We Endorse The Hooker Dude

The incredibly wealthy Eliot Spitzer, who lives in his dad’s building at 985 Fifth Avenue, up the street from his dad’s building at 800 Fifth Avenue, was one of the very few people hollering about the out-of-control Wall Street corporate culture before the recession. As pushy as he was, he didn’t do enough. As A.G., he sued the stock exchange’s Dick Grasso for his golden-parachute money-grabbing. He nearly took down AIG back in 2005, before AIG nearly took down New York City. He did not, and he should have. Before that, he crusaded against fake anti-abortion “family crisis center” facilities. Good! Eventually for some reason he ran for governor, which was a stupid choice, unless he’d run on a New York City secessionist platform, which would have been awesome. Some day! Then all that stuff happened. Five years passed.

His opponent Scott Stringer is a decent dude, but he’s a fairly nice guy. Eliot Spitzer is not. We are either going to end up with a screamy asshole mayor, like Chris Quinn or (unlikely) Anthony Weiner, or we are going to end up with a decent, hard-working, non-asshole mayor, like Bill de Blasio or (unlikely) that other guy, the one who ran last time, whose name I can never remember because he’s SO QUIET, WHY DOES HE NEVER SAY ANYTHING MEMORABLE. In either event, having a mouthy, obnoxious, pushy jerk for Comptroller is going to be important, either to push back against the screamer or to help out in being the strong arm for the wussier mayor.

A combo of nice-guy Stringer and imperious Quinn would be a disaster; she’d stomp on him. But also, a combo of two polite and kinda wimpy dudes would be a disaster. We have a long proud history of asshole mayors. It’s just that sometimes we get the wrong kind of asshole (like a Giuliani, or, possibly, a Quinn).

New York City needs a dick to stand up for us downtown. New York City needs a dick like Eliot Spitzer.

Camera Obscura in Central Park, Franklin Park Reading Night and a Special Warhol Screening at MoMA

AAAAAAHH IT’S VERY WARM. Warning! Half of today’s events happen outside, what are we thinking? That includes the Franklin Park Reading Series tonight, and a screening of Taylor Mead’s Ass in MoMA’s garden, and also Camera Obscura in Central Park!

Also this happened to the cover of the New York Post.

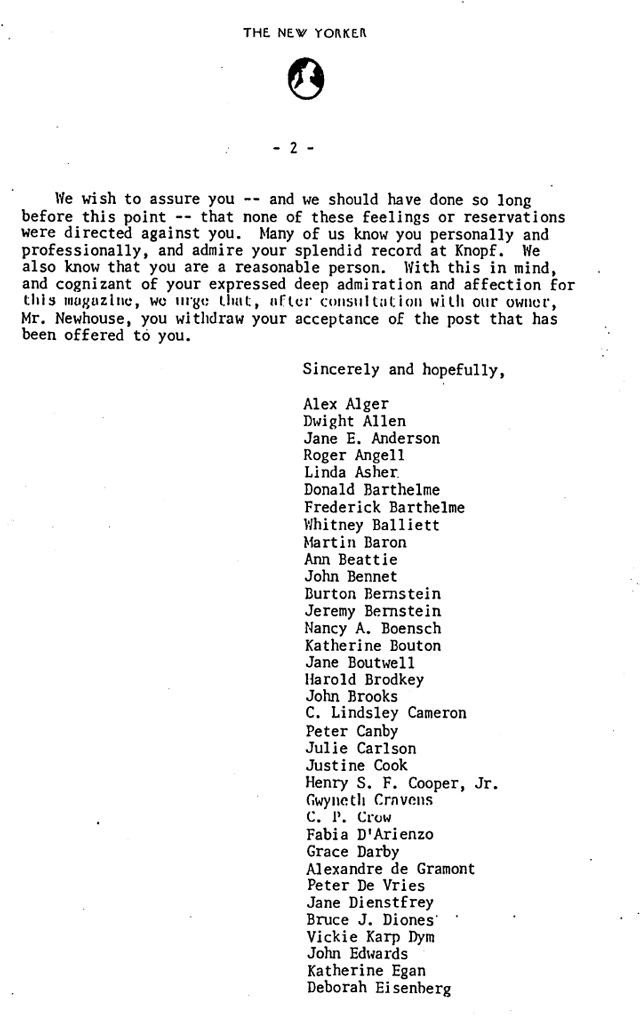

The Letter

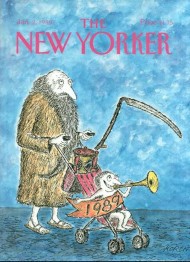

William Shawn began work at The New Yorker in 1933, was appointed managing editor in 1939 and, quite shortly after the death of founding editor Harold Ross, became the magazine’s editor in 1951.

In 1985, 34 years later, Shawn was still the editor, but Peter Fleischmann, the son of founding partner Raoul Fleischmann, owned only 25% of shares in The New Yorker. Paine Webber owned the next largest share, and the Newhouse family’s Advance Publications already owned around 17% of the publication. Advance wanted, and got, the rest, for a price something like 20 times current revenues, according to the Times.

The employees, however, were not happy with their new owner. “We were not asked for our approval, and we did not give our approval,” Shawn told the staff at the time of the sale.

The idea of a third editor for The New Yorker had been discussed prior to the sale. Shawn turned 78 in 1985; this was not an abstract concern. Shawn and much of his staff believed that Advance chairman Samuel “Si” Irving Newhouse, Jr. had given the beloved Shawn a say in the naming of the magazine’s next editor.

The pervasive assumption was that the successor would be picked from within. Charles McGrath, Shawn’s deputy editor, was Shawn’s top candidate, at least most recently. “Newhouse initially seemed to go along with the plan,” reported New York. In any event, according to Ben Yagoda’s About Town, Newhouse had drawn up an “Agreement and Plan of Merger,” which stated that Advance would consult “a group of staff members” before picking an editor.

If you are familiar with the takeover promises extracted by the Bancrofts from Rupert Murdoch prior to his purchase of The Wall Street Journal, then you know how much weight such agreements carry. “No such group was ever formed,” wrote Yagoda. Newhouse appointed Alfred A. Knopf editor Robert Gottlieb editor of The New Yorker, and informed Shawn on January 12, 1987. “Si didn’t give a shit, and why should he?” Daniel Menaker told me recently. He was Fiction editor at the time. “He owned the magazine!”

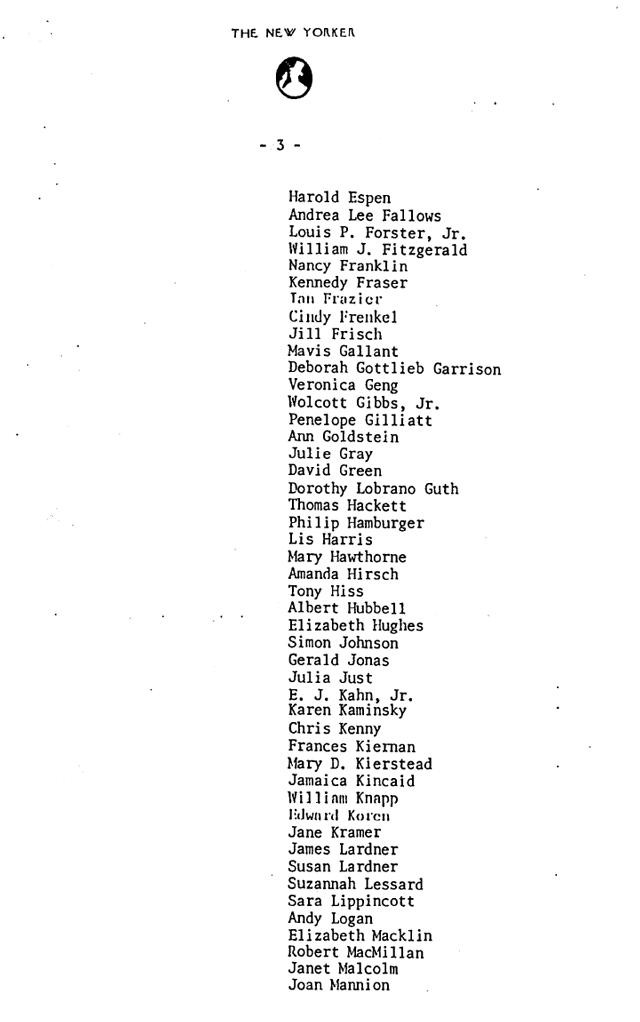

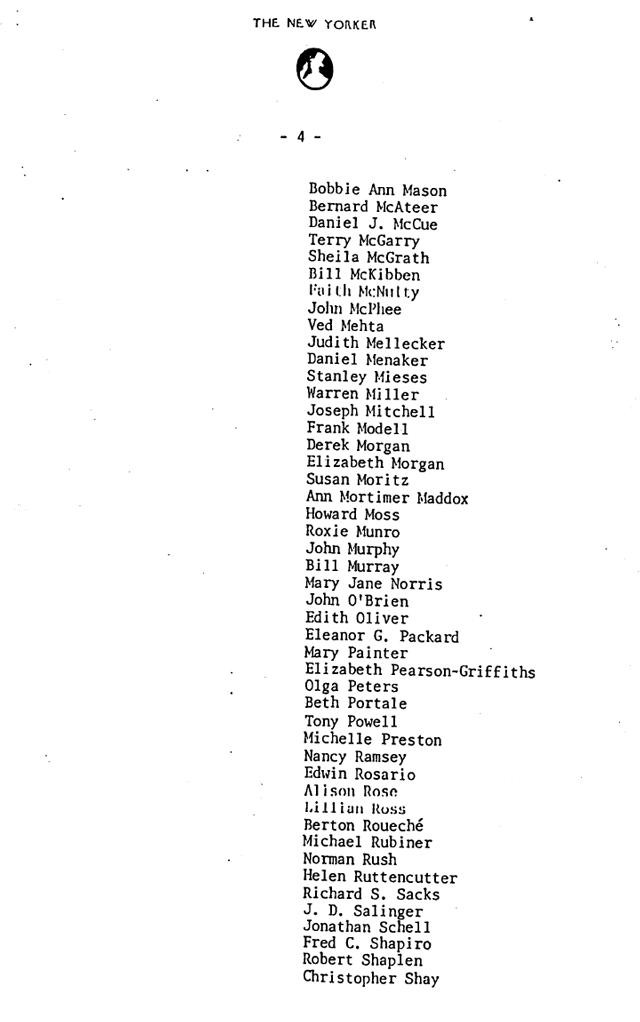

Gottlieb’s appointment enraged the staff, who were again not asked for their approval. It didn’t much matter that Gottlieb’s publishing career was the stuff of well-deserved legend; he’d edited Joseph Heller, Michael Crichton, Robert Caro, John Gardner, and so on. The reaction was, well, fairly New Yorker-ish. A very proper letter (“scrutinized and corrected by the magazine’s fact checkers and proofreaders,” wrote the Times) was sent to Gottlieb, beseeching him to decline the job. Containing four pages of signatures, the letter made clear that the staff’s anger was not so much with Gottlieb himself (“Many of us know you personally and professionally, and admire your splendid record at Knopf”) as the “sadness and outrage over the manner in which a new editor has been imposed upon us.” Many staffers wrote to the new boss (“sort of off the record,” as a former editor put it) and explained that to him.

This was not the act of a fringe contingent. The letter — which, until now, has never been published in its entirety — is signed by 154 staffers, including J.D. Salinger, Calvin Trillin, John McPhee, Jamaica Kincaid, Saul Steinberg and Janet Malcolm. There are a few notable abstentions, including John Updike and Charles McGrath, who would soon be named Gottlieb’s deputy. At the bottom, it reads “cc: S. I. Newhouse.”

This petulant, useless act triggered quite a bit of press coverage, both national — 4490 words in the Los Angeles Times (“BREACH OF TRADITION; NEW YORKER SHAKE-UP IS TALK OF TOWN”), 3,590 words in the Chicago Tribune (“TROUBLE IN WRITERS’ PARADISE; A TORRENT OF WORDS OVER THE NEW YORKER”) — and local. The New York Times’ Edwin McDowell filed three stories in as many days. The magazine hadn’t drawn such attention since 1965, when Tom Wolfe depicted Shawn in the New York Herald Tribune’s Sunday supplement New York magazine as a “museum curator, the mummifier, the preserver-in-amber, the smiling embalmer … for Harold Ross’s New Yorker.”

Roger Angell — at ninety, the only New Yorker staffer to have worked for every editor, including Ross — said that, to some degree, the media reaction to Wolfe’s lacerating two-part story (“Tiny Mummies! The True Story of the Ruler of 43rd Street’s Land of the Walking Dead!” and “Lost in the Whichy Thicket,” respectively) ought to have been expected: “We’d asked for it, or Shawn had asked for it, because we had become so private and whispering and closed away.”

The scrutiny that greeted the magazine after word of the letter leaked to the Times should have been expected, too. “It was the strangest thing that ever happened in the history of the magazine,” said Angell, who, like most of his colleagues, seemed mildly humiliated by his role in its composition; he was “sort of the recording secretary.” That day, a half-dozen staffers had stood around him, dictating. “It’s still strange to send a letter to somebody saying ‘don’t come.’ It’s like something happened in a nursery! It’s so strange, so child-like, the whole thing in retrospect. It was heartfelt! We didn’t want Shawn to go — nobody wanted Shawn to go, I don’t think.” With hindsight, Angell said, “Shawn had stayed too long.”

Menaker, a 26-year veteran of the magazine, described his decision to sign the letter this way: “It wasn’t so much objecting to Bob as it was a foolishly altruistic notion that Newhouse should have done what he said he would do.”

Nearly a decade ago, Gottlieb told his Paris Review interlocutor, The New Yorker’s Larissa MacFarquhar, that the letter was no big deal. “I knew that the same thing would have happened to anyone. I didn’t even read the names of the people who signed the letter, many of whom were good friends of mine.” Gottlieb’s colleagues, including his dear friends McGrath and Angell — the latter of whom laughed at the notion — do not believe this. According to McGrath, one signatory was more painful than the rest: Janet Malcolm, whose The Journalist and the Murderer would run in Gottlieb’s New Yorker over two weeks in March, 1989. “Of all the names,” said McGrath, “I think that one really wounded him because Janet is a very close friend.” (Mr. Gottlieb declined to be interviewed on the record for this story.)

I wrote to Malcolm and told her this. I asked one question: Why did you sign the letter? “Dear Mr. Green,” she replied, “I sent your letter to Bob Gottlieb for his comment, and the correspondence that followed may be helpful to you in the writing of your article.” She continued, helpfully:

Bob wrote:

“Was I hurt by your signing The Letter? Do I remember? I really only remember that the letter barely affected me, except for the hilarity of their sending over the wrong one.”

I wrote back:

“I never knew anything about a wrong letter being sent over. Fascinating! I, too, recall, that the letter barely affected you. That was the idea. It was an empty gesture understood by all or at least by all with any sense to be just that. “

I’d like to add two things to my comment: One is that the gesture was made to make the beleaguered and embittered Mr. Shawn feel better, not to make Bob feel bad. The second is that it was a pleasure and privilege to write for the magazine when Bob was its editor.

Best wishes,

Janet Malcolm

Bill McKibben and Jonathan Schell quit the magazine in solidarity with Shawn. Their departure was contemporaneously framed as the exit of “the conscience of the magazine,” as staff writer Mark Singer put it. McGrath vigorously dismissed the idea: “That’s the Shawn mythology. He kind of created that thing himself; I think he believed it. He was very bitter. He felt betrayed. He thought everybody should have quit and, in fact, only two people did…. It’s just not true, and Bob is, in his own way, a highly moral and ethical person.”

I reached McKibben recently; he was in Australia, doing work for the climate change group 350, of which he is the president. Shawn, he emailed, “was the greatest editor in American letters, and a friend, and I’m prone to getting annoyed with the rich and powerful.”

Lillian Ross left, too, for presumably different reasons, only to return once Gottlieb had been deposed. “She was probably the greatest of the Gottlieb badmouthers,” said McGrath. “She was convinced, and Shawn was convinced, that Bob had just vulgarized the magazine beyond recognition. It just wasn’t true. You just had to pick up the magazine. I remember having lunch with Shawn after the changeover. He told me, ‘Of course, I never read it anymore. But on page 321…’”

The staff otherwise remained remarkably static. Gottlieb, who seems to possess the marvelous quality of not being at all vengeful, fired no one.

The dominant view of Gottlieb’s editorship, which lasted fewer than six years, is sunny. “I think most people at the magazine found Bob easier to get along with, and easier to work with, than the remote and mysterious William Shawn,” McGrath said. “It is true that some of the writers found Bob’s manner difficult to adjust to after Shawn, but basically it was a cheerful place. It was a lot of fun to work there. There was a sense of common purpose, in a way more than there was in the Shawn era.”

Menaker agrees with this view — “emphatically” — but believes it’s beside the point; Gottlieb should never have been appointed. “I don’t think he was the right choice for the job,” he said, and asked me Gottlieb’s age at the time of the appointment. Nearly fifty-six, I said. “Too far along. It’s odd that Newhouse replaced a superannuated editor with a verging-on-superannuated editor. That’s too old. It’s increasingly difficult to pay attention to minutiae and politicking.” (It’s worth mentioning, I think, that Menaker is critical of Shawn, too. He told New York his old boss was “one of the most manipulative people I’ve ever known — far and away.”)

“When you do a fucking weekly magazine, I mean, the need for attention — I don’t know how Shawn did it, and I think he also, obviously, didn’t do it for the last five or 10 years,” Menaker said. “I remember seeing Bob’s proofs on stories, or even non-fiction that I was editing, and they would start out being pretty attentive. And then by the fourth or fifth galley, they would sort of subside, and his comments would subside. And he’s not the most patient person in the world, anyway, but I think the descent into micro-detail — of the kind that The New Yorker has been sort of famous for — was a descent that he didn’t want to or couldn’t take.” This, he said, was owed to Gottlieb’s age: “Very smart, very alert, seemingly ageless, but I now know through personal history of being a pretty attentive person myself that it’s very hard to maintain the illusion that the concert records column is of any importance and needs to be scrutinized after a certain point in your life.”

Gottlieb had relatively narrow interests; put crudely, his passions were books and ballet. “Bob had no interest in politics, and it just bored him,” McGrath said. In this way, he said, Gottlieb was not unlike his predecessor. “In a funny way, he and Shawn were the least worldly. There were great swaths of life that Bob was simply uninterested in — sports, certain kinds of pop culture. Just about anything that takes place outdoors.”

Angell agreed with this, but believed it was good for the magazine: “We were less political. Shawn believed that some current events might be the end of civilization as we knew it, and if The New Yorker failed, that would be the end of civilization as we knew it. The air of our own significance was there and I think Bob lowered that feeling significantly, and much to our benefit.”

The work for which Gottlieb was most contemporaneously criticized — Jane Stern’s “Buddies” (September 1987) and Robert Stone’s “Helping” (June 1987) — holds up quite well. The first was derided as kitsch, the latter as profane. Stern’s story is particularly scorned. It was, admittedly, out of place at a magazine that was still largely Shawn’s, but today Stern’s chronicle of the Scottish Terrier convention is just delightfully weird:

Stone’s contribution was his first appearance in the magazine. Twenty-six years later it doesn’t seem so scandalous for a National Book Award winner to say fuck every now and then.

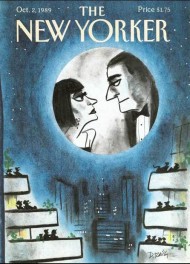

There was also unambiguously great work: pretty much everything by Alma Guillermoprieto and Julian Barnes; John Hersey’s coverage of the seventh world congress of International Physicians for the Prevention of Nuclear War; and particularly Ian Frazier’s “Great Plains,” a brilliant exploration of the American West published across three issues in 1989.

The footprint of magazine editors — particularly New Yorker editors — is the writers they leave behind. This is true, certainly, of the much-derided Tina Brown, who strengthened the front and back of “the book” with Anthony Lane, Jeffrey Toobin, Alex Ross, Seymour Hersh, Jane Mayer. It’s true, too, of Gottlieb, albeit in a quieter way. Barnes wrote the wonderful “Letter from London”; the ferociously talented Guillermoprieto sent dispatches from Mexico and South America; and Susan Orlean made her first appearance in Talk of the Town in 1987 — a gorgeous, delicate piece about clothing-folders.

Orlean was an early Gottlieb-era hire. “She came in off the street,” said McGrath, her Talk of the Town editor (though, she noted, Gottlieb was often her second reader). “She came into my office and, in the space of a twenty-minute conversation, she had about a hundred ideas for stories, and about eighty of them were good.”

Orlean laughed about this. “By the standards of The New Yorker I was being brought in off the street. I had a book contract; I was writing for Rolling Stone and The Boston Globe, so that’s hilarious. That’s so classic of The New Yorker to feel that if you weren’t at The New Yorker you were essentially homeless and living hand-to-mouth on crap.”

“When I got there the mood was not very nice,” she said. Orlean was unusual among New Yorker writers, most of whom, she said, had spent their careers at the magazine and hadn’t written for other publications. “It’s a little bit like, I wasn’t a virgin, and more typically people came to The New Yorker as virgins. They came into their adulthood there.” The place was cliquey, she said, but that has since dissipated, in no small part because Gottlieb brought in so many writers who “weren’t born in the manger.” At this point, “that aristocratic, inbred feel — that if you weren’t there from birth you didn’t deserve to be there — has really dissolved.”

Orlean had worked with good editors before, but she found The New Yorker a different animal. “I’d never been in a situation where the quality of the work was all that mattered. The dispensing of all the stupid conventions of magazine writing that I was very familiar with was just totally different. You didn’t do the kind of clichéd nut graf. To this day, there’s a very typical sort of way you go about a magazine piece or a profile — you just didn’t do that at The New Yorker.

“Another convention that got thrown by the wayside is, I would spend all this time working on these flourishes for my closing and feel very proud of myself for having that great summary paragraph at the end, and closing out with an overview of the way everything works. And the first story I turned in, Chip basically chopped the last paragraph off. Well, Chip told me, you already ended the piece. It was completely liberating.”

“Folding,” which came from one of Orlean’s original pitches, was about the Fifth Avenue Benetton clothing store. It ran in the May 25, 1987 edition. Orlean would write dozens of pieces during the next five years.

But Gottlieb’s real strength was the fiction. “There was a real spike in new contributors when Bob came,” said Menaker. “I think that has to do with the fact that, as a book publisher, he had very strong literary tastes but also kind of popular, demotic taste. Under Shawn, Fiction had become implicative, restrained and somewhat wan, but Bob liked louder voices.” (To this day, Gottlieb’s friends are astonished by how much he reads. Not long ago, Gottlieb read the entire Fifty Shades of Grey trilogy.) Among the writers who made their first Fiction appearance in The New Yorker on his watch: Richard Ford (March, 1987), Salman Rushdie (June, 1987), Michael Chabon (September, 1987), William Gaddis (October, 1987), Ann Cummins (April, 1988), Ann Packer (June, 1988), Michael Cunningham (July, 1988), Lorrie Moore (July, 1989), Margaret Atwood (March, 1990), Haruki Murakami (September, 1990), Allegra Goodman (April, 1991), Abraham Verghese (October, 1991), Antonya Nelson (December, 1991), Martin Amis (June, 1992).

George Saunders doesn’t make that list, but only on a technicality. By the summer of 1992, when he sent in “Offloading for Mrs. Schwartz,” he’d already submitted four “pretty weird” stories and it was only his stubborn refusal to make small changes that kept one out of the magazine. In 1984, while he was working as a groundsman in an Amarillo, Texas apartment complex, Saunders was asked if he would change the ending of “A Lack of Order in the Floating Object Room.”

“I was a callow youth,” Saunders said. “Of course, when I sent it to Northwest Review, I changed the ending.”

He was in Watertown, New York in August of 1992 when he got the acceptance call for “Offloading for Mrs. Schwartz,” purchased by Gottlieb. “I was working for an engineering company, so we had to go up to Fort Drum and do environmental sampling out in the swamp. The answer was coming any day now, so every day I’d work like fourteen hours and I’d go back to the Microtel and ask the desk clerk if there’d been a message. And one night he said ‘Yeah! Here’s it is’ and it was The New Yorker saying ‘We’re taking it.’”

The editing with Menaker took one brutal month. “Dan had a way of forcing reconsideration of every phrase, every punctuation mark, every emotion. It was just The New Yorker way. Of course, at the time it was incredibly painful…. They seemed to be anti-contraction in those days. There was quite a bit of talk about ‘house style,’ which, you know, I’d never really heard of before. Also a lot of talk about swearing, fuck especially. It wasn’t like you couldn’t do it, but it seemed like they tried to minimize the number of contractions in the story and minimize the use of the f-word.”

The story was ready for publication when Gottlieb was fired. Saunders said his “gut feeling” was that there “was a lot of negotiating with some of the traditionally-minded people at the magazine. A sense of, ‘What is this new magazine going to tolerate?’ Because the story is kind of a sci-fi romp, you know.” Ultimately, the story appeared in Tina Brown’s inaugural issue, was read by millions and caught the eye of Esther Newberg, who became Saunders’ agent. Things have worked out okay.

In December, 1991, David Remnick, The Washington Post’s Moscow correspondent of three years, was watching everything — Communism, the regime, the Soviet empire — come apart: “The Soviet Union’s last day on Earth was Christmas night.” He’d covered the story for the Post quite closely — sometimes filing two or three stories a day — but “there are some things you couldn’t even get in the newspaper.” Remnick decided to write a piece about the last days of Gorbachev.

He queried The New Yorker — via telex or phone call, he’s not sure — and was told they wouldn’t assign it, but were he to write it, “we’d happy to look at it.” Which he did, quickly, and filed it on a Friday morning in January of 1992. That night, Remnick, home with his wife and baby, got a call from Gottlieb. He had read the piece, the editor told Remnick, and said they’d like to publish it soon.

There was one note: “I think the first 800 words are bilge. Get rid of them. Get faster to where the story is.” (Once, under orders from Gottlieb, Chaim Potok struck 300 pages from The Chosen.) After it was handed off to Remnick’s editor, Pat Crow, the piece was put through the wringer. “I had never been through editing like that or fact-checking like that,” said Remnick. “Letter from Moscow” ran March 23, 1992.

Eventually Crow introduced Remnick to Gottlieb. “In walked this guy wearing what could only be described as the clothing that would have been worn by a kind of Columbia undergraduate in the fifties. Kind of a plaid, shortsleeve shirt and khakis that Target might have been ashamed to sell,” Remnick said. Gottlieb sat down on the floor in Crow’s office, looked up at the map, trying to decide which far-flung locale Remnick ought to go to next. “I was so exhausted from where I’d been; I was hoping he’d look at Italy or France but his eyes kept going towards places like Mongolia,” Remnick said.

“And he talked talked talked talked talked, and he gave me a tour of his office, which at that time was dominated not by the handbag collection — of which there were certainly plenty of them — but by his sandpaintings.” (Gottlieb had a famously large women’s handbag collection.) “Lots of clowns and Elvis,” Remnick said. “He’d covered every inch of the wall. And on the door were clippings from The National Enquirer.”

Remnick spent the rest of 1992 at a fellowship at the Council on Foreign Relations, where he wrote Lenin’s Tomb. In the summer he got a call from Tina Brown, for whom, he said, “I’d written a grand total of one story at Vanity Fair, and had never met her in my life, asking me to lunch.” The entire lunch, he recalled, Brown “talked about The New Yorker and I had no idea why. But I found out over the summer. She clearly knew this was happening.”

Gottlieb’s firing, on June 30, took the editor and his staff by surprise. “I thought I’d become an old fart at The New Yorker,” Martha Kaplan, Gottlieb’s managing editor, who had come with him from Knopf, told me. She quit soon after. “They didn’t know how good they had it,” she said.

Brown demanded the summer to think about her plans for the magazine. Gottlieb gamely stayed on for three months; Brown returned “from a week’s vacation at a Wyoming dude ranch” and installed herself in her own temporary office.

For Gottlieb, being fired — like Malcolm’s signature to the letter — had a personal aspect to it. He and Newhouse were friends. “I think Bob felt betrayed,” said McGrath. “But that’s how Newhouse has historically always worked. You never know — till the assassin comes in the dead of night and knocks on the door.” Newhouse, in a statement released to the press, said Gottlieb had resigned over ‘’conceptual differences.”

The staff was stunned, and again angry with Newhouse, who they believed had once again gone back on his word. This time, however, the staff kept its mouth shut. There was one exception: Garrison Keillor, who’d flourished under Gottlieb, told the Chicago Sun-Times that he didn’t know Brown but Vanity Fair was “a trash pit.”

“People had learned their lesson,” said McGrath. “When Tina came, they just held their breath and waited to see what happened.”

“In retrospect,” said McGrath, “I think he didn’t change enough. Even at the time, there were writers who we were urging him to dump, and he wouldn’t do it, and it’s partly because he had this great faith in his own abilities as an editor, and in the editorial process of the magazine itself. Bob was this great optimist. He kind of thought he could fix anything, and any writer could be redeemed.”

Another theory about Gottlieb’s tenure concerns the letter. “I’ve often wondered whether the letter, and the whole scene when he came in, was not such a strange event that it may have altered what kind of editor he was,” said Angell. “He might have been more radical, more useful even. I don’t know how he would have done differently, without that initial reception. Maybe he was careful after that.”

Menaker — who has a memoir coming out later this year, a portion of which is about his time at The New Yorker — told me Angell was not alone in this belief. “A number of people have told me that, even though Bob’s response to the letter was brief, concise and, in a way conciliatory but also firm, nevertheless he was very affected by that letter. The thought is, that he might have been more adventurous, more mold-breaking, had it not been for that letter.”

“What that more adventurous stuff might have been, I don’t know,” he said.

“In retrospect, we all should have not signed,” said Angell.

I don’t think it matters. That Gottlieb consistently put out a very good (if perhaps not great) magazine, in a medium with which he didn’t have much experience, amid intermittent rumors he’d be fired, is no small thing. The big picture is important.

Orlean believes the magazine owes Gottlieb, her fellow outsider in a deeply insular place, a debt of gratitude. “I’m not sure The New Yorker would be here today if Bob hadn’t been there to provide an interim government,” she said. “Had you dropped Tina Brown in after Shawn, the whole place would have exploded. You would have had pretty much everyone leave and it would have been a mess.”

“I give him enormous credit,” said Remnick, who — in a lovely turnabout — now publishes Gottlieb. “William Shawn was an astonishing editor. But the way it all ended was dramatic, depleting, sad for everybody and destabilizing. And to walk into a magazine where the staff has written you a letter saying ‘Don’t come,’ and to do the job that needed to be done, is pretty astonishing.”

Elon Green is a contributing editor to Longform.

New York City, July 2, 2013

★ Beauty was the herald of misery. After a morning and midday of rumpled gray, the afternoon clouds broke open, revealing dazzling white highlights and blue above — and allowing unfettered sun to mash down on the wet unmoving air like a giant hand flattening a wad of hot putty. The sidewalk led through a miasma of dog-piss fumes, vegetal rot, steaming mulch, and the hovering molecules from a lone smoker’s cigarette. The train air conditioning, sharp and overdone enough to cause flinching the day before, was now nothing but a relief. The late-day air downtown was like a badly vented laundry room with all the dryers going at once. Later, in the dark, a thin rain fell, too feeble even to make a person wet.

Is It Better To Be Fat Or Cool?

“If Weight Gain Follows Smoking Cessation, Is it Worth it?”

— This is one of those “you will have to decide on your own” things, I guess.

Sure, Leave

“Ghosting — aka the Irish goodbye, the French exit, and any number of other vaguely ethnophobic terms — refers to leaving a social gathering without saying your farewells. One moment you’re at the bar, or the house party, or the Sunday morning wedding brunch. The next moment you’re gone. In the manner of a ghost. ‘Where’d he go?’ your friends might wonder. But — and this is key — they probably won’t even notice that you’ve left.”

— How do you make your exit from parties

? I generally tell the person whom the gathering is in celebration of not to leave without making sure they say goodbye to me first, and then sneak away, which makes them feel like they somehow eschewed their responsibility and gets me off the hook. But there are plenty of ways of cutting out. Also, I am worried that Slate has, like, one or two topics left, probably about where to hide boogers after you pick your nose in the office and how to fart in an elevator, and then they will have to shut down because they’ll be all out. I guess they’ve had a good run.

Photo by Catalin Petolea, via Shutterstock

15 Things To Do This 4th Of July Holiday Week

There are some things to do the rest of this week, but not so many! That is because this is when America does nothing, in celebration of being American. I’m good with that. Enjoy your meat and/or meat substitute! Have a drink or a fake drink for us!

Simpler Times Misremembered

“The TV Watch column on Thursday, about a ‘Today’ show appearance by Paula Deen, who lost her cooking shows after she admitted using racist language, misstated part of a comment by Bill Clinton in a reference to other public figures accused of wrongdoing. In 1998, responding to accusations that he had had an affair with Monica Lewinsky, Mr. Clinton said, ‘I did not have sexual relations with that woman,’ not ‘I did not have sex with that woman.’”

— God, remember 1998?

Tracey Emin Is 50

Happy birthday to Tracey Karima Emin. She may have just turned 50, but she’s still outrageous! I mean, probably. It’s not like that’s the kind of thing you turn on and off for effect, right? (Whatever, she’s great. Remember this? No one will ever be able to be that normal again. Or want to.)

Ask Polly: How Do I Stop Meeting Arrogant, Mentally Ill Pricks?

Hi Polly,

I finally have been hired for my dream internship, in my field, and utilizing my educational background. In a large international megapolis. But….

After years of dating, I am writing to you for some guidance on how to approach dating abroad/in a totally new place. I recently broke up with the last of a slew of asshole, arrogant, mentally ill prick boyfriends. One of whom raped me, resulting in years of difficult, but productive therapy. I feel like I am in a good place and want to date someone who is professional, reasonable and you know — cool. Not a meanie.

I am just really worried about ways to meet dudes that are safe, healthy and not professionally compromising. Do you have any suggestions for ways to meet people that do not involve 1. Dating people at work or people who know your coworkers (because we all know how that affects careers and work environments), 2. Dating friends of relatives (last asshole was cousin’s best friend), 3. Or alcohol/drunken mistake situations (rapist was bartender).

Or, should I just focus on becoming a superstar international lawyer and let romance be second to my career?

Your truly,

Moving, single and confused

Dear MSAC,

Do you mean you’re looking for ways to meet dudes that are safe, healthy and not professionally compromising (i.e. don’t meet them by doing acid and then bungee jumping, or by striking up conversations at the free STD clinic, or by skipping work to hang-glide drunk)? Or do you mean you’re looking for ways to meet dudes who are safe, healthy and not professionally compromising (i.e. friendly, fit men in a different professional field)?

Let’s assume the latter! So: You’ve dated a string of asshole-ish, arrogant, mentally ill pricks. Are you traditionally attracted to men with supernatural levels of confidence? Assholes, the arrogant, the mentally ill, pricks: they often have an irrational surplus of confidence in common.

Here’s my tough question of the day, though: Can you tolerate regular men? Men who are stable and/or reasonably established in their lives or their careers, but who possibly appear, at the outset, slightly boring? Men who don’t necessarily display their wit and charm under pressure? (The ability to do this is highly overrated in our society. Studies show that sneaky wit and charm in men tend to have better long-term payback for their partners, and it’s less often accompanied by dickwaddery and dipshititude.)

First of all, though, let’s just admit that the world is filled with semi-unattractive, overconfident men who believe themselves to be well nigh irresistible. Somehow the mere fact of their overconfidence attracts a herd of adoring females who are fifteen to twenty times better looking than they are — which only makes these guys even MORE overconfident. Don’t start arguing with me about this, people. You know it’s true.

So first of all, I feel strongly that we need to reverse this equation. Aggressive, swaggertastic but average-looking women (like me!) should always land the ultra-hot man-babes.

We deserve them, because we are smart and entertaining and seriously obnoxious, which turns into excitement and adventure over the long haul (in women, anyway). Instead, though, bland little Margarets and Marys in grosgrain headbands who can talk for 20 minutes straight about their favorite lasagna recipe land the really hot guys, because ladies like that seem more relaxing and sexually attractive. (What makes them so sexy? Is it those little sighs of resignation they make in bed that really turn men on?) Betty Draper, minus the cigarettes and the rifle, that’s what these ladies are! They’re Olivia Newton John — the one with cardigan sweater, not the one in the shiny black asspants! Is it fair or just that almost all of the hot men out there are awarded to these wilty little Strawberry Shortcakes? Fuck no, it is not.

Meanwhile, our semi-unattractive and self-congratulatory male peers are swimming in sexy ladies. They’re very relaxed about the prospect of losing you, because they know there are fifty to sixty more just like you to choose from the second they give you the boot.

And anyway, you date one of these guys and it’s all peachy at first, all adorable and romantic and special. But don’t be deceived! You know that thing that Ferris Buehler does, when his dad is tucking him into his bed for the day because he’s “sick”? That little growl, the coy way he blinks his big brown eyes and giggles? Kind of a Zach Braff maneuver? If you meet a guy who does that sort of thing with his parents, run the other way! You know the type. That guy is spectacularly good at charming the pants off everybody, but then he turns into a major dick overnight. He pulls you in with total focus, then wakes up one day and informs you that he’s over your whole dumb girl thing, big time. (Yes, women do this, too, obviously. Right now we’re not talking about them! Stop interrupting, you!)

You won’t know it until it happens! But there will be clues. Maybe he’ll slip up. He’ll interrupt his talk about how “humbled” he is over this or that stupid thing, and instead he’ll say something about his “fans”! He’ll say, “I know that you, my fans, want me to be me, because I am precious and amazing just the way I am.” And you’ll be like, “What? Did you just call ME your ‘fans’?” and you’ll also be like, “Hold on. That’s my line! I’m the one who matters in this picture, dummy!” Or maybe he’ll roll his eyes at some woman with her back fat showing, and when you set him straight about that, he’ll refuse to acknowledge that today’s fashions are basically designed to display back fat at all costs, and unless you’re doing Tae Bo during your lunch hour (instead of stuffing onion rings into your face, which is your birthright), you have to dress like fucking Archie Bunker to hide your (adorable, delicious, smallish) love handles.

My point is, it’s time to ignore the arrogant pricks (whom you might have more in common with — if you’re me, anyway) and start paying attention to the low-key, tentative but secretly hilarious and super sexy guys (who are way, way better than you — again, if you’re me).

Also? Don’t get drunk and then decide who to date. In fact, while you’re dating around, don’t get drunk at all. It’s a liability. Keep your wits about you, keep your eyes peeled, open your heart, and get out into the world and see who’s there. Where are the good, safe, healthy ones? I have no fucking idea where they are. All I know is, you can’t see them if what you really want is to be glamoured by some cocksure bozo. Examine your priorities closely, and then set out into the world and do your motherfucking thing! (Without the tequila, though.)

Good luck!

Polly

Dear Polly,

Three months ago, I quit my job and moved four hours’ drive away to live with my boyfriend, a relationship of about six months that felt especially special given that it had been the longest and deepest I’d had (other than my boyfriend from my study abroad, which, admittedly, was a five-year-er — though starting when I was 15).

Anyway, I knew it was quite a risk. We’re both immensely independent and unashamedly introverted people, and a domestic partnership is not something I really imagined for myself. But I loved and trusted him, and felt in my gut that even if the relationship fell apart, we’d remain friends. We’re both the type that “takes a long time to get to know/warm up to,” but he’s been nothing but giving. I wanted to take a few months while still young enough to move “for a boy” and see how it went.

You probably can where this is going.

But it’s not a shitshow. I’m making progress in redefining my career, enjoying being a cat step-mom, learning to cook and living comfortably while getting along well with my best friend, as we always have.

We just don’t have sex.

The quality of the sex went down steeply very shortly after I moved in, but, being naive and all “we’ll figure it out as we go along,” I figured this was part of domestic partnership — and the immense love I felt daily made me feel valued and warm. I struggled with feeling down about my job prospects for the first few weeks here with the kind of Eeyore fatalism of Those in Our Mid-Twenties, but my boyfriend, my partner, was supportive and kind. I thought perhaps a lack of bedroom antics may be because his view of me shifted, as my self-view did, into someone rather powerless and just around too often. It wasn’t entirely pretty, but I learned to be patient. When I tried initiating sex, this is what he told me: No, but we will soon. Be patient.

Then I got a job, and then another, to make things work. And I felt more on track to being a healthy, attractive person again. Meanwhile, though, it’s been a good six weeks since we’ve even attempted sex — this is included in the three months we’ve lived together, mind. Maybe that’s normal, but I’m 24 and he’s 30 and we’ve been dating less than a year. Does bed-death really happen that fast?

Two weeks ago, when I tried to talk about it in a reasonable way, he admitted that he didn’t believe he’d ever want to have sex with me again. He said this had happened to him in relationships before, but that he figured I would have left by the time I “figured out” that his sex drive had dropped to zero. I handled it calmly for a day, and told him he could talk more about it when he was ready. When he refused to talk to me several days later, I broke up with him. A day after that, we got into a massive fight that ended with us hugging and crying and vowing to try to make it work. Eventually, I told him that I don’t understand it — that he loves me but just doesn’t have any sexual desire — but that I’d like him to see a doctor. I did not explicitly say it to him, but I think he’s depressed.

So now I’ve decided to be patient, and we live as happy partners. Is me wanting sex too much to ask? I don’t think so, but when I try to think deeply and rationally about the situation, I really do think he wants to put the breakup on pause while I look for my own place — that we’re platonic roommates who kiss, and that he doesn’t want to get his groove back.

That’s what kills me. I’d stay with him if he just tried. He’s encouraged me to date other people, which I have no problem with intellectually, but it’s just not what I want, which is him. I love him for the person he is, and I’d build a life with him if it’s what I felt he really wanted, and I knew was good for me. I’m hurt, offended, betrayed slightly, though — and devastated that he won’t do something to figure out why he has no interest in sex.

Have I just not given it enough time? Am I allowed to really break ties with my best friend for refusing to fuck me?

Confused

Dear Confused,

Yes, I would break up with him. He sounds great, and I know this sucks, but this has nothing to do with you. He didn’t say he’d work on it, or that he was wildly attracted to you but was depressed, or that this has never happened before. He said this has happened before, and that HE PROBABLY WON’T EVER WANT TO HAVE SEX WITH YOU AGAIN.

I mean, hot damn! The fact that he can say that and not immediately put a therapist and a psychiatrist and a doctor on speed dial, the fact that he’s saying “Oh well, no sex drive yet again, but no, I’m not going to talk to anyone about it,” the fact that he treats the whole picture like a foregone conclusion? That’s really all you need to know. He’s pretty sure he never wants to fuck you again, and he’s not going to talk about it, with you or anyone else.

Again, this has nothing to do with you. And it’s not just about sex. Even though everything else is great, it won’t be great over the long-term, even if you DID resign yourself to some kind of platonic relationship. This problem is related to other problems. Problems he doesn’t want to solve. Problems he doesn’t want to talk about.

Now, I recognize that there are people out there who define themselves as asexual, who would dislike me calling this refusal to have sex a “problem.” They’d prefer that I call it a “choice.” If I were advising your boyfriend, and if he were actively choosing to live an asexual life, that would be different. For your purposes, though, this is a big fucking problem.

He is not over 50. He did not just have prostate surgery. He did not tell you there was a problem with your relationship, and that’s why this is happening. He has a problem that he refuses to fix. He won’t fix it for you or anyone else.

So you have to move out and start over. You’re too young to be locked into something that’s not going to serve you, with someone who doesn’t want to face the music (or, at the very least, define what he wants and doesn’t want). You cannot waste another minute in this situation. You can’t compromise yourself like that — it’s bad for your mental health, your life, your career, your sense of yourself.

Honestly, I know that you’re in a really, really tough place, but you should feel grateful that at least the situation isn’t more ambiguous. People get locked into shitty relationships for so many bad reasons, but because those reasons are foggy and mysterious, they stay way too long and waste too many years of their lives. You don’t have that problem! Your relationship is terminal.

Find a new place. Get your own cat. Move forward. You will be sad for a while. But you must repeat this to yourself: “This has nothing to do with me.” He knows that, and you know it. Resist the urge to take it personally. Resist, resist, resist. If he misses you when you’re gone and vows to look at his problems directly and tackle them in a few months, you can cross that bridge then. But right now, you can’t wait around for him to decide. He should’ve warned you before you moved in together. He is broken and doesn’t want to be fixed. Maybe someone out there is just aching to find a great asexual guy. That’s not you.

Polly

Heather Havrilesky (aka Polly Esther) is The Awl’s existential advice columnist. She’s also a regular contributor to The New York Times Magazine, and is the author of the memoir Disaster Preparedness (Riverhead 2011). She blogs here about scratchy pants, personality disorders, and aged cheeses. Scary man photo by Arun Kamaraj. Scary clouds photo by Neil Alejandro.