Waxahatchee, "Never Been Wrong"

What gets better?

Whatever bad things are going to happen over the rest of the year — and oh my God, so many bad things are going to happen; we’re going to look back at this time and say, “Hahaha, can you believe we thought those were bad things?” — at the very least there is a new Waxahatchee record coming out next month, and it is terrific. Here’s another track from it. It will probably be the only good thing you get today, so enjoy.

New York City, June 4, 2017

★★ A woman walking east held a hand up in front of her sunglasses against the light. There was a soft ticking of ductwork coming to life inside the church. A merchant shook out a bag of shiny things under the canopy of a street-fair booth, with a sound that carried for dozens of yards. To the usual disappointment of the fair, once it opened, there was added the graying out of the sun, as the gorgeous morning faded to something lightless and uninviting. Sometimes it rained; sometimes it didn’t. A bubbly scum of algae floated on the fountain, giving off a stink in the humid air.

The Sword, "Doom Side of the Moon"

Duuuuuuuude.

Dude, you wanna toke some grass and see some shit? Hang on, you know that band from Austin called The Sword, right? So scope this out — their guitar dude, Kyle made some wild ass shit. But first you gotta rip one with me cuz this puppy’s gonna make yer ass fly. Check it: motherfucker made a stoner metal version of Dark Side of the Moon, man. I know right isn’t that focked up? My man, you gotta see the vid, it’s tight. But first we gotta get like kite-flying-into-a-nebula-and-bursting-into-interstellar-confetti high.

Alright, dude, you ready? Fullscreen that shit. Prepare to achieve maximum stokage:

Fuuuuuuck. Did you see those fuckin’ visuals, man? How the fuck did they do that? You think it’s like Photoshop or Paint or some shit? Did you see that fuckin’ rabbit? Is that not some of the Bob Gnarliest shit you’ve ever seen, dude? The breakdown with the organ? Holy balls man I almost stroked out for a sec. If it wasn’t so chill I might have.

The only bummer is the rest of the record isn’t out ’til August, man. I know, it fockin’ suuuucks. But dude, they’re playing the whole thing live in Austin, with a fuckin’ laser light show, man. Holy shit, we should fuckin’ go. We can take the VW, I don’t even give a fuck if it’s overheating, man. We can make grilled cheese on the engine block, dude, it’ll be cozy as fuck.

In all seriousness: Doom Side of the Moon is a beautiful and uncomplicated idea that will be independently released by the band on August 4th. John Dziuban does not smoke weed and he is no longer a musician. Metal Minutiae is an occasional column on the decline of rock music.

Where You Came From

An American family, a racist letter, and feeling unwelcome in brown skin.

“This is something he always said would happen. And I always told him it wouldn’t, that we weren’t in Texas,” said Sarah Hernandez in her kitchen in Longmont, Colorado this past April.

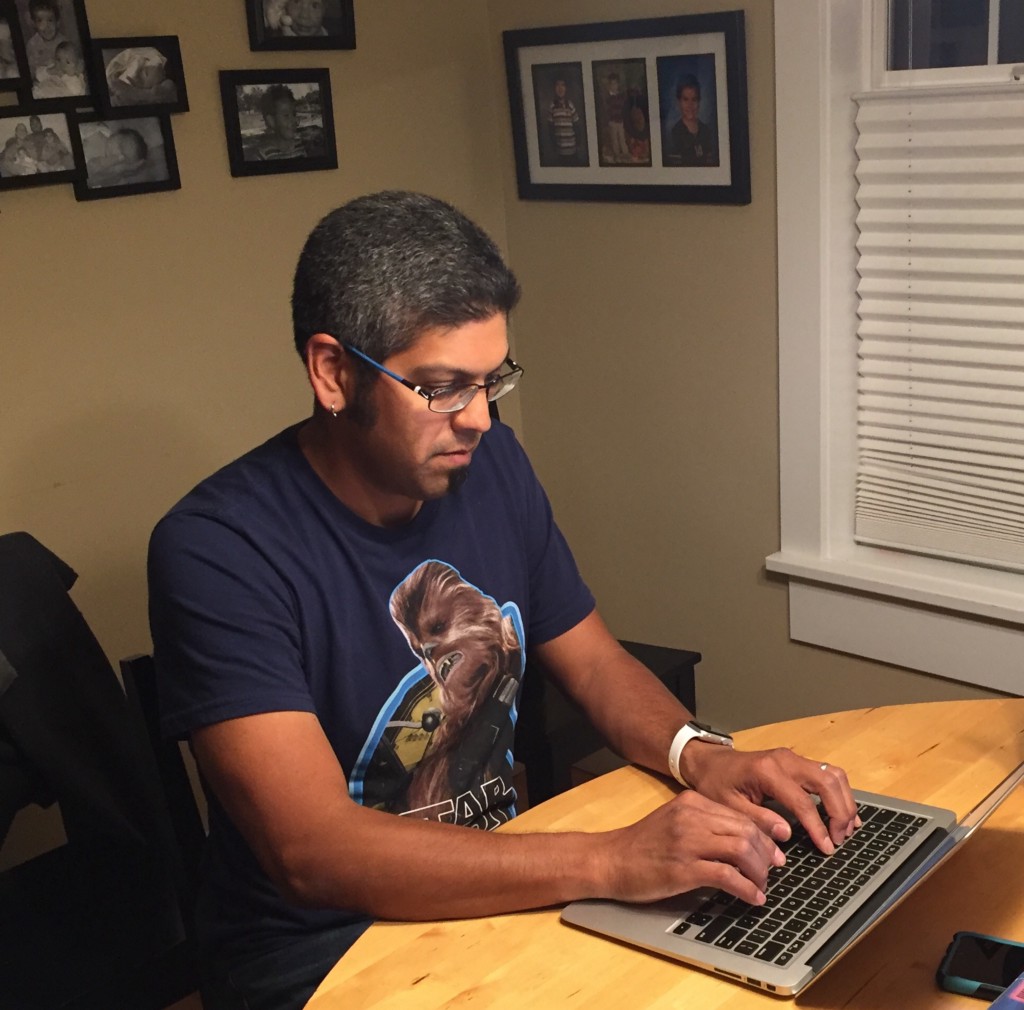

The previous Sunday, April 23, 2017, Sarah and her husband Daniel had been in Louisville, Kentucky for the VEX robotics world championship. Daniel is a computer science teacher at Westview Middle School in Longmont, Colorado, where he’s the coach of the robotics team. He’s also a Star Wars fan, who signs his emails: Danny “Vader” Hernandez.

Danny and Sarah were in high spirits when they returned Wednesday evening; their team placed 4th. While she was going through the mail, Sarah came to a handwritten envelope with no return address. “I opened it, and I pulled out a half sheet. And I read it once, and I got cold. And then I read it again, and then I called him over…and then we sat down, and then we took some breaths, and I said, ‘I need my phone. We’re going to call the non-emergency [police line].’ And we did.”

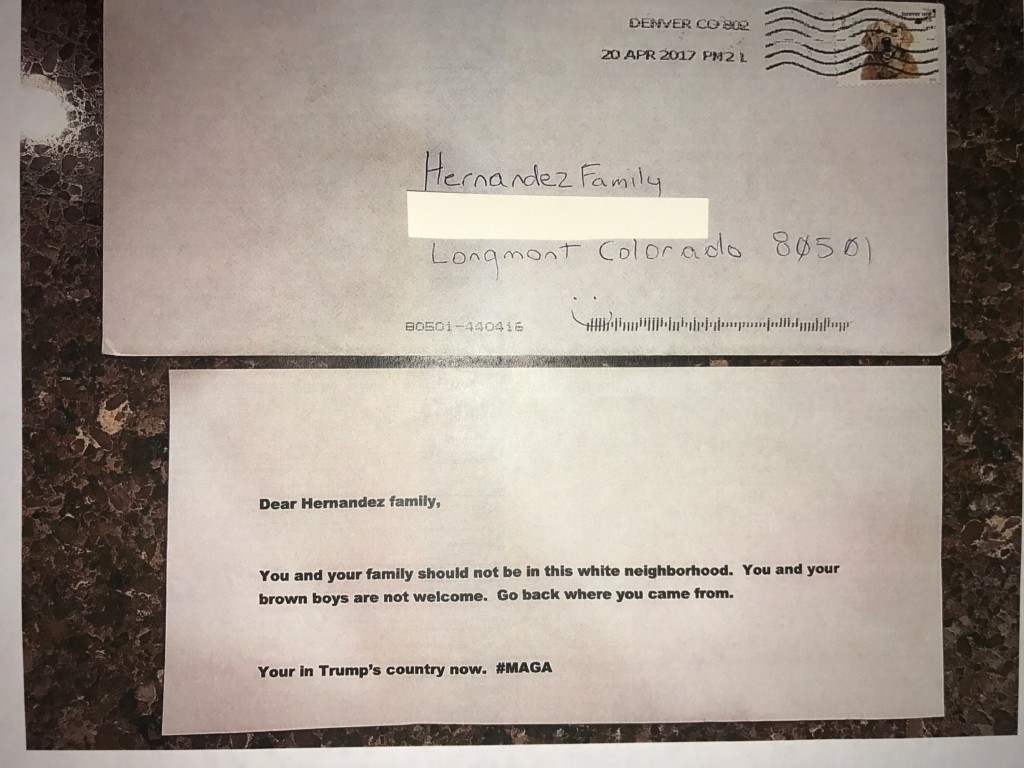

Dear Hernandez family,

You and your family should not be in this white neighborhood. You and your brown boys are not welcome. Go back where you came from.

Your in Trump’s country now. #MAGA

Danny and Sarah met in 1997 at Baylor University, where Sarah, an athlete from California played on the school’s soccer team. Despite their affinity for each other, Danny immediately warned her that she would be the target of intolerance simply because she was dating someone who wasn’t also white. “He was like, ‘Are you sure?’” Sarah remembered. Danny shrugged in agreement. “We’d be a mixed-race [couple],” he said. For Sarah, the concern had never crossed her mind. To her, Danny looked like another southern California surfer boy. But Waco, Texas wasn’t Malibu.

For Sarah, this letter is further proof that Boulder County, Colorado isn’t either. This incident far surpassed the looks and the taunts they got at Baylor, and the rude comments they’ve heard since. For Sarah, it was a shock considering where they live — the Old Town neighborhood of Longmont, where yards sport signs that urge people to vote against fracking, and others that say “No matter where you are from, we’re glad you’re our neighbor” in three different languages. “Maybe it was a false sense of openness and open-mindedness. Maybe it’s the circle we run in. It’s a fairly liberal circle,” she offered. Then she added: “It’s a bubble.”

A reasonable first question would be, who sent the letter? It could have been anyone, a middle-aged racist; a younger, racist millennial. A man, perhaps. Or a woman. When the Hernandez family shared it on Facebook, many people questioned if it was even real. The Hernandezes told me they’re not surprised that people immediately doubt the story. Danny told me he’s been tailed multiple times at his local Bed Bath & Beyond by employees who believe he’s there to shoplift. Sarah said when she goes out with her kids, some people react with surprise or doubt that she’s their mother. “I’ve been asked if [their son] Luke is from Guatemala. ‘Oh, did you adopt him in Guatemala?’”

The Hernandezes are an all-American family. Danny, now 40, was born in Dallas, Texas. Sarah, now 39, was born in southern California. They have three boys, all born in Colorado. Sarah, who’s also a teacher, is white. Danny is, as the letter says: brown. But he was born and raised in Dallas. “I’m not going back to Dallas,” he quipped, and then he and Sarah delivered the punchline in unison, “it’s too fuckin’ hot.”

Danny’s mother, who is of Spanish and Mexican descent, was also born in the States, and his father is an immigrant from Mexico. “He came here legally with all his paperwork and everything, joined the Army. He did his stint with the U.S. Army and all of that, and then all the kids came along,” Danny said.

Danny’s father was a tailor and shoe repairman. The business was a success, so just before Danny was born, his parents relocated from a rough area in south Dallas to the more affluent but far less diverse Farmers Branch in the north Dallas metroplex. In elementary school, he was only of one of three non-white students, the other two were Asian and black. If he had hoped he would be less of an outsider when he entered middle school, he was wrong. Dallas was bussing students in from all over the city, so the middle school Danny went to was far more racially diverse, and significantly larger than his elementary school. But instead of finding companions in other Mexican-American students, they rejected him for being “too white.”

But he was too brown for the white students. They called him an enchilada, a burrito, a wetback. Danny’s way of dealing was to take their comments literally and turn it back on them. When they would call him an enchilada, he’d ask them if they meant the kind with cheese. When they’d call him a wetback and tell him to swim back where he came from, he’d tell them, “I’m pretty sure you’re not Native American. So your swim back to France or England is a much longer swim than mine. So you might want to get started.” It wasn’t until high school that things began to change. “It took a student who was not dark-skinned and who was popular to shut it down,” Danny explained. “It didn’t matter what I said,” Danny concluded. “It mattered what other people said.”

Danny developed into a skilled athlete, and the popular students came to his defense. People wanted to be his friend, and girls began approaching him. But he’d endured more than a decade of racist treatment from most of his schoolmates. “It’s like, ‘No. Now you want to be my friend? No. We’ve been together since grade school, and you’ve either contributed directly or indirectly’,” he told me. Even now, he opens Facebook to find friend requests from people he went to school with in Dallas. He doesn’t accept them. “That wound is deep,” he told me. “We’re not friends.”

Maybe it wasn’t a grown man or woman who sent the letter. Maybe it was a kid.

I met Daniel in Longmont, Colorado in 2013 when I was invited to join a neighborhood beer club. All the members live in or very near a tiny area on the west side of Longmont, Colorado known as “Old Town.” It’s about six long blocks north-south, and about ten short blocks east-west. Despite being such a small neighborhood, the beer club has about 30 members, and we’re all pretty close in age. It’s really just a bunch of thirty- and fortysomething dads with young kids and old houses that need something fixed. Sarah’s right: it’s a bit of a bubble.

Tom Vela is also in our beer club. He’s in his thirties, and he’s got two kids. His wife Liz teaches kindergarten at the same elementary school as Sarah. Liz, like Sarah, is white. Tom is half-Mexican, half-German. (Though, like Danny, he’s American-born.) Tom identifies as Mexican. He does, however, look white.

Tom’s experience has hardly been parallel to Danny’s. Where Danny’s family ran a successful business, and Danny excelled academically and athletically throughout all of his years of school, Tom’s family struggled. His father was a Vietnam vet and a firefighter, and then he left the family when Tom was eight. “We lost everything. We lost our house. We started moving place to place. For us to be able to make it, my brother and I started stealing food and those kinds of things… We felt abandoned. There was a lot of hate, and a lot of anger. We started getting into trouble.”

Money was tight, and at times non-existent. “I was in fourth grade, I think. I went behind one of the porn stores, and they threw out all their magazines. And I jumped in the dumpster, and I took all the ones I could remove, and I sold them at school. I just needed money… It was hard being really poor.” He shoplifted, too, but only necessities. “It was always food… I wanted bread…and tortillas are a very easy thing to slide right in front of your belly and walk out. And it’s a good, filling food.” Soon, Tom took up a more lucrative trade. “You make a lot more money selling drugs.”

It wasn’t drug dealing that got him into trouble, but fighting. After one particularly bad incident — a physical altercation with a teacher and police officer — he was arrested and expelled from school for half a year. This earned him a six-month stay in a juvenile detention facility. But there was one good thing: Tom took advantage of the counseling. “I was on the wrong path. I didn’t want to struggle my whole life. I definitely didn’t want to go back to a place like that, which was basically a jail or detention center… And I was headed down that path…either dead or in jail…” When he was released, he made up his schoolwork and tests, and managed to graduate on time. He continued to sell drugs out of necessity, but stopped as soon he was able, managing to never get caught for it.

Tom applied to college and was accepted. He enrolled in Colorado Mesa University, where he earned his BA, double-majoring in economics and finance. He then went on to Denver University, where he earned his master’s degree in organizational leadership. Tom’s now the vice treasurer of the Parent Teacher Association, chairman of Rocky Mountain PBS, and he’s a highly successful consultant. How many of the chances people took on Tom were because he looked white?

“I don’t know. It’s so hard for me to know. But I will say that I’m in an industry that is predominantly white male, and it doesn’t have a lot of Latinos. That says a lot. It’s a very small amount. Why is that? I don’t know. Could [my appearance] possibly play a factor, yes. A lot of people who get to know me see me as a white person. It may have provided me privileges. Definitely a likelihood,” Tom offered.

While Danny was being called a wetback, Tom had an entirely opposite experience growing up. He told me about the time he was playing with a new friend, a white kid. The boy assumed Tom was a safe person to be racist with. “All of a sudden, he just says to me, ‘Damn, I just can’t stand fucking Mexicans.’ And I looked at him, I’m like, ‘What?’ And he’s like, ‘Yeah, I fucking hate Mexicans.’ I mean, we’re like 9 years old, 10 years old. And I was like, ‘Why?!’ Like I didn’t even understand. ‘Oh they’re disgusting.’ And that’s when I said, ‘Well, I’m fucking Mexican,’ and we fought.”

The day after the November presidential election, a Latino woman — one of Danny’s fellow teachers — was waiting in line in a local donut shop when a white woman, also in line, said to her, “I hope your bags are packed because you’re not welcome here anymore.”

“I hope your bags are packed because you’re not welcome here anymore.”

“I think we are seeing more incidents,” said Stan Garnett, the Boulder County District Attorney for the State of Colorado. “A lot of these, as distasteful as they are, are not criminal. We’ve had several hateful letters mailed to the Jewish Community Center, to some other religious groups. And I think there has been more of that since the election.” I asked whether there were more of these incidents since Trump was elected, or if it was only just our awareness of them that’s increased. “My view is that there have been more, and there also have been more reported,” he said.

I asked Garnett why. “My view is that it’s a direct outgrowth of the nature of the rhetoric surrounding the 2016 election. My view is the United States is a country where racism and xenophobia have always at least simmered below the surface. I think the 2016 election unleashed some of that publicly,” he said.

The Hernandez family reported the letter to the local police, even though whoever sent the letter did not necessarily commit a crime. “Basically the First Amendment protects almost any public communication short of one that advocates immediate violence or rises to the level of harassment…It may be distasteful. But it’s not illegal.” And in this case, Garnett said he doesn’t think anyone’s committed a crime, and added, “if it’s not illegal, and this doesn’t appear to be, law enforcement should not be spending efforts trying to figure out who the person is.”

I asked Longmont Police Commander, Joel Post, why they were trying to identify the sender of the letter if it wasn’t a crime. He explained it was in case the Hernandez family experienced any more harassment. If there were any threats, they would view the Hernandez letter as a potential clue or evidence. In other words, it’s preemptive police work.

And just because someone sends a letter anonymously, doesn’t mean they have the right to stay that way. “[They] don’t have a right to anonymity. You have rights of privilege in the United States if you talk to a lawyer, talk to a priest, talk to a therapist. But you don’t have a right to be anonymous for this type of thing.” And as for “this type of thing,” Garnett didn’t mince his words. “There’s something incredibly chickenshit about somebody who states something, particularly something hateful, and is too scared to sign it.”

As of this time, Commander Post said he has no word on how far along they are in their investigation into who sent the letter.

I interviewed Danny and Sarah in their kitchen, where the island was overflowing with flowers sent to them by friends and neighbors. Whenever I’ve seen Danny in the last four years, he’s always joking about something, and there’s always enthusiasm in his voice, whether he’s talking about his kids, robotics, baseball, beer, or Star Wars. But as I sat across from him and Sarah, Danny was a mix of stoic and angry. I was surprised by how little he said. When he did speak, his words were witheringly angry. Gesturing to the flowers all of his friends had sent them over the previous few days, he said, “Now I just have a bunch of flowers to water.”

Danny is not only angry about what happened, but I also see that he’s exhausted. At one point, he tells me “The terms used in this note, that’s not a first for me.”

For him, it seems, the damage is already done. But for their kids, it’s not. They’ve been growing up in the same protective, progressive bubble Sarah and Danny have been in since they moved to Longmont. They go to the elementary school in the same neighborhood where they live, and where their mom teaches. The other children don’t know them as “brown boys.” They know them as neighborhood kids whose mom teaches at the school they go to. In fact, they’ve been so shielded from discrimination, Sarah told me that they’re not even all that aware of their race, or how it differs from anyone else’s. “Benny and Andy, it’s kind of the same thing — they’re not aware,” Sarah explained, then added, “Luke once said he thought he’s white. We were like, ‘buddy, you’re both.’” So now their main concern is this: how will they be treated in school by kids who they haven’t grown up down the street from?

Danny is widely known as a favorite teacher, a coach, and a fun dad. Sarah is known as one of the most cherished teachers, too. She plays soccer and enjoys craft beer. They are at every picnic, barbecue, party in the neighborhood. They are power couple of suburban, middle-class goodness. A non-profit called Showing Up For Racial Justice shared the incident on their social media accounts, while a Longmont Bike Night was held in honor of the Hernandez family. When the local paper, the Longmont Times-Call, covered it, they called the Hernandezes a “Historic Westside family.” But how much does that really matter? That the Hernandezes are a “good” or “upstanding” family has no bearing on how disgusting the letter is.

What their status as a family has afforded them, though, is the support and confidence to be able to speak out about what they’ve experienced. “I don’t know how isolated [this incident] is,” Stan Garnett told me. “The experience of being undocumented in the United States for most people is a very, very lonely experience. When you talk to members of the undocumented community, the thing you hear more than anything else is how isolated and lonely they feel. When there is an incident like this, it has a real impact on the sense of security and well-being of the undocumented community.” He continued: “This family who experienced this and felt confident to reach out is great. There’s a lot of people who experience things like this who are afraid to tell anyone about it.”

There is a gap between what actually happens and what we think happens. The gap that reveals itself when something like this happens in, of all places, Boulder County, known as much for its progressive politics as its craft breweries. When Danny posted the letter on Facebook, people left comments, aghast, expressing their disbelief that such an awful thing could have ever happened. It’s that disbelief that Danny thinks that’s part of the problem. About everyone who’s been so blindsided, Danny asked rhetorically, and with a good dose of frustration: “How can you not know this can happen?” Then his voice softened, and he said, “But if you’ve never had to live it or experience it or be around it, I guess in some ways, how would you know it’s happening?”

Summer in the Sky

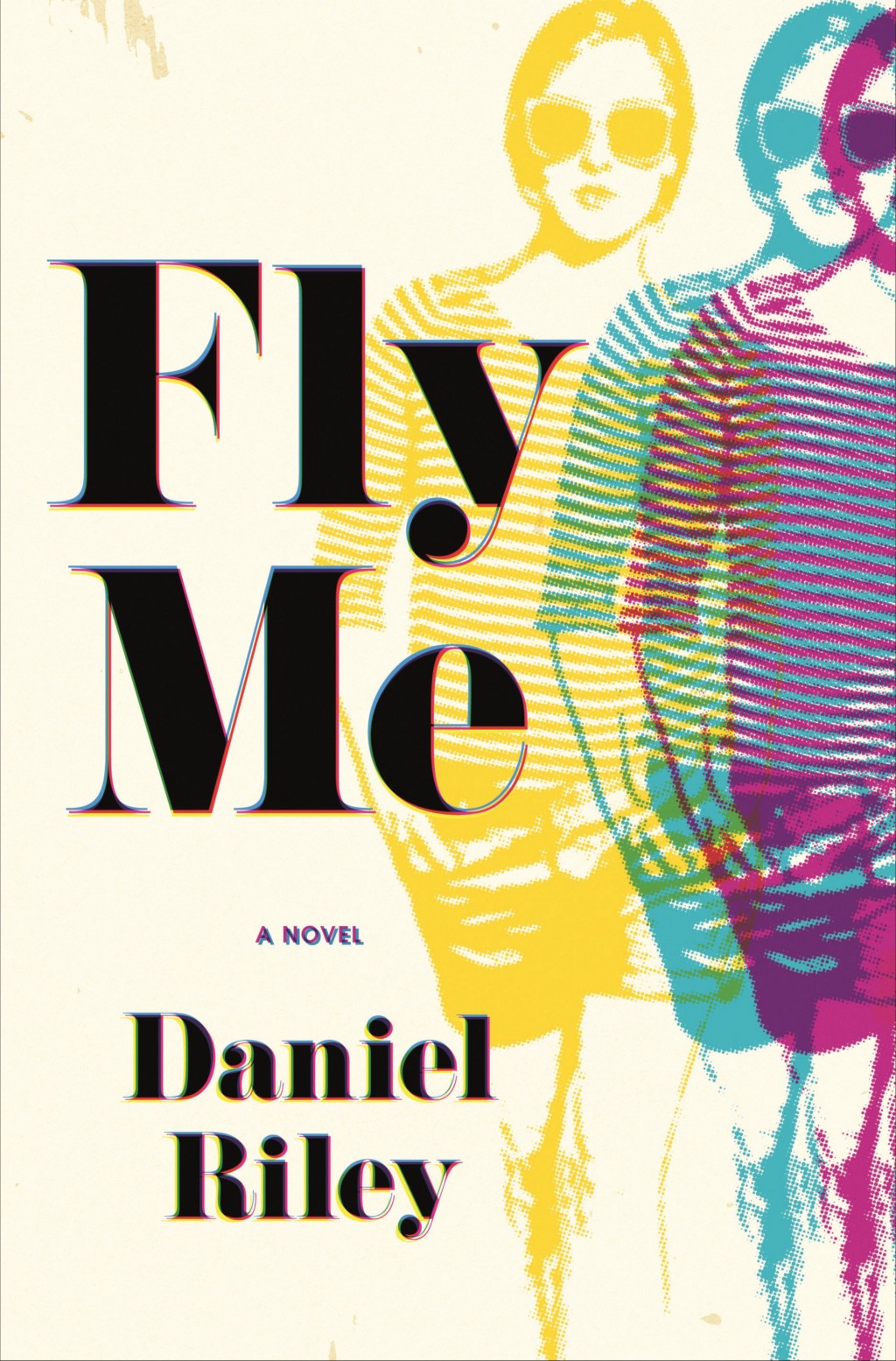

An excerpt from Daniel Riley’s ‘Fly Me’

In this excerpt, we’re thrust into the center of the early ’70s flying life of 22-year-old stewardess Suzy Whitman, who’s grown inadvertently involved with a drug-running scheme that clashes perilously with the skyjacking epidemic of the era. A mid-flight emergency leaves Suzy stranded a long way from her home base—the beaches of L.A.—and lands her at a hotel bar in Dallas where she meets a stranger worth keeping an eye on.

Fly Me (Little, Brown), Riley’s debut novel, will be published on June 6.

On the first leg of the out-and-back to New York, the pilot comes on to say they may need to make an unexpected landing. They’ve already been squeezed onto a southern route by weather over the Rockies, but this is more severe, more urgent. My God, Suzy thinks, it’s happening again. She’s in the back of the plane brewing coffee when the announcement splits the silence of the cabin. At once there’s the flare-up of a collective murmur, the sound of a lit stove top. None of the passengers in the back seem to be seeking her attention, but she can’t quite see all the way to the front. The other three girls are near the cockpit, and she makes a line forward, cautiously, pacifically.

“Miss, what is it?” says a woman in a yellow dress. Suzy can tell she’s shaped like a papaya.

“I’m heading up to check. It’s all under control.”

Each row she passes, though, she scans for signs that would suggest otherwise: bags with explosives, overstuffed shirts, shaky hands, sweaty eyes. And yet nothing presents itself ringed in red. There’s an empty seat just before she reaches business class, a window seat she’s sure was occupied. She closes her eyes tightly in an attempt to visualize the manifest, as though the darker she can make her mind, the better the odds of developing an image of the list of names and their associated faces.

But she comes up blank. And so she moves deeper toward the front of the cabin, watches the doors of the cockpit carefully. She doesn’t want to startle anyone should the doors open suddenly. She passes the compartment with her bag. What happens if she fails to make a delivery? She can’t be held responsible under these circumstances, can she?

She’s nearly to the front of the plane, eyeing the compartment, wondering if the hijackers could possibly know about the haul. The run to pay back Billy. There’s quiet up front — the three stews are seated. This confuses Suzy. But her confusion is cut off by the giant whoosh beside her, an imbalance of pressure, the cabin door unsealing, or some such equivalent. It springs her stomach. But then it settles, fizzy still but blushing, too. Someone’s flushed the toilet. Suzy steps aside, out of the way, and the elderly woman belonging to the missing seat returns to her window.

Suzy presses in to the head stew and whispers softly so that the first-class passengers don’t overhear.

“Is everything okay?”

“What?” Marcy shouts.

“Is everything . . . ,” Suzy says at the same unhelpful volume. Then: “What’s going on?”

“Weather,” Marcy says.

“Weather?”

“Gulf storm,” Marcy says, shouting still.

“Nothing else, no other problems . . .”

“Don’t look so spooked.”

“Ladies and Gentlemen, this is your captain. . . . ” And he proceeds to explain. A late-season gulf hurricane has slowed its metabolic rate and turned into a mean, doughy central-Texas mess of shit that’s forcing all planes in the area down to the ground for at least an hour.

That’s it. Suzy’s relief is rapidly overwhelmed by her distaste for her own paranoia. Here she was certain that they’d be flying to Cuba to drop off another radical in Havana, like she’d been reading about all summer. A favorite destination. She even heard from a pair of pilots that the government had considered building a fake Havana airport near the Everglades so that planes wouldn’t even have to leave American airspace. A Hollywood Potemkin village for hijackers.

But instead: just standard Texas weather. An hour on the ground in Dallas becomes two. The storm turns out to be so bad, winds so significant, that they clear the runways entirely, rush all planes to hangars. It reminds Suzy of The Wizard of Oz, and she wonders if that one was the first “It was only a dream” in movie history.

From the gate she watches out the windows as a pair of fighter jets taxi right there between the commercial birds. She feels the familiar wistfulness for the claustrophobia of the cockpit. She can make out the red smudge of the pilot’s helmet and finds it to be a shade she might like for herself if she ever races regularly again. After three hours the airline calls it — no one’s getting out until the morning.

Suzy’s put up in a room downtown with the rest of the crew. It’s still light out and not even raining by the time they get to the hotel, and so she walks down by the Book Depository and trudges through mud on the grassy knoll, mud that dries bone-light on her boots. Some of the other girls go out to dinner, but Suzy heads to the bar with another something Mike gave her — a fat one, a weird one, Doctorow’s The Book of Daniel — and orders a rib eye and a glass of Johnnie Walker Blue. And because it’s the same bottle the cowboy at the end of the bar is drinking from, he says it’s on him, a gesture Suzy waves off halfheartedly until he insists, and she gives him an overcooked smile and a double thumbs-up.

When she asks the bartender for another, the bartender says the same guy’s got this one, and the following one, too. They’re already paid for. And so Suzy waves and mouths a thank-you again but returns to her book all the same. She moves through her meal slowly so that she’s not left alone with just the drink. When she re-ups again, the man at the end of the bar stands and ticks off the number of seats between them until there’s just one left. He gives her the space of a single stool.

“You’re eating in a hotel and so I’m gonna assume you’re not from here.”

“You assume right.”

“Tupperware sales?”

“Ouch.”

“No, no, wait. . . . Replacement-cheerleader tryouts for the Cowboys.”

“Thank you for the drinks, seriously, but — ”

“Don’t do that. Gimme a clue.”

Suzy throws her shoulders back in mock posture and says “Can I get you anything else?” in an accent with big Texas hair.

“A stew?” he says, puzzled. “You sure don’t remind me of a stew.”

“Because I’m reading a book?”

“Oh boy, you aren’t making this easy.”

“I’m sorry, why don’t I look like a stew?”

“I guess I’ve just never met one out of uniform, is all. It’s like seeing your schoolteacher out on a date or something.”

“Well, voilà,” Suzy says.

He’s tall, with a thick head of close-cropped dark hair, mussed flat by the Stetson that’s resting on the stool beside him. His ears stick out a little and he’s got the nose of a prey bird. His eyes are a blue that seems plugged into a wall, and they’re roofed by a pair of bushy brows. Wranglers and double-pocketed powder-pink shirt and a bolo tie with the regal profile of a Cherokee chief.

“That’s something,” she says, nodding at it.

“This old Dallas wildcatter, this energy man, listed it for real cheap in the Chronicle, over where I’m at, in Houston. Clearing out the estate. Had that hat there and a pair of boots, too. Best I’ve seen. Came over yesterday. Guess how much.”

“How much for what?” she says.

“The boots!”

“Couldn’t guess.”

“Guess.”

“A thousand bucks.”

“A hundred and twenty bucks,” he says, slapping the bar. “Can you believe that?”

“Those there?” Suzy says.

“Nah, not wearing ’em. For my poppy. He took a new job in New York and he’s missing the Texas stuff.”

“Mazel.”

“Pardon?”

“Congrats to your dad,” she says. “And thanks again for this.”

“Don’t mention it. We’re all stuck here together.”

“Didn’t you just drive over, though?”

“You ever driven through east Texas during a storm like this?”

“I have not.”

“Well.”

“I bet it’s not that bad,” Suzy says.

“Oh yeah?”

“I bet I could make the drive.”

He narrows his eyes. “Stuck’s fine with me.”

Reports on the Cowboys-Packers game in Milwaukee have been coming in low on the radio, but it spikes now, awash in a debate over injuries, and Suzy’s barmate leans into the news.

When his attention drifts back, he says, “So you’re a stew and I’m a pilot. Bet you didn’t realize how much we had in common.”

“Oh yeah?”

“Texas National Guard.”

“You fly in the war?”

“Just Texas Guard. Kept it close to home. Over at Ellington.”

“You gonna go commercial?”

He looks puzzled. “Figuring it out. Taking a break, working on a political campaign in Alabama.”

“Politics, too?”

“Not my primary interest.”

“You’d rather be flying.”

“I’d rather be pitching for the Astros.”

“Wow, you’re all over the place.”

“Astros. Convair F-102s. Alabama senate campaigns.”

“State senate?”

“C’mon.”

“The big show?” she says. “That’s a diverse portfolio.”

“Thinking about business school after that.”

“Keep ’em coming . . . what else?”

“Nah, that’s enough from me. How ’bout one from you?”

“Well, believe it or not, I’m gonna be a pilot, too.”

“They move a lot of the girls into the cockpit?”

“Not as often as they should. I’m in training now.”

“Nothing to it once you’re off the ground.”

“That’s what the boys say.”

She doesn’t even see him order another whiskey, but there it is. He lowers the waterline of his drink with the hand sleight of a pickpocket.

“Say, what’s your favorite stew joke?” he says.

She smiles without her teeth and turns in her seat: “They’re all pretty lame.”

“Wanna know mine?”

“You bought the drinks. . . .”

“So the stew goes up to the cabin and asks the pilot, ‘Coffee, tea, or me?’” He pauses for effect. “And the pilot goes: ‘Which one’s easiest to make?’”

“I really didn’t think that was gonna be the one,” Suzy says.

“Lame, huh?”

“That’s the joke even the shrews at stew school feel okay giggling at.”

“Yeah, I like it.”

“How ’bout this one,” Suzy says. “Which do you prefer, sir? TWA coffee or TWA tea?”

“I’ve never flown TWA.”

“Ah, it wouldn’t make sense, then,” she says, chewing a cube so it squeaks.

The man mouths the riddle to the ice in his tumbler. And then he shifts in his seat and smiles, like it’s all gone to plan, like it’s working out just right for him.

“Ha!” he says. “I hadn’t heard that one. T-W-A-T, I like that. . . . I prefer . . . TWA tea.”

She sizes him up all over again.

“You don’t look much like a horses-and-lassos cowboy.”

“You’re picking up on my time back east.” He flashes a gold university class ring, and in the instant she thinks she recognizes the familiar Hebrew letters of the Yale crest. But his hands tuck back beneath his elbows on the bar before she can see for sure. “Odessa, Midland, Houston, before that. Poppy worked in oil. I went away and now I’m back. I’ve gotta say, I missed the clothes.”

“Don’t take this the wrong way, but when you’re dressed up like it, you kinda have the Jon Voight thing going on, when he steps off the bus in Times Square.”

“Still haven’t seen it,” he says. “But I know the Nilsson tune.”

Suzy smiles and finishes her drink and drops it loudly on the bar. She scrapes the last of her zucchini around with a fork and presses her plate in the bartender’s direction.

“Can I get you another drink or something?” the cowboy says.

Suzy’s got an early call time and she’s the kind of lit that’s one drink too many for a good night’s sleep and one drink short of a sure hangover. She’s making a hard break of the twenty-four-hour rule either way. And here, after thirty minutes with this traveler — this thing before her that’s hogging her field of vision, this shape that the camera in her mind has irised in on, this creature with whom she’s collided and intertwined and that she’s come to regard as the sole protagonist of her recent memory — Suzy’s growing susceptible to the idea that he might very well be the only man left in the whole world. “I’m good,” she says, lifting herself and subtly falling forward toward him. “But listen: you get something else for yourself and put in on my bill. To pay you back. The airline’s got it anyway, you know?”

He looks a little hurt, since things seemed to be going so well — but he has a nice mouth. And the longer he keeps that ring tucked under his arms, the greater Suzy’s conviction grows to see it again.

“Room 325.”

“Yes, ma’am.”

Suzy slides what’s left of the last ice cube into her mouth and cracks it in half. She steps closer and wraps her painted nails around his bolo tie. For whatever reason, that’s the moment she remembers that there’s freight glowing undelivered in her carry-on, and she feels a fuzzy heat beneath her skin.

“You understand what I’m saying? Room 325, ’kay?”

Daniel Riley is a Senior Editor at GQ Magazine. He grew up in Manhattan Beach, California, and lives in New York City. This is his first novel.

Anything That Distracts Us From Our Descent Into Madness is a Blessing

And other answers to questions you didn’t ask.

“What’s up with those fidget spinner things?” — Curious Carl

Have you seen those? They have ball bearings and three little wings and you spin it and it spins and spins like crazy. You can rest it on your thumb and just kind of watch it spin. Some light up with little bulbs. It’s the latest fad with all the kids, allegedly. There is very little in the world left to hold on to. Back into the old days, when things were getting rough, me and your mother used to go outside and split a cigarette. Before that, you could smoke butts literally anywhere. Elevators. Movie theaters. The space shuttle. Before that I think people just openly did coke and opium all the time, just to make it through the day. And what problems did those people even have? Worldwide Flu Epidemic? Sounds dreamy. Try having a crazy tweeting president! You’d beg for a lethal dose of influenza.

So, when things get rough and all seems bleak, keep your fingers busy. Busy fingers are happy fingers. They think maybe the crime rate has gone down, especially among young people, because of the proliferation of cell phones. Not merely just because of the heightened level of reporting crimes. I would argue it’s because people are too busy screwing around with their phones to commit crimes. Who has time to commit crimes when there’s all these photos to like on Instagram and all these tweets to troll on Twitter?

This week will be a long build up to Former FBI Director James Comey’s testimony in front of Congress Thursday. Or, if you prefer, the release of Katy Perry’s new album Witness. Both have the chance to determine what kind of nation we’re going to be going forward. As Katy Perry gets less infectiously poppy and more vengeful and atonal, it’s a fair bellwether into our national psyche. “Swish Swish” was not as grim a misstep as “Chained the the Rhythm.” “Bon Appetit” seems to side with French Globalism over America Firstness. But what happened to the Happy Go-Lucky Songstress of “Roar?” Is this what it sounds like when she roars, gutturally, from the her deepest recesses? Like some lost track off the Beetlejuice Soundtrack? When will Katy cheer up and make us dance again? Unfettered by the worries of this world?

James Comey’s testimony is much better in the abstract than it will be in real life. This isn’t the end of A Few Good Men. No one puts all their cards on the table to some lame Congressional committee. You give them a taste, and then you make them buy the whole thing when your memoir comes out the year after. That James Comey was keeping contemporaneous notes all along is a good thing. But if he’s upset about being called a ‘nut job’ by the guy he basically made president we will probably never know. Either the Trump Administration will block his testimony or he will fink out. Nothing good will come out of the year 2017. Except for Wonder Woman, which is a masterpiece.

So we may need to keep our hands busy for the foreseeable future. These little plastic things take a little of the edge off. If we all spin them at the very same time, possibly we can send all the pollution right up out of our atmosphere, just spin it right on up out. There is some thought that the spinners can focus us for the difficult tasks ahead. People say that we can’t be distracted. We must constantly be vigilant. The real Donald Trump of the 1990s is stuck in the Black Lodge and this new doppelgänger is determined to puke its toxins in every direction. That’s a new “Twin Peaks” reference. Should you be watching “Twin Peaks?” All distractions are incredibly important now. Anything that distracts us from our descent into madness is a blessing. You will remember not the moments of high stress and angst, but the moments you found comfort in small, stupid things.

Jim Behrle lives in Jersey City, NJ and works at a bookstore.

Doms & Deykers, "No Life On The Surface"

This again?

Weren’t we just here? Wasn’t it moments ago that we were waking up to a new week, full of dread and barely able to drag ourselves to the starting line? Didn’t we just complain about how exhausted we were and wonder how much more we could take? I guess the good news is I can copy and paste this exact block of text over and over again until it finally all comes down, because we live in a world where it’s always like this now. Here’s some music. Enjoy.

New York City, June 1, 2017

★★★★★ The clouds were puffy and pure white, and behind them was a deepish blue. Then for a while there were no clouds at all, just a thin haze that held a portion of the light aloft while the rest of it smashed on the ground and objects below. A cop coming out of the subway greeted a togaed street performer, inquiring why he wasn’t painted up yet. A new set of clouds came, spreading glory rays at the zenith and restraining the heat. A newly made stretch of sidewalk was dazzlingly pale underfoot. Every turn onto a new cross street brought with it a new, particular stripe of sky, a revelation still somehow unexpectable.

Knew Them All, Of Course

Last night at the bee.

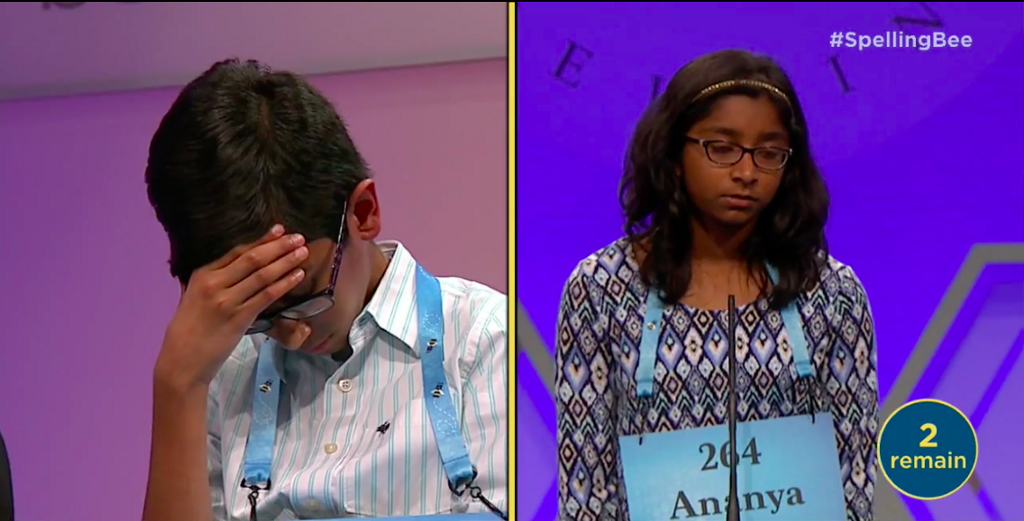

Ananya is the 13th consecutive Indian-American to win the bee and the 18th of the past 22 winners with Indian heritage, a run that began in 1999 with Nupur Lala’s victory, which was featured in the documentary “Spellbound.” Like most of her predecessors, she honed her craft in highly competitive national bees that are limited to Indian-Americans, the North South Foundation and the South Asian Spelling Bee, although she did not win either.

Unflappable Ananya Vinay wins National Spelling Bee

The spelling bee has gotten so good so fast in the last ten years that last night was an absolute spectacle. Ananya Vinay (12) and Rohan Rajeev (14) went TWENTY ROUNDS back and forth spelling words like durchkomponiert and cecidomyia like they were cats in hats. It was like watching Federer and Djokovic volley, except no one made any errors. Until the very end, of course.

The last three years have ended in a tie, so this year the Scripps people came ready with a tie-breaking test. I was ready for the kids to go behind a curtain and sit at school desks and take a handwritten test on live television, but it didn’t come to that. Ananya was victorious, and Rohan still won $30,000. You can bet next year will be even more amazing.