And That Is How You Do A Disclosure

“Full disclosure: Anson Burlingame, who served under Seward as U.S. minister to China, was this reviewer’s great-grandfather’s cousin.”

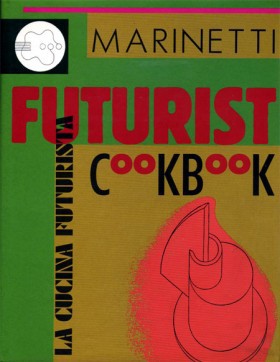

Chicken With Ball Bearings: How To Cook Like A Futurist

Chicken With Ball Bearings: How To Cook Like A Futurist

by Willy Blackmore

After years of disavowing the unwanted, unloved phrase “molecular gastronomy,” the culinary avant-garde was gifted in 2010 with a new umbrella term under which to gather: Modernist cuisine. The name came from Nathan Myhrvold, whose five-volume doorstop of a cookbook of the same title offers both a history of culinary thought and detailed descriptions of the techniques and recipes pioneered by the likes of Ferran Adrià and Heston Blumenthal. (A shorter version is due out in October.)

Before diving into the proverbial immersion circulator, Myhrvold turns to art history to make the case for the title Modernist Cuisine. Writing on the artistic advancements of the Impressionists, Myhrvold expresses admiration for the group’s determination to do away with tradition in pursuit of an art that more accurately reflected modern life. But Myhrvold is less approving when it comes to the artists’ eating habits. He contends that the diets of the “cultural revolutionaries who launched these movements,” the Impressionists and the other Modernists that followed them, were unfitting of their artistic character, consisting only of “very conventional food.” After stating, incorrectly, that Modernism “never touched on cuisine,” Myhrvold goes on to claim that his cohort is doing what he believes the avant-garde of the 20th century failed to: Extend Modernism to the culinary realm.

The former Microsoft executive has clearly not devoted enough time to his art-history reading. It’s difficult to believe that he never bumped into the imposing figure of Filippo Tommaso Marinetti, founder of the Futurists, Italy’s aggressively right-wing art movement that worshipped technology as well as war.

The Futurists made paintings, sculpture, poetry and music — and they tackled the culinary world as well. In 1932, Marinetti published The Futurist Cookbook, an extended manifesto that railed against technologically antiquated kitchens, International-style cuisine and, above all else, pasta, a food Marinetti hoped to abolish from the Italian diet. In Futurist thinking, the empty calories of spaghetti were an impediment to a quick-moving modern life, the collective dead weight of so many plates of pasta sitting in the nation’s stomach holding Italy back from advancing into the brave new technological world. At Futurist-friendly restaurants, Marinetti suggested that the waiters would tell patrons that “we have come to this decision [to ban pasta] because pasta is made of long silent archeological worms which, like their brothers living in the dungeons of history, weigh down the stomach make it ill render it useless. You mustn’t introduce these white worms into the body unless you want to make it as closed dark and immobile as a museum.”

Marinetti proposed a complete rewriting of Italian food traditions, a new cuisine influenced by science and unencumbered by tradition — culinary Modernism, by another name, an approach to cooking that has Ezra Pound’s command to “make it new” at its mechanized heart. Marinetti wrote that the new cuisine, “tuned to high speeds like the motor of a hydroplane, will seem to some trembling traditionalists both mad and dangerous.”

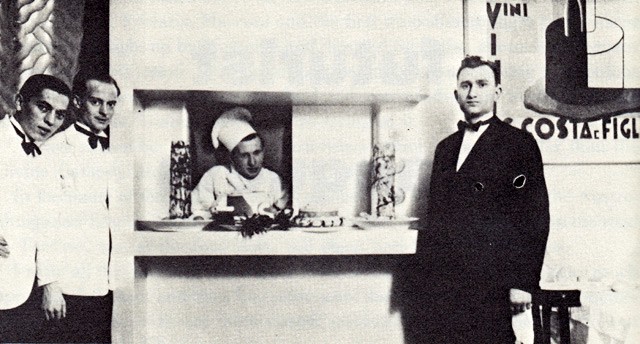

At the Holy Palate restaurant in Turin.

Out of the kitchen went quiet, hearthside domesticity. In came the Machines. The Futurist kitchen Marinetti envisioned was an extension of his proto-bro obsessions with cars and guns and airplanes. Countertops would be lined with ozonizers, ultra-violet ray lamps, electrolyzers and colloidal mills, the cutting board jockeying for space with centrifugal autoclaves and dialyzers. The electrolyzer would be employed “to decompose juices and extracts, etc. in such a way as to obtain from a known product a new product with new properties.” All of this decades before Pacojets and immersion circulators and iSi siphons would become fetish objects of the kitchen. Marinetti’s kitchen, more a vision than a reality, was really a list of possibilities rather than detailed uses. The technology could be employed to improve nourishment (Marinetti was obsessed with nutrition and, along with his anti-pasta vitriol, rails in the cookbook against processed grains, eating too much meat, and robbing vegetables of their healthfulness by overcooking) or to perfectly balance acidity and alkalinity, salt and heat. Less practical electric dreams include Marinetti’s desire to make foods taste and smell of ozone, or to run drugs through that colloidal mill.

Marinetti surely would have approved the technological approach to cooking promoted in Modernist Cuisine, but in terms of breaking with the status quo, of making it new, Myhrvold’s cookbook has little to offer. His rebellion has more to do with better-living-through-technology takes on familiar, traditional dishes such as burgers or pad Thai; deconstruction and nostalgia, those well-established tropes of postmodernism, play a significant role. Sit it next to the unhinged inventiveness on display in The Futurist Cookbook, and I find myself preferring the company of the crew of warmongering Fascists.

But what about the food? There are actual recipes in the book, buried in the final pages under the title “Futurist Formulas for Restaurants and Quisibeve.” You can learn to cook Futurist Risotto with Cape Gooseberries or The Soil of Pozzuoli and the Greenery of Verona, which involves chewing candied citrons stuffed with fried cuttlefish “as if they were anti-Futurist critics.” But Marinetti devotes far more of his writing to recounting Futurist banquets and dinners at The Holy Palate Restaurant in Turin, where his culinary ideology was put into practice. The centerpiece of most of these meals was Sculpted Meat, a tower of veal stuffed with vegetables, honey dripping Karen Finley-like down its side, toward the base of sausages and “three golden spheres of chicken meat.” Envisioned by the painter Fillìa as a “symbolic representation of all the varied landscapes of Italy,” this veal tower is repeatedly referred to by Marinetti as the cornerstone of Futurist cooking.

A Futurist banquet in Tunis. Marinetti is standing in front.

Tactile and scent components accompanied other dishes, an encouragement to diners to use all of their senses. In one such dish, a salad of fennel, olives and candied fruit is accompanied by a small rectangle containing various textured materials. While eating the foods, the diner “delicately passes the tips of the index and middle fingers of his left hand … a swatch of red damask, a little square of black velvet and a tiny piece of sandpaper.” Sound and a heightened level of scent are introduced into the experience too: “From some carefully hidden melodious source comes the sound of part of a Wagnerian opera, and, simultaneously, the nimblest and most graceful of the waiters sprays the air with perfume.” Another dish, Chickenfiat, featured the very taste of industry itself: Steel. The flavor is delivered by a handful of ball bearings tucked into the bird’s shoulder, a simple act of seasoning that turns this dish into the ideal synthesis of Futurist ideas about advancement in technology (the more, the bigger, the better) and the development of culinary arts that “eschews plagiarism and demands creative originality.”

Politics and pasta fall away in the “Definitive Futurist Dinners” section of the book, which consists of short prose-poem-like “recipes” for different meals. Reading more like Yoko Ono’s instructional paintings than Julia Child, these “definite Futurist dinners” are more artistic in terms of the prose itself, and largely devoid of Marinetti’s grandiose manifesto tone.

One that cuts close to the heart of the Futurist ideal — the perfect union of life and art and technology — takes place in the cockpit of an Autostabilizing DeBaernardi airplane flying 1000 meters above the Italian countryside. Within those curved steel walls, decorated with Futurist “aeropaintings,” lobsters are prepared. After being boiled, “electrically,” in seawater, the meat is removed and the shells, tinted blue with methylene, are stuffed with a “pulp of egg yolk, carrots, thyme, garlic, lemon rind, the eggs and liver of the lobsters, capers” and sprinkled with curry powder. But rather than eating the shellfish, “the diners, holding in their fists little ceramic bell-towers full of Barolo mixed with Asti Spumante, eat villages, farms and fields speeding by.”

How could similarly seasoned lobster, cooked sous-vide, ever compare?

Willy Blackmore is the Los Angeles editor of Tasting Table. He is not a Fascist.

Let's Occupy Wall Street

I hope that, if you are interested and available, you’ll join me and many others at the Occupy Wall Street one-year anniversary demonstrations. They begin tomorrow.

I don’t have every goal — or method — in common with other protesters. Heck, I don’t even support a “Robin Hood tax” on financial transactions. Also, I am too bourgeois and busy to be arrested for civil disobedience. But I do believe, along with many Occupy folks, that in many ways the institutions of our country unfairly favor the rich, and that many institutions unfairly conspire to keep poor people poor and uneducated — and to make working people ever more disposable and insecure. If I have to pick a side, and it rather seems like I do, then I’ll be on the side of the “ecoterrorists” and “hippies” and the “anarchists” and the — gasp! — “union members.” Sometimes, we’re indistinguishable.

And lots will happen at 7 a.m. Monday morning at Wall Street. (Um, should be pretty quiet overall, anyway, given that it’s Rosh Hashanah, so, that’s weird, but.) The vast majority of us in attendance — as always — will be polite, friendly and principled. If, as a group, we are somewhat incoherent, that is absolutely fine.

Two Poems By Brenda Shaughnessy

by Mark Bibbins, Editor

This Person-sized Sky with Bruise,

simultaneously orange and violet,

(though my eyes are closed) is

either my inner color (that covered mirror)

or simply dusk.

An opaline sheet

pulled because the night is ashamed

to come in front of everyone,

blacking out in joy.

Too shy to spill its milk on the stained

tablecloth of strangers

like I have. When it’s finally dark

outside, it’s finally

loose inside and the doubleness

of things seems too true to be good:

my way and the highway.

Night. It has two hands

I can use. Its fingers in a plum

too ripe not to split.

I had to split it. It was so much

itself — bloody flesh,

wild purple skin. A fistful

so lush it was almost imaginary,

smelling of love, it didn’t matter whose.

The Seven Deadly Sins of (and Necessary Steps Toward) Making Art

Pure art is, in a sense, pure innocence.

But artists are, in themselves, putrid with paradox.

The following seven sins/steps should help the wretched

to remember: the pitfalls are the progress!

1. Deadlines

Aka Avalanche Everlasting,

Opportunity Oppression.

“You will miss me then I’m gone….”

All at once a million kinds of calendar.

2. Motivation

Ask yourself: What is my longing?

Answer yourself: I long for the world, in the form

of a person, which is me,

in the form of a new world,

in the form of a new person,

which is the new me, in the form…

ad infinitum.

3. Goals

Stop staring out that old woman’s window like a cat.

4. Distinguishing between “Saying” and “Doing”

“Everyone dies.”

is different than

“Everyone died.”

5. Self-Absorption

This inner spinning, that petty city

the mind built,

robs the psalm of its robe of calm,

my naked voice thin and shrill in the wind.

6. Delusions of Grandeur

I’m such a fraud,

I can’t even convince you

of my fraudulence.

7. Everyday Magic!

The new burn on my knuckle,

white, shiny, raised:

our dinner’s afterlife, lingering ghost.

Brenda Shaughnessy is an Assistant Professor at Rutgers-Newark. Her third collection, Our Andromeda, is just out from Copper Canyon Press.

Soon it will be autumn. Your life, however imperceptibly, will change. The best way to cope with that is through the consolation of poetry. Fortunately for you, and the person you will become this fall, we’ve got a big ol’ mess of poetry right here for you.You may contact the editor at poems@theawl.com.

"Felicity" And The Joys Of Decent TV

“Felicity” And The Joys Of Decent TV

by Ben Dolnick

Without quite meaning to, I spent a good deal of this TV off-season watching a show in which I had no interest whatsoever when it was actually on the air. Thanks to the miracle of Netflix Instant and a slight compulsive streak, I watched all four seasons of “Felicity” this summer — that’s 84 episodes, 63 hours. Every breakup and reconciliation, every Christmas break and dorm-room confrontation. This sounds, as I type it out, like a bizarre thing to have done. Neither intriguingly campy (my summer of watching soap operas) nor admirably highbrow (my summer of watching the entire AFI greatest films list). Just sort of… there. Like a summer of eating spaghetti with Prego tomato sauce.

However: I’m convinced (and not just, I don’t think, to retroactively justify all those hours) that this was a good use of my time — and even that you should, if you happen to find yourself with a months-wide gap in your entertainment calendar, consider doing the same. Allow me to explain.

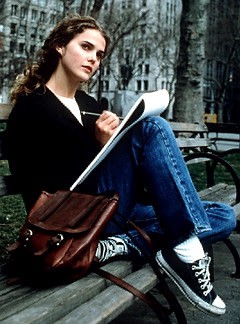

First, and maybe least importantly, “Felicity” turns out to be a surprisingly decent show — intermittently moving, reliably involving, more self-aware than it’s usually given credit for. To the extent that it has a premise, it’s that a pretty, young woman named Felicity Porter (played with career-imprisoning memorable-ness by Keri Russell) goes to college in New York City and grows up.

It’s of that genre of shows with predominantly white casts — also included here is “Brothers and Sisters” and “Parenthood” — that I’ve come to think of as “pink noise.” Meaning: there is, at one level, a great deal of drama, crisscrossing currents of love and betrayal, crisis and resolution, but that if you take even the slightest of steps back — if your attention wanders even for long enough to think about what you’ll have for dinner tomorrow — the entire thing dissolves into a blur of attractive white people making problems out of nothing. It’s compelling and embarrassing in more or less equal measure.

The more important reason I’m glad to have gone on my “Felicity”-bender, though, has less to do with the show itself than it does with a cultural conservationist streak I’ve been surprised to discover in myself. I would, in a way, be just as glad to have watched “Murder, She Wrote,” or “The Real World: Season 1,” or “Ally McBeal,” and perhaps next summer I will.

There’s a strange convention, in both the consuming of culture and the writing about it, to pay attention only to that which is new and that which is classic. It’s either the absolute present (see Slate’s Talmudically reverential weekly discussions of “Louie) or that which is firmly in the canon (see Dave Kehr’s very good weekly column about which decades-old movie is now being restored to Blu-ray). This is the underlying logic of the two types of cultural lists that appear throughout each year as reliably as holidays: 11 books we can’t wait for this fall! The 10 greatest heist movies ever made!

The art that has the misfortune to be neither brand new nor brilliant — which is to say, the vast majority of all art ever created — is relegated to an enormous coastal reef of forgettability. The three seasons (!) of “Parker Lewis Can’t Lose.” Arthur Conan Doyle stories about Brigadier Gerard. The John Hughes movies that didn’t make it into career retrospectives. Countless hours of work, millions of pounds of film equipment and carefully revised drafts and audition tapes, forgotten on the ocean floor like so many old subway cars.

Now, most of the stuff in this cultural reef — like most of all stuff — deserves to be forgotten. “Saved by the Bell: The College Years”; all novels based on movies, (except, strangely, 2001: A Space Odyssey); Michael Jackson’s Invincible. These things can, for all I care, remain entombed until the explosion of the sun.

The things that I take pleasure in exhuming are the works of reasonable quality, created in at least relatively good faith. I’m talking about the books and movies and shows that did their job — causing some number of minutes of your life to pass with a minimum of fuss — with a certain soldierly sense of responsibility. Someone once took care to construct a plausible plot by which the character of Ben Covington could make the turn from an aimless slacker to an aspiring doctor. Some group of (deeply misguided) people once sat around a table and decided that, beginning with season three, “Felicity” needed a a new theme song and credit sequence. This care, this effort poured into something so soon forgotten, is oddly moving to me, in the way that watching monks work on a sand mandala is moving.

Our ordinary treatment of reef-material, after all, is maddeningly sketchy and reductive. The 109 episodes of Ellen Degeneres’ sitcom have decomposed entirely except for the fact of Ellen kissing a woman. “Murphy Brown” — all 247 episodes of it — survives as nothing more than something about Dan Quayle and single motherhood. And “Felicity” — the many hours of parallel plotting, the court-of-Versailles-ish loyalties and rivalries — has been reduced to no more than a haircut. Years of peoples’ lives have been compressed into a thing to say when you walk past someone curly-haired going into a barbershop.

But it isn’t out of respect for J.J. Abrams (who has, after all, done fine for himself) that I’m glad to have rehydrated the essence of “Felicity.” There’s a pleasure, and even a certain mental importance, in periodically reminding oneself that the past — personal, cultural, and planetary — was as finely grained as the present. It’s an exercise not unlike reading one’s own old journals. You might think, casually, that you have a fairly good handle on what your life was like in, say, 2002 — that job, that apartment, that relationship. But you discover, upon actually wading into the line-by-line dailiness of it, that you’d forgotten entire plot arcs, characters, preoccupations that at the time seemed of vital importance. There’s so much missing texture in one’s feeble notions of the past. The years were made of months which were made of weeks which were made of days which were made of hours. The dinosaurs spent much more time scratching themselves and turning over in the sun than they did posing like the skeletons in the Natural History Museum. And “Felicity,” it turns out, contains a lot more than a haircut.

To re-experience “Felicity” in its entirety is to wander through a kind of living museum of turn-of-the-millenium-Manhattan — look how people still used pay-phones! look at those carpenter jeans! look at Keenan Thompson and John Ritter and Tyra Banks! Watching the show occasionally gave me a feeling like Emily in Our Town: “Do any human beings ever realize life while they live it? — every, every minute?” I found myself feeling an odd affection for the actors, the writers, even the original viewers — all collaborating on this snowman at the end of winter.

So: in between reacquainting yourself with the gang from “Happy Endings” and finally finishing off The Dekalog, make a little time this fall for “The Wonder Years,” or Uncle Buck, or even “Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles.” Your options are endless: even at this late, post-Quikster date, the offerings on Netflix Instant resemble nothing so much as a delightfully bizarre shelf of VHS’s you might find in the TV cabinet of a beach-house. You might not be able to keep up with your colleagues’ conversation about “Boardwalk Empire,” and you might not have an opinion about the novel that’s suddenly in every bookstore window. But you will, in squandering a bit of the present, have regained even more of the past. Like Felicity herself in one of Season Four’s more regrettable developments (and here I offer an embarrassed, decade-belated spoiler alert), you’ll have learned to time-travel.

Ben Dolnick is the author, most recently, of Shelf-Love, a Kindle Single about Alice Munro.

New York, September 13, 2012

★★★★ A realist take on the season. The sky had accumulated some grubby tan around its lower edge, and the breeze through the window brought in mild notes of mud and fuel oil and aquatic life. The Hudson was not a visual element but a river, two crosstown blocks away. See it, smell it. This made the breeze more comforting, if anything. Out on the sidewalk was crowded and almost hot. Stroller wheels caught stroller wheels. Ice carts and an organic soft-serve ice cream cone truck offered palliatives. After sundown, the laughter of children made its way in the window. Also, at some point, a large housefly.

Dead Can Dance, "Opium"

Here’s the new one from Dead Can Dance. Brendan Perry sounds more like Leonard Cohen every year.

The First Video That Meant Something To Me: The Birthday Party's "Nick the Stripper"

The First Video That Meant Something To Me: The Birthday Party’s “Nick the Stripper”

by John Darnielle

Part of a series for the new Awl Music app.

MTV didn’t come to southern California when it came to the rest of the country, because southern California got cable television later than everybody else. I forget exactly why this was, but there’s a story to it: something about networks not liking cable, I think, and being able to flex their muscles a little harder in their natural environment. I’m not sure exactly. Like most southern California kids, anyway, I first encountered music video on shows that resembled American Bandstand. DJs from local radio would host a room full of dancers while videos played.

My friends and I were snobs, and we basically did an annoying-theater-kid version of Beavis & Butthead with these shows every damn day. Spotting the Lou Reed bite in the last bridge of “I Melt With You.” Soaking up the pre-Prince Charming Adam & the Ants videos. Wondering what anybody saw in Translator. Although it would be fair to say we liked music videos more than we admitted, none of them really meant anything to us; the bands we liked didn’t make videos that we got to see. There were rumors of Cabaret Voltaire videos, and whole VHS copies of A Factory Outing at prohibitive prices behind the counter of the record store, but there was no way to see them: they were strictly for-sale items. Even once southern California got MTV, they weren’t showing the stuff we were curious about.

But then I turned sixteen and drew a paycheck or two and I got my hands somehow on the Pleasure Heads Must Burn video. Maybe Joel bought it, I don’t know. It was a live Birthday Party show. They’d broken up before we’d gotten hip to them, so we’d missed their only L.A. show; a damning review of it in the L.A. Times had made me curious about the band, and I’d bought a cut-out copy of Junkyard, and that record changed my life. Nick Cave released his first solo album shortly after we’d gotten into his old band, and we all drove out to Pasadena to see him live, and I got major religion about it; and our collective what-we-missed Birthday Party obsession grew with each hard-gotten piece of the back catalogue until finally we got around to seeing the video for “Nick the Stripper,” from the Prayers on Fire LP.

There is little bleaker in the history of rock video than “Nick the Stripper.” Young Australian men with wild hair held firm by drying egg whites mill about a night near a fire where pigs’ heads on sticks are hoisted high. Black paintings of spidery skulls glow and pulse, red and white. The band plays in a tent. Nick Cave is shirtless and has painted the word “HELL” on his chest. The band saunters out to join the broader, burning party: people carry empty birdcages or wear masks. The fire spreads to a nearby river. The atmosphere is anti-Bacchanalian: crowds of people revel in the void of degradation. There is a guy hanging from a cross. Cave sings to a goat that seems destined for sacrifice on a nearby spit. Tracy Pew, may he rest in peace, keeps his cowboy hat on.

I want to say “my friends and I were dicks,” but it’s wrong to speak on behalf of those who aren’t here to defend themselves, so let me just say that I was kind of a dick back then. Anything that looked like good plain fun was for squares, as far as I was concerned, and music video was largely an evangelical pulpit for uncomplicated good times. As far as uncomplicated good times went, I was against ’em. I would eventually grow out of this attitude. But joyless dicks need love, too, and for 16-year-old me, the “Nick the Stripper” video was a vindication. There were people elsewhere in the world who wanted to paint as dire a vision as possible and record it somehow so that somewhere along the line it might cross paths with similarly dour-minded people. There were people who liked dark things and only dark things. There was somebody besides me who thought painting some scary-ass word on your body was a bad-ass thing to do. It wasn’t everything, learning this. But it was something. It was enough.

John Darnielle is the singer from the Mountain Goats. He believes chopped salads will shortly make a comeback of truly historical proportions.