Please Shut Up About Cronuts

Am I the only one who thinks that the constant drumbeat about “cronuts” is exactly the kind of celebration that happens around a non-story right before something serious and terrible actually occurs? It feels like one more article and we’re due.

Camera Obscura, "Do It Again" (Live)

I love love love Desire Lines, the new Camera Obscura record, but until they put out some kind of promotional video this will have to do. Seriously, get the album — “New Year’s Resolution” is a nearly foolproof cure for a foul mood.

Tick Makes You Like Tofu

If the threats of obesity, E. coli and ass cancer aren’t enough to get you to cut back on your consumption of red meat, maybe you can get yourself bit by this bug, which causes allergic reactions to the stuff. Perhaps responses from “vomiting and abdominal cramps to hives to anaphylaxis” will help you switch over to chicken.

The Andy Rooney Vagina

by Awl Sponsors

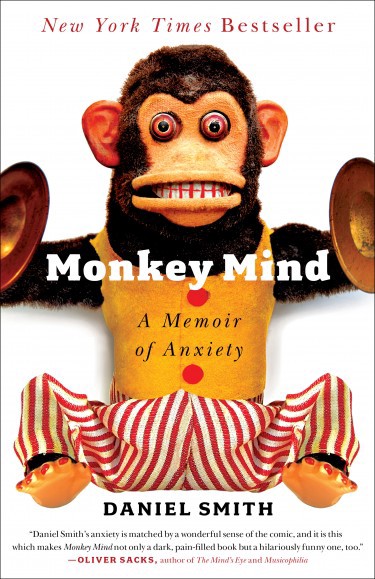

The following is an excerpt from the novel Monkey Mind: A Memoir of Anxiety by Daniel Smith

The story begins with two women, naked, in a living room in upstate New York.

In the living room, the blinds have been drawn. The coffee table, which is stained and littered with ashtrays, empty bottles, and a tall blue bong, has been pushed against the far wall. The couch has been unfurled. It is a cheap couch, with no springs or gears or wooden endoskeleton; its cushions unfold flat onto the floor with a flat slapping sound: thwack. Also on the floor are several clear plastic bags containing dental dams, spermicidal lubricant, and latex gloves. There is everything, it seems to me, but an oxygen tank and a gurney.

I am hunched in an awkward squat behind a woman on all fours, a woman who is blond and overweight. Her buttocks are exposed and her knees are spread wide — “presenting,” they call it in most mammalian species. I am sixteen years old. I have never before seen a vagina up close, an in‑person vagina. My prior experience has been limited to two-dimensional vaginas, usually with creases and binding staples marring the view. To mark the occasion, I would like to shake the vagina’s hand, talk to it for a while. How do you do, vagina? Would you like some herbal tea? But the vagina is businesslike and gruff. An impatient vagina, a waiting vagina. A real bureaucrat of a vagina.

I inch closer on the tips of my toes, knees bent, hands out, fingers splayed — portrait of the writer as a young lecher. The air in the room smells like a combination of a women’s locker room and an off-track betting parlor, all smoke and sweat and scented lotions. My condom, the first I’ve had occasion to wear in anything other than experimental conditions, pinches and dims sensation, so that my penis feels like what I imagine a phantom limb must feel like. The second woman has brown hair done up in curls, round hips, and dark, biscuit-wide nipples. She lies on the couch, waiting. As I proceed, foot by foot, struggling to keep my erection and my balance at the same time, her eyes coax me forward. She is touching herself.

Now the target vagina is only a foot away. Now I feel like a military plane, preparing for in‑air refueling. I feel, also, like a symbol. This is why I am here, ultimately. This is why, when the invitation was extended (“Do you want to stay? I want you to stay”), I accepted, and waited who knows how long in the dark room for them to return. How could I have said no? What I had been offered was every boy’s dream. Two women. The dream.

Through a haze of cannabis and cheap beer, I bolster my courage with this: the dream. What I am about to do is not for myself. It is for my people, my tribe. Dear friends, this is not my achievement.This is your achievement. Your victory. A fulfillment of your desires. Oh poor, suffering, groin-sore boys of the eleventh grade, I hereby dedicate this vagina to —

It is then that the woman coughs. It is a rattling, hacking cough. A cough of nicotine and phlegm. And the vagina, which is connected to the cough’s apparatus by some internal musculature I could not possibly have imagined before thismoment, winks at me. With its wild, bushy, thorny lashes, it winks. My heart flutters. My breathing quickens. I have been winked at by a vagina that looks like Andy Rooney. I feel a tightness in my chest and I think to myself, Oh dear lord, what have I gotten myself into?

I’ll call her Esther. The plump blonde with the unkempt pubic hair and the penchant for teenage boys. The penchant for me. I met her while working at a bookstore in Plainview, New York, at the rough longitudinal and latitudinal center ofLong Island, where I was born and raised. She took an instant liking to me and then she took my virginity, and going on two decades later my mind still hasn’t recovered. Esther set my anxiety off. She was the match that lit the psychic fire. It all starts with Esther…

From Monkey Mind: A Memoir of Anxiety by Daniel Smith

Eyes Expanding

Is this how the human face might look in 102013? Who cares, we’ll all be long dead by then, and even if we weren’t life would still be a grim slog through boredom and despair from which something as unimportant as physical appearance would provide little relief — I mean, sure, why the hell not.

Do You Like Parks? I Also Like Parks

Tonight in NYC: my alternate timeline secret boyfriend Chris Adrian appears at McNally Jackson. Emily Cooke, Sarah Leonard and Elizabeth Gumport talk Mary McCarthy at Word Brooklyn. And tonight’s the City Parks Foundation gala!

'Jurassic Park' Is The Perfect Movie And Explains Everything About The Amazing World Of Science

by Becky Ferreira

On June 11th, 1993, I had my one and only “religious experience.” It began, as is tradition, by staring into the cold hard eye of a raptor. It lasted for 127 minutes, in which I was in a complete state of raptor — sorry, rapture (these words are synonyms to me). I emerged from the movie theatre a changed person. I was like Saint Paul after he fell off his horse and realized, “Holy crap, Jesus is a god-man-thing!” Only my revelation was about dinosaurs, and so is obviously superior.

I had borne witness to the birth of Jurassic Park. I had seen it bite through the fence of public anticipation and burst into the public sphere. And oh, how it bellowed.

I was 8, but I remember how completely earth-shattering this film was right away. My friends and family laughed off my obsession, and chalked it up to childhood dinophilia. Exactly 20 years later, I have signed portraits of the characters framed all over my room, two sets of Jurassic Park toys splayed across my work desk, and all of the dialogue of the movie memorized (and that includes the dinosaurs’ “lines”). So who’s laughing now? Answer: Ian Malcolm, like this.

To say that Jurassic Park is my favorite movie would be like saying Earth is my favorite planet. These are prejudices over which I have no control. I love the movie’s subtle foreshadowing, such as the helicopter landing scene in which Alan Grant — that’s Sam Neil as the paleontologist — has two female seatbelt buckles that won’t connect. But Dr. Grant finds a way (just like the dinosaurs’ lil gametes). I love how Jeff Goldblum makes a tyrannosaur bite look really sexy. I love that when Jurassic Park owner John Hammond is forced to cut the tour short, he whines, “Why didn’t I build in Orlando?” This throwaway line summons magical visions of raptors and Rexes marauding around the Magic Kingdom eating Mickey mascots off of Porta Potties. People on the Jurassic Park theme park ride wouldn’t know what the Fukuiraptor was going on! Makers of Jurassic Park 4, take note: this alternate universe is where you should set your movie.

The minor characters of JP are also beyond phenomenal. For example, Robert Muldoon, the game warden, who has spent months embroiled in crazy staring contests with raptors, and it completely shows. By the time we meet him, he’s too far-gone into this weird rivalry with the “big one” in the pride, like he’s slowly losing his soul to her or something. Indeed, one of the great insights of the movie is that Grant learned more about raptors by studying them as wild animals than Muldoon learned by observing them in captivity. If only Muldoon had overheard Grant’s take-down of that bratty kid at the beginning, he might have understood the most important thing about raptors — they attack from the side. Clever girls.

I’m even an apologist for the movie’s many mistakes. I mean, the Rex footsteps’ produce these monstrous impact tremors, but when she arrives to save the day at the end, she literally materializes out of nowhere. It definitely makes you wonder if she learned to tiptoe. Also, could Dennis Nedry, the park’s computer programmer, have made a more suspicious exit speech? Would that even be possible? Try to sweat and stutter a little more there, guy. And did you notice that the embryo vials for Tyrannosaurus Rex and Stegosaurus were both spelled wrong? I think that screw-up might actually be intentional, a subtle endorsement of Malcolm’s criticism of how Hammond slaps stuff on lunchboxes before he even knows what he has. Indeed, if you watch the movie closely, you can see that Hammond’s charismatic hypocrisy is a running gag. My favorite example is that he claims to be present for every raptor birth as it helps them to, no joke, “trust” him. Cut to: the highest security paddock in the park. Because trust.

But I digress, and on this subject, I always will. So let’s get down to the meat, which is what the dinosaurs would want. What I really love about Jurassic Park is that it is about everything. Or at least, it’s about the everything of science, and that is the most interesting kind of everything.

It’s nominally about dinosaurs, so it’s already starting light years ahead of most movies (what I wouldn’t give for more tyrannosaurs in romantic comedies, for instance). But underneath that layer of awesomeness, it’s a parable about what I call the Triforce of Science. This Triforce is not exactly wisdom, courage, and power, but it’s actually not far off: it’s theory, empiricism, and money. As in Hyrule, each viewpoint brings its own prejudices to the table — and this literally goes down around a table in Jurassic Park. Over plates of Chilean sea bass, the characters lock horns like Triceratops over the very nature of science.

Hold on to your butts.

Ian Malcolm, played with alarming expertise by Jeff Goldblum, represents theorists, the scientific equivalent of prophets. Theorists derive their ideas from real world observation, but they are not beholden to it. Chaos theory, for example, aims to understand complex phenomena like the stock market or the weather. But the field itself is mathematically bound. Chaos theorists aren’t typically out chasing storms to get their data — they’re working with computer models and simulations, abstractions of what actually occurs in nature. This is because theorists take on questions so big and vague that there’s often no hard-and-fast empirical framework for testing them. Accordingly, truth from this perspective is not limited to what can be proven to exist via our sensory experience of the world. This is echoed in the table scene: Malcolm argues that Hammond’s park is an inevitable failure based on probability — just math — which shows that statistically, “life finds a way.”

Across the table, Grant is repping hard empiricism. He’s pegged as a “digger” before he’s even on screen, which is important: unlike Malcolm, Grant has dirt under his nails. Truth is a much harder sell on an empiricist because they base their ideas solely on physical data. Grant, as a paleontologist, relies on the fossil record and biological behavior for his deductions, both of which can be concretely observed in nature. So when Grant says that birds are descended from dinosaurs, it’s because he’s already accrued hard evidence to support that claim. As soon as he’s introduced he’s calmly explaining that his conclusion is self-evident if you actually look at the similarities between raptors and modern-day birds, such as the shape of the pubic bone, and how its vertebrae are filled with avian-like airsacs and hollows.

That’s why Grant’s instinct in the table scene is not to voice an opinion, but to ask a question: “dinosaurs and man, two species separated by 65 million years of evolution, have just been suddenly thrown back in the mix together. How can we possibly have any idea what to expect?” Grant, a true empiricist, doesn’t “want to jump to any conclusions” because he doesn’t have the facts and he hasn’t observed the effects for himself. He won’t budge until he sees some hard evidence. Spoiler alert: he sees some hard evidence.

Finally, we have John Hammond, who represents the commercial side of science. He is an entrepreneur who has selectively chosen what kind of science to support based on its potential return. But there are some serious complicating factors with money and science (…pretty much with money and anything). First of all, patrons tend to expect payback on their investment in research. Despite often having a genuine philanthropic or academic interest in the work they sponsor, as Hammond does, the bottom line for any entrepreneur is an increase in power, be it political, social, religious, or financial. That’s a lot of pressure for a thought system like science, which can’t produce convenient answers all the time, no matter how much money you throw at it.

Patrons aren’t typically scientists themselves, and because of that, they lack insight into the discipline required to solve such gargantuan problems. They don’t, as Malcolm says, “earn the knowledge” for themselves, and thus they don’t take responsibility for it. Hammond’s defense in the table scene perfectly illustrates this shortcoming. Instead of absorbing Malcolm’s point, he accuses him of being a Luddite and asks the painfully idealistic question, “How can we stand in the light of discovery, and not act?” It’s classic political rhetoric, and it talks beyond Malcolm’s critique instead of acknowledging it. Like other powerful men and women who have used doublespeak to get their way, Hammond appears to actually buy into his own words, unintentionally fulfilling Malcolm’s prophesy of avoiding responsibility. It’s kind of a beautiful thing.

This friction within the Triforce reaches its apex around the table, but it’s substantiated throughout the movie. Early on, Malcolm jokes, “God help us, we’re in the hands of engineers,” establishing his discomfort around concrete thinkers. Even his wry joke that he’s always looking for “a future ex-Mrs. Malcolm” suggests that he prefers marriage as a theoretical idea than as a reality. Grant is just the opposite. He only grasps the crux of chaos theory when he discovers hard evidence of it: a dinosaur nest in the wild. And he’s not open to the idea of family life even on a theoretical level because he’s observed overwhelming evidence that children are noisy, messy, expensive, and that babies smell. Having cutie-pies Tim and Lex fall asleep on him twice may sway his prejudices slightly, but tellingly Grant remains a childless bachelor in Jurassic Park III (and the fact that Ellie Sattler’s dumb toddler dicks around with the phone while Grant is about to be eaten by a Spinosaurus probably doesn’t do wonders for his opinion of children).

Meanwhile, despite his grandchildren being hunted by Rexes and raptors, Hammond repeatedly retreats into high-minded rhetoric to eschew responsibility for his guests becoming Lunchables. He snaps at Malcolm when trying to lead Sattler through the Maintenance Shed, defensively saying “I know how to read a schematic!” But he doesn’t know how, not at all, and Malcolm has to forcefully take over to show him how it’s done. This is a beautiful little microcosm of their difference in perspective — Hammond always confidently overestimating himself, Malcolm always able to see the simplest truth in a complex situation. Follow the goddamn pipes.

Hammond’s hubris is most evident in his drippingly self-pitying flea circus speech, in which he rationalizes that the park was “an aim not devoid of merit,” whatever that’s supposed to mean. Sattler is there to hear him out, and set him straight. She is a fantastic character (even more so in the book) and acts as Grant’s sidekick in empiricism throughout the story. She’s actually a little farther ahead than Grant is when it comes to understanding the dangers of the park. Early on, she chides Hammond for putting poisonous plants in the lobby just because they be pretty lil flowahs. But nobody really pays attention to her because they just saw a bunch of raptors demolish a cow, so who gives a crap about some dumb plants? Speaking of crap, Sattler makes her commitment to empiricism unflaggingly clear when she dives elbow-deep into Trike poop (she’s…uh…tenacious), showing that she’s a kinesthetic problem-solver who, like Grant, acquires evidence before she makes conclusions. So she lets Hammond throw his little pity party for a while, but refuses to let him get away with saying “next time, it’ll be flawless” about his death trap of an island by tossing him a very heavy reality check. Luckily, there is plenty of ice cream to console them both.

Now for some caveats: I’m sad to report that our world is not as cut and dried as Jurassic Park and that science in general is far too complex a venture to be boiled down to just three perspectives (especially the non-commercial “big idea” stuff). Also, “theory” is an incredibly slippery word, and I don’t mean to suggest that theorists aren’t attentive to the evidence — they are. But their job is not only to interpret data, but to take speculative steps forward into a bigger picture that may not have direct evidence to support it. I’m definitely generalizing with the term, and I own that, okay nerds? It’s also worth noting that most truly brilliant scientists aren’t only theorists or only empiricists, but a healthy mixture: such is the case with Archimedes, Copernicus, Kepler, Newton, Galileo, Tesla, and Darwin, to name a few all-stars.

All that said, the Triforce of Science is all over the place in science history, because theorists and empiricists do typically rely on patrons of some kind to advance their findings, and in return, the patron enjoys increased personal power. Archimedes relied on King Hiero II of Syracuse to finance his crazy circle drawings. King Hiero II got a great deal out of this too, because Archimedes was an amazing military engineer who helped cement Hiero’s place in history as a legendary defender of his Kingdom. Another good example is the partnership between theorist Johannes Kepler and empiricist Tycho Brahe, who were brought together by their mutual benefactor Rudolph II of Prague. Kepler was a prude and Brahe was utterly debauched, so they really hated each other. But with Rudolph’s money, they managed to create modern astrophysics together nonetheless. Triforce FTW.

While often symbiotic, this trio of perspectives can also quickly become hostile, and that’s when science history becomes pyrotechnic. Hippasus, an empiricist of the 5th Century BCE, was murdered by his theorist patrons after he discovered irrational numbers. Considering Hippasus was as right as the angle on a Pythagorean triangle, this makes his patrons as irrational as the numbers Hippasus pioneered. Conflict has also repeatedly risen between the patrons and the scientists, perhaps most notoriously in the case of Galileo. Up until the publication of Dialogue Concerning the Two Chief World Systems, Galileo had Pope Urban VIII’s friendship and support. But his vehement defense of Copernican cosmology incited the Dope to bring charges of heresy against Galileo, which landed him under house arrest for the last nine years of his life. Boy, does Galileo hate being right all the time.

I don’t expect Jurassic Park 4 to dwell on these themes the way the original did. None of the other sequels have, though they are both well worth watching. The Lost World is very stupid, but I don’t know how anyone can resist a T-Rex rampage through San Diego or the film’s adorable mother-son bonding session, in which the Rexes eat the villain (sooo cute! Seriously!). Jurassic Park III is one of the most underrated comedies of all time, in which, no joke, a Spinosaurus eats a cell phone so you always know whether it’s around by listening for the freaking Nokia ring tone. Brilliant.

But even though the sequels aren’t about the everything of science, every Jurassic Park film pays homage to the Triforce in one meaningful way: the dinosaurs themselves. The artist Miranda Dressler has an amazing piece called “Jurassic Park’d,” in which each character is drawn as a dinosaur. She drew Malcolm as a brachiosaur, an animal whose unrivaled far-sightedness perfectly represents theory. Grant is a raptor, an empirical animal that thrives on testing and interpreting hard evidence. And Hammond is the Rex. The blunt force instrument. The catalyst of all the action. The beast that can’t see what is plainly in front of him.

Happy 20th anniversary, Jurassic Park. And thank you for sparing no expense.

Becky Ferreira is a comedy nerd and actually is a dinosaur. “Electric Rex” is by Kyle McCoy. “Jurassic Park’d” is by Miranda Dressler.

New York City, June 9, 2013

★★★★ The odds on the long-term bet had turned bleak, at nearly the last minute, but now here was the payoff after all: The sky over the apartment building’s deck was clear, all clear, devoid of anything that might even slightly resemble a threat. Decorations could be taped down to dry paving blocks, paper streamers wrapped around dry railings. The wind sent bunches of newly inflated balloons, weighted with mere rolls of masking tape, retreating down the hallway; the balloons would need to taken outside and tied down one by one. Some of the children — with their short time horizons, their indifference to the perils of how things could have been — saw fit to complain aloud that they were awfully hot under all that sun. But there was the shade and air conditioning of the playroom for them to retreat into. In the playroom, it was rumored, entropy and animal spirits were rampant. Out on the deck, though, the sunshine was baking the children into spells of near tractability. Ice melted and soaked through the bottoms of the paper cups of popcorn. A gust yanked a balloon loose, yet kept it low and horizontal long enough to be run down and recaptured. The birthday boy was flushed and a little glazed over. The first match blew out. The second match blew out. The third. The fourth. More. Barely scorched matchsticks were piling up. The wick on the numeral 6 candle caught briefly and went out again. Indoors, with a lighter, it caught for real. On the way back out the doorway, out it went. Again the lighter, sheltered by hands and cardboard — the cupcake and flame thrust quickly at the birthday boy — makeawishmakeawish — and the breath of childhood finally prevailed. Two hours of battering by the wind had visibly shrunk the balloons, and their ribbons were so twisted and braided that they seemed to have been fused into a single solid rope. With a little work, and a pull from the top, it was still possible to extricate a parting gift for each child, a short-lived but still buoyant keepsake.

Mushrooms Might Make You Suck Less

You know those days where you wake up and before your feet hit the floor your head is already heavy with dread, the walk to the bathroom is like swimming through warm, flavorless jello and brushing your teeth is a massive undertaking during which your mind is a place full of painful memories and pointed reminders that you’re not likely to do any better in the future? Those mornings where you avoid looking at other people on your way to work because you can’t bear to see or be seen? When you’re forced to expend what little mental acuity you have left keeping your thoughts away from the things that might make you cry? And you feel like all you’ve done lately is screw things up, make people sad and apologize for being such a drag? Maybe on those days you should take some mushrooms. It could hardly make life worse, right?

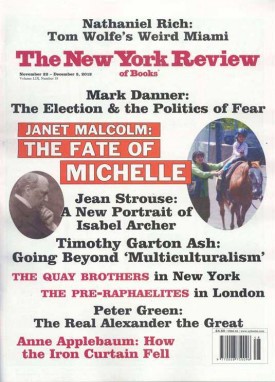

'New York Review Of Books': Founded By Canny Capitalist Opportunists

“What happened was this: there was a great newspaper strike in New York in the autumn of 1962, and my friend Jason Epstein, an editor at Random House, had the inspiration — which he imparted to the poet Robert Lowell and his wife Elizabeth Hardwick — that this was the one time in history that you could start a book review without a penny, since all the publishing houses had no place to advertise their new books. No New York Times Book Review. Jason and I knew that, if we started a plausible book review, then all the publishers would simply have to take a page. They had to show their authors that they were publishing books.”

— Here’s an interview with Robert Silvers.