Who Goes Nazi: Bachelorette Edition

“His body is vigorous. His mind is childish. His soul has been almost completely neglected.”

Have you ever watched “The Bachelorette?” I had not, until this week’s premiere of the first season to have a black Bachelorette. I have a hard time watching reality TV. I watch pretty much any drama, sitcom or crime procedural I can find, but reality TV makes me uncomfortable. It seems mean? Like punching down? But I wanted to watch the Bachelorette because I saw some funny tweets about the contestants and I thought maybe it could be an enjoyable diversion in a dark time. As it turned out, it made me almost unbearably uncomfortable, but also somehow was enjoyable. It also is perfect for a delightful “parlor game” invented by Dorothy Thompson in 1941 called “Who Goes Nazi?”

Thompson, a journalist who covered Nazi Germany, wrote about the game for Harper’s (and Leah Finnegan wrote about it again recently for the Outline). Thompson says you can look around any dinner party and determine who would “go Nazi,” given the chance.

Now wait a second, you’re saying. Hold on just one second, Danielle. How are you going to play “Who Goes Nazi?” with the most ethnically and racially diverse pool of contestants in Bachelorette history? To which I say first that I’ve never watched “The Bachelorette” before so I have no idea how ethnically or racially diverse it has been previously and I don’t particularly care to look it up. And second, Thompson says that’s a “preposterous” objection:

It is preposterous to think that they are divided by any racial characteristics. Germans may be more susceptible to Nazism than most people, but I doubt it. Jews are barred out, but it is an arbitrary ruling. I know lots of Jews who are born Nazis and many others who would heil Hitler tomorrow morning if given a chance. There are Jews who have repudiated their own ancestors in order to become “Honorary Aryans and Nazis”; there are full-blooded Jews who have enthusiastically entered Hitler’s secret service. Nazism has nothing to do with race and nationality. It appeals to a certain type of mind.

So, hush. We’re playing.

“The Bachelorette” contestants were basically made for “Who Goes Nazi?” Thompson describes those inclined to “go Nazi” thusly:

Sometimes I think there are direct biological factors at work — a type of education, feeding, and physical training which has produced a new kind of human being with an imbalance in his nature. He has been fed vitamins and filled with energies that are beyond the capacity of his intellect to discipline. He has been treated to forms of education which have released him from inhibitions. His body is vigorous. His mind is childish. His soul has been almost completely neglected.

If you don’t think that describes this cohort of shiny, hairless, over-exercised Ken dolls eager to tell you how much they love The Rock and having threesomes, I don’t know what to do with you. You’d probably go Nazi, if you haven’t already.

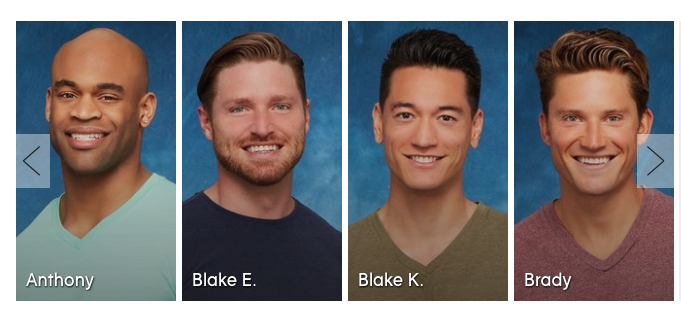

I’m not going to go through all 31 contestants because that’s crazy and I honestly can’t fathom knowing all of their names until Bachelorette Rachel Lindsay has killed off, I mean sent home, at least half of them. A selection is adequate.

Adam, the schmuck who brought a doll — Would go Nazi. See Thompson: “I think young D over there is the only born Nazi in the room… He spends his time at the game of seeing what he can get away with.”

Alex, who relayed that his mom thinks he has an IQ of 180 — Alex. ALEX. IQs are determined by tests, not by mothers. “My mother said I graduated with honors.” What does your transcript say, Alex? See Thompson: “Young D is the spoiled only son of a doting mother. He has never been crossed in his life.” Alex would go Nazi.

Blake E. — First of all, there are two Blakes, proving the producers would definitely go Nazi, if they haven’t already. But we’ll come back to that. Blake E. is the one who bragged at considerable length about the “amazingness” of his penis and also indicated he can only have sex for 30 minutes every 24 hours. Blake. That is not amazing. See Thompson, quoted earlier: “His body is vigorous. His mind is childish. His soul has been almost completely neglected.” I’m disinclined to even allow that his body is vigorous. Would go Nazi.

Bryan, the eager Spanish speaker who claims to be “trouble” — After telling Bachelorette Rachel Lindsay he is “going to be trouble,” Bryan told her he’s “good with [his] hands,” made her speak Spanish back to him and then grabbed her face and forcibly kissed her. We don’t even need Thompson here. We can use that quote often attributed to Maya Angelou: “When someone shows you who they are, believe them.” Would go Nazi.

Dean — Dean is the putz who told Bachelorette Rachel Lindsay upon meeting her some months prior to this episode, “I’m ready to go black and never go back.” That alone had him in the “would go Nazi” column. But! A Bachelorette-savvy friend directed me to Vulture’s Bachelorette recapper, Ali Barthwell, whose recap of this episode made note of Dean’s preoccupation with finding out if Rachel thought it was okay that he said that. Barthwell speculates that a producer must have told him to say the inane statement because “if you’re the type of white guy who says that of your own free will, you don’t backpedal.” Good point, Barthwell. Producers would definitely go Nazi. Dean is still a question mark. For now.

Jonathan, who tickled Rachel without permission upon meeting her — There was so much unacceptable behavior in this television event. The doll. The guy who identifies as “whaboom.” Jonathan’s aggressive entrance was one of at least three times when Rachel could justifiably have yelled, “Security!” Thompson: “He spends his time at the game of seeing what he can get away with.” Would go Nazi.

Kenny — Kenny is a pro-wrestler who has a daughter. He seems nice, actually. And he wanted to burn the doll. Kenny maybe wouldn’t go Nazi. TBD.

Lucas, a.k.a. “Whaboom” — Lucas is a travesty. He’s an affront. He is an anthropomorphized gimmick. He is reality TV producer catnip and he loves it. Lucas would 100 percent go Nazi. Lucas would go Nazi multiple times if he could.

Milton — Milton kept growling at Rachel. Why, Milton? Apparently the doll, “Whaboom” and the tickler were acceptable, but Rachel drew the line at growling and sent Milt home at the end of the first episode. Milt cried about all the outfits he wanted to wear on TV. Milton would want to go Nazi, as long as there was no uniform. Whether the Nazis would have him is another question.

Mohit — Mohit visibly freaked out when what’s-his-name and Rachel made out. Mohit actually yelled, “No, back off!” aloud, giving voice to many of us watching at home. Mohit then got too drunk. Understandable. Mohit probably would not go Nazi. Unfortunately, Rachel sent him home. Sorry, Mohit.

The Producers — The producers (probably) made what’s-his-name say that inane comment, had Rachel sit down opposite that fucking doll and pretend to talk to it and, judging by the look that flashed across her face before she gave him the rose allowing him to stay, forced her to keep Whaboom on the show for at least one more episode. Entirely possible that this show is produced by Joseph Goebbels reincarnated.

Danielle Tcholakian is a writer in New York City.

Dear Highly Successful People: Stop Talking About Your Failures

Failure is a luxury.

I was warned to beware my thirties. I was told that this is when everything I took for granted as functioning well would begin to stop. Over a year ago, I mis-aimed a jump over a puddle and rolled my ankle, and it still clicks when I walk. It’s not that when I turned thirty things suddenly started breaking down, it’s that recovering from falls now takes longer, if it ever happens at all. The moment you realize that recovery is no longer a guarantee is scary as hell. But as disheartening as this realization is, failing to recover from injury is not nearly as harrowing as the prospect of failing to recover from failure.

Recently a colleague forwarded me an article in the Washington Post about Johannes Haushofer, a professor of Psychology and Public Affairs at Princeton who wanted to add a shade of realism to the picture of his promising career. So he decided to post his own “CV of failures.” It includes all the jobs he didn’t get, all the articles that were rejected, as well as a hilarious nod to the “meta-failure” that crowns this masterwork: “This darn CV of Failures has received way more attention than my entire body of academic work.”

It also received its fair share of attention from my coworkers, all of whom are academics at the beginning of their careers. Their responses were unanimous: “Shit. This guy’s failure CV is more impressive than my real CV.” For a young scholar, reading a CV of failures by a faculty member at an Ivy League institution must be what it’s like for an off-Broadway actor to read about Leonardo DiCaprio’s unsuccessful auditions. As one friend put it, “He can publish that cause he’s at Princeton.”

It was just as I was entering my thirties and simultaneously beginning my life as a professional, a husband, and a father, racked with stress to find a job and support my family, that I started to notice successful people talking about failure. And boy, did I resent them for it. The most prominent example in recent years is probably Conan O’Brien’s 2011 Dartmouth commencement speech. It is a beautiful work of prose that ends with an account of how O’Brien dealt with the disappointment of almost getting to host “The Tonight Show.” And of how failing to achieve his lifelong dream liberated him from the requirements of success: “It is our failure to become our perceived ideal that ultimately defines us and makes us unique,” says O’Brien. “It’s not easy, but if you accept your misfortune and handle it right, your perceived failure can become a catalyst for profound re-invention.”

When I first heard O’Brien’s speech, I resented it for the obvious reasons. Re-invention sounds lovely when you’ve already achieved a level of success that most people only dream of, less so when you’re trying to begin a career. It wasn’t that O’Brien’s optimism sounded hollow, but that it sounded a lot like an outdated version of my own. As a college student, I focused less on grades than on self-discovery. As a professor, I gravitate to students who do the same. And I tell my undergraduates not to be afraid to take risks, because no matter how well you think you’ve prepared, adulthood will find its nefarious way of surprising you — and this is the best thing about it.

In 1982, Joyce Carol Oates published an article in The Hudson Review that examines the role failure will play in the lives of highly creative people. “The artist,” she says, “perhaps more than most people, inhabits failure.” Nothing is more demoralizing than scanning the work you struggled to create and realizing that you would have done better to keep quiet. Anything that’s ever any good only got that way if its maker realized what was once so bad about it. As Hemingway so delicately put it: “The first draft of anything is shit.”

But Oates has more worldly things to discuss than the value of revising. Her thesis is not just that great works of art begin as failures, but that great works of art are oftentimes created because artists begin as failures. She cites Henry James’s unsuccessful attempts at dramaturgy, William Faulkner’s inadequacies as a poet, all of which eventually spurred them to create masterpieces of American fiction. James Joyce began as both a mediocre poet — see his collection Chamber Music — and a pedestrian novelist. If his earliest attempt at a bildungsroman, Stephen Hero, had proven successful, Oates argues, he never would have taken its themes and rewritten them into A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man, which is undoubtedly one of the great works of English prose. Oates is asking the same question Conan O’Brien’s speech is declaring:

“Is there, perhaps, a very literal advantage, now and then, to failure? — a way of turning even the most melancholy of experiences inside-out, until they resemble experiences of value, of growth, of profound significance.”

Yes. There is. But let’s not pretend that failing to achieve success in a career is the same thing as failing to make a masterpiece. Revising takes time and time costs money. “Whether you fear it or not,” O’Brien concludes, “disappointment will come. The beauty is that through disappointment you can gain clarity, and with clarity comes conviction and true originality.” True. But it’s success that grants you the money and the time necessary to gain the clarity and conviction to achieve that originality. As much as failure can lead us to wrangle and raze our mediocrities, failure can also force us to settle down into them. The clarity and conviction that comes with self-improvement happens on unpaid time. Only the lucky few who can afford these trials, or who are willing to make sacrifices for their wageless labor, can justify devoting so much effort to themselves.

Joyce’s unpopularity “protected” him, writes Oates. When I read this in my twenties, I found Oates’s argument inspirational. Today, I can’t help but think of Joyce’s wife Nora, as well as their two children who grew up in poverty because their father’s writing never paid the bills. It is all very heroic, this portrait of the artist laboring in penury, but the picture loses its glamor when you glance in the direction of the people affected by the artist’s dedication to his own originality.

Oates says a lot about authors whose careers might have been mediocre had they achieved success early on. But she doesn’t mention those writers whose triumphs granted them the time and money to spend their workdays focused on their careers. F. Scott Fitzgerald was a star early on and a flop later. His two greatest works, The Great Gatsby and Tender is the Night, appeared at the latter end of his writing life. They were such commercial failures that Fitzgerald wasted out his remaining days scrounging for screenwriting work in Hollywood.

However, it is doubtful that Fitzgerald would have had even these opportunities had his first novel not established his name. Had This Side of Paradise not done as well as it did, Fitzgerald would not have earned the kind of money he did over his career, and he might never have found the wherewithal to dedicate himself to his two later masterpieces. He might not have even married the woman who provided so much fodder for his work — after all, his first novel was written in part to convince a glamorous young socialite named Zelda Sayre that its author was successful enough to be considered marriage material. Who knows what fate might have awaited Fitzgerald had he been blessed early on with the freedom of failure. Perhaps America would have an even greater Gatsby. Or maybe just another advertising executive’s unwritten autobiography.

Failure is a luxury. It’s a luxury that some are born with and get to keep, while others never get to experience. It’s the luxury that many of us enjoy when we’re young, but learn that we’ve lost as the encroaching exigencies of adulthood take over. Anyone who is past a certain age and remains steadfast in their attempt to break into a cutthroat industry understands this. Anyone who has ever worked as a waiter in L.A. or New York knows this. What’s scarier than learning that the fifty-year-old server you work with was once a valedictorian at Duke, or a finalist for a film with De Niro? Sure, failure can keep you immured from a public’s expectations, allowing you to grow into maturity. But sometimes what you need to succeed isn’t more anonymity but a few more years of freedom from the responsibilities that come with maturity. There comes a time when, for whatever reason, you literally cannot afford to devote any more time to yourself. And this is the moment when one’s failures threaten to define themselves into one’s life as failure itself.

It feels so otherworldly then, to hear these successful people go on about the value of failure. All these Casanovas lamenting their loneliness — Could their realities really be the same as mine? In the same way I wonder: Can this person in his thirties really be the same guy who was so optimistic in his twenties? This is not to discount the struggles that even the successful undergo. Nor is it to discount how much I myself have learned from my own failures. But learning from your misfortunes is not the same thing as benefiting from them.

As much as any mature adult understands that even the most fêted have experienced disappointment, disappointments don’t count as failures. Once you’ve achieved a certain degree of success, I’m sorry, but those past failures no longer qualify. “The spectre of failure haunts us less than the spectre of failing,” writes Oates. I could not disagree more. I am not scared of failing and continuing to fail. I am scared of not having any more chances to fail.

Failure is only ever positive after you’ve achieved the kind of success that miraculously grants it the veneer of self-improvement. Whereas if you’ve reached your forties and you’re not being hailed as a genius, or being asked to deliver commencement speeches at important universities, or working at an important university, then you are probably wise enough to understand the truth no one tells people on graduation day — failure only counts as progress if you can afford the luxury of not having to look ahead.

A supposedly highly successful man once said: “I don’t like losers.” Of course not. No one does. After all, losers are losers for a reason. And the worst thing about them? They remind us of the truth we forget when we feel like we’re winning: All our triumphs, especially the ones we worked the hardest for, are very much based on inheritance.

“Most of what I try fails,” writes Professor Haushofer in his introduction to his parvum opus, “but these failures are often invisible, while the successes are visible.” As a result, he says, people “are more likely to attribute their own failures to themselves, rather than the fact that the world is stochastic.”

In probability theory, that which is stochastic may be analyzed but not necessarily predicted. The word entered into English in the seventeenth century from the Greek stokhazesthai ‘aim at, guess,’ from stokhos ‘aim.’

Which is exactly what I tell people when they ask me how I hurt my ankle that one night way back when: I aimed wrong, that’s all. There was no way to predict in which direction the ground would be moving.

James Nikopoulos teaches literature at Nazarbayev University.

The Men of Hammacher Schlemmer

Are they really happy?

From its founding as a hardware store on the Bowery in 1848, through its underground days as a minter of “copperhead” tokens during the Civil War coin shortage, through its twentieth-century expansion into gadgets and novelties, Hammacher Schlemmer has never stood still. The company’s “brand” is its very lack of one, the laughable variety and incongruity of its thousands of products. Along with its downmarket cousins SkyMall and the Sharper Image, its name has become a byword for the ludicrous contraption, the elaborate gadget posing as a basic necessity.

Yet for all its reputation as an emporium of the ridiculous, the images in the Hammacher Schlemmer online catalog are often dully direct, unadorned shots of the product for sale. Even when the items are as odd as the Golf Cart Hovercraft or the Levitating Lamp, in situ, they blend in with other, ordinary objects of home and office.

But when depicting products that require human interaction, these photographs burst into life. And usually, that life comes in the form of lone men, operating or holding or transporting the product, displaying its uses with evident joy. Here is the man piloting his Voice Controlled Drone; the man hefting the Pepperphile’s Peppermill; the man reclining blissfully with his Stress Reducing Mind Spa. Men, it seems, are the heroes of the Hammacher Schlemmer story of invention and discovery, the dreamers of its dreams. Women also appear in the company’s catalog, of course. But all too expectedly, their wares tend toward the personal and domestic: see the Cordless Neck and Shoulder Heat Wrap or the Planter and Birdfeeder Pulley System. The crazed thrill of discovery, the spark of obsession, the delight in the new, are, at least in the Hammacher Schlemmer imaginary, male properties.

And specifically, dad properties: so-called dad music, dad bods, and dad humor have become cheap memes, but the men of Hammacher Schlemmer make vivid the socially specific reality implied but obscured by this prevailing idea of the “dad.” These men are uniformly and unmistakably suburban, white, middle-aged, middle-class. From their backyard pools to their khaki slacks, they embody the frumpy maturity and modest affluence that, probably not for better, have become synonymous with contemporary fatherhood.

And true to this archetype of “dad” as lovingly goofy and corny, the men seem to know only one emotion: delight. People in advertisements are always happy, but these men’s wide smiles and warm eyes speak to a deeper dad satisfaction — the pleasure of the sound purchase. The wise investment. Planning, providing, and prospering. But are they really happy?

Looked at more closely, the men of Hammacher Schlemmer seem out of time and place, unmoored from physical reality. In maybe half of these images, the men inhabit no place at all: the setting is an empty white expanse, an abyss that blends into the surrounding blankness of the webpage or catalog spread. Despite his boyish grin, the man in the navy polo shirt and chino shorts cruises his 12 MPH Cooler into nothingness; the man in the light pink button-down and khaki pants sharing a laugh with his Celebrity Robotic Avatar seems suspended in a Beckettian vacuum. And even when the photographs depict “real” places, their details often look flattened or fake — oversaturated, blurred, subtly unconvincing. In a scene showing the Giant Rubber Duckie, man and duck have been pasted onto a too-blue pool in a too-perfect McMansion backyard. Rather than reality, it’s like we’re seeing the man’s duckie dream, the vision that moved him to pay $229.95 plus shipping (“We regret,” the product page announces, “that this item is no longer available”).

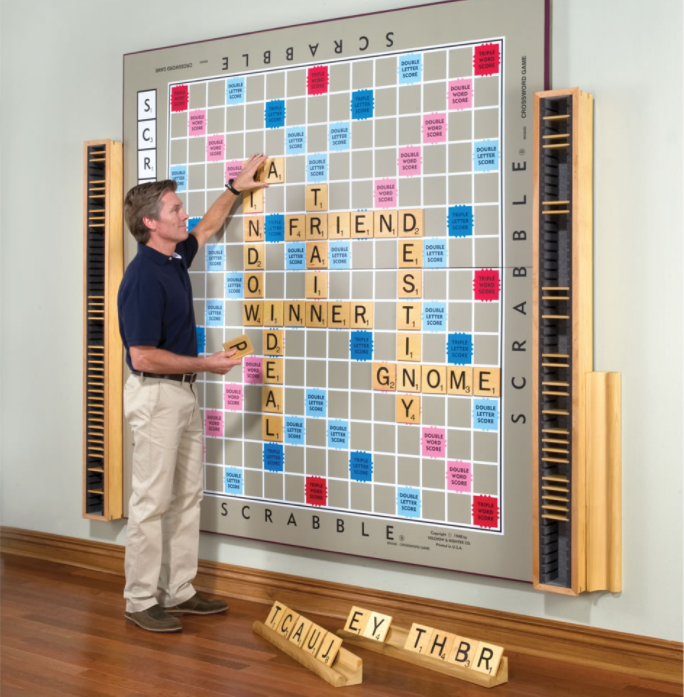

The more poignant motif uniting these men, though, is their solitude. Though real fathers would be eager to share their zany purchases with their family, the men of Hammacher Schlemmer are almost invariably alone with their toys. Scrabble is a game few people would enjoy alone, but the man absorbed in the World’s Largest Scrabble Game — at $12,000, surely an investment worth sharing — appears only to be playing himself. Even a rare exception to this isolation, the two men leaping and bouncing in the Human Pinball Suits, seem to enact an almost too-blunt allegory of the greater barriers that separate them: though their bulbous encasements collide, their truer selves remain trapped under layers of air and plastic. (The symbolism darkens further when we notice the men look nearly identical: twins, maybe — or two sides of the same man, slamming into himself.)

Of these men, only one makes no effort to smile: seated on a plane, with the Rechargeable Personal Air Purifier looped like a bolo tie around the collar of his beige Oxford shirt, he gazes quietly and pensively out the window, into the beyond. That he appears to be one of only two passengers — a shadowy figure (death?) lurks several rows behind him — on an otherwise empty commercial airliner only deepens this meditative mood. Far above and away from home, family, and work, he seems readier than the rest to confront and contemplate the abyss, albeit in the security of a private cloud of purified air.

We can guess what he might be thinking about. All of these products are profoundly useless. They meet unfelt needs, satisfy unknown desires. They require an alternate existence, another medium of being, for their pointless features to look purposeful. The drama — if you’ll let me call it that — of these images is the men’s lonely struggle for utility, for necessity, for purpose. It’s easy to see in their crinkled eyes and glinting smiles the burden of middle-age ennui, the toll taken by years of work, childrearing, mortgage payments, lawncare.

In the white voids, beige beds, and green backyards of this universe, the men of Hammacher Schlemmer confront not just their purchases, but themselves. (Sometimes, in the case of the Best Fog Free Mirror, literally.) Their private terror is the struggle to prove that they are not similarly useless, that they endure disappointment and insecurity, shell out $9,950 for the Climbing Wall Treadmill, in the name of a worthy and manly fight for fulfillment, family, fatherhood. The catalog copy only reinforces the masculine anxiety in these images: the Pepperphile’s Peppermill, for instance, “holds over 2-lbs. of peppercorns and towers over table centerpieces or double magnums of wine, conveying the peppercorn’s dominance over all other spices in your pantry.”

The Hammacher Schlemmer website includes an entire section labeled “The Only,” featuring products unavailable anywhere else: the Only Unkinkable Garden Hose, the Only Music Box Espresso Machine, the Only Seven Person Tricycle. Let’s take this all the way: these men live in the realm of The Only. Theirs is the soul-consuming masculinity of allegiance to self-control and self-invention, a drive for purpose, a search for an imagined utility, as infinite in possibility as it is empty of meaning. They are the Only Men.

Colin Vanderburg is a Brooklyn-based writer and an assistant editor at Monthly Review.

["Anyway, Here's Wonderwall" Voice] Anyway, Here's Beethoven's 9th

I took a Classical and Romantic Music History class when I was in college. Like, first of all, can you tell? Is it not the most obvious thing about me, beyond even writing this column? Anyway. One time, during one of my Classical and Romantic Music History classes on a sunny Friday afternoon, our professor opened up all of the windows in the classroom and put on the Leonard Bernstein 1969 recording of Beethoven’s 9th Symphony and we listened to it in silence. That was it. The entire class. When it was done after about 50 minutes, he gave us a nod and we left.

It ought to be clear that I cannot file a one paragraph column that says “listen to Beethoven’s 9th and then you can close this tab,” but I can do my best to walk you through what is one of the greatest achievements in this history of culture without so much as fully ruining the integrity of the piece by over-explaining it. Does this include a brief overview of the achingly sentimental and sad short story I wrote about Beethoven in my sophomore year fiction class called “9th” that was ultimately REJECTED from my college’s literary magazine? We’ll see.

What is there to know about our old friend Ludwig van at this point in his life? Well, the composer had been completely deaf for nearly eight years by the time his 9th premiered in Vienna in 1824. The anecdote that always struck me about the premiere of this piece was that Beethoven had conducted the piece himself, sort of. The composer ultimately shared the stage the resident conductor Michael Umlauf (good name), who had instructed the orchestra to respect but ultimately ignore any of Beethoven’s gestures throughout the night. It was a combination of age and deafness and being totally absorbed in his own music that led Beethoven to conduct well past the finale of the symphony, forcing one of the singers to turn the man around so he could see but not hear the standing ovation given to him.

IS THAT NOT THE MOST FUCKED UP AND TRAGIC THING YOU’VE HEARD IN SOME TIME?

Because it is one of the most famous pieces of music of all time, it’s likely that at least the very beginning of every movement is going to sound familiar to you. The opening quiet refrain of the first movement, Allegro ma non troppo, un poco maestoso (quickly but not too quickly, and a little majestic), and sounds not unlike an orchestra warming up before the first big blast of sound comes through. To me, the 9th has always been about the relationship between struggle and joy, the struggle for joy. No doubt this piece, as well as many others, had been an immense struggle for Beethoven; how do you compose something — let alone something as iconic and wondrous as this — once deaf? Similarly, is that feeling of perseverance in the face of struggle not one of the greatest feelings of all time? (This is what I tell myself as I’m cleaning my apartment.) This movement itself is in sonata form (the way a full symphony often is), but when the original theme returns, it’s a major key versus a minor key. You’ve persevered!

You 100% know the opening refrain to the second movement, Molto vivace — Presto, a quick and frantic dance of joy. This is one of the most hummable themes in the history of music (except, of course, well, we’ll get there). I do not think Beethoven’s 9th is aggressively easy to listen to — not because of its sound but more because of its length and scope, but this second movement is perhaps the easiest to latch onto. By the second minute of it, you know the essential beats and themes.

The Adagio molto e cantabile is reverent (not to be confused with the BAD MOVIE that Leo DiCaprio UNDESERVED won a BEST ACTOR OSCAR for), sincere, and peaceful. Beethoven takes his time lulling you into a sense of comfort before his big finale. The 9th is widely praised for its finale, but I often feel like the Adagio is the real MVP. It gets at the real heart of what set Beethoven apart, which was his ability to create these immensely worthy and noble pieces of music that almost burst out of thin air. The Adagio barely feels like it was written so much as it already just existed, merely crafted and shaped at the hands of someone who loved it dearly.

The duration of the fourth movement (with so many musical directions it’d be ludicrous to name them all here), is 24 minutes: a symphony in and of itself. Its first seven or so minutes are like a prologue to the rest of the piece. It starts in a relatively dark and foreboding place, but quickly reveals itself to be something else entirely. Bursting through a dialogue between the low strings and the woodwinds, at around the 2:48 mark, is the part literally the whole world knows, Ode To Joy. This is Ode To Joy, the origin of it, the famous piece, the thing that every kid who learns piano knows how to play, and one of the most joyous (I’m not sorry!!!!!!) melodies of all time. After the prologue, however, Beethoven does something literally insane which is bring in a full choir and four soloists. The text of Ode To Joy is from a poem of the same name by German poet Friedrich Schiller, and for the remaining twenty minutes of the symphony, it becomes something of an opera. This was lunacy at the time. It was fucked up and weird. Of course now you’re just like, oh, this is why Wagner exists.

This final movement is so enormously grandiose it’s hard to even wrap your head around it. My best advice: listen to it. And by the time you reach that final minute and a half with its timpani and crash cymbals, it’ll just all crystalize for you. It practically flails with self-importance, but hey, it’s deserved. Can you think of something else like this? It’s impossible, because… the 9th is it, in every sense. It’s the peak of a movement, truly, as well as Beethoven’s statement on why he persevered through his own struggle. It’s why it still resonates, why your brain knows it even if you think it doesn’t, because the feeling of it is so universally known, as if he conjured it out of happiness itself.

Fran Hoepfner is a writer from Chicago. You can find a corresponding playlist for all of the pieces discussed in this column here.

Superpitcher, "Burkina"

Confused? You’re not the only one.

What are the questions you ask yourself these days when you’re so stunned that all you can do is wonder about why we are where we are and how we got here? Mine are usually, “Where am I? Why am I here? How did I get here?” but sometimes I allow myself a, “How long can this go on?” Well, never ask yourself a question you already know the answer to. It just doesn’t work out well. In all cases I think I would prefer to remain confused, but life just isn’t that sweet. Anyway, here’s something new from Superpitcher, which is. Enjoy.

New York City, May 22, 2017

★★ The rain had paused for the walk to school. The cool air was agreeable; the sidewalks were drying out but the trees still held in the dampness on the schoolyard. A mat of shredded green leaves lay at the foot of the fence. When it did return, the rain was moderate, with drizzle in it, not heavy enough to create problem puddles even in the bad drainage of Union Square. After a day of excessive air conditioning and dim light through the window, the dense and wet atmosphere in the streets had come to seem warm and welcoming.

Why You Should Watch "Bite of China" Instead of "Chef's Table"

It’s a better show about food.

While all of humanity and Hollywood are busy mining British television for the next obscure detective series hit starring a skinny white guy with a sharp nose, China’s CCTV has made the best show on the small screen. “China Central Television?” you may ask, doubtfully, if you, like me, were first introduced to the channel (channels, really — there’s like 30 of them) in a Beijing hotel room, watching the same three shows over and over again: pandas, soap operas, potentially biased state-run news. Yes, because they also produced “Bite of China.” Even The Guardian called it “the best television show about food ever made.”

You might not think that you need to understand why Siberian elm flowers and green field snails are part of China’s culinary culture, but that’s because you haven’t watched this show yet. You might be too busy watching “Chef’s Table,” which I’m happy to admit might be the pinnacle of American food television, but that’s a dubious honor, like being at the pinnacle of American maternity leave policy.

But here’s the thing about “Chef’s Table”: The Emmy Awards and Netflix watchers alike have heaped praise upon this show that glorifies the work of top chefs around the world. The dramatic, documentary-style, food-porny shots keep diners drooling. But they’re drooling over people making incredible food with every resource imaginable — astronomically expensive meals that wealthy diners fly around the world to eat. If you want to understand the most truly amazing things people do with food, you need to look low, not high.

“Bite of China” is the poor man’s “Chef’s Table.” Not that the production values are low-grade or the cinematography hokey — in fact, it’s chock-full of absurdly sexy shots of temptingly delectable food with visuals and narration that both recall the BBC’s “Planet Earth” — but in that it profiles the little guy, the family selling five-cent buns, not three hundred-dollar dinners. It focuses on the people who make food in rural and urban China, carrying on regional food traditions and biking their products two hours to the nearest town to sell, foraging for rare mushrooms in the high mountains of Tibet, picking lotus roots in knee-deep water. It’s “Planet Earth” for the food-lover, “Chef’s Table” for the proletariat, Jiro Dreams of Sushi for all of China’s vast cuisine.

I was sitting at a banquet table in Hangzhou with my husband and his Chinese co-workers when I first learned of the show. “You’re a food writer, you order,” they said, shoving a menu in my hand, which was how we had ended up with the still-moving drunken shrimp on the table, splashing red wine sauce across the white plates as they flapped their tails, and a dozen people looking at each other nervously wondering who would take the first bite. This is a common expectation: that food writers know about all foods everywhere. But more shocking to them than the fact that I couldn’t order us a decent banquet from the photo menu was that I had never seen “Bite of China” — or as the Chinese name translates literally, “China on the tip of the tongue.”

When the stunned silence ended and somebody finally bit into the (surprisingly delicious) shrimp, a ripple of conversation started. First thing tomorrow, we would be escorted to a restaurant across town that had been featured on the show. By the time we arrived at our hotel in Shanghai the next afternoon, they had Taobao-ed (think Chinese Amazon, but bigger and better) the box set of both seasons — the entire series, plus a companion recipe book (sadly only available in Chinese) — directly to our hotel, which just happened to have a DVD player. (Lest you criticize me for spending my time in Shanghai watching movies instead of exploring: I was traveling with a four-month-old. There was a lot of indoor time.)

We watched as chefs made longevity noodles in Shanxi and artisans cured giant hams in Jinhua, sat riveted by the process of picking bamboo shoots and by the intricate multi-tiered preparation of nine-layer cakes. The foods that danced across the screen to the stilted accent of the English dubbing ranged from cobweb-like hairy tofu to simple handmade dumplings, the shots from sprawling overheads of entire waterways to the tiny water droplets cascading from a single garlic sprout.

The stories, like the camera work, pan from micro to macro to give a full picture of the country’s varied and disparate styles of cooking. Even though “Bite” is limited to a single country, it manages to include more diversity in single episodes than the entire “Chef’s Table” series. In a Wall Street Journal story on comments posted to Weibo (think Chinese Twitter), a common complaint was that it focused too much on minority and border cuisines, and not enough on the majority Han.

To me, that’s part of the appeal: a deeper exploration of sides of the cuisine that even the most aggressive and adventurous traveler would have trouble digging up. It doesn’t just show off the food: it bores to its center, looking at the people who make it, eating with them, following them on the job, and seeing how a lifetime devoted to the food affects them. It demonstrates the “why” behind the traditions — like how lamb fat in a Xinjiang polo (pilaf) dish pulls vitamins from the carrots — and then illustrates it with the kind of intensely appetizing shots that make your stomach rumble and your brain immediately contemplate booking flights to Kashgar.

In some ways, “Bite” shares the element of out-of-reach temptation with “Chef’s Table”: with the former, it’s solely geographical, with the latter, also financial. But where the focus of “Chef’s Table” is on the singular achievement of an individual in each episode — “this guy [or occasionally gal] is special” — “Bite” comes across with a more general message: Chinese food is diverse and incredible. So, while I can’t go out tonight and buy intricately carved jujube pastries in the shape of flowers any more than I can fly to France to sit at Alain Passard’s table, I can order in some noodles and dumplings and at least eat one tiny piece of the same giant tradition displayed as part of the best food television ever made.

While CCTV has Bite of China on their website for viewing, it is finicky, and I’ve found that I have better luck on YouTube: Season One, Season Two. Amazon also has the first season free for Prime members or for purchase, but it’s a subtitled version, and this is one of the few cases where the dubbed version is better. They also have the box set for sale.

Naomi Tomky is a Seattle-based freelance food and travel writer and the world’s most enthusiastic eater of everything.

Guess The Expletive

Jared Kushner in the ‘Times’ edition

The best game to play in the New York Times is not, as many people might think, the daily crossword puzzle. It’s “guess which swear word the squeamish editors at the Times decided we couldn’t handle.” Today’s puzzle comes in a very good piece of reporting by Alec MacGillis on the “distress-ridden, Class B” apartment complexes owned by Kushner Companies.

Cox stopped cooking for herself and her son, not wanting food near the sink. A judge allowed her reduced rent for one month. When she moved out soon afterward, Westminster Management sent her a $600 invoice for a new carpet and other repairs. Cox, who is now working as a battery-test engineer and about to buy her first home, was unaware who was behind the company that had put her through such an ordeal. When I told her of Kushner’s involvement, there was a silence as she took it in.

“Get that [expletive] out of here,” she said.

Jared Kushner’s Other Real Estate Empire

“Fucker?” “Motherfucker?” “Asshole?” It has to be a noun, right? One word. “Asshat?” “Fuckface?” “Shithead?” Maybe “dickwad.” Or the less popular “dickweed.” Portmanteau or not? It couldn’t be “son of a bitch” because they print that and it’s a lot of words—the way Cox says it it sounds like it just sort of rolled off the tongue. “Fucko?” You can really pick your own word. I’m going to go with “fucklord.” Choose your own adventure.

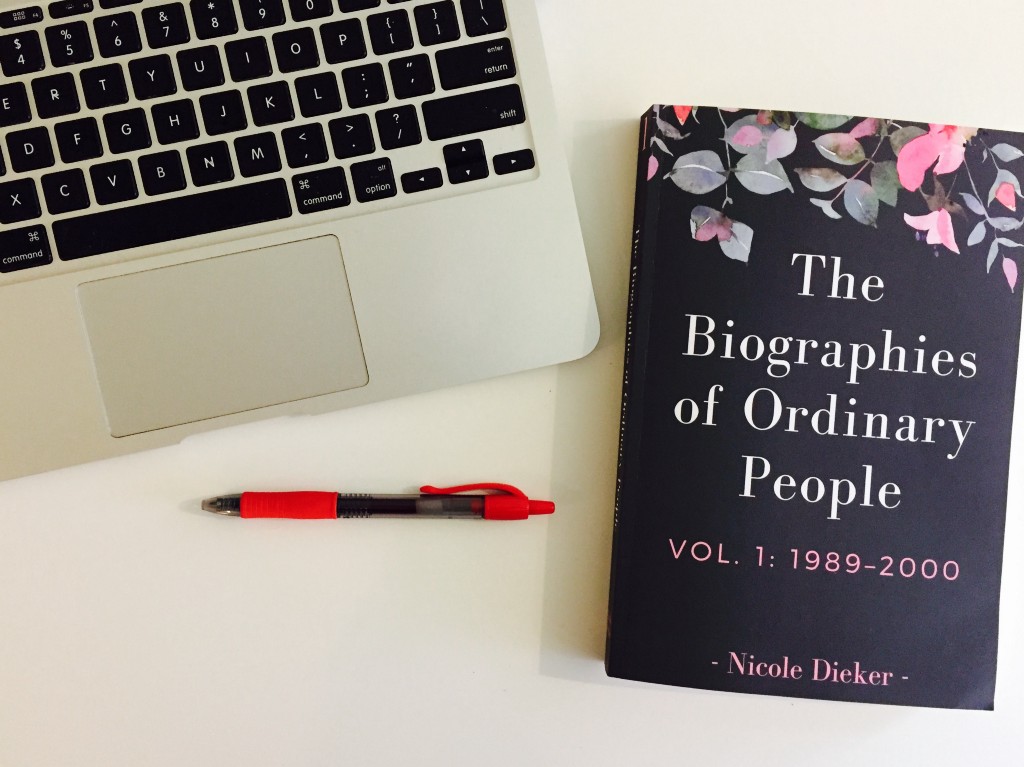

Never Write a Novel With an En-dash in the Title

Lessons from a literary debut.

Never write a novel with an en-dash in the title. You’ll finally learn the alt code, after months of searching “en-dash” in another tab and copying the result every time you type your own novel’s name, but the real issue is that you’re going to be filling out a lot of forms, on Kirkus and Indiebound and Amazon, and half the forms will automatically convert your en-dash into a hyphen, and you’ll wonder if everyone who reads your title on one of those websites with one of those forms will assume you don’t know how to appropriately punctuate a date range.

You probably shouldn’t have a title with two sets of colons, either. You hadn’t planned to have to type The Biographies of Ordinary People: Volume 1: 1989–2000 into all of those forms, because you always visualized it the way it would look on your novel’s cover. Only one colon, and a hard return. (Some of the forms let you submit the post-hard-return half of your title as a subtitle, and you wonder if splitting the title in some instances but not others will mess up your SEO.)

Mention the title as soon as you can, though, and give a link. Editors can swap your link for one that includes their publication’s Amazon affiliate code, you’re all for everyone making money, but the link has to be there. Nobody’s going to run their finger over the title of your novel, all nine words and two colons, and tap Copy. New Tab. Paste.

Readers will wonder what your book is about and you will have to figure out a way to tell them. Most books are about how to live; that’s why you wrote this one, anyway, to ask yourself the question of how to live and see if you can answer it by imagining characters living in a variety of ways. But you can’t say that. Saying your book is about how to live is even more pretentious than putting an en-dash and two colons in the title.

You could say it is a Millennial novel, which is true, but that will make some people presume that it’s all about tech and selfies and not buying paper napkins. Douglas Coupland but pink. You could also say it is a contemporary Little Women, which is what you say most often, because that is the other reason why you wrote it. “I wanted that type of story to exist,” you say again and again, “in our own time period.”

Some people will automatically assume you’re writing “domestic fiction,” while you think of it as “a look into the different paths young women choose for themselves as they move from childhood to adulthood.” There used to be stacks of those types of novels, Wilder and Lovelace and Montgomery and Alcott side-by-side in boxed sets, and then women stopped writing them—until Ferrante, whose Neapolitan Novels become popular while you are in the middle of your first draft. You avoid even looking at them until you’re done with your revisions, and then you read all four in two weeks.

You’ll do an interview in which your first volume is compared to Ferrante’s, and you will wonder how to feel about that. More specifically, you’ll wonder if you should feel bad for feeling so happy. This is exactly what you want, which means it feels shameful. To be worth the comparison. Or worse—to have your novel’s merits inflated, which would mean your happiness would be about something that isn’t even true.

After all, not all of the reviewers were so complimentary. Kirkus will give your writing a respectable amount of praise but will also ask why everyone in your novel is “so polite.” Like Wilder and Lovelace and Montgomery and Alcott and (assumedly) Ferrante, you set your novel where you grew up: in the rural Midwest, where politeness is as stifling as humidity. You will learn there is at least one part of your novel that readers and reviewers may not understand. You wonder if that means you have written it poorly.

At this point you should mention that Foreword Clarion Reviews gave your novel five stars. “The Biographies of Ordinary People contains artful writing and delicately drawn characters who navigate through the universal tragedies and triumphs of everyday life. This first volume is deeply satisfying.” You can breathe in and out on those two words, like a meditation. Deeply satisfying.

You should never lead with the fact that you’re self-published. You can get really far without mentioning it at all. When you’re sending out ARCs or setting up readings at bookstores, just give them the title and the link and your five-star review. Or write that you’re published via Pronoun, and let them click the link and learn that Pronoun is a publishing service for independent authors. (Which, by the way, you will recommend thoroughly.)

You can, however, use the self-publishing factor as a marketing tool—plus the fact that you funded the draft of your novel through Patreon. Plenty of people want to know how to write a novel and plenty of people want to know how to earn money by writing a novel, and you’ve done both. This means you can frame your novel as a success before it is even published.

Whether your novel will be a success is still to be determined—though you can guess already that it might not, five-star reviews and Ferrante comparisons aside. It is successful because you did it. It is financially successful because you have not yet spent more, to publish and promote the novel, than you earned from the Patreon project. You can say all of these things but you know there is another marker of success out there—well, multiple markers, because you know that the trad publishing world counts a “successful” literary fiction novel as one that sells 3,000–5,000 copies, and you also know that there’s the type of success that derives from momentum; from being good and having everyone talk about you at the same time.

You do not think you will have that kind of momentum, for the same reasons you weren’t ever popular in high school.

You will eventually type “how does novel win Pulitzer” into Google and learn that anyone can submit their novel to be considered for the Pulitzer Prize, they don’t care if you’re self-published or not, all you need is $50 and enough faith in your own work. You do not think you will win the Pulitzer, but you know that you won’t win unless you enter. Plus, it’ll ensure your novel is read by at least one more person who cares about literary fiction from both a narrative and structural standpoint, and that’s worth the entry fee.

You can imagine winning, but you can’t imagine winning, to turn the phrase. You didn’t even know that what you had written was technically called a bildungsroman until after you had written it, and the one time you tried to say “bildungsroman” during a podcast interview you realized you didn’t know how to pronounce it. You thought you were writing a novel about how to live. Or how to become the person you want to be despite your circumstances, which is the other thing novels are always about, this is why we have so many books about teens fighting evil empires and adults fighting either fidelity or infidelity, depending on the author’s point of view vis-à-vis marriage.

(You do know how to pronounce vis-à-vis.)

But the thing is that you were always this person regardless of your circumstances, you were writing novels on the back sides of printer paper since you were five. You were going to end up here eventually, scrap paper turning into Lisa Frank notebooks and then the glowing light of the word processor, writing and failing and literally processing until you get to today, your literary fiction debut and a book launch this evening at a local bookstore.

So you can say authoritatively—pun intended—that your book is not autobiography, because someone will ask that tonight at the Q&A.

You shouldn’t have paid $75.24 to print promotional cards asking people to preorder your book, because you barely handed any of them out. You shouldn’t have bought the $250 pack of ISBNs from Bowker because Pronoun gives you an ISBN for free. (You should mention at some point that you also write for Pronoun’s blog The Verbs, but they asked after you published your book with them, so it isn’t a conflict of interest when you recommended Pronoun earlier because you would have recommended them anyway.)

There are things you’ll do differently when you publish The Biographies of Ordinary People: Volume 2: 2004–2016 next year, you’ve made lists, but you’re stuck with your structure and your setting and your characters who might be too polite, and your presumptuous goal to write a two-volume series about how to live, and your title with its en-dash and two colons.

Which is fine, because these are exactly the books you’ve always wanted. You can lose yourself in them—which is a strange phrase to use regarding something you’ve written that was at least 20 percent based on your own childhood, but it’s true. To forget oneself completely is an extraordinary thing. You barely need to add—but you will—that pausing whatever track the mind is currently autoplaying to be fully present and/or fully absorbed is one of the reoccurring themes of how to live. It is also deeply satisfying.

That’s the lesson you’ll end with, the one you didn’t expect: that you can write something that is both from you and separate from you. You’ve written enough sentences that some of them still surprise you. You’ve heard enough reader response to be impressed by both the similarity and the variety. In a few hours you will go to a bookstore and eat cake and answer a few questions and read a few pages and then—you hope—everyone else will read the book on their own.