The Five Worst Kinds of Co-Workers

So, according to New York magazine, a local woman has quit her job and, with her husband earning a “low-six-figure income,” she has decided to raise children and not work at all! What an amazing specimen. But this isn’t your grandparents’ housewifery. “This is not the retreat from high-pressure workplaces of a previous generation but rather a more active awakening to the virtues of the way things used to be,” claims New York magazine, discussing how said lady rubs her husband’s feet when he comes home. (“Active awakening”! I’m really stuck on that language. I think it says that on a package of live yeast in my refrigerator? Also: there should be some mention of how the workplace has actually retreated from us, in the form of the radical instability of employment now, but perhaps I’ll leave my Marxist claptrap aside here.) In any event, I’m not sure I can question her choices. “HAVING IT ALL,” I have learned in the course of having had it all myself for some time now, often means doing a really bad job at everything.

But really? I’m glad more parents are staying at home instead of working. Every single person (by “single” I mean unmarried!) knows that on average — not in the specific, not in every case, but in the aggregate! — that they may be tasked with pulling the weight for certain kinds of employees. It goes like this pretty much:

• Smokers.

• Parents (particularly of two or more children).

• The Jews.

• Marrieds.

• People who work at home.

Smokers in Sweden, scientists have explained, took 11 more sick days on average than non-smokers. These poor people also take off for “smoke breaks” regularly. In the mind of a smoker, they all live in France, and work is something you do between luxurious smoky breaks.

Then parents! They are terrible. There is always some crisis with little Donkey and Munificent’s ears, or week-long applications for private school. Parents are terrible coworkers, you never know where they are. Sometimes they are hiding in a lactation closet and refusing to do their work, or they are “on their way to the office,” or they are busy reading New York magazine to learn what might be wrong with their children.

And then the Jews! They put down their BlackBerries on Friday nights and won’t answer you until Sunday. I appreciate a structured calendar, and I definitely appreciate time for reflection and solitude, don’t get me wrong, but even after working weekends alone without our Jews, then each year when the gentiles come back to work after Labor Day, we run pell-mell into Rosh Hashanah, Yom Kippur and Sukkot. Our biggest lesbian atheist Reform Jews try to run this holiday routine, even when you’re like “girl, please, you don’t even know Sukkot from Simchat.” By then it’s practically November, and we’ve just gone on without them.

Married people are always disappearing for spouse-related reasons and then leaving early to do gross things with each other while being cruel to single people. And everyone knows that people who work at home don’t do anything all day basically.

And while we’re on this topic? To be honest, the gays aren’t much better, by the way, with their late nights and drug hangovers, but let’s not get into that, wouldn’t want to offend anyone. Anyway! God forbid you telecommute with a smoking gay Jew with children, just quit your job and become a stay-at-home mom and get ready to do some serious foot-rubbing.

Do You Know Why We Tell Ourselves Stories?

“’We tell ourselves stories in order to live,’ Joan Didion wrote in ‘The White Album.’”

— Man, did she ever! Look, Joan Didion is great and all. I’m glad her genius has been acknowledged in her lifetime, so that she is aware of just how appreciated she is. And it’s terrific that her ability to transform our seemingly ineffable motivations into pithy expressions of undeniable truth is so universally venerated that scarcely a week goes by without a citation of this insight. But maybe we could give it a little bit of a rest before we devalue it completely? That would be swell. (Same deal with Philip Larkin, in re: your parents.) Also, while I have you here: Everyone is always selling somebody out. It’s only writers who think that they do it in a unique or noteworthy way. Alright, carry on.

Shocking Rich People Purge at Rich People Social Media Network!

A weekend of the long social media knives apparently just took place at rich people social network A Small World. The email excerpted above was sent to members this morning. The private social network, sold to Harvey Weinstein and then dumped by him, stopped taking new members back in February. Now they’ve purged their rolls of what were apparently troublemakers and/or poor people.

Meanwhile, over on A Small World founder Erik Wachmeister’s new site, “Best of All Worlds,” the interface is busy asking me what I am an expert in. Choices so far include “Art,” “Philanthropy,” “Farming” and “Hunting.”

Do you know more about the A Small World shenanigans? Let us know! (By having your staff deliver a handwritten note in a deliciously creamy envelope.)

Whistleblower: Met Fundraising Tactics Go Beyond Stink-Eye

“A former Metropolitan Museum of Art supervisor claims he was often ordered to threaten the removal of visitors who refused to fork over the recommended high admission fees. ‘I arranged for security officers to forcibly remove the museum visitors who demanded entry without paying,’ the whistleblower told The Post.”

— Have you been tossed out of the Met for not paying $25? Tell us in the comments!

Newspapers Maybe Not Much of a Growth Industry

“Employment of full-time professional editorial staff peaked at 56,900 in 1989. By the end of 2011, the last year for which data are available, employment had fallen by 24%, according to the American Society of News Editors. When figures for 2012 are compiled, newsroom workforce will likely be below 40,000.”

— Of the many bits in this survey of the current American news business — the cable news audience is stalled forever at 1.9 million people! TIME’s newsstand sales dropped 27% in a year! — the 24% drop in newspaper editorial employees is the most instructive for those of you young people thinking about a major. (Journalism is always a terrible major.)

Photo by auremar, via Shutterstock

Dog Faces: What Are They Saying?

Recently there has been some discussion about whether the world is a better place to live in now or if the whole thing is hurtling toward the cosmic dustbin with a cinderblock on the accelerator as it tosses empties out the window while blasting deadmau5 from the speakers. On the one hand, you have people like cognitive scientist Steven Pinker arguing that we are currently experiencing “the most peaceable era in the existence of our species.” On the other hand, a quick stroll through the papers is all you need to remind you that, no, you’re not wrong, the world is completely crazy and getting worse every second. Let’s put aside the sub-debate over whether or not the world has always been this astoundingly insane and we’re just more aware of it now because technology allows every sad secluded outcast to toss their most banal thoughts into the limitless litany of suffering, horror and loneliness that is the permanent record of our sorrowful existence. Can the weight of all that agony — a heaping helping of terror, dread and boredom — do anything but put further pressure on our already shattered pysches? How much longer can we pretend that it’s going to be okay when we all know that the inevitable end is wending its way towards us with frightening speed and a lust for blood that will not be easily sated? On the other hand, apparently we can tell what dogs are feeling just by looking at their faces

, so maybe it’s not all bad.

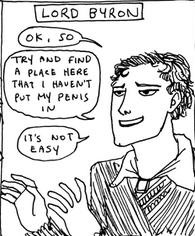

How To Be A Monster: Life Lessons From Lord Byron

How To Be A Monster: Life Lessons From Lord Byron

In 1816, a young doctor named John Polidori was offered the position as traveling physician to George Gordon, Lord Byron. Polidori was saturnine, caustic, ambitious, well-educated and handsome. He had graduated from medical school at 19 (as unusual then as now) and this offer came not a year later. Over the objections of his family, he accepted. Polidori had literary ambitions; here was an amazingly famous poet asking him to join him on a tour of the Continent. It must have felt like fate was tugging him along. In confirmation of how well things were going, a publisher offered him 500 pounds to keep a diary of his travels with the poet (500 pounds… in 1816).

It was spring. Byron was leaving England forever, a cloud of infamy hanging over him. (He is one of the few people you can write something like that about and have it be true; that is part of why he’s so satisfying.) He had a carriage made, modeled after Napoleon’s, this a measure of his own sense of emperor-like preeminence in the world. Byron was, even by the standards of the time, a chronic overpacker: china, books, clothing, bedding, pistols, a dog, the dog’s special mat, more books, a servant or two, and Polidori, buzzing like some excited insect, were all packed away. (One account has a peacock and a monkey making the trip too.) The carriage was so overloaded it kept breaking down. The doctor kept breaking down too, with spells of dizziness and fainting, and the patient had to look after him. They progressed this way through Belgium and then up the Rhine. When they reached their hotel in Geneva, Byron listed his age in the hotel registry as “100.”

If you have any interest in Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein or vampires or Romantic poets or, who knows, Swiss tourism, you’ve most likely read Polidori’s name. He’s a curio, Polly Dolly, most notable not for what he wrote but for being nearby when other people wrote things. It’s a strange afterlife; to think you’ve landed a leading role, and then there you are, on stage, sure, and with big names too, but fixed to a mark far upstage and over to the left, near the wings, in the half-dark where the spotlight doesn’t quite reach. “Poor Polidori.” That’s how Mary Shelley referred to him, writing years later. And he was. Here is how he creeps into letters, like this one written by Byron: “Dr. Polidori is not here, but at Diodati, left behind in hospital with a sprained ankle, which he acquired in tumbling from a wall — he can’t jump.” It was John Polidori’s misfortune to be comic without having a sense of humor, to wish to be a great writer but to be a terrible one, to be unusually bright but surrounded for one summer by people who were titanically brighter, and to have just enough of an awareness of all of this to make him perpetually uneasy. Also, he couldn’t jump. Poor Polidori.

One short story he wrote, though, remains important, a vampire story that was read across Europe when it came out and led the way to Dracula. But even that story was not all Polidori’s own. In a nice bit of literary vampiricism, he fed off a sketch by Byron to write it and the story was first published under Byron’s name (hence all the attention it got), so he’s instructive, too, as a reminder of all that writers and vampires have in common.

***

An aristocratic vampire bored by his immortality — we’re accustomed to that creature now. But this sort of vampire is relatively new. As Paul Barber describes in his wonderful book, Vampires, Burial, and Death, the vampires that populated European folklore for centuries were Slavic peasant and villager revenants, ordinary people rising from their graves bloated and ruddy, with long fingernails and grave dirt in their hair. Polidori based his story “The Vampyre” on a “Fragment” written a few years before by Byron. In each story, the vampire is rich, lordly, weighted down by dissatisfaction.

He is, in other words, a personage not so unlike Lord Byron. In Polidori’s story, the vampire, Lord Ruthven, has cold grey eyes. He is bored. It’s impossible to know what he’s thinking. He mixes in the highest society. He is well thought of, but, secretly, a predator eager to lead virtue astray. He and a young idealistic companion, Aubrey, set off on a tour by carriage of Europe. There is no mention of whether a monkey and a peacock are with them, but the rest of it sounds familiar.

“The Vampyre” was first published, in 1819, in New Monthly Magazine as a story by Byron. It created an international stir. A play and then an opera were based on it, events that seem unlikely to have occurred if the story had gone into the world as the work of a London physician. It’s widely assumed that Polidori passed the story off as Byron’s in an intentional imposture, but the evidence there is murky. Just as possible is that, the manuscript having passed through several hands after Polidori wrote it, the details of its connection to Byron grew confused on the way to publication. (Byron, breezily waving it off: “… I scarcely think anyone who knows me would believe the thing in the Magazine to be mine, even if they saw it in my own hieroglyphics.” He might just as well have added: “He can’t jump either.”)

Whatever his intentions there, the point remains that two years after he’d left Byron’s employment Polidori was writing a needling story based on Byron and using the vampiric character Byron himself had created to skewer him. It was like biting him with his own teeth. To add an extra silvery jab, he’d borrowed the name Ruthven, too. It came from Lord Ruthven Glenarvon, the villain of a wondrously batshit Gothic novel by Lady Caroline Lamb, a former lover of Byron’s. Her book was simultaneously a work of revenge and a provocation to renew an affair that had ended four years before: I hate you, let’s do that again. (It worked as neither. Instead of a ‘kiss and tell,’ Byron called it a ‘fuck and publish.’ After reading it, he neither returned to her nor was wounded in his retreat.) It came out in May 1816, as he and Polidori were first scraping into Geneva.

***

It was Caroline Lamb who called Byron “mad, bad and dangerous to know.” The level of celebrity he enjoyed when they started their affair was boggling. His future wife Annabella Milbanke termed it “Byromania,” observing that “the Byronic ‘look’ was mimicked everywhere by people who ‘practised at the glass, in the hope of catching the curl of the upper lip, and the scowl of the brow.’”

But Byron left England a monster, “a second Caligula.” Among his rumored crimes: He’d had a long relationship with his half-sister (leading to one child), carried on affairs with numerous actresses and married society women, and “corrupted” many young men. The rumors were all quite factual. He’d been engaging in such bad behavior for some time, but now the details were in wide circulation, Byron having committed the fatal error of marrying Milbanke, treating her abominably for the duration of their short marriage, then banishing her from the house a month after she’d had his child. Outraged, stonily disillusioned — if this were a movie she’d be played in these scenes by a thin column of dark smoke — Lady Byron hired a barrister and a gang of other counsel, including an attorney named Stephen Lushington, who, despite the delightful relaxed slurring suggested by his name, proved a prudent, sober and, alas for Byron, rather inexorable advisor. Lushington was shocked by all the secrets Lady Byron had to tell him. As Byron sailed, bailiffs were seizing what property remained at his Piccadilly Terrace home, including “his birds & squirrel.”

***

Lake Geneva: Blues and deeper blues. It was along the shore here that, one morning, the poet Percy Bysshe Shelley, his companion and soon-to-be-wife Mary (her last name Godwin still, not yet Shelley), and Mary’s stepsister Claire Clairmont were out walking. In love, electric, comet-like, Claire had seduced Byron with commendable dispatch before he sailed, then hurtled herself from England, hooking Mary and Shelley along with her, to await his arrival in Switzerland. Claire had left notes and letters of greeting for him at their hotel. Byron had ignored them. Now she was standing on the beach as he and Polidori returned from a morning excursion on the lake. As he clumped to shore, leaving Polidori floating in the boat, he didn’t yet know she was pregnant.

In a letter to his half-sister Augusta, Byron later wrote: “What could I do? — a foolish girl — in spite of all I could say or do — would come after me — or rather went before me — for I found her here. … I could not exactly play the Stoic with a woman — who had scrambled eight hundred miles to unphilosophize me.”

Here is Claire to him: “I know not how to address you. I cannot call you friend for though I love you you do not feel even interest for me; fate has ordained that the slightest accident that should befall you should be agony to me; but were I to float by your window drowned all you would say would be ‘Ah voila.’”

And here is Polidori, writing in his diary the same evening as the beach meeting, with characteristic blunt appraisal: “Dined, P[ercy] S[helley], the author of Queen Maab, came; bashful, shy, consumptive; twenty-six; separated from his wife; keeps the two daughters of Godwin who practice his theories; one L[ord] B[yron]’s.”

Shelley was actually 24, not 26, to Polidori’s 21. Mary was 16; although already she’d lost a child born prematurely and her second child with Shelley, William, had been born that January. Claire was newly 18. Lord Byron, the old man of the group, was 28. You can forget that about them — how astonishingly young they all were that summer. Not too long before Claire had been “Jane Clairmont,” then she became “Clair” before finally settling on “Claire” as alluring and sophisticated enough — that’s how young she was. Shelley had fled England with money problems, while Mary’s elopement with him and Claire’s involvement in it had cut off both girls from their home. Of the five people grouped together that day, only Polly Dolly had a family who would have welcomed him home unreservedly. In this light it doesn’t seem so surprising that they would soon all be writing about monsters (and in Mary and Byron’s case, quite sympathetically, too). Meanwhile, in the hotel and around the city, rumors circulated about who might be sleeping with whom (thrilling conjecture: everyone with everyone else). Byron’s notoriety travelled with him. When he attended a society party in Geneva, a woman fainted when he entered the room. (Byron would later downplay the drama of this episode by pointing out that the woman who had fainted was a novelist and that no sooner had she fainted than someone exclaimed, “This is too much — at sixty-five years of age!”)

To save money and regain some privacy, Byron moved from the hotel to the Villa Diodati, in Cologny, a few miles (or sail across the lake) from Geneva. Shelley rented another, smaller home nearby. It was a short walk between the houses, along a path that traversed terraced green vineyards. Hum of insects, cry of birds, smell of summer heavy in the air. Byron and Polidori were standing outside the villa one day when Mary Shelley approached up the path. Knowing the doctor had a crush on her; Byron urged him to jump down from where they stood and offer her his arm. He did, landed awkwardly and that’s how he sprained his ankle. Poor Polidori.

The fine days gave way to rain, which turned “incessant.” After a golden month spent boating and idling in the sun, the group was confined indoors. They read ghost stories aloud. Then, as Mary Shelley recounted it:

‘We will each write a ghost story,’ said Lord Byron, and his proposition was acceded to. There were four of us. The noble author began a tale, a fragment of which he printed at the end of his poem of Mazeppa. Shelley… commenced one founded on the experiences of his early life. Poor Polidori had some terrible idea about a skull-headed lady who was so punished for peeping through a keyhole — what to see I forget — something very shocking and wrong of course….

For herself, Mary says she thought and thought, and then, many nights later, in a state between waking and a dream, had the vision that led to her masterpiece Frankenstein, the story of a scientist whose fate is yoked to the wretched, stitched-up monster to whom he gave life. Byron’s ghost story remained a fragment, but he also wrote the poem “Darkness” that summer as well as the third canto of Childe Harold. (Infuriatingly if you were his companion, he started work on the latter while on the boat from Dover, while everyone else was being horrifically seasick.)

And there was Polidori with only his skull-headed lady to show (at least in Mary Shelley’s account). It’s easy to make fun of Polidori; he was capable, like so many terrible writers, of a sort of dreadful productivity and eagerness to read his works aloud: “later they suffered a reading of an atrocious play by Polly Dolly” goes a typical biographical scene. (After a few months of that you, too, might have been urging him to jump down from great heights.) His formal productions sound turgid, complicated… young; it’s too bad as that excessiveness would have worked against the bluntness that is so marked and funny when you read his travel diary. After meeting Stendhal: “a fat lascivious man. … He related many anecdotes — I don’t remember them.” About Belgium: “the country is tiresomely beautiful.” About Byron himself: “As soon as he reached his room, Lord Byron fell like a thunderbolt upon the chambermaid.”

***

Byron later described Polidori as “exactly the kind of person to whom, if he fell overboard, one would hold out a straw, to know if the adage be true that drowning men catch at straws.” Irritated and provoked, his manner toward him would metronome-tick back and forth between cruelty and apology. When Polidori sprained his ankle, it was Byron who carried him to the house, settling him on a sofa with pillows (a completely un-Byronic bit of solicitude). It wasn’t the only such stricken gesture. At no small expense, he hired a coach to take the young doctor around to Geneva society parties; another time he bought him an expensive watch. Over the summer, as Polidori got further out of hand, drinking too much and roaming around the villa, it was Byron who vacated the house. Who is the vampire in such a dynamic — who the victim, who the parasite? It switches back and forth, back and forth. Not hours after Byron was meekly plumping pillows for him, Polidori was again reading one of his plays aloud to the group. “All agreed it was worth nothing,” he recorded.

Out on the water, one afternoon, Polidori accidentally struck Byron in the knee with his oar. As Mary Shelley later relayed it, Byron “without speaking, turned his face away to hide the pain. After a moment he said, ‘Be so kind, Polidori, another time, to take more care, for you hurt me very much.’ — ‘I am glad of it,’ answered the other; ‘I am glad to see you can suffer pain.’”

On a side trip with Shelley, as the poets stood in “the middle of a beautiful wood,” Byron breathed out, “Thank God Polidori is not here.”

***

“Learn from me, if not by my precepts, at least by my example, how dangerous is the acquirement of knowledge and how much happier that man is who believes his native town to be the world, than he who aspires to become greater than his nature will allow.” — Frankenstein

Polidori and Byron parted ways in September 1816, after five stormy months in each other’s company. Polidori traveled on into Italy. He drifted. He took on a few more patients, returned to England, switched from medicine to studying law, and then, in 1821, died. He was 26. According to his family, he committed suicide by swallowing prussic acid after the pressure of some gambling debts he couldn’t pay grew too much. (At the inquest a family servant said in a statement that Polidori had recently suffered a head injury after “being thrown out of his gig.” This, too, may have contributed.)

Polidori’s father was Italian, a former secretary to the dramatist and poet Alfieri; his mother was English. Polidori had grown up among the expats of Soho; one great lure of the trip with Byron was the chance to see Italy. His sister Frances married Gabriele Rossetti, and was the mother of the poet Christina Rosetti and the poet/painter Dante Gabriel Rossetti. Their brother William Rossetti, also a writer, became the editor of Polidori’s diaries, although, like his siblings, he never knew his uncle. His work on the journals is oddly touching in its deftness and humor, like the penciling of an older, wiser Polidori surrogate. Of the position with Byron, William writes in the introduction: “The day when the young doctor obtained the post of travelling physician to the famous poet… must, no doubt, have been regarded by him and by some of his family as a supremely auspicious one, although in fact it turned out the reverse…. Polidori’s father had foreseen, in the Byronic scheme, disappointment as only too likely, and he opposed the project, but without success.”

***

Lord Byron died three years after Polidori, from a fever after having traveled to Greece to help fight for Greek independence. Long after news of Byron’s death reached England, people still reported seeing him on the street.

His “Fragment” is a slight thing, and yet the description of himself (for it is clearly a self-portrait) as the vampire is telling: “It was evident that he was a prey to some cureless disquiet; but whether it arose from ambition, love, remorse, grief, from one or all of these, or merely from a morbid temperament akin to disease, I could not discover.”

The pages, he later confided, had been written on an old account book of his wife’s, which contained “the word ‘Household’ written by her twice on the inside blank page of the Covers.” It was, as one biographer notes, “the only specimen Byron still had of his wife’s writing, other than her signature on the separation deed.”

***

Most of my first impressions of Polidori came from the asides and footnotes that appeared in other people’s biographies. Bits and pieces of a person. Read enough of these mentions (“mentally troubled man,” “embryo author”), stitch them together and a human form begins to take shape: a footnote Frankenstein. Of all the foototes, this one, from Richard Holmes’ The Pursuit, was the one where Polidori’s… essential Polidoriness most asserted itself. It’s attached to a sentence about Percy Shelley’s dislike for the Austrian troops then in Venice and so crops up as a non sequitur:

* Dr. Polidori was arrested in 1817 for asking a trooper to remove his busby at the opera.

Think about it, add it to your picture of John Polidori you’ve sewn together. Of course he was arrested in 1817 for asking a trooper to remove his busby at the opera. There he is, motioning from the wings. Vehement, insistent, even standing in the half-dark. He wants you to see him there.

Related: How To Give Birth To A Rabbit

Carrie Frye is here and here. Byron cartoon from this Hark! A Vagrant strip by Kate Beaton, used with permission; photo of Lake Geneva by Schnägglit; photo of Villa Diodati by Robertgrassi.

New York City, March 14, 2013

★ The early daylight was subdued, and there was a whipping wind on the avenue. Winter was claiming its rights by the calendar. After the shelter of the subway, the cold was eye-watering. The hanging flags for the bar and the restaurant flapped parallel to the sidewalk. The clouds were shredded by afternoon, leaving patches or islands of sunlight to cling to while walking. The wind crawled up the coat sleeves. People were out in their long down coats again, their furs. A woman at the curb wore something ambiguously between a coat and a bathrobe, equally ambiguous between real and fake fur, all in shades of blue.

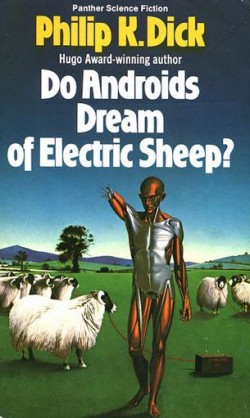

The Titles of Philip K. Dick's Novels, In Order of Sheer Awesomeness

by Ted Pillow

46. Nick and the Glimmung

45. Galactic Pot-Healer

44. The Zap Gun

43. Mary and the Giant

42. A Maze of Death

41. The Game-Players of Titan

40. The Broken Bubble

39. Dr. Bloodmoney, or How We Got Along After the Bomb

38. The Ganymede Takeover

37. Voices from the Street

36. Deus Irae

35. Confessions of a Crap Artist

34. Vulcan’s Hammer

33. The Crack in Space

32. Counter-Clock World

31. Martian Time-Slip

30. Radio Free Albemuth

29. The Simulacra

28. The Penultimate Truth

27. The Transmigration of Timothy Archer

26. Ubik

25. Time Out of Joint

24. Eye in the Sky

23. VALIS

22. The Man in the High Castle

21. The Cosmic Puppets

20. Gather Yourselves Together

19. Lies, Inc. (an expanded, republished version of “The Unteleported Man”)

18. Solar Lottery

17. The World Jones Made

16. Clans of the Alphane Moon

15. Dr. Futurity

14. The Three Stigmata of Palmer Eldritch

13. A Scanner Darkly

12. We Can Build You

11. The Divine Invasion

10. Puttering About in a Small Land

9. The Unteleported Man

8. In Milton Lumky Territory

7. The Man Who Japed

6. Our Friends from Frolix 8

5. Now Wait for Last Year

4. Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep?

3. Humpty Dumpty in Oakland

2. The Man Whose Teeth Were All Exactly Alike

1. Flow My Tears, The Policeman Said

Ted Pillow means no harm. His writing can be found at Fanny Pack Spectacular! He tweets @TedPillow.