

Johnny B. Goode — Chuck Berry (United States)

In a 1978 SNL skit, Steve Martin predicted aliens’ response to the records would be four words: “Send More Chuck Berry.”

Men’s House Song (New Guinea)

Tsuru No Sugomori — Goro Yamaguchi (Japan)

Gavotte en rondeau No. 3 in E Major — J.S. Bach (Germany)

Queen of the Night aria No. 14 — Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (Austria)

Tchakrulo (Georgia/U.S.S.R.)

El Cóndor Pasa — Daniel Alomía Robles (Peru)

If you’re like us and thought the Simon & Garfunkel version was the original, that accent might come as a shock.

Melancholy Blues — Louis Armstrong (United States)

Mugam (Azerbaijan/U.S.S.R.)

Rite of Spring, Sacrificial Dance — Igor Stravinsky (Russia/U.S.S.R.)

The Well Tempered Clavier, Book 2, Prelude and Fugue No. 1 in C Major — J.S. Bach (Germany)

Fifth Symphony, First Movement — Ludwig van Beethoven (Germany)

Izlel je Delyo Hajdutin — Valya Balkanska (Bulgaria)

Navajo Night Chant (United States)

The Faerie Round — Anthony Holborne (United Kingdom)

Worth clicking through, if only for the bizarre CGI-on-woodcut accompaniment.

Melanesian Panpipes (Soloman Islands)

Sounds much less like this than anticipated.

Wedding Song (Peru)

Flowing Streams — Kuan P’ing Hu (China)

Jaat Kahan Ho — Kesarbai Kerkar (India)

Dark Was the Night, Cold Was the Ground — Blind Willie Johnson (United States)

Cavatina from the String Quartet No. 13, in B Flat, Opus 130 — Ludwig van Beethoven (Germany)

While music-lovers may relish the notion of some alien life form happening upon Earth’s Greatest Hits, Vol. 1, Mr. Sagan was motivated by a different purpose. Knowing full well the odds of another space-faring race actually encountering the Voyager Golden Records were near zilch, he decided to view the project more as a meditation than an excursion. In his own words, “the launching of this ‘bottle’ into the cosmic ‘ocean’ says something very hopeful about life on this planet.” In honor of Mr. Sagan’s memory, we’ve included a 28th track that he was unable to blast off into eternity due to some very temporal licensing issues here on Earth.

Here Comes the Sun — The Beatles (United Kingdom)

Paul McCartney Is 70

Sir James Paul McCartney is ageless, but he is also 70 today. “Penny Lane” has been stuck in my head for approximately 30 years or so, so thanks for that, Paul.

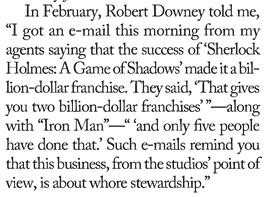

Robert Downey Jr. Explains Hollywood Stardom

This subscription-only profile of Ben Stiller has a substantial digression on Hollywood business and what currently constitutes a “star” (and who and who is not one). (Notably absent from assessment: Julia Roberts.) Stiller currently is one, by dint of having being the only actor with three billion-dollar franchises. And then there’s Robert Downey Jr.

Aaron Sorkin's Big Bomb

All we’ve heard about this show is that it’s absolutely terrible, and now? “’The Newsroom’ gets so bad so quickly that I found my jaw dropping.”

Oh God, the Weather Forecast, Oh God

Do you know what’s going to happen this week? That’s right. You’re going to burn alive. (Subscribe on iTunes.)

A Short History Of Book Reviewing's Long Decline

A Short History Of Book Reviewing’s Long Decline

by Jane Hu

There have been enough essays on the death of book reading, but have there been enough words devoted to discussing the decline of book reviewing? In the last decade or so — yes, indeed, as we’ve all wrestled with how the internet influences everything we do, including reading, writing, and writing about books (Tolstoy LOL tl;dr). But while the words “book-review” made its first print appearance as a headline in 1861 to just that — a review of a book titled How to Talk: A Pocket of Speaking, Conversation, and Debating (verdict: “The present work has the additional recommendation of an unmistakably useful subject, which is lucidly treated”) — the practice of criticizing the critics has always been with us. Most often, dissatisfaction with the state of book reviewing has come not from the readers who are the reviewers’ intended audience, but from writers who have felt their work mishandled, unjustly ignored, or cruelly misunderstood.

Launched in 1665, the Parisian Journal des Sçavans (“sçavans,” a word related to “savant,” and denominating a version of the French “scholar”) was the first publication devoted entirely to the task of criticism. Its aim was “to give readers (and scholars) a universal account of the state of learning,” with reviews “conceived of as installments of a continuous encyclopaedia to be carried on until the end of time.” The vision here was broad and expansive. In its pursuit of compiling scientific knowledge, Journal des Sçavans focused on objectivity; the reviews largely aimed to document findings, discoveries, and inventions in the world of biology and technology.

By the time of the first quote “book-review,” criticism had been in circulation for centuries — long enough for writers to know how it can sting. Understandably, then, the critic’s skepticism of an artist’s genius has invariably existed alongside the artist’s doubt over the critic’s judgment. It’s coincidence but seems fitting that shortly after the Journal des Sçavans launched, Alexander Pope was making such observations as:

Such shameless bards we have; and yet ’tis true

There are as mad abandon’d critics too.

The bookful blockhead ignorantly read,

With loads of learned lumber in his head,

With his own tongue still edifies his ears,

And always list’ning to himself appears.

(It’s fun to imagine what Pope would have made of James Franco, book critic, opening with the sally: “I read a lot.”)

Pope was not the first (or last) to register the observation that critics are philistines who only listen to themselves. Another common critique: that no one else listens to them. In 1847, Edgar Allen Poe reviewed several other reviewers of Nathaniel Hawthorne and found that:

These criticisms, however, seemed to have little effect on the popular taste — at least, if we are to form any idea of the popular taste by reference to its expression in the newspapers, or by the sale of the author’s book.

A few years following, Hawthorne appraised his own work in the 1851 preface to Twice-Told Tales. He noted that the book, then in its third edition, initially “failed, it is true — nor could it have been otherwise — in winning an extensive popularity.” He went on to speak of the dangers that too much positive criticism can hold for the writer — and the benefits of a book having received no public notices at all. (How sincere he was on this latter point, we can only conjecture. But writers who’ve had their books skipped over by the New York Times Book Review take note!)

Occasionally, however, when he deemed them entirely forgotten, a paragraph or an article, from a native or foreign critic, would gratify his instincts of authorship with unexpected praise; — too generous praise, indeed, and too little alloyed with censure, which, therefore, he learned the better to inflict himself. And, by-the-by, it is a very suspicious symptom of a deficiency of the popular element in a book, when it calls forth no harsh criticism. This has been particularly the fortune of the Twice-Told Tales. They made no enemies, and were so little known and talked about, that those who read, and chanced to like them, were apt to conceive the sort of kindness for the book, which a person naturally feels for a discovery of his own.

In a summer letter to Hawthorne, written around this time, Melville brings up another danger of criticism: the vast reduction of an artist to a brand.

I have seen and heard many flattering (in a publisher’s point of view) allusions to the “Seven Gables.” And I have seen “Tales,” and “A New Volume” announced, by N. H. So upon the whole, I say to myself, this N. H. is in the ascendant. My dear Sir, they begin to patronize. All Fame is patronage. Let me be infamous: there is no patronage in that. What “reputation” H. M. has is horrible. Think of it! To go down to posterity is bad enough, any way; but to go down as a “man who lived among the cannibals”!

Melville places “reputation” in scare quotes and distances himself from “a publisher’s point of view.” The fear that one’s name will endure as the wrong kind — represented and simplified to signify in the wrong ways — speaks to the artist’s anxiety of selling out. (Don’t worry, Melville. You good. Just look at Clarel. Defs not selling out.)

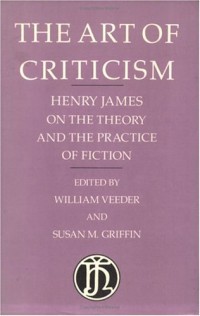

In a characteristically sassy letter to Howard Sturgis, Henry James registers his distance from reviewers as well:

I greatly applaud the tact with which you tell me that scarce a human being will understand a word, or an intention, or an artistic element or glimmer of any sort, of my book. I tell myself — and the “reviews” tell me — such truths in much cruder fashion. But it’s an old, old story — and if I “minded” now as much as I once did, I should be well beneath the sod. (May 1899)

We can all be grateful James never minded — and made less and less sense (cf Golden Bowl) — especially as he neared the sod.

***

In December 1900, a “Veteran Book Reviewer,” otherwise anonymous, wrote a commentary titled “Up-to-Date Book Reviewing” for The Independent:

The decline of the book review is first of all due, as Mr. Halsey said in his interesting but too discursive paper in The Independent, to the fact that there are too many books to review.

Mo books, mo anonymous veteran book reviewers.

Not long after, American journalist Paul Elmore More was contending that writers might sometimes actually thrive on criticism: “When I did most of my work there was almost a critical vacuum in this country and in England… It was something of an achievement — I say it unblushingly — just to keep going in such a desert.”

But more criticism doesn’t necessarily equate to generous and varied discussion. Writing in 1917, H. L. Mencken lobbed this critique at phonies:

When I began to practice as a critic, in 1908, there was still plenty of excuse for putting it on. It was a time of almost inconceivable complacency and conformity. Hamilton Wright Mabie was still alive and still taken seriously, and all the young pedagogues who aspired to the critical gown imitated him in his watchful stupidity.

Nothing like a deluge to make one long for the desert. In 1928, Edmund Wilson wrote in “The Critic Who Does Not Exist”: “It is astonishing to observe, in America, in spite of our floods of literary journalism, to what extent the literary atmosphere is a non-conductor of criticism.”

***

Why do so many book reviews exist? In part to keep the book reviewer fed, as the following modernists would suggest:

• Virginia Woolf (1939): “He has to review; for he has to live; and he has to live, since most reviewers come of the educated class, according to the standards of that class. Thus he has to write often, and he has to write much. There is, it seems, only one alleviation of the horror, that he enjoys telling authors why he likes or dislikes their books. “

• George Orwell (1946): “In much more than nine cases out of ten the only objectively truthful criticism would be ‘This book is worthless’, while the truth about the reviewer’s own reaction would probably be “This book does not interest me in any way, and I would not write about it unless I were paid to.”

• Cyril Connolly (1948): “[R]eviewing is a whole-time job with a half-time salary, a job in which the best in him is generally expended on the mediocre in others.”

But the most quoted rejection of the book review as such might be Elizabeth Hardwick’s “The Decline of Book Reviewing,” which appeared in Harper’s in 1959, and the wisdom of which still holds today:

In America, now… a genius may indeed go to his grave unread, but he will hardly have gone to it unpraised. Sweet, bland commendations fall everywhere upon the scene; a universal, if somewhat lobotomized, accommodation reigns. Everyone is found to have “filled a need,” and is to be “thanked” for something and to be excused for “minor faults in an otherwise excellent work.”

Fast forward nearly three decades and you have Harold Bloom arguing Hardwick’s point, just from the other side: “Instead of a reader who reads lovingly, with a kind of disinterest, you get tendentious reading, politicized reading.”

Enter Jonathan Franzen (Canon Preacher, Part II) in his “Perchance to dream” essay, published by Harper’s in 1996, five years before Oprah invited him to sit on her couch:

The media’s obsessive interest in my youthfulness surprised me. So did the money. Boosted by the optimism of publishers who imagined that an essentially dark, contrarian entertainment might somehow sell a zillion copies, I made enough to fund the writing of my next book. But the biggest surprise — the true measure of how little I’d heeded my own warning in The Twenty-Seventh City — was the failure of my culturally engaged novel to engage with the culture. I’d intended to provoke; what I got instead was sixty reviews in a vacuum.

Instead of taking up Hardwick’s rejection of banal commentary, or even Bloom’s urge to follow the text lovingly, Franzen made book reviewing (media in tow) about what truly matters today: himself. (At least he hadn’t been called “the man who lived among the cannibals.”) Interesting also to hear in his use of “vacuum” an echo, as if caught in a circling reverb, of Paul Elmore More’s decades-before lament on the poor state of American criticism.

***

As we approached 2000, with newspapers shrinking and the Internet swelling, reports on the state of book reviewing become markedly bleak. I would call these pieces Manifestos, if they weren’t so despondent in tone. In “The Amazing Disappearing Book Review Section,” a 2001 piece for Salon, Kevin Berger examined the San Francisco Chronicle’s decision to do away with its pullout, 12-page book section (while also moving book reviews to the back of its Sunday entertainment section), finding it illustrative of a wider move to replace book criticism with other forms of pop culture observation. A dour mood is struck at the beginning of the piece when one of the paper’s editors, leading Berger to the department, admits, “I’ve actually never been down there.” The department’s out-of-sight, out-of-mind location mirrored its exile to the newspaper’s back pages: “A sign on a far wall said ‘Book Review,’ followed by an arrow.” At this millennial mark, entering the realm of book reviewing had become akin to placing yourself in a horror film.

The reduced status of printed book reviews was spurred, at least in part, by the increase of online discussions, which brought with them their own type of horror: snark. In 2003, Heidi Julavits lent a determinedly upbeat response in the inaugural issue of The Believer (the name of the magazine signaling its own ardency) in the essay “Rejoice! Believe! Be Strong and Read Hard!”: “The upshot, however, is this: snark is a reflexive disorder, whether those who employ it realize it or not; the pointlessness of fiction only comes back to suggest the pointlessness of its commentator.”

If your commentators only feed you snark, then what is there left for fiction writers to chew on? The point wasn’t to divide online from paper, but to see them as mutually benefiting (or else dismantling) one another. As Michael Connelly noted in the L.A. Times in 2007: “People who read books also read newspapers.” People who read books or newspapers, ultimately, read.

Around this time, Richard Price, writing at Critical Mass, offered his own assessment of how the new environment was shifting criticism: “I think our crisis is instant evaluation versus expansive engagement, real time versus reflective time, commodity versus community, product versus process. Substituting a user’s rating for a reader’s rearrangement threatens to turn literature into a lawn ornament.” (A few months later, Nan Talese said: “I think the best book reviews are the ones in People magazine and Entertainment Weekly.”)

“Who Killed the Literary Critic?” was the subject of a 2008 Salon conversation between critics Laura Miller and Louis Bayard. The trigger for the discussion: a book called The Death of the Critic which hypothesized that the lack of both public intellectuals and a rigorous academic community of inquiry had caused criticism to founder. Miller considered how the increase of “too many other entertainment options” takes away from reading time. Against this, both Miller and Bayard discuss the “fuck you” aspect of modernism’s output as a factor that might drive readers to kindlier, more benevolent texts — novels and television shows that don’t wish to frighten audiences with their aggressive difficulty. “There are no critical movements evident today,” observed Miller. (And even if there were, they’re not all going to be online, or in one forum. Any real critical movement simply should not be confined to one community or some new means of communication.) Perhaps a large problem in the decline of good criticism is that readers no longer know how, or where, to find critics, and, more importantly, how to define what makes it Good.

Writing for the New Yorker in 2008 about the Sam Zell-mandated cutbacks at the L.A. Times Book Review, Dana Goodyear quoted a friend as saying: “Can you imagine if this were happening at the New York Times?” When the Washington Post published its last edition of Book World the next year, Dick Meyer mourned it as an “injury to our collective literacy,” adding that, “If that sounds snobbish, well, so be it.” Books, he opined, reign on the media chain of “columns, blogs, TV shows, magazine articles and Twitter tweets.” Sam Tannenhaus struck a similar gloomy note in an interview with the Oxford American: “It’s a concern, not only for authors and readers but also for reviewers, who practice an art whose cultural status seems to be going the way of the German mark during the Weimar Period.”

As large cultural movements occur, book review culture can’t help but be influenced. In an Atlantic essay, Lorin Stein, after making due note of Sept. 11, rightly, refers to the ways in which online discourse has forced book reviewing to change its terms. Amazon and Google are killing the book, are killing the newspaper, are killing the book review. If the Internet has allowed anything, it has allowed this argument to be replicated ad infinitum across it. And I’m looking and hoping for a story that at least begins to let us see where book criticism might go (and if it should go at all).

Elizabeth Gumport’s 2011 essay (and a true manifesto) “Against Reviews” for n+1 is an engaging start:

If we wouldn’t describe a book to someone we wanted to sleep with, we shouldn’t write about it. It is time to stop writing — and reading — reviews. The old faiths have passed away; the new age requires a new form.

Like Hardwick, Gumport’s piece will likely have some staying power. Maybe if our contemporary reviewers tried for the same kind of searching criticism these writers do, we’d be getting somewhere.

Who first screamed death of the book review? Did they really even know what a book review was, is and could be?

Related: What Makes A Great Critic?

Jane Hu judges a book review by its title. “Making death mask” photo courtesy of Obit.