Faun Fables Really Is The Best Band Ever

Dave Bry (at noon on Leonard Lopate and tonight at the Park Slope Community Bookstore), Faun Fables at the Knitting Factory, Har Mar Superstar at Le Poisson Rouge, plus James Salter and more! Tonight, so amazing.

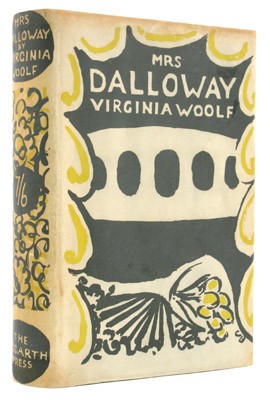

"Mrs. Dalloway" At 88

by Anne Fernald

Virginia Woolf’s Mrs. Dalloway was published on this day in 1925. Set on a single day in London, in June of 1923, it tells the parallel stories of Clarissa Dalloway, who is throwing a party, and Septimus Warren Smith, a shell-shocked World War One veteran. A perfect high modernist work, here are some of the reasons why the book still matters.

Woolf makes us care about a fancy middle-aged lady throwing a party.

From the opening line of the book — “Mrs. Dalloway said she would buy the flowers herself.” — we know we are with a married woman who is rich enough to have people around her to do errands for her. If most of us need flowers, there is no one to tell; Mrs. Dalloway has maids. Some people confuse Virginia Woolf with Mrs. Dalloway, but it’s more accurate to say that Mrs. Dalloway represents the world that Woolf’s mother (who died when Woolf was just thirteen) imagined for her, a conservative, social world that Woolf left behind for art, feminism, and Bloomsbury. In asking us to empathize with Clarissa even while she shows us that Clarissa is a shallow, silly woman who has little to show for her fifty-two years, Woolf returns to all she rejected and finds the possibility that even the people she most rebelled against have souls, have regrets, and have ways of living with courage in spite of it all.

The characters have great names that have interesting histories.

Clarissa shares her name with both the heroine of Samuel Richardson’s 1747–8 novel and the character who, in Alexander Pope’s The Rape of the Lock (1711–14) provides the scissors to cut off (thus, “rape”) the lock of Belinda’s hair. In early 1925, just after finishing Mrs. Dalloway, Woolf wrote an essay on The Rape of the Lock, in which she compared Pope to Chekhov. Thus, Clarissa Dalloway, whom we see with her sewing scissors and who seems virginal in spite of marriage and motherhood, is associated with both the accessory to a satiric “rape” and the most famous rape victim in the history of the novel. Septimus’s name seems weirder to us now than it once did. In large Victorian families, the parents of seventh-born children occasionally threw up their hands and began numbering their offspring. Woolf’s brother’s nanny in the early 1920’s was a seventh-born child, Daisy Selwood, nicknamed Septima. And, in the large blended family of Leslie Stephen and Julia Duckworth Stephen, Woolf herself was the seventh-born child.

It’s a great example of a novel set on a single day.

Woolf was famously unable to appreciate Joyce’s Ulysses, calling it an “underbred” book. However, three years later, in Mrs. Dalloway she tried the same experiment. The verbal pyrotechnics of Woolf’s novel are different (see below), but the tolling of Big Ben’s bells marks the hours throughout the novel and, like Joyce, Woolf uses modernist techniques to offer us glimpses of the thoughts and memories of characters who only exist for a single day. The Hours was an early title for Mrs. Dalloway and the finished novel does not have chapters, but section breaks. Those section breaks have been plagued with errors since the first printing, where several section breaks fell at the bottom of a page and thus became invisible. However, if you follow Woolf’s instructions, the novel has exactly twelve sections, hardly a random number for a daylong novel. The longest section begins at noon.

Woolf deploys allusions to Shakespeare like a master.

There are a lot of allusions in Woolf, and a lot of them are easy to miss. When you get them, however, they deepen the story. One of the main ways that we learn to see Clarissa as a kind and sympathetic person is through a literary coincidence: although she never meets Septimus, both characters take comfort in the same song from Shakespeare’s somewhat obscure late romance, Cymbeline: “Fear no more the heat of the sun / Nor the furious winter’s rages.” This dirge, sung over the body of an apparently dead boy (but really a living girl) connects the living woman to the soon-dead man. Other allusions to Shakespeare are similarly calculated to exercise your inner English major. Woolf plays with gender roles again when Clarissa remembers her love for Sally Seton when they were younger by quoting Othello, upon first reuniting with Desdemona: “if it were now to die ‘twere now to be most happy.” We can guess that Septimus’ volunteering for war will be ill fated when he associates his love for his teacher, Miss Isabel Pole with Antony and Cleopatra, and not, say Twelfth Night. And finally, Lady Bruton, who should have been a general, gets to quote Richard II while Woolf simultaneously takes pleasure in and makes fun of her patriotism: “this isle of men, this dear, dear land, was in her blood (without reading Shakespeare).”

It continues to inspire other works of art.

Toni Morrison wrote her M.A. thesis on Woolf and Faulkner and you can see a direct link between Septimus and Shadrack, the WWI veteran and founder of National Suicide day in Sula. Gregoire Bouillier’s memoir The Mystery Guest (appropriately tongue-in-cheek trailer here), set around one of performance artist Sophie Calle’s birthday parties, has the Bouillier and Calle’s mutual admiration for Mrs. Dalloway as a central conceit. Michael Cunningham’s The Hours and the movie of the same name are really lovely tributes to the book. The Laura Brown section, about a discontented housewife reading Mrs. Dalloway, Doris Lessing-style, alone in a hotel room, is particularly smart and made so much better when linked to the novel. And, although Ian McEwan would rather have you think of him with Bellow and Mailer, his Saturday, about a wealthy surgeon whose spends the day getting ready for a party under the shadow of 9/11, is, of course, a retelling of Mrs. Dalloway.

It’s full of London history.

Richard Dalloway tsk-tsks the terrible traffic at Piccadilly Circus, and in doing so, he records an ongoing London problem of the time. In fact, buses, hand- and horse-drawn carts, carriages, automobiles and pedestrians all competed to cross streets at a time when traffic signals still had to be changed manually by a traffic officer. Traffic in Piccadilly especially was the subject of many newspaper articles and resulted in multiple government committees, studies and reports during the early 1920’s — committees of just the kind that Richard, as a Member of Parliament might sit on. This 1927 film clip offers a sense of the traffic.

http://player.vimeo.com/video/7638752?title=0&byline=0&portrait=0&color=c9ff23

Early in the novel, the driver of the mysterious car on Bond Street waves an ivory disk and escapes another traffic jam. Such passes are now largely forgotten, but were once a common perk for railway directors and other people of privilege. You can see one such ivory disk, a coach pass, here. When Clarissa shops at Hatchard’s, she is shopping at Lord Byron’s bookshop, a shop that has been at the same London address, catering to aristocratic poets and fancy ladies buying books for their friends in hospital since 1797. But when she thinks of having been to parties at Devonshire House, she is marking the passage of time: Devonshire House was demolished in 1924, after the novel’s 1923 setting but before its 1925 publication date. Devonshire House is preserved in Clarissa’s memory, and her memory of it is another clue to her own coming obsolescence.

Even the random details are not random.

Joseph Breitkopf, who once taught Clarissa German but really prefers to sing lieder, shares his surname with the preeminent German music publisher. When Hugh consults a clock outside the fictional department store, Rigby & Lowndes, not only are R-I-G-B-Y (5) and L-O-W-N-D-E-S (7) precisely twelve characters, (one for each hour on the clock face), but they were the surnames of English suffragettes. In 1913, Edith Rigby threw a black pudding at a Labour MP in Manchester and set a bomb (which did not explode) under the Liverpool Cotton Exchange. Mary Lowndes was a stained glass artist and a regular contributor to the feminist magazine The Englishwoman.

We still need to remember to take care of veterans and we still don’t do enough.

When Clarissa hears of Septimus’ suicide, she retreats from her party. In a quiet room, she thinks about him with great sympathy and, in his death, finds courage to rejoin her life. Many people find that moment, when she stands alone, looking across the way at the old woman opposite, one of the most beautiful moments in the novel. The novel depends on our conviction that, more than any of the other characters, Clarissa understands Septimus’ decision to end his life. And Woolf shows us to link that decision, arising out of despair, with the lack of sympathy Septimus faces, especially from his doctors. In the 1920’s, many people still looked on war trauma as cowardice and there was some support for treating suffering veterans as deserters. I don’t think it’s entirely satiric when the men harrumph, on the news of Septimus’ death, that “there must be some provision in the Bill.” In the end, Woolf values Clarissa’s sympathy more, but I think Woolf shows us the decency in Richard’s actions, too. Septimus’ death is an offering and a statement, an act of desperation in the face of continued appalling medical care — in this moment, the prospect of being sent away from London and his wife. Woolf, who suffered from depression off and on throughout her life, knew too well what bad doctors could be. In the 1920’s, the care Woolf endured — isolation, forced inactivity, over-feeding — was identical to what most shell-shock victims would have endured. Only a very, very few physicians, such as W. H. R. Rivers, had begun a talking cure as treatment for war trauma. For Woolf, suicide was a decision and could be a rational one. The only page that Woolf substantially changed in revising the page proofs is the page on which Septimus commits suicide. To that page, she added his thinking about how to do it: taking Mrs. Filmer’s bread knife into consideration — “mustn’t spoil that,” he thinks; wondering about gas and razors; embarrassed to have to throw himself out the heavy Bloomsbury lodging house window.

Anne Fernald is the editor of Mrs. Dalloway for Cambridge University Press (forthcoming). She blogs at Fernham and teaches at Fordham’s Lincoln Center campus.

New York City, May 13, 2013

★★★★ Waves and the shadows of clouds made the river look unsettled in its bed. It was cool enough out to be a genuine surprise or anomaly, corduroy conditions. Wind audibly sighed through the thickly leafed treetops; green maple wings lay on the sidewalk. Downtown, in the afternoon distance, solid buildings stood with solid-looking clouds behind them. Striking but harmless grays were framed by whites and blue. The living room was golden, and the light flooded the face of the bedroom till the black numbers and hands on the clock were invisible white.

The 2 Simple Things You Need To Know To Chessbox

“If you know how to play chess and you know how to box, you know how to chessbox.”

Kendrick Lamar, "B*tch Don't Kill My Vibe"; Rahsaan Roland Kirk, "I Say A Little Prayer"

There’s been plenty written about how great Compton rapper Kendrick Lamar’s album, good kid, m.A.A.d. city is. So much that I’m left with feeling like I have little of value to add to any conversation about it. But the video for “Bitch Don’t Kill My Vibe,” came out today and it inspired in me a thought(!) First of all, it’s really good. Watch it. Secondly, jumping back and forth in tone as it does, it makes a nice point about how complex everything is — death, religion, fashion, mourning, partying, solitude, unity, nature, all this stuff. All sorts of paradox. Which starts to come as close to truth, I think, as our little human brains can muster. Anyway, sorry for getting a little carried away there. That’s three cups of coffee talking. And probably largely nonsense. But it made me think a lot of an old favorite album of mine that I haven’t listened to in a really long time. Rahsaan Roland Kirk’s Blacknuss.

Rahsaan Roland Kirk was a jazz saxophonist famous in the ’60s and ’70s for being able to play multiple wind instruments at the same time — like, really at the same time, like with two horns stuck in his mouth at once. It’s something to see. And his music was often chaotic and “out” in the free jazz meaning of the term. But then, Blacknuss, released in 1971, is a fusion album (jazz fusion: that beloved genre that has aged so well in the minds of music critics!) It’s Kirk leading his band through a bunch of the pop hits of the time. Bill Withers’ “Ain’t No Sunshine,” Marvin Gaye’s “What’s Going On,” The Temptations’ “My Girl,” etc. I imagine some people thought it was pretty cheesy when it came out. I bet others didn’t listen to it because it sounded too weird. (Kirk sings the words to “Ain’t No Sunshine” through his horn while he’s playing.) So like, it’ll probably appeal to some people, and then piss other people off for the same reasons. And for lots of different reasons. But I like the paradox: how for a great artist, compromising — finding a way to fit in a little something for everyone — can be the most uncompromising stance at all.

Here’s Rahsaan doing Aretha Franklin’s “I Say a Little Prayer” in 1969. Confused and wild and all over the place and gorgeous.

Commenter Really Into Alcohol

“Reading articles like this I often wonder if I’m alone in drinking because I … like the taste of alcohol. I don’t find getting drunk all that pleasant or a good social prop (quite the opposite, I hate making a fool of myself because drink has dulled my social reactions). Because of its depressant effect I find I drink less when I’m feeling down than when I’m feeling good. I drink because I don’t know of anything nicer than a rich red wine or port on a winter’s evening, or a crisp, mineral white wine on a summer’s day. I love the complexity and sharpness of a good IPA and the satisfying richness of a well poured stout. Any mix of fruit juices tastes vastly better with the body and kick of a clean-tasting vodka or tequila. Alcohol, like good food or fresh air or the smell of flowers, is just one of the things that makes a good life that bit better.”

Photo by wavebreakmedia, via Shutterstock

43 Things That Will Make You Feel Old

43. Aching feet

42. Failing eyesight

41. Everything taking at least ten minutes longer than you planned

40. Frequent late-night urination

39. Cracking sound each time you stand up

38. Ear hair

37. Nose hair

36. Head hair (in sink/shower)

35. “Sorry, I couldn’t hear you.”

34. “Just resting my eyes.”

33. Unreliable memory

33. Ultra-reliable memory (i.e. increasingly frequent and vivid memories of things you’ve long since forgotten rushing in at inappropriate times)

32. “10th Anniversary Edition”

31. “Deluxe 20th Anniversary Edition”

30. “Special 25th Anniversary Commemorative Edition”

29. Punk kids getting nostalgic about the Nickelodeon cartoons of a few years back

28. Current Nickelodeon cartoons

27. “Like” and “share”

26. Having to learn what “twerking” is

25. Having to think about whether or not you should eat that

24. Regretting your decision to have eaten that

23. Knowing that the rest of your life will be spent watching other people eat that with abandon while you have something considerably less flavorful

22. Not caring enough to get upset about someone else’s success

21. Feeling sympathy when unfortunate events happen to people you spent a long time disliking

20. “Has that spot always been there?”

19. Coming to realize that if something hurts it is probably just going to hurt from now on

18. Coming to realize that pretty much everything hurts

17. “Can you turn that down?”

16. Crossing the street when you see a large group of boisterous young people heading towards you

15. Being invisible to the large group of boisterous young people heading towards you

14. Classifying large segments of the population as “young people”

13. Inability to be boisterous

12. Thinking “it’s kind of late” after 9 PM

11. Waiting until 10 PM so you can go to bed without feeling extra lame

10. Waking up at 5 AM and knowing you can either lie there for another hour or get up and start your day, because the one goddamn thing that’s NOT going to happen is you falling back asleep

9. The death of older relatives

8. The death of your friends’ parents

7. The death of your own parents

6. The death of your friends

5. The death of the hopes, dreams and ambitions you still somehow thought possible even after it made any sense to

4. The strange acceptance that descends after you’ve had enough time to understand that the death of the hopes, dreams and ambitions you still somehow thought possible even after it made any sense to is for real

3. The understanding that you are not so far off from your own demise, at which point everything you’ve experienced will be wiped away as your complete insignificance becomes one with the end of your consciousness

2. The strange acceptance of the futility of your own existence and its imminent cessation

1. “Decaf”

Alex Balk can’t imagine how much older he’s going to feel in ten years. If he makes it.

Gay People Just As Good At Playing Pretend As Straight People

“Clemson University researchers studied an issue raised in a recent news column that suggested an ‘out’ actor cannot convincingly play a heterosexual because knowing someone is gay will bias perceptions of his or her performance. Researchers discovered that although knowing an actor is gay significantly affected ratings of his masculinity, there was no significant effect on ratings of his acting performance.”

How To Write About Tragedy And/Or Lindsay Lohan: Advice From Stephen Rodrick

by Michelle Dean

The Rodrick Family in 1972

Stephen Rodrick, a contributing writer to the New York Times Magazine, of late best known for the single best story on Lindsay Lohan ever, has a new book out today called The Magical Stranger: A Son’s Journey Into His Father’s Life. His father, Commander Peter Rodrick, died in 1979 when his Prowler crashed into the ocean. The book traces the aftermath of his father’s death for his young family, and its ripple effects in Rodrick’s adult life — but is also a book documenting military life today. It’s also really good, particularly in the way it calibrates the telling of such an openly emotional story. It’s not easy to write something like this without coming off as maudlin, but Rodrick’s natural talent for self-deprecation keeps everything elegant, so that the book devastates you in a way only a really fine implement can. We talked about the book by email.

The book is structured in such a way that it flips back and forth between your story and that of another pilot, James “Tupper” Ware. (Heh.) Of course your stories eventually become entwined, but without giving away the game, can you comment on why you chose to structure it that way?

I’d been kicking the idea of writing a book about my father who was killed in a plane crash off The USS Kitty Hawk when I was thirteen. He was a ghost in my life, even when he was alive, gone 200 days of the year. Then I did a magazine story on Navy pilots about a decade ago that some people liked. I remember having a drink with an agent at Brooklyn Social and he was talking about how he could sell it and we could have it come out around Father’s Day. And there was something weird about it, the whole commodification of tragedy.

So I backed away and decided the only way I could do the book was if there was a component of reporting to it that involved me getting out of my head and writing about my family’s loss in a larger context, namely what it is like to serve in an era of two wars and endless deployments. When I was trying to sell the book, an editor I like shrugged his shoulders and said ‘I’m not sure how you’re going to link these threads. My response was ‘Yeah, that a real good question. I have no idea!” Shockingly, he did not buy the book.

The Magical Stranger

• Amazon

• Barnes & Noble

• Indiebound

• McNally Jackson

• Readings

But the fact that Tupper held my Dad’s last job, skipper of VAQ-135, a squadron based on Whidbey Island in Washington state, gave the memoir and the current stuff a certain symmetry. Going back and forth seemed natural, I was hoping to show a family blown apart by military service — my own — nd a family — Tupper’s — trying NOT to be blown apart by military service in real time.

Oh and in the end, the book is coming out a few weeks before Father’s Day. And I want people to buy it and read it. Agent guy was right. I was wrong. This happens to me, on average, seventeen times a day.

Has Tupper read the book?

Tupper hasn’t read it. He said early in the process he didn’t want to read it before it came out. That was very cool of him. I did make an extra trip to Dubai and we spent 3–4 days holed up there — me with bronchitis so loud I was sleeping in a walk-in closet to muffle the gruesome noise — and we went over the facts of his story a last time. We literally did not leave the hotel grounds for the entire time of stay. That’s really the only way to do Dubai. I’ll be up on Whidbey Island on Thursday and Friday and we’ll see if the Navy folks love it or hate it or somewhere in between. I’m sure there will stuff that the guys will be like ‘I wish you hadn’t put that in,’ but we’ll see.

“Tupper” at work

It’s interesting that you felt reluctant to “commodify” your “tragedy,” as you put it, since we live in this age of ascendance of the personal essay. I think you handled it pretty well, actually, being honest about the emotional impact of your father’s death while not making this book feel confessional even in its most directly personal moments. (It’s funny but I could see in it the same light-but-honest touch you had on that Lindsay Lohan profile I loved, though it was someone else’s tragedy there.) Could you talk more about how you negotiated that boundary with, you know, yourself? Did you just have to shut off the yelly in-writers-head voice that repeats, “This is EXPLOITATION” (not that it always is, it’s a self-doubt thing) over and over again?

Well, in the end, to fall back on a tired cliche, it turned out to be a story I needed to write. If I had a dollar for everyone who told me “you have to write this,” I’d have exactly 43 dollars. I needed to get it out whether anyone read it or not.

But the idea of not making it tragedy porn stuck with me through the whole process. I consciously wanted the tone to be a bit minimalist with a light touch and heavy on the quiet heroism and utter absurdity of military life. I really love Hanif Kureishi and Evelyn Waugh and their novels have death and war and revolution, but they’re not overwrought or filled with 87-word sentences or page-long paragraphs. They’re more: this is what life is about; a mixture of glory, death, and kicks in the crotch. And they’re fucking funny. Their writing is filled with absurd comedy amongst lives falling apart — the end of Waugh’s A Handful of Dust where the fallen aristocrat Tony Last takes a misguided South American expedition and finds himself reading Dickens to a man gone native, perhaps for the rest of his lifetime, is my favorite chapter of fiction — and that’s pretty close to my worldview.

I’m not interested in creating a fable or myth about my father or Lindsay Lohan. The idea is to humanize the icon whether it’s my dad or a starlet. Show people as they really are and let the reader draw their own conclusions. I’m not saying it was completely conscious as I was writing the book, but I wanted to show my family and Hunter Ware’s family as we really are, whether that meant dysfunctional, heroic, broken, or obsessed with pulling off elaborate pranks involving statues of little German boys in lederhosen. (Buy the book). The life of a navy pilot is more Catch-22 than Catch-22 and I wanted to capture that. I sometimes get called a cynic or a shitliver, but you lose your father under these circumstances, you’re going to have a slightly dark view of the world. Still, I spend a large part of my day chuckling while watching Love Actually.

I am curious to know, given that I know you as sort of funny and sardonic, what precisely appeals to you about Love Actually (funny and sardonic not being words I am moved to apply to that film).

Oh man, will the New York snobbery about Love Actually never cease? I’m tempted to rip off the mic and leave you with dead air. But I was raised better.

It’s a great corny movie with tons of excellent actors vamping; The Hobbit Guy, Kenneth Branagh’s ex-wife, the man from Taken, Stacey from “Gavin and Stacey,” Betty Draper, and, I think, River Phoenix. Do I need to go on?

Richard Curtis makes well-made, humane middlebrow stuff that I enjoy like a nice bowl of Frosted Flakes after a hard day at the office. (Sort of like a good general interest magazine article). Curtis wrote The Tall Guy, one of the most underrated British comedies of my lifetime and also The Girl In The Café with Kelly MacDonald and Bill Nighy as a completely preposterous couple trying to find their way during a G-8 summit in Reykjavik, Iceland. Kelly MacDonald. Sigh. I was so grateful Kelly didn’t get murdered in No Country for Old Men. Weren’t you? Should I go on? Wait, where did you go? There’s a certain British-based romantic comedy — About A Boy, Truly. Madly Deeply — that melts this American’s cold, cold heart.

I love The Girl in the Café too. And I agree, there’s something super-romantic for me about the sort of restrained-Brit approach to romance. But life is not like the movies, etc.

One big moment you do get into, in the book, is how your first marriage broke up. And to an extent some of this journey, though you’re more oblique about it, is motivated by a new romance. I liked how you were not, you know, hokey about any of that stuff though. I wonder if you might be really imitating the quietness of the Brit romcom, at least a bit?

Maybe! I do think the British do a generally better job at conveying “we are mostly well-meaning knuckleheads living life out in our own idiotic and quixotic way.” The thing that makes a movie like Withnail & I funny and touching and sad is that it is real. There are really people out there who live like that. Many of them are my friends. But America doesn’t do that kind of comedy as well. There’s always a redemption at the end; the couple stays together or the guy gets the beautiful girl. Withnail & I ends with one guy getting cast in the lead of a play and another, Richard E. Grant, is shouting drunken Shakespeare at animals in the zoo during a downpour. That’s how life really is.

Breakups of marriage are similar; they’re usually brutish and excruciating and full of self-degradation. And, in retrospect, that kind of meltdown is so full of laughs, I couldn’t help but mine them a bit.

Yeah, but it is still be hard to write about. All this family stuff is hard to write about because, well, you know, people sometimes don’t like what you write about them. Have your mom/sisters read the book yet?

My sisters were like Tupper, they were both ‘We’ll read it when it comes out like everyone else.’

Now my mom, she got to read it in galley.

Funny story. Well, not funny ha-ha. I flew out to Michigan in a futile pursuit of an interview with Charlie LeDuff and gave her a copy. I was staying with my sister about 15 miles away. After a few days, Mom called and said she’d read it and why didn’t I come over lunch?

I drove over, heart pounding, and she told me “I really like it.” I was so relieved. We watched the Lions game and I went back to my sister’s on some kind of high of there not being a lot of drama.

I spent the next day while my sister was at work and her kids were in school blasting Prefab Sprout on their stereo and dancing around in my boxers in relief. Alas, my sister came home that afternoon and said, “You gotta talk to Mom again, she complaining about the book all over town.” (Which means probably three people.)

Uh-oh. I got a little nauseous and climbed back in my car. In my jean pocket was a Xanax that either I was going to take or I was going to make my mother take. I got there, took a breath, and went in. My mom said, “I don’t want to rain on your parade, I know you’ve worked so hard on this but, I kinda come off as a bitch. There’s no mention of me getting food on the table, keeping your clothes clean, and getting you to all your practices.”

And she was absolutely right. I’d forgotten all the little things that a mom does. What a jackass I’d become! I went back into the galleys and added maybe five or six sentences and they totally made the book better. The Xanax ended up going through wash which was a tragedy in its own right.

The effect on families, though, I think you dramatize that so well. I’m a military kid too. So for me, one of the most interesting parts of the book is how you kept connecting your peripatetic habits as an adult with having grown up with that habit of moving around, to different schools and such. I thought you articulated the rootlessness of that so well. In your case it was complicated by the loss of your dad, but I wonder: do you agree with me that, in a way, this is a thing that is a sort of universal, for military families?

Well, it took me years to make that connection. You grow up as the chronically new kid, the one who doesn’t know anyone, doesn’t know what bus to get on, doesn’t know where the bathrooms are, etc. And what a shocker, that’s pretty much the definition of a magazine writer’s life. You’re dropped into established worlds and you have to master the language and culture quickly or you’re sunk.

I may have taken this to absurd levels — as an adult I’ve lived in Chicago, Washington D.C., Boston, Philadelphia, Brooklyn, and now Los Angeles — but there’s an itch that kicks in after a couple of years of living somewhere or working somewhere. It’s built into your DNA from birth when you’re a military kid — I detest the term military brat — and it’s hard to leave behind. I grew up in a house where moving stickers and boxes were as natural a part of our garage as the lawn mower and my Schwinn.

Now my little sister had a totally different life. She was two when my father died. I walked her to the bus stop when she started kindergarten with her best friend Sally and they went to school together for the next thirteen years. She lives 30 miles from where she grew up. In my first thirteen years, I went to eight schools in five different cities.

For me, it’s alternately a fantastic and self-destructive way to live. There’s a built-in confidence that you can make your way in the world, but there’s also that pit in your stomach because you know that you don’t really have a true home. It’s something I used to brag about, but not any more. From 2003 to 2009, I split my time between New York and LA, kept the same set of clothes in both places so I could travel back and forth with just my laptop, maybe deciding at 4 p.m. on a Wednesday that I would fly out the next morning. It definitely had its moments, but you’re always chasing something, never standing still long enough to cherish what you actually have right in front of you. The book, in some ways, is the 120 proof version of that life, I’d get permission to get on a carrier for a week and I’d have to get to Dubai or Bahrain in four days. It takes a toll on you both physically and psychologically. That’s why both the military and some aspects of journalism are a young person’s game. At some point, your body just says ‘enough.’ I’m not quite there, but you can see how this way of living takes years off the back end of your life.

But what was I going to do with the back end anyway? Just watch Love, Actually. Over and over again.

I always think that this is a sort of unaddressed sacrifice of military life, though, the rootlessness, which is funny because military people are obviously terribly patriotic people and are very clear about “where they’re from” in that sense. But the thing is, it’s very hard on little kids and on marriages, too. You write in the book of learning [slight spoiler] that your dad actually told your mom she just had to get used to his career or else, you know, give up on him and on the marriage. And as I read that I both agreed that it was a jerkish thing to say and yet somehow identified with the passion of it. Sometimes if you think you’re meant to do something — like fly a plane, or like writing — it is pretty easy to put everything else second. Women of your mom’s generation, and even of mine, I think, didn’t have the option of doing what was important to them and couldn’t see this, but I guess it goes to show that even men with comparatively large professional freedom couldn’t “have it all,” either. Do you agree?

I think you’re right. One of the themes of the book is men who have long-suffering and ultra-patient women supporting their dream so they can stay a kid and fly jets at the speed of sound off a carrier and hang out with their buddies in the bar at the Raffles Hotel in Singapore. Uh, when they’re not defending freedom.

On the surface, the men have it all, but they really don’t. Tupper took command — theoretically the high point of his life and something he had spent two decades working for — but it was breaking his heart. He was about to go to sea and miss almost an entire school year of his two girls. He knew he’d come home to two different people. And I think there was a lot of ‘My God, what have I put my family through and what was it all for?’ There’s a moment in the book where we’re riding a bus back to the USS Lincoln from a visit to the Bahrain naval base and the bus is full of the raucous laughter of sailors on leave and there’s more than a whiff of vomit in the air, something Ware once reveled in. And Tupper just turned to me and said ‘I can’t be around this any more.’

I do think some of that is translatable to writing or painting or any kind of work that is more than a job, a work that is your life. Am I going to regret when I’m old that I spent three Christmases on planes on the way to assignments? Maybe. I keep trying telling myself that life isn’t about acquiring the best anecdotes, it’s about having an actual life. And sometimes I almost believe it.