Celerity Unnecessary

“Police are trying to track down an unlikely getaway driver — a man on a mobility scooter who escaped the scene at just 4mph.”

Breaking Up Is Hard To Do: Study

“Researchers interviewed 24 young people between the ages of 19 and 34, and found that digital possessions after a breakup are often evocative and upsetting, leading to distinct disposal strategies. Twelve of the subjects were deleters; eight were keepers, and four others were selective disposers.”

— What kind are you? [Related]

Watch Trailer Or Stay Pure?

At this point we are pretty much all keeping our head out of the stove until the return of “Arrested Development,” right? I am going to watch all those episodes so hard! In fact, I am not even watching this trailer, that is how fresh I would like to come to the show. But you may have a different way of doing things, in which case you should enjoy the trailer on your own time. In related “Arrested Development” news, did you know that Awl pal Will Leitch is the designated media expert on the show? Here are some other things you probably missed. See you in June, oven!

Are You Freaking Out Enough About SARS?

WHAT DO YOU NEED TO KNOW ABOUT THE DEADLY NEW CORONAVIRUS? Here’s WHAT YOU NEED TO KNOW ABOUT THE DEADLY NEW CORONAVIRUS. I mean, don’t panic or anything, it’s not a complete nightmare yet. Soon, probably, but not yet.

Don't Give The MTA That Metrocard Dollar!

In Union Square this morning. The MTA is making millions off that extra buck you pay for a new metrocard. We’ve got reaction

— kristen shaughnessy (@kshaughnessy2) May 13, 2013

Each Metrocard costs the MTA about six cents to make. Since March, they’ve charged you a dollar for each one, because it’s not “green.” Because… that’s your fault. That they make Metrocards. Yeah.

So the other 94¢ the MTA makes on each card goes to planting a baby tree in Queens. Because that’d be GREEEEEN. Just kidding, it’s all profit. The idea of this having to do with the environment is as fake as the scammy carbon credits market that Goldman Sachs invented. The unsurprising news today is that the MTA is raking it in on the new Metrocard fee. This is unshocking. Sometimes you need a Metrocard, you know? Like when you’re one of New York City’s 47 million tourists each year. (The other news is that they won’t tell anyone how much they are making on it? Because apparently they don’t have to? Until I guess their annual report?)

I haven’t bought a new Metrocard since March, even though mine is all raggedy and always looks like it’s on death’s door. I’ll pay $2.50 for a terrible bagel in midtown or $4.50 for a coffee but I won’t give those jerks that stupid dollar. Please join me. I’m gonna start giving dollars to homeless people on the subway, since that’s actually still illegal, while scamming customers in the name of the environment isn’t.

Finally, A Website About Television

“Previously.TV is a new site about, guess what, TV. We’re talking about last night’s shows, and some of the latest TV news, in the way we watch TV: a mix of appreciation, obsession, grim resolve, and abiding affection.”

— Very, very excited about Previously.tv, a new website from Awl pal Tara Ariano and a scary-talented group of contributors. I would tell you to add it to your RSS Reader, but do those things even exist anymore? DAMN YOU GOOGLE READER. Anyway, go here frequently.

Let's All Act Like We're Angry Today!

The stereotype about New Yorkers (or, you know, one of them) is that we love to complain, although as is the case with most things in life that is pretty much true of everyone everywhere — have you ever heard of a place whose tourism slogan is “The City Where No One Complains”? — New Yorkers just tend to do it more loudly and frequently plus it has a wider audience because the news and a bunch of the culture are made here. Anyway, there are a couple of days each year where the complaints — which are indeed annoying, stereotypes or not — are actually a kind of community conspiracy in which we are all ostensibly whining about the same thing but are really not so much crabby as jubilant in a way that, being New Yorkers, we only know how to express in the medium of criticism. Today is one of those days. Everyone is going to pretend to be irritated about the fact that it has gotten slightly chilly again, when, deep down, we’re all super-excited about the arrival of nice weather (drop in temperature accounted for, it will still be 60 today, which, come on, you would have been wearing shorts in weeks ago) and stupidly optimistic that this time, when the seasons change, things will actually be better. They won’t — if you were able to fast-forward to August you’d find a town full of angry, aggravated people who reek of sweat, exhaustion and defeat — but this is that tiny window where we can all kid ourselves that they might. So let’s enjoy it while we can, because there’s nothing but suck coming up on the calendar. Also, good morning! Cold out there, huh?

Photo by needoptic

May I Have Your Pantelegraph? The Ritual of Book Signing in a Digital Age

by Alan Levinovitz

I congratulate you, my dear Cornelia, on having acquired the valuable art of writing. How delightful to be enabled by it to converse with an absent friend, as if present!

— Thomas Jefferson

She hesitated, and then, impulsively, “I wonder if it would be too much to ask you for your autograph?”

Ralph then attached the Telautograph to his Telephot while the girl did the same. When both instruments were connected he signed his name and he saw his signature appear simultaneously on the machine in Switzerland.

— Hugo Gernsback, Ralph 124C 41+ (1911)

I.

On February 27th, Toni Morrison took part in an online “Hangout” hosted by Google Play, during which she video-chatted with a few lucky fans from around the country before signing their copies of Home. The cover of each person’s ebook was personalized remotely (“For ______ / Toni Morrison”), and images of the covers were posted to the Google Play page as well as Morrison’s profile page. According to Publishers Weekly, Morrison also signed paperback editions of the novel for Google employees in New York, her physical location during the Hangout.

Debate about the pros and cons of ebooks usually focuses on the relationship between a text’s significance and its medium, passing over the trivial issue of a signature’s significance. But signatures are actually an instructive test case when it comes to the fetishization of books as physical objects. Although many people would prefer to read a digital version of Home, it’s a good bet Google’s most ardent technophiles didn’t ask Morrison to sign their tablets instead of their paperbacks.

Signatures possess an idiosyncratic significance that does not translate well into bits and bytes. Even human interaction seems easier to digitize, a strange paradox vividly illustrated by Margaret Atwood’s 2006 invention of the LongPen. The LongPen combines standard video-chat functionality with a robotic signing station, purchasable, in theory, by any local bookstore. After meeting an author online, fans place their books in the station. Then, like a remote surgery system, the robot’s pen-wielding “hand” is guided in real time by its absent operator, faithfully reproducing virtual pen strokes in ink on a real page.

Atwood explains: “You don’t have to be in the same room as someone to have a meaningful exchange. As I was whizzing around the United States on yet another demented book tour […] I thought, ‘There must be a better way of doing this.’” She has now teamed up with Fanado, a company that distinguishes itself from other online signing services like Authorgraph.com and Autography.com in part by offering virtual fans a personalized “wet-ink” signature. But the LongPen’s supposed advantage raises some interesting questions. If, as Atwood claims, you don’t have to be in the same room with someone to have a meaningful exchange, then why do you need ink for a meaningful signature? And if ink really is required, are there other requirements that the LongPen fails to meet?

II.

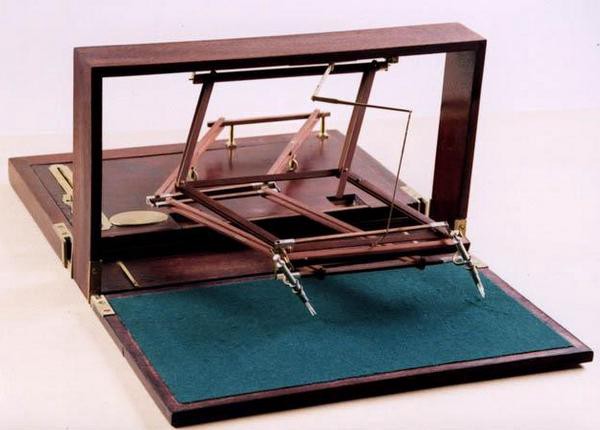

The ancestry of disembodied writing devices can be traced back to the polygraph, a primitive copying machine patented in 1803 and made famous by Thomas Jefferson, who helped improve the design and had one installed for personal use at Monticello. Mounted on a flat platform, the polygraph links a master pen to two slave pens using a set of hinged wooden rods attached to a bridge or “gallows frame.” An enthusiastic archivist of his own work, Jefferson prized the polygraph for its ability to copy letters as he wrote them, allowing him to send one letter and keep two others for his records.

The polygraph was an extraordinary feat of engineering. According to the Library of Congress, “it is nearly impossible to determine which copy of the page was made by the pen held by Jefferson.” Nevertheless, it’s hard not to feel like the “original” letters are somehow enchanted by their mode of production. This intangible difference is reflected in the rhetoric of auctioneers, who trumpet pages that come from the master pen, as well as in Jefferson’s habit of honoring correspondents with the original letters and archiving the polygraphed copies. In a blow to the LongPen, it appears that those who fetishize handwritten documents prefer them written by traditional hands.

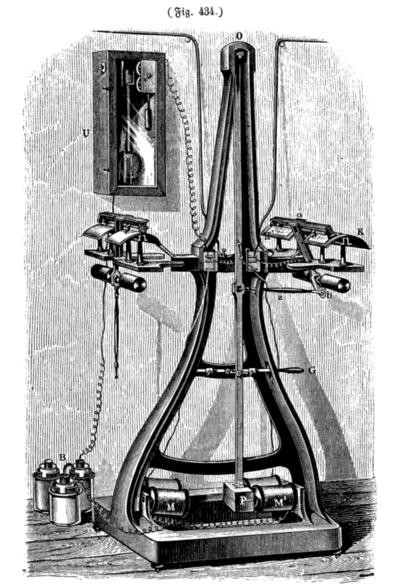

Sadly, Jefferson never lived to see the LongPen’s true functional ancestor, the first machine specifically employed for long-distance signing. Ingeniously combining two of Jefferson’s favorite inventions, the pantelegraph was developed by Italian abbot and physicist Giovanni Caselli in the mid 19th century. Fascinated by the telegraph’s potential, Caselli began work on a device that could transmit facsimiles of letters and images. His efforts eventually attracted the attention of Napoleon III, who financed the project and granted Caselli access to the French telegraph system to conduct experiments. In 1860, the pantelegraph successfully transmitted an image between Paris and Amiens, a distance of 87 miles. The image chosen for the demonstration? A signature, that of composer Gioacchino Rossini. (The pantelegraph’s mechanics are incredibly complicated; think giant fax machine with a pendulum that requires you to write on special non-conducting paper before sending.)

Standard telegraph proved more efficient than the cumbersome pantelegraph for information transfer, and Caselli’s invention was used almost exclusively for verification in long-distance banking. Only pantelegraphed documents could provide the legal authority necessary for financial transactions, transmitting messages “immediately from the hand of the writer” and “conveying a facsimile of every word and syllable […] bearing the full authenticity of the hand and signature, according to John Timbs, in The Yearbook of Facts in Science in Art of 1862.

Notwithstanding the widespread adoption of the pantelegraph and its successors, the telautograph and the fax machine, people remain dubious about the ability of machines to (re)produce significant signatures. Take the recent controversy surrounding Obama’s use of the autopen, another popular remote signing device. Autopens are highly customizable autonomous signing machines, capable of storing a variety of signatures for use on everything from traditional documents to sports memorabilia. They are routinely employed by presidents: Truman signed his checks by autopen, and there is an entire book written about JFK and his autopen called The Robot that Helped to Make a President.

But when Obama signed the Patriot Act from France with his autopen, a group of 21 House GOP members protested the Constitutionality of the signature, citing Article 1, Section 7, Clause 2: “Every Bill which shall have passed the House of Representatives and the Senate, shall, before it become a Law, be presented to the President of the United States; if he approve he shall sign it…” Obama is not the autopen, argued the lawmakers, ergo he exceeded his Constitutional authority by having a “surrogate” sign the bill.

Fortunately, in 2005 the Justice Department’s Office of Legal Counsel foresaw this problem and drafted an opinion for the Bush White House that justified Obama’s action. The opinion cites early common-law cases that locate the legal significance of a signature exclusively in the consent of the signatory: “if one of the officers of the forest put one seal to the Rolls by assent of all the Verderers, Regarders, and other Officers, it is as good as if every one had put his several seal….”

This seems like a reasonable position to take on a signature’s legal significance. But authors’ signatures have a different kind of significance, one that isn’t located in mere consent. That’s why Donald Rumsfeld couldn’t appeal to his legal counsel when it came out in 2005 that he’d been using the autopen to sign condolence letters for families of soldiers killed in action. It’s no surprise that the families (and the media) found the autopen signatures crucially lacking. A traditional signature requires time and personal attention. It is a sign of sacrifice, an element unnecessary for producing legal objects but essential for crafting sacred ones. Rumsfeld’s signatures may have been authorized, but they were utterly insignificant. (The same goes for Gregg Allman’s autopenned signatures on his memoir.)

The criterion of sacrifice might explain why LongPen and autopen signatures would be less significant than in-person signatures. Both machines, after all, are testaments to the signatory’s unwillingness to sacrifice time and effort. But according to the same logic, Toni Morrison’s virtual signatures should be no less significant than the paperback ones. She spent time producing them, in addition to interacting extensively with their recipients, a courtesy that probably wasn’t extended to the employees at Google’s New York office. So why the preference for pen on paper?

Resale value can’t account for it — signed copies of Morrison’s books can be had for a measly thirty bucks. Nor is scarcity an answer — there are far fewer of Morrison’s virtual signatures than her physical ones. As for the notion that digital signatures can’t be authenticated, well, the problem of authenticity is universal, affecting ink signatures and digital ones alike. It isn’t hard to imagine technology that could “tag” Morrison’s electronic signature, much as an ink signature is tagged by certain identifying characteristics. Digital forgery is a possibility, but that doesn’t explain why an “authentic” digital signature should be worth less. The fear that digital media are more perishable than paper was thoroughly discredited by David Bell in the New Republic, who points out that librarians are furiously digitizing physical media in the name of preservation. As any collector knows, paper books can fade, decay, suffer water damage, burn up, become lost or forgotten.

The mystery remains unresolved: for reasons independent of authorial sacrifice, the market, scarcity, authenticity, or perishability, physical signatures written by hand are more significant than their digital analogues.

III.

In “Unready to Wear,” Kurt Vonnegut imagines a Kurzweilian future in which humans are “amphibious” — capable of becoming disembodied at will. Amphibiousness is a tremendous advantage: no disease, no injuries, no politics, no toilets, no “old-style reproduction,” near immortality. Amphibious Pioneers can “meet on the head of a pin,” and they are “true to themselves, no trouble to anyone, and not afraid of anything.” The friendly first-person narrator assures us that any perceived drawbacks to disembodiment aren’t real, “just old-fashioned thinking by people who can’t stop worrying about things they used to worry about before they turned amphibious.”

The only job left for amphibians involves maintaining storage centers, where spare bodies are kept. Occasionally some people get nostalgic for embodiment, and the bodies are there to accommodate them. The centers provide a specialized service, tailored to the aged; as Vonnegut’s narrator puts it, “the youngsters… don’t even worry much about something happening to the storage centers, the way us oldsters do.”

Almost as an aside, we learn that the bodies serve one other purpose. Each year a group of amphibians occupies them for the Pioneer’s Day Parade, held in honor of Doctor Konigswasser, the discoverer of amphibiousness. At the head of the parade marches Konigswasser’s body, a miserable thing that the doctor himself refuses to reinhabit: “Ulcers, headaches, arthritis, fallen arches — a nose like a pruning hook, piggy little eyes, and a complexion like a used steamer trunk.”

Understandably, Konigswasser talks about humans like some ebook purists talk about books: “The mind is the only thing about human beings that’s worth anything. Why does it have to be tied to a bag of skin, blood, hair, meat, bones, and tubes? No wonder people can’t get anything done….” And yet, his emancipation of humanity from the physical is commemorated by a ritual that itself requires embodiment. It is as if the amphibians recognize that sacred practices belong to the physical world, that humans are only venerable in virtue of their dual nature as minds enfleshed, inconvenient though it may be.

In their own small way, authorial signatures also commemorate our nature, which informs our preference that they be physical and produced without a complicated apparatus. When I look at Norton Juster’s signature in my copy of The Phantom Tollbooth, when I touch the ink of his inscription, I am told a powerful story: Norton Juster wrote this, in the flesh. The story connects me to another human, to the bag of skin and bones that spoke so meaningfully to me when I was a little boy. This is the point of signatures, of relics and special places great and small: their attachment to narratives of physical encounters. Kurt Vonnegut wrote on this typewriter. Thomas Jefferson sat right where you are sitting. Thousands died in this room; see their scratches on the walls. Such stories do not translate well into bits and bytes. The ritual of book signing, like the Pioneers Day Parade, cannot be disembodied without loss.

Here is the most profound difference between ebooks and paper books. It’s not that paper books can be signed in ink — that’s a trivial advantage. It’s that they serve so well as relics. When we finish a life-changing book we return it to the shelf, or the virtual shelf — I do not deny that powerful reading experiences can occur with ebooks just as easily. But when I see the spine of a physical book on my bookshelf, when I pick up that same companion many years later, I am told a powerful story: You read this, in the flesh. That is the only story I hear. A once-read paper book has no other purpose than to be itself, and picking it up no other purpose than to remind me of our time together. When you pick up an ereader, on the other hand, more likely than not it is for the sake of doing, not commemorating. Fifty years from now, my paper relics will still be sitting on the shrine of my bookshelf, but the only Kindle anyone will keep around is the one signed, in metallic Sharpie, by Jonathan Franzen.

Alan Levinovitz is assistant professor of religion and philosophy at James Madison University. Read more at Top Philosopher Dot Com.

New York City, May 9, 2013

★★ Sequel time: another summer day looped backwards through the projector, with storms unbuilding to a clear and quiet finish. A tolerably damp morning turned into another downpour, and another downpour after that. When that part was done, everything was waterlogged, with the unwanted heat rising faster than the wanted brightness. Downtown, though, cooler air stirred, under inconclusive moments of clearing. By rush hour, once more, everything had all been resolved or forgotten. People wore their raincoats unfastened, to swing in the breeze.

Nobel Literature Laureates, In Order

by Jason Farago

109. Frédéric Mistral, 1904

108. Winston Churchill, 1953

107. Pearl S. Buck, 1938

105 (tie). Harry Martinson, 1974

105 (tie). Eyvind Johnson, 1974

104. William Golding, 1983

103. Jacinto Benavente, 1922

102. John Galsworthy, 1932

101. Odysseus Elytis, 1979

100. Camilo José Cela, 1989

99. Rudyard Kipling, 1907

98. Roger Martin du Gard, 1937

97. John Steinbeck, 1962

96. Hermann Hesse, 1946

95. Sinclair Lewis, 1930

94. Paul Heyse, 1910

93. Vicente Aleixandre, 1977

92. Rudolf Christoph Eucken, 1908

91. V.S. Naipaul, 2001

90. Pablo Neruda, 1971

89. Jaroslav Seifert, 1984

88. Ernest Hemingway, 1954

87. Ivan Bunin, 1933

86. Mario Vargas Llosa, 2010

85. Giosuè Carducci, 1906

84. Gabriela Mistral, 1945

83. Johannes Vilhelm Jensen, 1944

82. Pär Lagerkvist, 1951

81. Gabriel García Márquez, 1982

80. Władysław Reymont, 1924

79. Octavio Paz, 1990

78. Mo Yan, 2012

77. Miguel Ángel Asturias, 1967

76. Karl Adolph Gjellerup, 1917

75. Henryk Sienkiewicz, 1905

74. Erik Axel Karlfeldt, 1931

73. Orhan Pamuk, 2006

72. William Faulkner, 1949

71. Romain Rolland, 1915

70. Isaac Bashevis Singer, 1978

69. S.Y. Agnon, 1966

68. Saul Bellow, 1976

67. Grazia Deledda, 1926

66. Gao Xingjian, 2000

65. Tomas Tranströmer, 2011

64. Elias Canetti, 1981

63. Sigrid Undset, 1928

62. Nelly Sachs, 1966

61. Carl Spitteler, 1919

60. Henrik Pontoppidan, 1917

59. Naguib Mahfouz, 1988

58. Nadine Gordimer, 1991

57. Eugenio Montale, 1975

56. Gerhart Hauptmann, 1912

55. Wisława Szymborska, 1996

54. Frans Eemil Sillanpää, 1939

53. Doris Lessing, 2007

52. José Echegaray, 1904

51. T.S. Eliot, 1948

50. Jean-Marie Gustave Le Clézio, 2008

49. Kenzaburo Oe, 1994

48. Giorgos Seferis, 1963

47. Wole Soyinka, 1986

46. Selma Lagerlöf, 1909

45. Ivo Andrić, 1961

44. Verner von Heidenstam, 1916

43. Juan Ramón Jiménez, 1956

42. Seamus Heaney, 1995

41. Mikhail Sholokhov, 1965

40. Salvatore Quasimodo, 1959

39. Bjørnstjerne Bjørnson, 1903

38. Jean-Paul Sartre, 1964 (refused)

37. Imre Kertész, 2002

36. Albert Camus, 1957

35. Günter Grass, 1999

34. Joseph Brodsky, 1987

33. Claude Simon, 1985

32. Heinrich Böll, 1972

31. Toni Morrison, 1993

30. Patrick White, 1973

29. José Saramago, 1998

28. Sully Prudhomme, 1901

27. Harold Pinter, 2005

26. François Mauriac, 1952

25. Derek Walcott, 1992

24. George Bernard Shaw, 1925

23. Halldór Laxness, 1955

22. Herta Müller, 2009

21. Count Maurice (Mooris) Polidore Marie Bernhard Maeterlinck, 1911

20. W.B. Yeats, 1923

19. Elfriede Jelinek, 2004

18. Yasunari Kawabata, 1968

17. Dario Fo, 1997

16. Anatole France, 1921

15. Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn, 1970

14. Saint-John Perse, 1960

13. Boris Pasternak, 1958 (forced to decline)

12. Knut Hamsun, 1920

11. Luigi Pirandello, 1934

10. Czesław Miłosz, 1980

9. Rabindranath Tagore, 1913

8. Henri Bergson, 1927

7. Eugene O’Neill, 1936

6. Theodor Mommsen, 1902

5. J.M. Coetzee, 2003

4. Bertrand Russell, 1950

3. Thomas Mann, 1929

2. André Gide, 1947

1. Samuel Beckett, 1969

Jason Farago rants and raves for the Guardian and other publications. He’s on Twitter. Notting Hill portrait photographed by “outwithmycamera.”