Robert Bork, 1927-2012

Robert Bork, whose unsuccessful Supreme Court nomination alerted conservatives that if they wanted to be confirmed to the bench they needed to obscure their retrograde views on equality by responding to any and all questions with bland, affable baseball metaphors, has died.

Blogs Snatched By Giant CGI Eagle!!!

The Blog Lord Giveth and the Blog Lord Taketh Away. (Well, nine hours later.)

Professor Of Shiny Surfaces Misquoted To Comic Effect

“Because of an editing error, an article on Monday about scholars who study paperwork misstated, in some editions, a word used by Craig Robertson, an associate professor of media and screen studies at Northeastern University, to describe a phenomenon exemplified by the history of the filing cabinet and the passport. He said they were part of the ‘paperization’ of everyday life in the early 20th century, not the ‘pauperization.’”

Things to Do That Aren't Listening to That Damned "Hallelujah" Song

There is a panel tonight at the 92Y Tribeca during which there will be three performances of the song “Hallelujah.” My God. Even while Leonard Cohen is playing at “Barclays.” But Max Richter does Le Poisson Rouge! And if you would like some hilarious “experimental” theater, and yes you would, there’s “The Ultimate Stimulus” at Dixon Place, a tale of a loopy economist’s TED-ish talk gone wrong.

The Long, Twisted History Of Marvel Comics: A Talk With Sean Howe

The Long, Twisted History Of Marvel Comics: A Talk With Sean Howe

Marvel: The Untold Story is a meticulous reconstruction of the history of the other Marvel Universe. It’s the tale of the men and women who were creating all the characters and plotlines of the Marvel empire that currently dominates Hollywood. I’ve been as big a fan of the medium as anyone, for decades now, so I was glad for the opportunity to talk by phone to the author of this obsessive work, the very pleasant Sean Howe, who spent three years of his life writing this history. The book makes a great gift, as I hear Secret Santa season is upon us. And his Tumblr, it should be mentioned, is an invaluable companion to the book, with untold stories and the ultimate fates of some of the creators of the most popular characters of American culture.

Brent Cox: I never dreamt that anyone would get around to writing a book like this. So I have to ask: What were you thinking?

Sean Howe: I was waiting for someone to cover this story for a long time. I noted that every time that I was reading fanzine interviews with these comic book creators that they were telling this story that was a lot different than the official version.

What’s your own personal history with comic books?

I learned how to read from comic books when I was four. I was first sounding out words from comic books, and when I was eight was probably the first time that my dad brought me into a comic book store.

What store was it?

Dream Days, in Syracuse, New York. I’m 38; how old are you?

43. And same story with me, but my first store was Eide’s Comics, in Pittsburgh.

The thing is, this was before (as you well know) the Internet, and there was something about the comic book world, you felt like you were part of something bigger. I remember this feeling of, like, oh my God! I live in this small town and I’m isolated from so much, and I’m not into rock ‘n roll yet, and this is my first pop culture connection to the outside world.

In choosing to writing the book, you’re contemplating that more people than just comic book fans (like us) are going to read it. What do you think the appeal of the “inside baseball” story is?

I think that the story of Marvel Comics is a really clear way of telling the story of pop culture, and I think that the collisions between art and commerce are things that have application to pretty much any other creative industry. The thing about Marvel’s history that really highlights those battles and those contradictions, is that it’s this huge overarching narrative. If you think of the story of the Marvel Universe, the ur-story —

Yes, the continuity.

It’s almost like this giant river that’s rushing by and all these people throw their ideas into the river, and the river just keeps going without them. These creators for the most part have no financial ownership, and also no creative ownership. Eventually their creative contributions can be overruled as well. Television I guess is a little bit like this, but in television people are well paid.

Are people traditionally well paid in comic books? You do cite dollar amounts a couple times, but I imagine that you were trying to be circumspect.

There have been times where comic books paid well.

You mentioned writer Scott Lobdell making $85,000 a month?

Yes, in the late 90s, writing the X-Men titles. But the thing is, that’s not unusual for someone who would be a top TV writer. It’s only unusual in the world of comic books. And that was only at the height of comics’ success, on a title like X-Men.

One thing that really comes out in the book is how distribution is really the engine that drives the entire industry, from the late 30s when the entire thing was run by a handful of guys in midtown Manhattan who were basically magazine publishing companies fighting over newsstand rack space, and in more recent history, with comic book publishers winnowing the distribution market by acquiring distributors. Do you think that’s something specific to comic books?

I think that distribution is definitely a huge part of the story, and in fact I think that it’s probably the main explanation for why comic books are in the situation they’re in now. When the comic book specialty store market imploded, it’s not like comics still have that newsstand access.

You can’t still go to 7–11 and find them on the racks.

Exactly. And I don’t think that that fact is necessarily the fault of the comics industry. They were having trouble with newsstand sales in 1978. It’s just that they were able to put it off being a huge problem by finding the direct market. They never abandoned newsstands, rather, the newsstands abandoned them.

Another thing that struck me as I was reading is the ways in which the industry acted as a meat grinder. You don’t meet a lot of people that have been in it a long time that are happy. There’s an episode from the 70s with Stan Lee advising someone not to get into the business, and Frank Miller’s 1994 industry seminar keynote following Jack Kirby’s death is a real downer:

Marvel Comics is trying to sell you all on the notion that characters are the only important component of its comics. As if nobody had to create these characters, as if the audience is so brain-dead they can’t tell a good job from a bad one. You can almost forgive them this, since their characters aren’t leaving in droves like the talent is.

And yet it’s a field full of young hopefuls, eager to sign up. Why is that?

It’s their childhood dream and they’ve been pursuing it. I think that at this point, there’s a greater likelihood of people being happy. Not because the comic book industry is any kinder, but because people are going into it a little more clear-eyed than 30 years ago.

They’re forewarned.

Yeah. That’s one thing that’s been kind of amazing is to get a lot of feedback on this book, and there’s so many comic book readers that are just shocked by the facts that are in the book. They can’t believe that so many people were so screwed over and so many people were so unhappy at different times.

I had no idea that Jerry Siegel [the co-creator of the most iconic superhero ever ever, Superman] ended up working as a proof-reader at Marvel in the 60s.

That was a crazy moment. I had heard that, but then Chris Claremont was telling me that when he was like, 22, seeing this old guy, Jerry Siegel, and thinking to himself, “I’m never going to end up like that.” And now flash forward 40 years, and Chris Claremont is saying, “Now Marvel won’t let me write any comics. Characters that I created have their own books, and Marvel won’t hire me to do them.”

Ms. Marvel, which Chris Claremont described as Marvel’s attempt to “appeal to a female audience, trying to make her a hip, happening, 1970s woman striking out on her own.”

How many creators did you talk to?

Somewhere between 100 and 150.

And generally speaking, how many of them are happy?

Well, that’s hard to say. A lot of them are no longer in the industry.

By choice, or…

You know, they’ve retired or — it’s hard to generalize. Gerry Conway [co-creator of The Punisher] ended up being an executive producer of “Law & Order: Criminal Intent,” so some people found some really nice outs. And then if they still are in the industry, very few people that are still in are going to tell me they are not happy.

Well, to think of these professionals as a group with a shared peculiar experience, like professional baseball players from the 60s, say, is there still a “joy of the game” in them?

Yeah. There is. There are instances where people pretty much have given up on thinking good thoughts about comics, but I think those are rare. The more common arc for these people is that they had some of the best times of their lives working on comics, whether they were in the office or they were a freelancer. And then something with the business turned, and as you know from the book, this happens cyclically, so it doesn’t even matter when they were working. Either they working in 1980 and something happened and everyone became unhappy, or it was 1996 and everyone got laid off. And then they go through a period of bitterness, and then they put it into perspective and they move on with their lives. Maybe they don’t work in the comics industry, maybe they work in advertising, or they have a start-up company, and they have still have their fond memories of the good days, and almost to the person have a great memory of when they met Stan Lee and he was super nice, and now they may or may not read comic books themselves, but they’re not completely at odds with the idea of Marvel Comics necessarily.

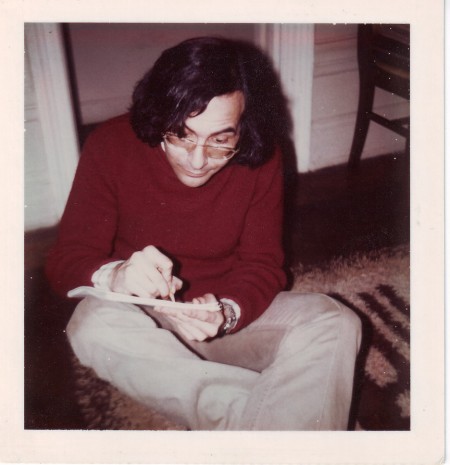

It’s one of the things I remember [Howard the Duck creator] Steve Gerber’s collaborator and one-time girlfriend Mary Skrenes was talking about how he never wanted to do anything more than write superheroes, and that became a big problem for him, just because all he wanted to do is to write these superheroes, and you only had Marvel Comics and DC Comics, and they weren’t treating him well, but he just didn’t know what to do with his life.

Steve Gerber in the 70s. Courtesy of Howe’s Tumblr.

Like he was someone that was born just to do that one thing.

Yeah.

Speaking of Claremont and Conway and Gerber, how many of your own personal heroes did you get to talk to for this thing?

Hm.

Let’s geek it out a little bit.

I don’t know that I — maybe it’s that I’ve been through the process, but I don’t remember being that star-struck. Certainly, the ten year old in me was excited to be talking to Frank Miller about Daredevil, and what was going on in his life when he was doing that, that was pretty thrilling. And talking to Stan Lee is like talking to an uncle you haven’t seen in 30 years, and there’s just something about the timbre of his voice that can send you back to childhood.

He’s been living the gimmick for more than 50 years.

Right. You’ve heard his voice in the Saturday morning cartoons since you were a little kid. It’s a very comfortable voice. And just that alone is kind of a thrill.

Did you get a lot of resistance from people when you were trying to research this?

No, not really. I mean, people were sometimes were tight-lipped. I would say that the biggest obstacle would simply be that people who work in the comics industry are afraid of burning bridges, professionally. Not in the sense of talking behind anyone’s back, or anything like that, but people are afraid that if they say something critical, it’ll be bad for their career prospects.

Another thing you covered well was the legal issues that run through the industry, the IP and the struggle between Marvel and the creators.

They’ve always had lawyers, but I think Marvel really started nailing down the rights in the mid- to late-60s. You know in the upper-left hand corners of the books from the 70s and the 80s, with the heads of the characters of the book?

Yes.

That’s not to help the reader identify the books. Those were put there for trademark purposes.

I did now know that’s why those were there! So they would trademark the little floating heads?

Yeah. Actually, let me look. Yeah, there’s a little trademark symbol next to them.

Actually, that’s something I’ve been wondering reading the books, and actually for years. I have experience in entertainment law. How do you copyright a character? Because you can’t, in my understanding, as copyright protects only the fixed expression of an idea. So you can trademark a character’s name, but…

They copyright the actual printed issues.

Oh, okay. But you hear creators talk, about how they want the copyright in the character they created…

If you look at the actual filings, there won’t be a lawsuit over the character of Captain America, but what they actually cite is “Captain America Comics” issue number one, and that’s the copyright that they’re going after.

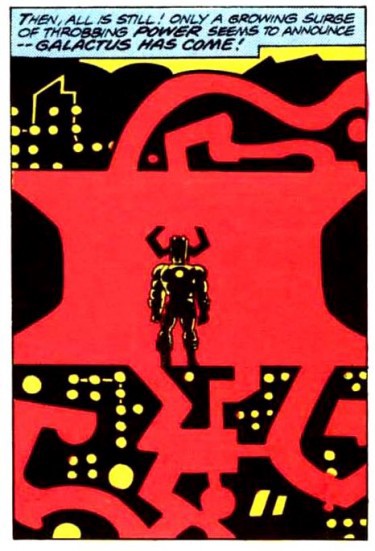

Galactus art by Jack Kirby. More here.

You do a very good job of constructing a straight-forward narrative. How do you stick to this narrative and not superimpose your opinions on some of the controversies that pop up?

Obviously, I have my opinions and my biases, and those are going to come through, whether explicitly or not. I felt like, especially within the world of people that write about comic books, there’s no shortage of polemics. There’s a lot of really strong opinions and a lot of rhetoric, and I thought it was really important to just lay out the facts of what happened, and to present, for example, this is what Jack Kirby said happened, and this is what Stan Lee said happened, and not try to contaminate those facts with arguments. I think that I’ve done it in such a way that people can draw pretty informed conclusions about the way things happened. But I don’t know who, Jack or Stan, did more in creating the idea of the Fantastic Four, say.

And nobody ever will.

And probably no one ever will. Who knows if there will be unearthed documents at some point? But it’s probably not going to be an eleventh-hour Stan Lee revelation.

There’s not going to be a security camera that recorded that.

Right. But what I did find was things like Stan Lee talking to someone in 1969 about how he was somewhat disillusioned with Marvel Comics and he wanted to bring Jack Kirby to Hollywood with him. And I’ve read before Stan saying that that’s what he wanted back then, but you never really know, when it’s 30 years ago, how true that was, or what the spin was, but when you hear a recording of someone talking about their current feelings, that’s really valuable.

This also comes up a lot in the book, professionals worrying at various points in history that the industry is not going to be there in five years. Do you think the industry is going to be here in five years?

Yeah, I think so. I think it may very well go through some really tumultuous times. For one thing, it’s Time Warner and Disney who control the biggest comic book companies. Maybe it’ll be that they just start putting out graphic novels on an irregular basis, but it’s not like they’re just going to walk away from money. I know that Marvel is profitable. I’m pretty sure that DC is profitable on the publishing end. I mean, on one hand, it’s kind of annoying that Marvel’s bottom line, the way that they’re set up, they insist that the publishing be self-sufficient, which means that they won’t use their movie money to subsidize experimental, loss-leading creative ideas in the comic book world.

I was looking at some current sales numbers this morning, and I was shocked. They’re low. You know, some titles are selling only 6,000 copies a month. It seems that the economics of it are confusing. But I guess if you have some books that are selling 175,000 copies…

And you’re charging three or four dollars, and, you know, they’re not paying anyone $85,000 a month anymore. Plus you’ve got a pretty lean staff of editors as well. There’s not a huge amount of overhead.

So are you going to write a book about DC now?

[Laughs.] I don’t have any plans to write a book about DC, but the news of [influential, long-time editor of DC’s Vertigo line] Karen Berger departing did get me thinking. I’m really interested in the story of DC in the 1980s especially, but I spent a lot of my life thinking about Marvel Comics in particular.

Related: Adjusted For Inflation: How Much More Do Comic Books Cost Today? and Batman-ish: What Comic Book Movies Are Missing

New York City, December 17, 2012

[No stars] Lightless again; damp, dull, and chill. A cold headwind gathered strength with each step away from home. Sparrows hopped around the A-C/B-D platform at Columbus Circle, two levels down from the out-of-doors. A no-passengers train, interior darkened, rolled through the station. Down by Lafayette Street, around a corner, people surrounded a young woman who lay huddled on a sheet of cardboard. One of them bent over her solicitously and rearranged some scattered matchbooks, a tableau of fake suffering, as another stepped back with a camera. Now and then the wind carried tiny flecks of drizzle, so small they barely registered as wet, but as pinpricks of a colder cold. In the fading afternoon, someone in the next apartment building was shooting flash photographs in a room with the lights off — a nagging, intermittent stimulus to the peripheral vision, which was otherwise ready to quit for the day.

"For Little Kids"

“Basically, there’s three models. A SwissGear that’s made for teens, and we’ve got an Avengers and a Disney Princess backpack for little kids.”

Here I Am, Rock You Like A Fish Tornado

“I have been trying to capture this image ever since I saw the behavior of these fish and witnessed the incredible tornado that they form during courtship.”

— Sadly, marine biologist Octavio Aburto neglected to soundtrack the video he made of jackfish engaged in group mating behavior called “aggregation.” (Hey, Jackfish are just like bloggers!) I would have gone with the Scorps. Or Dead or Alive (natch.)

Newspaper Article From 1694 Misreporting Activities Of Heathen Chinese Emperor Holds Important...

Newspaper Article From 1694 Misreporting Activities Of Heathen Chinese Emperor Holds Important Lessons For Twitter, Breaking News, Etc.

“[T]he reporter announces ‘no considerable News, except that the Emperor of China, his Court, and a great Part of his Kingdom have embraced the Christian Religion; but this is too extraordinary to be believed without farther Confirmation.’ It got me thinking about the media conversation in the wake of the Newtown shooting — about how, like during so many breaking stories, reporters were too quick to report details that turned out to be incorrect.”

The Awesome Treasures of Anthony Braxton's Music Club

by Seth Colter Walls

A series on the stuff that delighted us on the Internet this year.

There was something atypical and fun in Monday’s New York Times: a review of a concert that happened over the weekend in… Washington, D.C. Staff critic Acela-hopping to the latest jam at the Kennedy Center is not common, as Times critics have all they can cover here in town, usually.

But the reason for last weekend’s exception was plenty good, as recent MacArthur Award winning pianist Jason Moran had invited the great (and also MacArthur-winning) avant-music legend Anthony Braxton to present a band that included Braxton’s former student, the guitarist (and Awl favorite) Mary Halvorson.

Take us there, Ben Ratliff!

Why not Braxton at the Kennedy Center? Abstraction at the institution! Anarchist on the Potomac! Also, and more seriously, music without much practical connection to swing rhythm and the blues, presented under the banner of jazz. Many knew in a general sense what they were coming for. Mr. Braxton, 67, is an American musical force with hundreds of records. But the Kennedy Center is a subscriber-based institution, patronized partly by those who might not follow jazz beyond the institution’s mailings. And so, by Minute 5 or 6 of a 75-minute performance, the grumbling began, robust and aggrieved, from those who thought they were going to hear something similar to what they knew.

“What does it mean?” I heard it behind me. Forceful exhaling too. Soon walkouts. All good and healthy.

Ratliff is correct that a concert strong enough to produce walkouts is a good and healthy thing. (It’s worth noting that even New York has its more upsettable concert-goers, as I saw recently during a blistering Wozzeck conducted by Esa-Pekka Salonen at Avery Fisher Hall.) And yet there was, as it happens, a perfectly good answer to the question of “what does it mean,” and it comes from Braxton himself: “I know I’m an African-American, and I know I play the saxophone, but I’m not a jazz musician. I’m not a classical musician, either. My music is like my life: It’s in between these areas.”

This comes from the bio on Braxton’s own website, which is its own good and healthy thing — helping as it does to make people aware of the meaning of a work before they surprise-surprise bump into the new radical music as part of a subscribers’-folly ticket package. Because Braxton has gone the self-distribution route online, it is now easier than previously (as a practical matter) to get to know his music. If you are bored of your Internet, perhaps give Anthony’s a look — or even join. Even at the price-point of zero dollars, it boasts many treasures.

His “Tri-Centric Foundation” (the name comes from a Braxton’s own multi-hundred page philosophical-music text) was established a couple years back, in order to revamp a prior self-distributed label that had shuttered.

Now, instead of pressing costly CDs, most of Braxton’s new albums are just distributed as mp3s (or FLAC files, if you’re like that) to subscribers.

This is a worthy and notable development, if only because it helps fans to keep up with Braxton’s many projects and performances (over nearly half a century) without carting a bunch of physical media everywhere one winds up living, the way one lives now. This month, subscribers have heard a recording by a current Braxton band — “Echo Echo Mirror House” — in which players, aside from their instruments, play Braxton’s old pieces loaded onto iPods.

We also, just this morning, received a nice bonus holiday gift: a long-lost solo performance by Braxton at Carnegie Hall’s recital space, now dubbed the Weill Recital Hall. (If you subscribe this month, you can still get both of these albums as your “monthly” free download.)

That performance was previously undocumented. After the 38-minute tape was discovered as part of a bootlegger’s trove earlier this year, the music was sent to Braxton’s foundation, and then prepared for its released today (along with the image below of the bootlegger’s very hip sunglasses-and-microphones setup).

Photo: Kyoko Kitamura

It’s a real treat, this solo Carnegie performance from 1972! I’m still getting used to how bluesily expressive the first improvisation and the run through “Lush Life” sound.

There are, to be sure, more experimental textures involved. According to the Tri-Centric Foundation, the only previous record of this Braxton date appeared in a brief Times listing, though the concert itself was not reviewed. However, just a few weeks before the Carnegie performance, the paper’s John S. Wilson wrote on another early Braxton performance at Town Hall; he called Braxton “very capable as a jazz alto-saxophonist” in the context of Chick Corea’s then-current band, and also handy with the theme of “All the Things You Are” — at least before the musician indulged what Wilson termed “the ridiculousness of gasping shrieks and squeals.”

And so we find that the question of “what does it mean” has long been with us. That Braxton can still force 48 walkouts at the Kennedy Center on a single night was of some interest to Washington City Paper’s Michael J. West: “There’s a lot to take away from this,” West wrote. “For one, that Braxton after almost 50 years still has the power to provoke. For another, that Washington D.C. in the Obama era remains a conservative place.”

And so the work continues. Of the 12 more-contemporary recordings that the Tri-Centric Foundation released this year to monthly subscribers, two count (to my mind) as very important additions to the Braxton discography: a choral album and a large improvising-orchestra session, both recorded in 2011.

Here is a clip of the wonderfully loopy choral piece:

And here’s what Braxton is up to with a big band these days (one that also includes Awl favorite Steve Lehman):

Let us take a moment to appreciate the fact that many musicians who try to run monthly subscription services often run out of monthly ideas. For example: there was a fun period, running from the late 90s up until about 2002 or so, when it was very much worth it to pay a flat fee in order to hear how Prince was entertaining himself in the studio every few weeks. Then his storied songwriting productivity sorta fell off, and you spent your time in the Prince-internet figuring out how to play Windows Media files loaded with DRM that had been stashed in a bad video game version of Clue. (Oh I see: the Purple One hid the Jimi Hendrix-style guitar freakout in the study underneath the desk with a candle on it.) At this point, it was safe to “unsubscribe” from his service and just wait for an album every other year (until those stopped coming, also).

By way of contrast, it is fair to say that one thing Anthony Braxton has never been out of is ideas — either on paper or live in performance — making him exactly the sort of artist that merits month-to-month attention. Ever since Braxton joined up with the Association for the Advancement of Creative Musicians in their late-60s, South Side Chicago firmament, the multi-reed-playing composer has been a force for ingenuity. He expanded the language of saxophone in jazz music, played with giants of international improvisation like Derek Bailey and more canonized folk such as the late Dave Brubeck, and has written a cycle of tremendous (and idiosyncratic) operas. And for the last couple years, he’s had this really exciting website.

Even if you are not ready to spend $7.99 a month to get whatever new album Braxton approves for release (plus a 30% discount on all back-catalog downloads), there are, at any one time, 13 different bootlegs you can download for free over there. (Every time the foundation makes a new batch of 13 downloads available for “friendly experiencers,” the previous set of 13 bootlegs goes behind the subscriber paywall.)

The current range of 13 official bootlegs finds Braxton in many interesting ensembles dating from the 70s and 80s. Here’s a hot quintet performance with Kenny Wheeler on trumpet, Dave Holland on bass, Richard Teitelbaum on syntheszier and Barry Altschul on drums, in which the ensemble has a wonderfully un-busy way with the jagged theme of Braxton’s “Composition No. 23G.” Then the leader hops in, moving at light-speed, with added pieces of synth shrapnel bits adding to the fun in the background. Even farther out is this 1982 trio date with free improv guitarist Derek Bailey and the trombonist-composer George Lewis. And one of Braxton’s fine mid-80s quartets with Marilyn Crispell on piano — the site of some of Braxton’s most recognizably “jazz”-y work — is represented on this free-to-have recording.

If you listen to those three bootlegs and want to hear more: oh boy, is there ever more. Most important, at least in terms of “music history as it stands so far,” are the nine LPs that Braxton cut for the insanely well-funded Arista label in the 1970s. They were finally collected on CD for this box set, which is money very well spent — though it is an all-at-once sort of investment.

So perhaps you’d just like to be surprised by the monthly Braxton download, thereby keeping very up to the minute with one of the world’s most surprising musicians. As for last weekend’s performance down in Washington, there’s every reason to hope it’ll be one of the foundation’s albums released in 2013. (That is unless Jason Moran’s label pulls some kind of proprietary nonsense on us. So, uh: Blue Note, please don’t do that.) The Washington Post, which devoted less than half as much space to Braxton’s performance as The Times, cited with approval the “animalistic roars, delicate filigrees, sudden driving attacks, breathy fragments of melody, amplified scratches.” Maybe now that Braxton’s foundation has an organized way of preserving these performances for posterity, even last weekend’s mutterers and early-leavers will have some future opportunity to come around to those, and other, sounds.

Previously in series: Not OK Cupid

Seth Colter Walls is a culture critic and reporter for Slate, NewYorker.com, The Village Voice, Washington Post, Capital New York, and lots of other places.