What Will You Be Thinking As You Die?

If am somehow conscious while it is happening, I think my first thought when I am about to die will be, “Jesus, finally.” But I’m pretty sure my second thought will be, “What an idiot,” no matter what the circumstances. Hopefully there won’t be time for a third thought.

The Best First Sentence Of A Novel This Year (So Far!)

“The summer following the winter that my mother took off into something called Women’s Land for what I could only guess would be all eternity, my father decided that there was no choice but for him to quit his despised job and take me and my brother to the beach for at least the entire summer and possibly longer.”

— How can you not want to read September Girls since it has one of the great first sentences of all time?

• Indiebound • Amazon • Powell’s • Barnes & Noble

Working at 30,000 Feet on Your Ultrabook™

“Before I had to be on a flight at least twice a week for work, I’d rather have stared quietly at the seatback in front of me for two hours than muster up the enthusiasm to get anything productive done on an airplane. Now that I’m racking up frequent flyer miles, it’s become a priority for me to treat the tray table as an extension of my office and it isn’t always easy. Here are a few tips to keep you on task, because its way more fun to enjoy happy hour at your destination than it is to finally finish that spreadsheet you’ve been putting off.”

What Side Of Your Brain Are You Giving Cancer To?

“A new study suggests that people with left-brain dominance tend to listen to their mobile phones with their right ear, and vice-versa.”

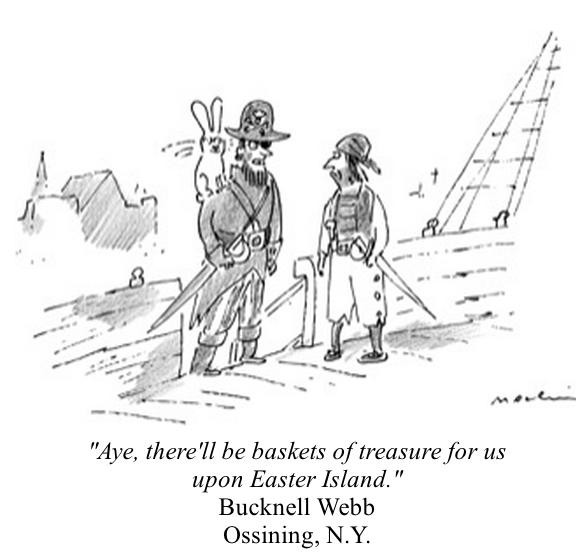

The Alien Mysteries of Easter Island

by Willy Staley

The caption above, selected from a pool of hundreds in the New Yorker’s caption contest #378, and then voted to the top of the pile by New Yorker readers, is reasonably witty on the surface, insofar as Cadbury Creme Egg commercials are witty. But like the best satire, this caption works on two very different levels. Masquerading as complete and utter pablum — literally fodder for children — it hints at a violent end to Western Civilization as we know it.

It might be hard to understand why this caption won the contest if you only look at its surface features. The losing captions of this contest’s three top choices — “I’m rebranding” and “He’s a temp” — at least address the presence of the other pirate, and incorporate him into the author’s temporal interpretations of the scene. In those instances, the pirate on the right, surprised by the bunny on his Captain’s shoulder — where cartoon tradition, if not pirate tradition, would call for a parrot — has clearly asked him, or at least indicated the presence of the question, why there is a bunny on his shoulder. Not only do the Captain’s responses incorporate a proper dose of New York-style ennui, and the ironic use of corporatespeak to evoke it, they have a sense of timing. In both the losing captions, something has happened before we entered.

But, then again: has it? Upon further inspection, little action has taken place, because the authors of the losing captions have merely made the second pirate into a “bridge” character for themselves — they are surprised at the bunny, therefore he is surprised at the bunny, and therefore all the Captain can do is offer explanations for it. By creating a universe wherein the Captain’s bunny is not actually surprising — or at least by muffling this impulse — the winning entrant, Bucknell Webb, has actually outdone the competition, though it required making a caption that is comparatively static.

The Easter Bunny joke is so obvious, it makes explanation a bit of a chore, but the questions it leaves unanswered reveal the same issue Webb has with establishing a timeline before this caption “happens”: Does the bunny speak, and so did the bunny tell the Captain to go to Easter Island? Does the Captain just really like Easter, and so the bunny is an outward affectation of this love? Certainly it’s amusing to infantilize a raider of the high seas by making him excited about getting a basket stuffed with paper grass, pastel candies and Peeps, but Webb’s caption offers no causal relationship between the Captain’s utterance and the bunny perched on his shoulder. (And I’m sure you’ve noticed this, but let’s just set aside the strangeness of the fact that Webb’s Captain addresses a subordinate with “Aye.”) But on the surface, it is only clever thanks to the associations already in our heads: that bunnies go with Easter, and so do gift baskets; that Easter Island is an island, and therefore plausibly a place a pirate might go pillage. But this soon breaks down when we consider the contrapositive: would a parrot-wearing pirate demand to go to Parrot Island, if such a place existed? And could his parrot demand it of him?

This is where Webb’s brilliant caption requires effort on the reader’s part. As little as his caption offers temporally on the front end, it hints at a much longer narrative afterward. Environmentalists know Easter Island, or Rapa Nui, as a harrowing, microcosmic parable for what awaits our unsustainable society: environmental collapse, followed by a return to the brutal Hobbesian existence from which we emerged tens of thousands of years ago.

The long-held story of the island goes like this: by the time Westerners first made contact with the Rapanui, for the people carry the same name as the island — and on Easter Day, hence the name — the culture was already in decline. Their population had been decimated, reduced to cannibalism. To the new arrivals, it seemed rather unlikely that such savages could be capable of constructing 887 massive stone faces, the moai, that line its shores. And, indeed, if you check the Ancient Aliens website — that show dedicated to the notion that non-white people are so totally incapable of creating anything lasting that alien visitors must actually be responsible for most of their accomplishments — we learn that it is highly unlikely that “human beings without sophisticated tools or knowledge of engineering craft [could] transport such incredible structures.” So: aliens?

But, despite what the History Channel considers to be an inborn deficiency, the Polynesian natives of Rapa Nui had actually figured out a way to move the moai: they cut down trees, and built roads, so they could roll the massive slabs of rock around the island. Eventually, the story goes, they cut down all their trees. And without them, they had no wood to make boats, so less fish, but also no fruit, and no tree-dwelling animals — and presumably little shade. Eventually, Rapanui society collapsed under the weight of its strange version of ancestor worship. Apparently, the moai were made for ancestors, based on the belief that the dead would provide for them. Eventually, the dead did indeed provide sustenance, though not in the way anyone had intended.

(But then came, as it always does, the anthropological reassessment. Rats, and their loves of trees, and then the European invaders, were what largely claimed the lives of the people and of the trees of the island. “It was genocide, not ecocide, that caused the demise of the Rapanui,” summarized anthropologist Terry Hunt.)

So our Captain, perhaps misled by his bunny, is foolhardy to think he will find bounty on the shores of Easter Island. He will find only rat-starved cannibals and massive stone faces he will likely assume to be the work of aliens. Then, in the logic of all cartoons, he will be boiled in a large cauldron with his comrades while the Rapanui wield comically large utensils, his fellow pirates cursing the Captain for listening to that traitorous bunny.

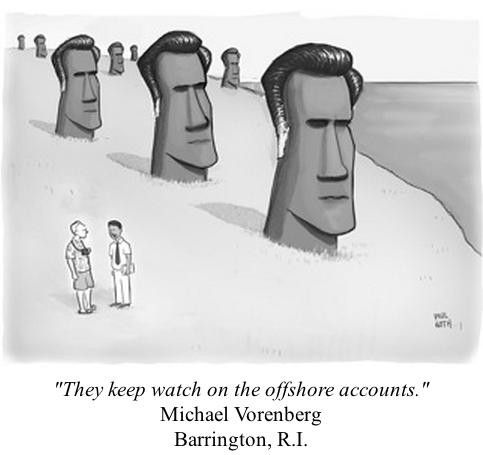

We hope that winning captionist Bucknell Webb read The New Yorker’s excellent coverage of Mitt Romney’s 2012 fool’s errand, and if that’s the case, then somewhere in his brain there likely exists an image of Romney’s face carved into the moai — it was Caption Contest #348, for September 10th, 2012.

The winning caption seems obvious. Romney, Webb has certainly not forgotten, was what we called a “corporate raider” in the 1980s: a private equity man. And aren’t pirates — tied to nothing, profit their only compass — not the perfect metaphor for the ills of footloose capital?

The bunny, traditionally a symbol of fertility (hence the syncretic Easter association), has whispered into our Captain’s ear and led him to certain death at the stony hands of the monuments of the Rapanui by tempting him with earthly bounty. Fertility has ensured death; Malthus has been vindicated. We laugh at these two pirates’ certain doom because it makes us uncomfortable to know that, within a generation or two, we as well will likely be reduced to cannibalism by the ratty system we have created to quarry, haul, carve and erect so many profane moai — Angry Birds merchandise, Go-Gurt, PT Cruisers, and so on.

Webb has taken these three symbols — environmental ruin, fertility, footloose capital — and constructed a perfect parable to show us the inevitable endgame of our precarious arrangement. Of course it all ends in death and destruction. Of course humanity is brought low by its arrogance, punished for thinking any gods hold us dear, for thinking the Earth considers us anything but parasitic.

Or, perhaps, Webb was just making a joke about bunnies and Easter. And islands. But New Yorker readers voted for this caption in particular, and one hopes they weren’t so easily swayed.

Willy Staley contributes to Shitty New Yorker Cartoon Captions.

Kevin Shields Is 50

Kevin Patrick Shields turns 50 today. Remember a couple months back when everyone was all, OH MY GOD NEW BLOODY VALENTINE RECORD I’M GONNA DIE etc.? Do people still talk about it now here in the future? I’m actually asking, I don’t get out much any more so I’m not sure what The Word On The Street These Days is. Anyway, many bloody returns.

When Will I Make Up All This Lost Sleep?

Do you lay awake some nights with the pillow clamped over your eyes to keep out the light from the streets, your breath labored as you try to set the racing thoughts at bay, listing numbers very slowly and almost drifting off before an errant fear jumps to the front of the line in your consciousness and snaps you back awake? Do you sigh to yourself and resume the slow count, knowing that it won’t really work but trying all the same, because what else are you going to do, it’s way too early to call it morning and you’re already in short supply of sleep because everything you agonize about — and even some things you hadn’t thought to be alarmed by — chooses to make itself fully present at the time of the night when the rest of the world is deep in slumber? Do you add your exhaustion to your pile of problems, creating some kind of self-fulfilling loop wherein your worries that you won’t be able to get to sleep are now the reason that sleep won’t settle down with you? Do you wonder if you can ever catch up on all the sleep you’ve lost? Well, I have some good news: Soon — and a lot sooner than you think, but sadly not as soon as you hope for in those dark moments while your hands rest on your stomach and you cram your eyes closed — you will sleep forever, and nothing will be able to prevent that eternal slumber; all your concerns will turn out to be as meaningless as you try to convince yourself that they are in the moments when they’re the one thing separating you from dreams and you will never wake again. Until then, this might help, but probably not.

Photo by Anneka, via Shutterstock

Ray Manzarek, 1939-2013

I got an email from my friend Matt last night that said, “Well, you won’t have Ray Manzarek to kick around anymore.” This was a reference to an argument we had, Matt and I and another friend, Dave, very late at night this past New Year’s Eve. We’ve known each since grade school, the three of us, and we got into music together in the way that lots of adolescent suburban boys do: classic-rock-first. We all loved the Doors as kids, I had a poster of Jim Morrison in my room in front of which I used to bow my head in prayer. We all mastered the distinctive building-block lettering of the band’s logo — among the best examples of graphic design in the history of rock and roll, if only because of the ease with which it could be drawn on desk-tops and math book covers.

But we all don’t love the Doors anymore. I find a lot of their music really stupid, actually. Schmaltzy melodies, awkward changes, laughable lyrics. With the exception of a few songs that hold up better than others — “Five to One,” “Roadhouse Blues,” “L.A. Woman,” “Riders on the Storm” — they kinda stink. Dave agrees. But Matty, full of New Years Eve cheer, argued for their greatness. His argument was along the lines of, How can we deny the power and beauty and meaning we found in this music when we were 13? And why should we stop ourselves from tapping into those memories, letting ourselves feel those feelings again, that pleasure, that wonder, through the music when we heard it today? I like this argument. And it might mean that Matty’s a smarter person than I am — or, at least, a more generous one, more generous to our younger selves, less hung-up on honing critical judgement and developing an adult identity based in large part in snobbery. One too-much borrowed, maybe, from conventional wisdom based on the writings of famous Doors-hater Lester Bangs. Too proud of my more “educated” belief that Love, one of my very ’60s bands, who came out of the same scene in L.A., but never achieved anyway near the success of the Doors, were so much better.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=k9o78-f2mIM

So, I don’t know… this argument, which is of a kind that I really enjoy, starts to maybe break down along lines of semantics and categories. I mean, yeah, I will always love the Doors in some ways. Jim Morrison stands as a totemic figure: sort of the ultimate rock star. This may be due in large part to the fact that he died (or faked his death and moved to Madagascar and has been living there secretly since) when he was 27 and still so good looking, but nevertheless occupies a large part of my heart. I LOVED the Doors when I was a kid, every song, every album. (Though I remember thinking “Touch Me” was a little silly even then; it sounded so much like bad Frank Sinatra.) They did have a unique sound. One that no band has really ever captured since. How much credit are we supposed to give our younger selves, our still-developing tastes? Maybe more than I usually do?

Anyway, Ray Manzarek, the man most responsible for the Doors sound (and innocent of any blame for their lyrics) died in Germany yesterday after a long battle the even-more-awful-than-most-cancers-sounding bile duct cancer. You can see him being “the adult in the room” in the video at the top of this post, during the recording of “Wild Child” (another song that I think holds up relatively well) from the band’s fourth album, 1969’s Soft Parade. He was 74.