Live Like You've Already Died and You're Just Watching Your Relatives Masturbate

And other answers to questions you didn’t ask.

“What do you think happens after we die?” — Alfred Afraid

We’re probably forced to watch re-runs of our own lives in an empty classroom on an old-fashioned TV with antennae and tin foil. We see all the mistakes we made played out over and over again. After a while it gets really funny. We will think to ourselves, “I’m still really happy I completely thwarted that relationship.” This goes on and on forever. It is kind of like those rubber rooms they send teachers too when they’ve freaked out on a kid. They wait forever to be fired thinking “Is today the day?” Except today is never the day. You just keep waking up. You just keep getting to screw around with your phone.

I’m still not completely convinced that most dead people aren’t just hiding. That makes way more sense. The idea that everybody automatically dies at the end of their life is kind of crazy and boring at the same time. I know that Mary, Jesus’s mother, was assumed into heaven. Like heaven sent down an invisible elevator and just kind of let her go all the way to the top floor without passing Go or collecting $200. Maybe more people get that kind of treatment? Like quiet people no one really knows who haven’t bothered anybody? They just get sent directly all the way to the top floor?

I understand why some people do die. You just would never be able to shut them up otherwise. No one would ever get a word in edgewise. Imagine a room filled with all the biggest male egos ever invented, all of them insistently mansplaining at the top of their lungs all the time. No one would want to listen to that podcast. Hitler, Mao, The Joker from Batman, Stalin, Trump, Robin Williams, Darth Vader, that “Yo Quiero” dog from the Taco Bell commercials. All of them constantly yapping, blah blah blah. You’d yearn for death to take you away to a quiet, dark, endlessly paralyzing cave of nothingness.

Life is hard. Plagues, war, famine, bad episodes of ‘Twin Peaks.” We humans have endured them all. My pants are way over there, so I’ve been walking around my apartment naked all day. It’s been quite an ordeal. It does not make me yearn for the milky silence death must provide. I fear death like I fear success. Any change in the status quo means certain doom. Probably. I may never find out. This cool guy Justin I once knew from one of the bookstores I worked at had a tattoo that said “Fail Better.” That is possibly a Beckett quote? Or a William Gaddis one? Or your mom said it, I can’t remember. Memory is the first to go on the way to being dead. And it’s kind of a relief. Remembering everything all the time is such a burden. I want to get a tattoo that says “Fail Worse.” But tattoos are hard for me; I get so fainty. And they hurt!

If people are dissatisfied with what comes after death, we’re hearing very few complaints. Most of them come from little children who have died and come back and write books about the experience. They generally follow an irresistible light to a wonderful place in which joy is palpable like the humid noontime air. And for some reason because they miss their dog or something they turn back. They watch themselves in the hospital room from high above. Then they come back, write a book, make millions and someday probably wish they’d stayed in the light. Humans are not built for comfort and success. We yearn for struggle. To rise and fall. And resist forever all the things we should jump directly into. Like gluten. We should be so filled with gluten all the time. Oh, well.

Many people use death as a simmering warning. People want to accomplish X, Y and Z before they croak. But death comes whenever, either too early or too late, and signifies very little. If someone did construct this reality, they must not have been very good at writing endings. Endings are hard to write. Not as hard as titles, but pretty hard. A writer just keeps thinking the next best line might just be around the corner. And then the next corner. And then we run out of corners.

Most people would rather die than have to give a speech in public. That seems weird. No one really listens to speeches all that much. And if speeches are short no one gets all that bothered. Dying, on the other hand, seems pretty permanent. I guess it’s possible that some people know they’re on their second or third trip through the human sausage maker. You’d think they’d know what’s going on.

If no one knows what happens after we die, and no dead people are complaining all that loudly, I guess we will just have to be patient and wait to find out. I hope it’s like the movie Wings of Desire where I become an angel and watch people in libraries all day. And maybe get to meet Peter Falk. I fell asleep during that movie. But it looked good in black and white. And I like those long winter coats. But even lying perfectly still under ground without breathing might be fun for a while. I’ll be dead a long time. The thing that worries me the most is missing new episodes of ‘Twin Peaks.’ Which will most likely be awful. But I’m alive and you’ve got to spend the time doing something.

We shouldn’t worry about death. But we all will. Like I irrationally worry about my penis just suddenly falling off and rolling around in the middle of the street. I worry about this a lot. There’s nothing you can do. Either your penis will fall off for no reason in the street or it won’t. Either we all die or we’re just really good at hiding. Only time will tell. Or you can buy me a bunch of beers and I’ll draw it out for you on a napkin. Either way, don’t worry. Worrying is worse than dying.

Jim Behrle lives in Jersey City, NJ and works in a bookstore.

Earth, Approximately

Notes on life

Liana Finck’s cartoons appear in The New Yorker and on Catapult. She posts her drawings on Instagram.

Arbor Day Is The Only Holiday That Matters. Period.

Arbor Day Is The Best Holiday

Period.

“Trees were so rare in that country … that we used to feel anxious about them, and visit them as if they were persons.”

Something about that line from Willa Cather’s My Ántonia stopped me cold when I first encountered it years ago. I was young then, a teenager, and the novel was unlike anything I’d read before; I didn’t quite understand why the book had such an effect on me. (Mencken hit it on the head when he declared unequivocally, “no romantic novel ever written in America … is one half so beautiful as My Ántonia.”) The notion of people checking in on trees, making sure they were all right, was so foreign to my own experience — growing up in the arboreal Northeast — and so endearing that it never really left me. Now, in late April of this uneasy year, after a sketchy early spring that felt like the seasonal equivalent of a flu patient’s thready pulse — perceptible, but just barely — I’m thinking again of Cather’s book and the companionable nature of trees, because the only holiday that matters is here again: Arbor Day.

Believe me, I have no interest in pitting holidays against each other, and not only because any such contest will be over before it even begins if Arbor Day is in the mix. But if we are going to compare holidays…well, with due respect to secular and religious rites everywhere, they all come up short against a day set aside to celebrate trees.

Of course, billions of people around the world get their knickers in a twist (in the best and worst possible ways) over holidays of all kinds, from Hanukkah, Eid al-Adha, Christmas, Kwaanza and Rama Navami to Halloween, Guy Fawkes Night, St. Patrick’s Day and more. But for everyone who feels love for one of those holidays, there’s usually someone else who actively dislikes it. Untold numbers of people despise Christmas because all they see is the schlocky, turgid consumerism that has come to define it. Many rational, live-and-let-live men and women would be perfectly happy if Halloween was abolished forever. Millions can’t stand Thanksgiving, because obligatory family get-togethers suck and/or turkeycide.

And then there’s Arbor Day, a holiday so straightforward and unencumbered by politics, sectarian twaddle or historical grievances that each year it feels somehow radically innocent in a way that, say, poor old Columbus Day never can. It’s a day to “celebrate the role of trees in our lives” and “to promote tree planting and care.” Period. Arbor Day is not trying to be something more than what it already is: elemental. If it was a geometric shape, it would be a circle. If it was a rock and roll record, it would be the Velvet Underground’s first album.

In January 1872, a man named J. Sterling Morton, a Detroit native and one-time secretary of the Nebraska Territory, proposed a tree-planting holiday, “Arbor Day,” at a meeting of Nebraska’s State Board of Agriculture. Trees, Morton knew, were badly needed in that part of the country as windbreaks, as means for keeping the land’s rich soil in place, for fuel and building materials, and for shade from the broiling sun that so often hammered away at the Great Plains. A few months later, on the first Arbor Day — April 10, 1872 — more than a million trees were planted across Nebraska. The perfect holiday was born. (A small village in northern Spain, Mondoñedo, is credited as the site of the first official, municipal tree-planting festival or holiday in the world, in 1594.)

Today, Arbor Day is celebrated in every state in the U.S. and in some form or other in scores of countries around the world. Just last year, Madagascar celebrated its first-ever official Arbor Day, a few years after it began planting hundreds of thousands of trees annually with help from the Nebraska-based Arbor Day Foundation, to help the famously eco-diverse island nation recover from decades of aggressive deforestation. Individual U.S. states set aside their own days for local ceremonies, based on planting seasons and other regional factors. Arbor Day in Hawaii and Texas, for example, falls on the first Friday in November. In Louisiana, it’s the third Friday in January. In Alaska, the third Monday in May, and so on. But the national Arbor Day in the U.S. is always celebrated on the last Friday in April.

Whenever people choose to mark the day, though, it is the holiday’s immediately graspable core sentiment and mission — Trees are good. Let’s plant lots of them — that lend Arbor Day its forthright, somehow very Nebraskan vibe. Yes, trees are beautiful. No one denies it. But trees also work, damn it. They keep city streets cool in the summer. They provide habitat for an infinite variety of critters. They release oxygen. They absorb carbon dioxide. They help prevent flooding. They hold hammocks and swings. No other living things are simultaneously as utilitarian and as aesthetically inspiring as trees. They get the job done, and they look good doing it.

For Dan Lambe, the 46-year-old president of the Arbor Day Foundation, the holiday is in his blood. A native Nebraskan, Lambe grew up in Lincoln and as a child went with his family “every fall to pick apples and drink cider from the orchards in Nebraska City, the home of Arbor Day.” Lambe left Nebraska for a while and worked for non-profits in California, Arizona, and Texas. He moved back to Lincoln a decade ago, jumping at the chance to return home and work for the Arbor Day Foundation (founded in 1972). He was named president in 2014.

Lambe’s laughter is boyish. There’s no other way to describe it. He sounds like a kid. “I’ll tell you,” he says, “to work every year toward a holiday as positive and as inspiring as Arbor Day is as awesome as it sounds. Planting trees is not the most complicated thing in the world, but for future generations, the benefits of planting even one tree are immense.”

In the four decades the foundation has been around, it has helped towns and cities plant more than 250 million trees. Factor in that a single tree can absorb almost 50 pounds of carbon dioxide every year, and can sequester around a ton of carbon dioxide by the time it reaches 40 years old, and the benefits of a quarter-billion trees are immense, indeed.

Arbor Day is not about nationalism, or religious dogma, or some vaguely tribal ethnic pride. Instead, it’s a holiday steeped in optimism. It’s a holiday that deepens a notion of stewardship and renewal of the natural world, rather than ownership and exploitation. It’s a holiday that makes us think about the sort of world we want to leave to our kids and grandkids. J. Sterling Morton himself argued that his brainchild “is not like other holidays. Each of those reposes on the past, while Arbor Day proposes for the future.” Amen to that.

New York City, April 27, 2017

★★ Indoors was stuffy but the air outside was too thick for its coolness to be any relief. The kindergarteners traipsed out into the gray in their double lines, on assignment to notice things on a loop around the neighborhood. They noticed trash cans and trucks and phone booths, and they noticed when now and then the still-heavy clouds released some drizzle. Their noticing did not rise to the level of complaint, though. Sun was shining on the white tile walls of the stairs at Union Square, and people were casting shadows. The clouds and sun went back and forth; brightness took over a stretch of afternoon, like an underdog basketball team using up its legs in a third-quarter surge, before the gloom claimed its inescapable victory.

Roman Flügel, "People and Places"

I can’t get started

I’m sorry, I’m just not ready for this week yet. I am still feeling beat up from last week. I don’t even know what to do. Here’s a picture of a dog and some new music from Roman Flügel that will hopefully keep you amused while I figure it out. Enjoy.

Incorrigible Sin

The story of a seventeenth-century fornication trial in Massachusetts Bay

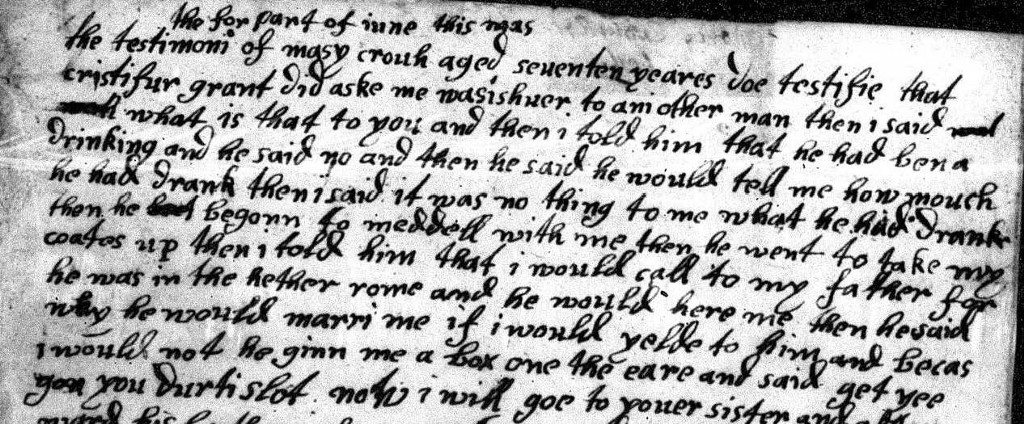

One of the worst nights of Sarah Crouch’s life began with an innocent request. Her mother asked her to go out into the fields and fetch Thomas Jones for supper. It was a quiet June evening during the pea harvest of 1668, and the sun had just begun to set over the Crouch family’s homestead in Charlestown, Massachusetts. Though Crouch, 20, had just woken from an early-evening nap, she gladly agreed to wrangle him in. Jones, who worked for her father, was a common presence in their household. Crouch liked him. As to how well, it depended on whom one asked.

Charlestown’s lively gossip mill buzzed with rumors of the couple’s intimacy — likely based upon the claim made by the Crouches’ neighbors, Joseph Bacheler and Paul Wilson, that they had seen Crouch in bed with Jones at the home of Theophilus Marches during the “last election day at Boston.” Another rumor claimed that Crouch and the twenty-three-year-old bricklayer were not only intimate but also secretly engaged.

This latter rumor was of particular interest to another regular visitor to the Crouch homestead: Middlesex County’s own resident Lothario, Christopher Grant, Jr. Crouch knew Grant, 24, through mutual friends. That same evening, he and his brother, Joshua, had dropped by for an unannounced visit. As Crouch made her way outside to find Jones, Christopher rushed toward Crouch’s mother. “Might I go forth with her,” he asked; to which she responded, “As long as you stay within hearing.”

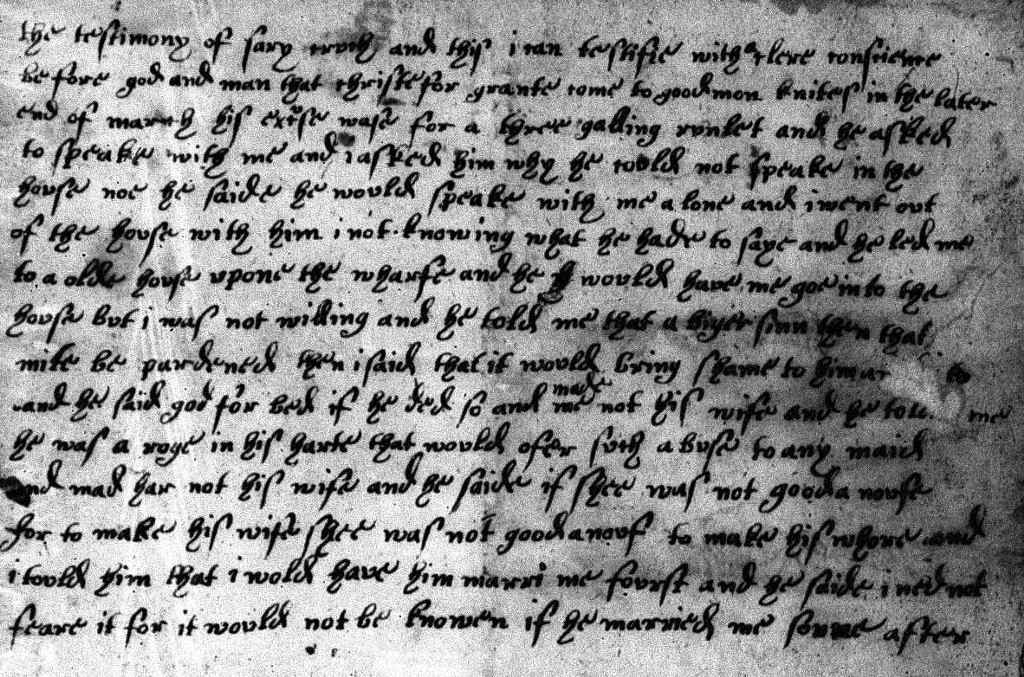

Crouch’s account of the evening, written one year later as a court deposition, does not reveal her thoughts on Grant’s insistence, nor does it explain the excuse he had given to her parents to explain his presence at their house that evening. It is very likely, however, that she knew Grant’s intentions. In her own words, he had “made use” of her body at least twice over the past few months. The first of these encounters occurred on March 28 in “an olde house upon the wharfe.” There, Grant seduced her with a Falstaffian marriage proposal. “If she was not good enough to make her his wife she was not good enough to make his whore,” he said. When Sarah responded that they should wait, “he said I need not fear for it would not be known if he married me soon after.” Amid a second sexual encounter in April, Crouch had told Grant that she feared the first had resulted in a pregnancy. “How long afore [you’ve] had the sines of a maid,” Grant asked her. “Three days before the first time [you’d] had to do with me,” she responded.

Grant, desiring either sex or updates on her condition, and angered by the unconfirmed rumor of her engagement to Jones, kept close to her in the months to follow. This June night would prove no different. Sarah soon trekked out into her father’s fields to search for her rumored fiancée, trailed by the “heartless rogue” who may have gotten her pregnant.

In the mid-seventeenth century, Massachusetts Bay found itself amid a spiritual identity crisis. Many first- and second-generation settlers believed their children and grandchildren had lost touch with the colony’s original mission. This new generation was materialistic and greedy. Worse, it was becoming increasingly sexual. Though pregnancies out of wedlock were far rarer in Massachusetts Bay than in England or its other colonies, records show that by 1665, County Court officials saw premarital sex as “a shameful Sin, much increasing amongst us.”

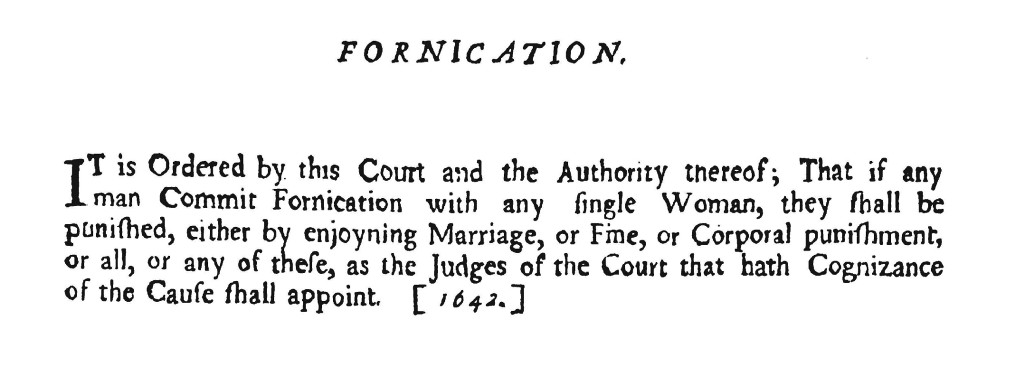

Contrary to modern perception, Puritans were not ashamed of sex itself. As the historian Edmund Morgan put it, the New England Clergy, “the most Puritanical of the Puritans,” believed that so long as a healthy sex life did not interfere with a married couple’s relationship with God, they were welcome, and indeed encouraged, to discuss and explore its boundaries. Premarital sex, however, remained illegal. Massachusetts’ first published fornication law, written in 1642, stated that guilty parties should be “punished, either by enjoyning Marriage, or Fine, or [whipping].” Two decades later, they added excommunication to the list. When caught in the act, or when exposed through pregnancy, “fornicators” were indicted and scheduled to appear before a group of magistrates during one of four annual meetings of a local county court. The historian Roger Thompson reports roughly 125 of these trials occurred between 1649 and 1680. Most were cut and dry. The accused mother, if pregnant, named a father. Magistrates then doled out punishments and made provisions for the resultant child.

Cases involving disputed paternity were far more complicated. Such was the case with Sarah Crouch and Christopher Grant Jr. The Crouch v. Grant case file, found in Folio 52 of the Middlesex County Court Records, contains 26 documents. Dated Feb. 2, 1669, these papers — which recount everything from rape allegations to a late-night orgy — tell the story of a love triangle involving the exact sort of rebellious twenty-somethings whom elderly colonists resented. Crouch came from subversive stock. One year earlier, the Charlestown Church had formally censured her father for “the scandalous sin of Drunkness” and his “not manifesting repentance for it.” Grant too came from a controversial family. Before his own indictment for fornication, the Court had already convicted two of his sisters for the same crime.

Colonial courts relied heavily upon written depositions. Defendants and witnesses prepared these documents in the months before proceedings began. Shortly after her indictment, Crouch could expect everyone she knew — her family, her neighbors, her enemies — to commit to paper their private thoughts about her, her reputation, and her behavior. Through these accounts, one can begin to imagine what it must have felt like to be young, libidinous, and malcontented while living in seventeenth-century New England.

Like thousands of other ordinary colonists, most of Sarah Crouch’s life exists within an elementary outline culled from official records: birth, baptism, marriage, death. Church logs suggest she was strong-willed and impetuous. Officials lamented that at the time of her indictment, Crouch was not “in full communion.” Although she had been baptized as an infant, she had yet to fully devote herself to the Church, nor had she shown any desire to do so.

Still, as Crouch went to trial, she had support. Depositions written in her defense — principally those by Thomas Jones and her sister, Mary — suggest a coordinated effort. As colonial courts only met four times a year, she and her friends had months to get their stories straight. Crouch’s pregnancy made it impossible to deny guilt. She therefore devoted her efforts to proving Grant, rather than Thomas Jones, had fathered her child. She and her peers focused on the man’s persistent and at times violent history with women. Crouch’s sister suggested he had once propositioned her by promising to marry her if she had consented to sex. When she refused, Grant had attempted to “meddell” with her, allegedly taking her “coates up,” boxing one of her ears, and calling her a “dirty slot.”

Though it had been the first of two consensual encounters that had resulted in pregnancy, Crouch committed the bulk of her testimony to a third and comparably violent run-in with Grant: the night he followed her into her father’s fields to find Jones. According to Crouch, he immediately revealed himself as a jealous mess. The rumor about her engagement to Jones — which she never confirmed in her own testimony — had sent him into a fury. One witness claimed that a few weeks earlier, Grant had been so worked up over it that he confronted Sarah’s father, who confessed ignorance. That night in June, Grant’s frustration boiled over.

“I have more right to you than he does,” Grant told Crouch. “[Jones] can maintenance you about as well as a dirt dauber.”

Crouch testified that things soon turned violent. “He took me by my [two] hands,” she wrote, “[and pulled] me along and under the fence.” There, Grant allegedly raped her.

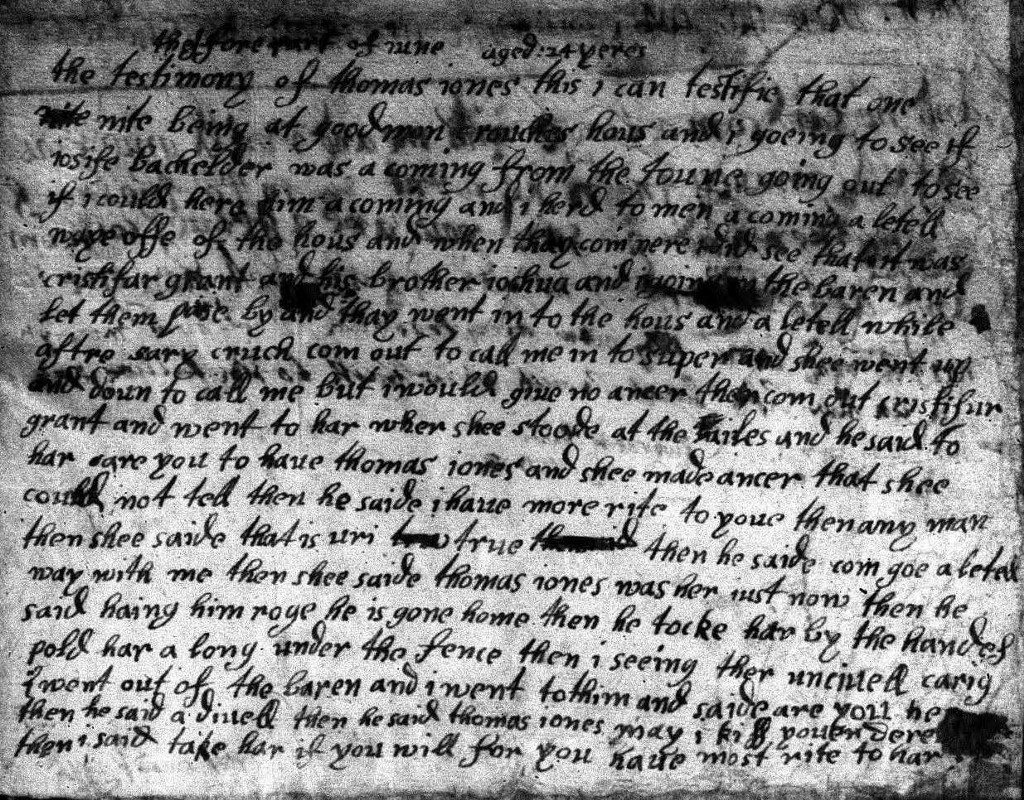

At some point, the pair was interrupted by none other than Thomas Jones. He had been hiding in a barn within eye and earshot of the whole affair. Per his own brief testimony — a deposition that mimicked Crouch’s nearly to the word — he had been searching for a friend earlier that evening when he had heard the Grant brothers enter the Crouch family property. By the time Crouch had begun to call for him, he had already taken his place in the barn. It is not clear whether Jones knew of Crouch’s history with Grant. Regardless, he had seen enough.

“Henceforth,” Jones told Crouch, “I will have nothing to say to you anymore.”

Grant took the opportunity to rub salt in Jones’ wound.

“Shall I kiss your garle, Thomas?”

“You have more right to her than I have,” Jones replied. “Take her if you will.”

What happened next eludes the historical record. The story picks up a few weeks later when Crouch confirmed to Grant she was indeed pregnant. She claimed that they spent the next few weeks weighing their options. Finally, Grant put his foot down. He told her he would only marry her if she ended the pregnancy. Crouch refused, and Grant failed to propose.

Heading into trial, Grant faced an uphill battle. The burden of proof in Puritan paternity cases typically fell on would-be fathers. Most magistrates reasoned it was a greater sin to force an infant and its mother into pecuniary uncertainty than it was to compel a man to financially support someone else’s child. Defendants needed to provide overwhelming exculpatory evidence, otherwise the Court would deem the accused legally responsible “notwithstanding his denial.”

Grant put together a much better case than most. Numerous friends, neighbors, and family members wrote depositions in his defense. Just as Crouch and Jones seem to have straightened their stories before committing them to paper, it is clear Grant conducted his own private investigation into what, exactly, people were saying about the events leading up to Sarah’s pregnancy. In his testimony, he urged the magistrates to pay close attention to the depositions written by his brothers; another one penned by a man named Samuel Church; and, especially, the testimony of a woman named Sarah Largin.

These documents tell a radically different story from the one narrated by Crouch and Jones. Not only did Grant deny any intimacy with Crouch, but he and his supporters also hinted at conspiracy. Grant’s brother, Joseph, testified that Crouch was obsessed with Christopher, who “gave her no cause to love him.” Even more pointedly, Church implied that Crouch knew she was pregnant and chose to pin the paternity on Grant because he was “rich at the time” and thereby better suited to support her child than was Thomas Jones (presumably the true father).

Charlestown resident Ursula Cole claimed that shortly after Crouch’s pregnancy became public knowledge, Jones had described to her a recent encounter with Crouch, in which she implied Jones was the father. “[Jones] told [Crouch] that she showeth as if she [was] bigg with childe,” Cole wrote, “and [Crouch] answered [if I am with child] you shall provide blanketts for it.” Jones then allegedly assured Crouch if she were pregnant with his baby, he would do his part to support the child. Cole added that Jones even bought her a symbolic blanket. By July of 1668 — one month after the confrontation outside the Crouch home — Cole had heard that the couple had split up. She said Crouch told her that Jones had dumped her because he was “jealous of Christopher Grant,” even though “he had no occasion at all” to feel threatened.

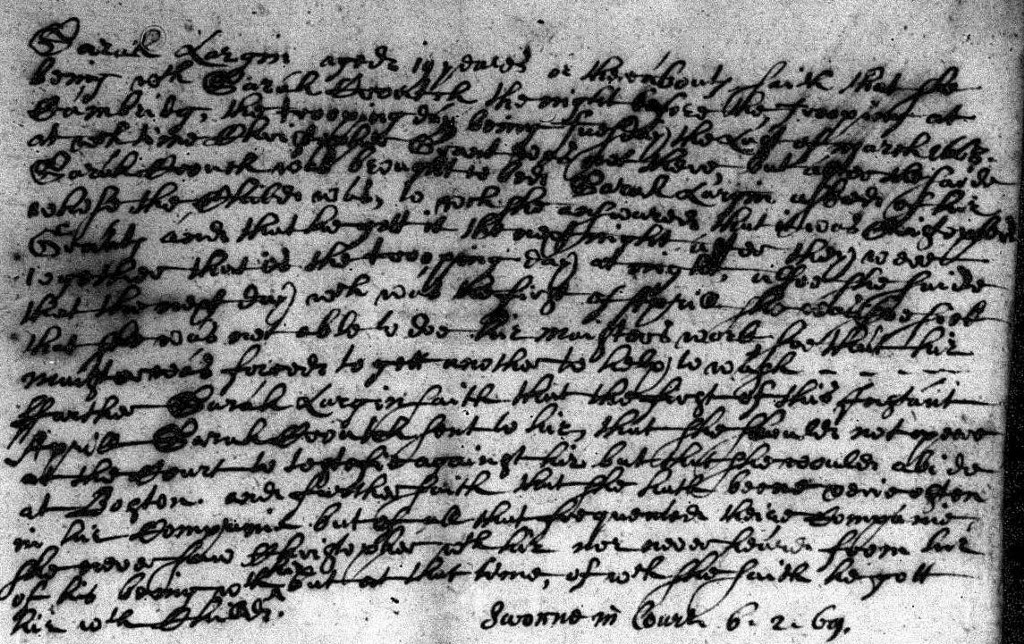

Largin claimed she was with Crouch during the alleged night of conception “at which time Christopher was not there.” Months later, when Largin noticed Crouch’s belly, she asked her about the identity of the father. Crouch quickly named Grant. Soon thereafter, Largin confronted her on the inconsistencies. Crouch’s response to this confrontation remains lost, but she clearly panicked. According to Largin, a few weeks before trial, Crouch “sent to her that she should not appear at Court to testify against her but that she should abide at Boston.” Largin concluded her deposition by admitting that although she had seen Crouch “very often” in Grant’s company, “she never saw Christopher with her [around the time] she saith he got her with child.”

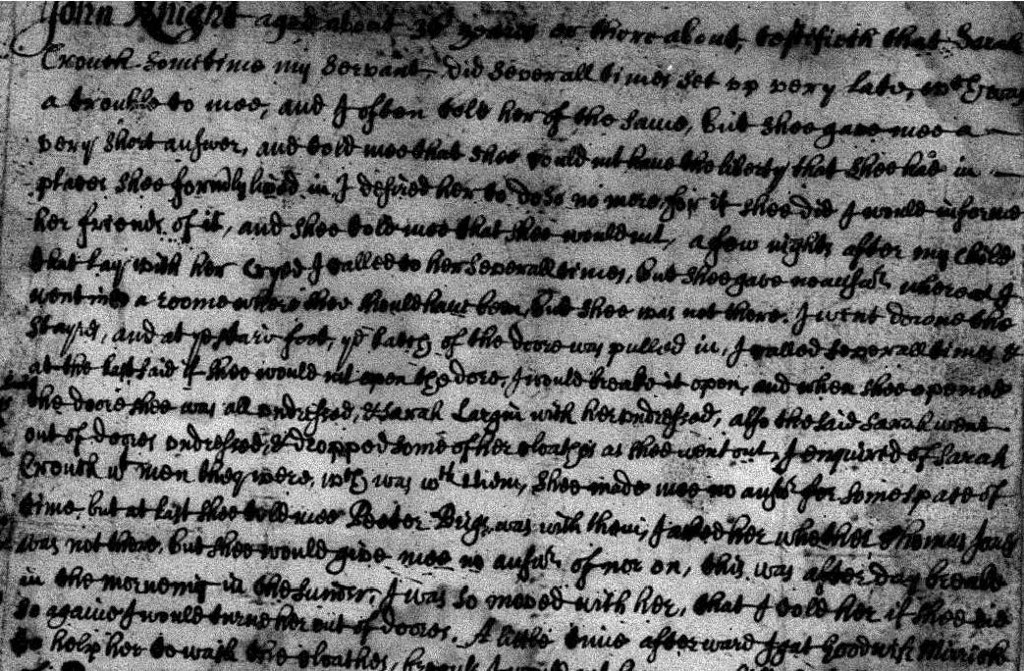

Largin’s testimony carried a great deal of weight, not only because she was close to both parties, but because she herself had been implicated in salacious rumors about Crouch. Few in Massachusetts knew more about her sex life. Nowhere was this more evident than in the provocative testimony of Crouch’s employer, John Knight.

Knight, a widower with multiple young children, made his living building and repairing barrels in nearby Watertown. He employed a handful of part-time servants and maids, and his testimony suggests Crouch often took care of Knight’s infant as the cooper slept. This work left Crouch unsupervised in late evenings and early mornings, of which Knight claimed she took full advantage. “My servant did severall times stay up veri late [causing trouble] to mee,” he wrote in his deposition. “I Often told her of the same, but she gave me a veri short answer and told me that she would not [give up] the liberty that she [had] in places she formally lived in.”

One evening, he awoke to the sound of his child bawling. He called to Crouch several times, “but she gave no answer.” Vexed, Knight meandered sleepily into his child’s room only to find the baby unattended. Crouch’s quarters were empty, but he soon heard a series of noises coming from a room or a closet near the stairwell. Assuming Crouch was inside, he yelled “that if Shee would not open the door, [he] would break it open.” The doors unlatched, and out came “[Sarah Crouch] all undressed [and] Sarah Largin with her undressed.” Largin took off through the front door, dropping “some of her clothes as she went out.” Knight cornered Crouch and inquired about any men who might have been in her company before his arrival. “She made mee no answer for some span of time,” he wrote, “but at last Shee told me Peter Brigs [another local twenty-something] was with them.” Apparently aware of Crouch’s involvement with Thomas Jones, Knight asked if “Jones was not there” as well. When Crouch failed to respond, he became “so mad with her” he threatened to “turn her out of doors.”

A few days later, the cooper hired an extra servant — a woman named Goody Mirrick — to help him with his laundry. He left Mirrick and Crouch alone as he ran an errand in town. When he returned that afternoon, he found Mirrick “alone and the childe crying.” He asked her where his “maid was.” Mirrick, begging forgiveness, answered that Crouch was not in the house. Knight searched his property, and again came upon a closed door latched shut, behind which he found Crouch and Largin in a state of undress, this time with Brigs and another local man named Michael Tandy.

Knight’s story supported two major facets of Grant’s defense. First, it confirmed Crouch was sexually adventurous. Second, it demonstrated her relationship with Jones had become so well known in Charlestown that even Knight, a grown man with no direct ties to her peer group, knew to ask if Jones were involved in the closet orgy. This, along with Crouch’s neighbors’ testimony that they had caught her in bed with Jones shortly before her pregnancy, greatly complicated the paternity issue. Was this unflattering (but largely hearsay) testimony enough to earn Grant a rare and unlikely acquittal?

Colonial court records are cruel to curious readers. Their depositions resemble proper narratives, as they recount interesting events from multiple points of view, often richly and in great detail. Yet these records aren’t narratives, nor are they inherently rooted in the truth. They gleefully rebuff Chekov’s gun. They heighten anticipation through made-for-cinema twists and turns, without a single guarantee of a satisfying resolution.

The Crouch vs. Grant case file contains no record of a final judgment from Court magistrates, but subsequent Middlesex County Court files shed light on the result. On April 15, 1669, Grant’s parents wrote a letter to the Court that implied the trial had ended in his conviction. In it, they lamented that their son was “Sentenced to the house of corrections.” But he never actually made it there. At some point between the trial and their petition, “[Grant] maid his Escape.” Court magistrates had also sentenced Christopher to a public whipping. According to his parents, the prospect of this punishment had caused him to flee town.

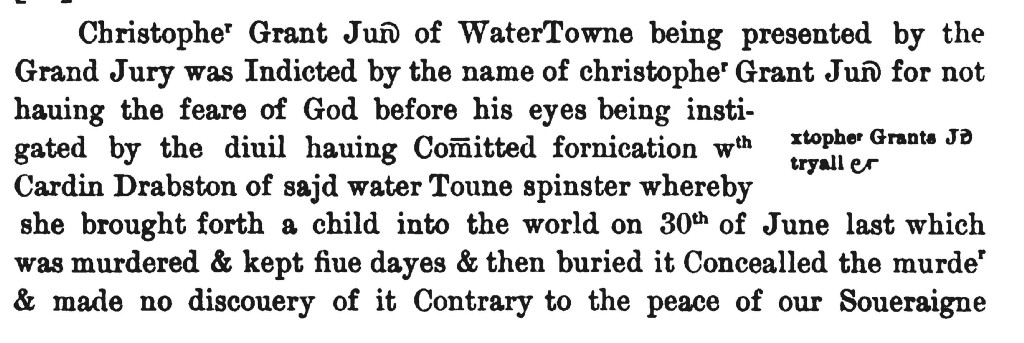

By 1677, records show Grant was back in Watertown, where he once again put himself at odds with the law. That year, he became involved with Cardin Drabston, one of his father’s servants, and she became pregnant. A grand jury in Watertown indicted Grant for fornication in 1678, but the charges did not stop there. “Drabston,” the account goes on to say, “brought forth a child into the world on the 30th of June last, which was murdered & kept five dayes & then buried.” Though the magistrates did not implicate Grant in the infanticide, they did charge him with concealing it. He pled not guilty, and officials soon acquitted him of the most serious charges — though it remains likely he suffered another public whipping. Grant died in 1692, just short of his fiftieth birthday.

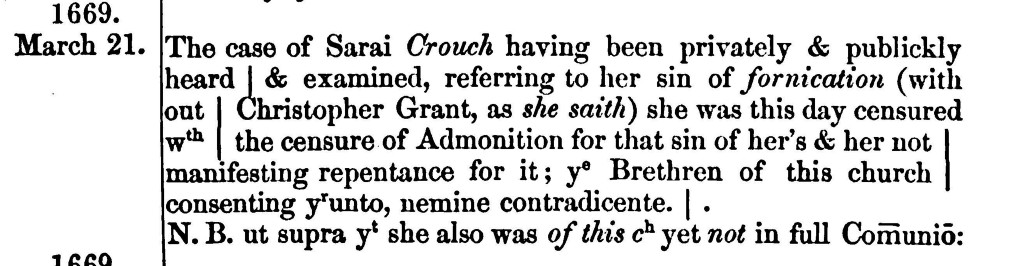

As for Crouch, the years immediately following her indictment were equally fraught with drama. A year removed from the birth of her first child, she again faced charges of fornication after a second pregnancy came to light. In the Charlestown Church Records, a listing exists, dated March 13, 1670. It reads: “This church, having heard the case of Sarai Crouch, referring to her sin of fornication With Thomas Jones, voted that she should be excomunicated for [persisting] so impenitently, incorrigibly in sin, while under censure for that committed March 21. 1669.” This time, Crouch did not refute that Jones was the father. Though the Church planned to excommunicate her, it decided to defer final judgment until after the delivery of her child. Ultimately, it left the door open for her return to the congregation, assuming she properly repented. This likely had something to do with a subsequent file, which can also still be found in the records of the Middlesex County Court.

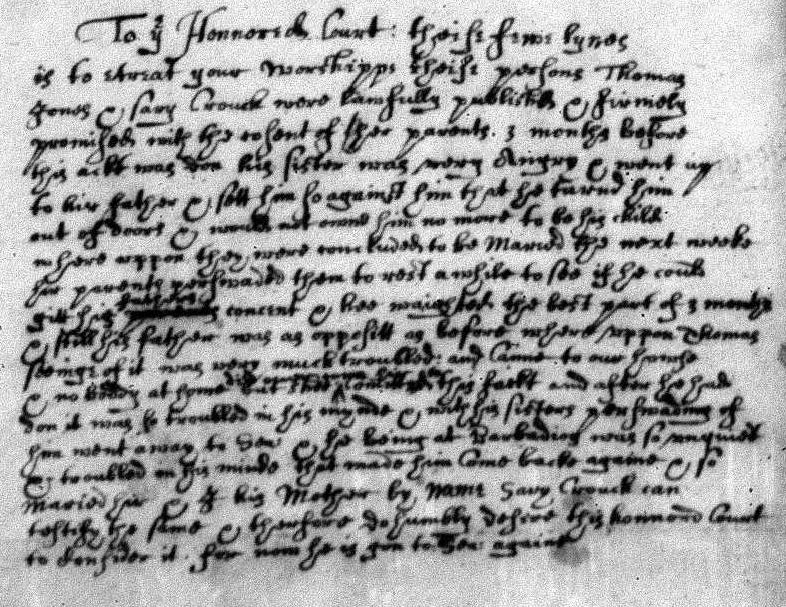

In an undated petition, likely written before Crouch’s April 1670 court date, her parents argued that her second fornication offense occurred amid extenuating circumstances. She and Jones “were lawfully published and firmly promised with the consent of [her] parents 3 months before this act was done.” The match had apparently upset Jones’s sister. She was “very angry and went up to [their] father and set him so against [Thomas] that he turned him out of doors and would not grant him no more to be his child.” The Crouch family, hoping to obtain a proper blessing, had advised the lovers to wait for approval before committing to marriage. Three months later, Jones’s father remained unrelenting. “Thomas hearing of it was much troubled and came to our house,” wrote Crouch’s parents, but nobody “was there but Sarah.” During this time, Jones “did overcome her to commit this act and after he had done it he was so troubled in his mind, and with his sister persuading him, he went away to sea.” After months working in Barbados, Jones was “so anguished” he decided to come back and marry Crouch with or without his parents’ blessing. The pair married and had five children over the next nine years.

After Jones died in 1679, Crouch married a man named Thomas Stanford. Together, they had at least nine additional children, securing her position as an early colonial ancestor for thousands of future Americans. More than a happy ending to a life otherwise defined by trauma, Sarah Crouch’s productive marriages offer an alternative view on the nature of our national origins. Americans with deep roots in Massachusetts descend not only from the morally righteous denizens of John Winthrop’s famed “city upon a hill,” but also from flawed and ordinary people — many of whom were unrepentantly themselves and often paid the price for it.

Daniel Crown writes about history and books.

A Note on Sources

The material in this article is drawn and quoted directly from original depositions found in Folio 52 of the Middlesex County Court Records (except where noted). I obtained these documents on microfilm through FamilySearch.org. I’d like to thank Elizabeth Bouvier, Head of Archives at the Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court, for helping me isolate the files I needed. I first encountered the story of Crouch v. Grant through a brief mention in the essay “Puritans and Sex” by Edmund Morgan and later again in Roger Thompson’s Sex in Middlesex: Popular Mores in Massachusetts County, 1649–1699. Though these works served as roadmaps to key sources, I referred only to my own transcriptions of the original colonial-era chicken scratch when piecing together my narrative. In the process, I found unpublished testimony — most notably from Sarah Largin and Samuel Church — which provides new insight into how Sarah Crouch spent the months leading up to her trial, as well as the circumstances surrounding her marriage to Thomas Jones. Other primary sources included The Records of the Court of Assistants of Massachusetts Bay, The Record-Book of the First Church in Charlestown, and The General Laws and Liberties of the Massachusetts Colony: Revised & Reprinted.

Jared Kushner's First Hundred Days

Because JARED and IVANKA straddle the millennial and Generation X divide, they love to host parties whenever seasons of their favorite television shows end. IVANKA thought it would be cute to host a season finale party to commemorate her father’s first hundred days in office. She and JARED invited all of their New York friends, though quickly dwindling in number, to their D.C. home.

The doorbell rings. It’s seat fillers IVANKA has paid so the party appears crowded. One of the seat fillers is wearing a t-shirt that reads “I hate Mondays” and another is wearing one, in Stanford colors, that reads “Smartass University.”

IVANKA: Go over there. [Ivanka gestures to her fainting couch, enlivened with gold balloons with the words ‘100 days’ printed on them.] You can eat, but ensure your faces are clean before the guests arrive. [She hands the two seat fillers baby wipes, and then presses her temples so hard that she grimaces slightly.]

[JARED enters. He notices the marks in the flooring, the marks that STEVE BANNON made when he tried dragging the fainting couch to the Potomac River. He calls over one of the waiters, points to a rug on the other side of the room, and demonstrates pulling it over to this side of the room. The waiter shakes his head, points to IVANKA and then mock cuts his throat.]

IVANKA [happily]: I don’t want them making changes unless I’ve signed off on them. The marks on the floor will remind me to micromanage you, and they will remind you that you have failed.

JARED [unhappily]: What time do we get to go back to New York?

IVANKA [putting on surgical gloves]: Go to New York whenever you feel. You know the arrangement.

JARED [trying his damnedest to remember the arrangement, but every time he is able to conjure a bit of it, the memory dissolves]: I thought this was over, like when Don comes up with the Coke ad while he is losing his mind in California. And then he goes back home to New York. I thought this was that?

IVANKA [adjusting the shoulders of one of the seat fillers]: That’s a series finale. This is the season finale. We are killing off —

JARED [perfunctorily]: Bannon?

IVANKA [matter of factly]: No. We have to keep him on staff until right before the 2020 election. Firing him will persuade college educated white people that we are pivoting. And so they will return home to us.

[STEVE BANNON is upstairs, sleeping. He is snoring so loudly that the seat fillers have asked each other whether a wild animal, a bear, maybe a monster, is constrained somewhere. They discuss escape routes, if it comes to that.]

IVANKA [powerfully]: We are killing off taxes.

[The door bell rings again. This time it’s JARED’s brother JOSH, a venture capitalist, and his girlfriend KARLIE KLOSS, a famous model. They’re wearing cool clothes and sunglasses even though it’s raining. They’re talking about how they are Democrats and how anyone who voted for IVANKA’s dad is literally the devil. Like a devil person who stands for the National anthem and who believes that granola is a health food.]

IVANKA [to JOSH and KARLIE]: Hello girls. [IVANKA goes in to air kiss JOSH but instead walks past him.]

KARLIE: Just FYI I’m only here because Josh said you built a really nice yoga studio in your subterranean addition. I doubted him because how could there be natural light in a basement, but here we are. [KARLIE takes a selfie, adjusts the filter and tags #antifa.] It’s really dangerous how your administration produces everything like it’s a television show.

[KARLIE goes downstairs to salute the sun bathed in artificial light. JARED tries impressing his brother by showing him their sophisticated projector, which is airing the NBA playoffs on the large blank wall.]

IVANKA [from her fainting couch]: Your brother doesn’t care about that. Pitch him.

JARED [obediently]: It’s Craigslist but for —

JOSH [genuinely but while entering his last meal on MyFitnessPal app]: How are you?

JARED [disarmed because someone asked him how he is]: No one is going to come to this party.

JOSH [in troubleshooting mode]: Who else did you invite?

JARED [counting on his fingers]: Mindy Kaling, Tom Hanks, Senator Gillibrand, the girl who sings Rehab.

JOSH: Jared, those are all Democrats. And Amy Winehouse has been dead for like five years. [JOSH points to the NBA playoffs.] You should be showing a NASCAR race or something. You’re a Republican now. You should’ve invited like Karlie’s friend Taylor or Eli Manning maybe. Who do we know who hunts?

JARED [whispering but exaggerating]: My life is a nightmare.

JOSH: Download MyFitnessPal.

JARED: We don’t have to lose weight though.

JOSH [mentoring]: Big bro, you have to get better at hacking reality. If I’ve learned anything working in venture capital, it’s that. [JOSH takes JARED’s phone.] Is your password still fuckchuck?

[JOSH types ‘fuckchuck’ into JARED’s app store, and tosses the phone back. JARED wants to hack reality — he really does — but he has never been an athlete and so he drops his phone, cracking its screen. IVANKA sighs audibly from the other side of the room, yells that her husband can’t catch, and procures a fresh phone from her enormous bag.]

JOSH [powering on JARED’s new phone, and then doing everything all over again]: Trust me. I’ve dated a lot of girls with eating disorders and it’s never about losing weight. It’s about control. Now you can watch my meals. Watch me be in control and that’ll remind you to be in control.

JARED [gesturing to Steph Curry, projected onto his wall]: Why do you think he does that with his mouth guard all the time?

JOSH: You’re looking at it all wrong. Who gives a fuck about the mouth guard? He’s a tiny basketball player. He hacked his own system. Like you are going to. More like Steph. Less like Jared. Say it back to me.

[IVANKA is still reclining on her fainting couch. She is bouncing ideas off the waiter, assessing how he reacts when she says that next season’s arcs include rumors that Justice Kennedy is retiring, and a trade war with Canada over kayaks and Tim Hortons.]

JARED: It’s just I thought we got to move home after today.

JOSH [wisely]: What’s home even? Like where we grew up? [JOSH holds up his phone to JARED’s face.] This is where we live, big bro. We are globalists. We carry our homes with us everywhere we go. In our pockets.

JARED [while texting his mother that JOSH arrived safely]: Thanks for coming down, brother. I really appreciate it.

JOSH [reasonably]: I’m here because we are both rich. Plutocrats stick together. Never forget that, brother. Now, where in the hell is Gary Cohn? I’m raising another round.

[Convinced that every single person has something to teach him, a lesson he gleaned from a business book he bought at the Acela news stand this morning, JOSH approaches the seat fillers to make small talk with them.]

JOSH [to JARED]: Where did you find these girls?

JARED: It’s what I was telling you before. Craigslist, but exclusively for human trafficking.

IVANKA [from her fainting couch]: Jared, please unspeak that, and then reframe.

JOSH [excitedly, like he orchestrated a discounted share sale in an early round of financing]: Tatiana got into all eight Ivies.

TATIANA, SEAT FILLER #1: And Stanford.

JOSH: And this awful t-shirt is made from the detritus that commercial fishing operations accumulate in their nets.

TATIANA, SEAT FILLER #1 [actually pitching]: We are nearly dolphin safe.

JOSH [lying]: Venture capital has taught me to wring out bias from all my decisions. That’s why I struck up a conversation with your seat filler. And hired her. [JOSH mentors TATIANA, SEAT FILLER #1.] You’ll start Harvard next year. Malia is doing that too.

KARLIE [reemerging from her practice, and feeling refreshed and calm until she hears STEVE BANNON snoring one floor up]: What the fuck is going on up there? It sounds like a wounded animal fighting a second, more wounded animal. Let’s go, Josh.

JOSH: Karlie’s right. I need to call Malia’s dad about speaking at my fund. [JOSH and KARLIE make out and then leave.] Remember, Jared. More like Steph, less like you.

[JARED texts Justice Neil Gorsuch and some Congressional Republicans and asks them if they’d like to commemorate the first one hundred days of Trump by watching a stock car race. IVANKA texts her dad that trade war with Canada is market testing well.]

L train, Below the East River

Illustration: Forsyth Harmon

A large and shallow, buttercup-yellow box, wider than a pizza box, bearing, in neat black letters along one side, the words “KERRI MEMORIES.” This was your lap’s cargo, as you rode the eastbound L train to Brooklyn on a Monday evening. Where were you taking them? To Kerri? Would she want them? It was egregious, this big bright box. It would have been better if the box were gray or black. Then I might not even have noticed you, with your sad eyes and plump moustache and belly — a man of divorceable age.

The sunshine color seemed so cruel, a kind of travesty of sadness, and I thought this even before I noted, with a misplaced guilt, that it was the same color as my wedding dress. While there, resting vast in your arms, were what I thought must be manifestations of your maybe-ex-wife. Letters from Kerri, photographs of Kerri, ticket stubs and trinkets. All the pocket-softened vestiges of you and Kerri, Kerri and you. I will never know who Kerri is, and you will never not-know.

I looked away. A quick, ridiculous vision: everyone in New York going about the city carrying an unwieldy box in a pretty color, labelled with the name of their foremost pain. Decreed by bland, bluff de Blasio — himself a box-faced sort of guy. One box per person, to be carried at all times. Shades of lavender and rose and mint green, like macarons or lingerie. Women setting them neatly in their laps to eat a glum sandwich on a park bench. Men slung against a subway pole, hoiking them up under their arms with a mild glance down at the label, as if they didn’t know what it said, as if it weren’t the one thing they couldn’t forget.

I was sitting next to you, compacted, and it didn’t feel right that someone should be thinking all this of you, or that you and your Kerri memories should be right there visible at my left knee. My companion, standing at the rail in front of me, swaying a bit as we hurtled beneath the East River, texted me a zoomed-in photograph of your label. I texted back “:(“ , then I looked up and we each made a small sadface, a real one, to each other.

A moment later, it was show time — a river crossing’s worth of circus — and you whipped out your phone and began filming, leaning forward over KERRI MEMORIES so as to get a better shot of the guys spinning their bodies with all that extraordinary every-day athleticism. I watched them in miniature on your screen and wondered what you were going to do with this video. Where does any of it go— the big yellow boxes and the digital files.

When the dancers finished you didn’t stop filming. Instead you wheeled your phone steadily, fingers and thumbs in a taut frame around its corners, to the smiles and relenting applause of the people opposite. You looked dogged as you filmed them, as though this were a military maneuver, as though, in some way, you felt it to be a thing on which your life depended.

The Punch

Notes on life

Liana Finck’s cartoons appear in The New Yorker and on Catapult. She posts her drawings on Instagram.

A Hundred Days Later

A reflection in verse

Give or take a day or two a hundred days have passed

And every single second’s somehow sadder than the last

You try to laugh, you try to joke, you try to disappear

But nothing takes you out of it: The horror’s always here

The world won’t let you look away, there’s nowhere you can hide

The anger’s out there on the street, the terror’s there inside

It isn’t just an awful dream, this thing you can’t ignore

Even poems don’t help, so I won’t do this anymore

Previously: