Soundscan Surprises 4/6

Back-catalog sales numbers of note from Nielsen SoundScan.

The definition of “back catalog” is: “at least 18 months old, have fallen below №100 on the Billboard 200 and do not have an active single on our radio.”

Fleetwood Mac’s last recorded album together turns 30 tomorrow. Country star Sam Hunt is enjoying that they call a “crossover hit” with a song called, um, “Body Like A Back Road” (driving with my eyes closed, I know every curve like the back of my hand).

The death metal band Death’s fourth studio album, Human, was reissued on the same day as the Doors deluxe reissue. Guess which one has sold more copies since then! I’m assuming Lana Del Rey is on the rise because she’s got an album on the way. Dr. Hook’s Greatest Hooks is a compilation album that was released in 2007, so that makes it ten years old.

2. FLEETWOOD MAC TANGO IN THE NIGHT 4,213 copies

4. HUNT*SAM MONTEVALLO 4,000 copies

28. DEATH HUMAN 1,915 copies

60. DOORS*THE THE DOORS (DELUXE EDITION) 1,531 copies

122. DEL REY*LANA BORN TO DIE 1,179 copies

199. DR. HOOK GREATEST HOOKS 934 copies

(Previously.)

On The Straße Where You Live

It’s a book about a street in Berlin, get it?

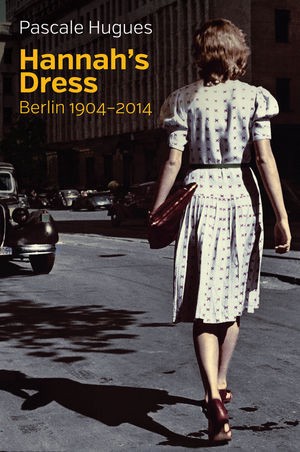

In 2016, for reasons completely coincidental to what wound up happening as the year reached its end, I read a bunch of books about Germany in the twentieth century. This is not to brag about my prescience or my deep curiosity about the events that shaped our world, but to get it out up front that I probably have a little more background information than the average reader coming to Hannah’s Dress: Berlin 1904–2014 might. I don’t necessarily think that not knowing a good bit about the architectural details of Berlin before and after the wars will detract from anyone’s enjoyment of the book, but I do want to tell you that I didn’t go in completely blind on this one, so I might have been more prone to appreciate it. Anyway, here’s the deal with the story:

Hannah’s Dress tells the dizzying story of Berlin’s modern history. Curious to learn more about the city she has lived in for over twenty years, journalist Pascale Hugues investigates the lives of the men, women and children who have occupied her ordinary street during the course of the last century. We see the street being built in 1904 and the arrival of the first families of businessmen, lawyers, and bankers. We feel the humiliation of defeat in 1918, the effects of economic crisis, and the rise of Hitler s Nazi party. We tremble alongside Hannah and the Jewish families who experience the pain of exile or the horror of deportation. And we experience the hardships and anguish of those who remain — forced to make agonising choices under the constant fear of Allied bombing raids. In 1945 the street is all but destroyed, the handful of residents left want to forget the past altogether and start afresh. When the Berlin Wall goes up, the street becomes part of West Berlin and assumes a rather suburban identity, a home for all kinds of petite bourgeoisie, insulated from the radical spirit of 1968. However, this quickly changes in the 1970s with the arrival of its most famous resident, superstar David Bowie. Today, the street is as tranquil and prosperous as in the early days, belying a century of eventful, tumultuous history.

The Bowie bit is a tad overdone, but that pretty much describes it. So: The idea of telling a story through the lives of the people on one street sounds a little gimmicky, and it is, but it also works pretty well here. The street itself, in the Schöneberg section of the city, sounds about as boring as any place adjacent to the front row of a century’s history could actually be, but what keeps the book interesting is Hugues’s conversations with its residents — most of whom who, in the first part of the book, happen to be Jews.

As an American of a certain age and a certain background I was raised with a steady diet of Holocaust as part of my history curriculum, so I found it striking how moved I was by some of the stories here of those who were taken away and those who came back. It is either an example of how individual cases can be more affecting than sheer statistics or a good reminder that you need a refresher course every decade or so on how horrible the events of that era actually were, hopefully one that we will continue to only get from works of analysis and not any kind of 21st century reenactment. The book loses steam as it heads toward the present but not in an unpleasant way — more like, “history recedes and normal life resumes.” Eventually it is just a street, as any other, except it is filled with German people, and you know how they are.

What else can I tell you? I am always dubious when people writing reviews refer to a book as “admirably translated,” as if they are native speakers of the original language and alert to the justeness of every mot, so I will say this one has a couple of issues with tense consistency but otherwise seems fine as far as I am aware. Okay? You should know by now if this is the sort of thing you would be into, and if you are I say go ahead. If you’d like a reading list of books about 20th century Germany to get you started please get in touch, but also maybe get a life.

The Germanest Form of Music Ever

Deutschland über us

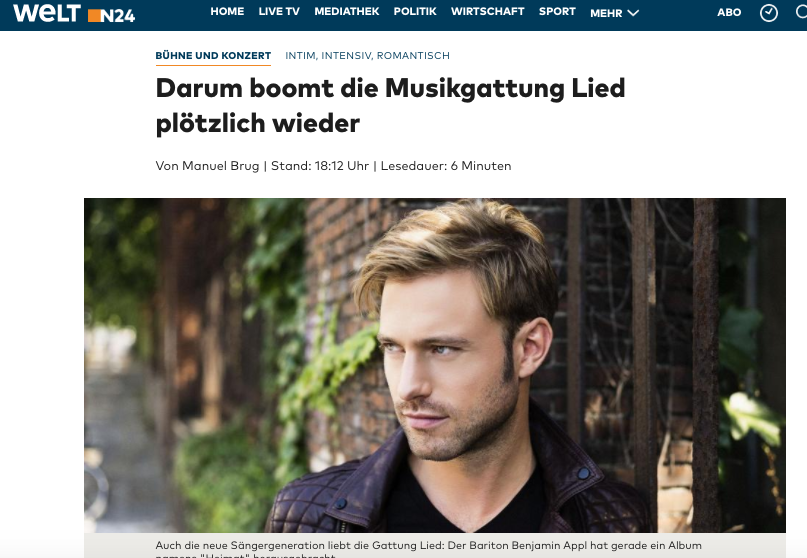

Meet Benjamin Appl. He’s a 35-year-old baritone with a jawline that I’d let slice me to bits and then thank for doing it — and the voice of an angel (provided that said angel had a very deep voice). His new album is taking the German classical music world by Sturm und Drang — which is pretty interesting, given its title, Heimat (HYME-at, or “homeland”) and its contents: Lieder (LEED-ur), a.k.a. ballads consisting of German poems by the likes of Schiller and Wilhelm Müller, set to music by composers such as Schubert.

Lieder last enjoyed widespread popularity when everyone involved with their composition, arrangement and performance wore a frock coat. And yet, here’s Appl looking like 9 million Euros in a sharp-ass suit, doing the “Erlkönig,” a creepy poem by Goethe set to Schubert:

Hold onto your Hintern, friends: According to this trend piece in Die Welt (dee VELT, or The World), the slightly creepy Deutschland-ode is back in a big way. Appl, the unfairly handsome Singer-Sarsgård is going to Lied us to the homeland, and we’re going to like it.

Die Welt is basically the German Wall Street Journal (also, they published a hit piece of sorts on me once! It’s the most famous I’ve ever been), so it’s unsurprising that author Manuel Brug described the modern unpopularity of the “Germanest form of music ever” without so much as alluding to the political and historical reasons for this unpopularity — reasons, as you’ll see, which are about as subtle as the piano on “Der Kampf.”

Brug does go out of his way to note the diversity of the audience at a recent Appl recital (“You’d be hard-pressed to find a more racially diverse, knowledgeable and enthusiastic group elsewhere in the German capital”), and the “electrifyingly contemporary, universally human” quality he brings to the pieces — but what he does not so much as mention is how jarring it is for the rest of the world (and much of Germany) to see an album of Lieder, un-ironically titled Heimat with a perfect-looking blonde dude on the cover. (Like, perfect-looking, all right?)

Because guess what? The Germanest Form of Music Ever — and that word, Heimat — come charged with 1.12 jigawatts of untoward connotations from Germany’s past, specifically its entanglements with national identity.

First of all, as much as Europeans like to pick on us for being a rebellious young dipshit country that is apparently in the midst of its insufferable college-sophomore Ayn Rand phase, Germans should be careful, because Germany wasn’t even a thing until 1871. 1871!

Fine, that’s an oversimplification, but really: The German Empire (or Second Reich, as we know it now), wasn’t formed until almost the twentieth damn century. The first Reich was the Holy Roman Empire for chrissakes, of which all the German-speaking lands were still a part until eighteen hundred and six, when, of course, this happened. (All through grad school people kept mistaking me for someone in the history department, and I can definitely see why.)

This meant that even though, say, Prussia and Saxony shared a common language (more or less), they were different territories, with tangles of Electors and Junkers (YOON-kahs) and other government randos that no real American should ever have to care about. This made for some most excellent literary fodder: Heinrich von Kleist’s gripping novella Michael Kohlhaas hinges on a bureaucratic misunderstanding between Saxony and Brandenburg, in which horses are harmed and then Saxony gets set on fire.

But, it also made for a not-so-excellent sense of what being “German” actually meant. And meanwhile, Germans were hella jealous of their neighbors in France who clearly had enough of a national identity to throw a spiffy revolution. Roundabout the end of the eighteenth century, enter the fixers of all things: THE POETS.

Goethe was like, You know what we need to feel like a unified culture? Our own Faustus. Boom.

And Schiller was like, You know what else we need? A bunch of poems with soaring imagery that everyone can identify with. Boom.

And then later, Schubert and Beethoven were like, We should set those poems to music and then everyone will know them by heart, because classical music concerts are the YouTube cat videos of our time. Boom.

So in a way, German national identity — and any remotely unified notion of the deutsche Heimat — was an artificially cultivated concept foisted upon an eager public by the arts. It took less than a century to ingrain that concept so mightily that it could be invoked to scapegoat and marginalize an entire religion.

Yes, the reason the word Heimat is so charged today is thanks to the Third Reich and its propaganda, which included the simplistically plotted, Aryan-cast didactic films from the government-controlled UFA Studios, that ruled the deutsche Kino (KEY-no) during you-know-when.

After the war, there was even a brief and bizarre nostalgia genre called the Heimatfilm in West Germany, one that avoided any association with the Nazi past by simply pretending that entire business didn’t exist. My personal favorite is 1959’s Und ewig singen die Wälder (oond EH-vig ZING-un dee WELD-ur), or “The Forests Sing Forever,” a deeply technicolored, very sweaty melodrama by Paul May that taps into German viewers’ omnipresent anxiety about the possibly forthcoming nuclear apocalypse by completely ignoring everything. Also, there’s a bear.

Still, “national dress” aside, invoking un-ironic nostalgia for the German homeland hasn’t otherwise been überfashionable since about 1944.

Until now, I guess! Welcome to an epoch of renewed anxiety about nuclear apocalypse, and also, coincidentally, rising tides of nationalism, and also, coincidentally, the resurrected very German national music style! Sure, the USA is now leading this particular charge and most of our national songs are by Toby Keith and not Schubert—but Germany’s AfD, at least (a political party that hates fer’ners but loves trains) seems all too happy to follow our Lied.

Do I really think Benjamin Appl and his perfect cheekbones are complicit participants in something sinister? Of course not — the man’s just singing in a genre that suits him, and good for him and his intoxicating blue eyes. It’s not Appl that concerns me — it’s the oblivious puff piece in Die Welt touting an album called Heimat, recorded in the Germanest Form of Music Ever, that it calls “universally human.” One can’t help but wonder: What humans will be universally included in the next empire?

Roommate Recalled

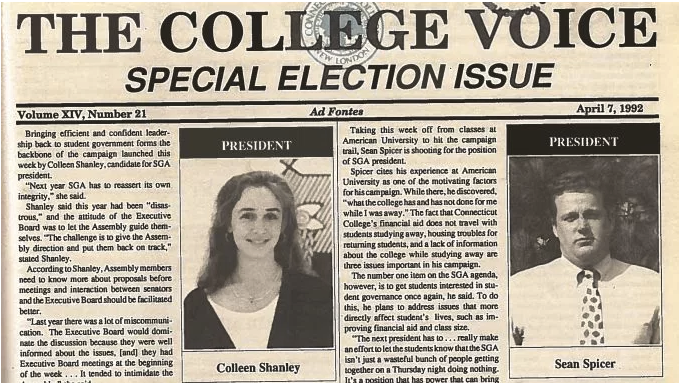

He would walk into the room and everyone would kind of go: “Ugh, Spicer.”

Awl pal Dave Bry was Sean Spicer’s freshman year roommate at Connecticut College (he wrote about it for The Guardian last year). In a recent interview with his alma mater’s newspaper, he goes a little more in depth about coffee mugs filled with dip spit, and the sailing club—sorry, the sailing team.

TCV: And so would you say he was well-known on campus? Well-liked?

DB: Um, no. Not well-liked. Not like hated. How can I describe Sean Spicer? Because he was kind of an interesting guy. He was very into, like, always having a sense of humor, and funny, and laughing and chatty. And that was something that was, you know, kind of pleasant about him. But he wasn’t so good at it. And he wasn’t very popular, I would say — he was like, he would walk into the room and everyone would kind of go: “Ugh, Spicer.” But he was aware of that, and so then would like, play with it, so he’d be like: “Hey, come on guys! It’s just me! Come on, let’s have a beer; we love each other! Yeah, come on — oh, I know you don’t like me, but that’s just because you don’t know me!” He’d put his arm around you, and kind of be like, “come on!” you know? And so it was this very interesting combination of characteristics, where you could tell he really wanted to be liked; he tried a little too hard. He brought — you know, we had this thing freshman year during orientation where you were supposed to bring one item that describes yourself, you know, that if you would bring to put in a museum about yourself it would let them know about yourself, and I remember he brought his fake I.D. And he said, “Yeah, this is my fake I.D., and it says a lot about me because I really like to drink beer.”

You can read the whole thing, and/or listen to the full audio of the interview, here.

Vintage Spice: Dave Bry Tells the Voice about Life with the White House Press Secretary

Translations For Spring

The Adventures of Liana Finck

Liana Finck’s work appears in The New Yorker, in Catapult, and on Instagram.

Daniel Brandt, "Eternal Something"

Remember what it was like when things still made sense?

When they say “you couldn’t make it up” they mean “because no one would believe it.” I don’t even know anymore. At least music is still good. This, in particular, should distract for a few moments. Enjoy.

Aberdeen, Maryland, to New York City, April 10, 2017

★★★★ It was warm now and the guns were pounding in the distance, the thumping too immense to be mere thunder. A red-shouldered hawk went screeching overhead in the bright sky. The light was harsh through the still-leafless branches. Spring beauties were blooming in the fallen leaves by the brush pile in the woods. The old pruning saw was dull and slow but the branches were so dead they would snap if the saw could be gotten halfway through them. A chickadee sang its desires in A major. The children had to be reminded to carry the coats they’d needed to wear two days before. More hawks were out above the highway at intervals, and at shorter intervals, in kettles, came vultures upon vultures, casting vulture shadows on the road before the car. Here and there were smears of fur and gore. Flags rippled a little faster than was attractive. The Ikea parking lot was as comfortable as the Ikea parking lot could ever be. The sun mellowed into goldenness. Unseen birds twittered in some darkening pines on the corner by the garage. The smell of people’s dinners pushed its way out the open side of a restaurant.

I Hope The New York Times Never Gets Rid of Its "Critical Shopper" Column

And maybe even lets Matthew Schneier keep writing it for a while.

Tuesdays used to be good, some time before now. Maybe that stopped when new-record releases and shifted to Fridays and newsdumps shifted to Every Single Day? Everything I read and consumed today, including the weird prepared quinoa salad from a juice bar in Downtown Brooklyn, was bad, with the exception of this very pleasant surprise: a delightful installment of one of the New York Times’s best columns, Critical Shopper, from Times Styles reporter Matthew Schneier:

Where Masters and Mistresses of the Universe Can Have It All

Schneier tells us right upfront he is our “stopgap” correspondent, but I hope he stays on longer, because he’s written up his trip to The Mall Of The Future (Brookfield Place) with just the right mix of delight and wit necessary for the job. The piece contains fun and funny writing about wildly unaffordable clothes without dismissing the conceit entirely (a trap some critics tap dance all too readily into). Schneier toes the line between credulity and whatever the noun for “shrill” is (“shrall” gets my vote).

“Where would you wear these?” wondered Hannah, the girlfriend I enlisted to vet the Saks women’s assortment with me. She had in her hands a pair of Miu Miu slides, upholstered in a faux fuzz the color of Cookie Monster and topped with imitation pearls ($950). They were never meant for the touch of the subway platform.

Anyway the Times has a bad track record of killing things that are good, like blogs and sections devoted to bridge (the card game) and metro news. I just hope it doesn’t do that with this very frivolous-seeming but extremely important bit of recurring content. To me it’s like the “Tables for Two” of the Times—a perfect writing exercise; a piece of critical writing about an experience most people will never have, whether because they can’t afford to or because they don’t live nearby. It’s also a showcase for good writing from young guns. (Lol, hi.)

It wouldn’t be a love note to “Critical Shopper” without a shoutout to Cintra Wilson—the one, the only, the sassiest voice in shopping critically. I miss looking forward to her writing, whether it was about Thom Browne or J.C. Penney, because she made me feel something. Her opinions about specific items of clothing didn’t even have to be right or wrong, per se—they were just good and good to read. Here’s hoping we get more Schneier.

No Good War

Thoughts on Syria

Even Barack Obama’s guiding principles for weighing the wisdom of military action, so cautious in comparison with those of his neoconservative predecessors, betrayed an eagerness to look away from what war does to those caught in its path. “I don’t oppose all wars,” he said in a 2002 speech. “What I am opposed to is a dumb war. What I am opposed to is a rash war.” He lived up to this self-description, with a few exceptions, during his eight years as President. Except for his “red line” comments, his decisions regarding Syria were thoughtful and deliberate, and none of them have permanently damaged America’s international standing. But opposing dumb wars isn’t enough. Smart wars should be opposed and avoided too, until the last moment and at all possible costs, because they are wars. All military conflict rips apart the social fabric in irreparable ways, and all the US and Russia have done with their careful, self-interested maneuverings is intensify and accelerate the process by which a dictator has reduced his unfree but still stable society to rubble.

There has been very little commentary on the situation in Syria since last week that hasn’t made the commentator sound like an idiot interested only in advancing his own agenda, but this, even if you disagree with it, will not make you ball your fists in anger and think, “Why should I listen to this idiot,” because its case is compellingly made. It’s a long one, so save it for when you have time.

Fresh Meat For Berlusconi

Is anything surprising anymore?

Here you will find video of former Italian Prime Minister Silvio Berlusconi cuddling and kissing several lambs that he has “adopted,” as a voiceover suggests that Italians “defend life” and “choose a vegetarian Easter.” It says something about where the world is in 2017 that this isn’t even the weirdest thing I’ve seen today. [Via]