Slate Takes a Crap on Your Monday Morning

It’s a perfectly reasonable Monday morning, people are going about their business, and blammo, Slate comes and makes a huge filthy mess of it with their bizarre ramblings about grapefruit. It’s just not right.

Andrew Bird, Lillian Schwartz and Oily Fried Potatoes

Violas! Have dinner with Joyce Carol Oates! Latkes at BAM. Groovy pioneer Lillian Schwartz gets her due at MoMA’s film dept tonight. And Andrew Bird at Riverside Church and Smashing Pumpkins at Barclays. (Details here.)

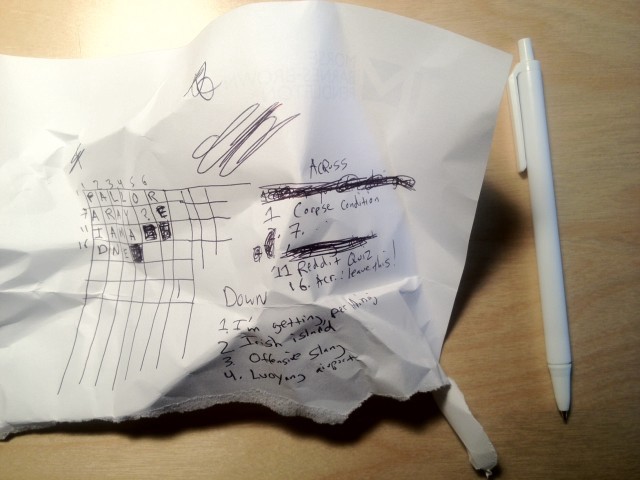

Solving The Broken Crossword Puzzle Economy

by Ben Tausig

The crossword puzzle can seem utterly authorless. If you haven’t caught the documentary Wordplay, or bothered to look up the name that appears in tiny agate type below the grid in The New York Times, you might join many others in assuming that the crossword is written by editor Will Shortz. Or volunteers. Or a computer.

In fact, crosswords are made by people (called constructors) whose status is roughly equivalent to freelance writers — that is to say, low. Puzzles are sent on spec to editors, who buy them or turn them down, and who fine-tune the ones they accept without, as a nearly universal rule, consulting the constructor. Submissions may sit in an editor’s inbox for months or even years before the author hears back. (A few months ago, constructor Tim Croce received an acceptance from The New York Times — for a puzzle he submitted in 2001.) Even after a puzzle is accepted, the constructor may not know in advance when it will run. Attribution comes in the form of fine-print bylines, and in syndication the author’s name is often excluded altogether. And this is true not just at The Times, but at other papers that run puzzles, such as Newsday and the LA Times. If you’re hoping for riches, you’ll be disappointed. Pay is — to use a puzzle term — olid (foul). Most outlets offer less than $100 for a daily crossword and less than $300 for a Sunday-sized, despite the huge number of readers who presumably buy the paper in part or in whole for the crossword, and despite the substantial labor and creative energy that construction requires. For aspiring constructors, things don’t look so rosy — but that’s changing.

The financial stakes of the crossword are higher than a casual solver might realize. The New York Times, which runs the most prestigious American crossword series, pays $200 for a daily or $1,000 for a Sunday, which is certainly more generous than its competitors. However, The Times also makes piles of money from its puzzles. Standalone, online subscriptions to the crossword cost $40 a year ($20 for those who already subscribe to the dead-tree edition of the paper). In this 2010 interview, Will Shortz, the paper’s famed puzzle master, estimated the number of online-only subscribers at around 50,000, which translates to $2 million annually.

Meanwhile, The Times buys all rights to the puzzles, allowing them to republish work in an endless series of compendiums like The New York Times Light and Easy Crossword Puzzles. In that same interview, Shortz called these “about the best-selling crossword books in the country.” All royalties go to the New York Times Company, the constructor having signed away — as is the industry standard — all of his or her rights. Visitors to NYTimes.com will also be familiar with the crossword merchandise — mugs, shirts, calendars, pencils, and the like — pitched aggressively by the paper, and perhaps also with the 900 number answer line, which still makes some money from a presumably less Google-minded segment of solvers. Finally, the crossword has a significant impact on overall circulation. Lots of people buy the paper, or even subscribe, in whole or part because of the puzzle. Of course the feature has expenses as well, including Will Shortz’s salary, the cost of testing, and so on, but these are moderate compared to the millions of dollars that the puzzle earns from a variety of revenue streams. And out of that total, constructors collectively earn well under $200,000.

To be clear, Shortz is not brandishing the ulu (Inuit knife) at this holdup. In fact, he has presided over a humane increase from $50 to $200 for daily puzzles and $150 to $1,000 for Sunday puzzles in his two decades at the paper. The last one, in 2007, came about from what he described as “long, careful persuasion with the Times.” (Shortz has also been a hugely important force in the popularization of modern crosswords; the darts in this article are aimed more at the Sulzbergers than Shortz.) The Times has been very conservative about further pay increases, and the issue of giving constructors royalties for republished puzzles has never been seriously raised, ostensibly because of the challenges of keeping track of the bookkeeping but more likely because constructors lack any clout.

PUZZLE-MAKING AS OCCUPATION

When I published my first crossword in 2004, I took a typical path, trying my hand at making a grid on a sheet of paper and, with some mentorship from old hands on the Cruciverb-l email list, eventually refined it to the point of saleability. My first acceptance came from USA Today, and ones from the LA Times and New York Times followed not long after.

This was a fairly standard path for a constructor. But less typically, I also reached out to alternative weeklies that I noticed didn’t run a puzzle, to see if they might be interested in supporting a new weekly feature. Before my Times puzzle had even been published, I was given a trial run at the San Francisco Bay Guardian. I developed an email pitch that promised a sometimes racy and opinionated puzzle with a focus on “contemporary music, film, food, sexuality, art, and slang.” A number of papers bit, including the Village Voice and Chicago Reader. The pitch became a syndicated weekly puzzle called Ink Well that I continue constructing to this day. Meanwhile, in 2006, I was offered the editorship of the then-newly launched Onion A.V. Club crossword, which was my first opportunity as an editor. Although longtime constructors told me in no uncertain terms that crosswords could only ever be a hobby, I was increasingly able to scrape together a living from those two features, along with some book contracts, and an assortment of freelance projects.

In fact, I made it through graduate school while splitting my mental energy between fieldwork methods and lurid clues. (Thing caught in the act? (3 letters) … STD.) PhD student stipends don’t go very far, especially if you live in New York, so puzzles were and remain a serious part of my professional life. My career in puzzles hasn’t been typical, but nor has it been unique; others have carved out careers by combining weekly features with book royalties and editing gigs, for example. Few of us, however, have any job security. Writing puzzles is a lot like freelance writing — except possibly even more marginal.

THE NEW CROSSWORD MODELS

The anonymity that surrounds puzzle construction undoubtedly helps to maintain the status quo. Puzzle outlets implicitly tell authors that they should feel lucky to have their work appear in a major paper, rather than entitled to honest payment and acknowledgement. And for those who construct only one puzzle a year (or in a lifetime), perhaps the satisfaction of seeing their work published is enough. But for those of us who construct more regularly — who may even consider the pursuit a livelihood — our minute share of crossword earnings is frustrating and unfair.

Until recently, papers like The Times had little incentive to change their policies. The only pressure they have ever felt came from the now-defunct New York Sun, whose editor, Peter Gordon, continually raised his rates to at least one dollar higher than what The Times was paying in order to be able to claim that he paid the highest rate in the country. Shortz would then, in turn, be compelled to petition the Times to raise its rates. But since The Sun folded in 2008, The Times hasn’t budged a single ecu (old French coin).

Today, though, things are a bit different. A number of alternative puzzles have become viable through online and in-app distribution. Features like Matt Gaffney’s Crossword Contest (xwordcontest.com) and Brendan Emmett Quigley’s twice-weekly puzzles (brendanemmettquigley.com) rival any major newspaper in quality — and surpass them in edginess: consider Brendan’s recent theme answer WAX AND WANK, clued as “Pleasure yourself after a Brazilian?” According to Brendan, “While I still sell puzzles to the Times, I find the speed at which print media operates too stifling. When I make a puzzle I want it to be out in the world almost immediately. Writing for the digital world allows that freedom.” The existence of alternative outlets provide an important shim (wedge) in the labor showdown between constructors and publishers. Puzzlemakers with their own sites have full financial control and access to a growing audience. However, not every aspiring puzzle constructor can launch his or her own weekly feature, and Matt and Brendan are self-published authors rather than editors in the main. What is needed is a more equitable model for constructor compensation in edited crosswords, digital or otherwise. What might such a model look like?

As I mentioned earlier, for the past six years I have managed and edited the Onion A.V. Club crossword, which recently moved to a subscription service after being dropped by the newspaper that launched it. As of last month, we are called the American Values Club xword (Avxwords.com ), and we continue to specialize in pop culture/dumb sex jokes. (Example: Caleb Madison’s recent “Deal with one’s period, perhaps?” (4 letters) … EDIT.) Rather than buying work outright from constructors, we offer a base rate of $100, plus a fixed percentage of all royalties — from apps, books, or anything else. As the feature has grown, payment has risen to an average of well over $200 per puzzle, surpassing The Times and all other outlets despite our comparatively tiny size. Furthermore, there is no effective limit to what American Values constructors might earn, which seems perfectly fair given that they are artists whose creative products are the sole reason the feature exists, let alone succeeds. This model benefits constructors, of course, by paying them a fair share, and it benefits the editor by incentivizing better puzzles. There is nothing arcane about these economics, and their implementation is a simple matter of having the will to put a better system in place.

All of the pressure in the crossword industry today pushes against fairness, but there is an opportunity to turn alee (away from the wind). If more editors come to recognize the upside of increased base rates and royalty-sharing — and especially if constructors grow to demand those things — then puzzlemakers might finally get the recognition and compensation they deserve.

Related: Seven Years as a Freelance Writer, or, How To Make Vitamin Soup

Ben Tausig is the editor of the American Values Club xword, available by subscription, and the author of the syndicated alt-weekly puzzle Ink Well xwords. He has been a freelance and syndicated puzzlemaker since 2004, and writes for sites like The Classical and Dusted Magazine, in addition to working on a PhD in ethnomusicology from NYU.

New York City, December 6, 2012

★★★ Cold seeped through the window glass and blasted through the open doorway of the apartment lobby. To the south, out on Amsterdam, the sun covered the avenue with a white shine. A cab had pulled over at an angle, beside a parked silver Mercedes, and the Mercedes driver was getting jumper cables out of his trunk. On Broadway, a vendor was selling hats with animal faces on them and scarves or shawls, the lightweight kind that used to be a luxury item. Downtown, a half-foot-thick facade threw a four-foot-long shadow on the adjoining building. At night, a walk/don’t walk sign had something stuck inside it, the way that seems to happen in winter, so the orange hand and the white person stayed lit up together.

Benzos And Opulence: At The Marrakech Film Festival

Benzos And Opulence: At The Marrakech Film Festival

by Ray LeMoine

This year’s Marrakech Film Festival has been happening in Morocco all week. During my time there, I saw only one film, but the festival itself was pretty cinematic. Tons of amazingly photogenic people swanning around, lots of gorgeous scenery, mindbending architecture to gawk at, a group of desperate people plotting escape (journalists), the whole deal.

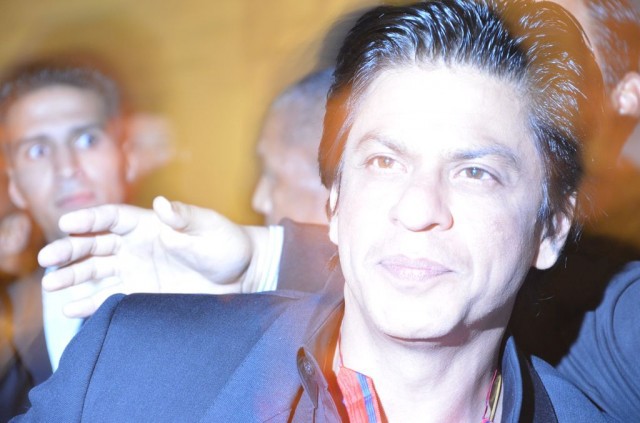

The opening dinner party was an Indian buffet at the new Taj Hotel, which had the stylings of a psychedelic Mughal palace. The food was disappointing, but the party proved great thanks to the cadre of Bollywood stars in attendance. This year’s festival featured a big tribute to Hindi cinema, and a slew of India’s biggest film stars came to town for the event.

This man, Shahrukh Khan, is the Tom Cruise cum Al Pacino of India. Only even more famous than those two combined. Actually, he’s the most famous actor on Earth. Suck it, Hollywood.

Around 1 a.m. at the opening party, I met some of the younger stars on the dance floor. A publicist with the group told me they were the Indian equivalent of the Twilight and Hunger Games kids. (Sorry for the this-is-what-it-would-be-in-America translation but that’s how I kept up.) Compared to young Hollywood, this contingent won on every count. Friendly? Yup. Beautiful? Indeed. Hard partying? Yes. They were pounding shots of Grey Goose at 3:30 a.m. When they handed me one, I puked on myself. They just kept drinking and dancing and laughing. No egos, no attitude. Young Hollywood, step it up.

The next night there was a formal tribute to Bollywood. Here is Amitabh Bachchan, the former “angry young man” of Hindi cinema, standing onstage next to Catherine Deneuve.

Working the red carpet is one of the most fun forms of journalism. You’re quarantined into a huddled pack with all the other journalists, yelled at if you move and harassed by publicists. It’s like war reporting, but with even more angry people. Arguing with publicists and asking famous people you don’t know dumb questions is super fun. Exhibit A: Ms. Monica Bellucci, the big star of the festival. “Monica, is it true about the boat?” I yelled, having heard a rumor about her early days in showbiz.

This netted me a strange look from this publicist, then a “Move on, please,” said in a sexy French accent.

The festival had an official disco called The So Lounge, which was only so-so in atmosphere but made up for it in generous free-booze policies and the deployment of an expat cover band doing Pitbull tunes. Marrakech has some serious discos. One could easily disco through 25 different insane party dens, amongst hookers, Euros and rich Arabs, until dawn in this town. There are casinos, too. And then the city is just amazing. Snails are sold on street corners and there are 26 local lamb varieties, all good. I also came away with distinct impression that you can buy hash from every single Moroccan male you meet. #hashtag #travelfact

It was at the discos that I learned about a rising young professional class called “fashion and style writers.” They’re not quite reporters, nor do they do much actual writing. They’re almost famous, being allowed access and proximity to the stars, making them semi-socialites. They wear colorful clothing including capes and scarves and get invited to things called “dinners,” which are like actual dinner but with less eating. (The dinner that Dior gave here was attended by Christian Louboutin, above, a humble cobbler from Italia.) Occupying the niche of fashionably stylish writer yuppie may represent the last hope for aspiring journalists to make real money. And as a bonus, you don’t even have to do any journalism. From my reporting, the greatest living young “fashion and style writer” is a gentleman named Derek Blasberg. He went to NYU. He’s now so almost famous that he hosts the aforementioned dinners, then writes about them. In effect, his beat is himself. Sweet gig.

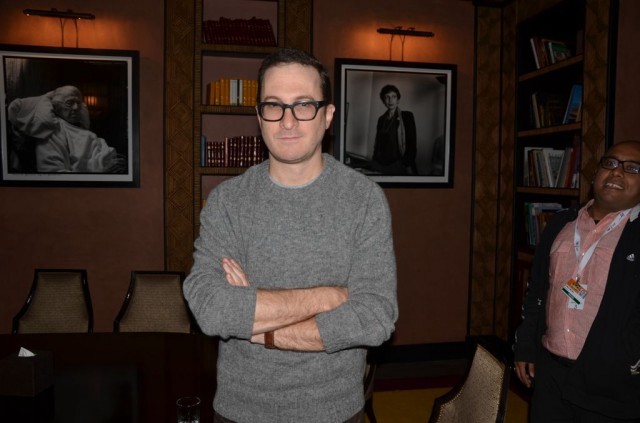

The one movie I saw was a French film about a woman who kills a bunch of people with benzodiazepine, a.k.a Valium, the very drug I bought at the pharmacy here and was on the entire trip. And pills are also the subject of the only major Hollywood feature screening at the festival, Silver Linings Playbook, that Oscar-buzzy flick directed by David O. Russell and starring Bradley Cooper as a bipolar wigger. It’ll screen at the festival this evening. Above is Darren Aronofsky.

The anything-goes-ness of the festival felt odd, politically. Morocco is still ruled by a monarchy; and while the Arab Spring hit here and brought change, there remained moments where even a visitor like me would brush up against these invisible threads of control. Like, attempting to click on this video, I’d get the message: “This video not approved by this country.” Funnily, at the airport, I’d picked the only English magazine they had, some nerd rag called Foreign Policy. And! There was an article about Morocco by James Traub, who writes: “Constitutional reform, by itself, will not be enough. Morocco cannot become a democracy as long as it has both a government and a feudal court that claims not to govern and therefore is unaccountable to the public.” In conversations with many young Moroccans, mainly of the Ultra (soccer hooligan) variety, I’d hear this echoed along: the revolution will come if the king doesn’t make more changes soon.

Holding a film festival in an authoritarian country confused me — should I be involved in this? But a publicist at the event told me this: “I’m working with artists, actual artists, to create art and then we get to show the art here. This society needs that more than the West.”

Ray LeMoine was born north of Boston and lives in New York.

Eat Less Fat Yourself Less Fat

“Forget dieting; just cut down a little on the fat in what you eat and you’ll lose weight. The confirmation that you can lose weight without eating less comes from a review of studies involving nearly 75,000 people — none of whom were trying to lose weight. The pounds fell off when they changed to a diet containing less fat.”

— Apparently, if most of what you can eat is food that is no fun, you will decrease the sad number of pounds you are shuffling along with. I imagine this would also work if you cut down a little on the alcohol, but I will allow Science to figure that one out before I make any plans.

A Chat With Drummer Karriem Riggins About Bending Genres To Make A Career

A Chat With Drummer Karriem Riggins About Bending Genres To Make A Career

by John Lingan

Few musicians move so fluidly between genres as drummer and producer Karriem Riggins. As a jazz sideman, Riggins has played with jazz artists like Diana Krall, Milt Jackson and Oscar Peterson while simultaneously contributing beats and productions to records by Common, J Dilla, the Roots, Erykah Badu and others. 2012 has been a particularly fruitful year for Riggins. It began with his appearance on Paul McCartney’s most recent record, Kisses on the Bottom, in which the former Beatle covered and channeled the prewar pop songwriters that he listened to as a child. And in October, Riggins released his first solo LP, a kaleidoscopic instrumental hip-hop album called Alone Together, on Stones Throw Records.

Hip-hop and jazz have overlapped and fed each other for decades, but the genres remain stubbornly separated in the marketplace despite attempts by artists to bridge the gap from both sides. Stones Throw, with an aesthetic that prizes crate-digging and esoteric sounds, does as good a job as any label on earth at erasing the separation between the two. I talked to Riggins about how he’s managed to earn a living by stretching his talents in as many directions as possible.

JOHN LINGAN: You’ve been making beats and playing drums as a sideman for ages. How did a solo record finally come together and what was the process like?

KARRIEM RIGGINS: I had an idea to put Alone Together out for some years. And once I got on Stones Throw, it took maybe a year to pull most of the songs together. Some of them are a little older, most of them are more recent.

A lot of the ideas sparked from samples. This was more about exploring the raw side of my beat making. Showcasing a lot of chopping, the raw element of hip-hop. Most of them started with loops, and I played on top of some of them. But the process is different each time; I try to approach each song by stepping through in a different way. These are songs that I really didn’t hear anyone on, they speak on their own. I’m sure there’s an MC or a singer that could do them justice, but I think they stand alone.

Stones Throw Records has, over the years, built up an incredible reputation. What’s been your experience with them so far?

I met [Stones Throw founder and president] Peanut Butter Wolf and Madlib, pretty much all the guys over there, through J Dilla. They don’t really have much creative input, they leave it to the artist to have creative control. I have the freedom to do whatever I want, and that’s a blessing. That’s a really important label right now. They’re putting out vinyl, they’re putting out cassette tapes, they stay true to the essence of the music, all the artists are different. They have a wonderful, beautiful thing going on over there.

Is it different than other relationships you’ve had with labels?

I’m such a chameleon, and I think that’s why it’s such a great home. The music they go for is really just heartfelt music. And that’s the home for me. I’m comfortable there.

I had a connection with BBE, back when Dilla did his Welcome to Detroit record. We talked about doing a project. But just being a producer, being a musician, going on tour, that wasn’t something I could commit to back then. I think now, I felt it was just time to get with a label that was supportive and so I set that up. People have been waiting for a while, so I thought it was time.

So where did this all begin for you? When did you commit to music as a career?

I’ve always wanted to be a musician. I started playing drums when I was three. My dad’s a jazz musician so being around him at rehearsals influenced my love for music. And I loved hip-hop at the same time. That’s what was going on in the neighborhood, with my friends and peers. It’s always been a part of me.

I didn’t start making beats till the 7th or 8th grade. I got my first drum machine, an MPC-3000, in 1996. Bought that from DJ House Shoes, a real ill DJ from Detroit, living in L.A. now. In high school I was just toying around, looping up my drums. I did plenty of that. And I was really seriously buying records then as well.

First and foremost, being a musician taught me about work ethic, about practicing, trying to be the best I can be on my instrument. And I’ve tried to apply that to the other parts of my life.

And who were you listening to back then, in either genre?

A Tribe Called Quest was very influential, and all the other groups that incorporated jazz and hip-hop. Pete Rock and CL Smooth, that was some of my favorite music back then. Black Moon, Gang Starr, that was my daily music. I still listen to it, but that was the blueprint for what I do now. The pioneers.

[At the same time,] every time Wynton Marsalis came to town I’d go to see him. Reginald Veal was on the bass at that time, Herlin Riley on drums. And when Branford came I’d go to see Jeff “Tain” Watts [on drums]. They inspired my whole young generation. And of course all the guys in Detroit: Lawrence Williams was a big drummer here. Bobby Battle. Roy Brooks. Kenny Cox. Michael Belgrave. Having all that around, and seeing all these different guys coming to town, made an impression.

How’d you make the leap to professional musician then?

I went straight to New York when I was a senior in high school. I met Greg Hutchinson, a drummer from Brooklyn, one of my favorites. He came in to town with [trumpeter and bandleader] Roy Hargrove and he met me after a gig. I think I sat in on a jam session and he really liked what I was doing. So he gave me his number, said if I had any questions he’d point me in the right direction. He really helped me out.

He told [legendary vocalist] Betty Carter about me and said she may call about her new program called Jazz Ahead. She called and then flew me to New York to do that series of workshops and two shows at the Brooklyn Academy of Music, and another at the Apollo. With the money I got from those shows, I never went back to Detroit. I stayed there for years, living in like three different places over the next couple years. There were so many people there, so many young musicians. It was so inspiring to see level these guys were on.

When was this? How did the New York scene differ from Detroit’s?

This was 94. Detroit was great because there were a few venues that let us work out whatever we needed to work out. But moving to New York, there were so many super-serious musicians playing at an advanced level. Being around that was bananas. And so many jazz clubs, so many opportunities to hear so much music. From reggae to calypso to straight-ahead jazz to funk. Everything was there. Hip-hop — Guru was doing his Jazzmatazz thing. I mean, I got around. I didn’t get to bed ’til 7 in the morning every night. There was so much knowledge in that city. I learned a lot.

I had maybe a couple gigs a week, but the majority of the time I was practicing. I’d wake up about probably at noon, practice ’til about 7 o’clock, and then bounce around all night trying to hear new music. That was my school. That was the daily scene.

So you were relatively deep into a jazz career before you made any headway in hip-hop?

Oh, definitely. When I bought a machine, I think that’s what pulled a lot together. And having a chance to link up with Common. When I met Common, he hipped me to a lot of different things in hip-hop that inspired me to do it. I had joined Roy Hargrove’s band in ’95 and met Common near the end of 96 at the Jazz Showcase in Chicago. He’s one of my best friends to this day. When I first went to Chicago he came and took me around, played me music. I learned from being around a true MC who’s a part of the essence of hip-hop. That’s what inspired me to start making beats and make a career from producing, even rapping.

I didn’t really start producing ’til I moved back to Detroit. That was around 96, early 97. I bought my machine and kind of starting to go deep into the practice room on just chopping samples and finding loops.

Why move back to Detroit if New York was so mind-blowing?

I was touring so much, it made no sense for me to spend that kind of money on an apartment. I was touring ten months out of the year, it was just a money saver. I was in Roy’s band, I was in Mulgrew Miller’s trio, and after that I was in the Ray Brown trio. And I played with Ray Brown for about four years, and that was like going to school again, Ray Brown being a pioneer on the bass. I learned so much about bebopping and approaching arrangements. I learned more about Oscar Peterson and Nat King Cole… I learned so much music from him. That was the highlight of my life.

Did you already know Dilla when you came back to Detroit?

No, I met Dilla through Common, and that was in 96. Common came to Detroit to get beats for One Day It’ll All Make Sense, but the beats that Dilla submitted for that didn’t make that album. That’s when we met, and they started working on Like Water For Chocolate after that.

Initially, I didn’t know about Dilla’s music until I bought this Busta Rhymes remix album, and Dilla had a few remixes on that. And I thought, “Who is this cat Jay Dee? This is crazy.” Then I got the Slum Village cassette and my head was just blown. “He’s my favorite producer and he’s from Detroit!” I didn’t even know he was from the D.

So when Common brought me over to meet him, I saw his setup and it was crazy: Just two turntables and an SP-1200. And an MPC. I was thinking he had all kinds of EQ stuff and crazy mixers, but it was so minimal. He was sampling from cassettes… it blew my mind, seeing how he worked.

I’m a Donuts obsessive, so I’ll try not to make this all about him. But what was his musical background. Did he play traditional instruments?

He could play a little on all the rhythm instruments, just enough to get his point across on a song. I don’t think he would have the chops to do live shows, but he knew enough about music and his ears were wide open. I know his dad was a soul artist as well. He was around music all of his life. It could only be something like that, to put out the kind of music he put out.

What was your first introduction to the hip-hop scene?

On One Day It’ll All Make Sense, the final track [“Pop’s Rap Part 2/Fatherhood”], Common’s father did a poem over one of my productions. That was the first work I ever did on a hip-hop record. But it was kind of jazz influenced. It wasn’t a hip-hop song. The first hip-hop song that I produced on my drum machine, Dilla bought it and put it on Welcome 2 Detroit, and that was “The Clapper.”

To tell you the truth, I’ve never been involved in a “hip-hop scene.” I was just fortunate enough to hook up with Dilla and Slum Village. It’s just been kind of like a family thing, I’ve never really participated in a scene. I don’t think I was even in Detroit when the scene was really popping. I was in New York. I’ve kinda just been a jazz head who happened to be there, listening.

Did your hip-hop friends have a similar jazz background as you?

Dilla definitely knew jazz. I was surprised to see some of the records he had in his collection. He never sampled them, but I know he listened to them. Common, I would say the same thing. He knows good jazz music. And he’s open to learn more. I just want to be around people who are open to learn more. Not people who shut it off. There’s so much to learn.

That’s why I love being around Madlib. It’s so inspirational. Last time we took a road trip, digging, was some years ago. We were in Indiana and he pulled out some old issues of Downbeat from, like, the 60s, and we read those on the road trip. I like to be around people like that.

How about Paul McCartney and Diana Krall? Not many people get to go from BBE to Verve Records and the Beatles.

Of course I’ve always been a fan of the Beatles’ music, and I’ve been hearing them since I was a small child. And I never thought in a million years that I’d record with Paul McCartney. I got the call from Tommy LiPuma, a great producer. And the rest is history.

It was an incredible experience recording with Paul. Paul’s a great person and it was wonderful just being around him, hearing his stories. Just seeing him work, hearing his voice, how strong his voice is. He’s very inspired in the studio. He’ll come up with ideas it’ll just be like, “Come on, guys. It might not work but let’s try this, let’s go. Bang.” And it’s classic. [Laughs] I strive to be that.

And hooking up with Diana, she’s also been through the school of Ray Brown. I met her through Ray Brown in fact. He had a record called Some of My Best Friends are Singers, and I met her around that time. When her last drummer left she gave me the call. And now I’ve been working with her for eight years.

With any artist, knowing where they come from musically, what they really want, that’s huge. As a producer, too. So I had to check out a lot of stuff she was into, and now I’m into it as well. She hipped me to a lot of music — Peggy Lee, a lot of Nat King Cole. I dug into a lot of Nat King Cole. There’s a certain sensitivity in that music, you have to learn it like a different language. And it’s fun because she’s into a lot of different things besides jazz, like punk or soul music. It’s a great experience working with her.

Where are you going now? What’s up next, and what collaborations or styles do you still want to explore?

I want to do everything. I want to do rock. I have a straight-ahead jazz album sitting here that’s ready to come out. I have half a rap album that I’m doing. It’s all timing, let this one breathe and let people connect to it. Then I’ll see what comes next. I know God will lead me in the right direction.

With Madlib, I’ve got about nine or ten albums of… I don’t want to call it ‘jazz.’ But it’s really interesting music. Hopefully some of that will come out soon. A couple tracks came out on his record Yesterday’s Universe. And hopefully we’ll get back on the Supreme Team, where we’re both rapping. I’m also doing a project with Common in the near future. Using a lot of live musicians, incorporating some machine work, just mixing it up.

I’m doing so much hip-hop right now, in January I’m doing some DJ dates. Then in February I’m going out with Diana again, doing a tour of Canada. It’s balanced, that’s the only way I could do it. I feed from everything I do, I need all of it. Like vitamins.

Previously in series: A Chat With Ted Leo About “The Weird Small Business” Of Indie Music

You might also enjoy: 100 Fantastic (Not Best!) Songs From 2012

John Lingan’s writing has appeared in The Quarterly Conversation, The Morning News, Slate, and other places. Follow him @busybeinglingan. Photo by Randy Miramontez / Shutterstock.com.

Seven Amazing Videos From the Last Lunar Mission, 40 Years Ago

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wo3-fuYKWB4

It was 40 years ago when humans last made the effort to visit another heavenly sphere, on the Apollo 17 mission that launched on this day in 1972. But astronauts Eugene Cernan and Harrison “Jack” Schmitt didn’t just walk on the lunar surface — they also drove around in a dune buggy, and also skipped around while singing songs. Nixon was so angry about this expression of joy that humans were banned from every visiting the moon again.

That is not exactly the reason why humans have never left the bounds of low-Earth orbit in the four decades since our last lunar mission. But it was the beginning of a general pullback by NASA and America’s space ambitions. We have routinely sent people onto rickety space stations and flying back and forth on a cumbersome space shuttle based on 1960s technology, and even these modest missions have been plagued by tragedy and failure.

An important part of science is kicking rocks down a hill, on the moon. It proves how rocks work!

And here’s an astronaut skipping and hopping “like a kangaroo.” No wonder a worried America got tired of this tomfoolery. Things were not exactly great back on Earth in 1972, and these one-percenters are doing the bunny hop on the taxpayer’s dime?!

Mission Control calls astronaut Harrison “Jack” Schmitt “twinkle toes” in this clip. Where is the dignity?

Schmitt was so mad, he threw a hammer on the moon. Just like Thor!

While off-road vehicles here on Earth are about the dumbest and most destructive “hobby” humans have managed to invent, cruising around the moon in this lunar rover is okay because it’s for science!

And then the lunar module blasted off, We were going to have Martian colonies by now, right?

The Rolling Stones, In Order

23. Dirty Work

22. Bridges to Babylon

21. Steel Wheels

20. A Bigger Bang

19. Their Satanic Majesties Request

18. Voodoo Lounge

17. Emotional Rescue

16. Undercover

15. Goats Head Soup

14. It’s Only Rock ‘n Roll

13. The Rolling Stones, Now!

12. 12 x 5

11. The Rolling Stones (England’s Newest Hit Makers)

10. Between the Buttons

9. Out of Our Heads

8. Aftermath

7. Some Girls

6. Black and Blue

5. Beggars Banquet

4. Tattoo You

3. Let It Bleed

2. Sticky Fingers

1. Exile On Main Street

Related: Exile On Main Street, In Order

U.N. Climate Change Talks End With Plans To Talk About This Again Next Year

Did you forget to stay up late waiting for results from the U.N. climate talks in Doha? Well, you’ll be happy to know global warming is solved thanks to a bold consensus decision to take aggressive international action on carbon emissions and sustainability. No, wait, that is not what happened. Here’s a typically sunny reaction: “It’s very, very depressing. There is nothing [in the text] at all on finance, nothing about emissions reduction, it’s all about workshops and talk shops. There is no commitment by [by rich countries] on anything.”

Then again, “low expectations” were the only expectation at all. Sorry, polar bears and etc.

Photo by Popova Valeriya, via Shutterstock