Why You Hate The Way Other People See And Hear You

“We grow up getting used to all of our asymmetries as reflected in the mirror — parting our hair to the left, the little mole on our right cheek, that chip in our left incisor. When we see a photo of ourselves, all of these tiny differences don’t match up with what our brain expects to see, so we dislike it. Likewise, we live our lives hearing and perfecting our bone-conducted, but not air-conducted, voices.”

Big Bang Remix Drops

“A scientist has ‘remixed’ his version of the sound of the big bang in light of detailed new data gathered by a multi-million pound space probe. Information beamed back from the European Space Agency’s £515m Planck space telescope has already seen physicists revise their estimates of the age of the universe. Now one professor has used the Planck data to create an updated, ‘high fidelity’ rendition of the sound of the early development of the universe more than 13 billion years ago.”

It's Like You Can't Even Fake-Abduct Anyone Anymore

“The kidnapping of a Washington Heights couple on Friday — which set off a three-day police manhunt for the alleged abductors — turned out to be nothing but a surprise party prank. The apparent abduction began Friday around 8:30 p.m. when a man and a woman were forced into a van near W. 176th St. and Haven Ave. by two hooded men who had chased them down, witnesses told cops.”

Thoroughly Magical Things To Do Tonight

You gotta love it when NYC delivers. Look at this calendar of events! Come on! Lil Buck performing to a Philip Glass premiere? Maya Angelou? An examination of Sekou Sundiata? Also I’d be remiss in not pointing out that our own Dave Bry is appearing with Rose Surnow at KGB Bar tonight.

Gay Life Is So Pedestrian Now That You Can't Even Film A Porn At A Sex Party

by Richard Morgan

Rawhide, a leather bar on Eighth Avenue that’s as old as I am, closed this weekend. It’s been open since 1979, and its exit seemed like the latest in a parade of gay ghosts. They’re building condos at St. Vincent’s hospital these days. Gay newspapers and magazines have withered and folded until almost all that’s left is a party picture of Michael Musto and a flyer about go-go boys. There aren’t any gay bookstores in Manhattan anymore (for now?). Now that it’s all gone, the city is primed for a nostalgic luxuriation in old-school Castro District gayness, which is why a plan recently proposed to me seemed so appealing. It was basically gay turducken: going to the largest gay dance party of the year, in the company of two porn actors — and their director, whose intention was to film a porn on-site with both the actors and strangers.

It started a few weeks ago, when I texted someone if they’d be free that weekend and he wrote back that he’d be busy “at the blk party.” Here’s how little I knew about the Black Party: I figured he was talking about either a block party, or a party on Bleecker Street, and I had known but forgotten what he was talking about. When I showed the text to a gay friend, he said it probably meant the Black Party. I nodded like that clarified. I had to Google it. When I lived off Bleecker, gays lost at Father Demo Square would always ask me if I knew where “Mister Black” was, and I found out that it was a nearby party I attended once with a friend from my hometown. But if that doesn’t convey how little I knew about the Black Party, it was maybe a few hours before the big event and I was having a drink in TriBeCa when I realized, that, Oh. Probably everyone is expected to wear black. I was wearing gray and white and periwinkle. “Do people wear black to the Black Party? Is that a rule?” I texted. The reply I got was: “it’s 4000 hot guys dancing and fking in leather or less.” So… yes on wearing black? I am certain I was the only person in attendance wearing a black dress shirt, black slacks and black dress shoes.

But, the whole turducken-y plan intrigued me immensely.

There are many things people don’t tell you about being gay, but one of the more frustrating is that if you’re straight and a virgin, people think you’re just a virgin; but if you’re gay and virgin, people think you’re probably confused. How do you know unless you’ve tried it? Gays are always telling other gays, “What’s the thing you’ve never done sexually but always wanted to try?” The recipients of that question always confess and then do that whatever-it-is right then and there. Sometimes a gay man will suggest something distasteful to me and I’ll demur. Then he’ll often come back with “Don’t be so close-minded,” which I would love a waiter to tell me the next time I ask him to, y’know, hold the anchovies or put the dressing on the side or whatever. In gay life, there is an obligation to no-strings-attached experience, to leaping before you look.

So finally we were in a cab from Williamsburg to the Roseland Ballroom, me and Dale Cooper and Colby Keller. (Those links are pretty safe for work?) The only thing I had on me that wasn’t black was my long white-and-blue notepad that read “NEWS” across the front.

Cooper was wearing what appeared to be an ancient Roman chainmail tunic but was actually a sheer Zara T-shirt; he was going as a retiarius, a net-fighter who was “the most feminine of the gladiators,” he said. The three of us had a thoughtful and fun talk about identity and performance as it relates to film; I never attended Wesleyan, but the cab ride felt like a good equivalent.

In the future, all porn stars will be intellectuals.

— Colby Keller (@colbykeller) March 27, 2013

When we got there, there was a line around the block, which I truly briefly thought was for “Jersey Boys,” playing next door. But the crowd made my mistake obvious. A century ago, Roseland was a whites-only self-styled “home of refined dancing.” Now people in chaps were paying as much as $160 at the door for entrance. Still pretty much whites-only, though.

Inside, we met the ringmaster of our own private circus, Victor G. Jeffreys II, a local artist whose recent gallery show featured T-shirts in silk-screened tessellations of an image of himself masturbating. A handful of the shirts were stained with his ejaculate. At Roseland, he was wearing a thin leather harness but toting several bags of film shoot gear and props. He was also shooting photographs of the event for Gawker, which discovered him when he was outed as a “fameball-tastic” Brooklyn character named “Chimneyhead.”

Of all of us — Cooper, Jeffreys, Gawker’s Rich Juzwiak (who was writing his own piece about the night), Keller and I — only Jeffreys had attended the Black Party in previous years. This was his fourth.

Earlier, I had asked Jeffreys what exactly he planned, or would this be more… whimsical? He had set up three encounters, but wanted four. When I asked him what the three were, he texted: “Hung like a horse blow job. The other two are not clear. Fucking.”

The first encounter was almost right after we got there, around 2 a.m., and it went off as planned. Cooper performed fellatio on a friend of Jeffreys’. This friend wore a rubber horse mask. To say things derailed after that would not only be an understatement, it would also be unfair. I’d say more that the shoot came to terms with the night. People weren’t getting on board.

Smearing peanut butter on my friend’s ass. He sat in gum. PRO TIP: creamy, not chunky. #blackparty twitter.com/DaleDoesPorn/s…

— Dale Cooper (@DaleDoesPorn) March 25, 2013

“It’s one thing to convince people to do anything you want,” said Jeffreys later. “It’s another thing to get them to do it in public and also sign a waiver that’s covered in lube because it’s in my shoe.”

The anticlimax built. Keller got tired and then Keller left.

Jeffreys took some photographs of what Cooper described as the “burlesque-esque” performers working the night’s Coney Island theme. “There isn’t much flesh work for people who don’t do porn,” Cooper said later. To catch a porn star transfixed by a burlesque performance artist is weirdly calming, a kind of validation of subtlety. Porn is so often boring. My turn, your turn, me, you, me, boom, boom boom pow, next! It’s the stuff of Michael Bay, not Stanley Kubrick. It casts itself as drama but without mystery or tension. I’ve had breezes upon the back of my neck that were more erotic.

Jeffreys stumbled upon Rafael Alencar (that’s Not Safe For Work), another porn actor, and managed to shoot another fellatio scene with him.

When Cooper left at 4:30 or 5 a.m., Jeffreys was forced to give up and give in to his own experience of the night. The third scene had been scheduled for near 6 a.m.

“I think what Victor really wanted,” said Cooper in the cab ride back to Brooklyn, “was to clone himself, so he could be director and performer.”

It was stunning in its own weird way. Here were the easiest of fish in the easiest of barrels. How could porn fail at a party predicated on public debauchery? If the carnal hormones didn’t grease the wheels enough, wouldn’t the widespread drug use? Surely there were eager twentysomethings open to a Spring Break “Guys Gone Wild” story to tell their friends. Or older men keen to vampire-ravage the youth out of these actors? Isn’t half the appeal of a leather fetish a sense of domination and control, of being told what to do and when and where and how to do it? How was this crumbling so quickly?

But there’s a difference between debauchery and the appearance of debauchery. “It’s not a sex party,” said Vance Garrett, a frequent creative director of the whole production. He was in the DJ booth behind the wooden Tillie, whose eyes shot sheets of lasers onto the dance floor. “It’s a costume party.”

And the costume of the night was pretty standardized. “Take the same white guy to the same gym and give him the same outfit, then clone him a thousands times and, there ya go: Black Party,” said Cooper. Still, some people were taking their leather and chains very seriously. I pictured them in the leather shops on Christopher Street saying to their boyfriend, “Yeah, but feel this one. It’s more fitted, right?” Some people were dressed like a kind of male Catwoman, or like Quentin Tarantino’s idea of a shirtless ninja biker. Some had very serious chains lacing their pecs but others seemed to have gone to Home Depot and thrown any old chain over their shoulder. Most of the men, dressed confidently, nevertheless shuffled awkwardly, like teens in traffic court wearing a suit for the first time. Or the kind of half-assed showmanship with which people wear spring-loaded shamrock headbands on St. Patrick’s Day. For all the asses on display, they were mostly half-assed. There was not even commitment to the costuming: lots of “Hey, girl! Cute harness!”

When we were checking our coats upon entrance, Juzwiak kept some cash in a Ziploc bag. “I feel like I’m at a water park,” he said. That seemed right. In the game of Want Settle Get, I had wanted Dancer From The Dance, but would’ve settled for Shortbus. I got A Night at the Roxbury, the oontz-oontz Ibiza zombies, the obligation of it all.

“It’s huge, but after 40 hours it’s just walking in circles,” said Jeffreys. “I kept wanting something to happen. I like capturing those surprises. I like documenting what’s real and honest.”

The most honest encounter I had was with an older man with a jaunty forty-niner vibe. He was off to the side of one of the bars that sold $8 bottles of Vitaminwater. He had a shoeshine stand. “Isn’t it hard for people to tell they’ve had a good shoeshine in this dark space?” I asked. He laughed. “Oh, you think they come to me so I can shine their shoes?” he asked. “Sure, I shine their shoes. But I don’t just give a shoeshine. I give attention. That’s all anyone here wants. That’s half the reason the bartenders are so popular; they give everyone attention.”

I nodded but it must’ve been one of those lobotomized nods people give during conversations at loud house music dance parties, because he reached into his shoeshine kit and pulled out a small baggie of two earplugs for me. “It’s not so important to hear it,” he said. “It’s more for your eyes.”

But muting one sense made me want to mute them all. I have spared you from any description of the smell.

I ended up not going to Rawhide for its final night because the only reason for going I could think up was that I’d be able to say that I went. Recently, I’ve started walking down Sixth Avenue to get to Christopher Street. You don’t see or hear the construction at St. Vincent’s that way.

Richard Morgan previously wrote for The Awl about not being American. He misses block parties. Photo by Jeff Bonner.

New York City, March 31, 2013

★★★ The morning was tinted with haze and mild enough to be a little startling. Dress shoes clicked along the sidewalk, past flowerbeds of tulips sprouting, tulips budding, and then tulips in bloom, red and pointy-edged ones. A chilly gust tumbled through the churchyard as the children emerged and scattered, avid for eggs. An overlooked prize glimmered in the ground cover, inches or less from being stepped on. The haze was becoming clouds, and then the clouds were becoming thicker. In the afternoon, the toddler watched and pointed at the airplanes passing, deep gray against the medium gray. Droplets streaked the windows as the daylight and the dryness gave out together, into a shiny, wet night.

Massive Interstate Pile-Ups Are America's Worst New Hobby

Americans have already managed 19 epic highway pile-ups this year, and we’ve still got nine months to go. Hundreds of drivers in Texas, Florida, Indiana, Ohio and Michigan caused death and destruction in the first few months of 2013, with fog and snow and smoke from giant fires often blamed for the chain-reaction disasters.

To be safe, experts advise you not live in any of those states, use public transportation whenever possible, try the very un-American technique of not being right on top of the car in front of you, and also maybe don’t drive anywhere if you can’t see at all.

Photo by Todd Vision.

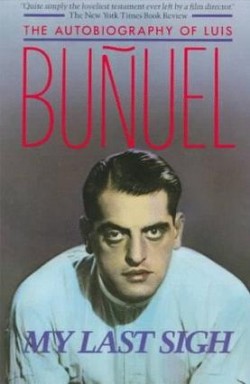

The Autobiography Of Luis Buñuel

by Anthony Paletta

How to sum up a Surrealist’s autobiography? I haven’t the slightest idea. Luis Buñuel’s just-republished My Last Sigh contains, as you might expect, few concrete explanations of anything, but countless provisional manifestoes, an index of cinematic inspirations of bewildering range, more anecdotes than any human has a right to own (he narrowly missed that orgy organized by Charlie Chaplin, but did dismantle a Christmas tree at another party attended by Chaplin — other guests were not amused), and a surprisingly elegiac tone of melancholy. This provides a partial overview, but what else? There’s the family’s pet, an “enormous rat” that accompanied them on trips in a birdcage. This was presumably toted by a servant, as the only thing his father, a “man of rank” would carry in the street was “an elegantly wrapped jar of caviar.” Or, while discussing a budding awareness of sex, the note that a friend “tried to experiment with a mare, but succeeded only in falling off the ladder.” And that’s just before age 10. It is, in any case, a riveting wander in and around Surrealism, cinema and the twentieth century itself.

Any thumbnail sketch of Buñuel’s career looks strangely bifurcated, given the span of nearly fifty years that separates his early work around 1930 (Un Chien Andalou L’Age d’Or) and the late masterworks of the 70s (The Discreet Charm of the Bourgeoisie, The Phantom of Liberty, That Obscure Object of Desire). This of course leaves out countless superb works, but that’s what summaries do. For Buñuel, born in 1900, there was a distinct time before cinema — his peers in age are not Godard or Bergman or Antonioni but Alfred Hitchcock, John Ford, and Jean Renoir. His earliest cinematic experience? A cartoon about “a pig who wore a tricolor sash around his waist and sang.”

As he writes in Last Sigh: “It’s true though, that for the first twenty or thirty years, the cinema was considered more or less the equivalent of the amusement park — good for the common folk, but scarcely an artistic enterprise. No critic thought cinema worth writing about. I remember my mother weeping with despair when, in 1928 or 1929, I announced my intention of making a film. It was as if I’d said: ‘Mother, I want to join the circus and be a clown.’”

***

Buñuel’s village of Calanda, in Aragon, was a sleepy community whose sole product was olive oil. A rigid order of church and family ordered all of life; there, he comments, “the Middle Ages lasted until World War I.” The first automobile appeared in 1919; a purchase of a “liberal” landlord who later scandalized the community when he replaced his blight-stricken vines with American imports. Drums would beat without pause from noon on Good Friday to noon on Holy Saturday. See every complaint from anyone about the “stifling traditionalism” of their childhood since and contextualize accordingly. This upbringing proved the basis, unsurprisingly, for both his savage assaults on religion and order and his strangely affectionate taste for ritual.

Then a move to the comparative metropolis of Saragossa, where sidewalks were sheer mud, bells would toll continuously on death days (continuity!), and the “most exciting newspaper headlines tended towards ‘Woman Faints, Felled by Fiacre.’” Plenty was still very, very strange. That enormous rat was presumably still scampering around the birdcage. One Holy Tuesday, en route to beat the drums (again, some things never change) Buñuel ran into a “bottle of a cheap and devastating cognac known as matarratas, or rat killer” and proceeded to vomit during mass. Buñuel’s time for Catholic schooling was not long. On to the local public high school, “Reading Darwin’s ‘The Origin of Species’ was so thrilling that I lost what little faith I had left (at the same time that I lost my virginity, which went in a brothel in Saragossa).”

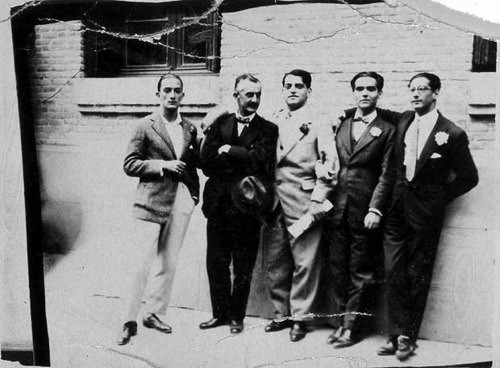

In Madrid, 1926. From left: Salvador Dalí, Moreno Villa, Luis Buñuel, García Lorca, and Jose Antonio Rubio Sacristán. (Via.)

A move to Madrid soon brought Buñuel into the company of García Lorca and Dalí (“we used to call him the ‘Czechoslovakian painter,’ although for the life of me I can’t remember why”). With the change in setting comes a reminder that, as a form, Surrealist autobiographies tend to offer perhaps the highest-voltage company of any kind.

It’s impossible to describe the daily circumstances of our student years — the meetings, the conversations, the work and the walks, the drinking bouts, the brothels, the long evenings at the Residencia. Totally enamored of jazz, I took up the banjo, bought a record player, and laid in a stock of American records. We spent hours listening to them and drinking homemade rum. (Alcohol was strictly taboo on the premises. Even wine was forbidden, under the pretext that it might stain the white tablecloths.) Sometimes we put on plays; even now, I think I could recite Zorrilla’s Don Juan Tenorio by heart. I was responsible for inventing the ritual we called “las mojadures de primavera” or “the watering rites of spring.” which consisted quite simply of pouring a bucket of water over the head of the first person to come along.”

This ritual, he notes, proved an inspiration for Fernando Rey’s drenching of Carole Bouquet in That Obscure Object of Desire.

The question that asserts itself with increasing intensity as the work progresses, and Buñuel moves to Paris is just who he didn’t meet in these years. Spanish dictator Prima de Rivera bought drinks for Buñuel and companions in a bar. Buñuel offered directions to King Alfonso XIII. He led Americans on tours through the Prado. He developed a knack for hypnotizing prostitutes (kicked the habit after one of them died a few months later). He found Picasso personally “selfish and egocentric”) and didn’t care at all for Guernica. While working with director Jean Epstein he was appalled by the whims of Josephine Baker. Epstein noted, “I see surrealistic tendencies in you. If you want my advice you’ll stay away from them.”

***

My Last Sigh (which was written with the assistance of sometime-collaborator and virtuousic screenwriter Jean-Claude Carrière) naturally offers countless rambles and diversions. Buñuel loves bars, for one, and accordingly, “the subject of drinks, about which I can pontificate for hours.” His favored drink: red wine. But never drink that in bars. “To provoke, or sustain, a reverie in a bar, you have to drink English gin, especially in the form of the dry martini. To be frank, given the primordial role played in my life by the dry martini, I think I really ought to give it at least a page.” He does just that, not to mention offering his recipe here — as he also does in The Discreet Charm of the Bourgeoisie.

A product of these gin-soaked reveries? The idea of casting two actresses in the lead role in That Obscure Object of Desire, for a start. And that’s not all on the topic of drink:

After the dry martini comes one of my own modest inventions, the Buñueloni, best drunk before dinner. It’s really a takeoff on the famous Negroni, but instead of mixing Campari, gin, and sweet Cinzano, I substitute Carpano for the Campari. Here again, the gin — in sufficient quantity to ensure its dominance over the other two ingredients — has excellent effects on the imagination. I’ve no idea how or why; I only know that it works.

Inspiration is not built on gin alone, however; there are also dreams.

During sleep, the mind protects itself from the outside world; one is much less sensitive to noise, smell, and light. On the other hand, the mind is bombarded by a veritable barrage of dreams that seem to burst upon it like waves. Billions of images surge up each night, then dissolve almost immediately, enveloping the earth in a blanket of lost dreams. Absolutely everything has imagined during one night by one mind or another, and then forgotten…

These dreams are frequently repetitive and familiar; falling off a cliff, facing an exam for which he’s unprepared, facing an audience for which he’s unprepared. (Even Surrealists, it turn out, have these dreams!) In one, a dead cousin reappears without explanation (reprise in Discreet). A church altar pivots to reveal a secret stairway.

And then his “waking dreams” which are a good deal stranger. He drugs the wife of King Alfonso XIII of Spain and, once she’s fallen asleep, “I slip into her royal couch and accomplish a sensational debauching” (inspiration for Viridiana here — also… uhhhhhh). In another, he gives Hitler an ultimatum to execute “Goering, Goebbels, and the rest of his cohort.” Unseen, he watches Hitler rage at this demand. He assassinates Goering, and then travels to Rome to give Mussolini the same ultimatum. “In between, I slip into the bedroom of some gorgeous woman and sit in an armchair while she slowly removes her clothes.” Of course.

***

The genesis of Un Chien Andalou, the short silent film he made with Dalí in 1929, is probably already familiar; from Buñuel’s vision of a razor blade slicing through an eye and Dali’s of a hand crawling with ants (what, haven’t you ever been involved in a collaborative project before??). Their only constraint, “No idea or image that might lend itself to a rational explanation of any kind would be accepted.”

Filming was brisk, but, in fact, with Buñuel, it nearly always was; his films play with the imagination with wild abandon but not their budgets; as a practical filmmaker, Buñuel was more of an Eastwood than a Gilliam. “Dalí arrived on the set a few days before the end and spent most of his time pouring wax into the eyes of stuffed donkeys.” Around this time, Buñuel was introduced to the Paris surrealist circle, “at their regular cafe, the Cyrano, on the Place Blanche, where I was introduced to Max Ernst, André Breton, Paul Éluard, Tristan Tzara, René Char, Pierre Unik, Yves Tanguy, Jean Arp, Maxime Alexandre, and Magritte.” Man Ray had already praised Un Chien Andalou to the circle, and the premiere, soon after, attracted Le Corbusier and Jean Cocteau.

What followed was a heady period of determined Surrealism, containing “so many surrealist capers that it’s difficult to decide which to describe.” You can find out about those on your own. “For the first time in my life I’d come into contact with a coherent moral system that, as far as I could tell, had no flaws. It was an aggressive morality based on the complete rejection of all existing moral values.”

The following years involved dizzying shifts in occupation; work for MGM in Hollywood, a job supervising Warner Brothers dubbing in Madrid, tumultuous years during the Spanish Civil War (he advised García Lorca not to go to Granada); a job for the Republican Spanish ambassador in Paris. Work for the Museum of Modern Art in New York arranging Anti-Nazi propaganda (and also editing Riefenstahl prints). A move into Alexander Calder’s apartment; the sight of Leonora Carrington proceeding, during a party, to slip away to take a shower in her clothes and emerge dripping wet. More Warner Brothers dubbing in Hollywood (the note that he suggested the image of a disembodied hand moving through a library in Peter Lorre’s “The Beast With Five Fingers.” And then, in the space of 18 years, making 20 films in Mexico. Diego Rivera taking potshots at passing automobiles (Buñuel, too, loved guns. He relates first facing down bullies at age 14 with a pistol — Surrealists, early enthusiasts for armed deterrence).

And along the way, endless pronouncements.

On the press:

Reading a newspaper is more harrowing than any other experience I know. If I were a dictator I’d limit the press to a single daily paper and a single magazine, and all news would be strictly censored although opinion would remain completely free.

On blind people:

Now, like most deaf people I don’t much like the blind. One day in Mexico City I was struck by the sight of two blind men sitting side by side, one masturbating the other…. Jorge Luis Borges is another blind man I don’t particularly like…. Whenever I think of blind men, I can’t help remembering the words of Benjamin Péret, who was very concerned about whether mortadella sausage was in fact made by the blind. I find this less a question than a statement and containing a profound truth at that. Of course, some might find that relationship between blindness and mortadella somewhat absurd, but for me it’s the quintessential example of surrealist thought.

And what about Surrealism itself?

I’m often asked whatever happened to surrealism in the end. It’s a tough question, but sometimes I say that the movement was successful in its details and a failure in its essentials. Breton, Éluard, and Aragon are among the best French writers in this century; their books have prominent positions on all library shelves. The work of Ernst, Magritte, and Dali is famous, high-priced, and hangs prominently in museums. There’s no doubt that surrealism was a cultural and artistic success; but these were precisely the areas of least importance to most surrealists. Their aim was not to establish a glorious place for themselves in the annals of art and literature, but to change the world, to transform life itself. This was our essential purpose, but one good look around is evidence enough of our failure.

Needless to say, any other outcome was impossible.

Buñuel’s later decades take up, curiously, the least amount of space in the volume, although those, too, are packed with incident and interest. Recall, of course, Marshall McLuhan’s appearance in Annie Hall? Originally a role intended for Buñuel. All of it tremendous fun, but bookended, in this autobiography written, in his 82nd year, by a harrowing grasp of aging, at a point when Buñuel had not been to the movies in four years and stricken by repeat problems of health, was “only happy at home.”

It was in awareness of his own “Last Sigh” that he offered this, on the one thing that really matters: “You have to begin to lose your memory, if only in bits and pieces, to realize that memory is what makes our lives. Life without memory is no life at all, just as an intelligence without the possibility of expression is not really an intelligence…. Without it, we are nothing.”

You might also enjoy: David Bowie’s Forgotten, Campy Berlin Gigolo Movie

Anthony Paletta is a writer living in Brooklyn. He has written for The Wall Street Journal, Metropolis, The Daily Beast, Bookforum, and The Millions on urban policy, historic preservation, cinema, literature, and board wargaming. Previously for The Awl, he’s written about Soviet architecture, the preservation of Brutalism, David Bowie’s campy Berlin gigolo film and the screenplays of Tom Stoppard.

New Bird Flu Claims First Human Victims, Blogs Blame It On Dead River Pigs

“H7N9 bird flu is considered a low pathogenic strain that cannot easily be contracted by humans,” the AP reports from Beijing. Well that would be very comforting for humans (if not for birds), except for the sad fact that the wire story is about the first two humans known to be killed by H7N9. Another infected human is in critical condition.

But it’s supposedly a low-level virus and not the SARS kind of crazy — that virus jumped to humans from a weird kind of wildcat cruelly captured and then kept in cages to sell to bad people at markets. SARS eventually killed 775 of the 8,000 infected during that 2003 mini epidemic.

One annoying thing about Science is that it doesn’t always “connect the dots” the way the world’s bloggers are quick to do:

Many users of Chinese microblogs, known as “weibo”, said they suspected the latest outbreak of bird flu was related to more than 16,000 pig carcasses recently found dumped in rivers around Shanghai.

Why are the Red Chinese covering up the zombie river pig bird flu conspiracy?

Photo by Jimmie.

Beloved Bronx Zoo Gorilla Dead At 40

“She was once celebrated as ‘the Shirley Temple of the animal world.’ She was so popular that she became the subject of a custody battle between two competing zoos. When she suffered a broken arm, rapt New Yorkers followed every twist and turn of her convalescence. Her name was Pattycake, and she was the first gorilla born in New York City. She died on Sunday at the Bronx Zoo at 40 years old.”

— Raise a banana to Pattycake, the sweetheart of the Bronx Zoo and the first native New Yorker of her species. She’ll be replaced by somebody with a graduate degree and a part-time blogging job looking for cheaper rent and a “fresh scene.”

Photo by Rich Brooks.