Superstar Eccentric Nathan Rabin On The Magic Of Phish And The Glory Of Insane Clown Posse

by Janet Potter

Nathan Rabin is a staff writer at the forthcoming site The Dissolve, which was formed with Pitchfork from the mass exodus from The A.V. Club, where he was head writer. Back in 2010, Rabin set out to write a book about Phish and Insane Clown Posse, two bands who are as ignored by the mainstream music world as they are adored by their fans. He followed Phish on tour that summer and then went to the Gathering of the Juggalos, ICP’s annual 4-day festival, finding both experiences to be intriguing but less than affecting.

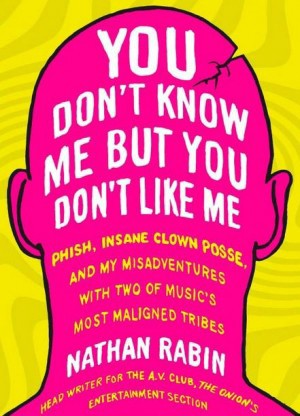

Then, as they say, everything went wrong. Rabin went broke, lost a year’s worth of writing, and started to wonder if he was going crazy. So he did it all again. The summer of 2011 found him back on the road with Phish and at the Gathering. Wouldn’t you know it, music saved his life. “I need more things in my life with completely intangible value,” he wrote in his resulting book, You Don’t Know Me But You Don’t Like Me — and what he found that year were community, salvation, and joy.

You Don’t Know Me But You Don’t Like Me is both a perceptive and funny introduction to the communities that surround two bands, as well as being a candid and moving memoir. We talked about music, fandom, and escape over email.

Two words that come up repeatedly in your book are joy and vulnerability. In the journey that you chronicle in this book, your experiences of both seem to parallel each other. Can you talk about how they’re connected?

Sure. The first year that I worked on the book I was crippled with self-consciousness. I am someone for whom writing comes naturally. But I could not get anything out of my experiences that I could use in the book and that’s because there was a barrier between me and what I was writing about. I couldn’t find an entryway into this world that I desperately wanted to explore, so that contributed to my self-consciousness and my sense of pessimism and doom that I’d never finish the book, which in turn further fueled my self-consciousness. It was a vicious cycle.

You Don’t Know Me but You Don’t Like Me: Phish, Insane Clown Posse, and My Misadventures with Two of Music’s Most Maligned Tribes is available through many places, from among which you may choose using whatever moral and financial calculus you generally use to purchase books:

• Powell’s

• Amazon

In addition, he may be appearing near you.

It wasn’t until the world had rendered me vulnerable by stripping away all my defenses and putting me in a state of complete openness and hyper-sensitivity that I was able to really experience the joy that was the key to the book: finding the transcendence that is the ideal of both the Juggalo and Phish experience, that sense of togetherness and brotherhood and living in the sacred present tense instead of obsessing about the future or the past. I had to experience that joy, and know that it existed and was the reason I had set out on that strange journey in the first place, in order to feel like I had cracked the mystery of the book, and I never would have experienced it if I wasn’t in such a vulnerable place. Defenses are supposed to protect us. They often serve an essential function but they can also separate us not just from other people — in this case Juggalos and Phish fans — but also from ourselves. At the beginning of my journey I felt separated both from other people — specifically the subjects of my book — and myself and it’s because there was this distance, and this wall, this attempt at journalistic detachment that never quite took, and it wasn’t until that wall tumbled down that I was able to make myself vulnerable enough to experience pure, unapologetic joy.

You describe the atmosphere around Phish or ICP gatherings as welcoming and communal, and the people you meet are generally friendly, unironic, trusting, helpful, and generous. It struck me how different this is from how most people act on a daily basis, that we are accustomed to operate in a skeptical, closed-off way. How much of the appeal of following these bands do you think derives from finding a community that seems like a gentler version of society?

I think much of the appeal of these subcultures comes from that sense of instant connection, that if you go to a show or a festival or even see somebody with a Phish tee-shirt or a Hatchet Man tattoo there’s this automatic bond that cuts through the detachment of everyday life. Everyone is sort of expected to maintain a stoic game face as they trudge through their days, especially in a city like Chicago, where I spend a lot of my time on public transportation and everyone looks like they’re on the way to a funeral. But you go to a Phish show or the Gathering of the Juggalos and it’s very common to see people with big, child-like smiles on their faces. Sure, it might be because they’re on powerful drugs but it’s also because they’re around their favorite music and people who they feel an instant connection with because of that bond. It’s a world where strangers can smile at you without anyone finding it suspicious. And that was powerful for me particularly when I was writing the book because I felt like I was barely able to function in society, that making small talk and making it through the day was becoming unbelievably hard so I think it was incredibly life-affirming and healthy to be around people who exuded such intense positivity and excitement. It was like a bizzaro world where everyone’s default emotion seemed to be excitement and happiness rather than grim determination to get by.

I do my first reading/signing for You Don’t Know Me, at Anderson’s in Naperville at seven 2day. If your in the neighborhood, head on down.

— Nathan Rabin (@nathanrabin) June 18, 2013

It’s a signing the book store will never forget, mostly due to the lawsuit they’ll be filing against me for wanton destruction of property.

— Nathan Rabin (@nathanrabin) June 18, 2013

There will also be multiple hacky sack circles. A veritable shit show of spectacle and sensation it will be!

— Nathan Rabin (@nathanrabin) June 18, 2013

Not to bang on about society’s ills, but what do you think the connection is between people being increasingly impersonal with each other, with more and more human interactions being mediated by technology, and the decision to devote so much time, vulnerability, and emotion to a band? Do you think these bands are filling a need for human connection? Is it even possible for a band to do so?

I definitely feel like the subcultures that have come out of these bands fill the need for human connection. During the summer of 2011, when much of the book takes place, I was feeling an almost technology-induced schizophrenia. I felt detached from the physical world around me and other people and places and even my own body. So much of my life was virtual: podcasts where people I wished were my friends a thousand miles away were having deep, meaningful conversations I wished I was having myself, Twitter, where I virtually interact with thousands of people I will probably never meet but whose lives I am invested in all the same, and my iPod, where music finally and conclusively broke free of all physical entanglements and became completely technological. So to actually go out on the road and carry around a giant suitcase and ride on buses all night long and talk to actual people and see shows where Trey played guitar in front of me and five thousand fellow travelers united in a groove helped me understand that intense spiritual connection people feel to a band on a profound visceral level. It wasn’t something I hypothesized about or contemplated on an academic level: it was something I felt in my gut. The same thing with The Gathering: it’s an intensely physical, personal, intimate experience and that’s part of what makes it so special. It’s something you need to experience, it’s not something can get the gist of from a BuzzFeed slideshow.

ICP’s mythology is called the Dark Carnival, and at one point in your book you call the Phish experience a “carnival of light.” Although they inspire similar levels of devotion, and obviously you like them both, do you see a fundamental difference in their appeal and/or philosophy?

I do. I think ICP is much more of a way of life, a philosophy, a sensibility, a way of seeing the world, almost a makeshift religion, whereas I think Phish, despite the Game Henge mythology, more epitomizes the transcendence inherent in rock and roll. I feel like ICP’s appeal extends beyond music, to a whole different realm of culture. There’s also a fundamental difference in the iconography involved: Phish’s tends to be more playful and whimsical, whereas ICP famously favors the Gothic and sinister, even if there’s a lot of goofy humor at the heart of both group’s music.

Have you gotten any reaction from either of the bands or the fan communities?

I’ve heard that Violent J has read my book, but I do not know what he thinks of it. Phish’s manager had read it as well, and liked it, though he felt it focused a little too heavily on the drug/tour-rat aspect of the group’s following at the expense of its diversity. I felt like that was a legitimate criticism, though my focus had much more to do with where my mind was at the time, rather than an objective reflection of the group’s fan base, which I think I establish as being very diverse and also very well-educated and sophisticated in a lot of ways, musically and otherwise.

I had worried that the book is so personal and so intimate and so strange that people would have difficultly relating to it but I have been overjoyed to discover otherwise. While few can relate to going crazy while writing books about Phish, ICP and “Weird Al” and being head writer of The A.V. Club, I’ve gotten a lot of emails from people saying that my story echoed and reflected and commented upon their own history with Phish, that I tapped into something universal about the need for connection and transcendence and the profound bond we feel with music. That’s been really encouraging. People have been sharing their Phish stories and their Phish memories with me and that makes me feel great. I want my book to be part of a great ongoing, decades-long conversation about music and community and Phish. I’d just be happy to be a footnote to both group’s legacies. I haven’t heard much from ICP fans but hopefully that will change in the near future. If nothing else, I would like for it to be the most-read book at the Gathering this year.

Apart from the fact that you no longer have a book to write about them, do you think you’ll continue to follow these bands with the same dedication?

Definitely. If it were up to me I would spend a few weeks following Phish every summer and go to every Gathering. Financially, professionally and otherwise, that’s not really possible but I plan to continue going to the Gathering for the indefinite future and I plan to go to at least four Phish shows. Painfully enough, Phish’s 3-night run in Chicago overlaps with The Pitchfork Festival, which looks to be amazing this year. So I will have to choose between R. Kelly and Trey Anastasio. I gotta choose between my new book and my cool new job. Truly Sophie’s Choice, if Sophie had to choose between two awesome things that reflected how lucky she was and how great her life was (between the new job and the new book and my new puppy I feel very blessed).

Janet Potter is a staff writer for The Millions and blogs about presidential biographies at At Times Dull. Follow her @sojanetpotter.