18 Things To Do This Weekend

Let’s not look at this as the sad pitiful end to a summer that never really was, a cold hard Winterfell of the shorts-wearing soul, but as a celebration of the coming of fall, America’s best season! It’s not “back to school” on Tuesday, it’s a fresh chance to work hard and achieve glorious things! Let’s pretend we’re well-rested and be all ready to get back in the game! So I’m going to spend the weekend sharpening my pencils and bringing out some light sweaters. How wonderful! I’m really trying to talk myself into this, can you tell???

Today’s podcast is sponsored by Audible. From this link right here you may obtain a 30-day free trial of Audible and a free audiobook. Don’t you want someone to tell you a story?

How To Talk Like Shakespeare

by Daniel Fromson

Daniel Fromson’s Finding Shakespeare is the tale of a troubled Vietnam veteran turned amateur actor named Hamilton Meadows who became obsessed with a question: what did Shakespeare really sound like? The full story is new this week from Atavist. That’s just $2.99 for a month, or $19.99 for a whole year!

A few years ago, while I was living in Washington, D.C., I became curious about a small, apple turnover-shaped landmass in the Chesapeake Bay: Tangier Island. On Halloween, 2011 — after reading about the place on and off for a year or so — I came across a story in the Salisbury, Maryland, Daily Times. A “New York City Shakespearean actor,” the article said, had spent three weeks on Tangier searching for the Elizabethan English that was rumored to survive there. “The actor’s dream,” it went on, “is to produce and stage Shakespeare’s plays ‘as faithfully as possible,’ using what theater insiders call ‘Original Pronunciation,’ abbreviated OP — referring to the way the Bard himself would have spoken the lines at the time he wrote them.” His name, it said, was Hamilton Meadows.

I would go on to spend weeks with Hamilton Meadows, then months. At first, what drew me toward him was the chance, however small, that he might really revive Shakespeare’s legendary accent. But what pulled me closer was a deepening sense of the meaning of Meadows’s dream — of its place in what he imagined as a theatrical, even Shakespearean life story filled with sudden tragedies and wanderings from Dubai to Hollywood.

The language of Queen Elizabeth I’s England is often described as the most beautiful English ever spoken. It is an idealized tongue, synonymous with a golden age that followed the barbarism of the Middle Ages, preceded the chaos of the English Civil Wars, and shaped our understanding of what came after. As the historian Jack Lynch details in The Age of Elizabeth in the Age of Johnson, this idealization caught on during the 1700s, when writers and other thinkers were stricken with unprecedented self-consciousness about their native tongue. The language, Jonathan Swift wrote in 1712, had fallen victim to such evils as “Enthusiastick Jargon” and “Licentiousness”; Samuel Johnson denounced its “Gallick structure and phraseology.” The British sought pure linguistic ancestors to emulate and found them in the Elizabethans — especially Shakespeare. “In our Halls is hung / Armoury of the invincible knights of old,” William Wordsworth wrote. “We must be free or die, who speak the tongue / That Shakespeare spake.”

A fixation on Shakespeare’s English also emerged, later but no less fervently, in the United States. As interest in his plays surged throughout the 1800s, “American writers emphasized the ‘Anglo-Saxon’ roots of American culture and celebrated ‘our Shakespeare’ as a figurehead behind which a nation made increasingly diverse by immigration could unite,” the scholar Helen Hackett has written. “In particular, American English was claimed to be purer and closer to the English of Shakespeare’s time than was the language spoken in Victorian Britain.”

Still, professional directors and producers didn’t embrace what became known as Original Pronunciation, even as they sometimes resurrected other aspects of historical performances. Perhaps they considered it an archaic curiosity — but it is more likely that they didn’t know of it at all, or feared, as London’s reconstructed Shakespeare’s Globe Theatre did, that it would sound so primitive that people wouldn’t understand it.

That all changed in late 2003, when a linguist named David Crystal offered to help the Globe put on three OP performances of Romeo and Juliet. A white-bearded Irishman who retired from the University of Reading in 1985 to lead a life of independent scholarship, Crystal, the preeminent detective of the modern OP community, is the author of more than 100 books — enough, and in enough editions, that even he has lost track of exactly how many — including The Cambridge Encyclopedia of the English Language. His investigation for Shakespeare’s Globe, like those of the trailblazing researchers whose work he consulted, relied on three main forms of evidence.

The first was spelling. During the Elizabethan era, words had not yet ossified into their modern versions, so Crystal was able to deduce pronunciations by comparing early spellings to modern ones. In Shakespeare’s First Folio, for example, “poppering pear” — a pear from the Belgian town of Poperinge, and, figuratively, a penis — is written “Poprin Peare.” So poppering must have had only two syllables (“pop-rin”), and speakers wouldn’t have pronounced the g. Examining many words, Crystal concluded that both of these traits — the compression of multisyllable words and the dropping of the g from -ing endings — were common in OP.

The second source of evidence was detailed accounts of pronunciation written by Shakespeare’s contemporaries, such as his fellow playwright and poet Ben Jonson. The letter r, Crystal believed, was pronounced after vowels, in part because Jonson was one of several writers who had commented on how people had used the growl-like “dog’s letter.”

The final clues were sound patterns, particularly rhythms and rhymes. Crystal used lines from Shakespeare’s plays to determine which of a given word’s syllables would have been stressed in everyday speech. Other findings came from rhymes that don’t quite work in modern English, such as a couplet from Romeo and Juliet that rhymes the words “prove” and “love” — the assumption being that Shakespeare never would have let such a clunker infiltrate his verse. Had “prove” sounded like “love,” or had “love” sounded like “prove”? Or had their modern sounds both diverged from a common ancestor?

Daniel Fromson is a copy editor for the website of The New Yorker. His writing has also appeared in The Atlantic, Harper’s, New York, The New York Times, The Washington Post, and Washington Monthly. This is his first publication with Atavist.

In such scenarios, Crystal would use spellings and other instances of the words to make educated guesses. He knew not only that it was impossible to re-create some sounds with precision, but also that the Elizabethans, like their descendants, didn’t all speak alike. A regional accent, he believed, would have always colored the era’s underlying pronunciation system.

By the time Crystal met the Globe’s associate director, Tim Carroll, in February 2004, he had arrived at what he considered a close approximation of true Original Pronunciation. Carroll, who was overseeing the Romeo and Juliet production, seemed anxious; despite his enthusiasm for Elizabethan costumes, music, and choreography, he had spent years avoiding what he later called “the final frontier.” Crystal was nervous, too. He had no idea how Carroll would react to sounds that deviated from Received Pronunciation, the elegant accent that most people hear in their heads when they imagine Shakespeare’s voice. RP, as it is known — the accent of the Queen, Shakespeare in Love, and legions of documentary narrators — is in fact a product of the 18th and 19th centuries, when obsessions with class, manners, and proper English swept Britain, privileging the speech of polite Londoners above provincial dialects. Adopted at public schools such as Eton, and of course at Oxford and Cambridge, RP became the accent of the British Empire, the BBC, and Shakespearean theater. It cemented Shakespeare’s air of authority — but it is not how Shakespeare spoke.

Crystal proceeded to read Carroll the prologue of Romeo and Juliet in OP. It sounded decidedly rustic. As the actors soon discovered during rehearsals, the pronunciation of r after vowels reminded listeners of Ireland or the southwestern English provinces known as the West Country. There was also the general style of speech: casual and fast, with actors breezing through short words and skipping consonants and vowels. Friends would be “friens”; natural would be “nat’ral.”

“A courtly bearing starts to feel strange,” one actor told Crystal in an email. “RP’s stiff upper lip dissolves away.” When the show finally went up, attendees said OP made the actors easier to identify with. During an intermission, Crystal asked a group of teenagers what they thought. “Well,” a 15-year-old said, in a Cockney accent, “they’re talking like us.” This conclusion, Crystal says, isn’t limited to speakers of regional British English: Since merchants and colonists spread the accent around the world, it became the spring from which all Anglophone accents flowed, such that people from America to Australia, hearing it for the first time, perceive aspects of their own speech.

Critics praised the Globe’s efforts, but their attention soon faded — as did the Globe’s, after a new artistic director came on board in 2006. Although Crystal published a book about what he called “the Globe experiment,” its influence was mostly limited to a couple of peers who attempted their own OP productions. Then, in March 2011, Crystal received an email. The sender’s name was Hamilton Meadows.

The email consisted of just one sentence: “Shooting doc on Shakespeare accents, using Taming of the Shrew for production in NYC this year, love your views.” Crystal wrote a brief reply: “I have plenty of views, but am not sure from your message how you want to hear them.” Meadows did not respond until the following month, when he emailed Crystal a photo of what appeared to be a sailboat. “Headed to Tangier Island this week to document accents of locals,” he wrote. “Will send you footage when I return.” This time Crystal didn’t reply. Crystal later told me that he viewed Meadows with suspicion, and that, compared with everyone else who wants to do OP Shakespeare, “Hamilton comes from a very different sort of background.

“There are lots of Shakespeare enthusiasts,” he said, “who are simply nuts.”

Shakespeare has always attracted misfits: the phrenologists who once hoped to disinter his skull; the Oxfordian and Baconian conspiracists who have doubted his existence; P. T. Barnum, who tried to buy his birthplace; and a loose cohort of amateurs who, for roughly as long as scholars like Crystal have pursued Shakespeare’s English, have claimed to have found it, alive and well, in the contemporary world. These adventurers and clergymen, journalists and genealogists, have historically latched onto an Edenic notion, believing that in some corner of civilization untarnished by modernity, people still speak like the Elizabethans.

Such stories clash with the wisdom of modern linguistics, which holds that Shakespeare’s English cannot be any living person’s native tongue, if only because all spoken languages are always evolving. Even a colony of 17th-century actors, stranded on a faraway island during the reign of Elizabeth I, would speak differently hundreds of years later. Still, since the 1800s, people have reported hearing Elizabethan English, or at least an “Elizabethan accent,” not only on Tangier Island but also in Appalachia, Bermuda, Cornwall, Devonshire, Northern Ireland, the Ozarks, Panama, the Bahamas, Jamaica, Nova Scotia, Virginia’s Roanoke Island, Newfoundland’s Fogo Island, the Pine Barrens of New Jersey, and the Pitcairn Islands of the South Pacific. “Though they never heard of Shakespeare,” a newspaper once reported, “the Bourabbees of Panama speak an English that sounds as if they were characters right out of his plays.”

This last example, more than most others, encapsulates the idea’s allure. In his essay “In the Appalachians They Speak Like Shakespeare,” the linguist Michael Montgomery argues that the notion that Shakespeare’s language lives on functions as “a myth of the noble savage”: it “satisfies our nostalgia for a simpler, purer past, which may never have existed but which we nevertheless long for because of the complexities and ambiguities of modern life.” The words link us to an imagined age of bygone freedom — of pirates, pioneers, poets — whether the alleged speakers are Bourabbees or hillbillies. “In the Kentucky mountains to this day there are people all of a sort who still speak Elizabethan English,” John Steinbeck wrote in 1966. Or as Emerson Hough put it in 1918, “When and what was the Great Frontier? We need go back only to the time of Drake and the sea-dogs, the Elizabethan Age…. That was the day of new stirrings in the human heart.”

Hamilton Meadows, I would learn, considered himself a throwback to exactly this sort of earlier era — an explorer, a sailor, and a man of honor who had tried to live a rambling life of extreme autonomy. His ideas about the Elizabethans, similarly, echoed those of earlier believers. “They were almost like the hippies,” he told me. “It was wild. It was absolutely insane. It was free. So that’s what we’re trying to find.”

Is there more? Yes. There is so much more.

New York City, August 28, 2013

★★ Morning was blue above, brown at the horizon over New Jersey. Wet patches on the pavement failed to evaporate; a plume of cigarette smoke hung out by its smoker on the sidewalk. Gloom seemed to advance across the office from the windows as the day went on. Thunder followed; a rain-soaked straggler arrived. Pigeons crumpled themselves into the recesses of the windows of the next building for shelter, the twitch of a wing showing that the mangling was only temporary and non-fatal. A mourning dove, sleek and indifferent, stayed out on a railing.

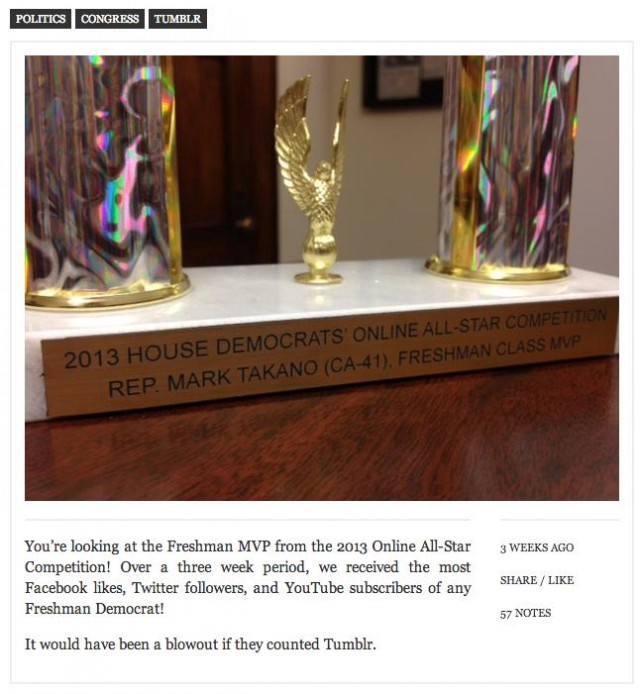

Congressional Blog Review: Mark Takano's Tumblr

by Adam Carlson

The 113th Congress: do they blog? They do, a little! And here we review their blogs. First up, gay former schoolteacher Mark Takano, of California’s 41st district — that’s Riverside County and San Bernardino County — who entered the House of Representatives in January of this year.

Who: Mark Takano (Rep-D, California) — There Will Be Charts

What: A mix of shout-outs, Vines from the Hill, and realpolitik disguised as the occasional flight of fey.

Design: 7.5/10. The buttons are big, the tags are big, and the header is kind of terrifying. Why are the letters in 3D? It’s like the page is shouting at me in a low, throaty whisper. I love the lines! I less-love but still really like the alternating black/gray/white, which feels Mod without also feeling needlessly ironic. Everything is so clean and hardly ridiculous, which is important when your blog includes GIFs of Bill Hader doing his best version of a strung-out member of the glitterati.

Community engagement: 3/10. Be kind, reblog. It’s the first rule of Tumblr, Mark. (Can I call you Mark? I do follow you on Tumblr.) The second rule is actually an appendage to the first: Have fun with your tags. “Republicans” and “House of Representatives” make your content searchable but it also makes it boring. Try flashier replacements like “zing” and “hashtag sigh.”

Fun: 8.3/10. This blog seems so fun! But there are days-long lapses in activity, as if the Internet couldn’t go and find its wise-cracking politicians elsewhere.

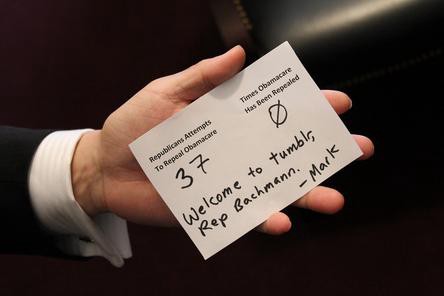

Peak: A three-way tie between “Mitch, don’t kill my vibe”, line-editing a GOP memo on immigration, and giving Paul Ryan’s latest budget proposal the black-out treatment.

Valley: “Submitting my first bill!” (It’s a less-than-gripping Vine.)

Soundbite: “Welcome to Tumblr, Rep. Bachmann.”

Adam Carlson writes things for money.

Saint Rich, "Officer"

I get a real Arctic Monkeys vibe from this one. Stereogum declares it reminiscent of Real Estate, but, as an old person, Arctic Monkeys are about as cutting edge as my frame of reference is going to get from here on out, so that’s what I’m sticking with. Anyway, enjoy.

This Witch Wrote My Book!

by Patrick Robbins

August 11th was a huge day in my life. I was at Think Coffee on Fourth Avenue. I had just finished, at age 27, my very first novel. I told the barista, who gave me a high five. This was nice of him, given that this probably happens at said coffee shop way more often than we’d like to think.

I had been working on it for two-and-a-half years, showing it to no one, periodically reading it aloud to only two people — my partner and my ex. The book was a story about the Baba Yaga, the witch from Ukrainian folklore. I first encountered her as a child in Neil Gaiman’s Sandman books and I thought that she was a really interesting take on the archetypal crone. When I began working on a novel, I wanted to write something fantastic, something to take my mind off my science-based Master’s program, and so I chose her as my subject. The novel’s title was simply The Baba Yaga. Starting out, I wanted it to be a cinematically written tale with many interweaving plot points. I would pit the titular witch against the state, exploring the idea of witchcraft as a metaphor for unofficial or covert forms of power. There would be romance, and adventure! And it would be written in five parts, because that’s a nice, digestible number.

My graduate program ended, but the novel continued — by then, it had taken on a life of its own, and become more than just a hobby. The novel was taking shape, gaining structure and depth and coherence. This was because I was genuinely putting in the work. I spent hours in coffee shops pondering this or that plot point and asking myself otherwise nonsensical questions (“But how does she even reach the city of the shapeshifters? And why would they help her? Do they have a dog in this fight?” reads one note in the margins). I was spending time on it, for lots of reasons. For one thing, I was becoming proud of it. I could read sections and think to myself, this is good. And on a deeper level, the idea that I was actually going to follow through on something like this — actually finish it, actually accomplish a big project I’d set out to do — had become intoxicating. I worked on it on the bus. I worked on it in my living room, after my roommates fell asleep. I made excuses to leave parties or meetings with friends so that I could work on it instead.

And then I finished, and I was elated. I felt proud of myself for bringing something strange and new into the world. I sent draft copies to ten or so friends, and started researching publishers who might be interested in turning it into a book. During the summer of 2007 I’d interned at FSG, and obviously I thought they’d be an amazing publisher. On the night of August 21st, I looked up their catalog on the Internet, trying to get a sense of whether or not they published work like what I had just written.

And there, shining out from my laptop screen, impossibly, was my novel. “Baba yaga,” spelled out in florid Belle Époque type. It had been written by someone named Toby Barlow.

I couldn’t believe what I was reading. I went to the “read more” section, and read as much of the book as the publisher’s website would allow. Anyone who has worked on a creative project for years will understand the horror that filled me when I realized that, in structure and in writing style (even in fucking title!) someone had written a book bizarrely similar to what I had just finished. My novel was no longer unique, no longer fresh, no longer, well, novel. I felt like I’d been gutted. I screamed. I laughed. I called my partner, who was shaken, but not nearly as unhinged by the news as I was starting to become (“Stop that,” I hissed at him at one point, when the phone went silent. “I can hear you reading.”). I don’t think I unclenched my fists for two hours. I combed through my emails to see if it was possible that I’d sent it out to anyone, some traitor who could have fed my work to this impossible doppelgänger who somehow beat me to the punch. Nothing turned up. Of course this was truly just a horrible coincidence. I slept maybe four hours.

How did this happen? I listed the similarities in my head — cinematic writing style, interweaving plot, witches pitted against the government, a plot with an older witch and a younger witch, the younger of whom begins a love affair with one of the employees of the agency persecuting the witches, a plot split into five sections — and felt like I was losing my sanity. This is impossible, I thought. All of my ideas came from my mind, and mine alone.

Well, yes and no. Here’s the thing — this author and I belong to the same culture. We are predisposed toward the same behaviors and tendencies. Yes, it is a bizarre coincidence that he and I would choose the same subject matter. But given that initial coincidence, it’s fairly easy to see how the other similarities flowed from there. The notion of alternative power structures flows fairly easily from the history of witches (Silvia Federici, anyone?), and the trope of the older witch and the younger witch — the former as crone, the latter as seductress — can be found in mythological traditions the world over. And as far as writing style goes, both Toby Barlow and myself are writing at a moment in literature that is increasingly cinematic, as faster and more interactive forms of media inform our collective consciousness. This is the lesson that I am now learning, and would advise any other writer who finds themselves in my position — what seems maddening and impossible is actually really fairly likely when you consider that all of us are products of our culture. If you start writing something, anything at all, then there is always the chance that you will find yourself the butt of some horrible Barthesian joke. It is humbling, and it will probably make you scream at people you care about, but you probably shouldn’t camp outside the other author’s house in a tent or send dead birds to his publicist.

And in the meantime, remember that your work is probably more unique than you think. Yes, in the heat of the moment, you are more inclined to see the similarities than the differences. But there are always differences. From what I can tell of Barlow’s book, which is actually called Babayaga — another difference! — mine is more of a straightforward fantasy tale, and focuses more explicitly on witchcraft as a metaphor for anti-capitalist thought. And mine will probably be more graphically oriented, with a series of illustrations from a designer friend of mine. Which is not to say one is better than the other. Maybe Barlow’s is great! I’m glad that he wrote his, and I look forward to reading it. The point is that they’re different books. I am still going to try to publish mine, and I’m betting there’s room for both out there in the world.

The sky is not falling if someone writes something similar to what you’ve written. Neither is everyone ripping you off. Remember when zombies were a thing? That’s just how the culture works. When things like this happen, you shouldn’t stop writing, or get discouraged. Your writing is still yours, and you owe it to yourself to pursue it with renewed vigor — as soon as you get over your hangover. Because that first night will be rough.

Patrick Robbins is a writer and activist living in New York City. If anyone wants to publish his manuscript, let him know; it’s a buyer’s market these days. Photo by Eduardo Mueses.

Dogs Snack Better Than You Do, And Why Shouldn't They, You Suck

Dogs are eating as well, if not better, than many humans are, observes a woman who takes inspiration from one of the world’s finest websites.

The 8-Hour Year Sounds Kind Of Dreamy Right Now

“A headline for a report in The Week column on Tuesday about Kepler-78b, a planet discovered 700 light-years from Earth, misstated the period of time covered by a single rotation of a planet around its sun. Because Kepler-78b orbits its sun in a little over eight hours, it has an eight-hour year, not an eight-hour day.”

Elizabeth Fraser Is 50

Does Elizabeth Fraser have the most beautiful voice in popular music? On most days I’d say yes, so on this day, which is her birthday, it would seem churlish not to reaffirm that opinion. Above, a track from what I controversially but correctly identified as her band’s best album in an earlier post. Below, her (and possibly anyone ever’s) greatest supporting performance. Happy birthday Elizabeth Fraser.

Metaphor Unsuitable

“Is a steak sandwich bad for your health? Absolutely. Does caramel ice cream taste so good that it induces cravings in some people? You bet. Do sweet, fatty foods like Crack Pie light up the same pleasure centers of the brain that are activated by addictive drugs? Sure — in rats, at least. And yet food is not like crack in several significant ways.”