The World Roger Ailes Made

Lucky him, he doesn’t have to live in it anymore.

If you’re looking for someone to encapsulate the legacy of Roger Ailes, who died this morning at the age of 77, Slate’s Isaac Chotiner — whose interviews are currently the best in the business — has some thoughts:

When Rupert Murdoch hired Ailes to create Fox News as an “alternative” to the mainstream media, Murdoch’s intention was clear. He wanted to degrade American society in precisely the way he had degraded British society. And when degradation is your goal, there is no better hire than Roger Ailes. Ailes was a political aide turned television genius who emanated anger; his crucial insight was that there was a great amount of money to be made off the resentments of others. And the more you could stoke those resentments, the more money you would earn. At the same time, you could increase the net amount of resentment, and create a coarser society, all the better for your own pocketbook.

There is also this sweet remembrance from Awl pal Ken Layne.

They’re both at peace now.

I think that’s enough space to take up with Roger Ailes.

Every Color Of Cardigan Mister Rogers Wore From 1979-2001

Work uniform goals

While y’all were watching the world fall apart this week, I was watching Fred Rogers build it back up. For the past few days I’ve been transfixed by the “Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood” marathon that began on Monday afternoon over on Twitch. Like watching the “Joy of Painting” with Bob Ross, zoning out to “Mister Rogers” is an exercise in escapism. After Rogers helped reset my brain I began to wonder about all the handsome, colorful sweaters he famously wore. Did Rogers have a favorite?

Fortunately, Tim Lybarger, a 40 year-old high school counselor from just outside of Champaign-Urbana, Illinois, wondered the same thing a few years ago. Back in 2011, on his blog devoted to all things Mister Rogers, neighborhoodarchive.com, Lybarger recorded the color of every sweater Rogers wore in each episode between 1979 and 2001. “When I realized such a resource didn’t exist,” Lybarger told me over email, “I just felt like somebody needed to do it…might as well be me.”

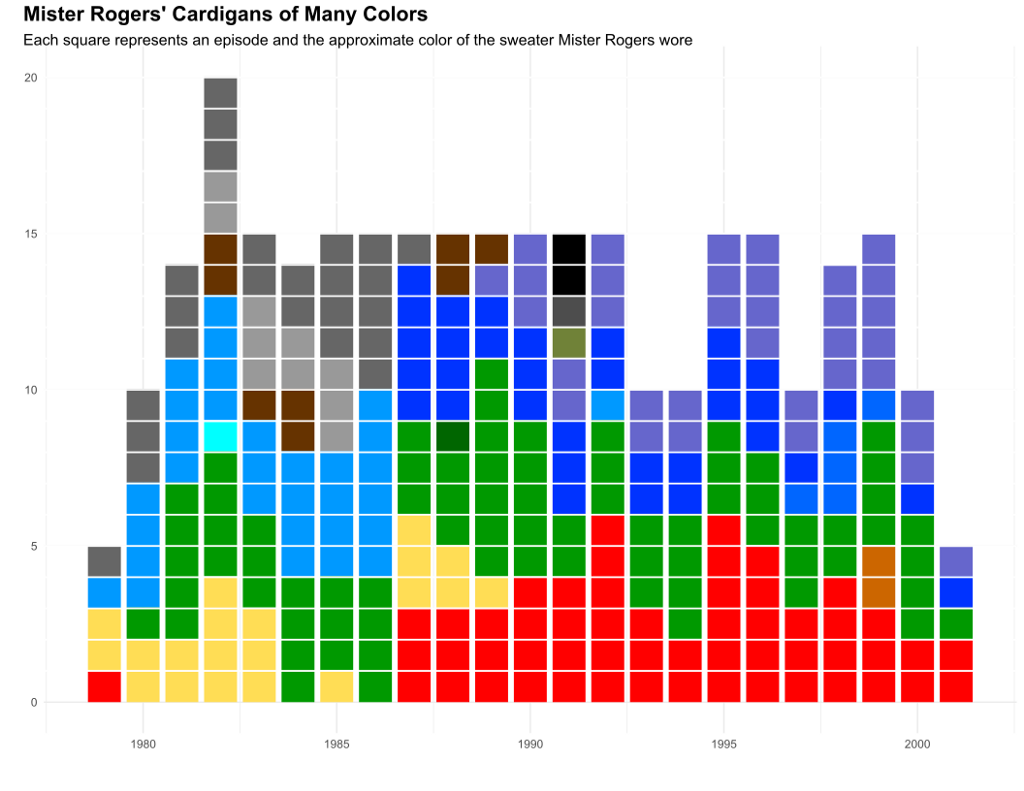

The chart below uses the data Lybarger meticulously collected to show how Rogers’ preferences for the color of his cardigan changed over time.

Each square represents an episode and the approximate color (designers don’t @ me) of the sweater that Rogers wore. There were three episodes during this stretch when Rogers went without a sweater.

Some sweaters were worn once and then never again, like the neon blue cardigan Rogers wore in episode 1497. Others, like his harvest gold sweaters, were part of Rogers’ regular rotation and then disappeared. And then there were the unusual batch of black and olive green sweaters Rogers wore exclusively while filming the “Dress-Up” episodes in 1991. To this day, members of the Neighborhood Archive message board claim those are the only sweaters Rogers wore that were store bought. The rest were hand knit by his mother.

As a ’90s kid, I associate Rogers with his red cardigan more so than any other sweater, so it was surprising for me to see that green is actually the color he favored the most — edging out red by a total count of 74 to 54. It turns out though, Rogers was red-green colorblind, so I like to think that some punk PA was messing with him and told Rogers they were both different shades of brown.

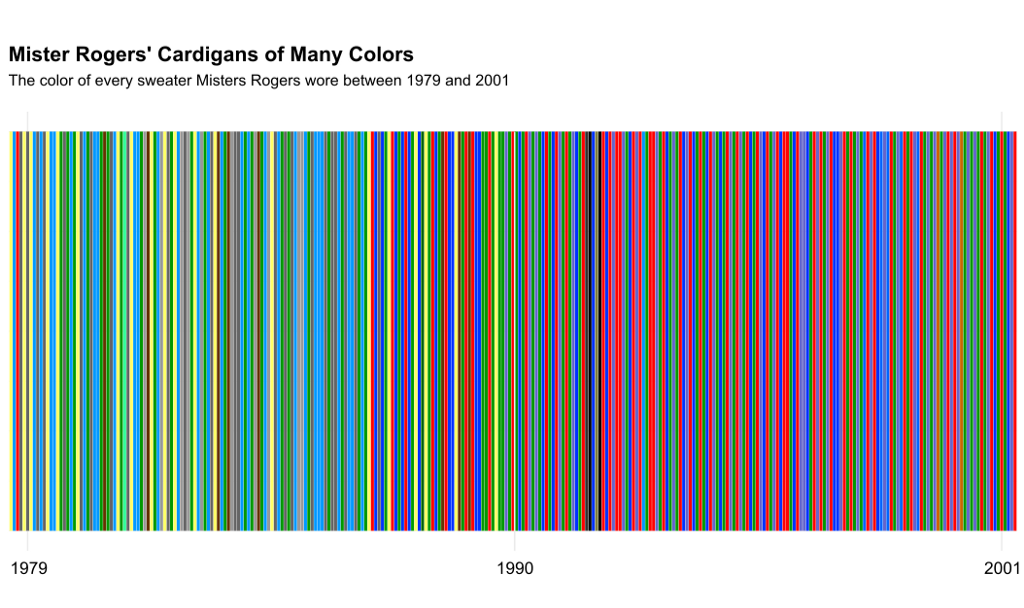

A noticeable pattern also shows up when you lay out the color of each sweater Rogers wore chronologically: Over time, Rogers ditched the pastels for darker, more saturated tones.

Before every Urban Outfitters in the world was stocked full with cardigans, Rogers made them his signature accessory. His fashion-forwardness should inspire Mark Zuckerberg, the modern poster boy of the “work uniform” movement, to try and dress a little less like a fuckmook.

The code used in this analysis can be found here.

(Ed. note: Fred Rogers’s questionable ess-less possessive has been honored throughout.)

Rodriguez Jr., "Baobab"

Everything’s next.

It has been a hell of a morning already and you are no doubt tensed and waiting for whatever is going to happen to us next, which I guess is the permanent condition in which we will now spend the rest of our lives, however long those are. Perhaps this will help you unwind for the few minutes you have in between astounding new developments. Enjoy.

Chris Cornell, 1964-2017

And now he’s dead.

Here’s the Soundgarden song that meant the most to me. What’s yours?

New York City, May 16, 2017

★★★★★ People sat out on their east-facing balconies. The warmth was not quite manifest under the scattered morning light, but the anticipation was there. There were shorts out in late morning, a sleeveless undershirt, a romper, a shirtdress. A man sat outside a building with his sleeves turned back to show purple inner cuffs. Another man wore a short-brimmed straw hat. Even into the afternoon, though, the general public held back, wary after the long chilly days, their summer dresses and t-shirts chaperoned by cardigans and jean jackets. Union Square smelled a little bit like sweat and a little bit like greenery. Some gray gathered in the west, then pulled apart in glowing furrows, which expanded into blue stripes. Out on the engineered grass roof at Lincoln Center, some mushrooms had sprouted. The clouds slid overhead, their ranks breaking up, their color now a blurry white and silver. The children ran in circles playing tag one-on-one, the younger in his socks on the grass, the elder still in shoes.

Yes, Trump Is Dumb, But Is Trump Actually Smart?

What if this imbecile is really a genius?

You’re rolling your eyes right now but wait long enough and they’ll come back to this one. It’s only a matter of time.

How's it Going?

Deutschland über us.

The home page of the German newspaper Die Zeit contains a poll, as websites of the internet are wont to do. But there’s a twist! Instead of asking what the polls ask us in America (DO YOU TRUST OBAMA??!!) and then clicking us off to what definitely seems like a legitimate internet place that I’d like to give my email and other pertinent information to, this poll is commissioned by Die Zeit itself, and asks but one question:

Wie geht es Ihnen heute?

This query — pronounced vee GATE ess EE-nun HOY-tuh—may be familiar to anyone who has ever gone to the first day of German 101 and then had the Hose scared off them; colloquially it means “How are you today?” but literally it means “How goes it with You (the Formal ‘You’ I Don’t Know Very Well Or Who Works In a Bank) today?”

As in our culture, it is often the first thing German-speakers say when they greet each other, after Hallo or Guten Tag (or, in Austria, the excellent Servus). Pals use the informal Wie geht’s dir? and many people often abbreviate it to Wie geht’s? If you want to sound like a dork who definitely isn’t a native speaker, you can do the thing that I for some reason blurble up every fourth time I greet a German friend: Wie geht’s/wie steht’s? (vee GATES, vee STATES?). And if you want to sound like Joey from German Friends, you say: Na…wie GEHT’S denn so?

So, we’re all good on the question part. Germans, like Americans, enjoy asking each other how it’s going. CULTURAL SIMILARITY!

Here’s where it gets different. When Americans ask this question, they mean I definitely don’t care and I’m going to stop talking to you in approximately 20 seconds. When Germans ask this question, they don’t necessarily demand honesty, but they certainly won’t be surprised if that’s what they get. Indeed, I haven’t done a peer-reviewed scientific survey or anything, but I’d say the most common answer to Wie geht’s is Na ja…es geht (NA YAH, ess GATE), which basically means What the fuck ever, I’m still alive, and is definitely not how you want to answer the lady at the snack stand in 1997 if she asks you if you want ketchup with your fries, she said for no reason. (“Zat…was wrong,” laughed my friend Christoph, and then he laughed and laughed and laughed some more. I GET IT CHRISTOPH, I FUCKED UP. JEEZ.)

Here is a list of acceptable answers to the American question “How’s it going?”

1. “Great!”

In German, on the other hand, just about anything goes. Indeed, the only thing you can’t answer to Wie geht’s is ich bin gut, which literally translates to “I’m good” but actually means I am a very good person, you bastards. Whereas even accomplished grammarians such as myself regularly substitute, in English, in the adjective good for the adverb well because it’s colloquially accepted to do so and anyone who answers I am well is an insufferable pedantic fuckface, German grammar is (I think I’m gonna have a heart attack and die from nicht-Überraschung) somewhat more stringent.

To wit: the Ihnen and dir in Wie geht’s are in the dreaded dastardly Disney villain of cases, the Dative; the way you answer in full (and the reason many German 101 students hotfoot after day eins), is Es geht mir [adjective of your choice], or, if you’re being schmancy, Mir geht’s [a descriptive thing]. That means, technically “It goes [well/poorly/apocalyptic] to me,” and the dative construction signifies the ephemeral, almost Buddhist, state of one’s emotions; “it” goes with you in whatever way “it” will.

So, in German you can’t say you “are” anything (gut, schlecht, lebensüberdrüssig, schadenfroh), but you can definitely say you are feeling whatever the hell you are actually feeling, and your convo partner will not pull a face and then make a lengthy series of Tweets about Toxic Negative People In Her Life.

The German propensity for blunt honesty — and our own propensity for Being Positive even when our Republic is engulfed in a grease fire that people keep dumping water on and then going Don’t tell me not to put water on a grease fire, you elitist libloser — is what leads to statistics such as the World Happiness Report, which claims Americans are the 14th-happiest people in the whole world and Germans merely the 16th-happiest, even though they have ubiquitous bike paths and eight weeks of paid vacation a year and we have open treason in the highest office of the land, and Chicago Med.

AND YET. The Zeit poll’s results? Somewhere around 70 percent of its respondents over the past two months and counting say “it” is going gut. (The project of which this poll is a part has been active since March.) And Zeit readers are among Germany’s more intellectual (and thus grumpier), so if anything the sample is biased toward the crotchety.

Once you answer the poll, you’re then prompted to give a one-word description of your mood, and the Zeit runs a scroll of some of the responses it gets over a 24-hour period, divided into “good” and “bad.” They run the gamut from frischverliebt (FRISH-fur-LEEBT, or newly in love!) and zukunftsfreudig (TSOO-koonfts-FROY-dig, or happy for the future — jeez really?) on to arbeitsüberlastet (ARE-bites-oo-bur-last-et, or overwhelmed with work) to the somewhat redundant schlechtgelaunt (SHLEKT-guh-LOUNT, or in a bad mood).

As you can see, the Teutonically honest full range of human fee-fees is there (as well as a full list of common ailments, from Grippe, or flu, to Rückenschmerz, or backache) — but still. Seventy percent of those emotions (or lack of ailments) are positive. Germans, however dour they might seem when you’re talking to them, are happier than they sound.

But why? Are Germans like Gen-Xers, where it’s only cool to be miserable and hate everything, so they’re only comfortable revealing their secret opposite-of-shame on anonymous Internet surveys?

Are Germans the opposite of internet trolls? Or is it something even more nuanced than that, where the sort of blunt, unsmiling default es geht state is its own sort of happy? Americans are certainly better at being fake-happy — I once had to give a fake-happiness tutorial in Austria for my friends who were about to move here—but maybe real happiness has more room for, you know, scowling and telling everyone you’re having a shitty day.

Of course, this also could all be moot, and the Zeit poll’s surprising results could also just be due to the heinous bias of the survey: Shockingly, there’s no response bubble for na ja, es geht.

BONUS!!! Hey, we can do it too! Please answer this very important question.

The Joys of Texting Myself

It’s very satisfying.

My friend Nicole keeps track of her favorite public bathrooms by texting herself. Genius, I thought. Convenient, simple, obvious! Delightfully self-reflexive! That was the first I ever heard of texting yourself, and I felt like I’d been let in on a big secret, maybe even the ultimate Hack, but without the binder clips and toilet paper tubes appearing where they don’t belong.

The best self-texting scenarios seem practical at first: Why not use a thing you already open five thousand times a day to quick-jot notes and reminders? It’s like having a notebook in your pocket, minus the pen, and even less complicated than Notes. The process is simple. But like most simple things, it’s deceptively straightforward, and the real benefits only surface after a few rounds.

Here’s how it works.

Get an iPhone. Open up a new text, type your number in the To: field, then text yourself. Say anything. The first thing I wrote myself, a few months after learning about this technique was “Alley cat vintage anacortes” because I promised a lady in Anacortes, Washington I’d call back about a dress (I didn’t call back).

In response to your text, a bubble with the same message appears: “Hi, Hi.” It takes a solid beat or two on the iPhone, but it always appears. It’s a very satisfying process.

It’s possible to communicate with yourself on other devices and platforms, but none feel rewarding in quite the same way. Most androids allow for self-texting, but the response appears instantaneously, extinguishing a bit of the magic. WhatsApp is the purgatory of self-texting: it allows you to text yourself, but there’s no response, just the weird specter of you, typing… which lasts way beyond the time you’re actually tip-tapping. The phone app for gchat allows you to find yourself, but then says “couldn’t create conversation” and marks your attempt with a scary red-circled exclamation point, as if you’ve transgressed. The email-bound version of gchat won’t even let you attempt a conversation. Slack, on the other hand, encourages self-chat as a way to organize documents and notes — probably because it was borne of email, where people are more used to sending documents and reminders to themselves. That’s about practicality, I think, and most people who text themselves consider it a practical act, not a joyful or a personal one.

A small but very scientific survey shows that about two percent of the people I talked to last week text themselves, and zero percent do it regularly.

After I asked, two friends tried it for the first time ever. Sara Beth texted herself “Remember to bring home all Deb’s presents. Outfit for Saturday & comfy clothes.” She emailed me the screenshot. I love Deb, I responded. Tell her HBD. Will Sara Beth continue texting herself? Unlikely. In fact, she’s more likely to text a friend the same info and request a reminder, she claimed, adding #thisisthirty.

Ben, sitting next to me at a bar, wrote “Remember never to hang out with Rachel and Brian ever again,” and was freaked out by seeing his own name appear. I said, But isn’t it great?! and tried to describe how seeing yourself doubled can actually be freeing, how the initial repulsive recognition can give way to a surprising sense of comfort. He disagreed, and says he plans to stick with emailing himself.

Two friends had used it in the recent past, but probably won’t anymore. My friend Ellen self-texted several times when she was dating. “Test” she’d text, to make sure her phone was indeed operable and open to signals. Seeing “Test” repeated back must have been infuriating, but it’s hard not to admire the way Ellen recognized an opportunity and wasn’t scared to face herself, or her worst nightmares.

Chris responded to my question with surprise, saying, Yes! Just last night. He followed up with a screenshot (“Whiplash, Whiplash, Huh, Huh”) and told me he was marvelling at how weird it looks. He described it as synthetic and slightly eerie, a glitchy aesthetic but without the glitch. Like vaporwave, he said, and sent me a song called “Andro” by Oneohtrix Point Never that was truly freaky, partly because it’s from an album called Replica, but doubly freaky because there’s a chatbot, also called Replika, that was originally designed to recreate conversations with a dead friend.

There are thousands of color-coded, supportive, alert-filled organizational apps designed to dance circles around a simple text. A text can’t really be organized or remind you of something if you don’t go looking for it, but that’s the best part. It’s weirdly rewarding to use a complicated instrument for simple things, as if debasing its intelligence will somehow confirm your own, or at least delay the inevitable judgement: your TI-89 calculator is smarter than you, but at least you can draw boobs with it while you come to terms with reality.

The simplicity of the whole operation — like in gives like out — seems to magnify the value of texting yourself. Plus, it feels like a dark back-channel convo, a tricky diary that no one reads except Verizon or AT&T, or your nosy partner. No rules.

I texted myself a full dream the other day, and no one stared blankly at me or texted back “That’s weird.” When the dream repeated itself to me in butterflied fragments, it actually sounded better, because I am in fact the best audience for my dreams. “The waves were white and deep blue, The waves were white and deep blue, I never went in the water, I never went in the water.”

I’ve also used the self-texting mechanism to hold a full conversation with someone else, sitting right next to them. This amplified the sense of self-confirmation into a drone-shaped therapy session: “My babe, My babe, You are so wrong about your hair, You are so wrong about your hair, It’s beautiful, It’s beautiful, I love you, I love you.”

Later that night, in the bathroom by myself, I texted “I’m dying,” and it came back coldly comforting, like a pat on the shoulder. “I’m dying.”

Long before all this, back in the first few months of self-texting, I was pleasantly drunk and wanted to remember the name of the internet dog, so I texted myself “Shiba Inu.” The response appeared, reliably. I had the same reaction as Chris’ “huh,” which is kind of like the unstoppable desire to say “echo” into the void (suddenly I understand Amazon) but I wanted a bigger twist, so I wrote “Is that you in the bathroom, texting?”

Drunk timing made the waiting beats last even longer, and I sat frozen, alert for a confirmation that I existed. It came. “Is that you in the bathroom, texting?”

“Yep, it’s me, Yep, it’s me.”

Rachel Miller lives in Ridgewood and used to collect stamps.

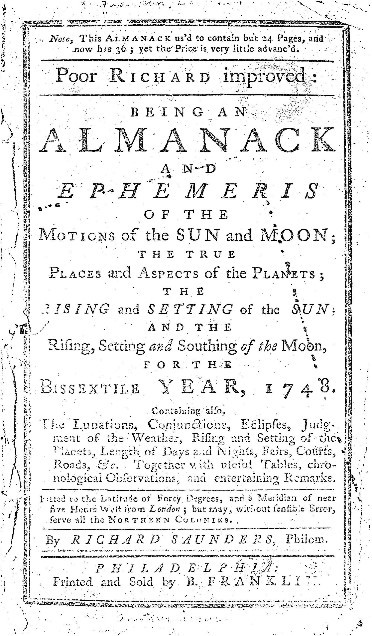

Do As Poor Richard Says, Not As He Does

From whom, how, and why Benjamin Franklin plagiarized his famous proverbs

To modern Americans, Benjamin Franklin is one man but many characters. Like the boyfriends of television ingénues, everyone has a favorite. Some prefer the polymath Franklin, the nutty scientist who invented the lightening rod. Others prefer Franklin the patriot, the oldest signer of the Declaration of Independence. Then there is Richard Saunders, perhaps the most popular Franklin of all. Conjured from the oft-quoted proverbs he published in Poor Richard’s Almanack between 1732 and 1758, this Franklin strikes the image of a sagacious but folksy old man: America’s own Confucius.

Poor Richard’s proverbs are, and have been for centuries, a part of the American canon. We identify them not only with Franklin’s literary talent, but also with a unique colonial-American slant on Enlightenment-era philosophy. Widely celebrated, this association ignores two inconvenient truths. Poor Richard’s sayings were not American, and for the most part Franklin didn’t write them.

“Franklin took British aphorisms and adapted them in the style of ‘Richard Saunders’ for the American provincial audience of his almanacs,” says George Goodwin, author of Benjamin Franklin in London. “Thus Daniel Defoe’s ‘Things as certain as Death and Taxes, can be more firmly believed’ became ‘In this world nothing can be said to be certain, except death and taxes’ and what had been British became American.”

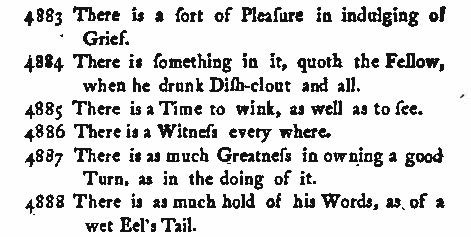

Among other sources for his sayings, Franklin borrowed greatly from Thomas Fuller’s Gnomolgia (1732), George Herbert’s Outlandish Proverbs (1640), and an anonymous Collection of Epigrams (1737) — all published in England. That he mined these books for material is neither surprising nor inherently scandalous. As a citizen of a British colony, he took immense pride in the comedic sensibilities of his motherland. More importantly, as an eighteenth-century publisher, he considered the inclusion of unattributed knowledge well within the bounds of fair use. “Writers [back then] didn’t have the modern sense of plagiarism that today’s professors pound into the heads of our students,” says George Boudreau, history professor at La Salle University. “There was certainly no shame in lifting someone else’s words or ideas, whether it was for a personal letter, a newspaper article, or a government document.”

Indeed, Franklin never denied lifting Poor Richard’s proverbs. In his classic essay, “The Way to Wealth,” he admitted that “not a tenth part of the wisdom [in the almanac] was my own…but rather the gleanings I had made of the sense of all ages and nations.”

Some historians believe Franklin sold himself short with such talk. His skillful edits rescued countless proverbs from a cross-generational rubbish bin, which now brims with outmoded eighteenth-century wit. “Franklin,” historian Jill Lepore once wrote, “was the kind of literary alchemist who could turn drivel into haiku.” Under his pen, “A man in Passion rides a Horse that runs away with him,” became, “A man in a passion rides a mad horse.” Likewise, George Saville’s clumsy “To understand the world, and to like it, are two things not easily reconciled,” became the much snappier, “He that best understands the World, least likes it.”

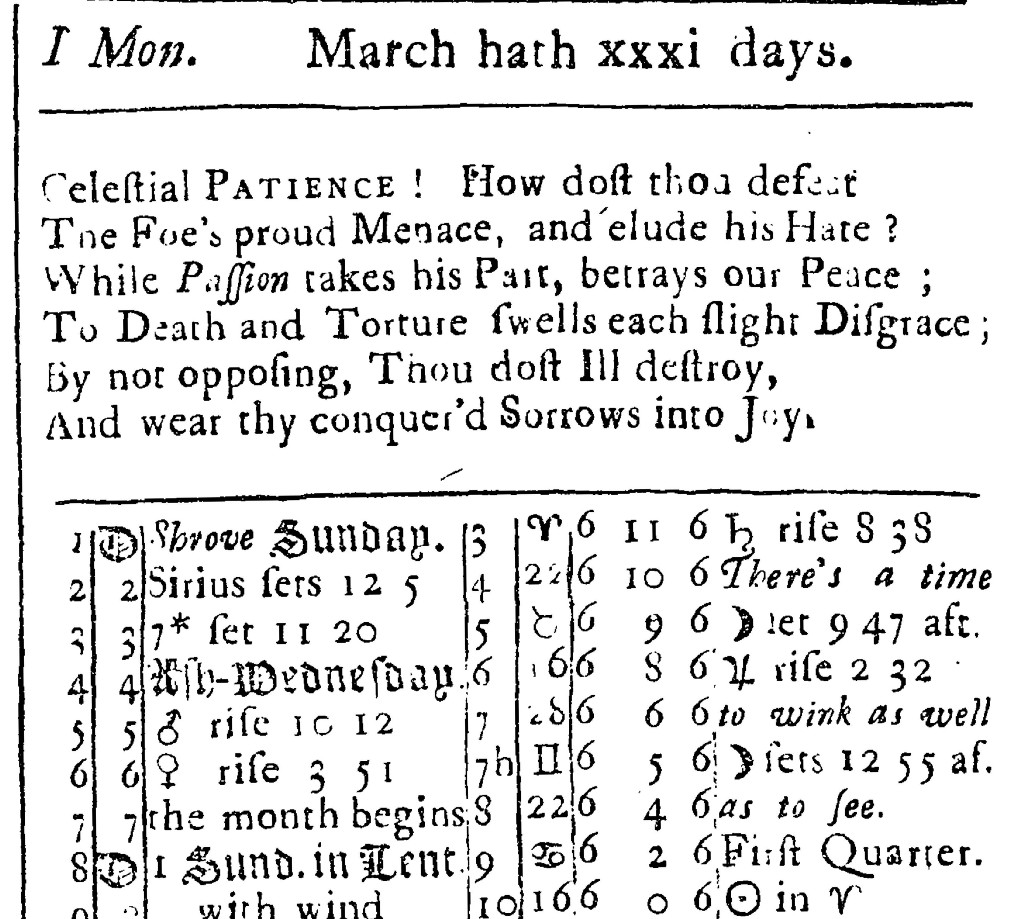

As to why Franklin chose to pilfer, polish, and publish Poor Richard’s sayings in the first place, their original presentation in his almanac provides a few clues. “People then looked at [almanacs] like people today look at Google,” says Boudreau. “They had government meeting dates and sessions of courts; celebrity gossip in the form of when the king, queen, and royal family celebrated their birthdays; and [other] ‘useful knowledge’. Franklin’s little sayings were entertaining, witty, logical, empowering. But look at how little page space they got.”

While we now consume Poor Richard’s proverbs on numerical lists of Franklin’s greatest hits, his contemporary audience encountered them amid charts, which detailed water tides, moon phases, and the rising and setting of the sun. Franklin printed his proverbs within the seventh and final column on the right-hand side of these charts, under a section entitled “the Changes of the Moon.” This required him to break one “saying” into multiple parts, often in two or three word spurts. This could explain why he did not hesitate to lift material from Fuller, Herbert, and others: Poor Richard’s aphorisms were literally space fillers. When presented with problematic rows, Franklin rifled through his sources, located the choicest proverbs, then either placed them where they fit in naturally or parred them down as necessary. Thus, “A Father is a Treasure, a Brother a Comfort; but a Friend is both” became “A father’s a treasure; a brother’s a comfort; a friend is both.”

Perhaps it is permissible, then, to forgive Franklin for participating in the rampant plagiarism that defined his era in publishing. After all, his thievery helped enliven yet one more character for colonial America’s man of many faces: Franklin, the frugal capitalist. As Poor Richard himself once wrote, “Necessity never made a good bargain.” So why waste money on a simple margin problem, when a nearby bookshelf offered a free and easy fix?

Daniel Crown writes about history and books.