Classic Morrissey

by Rebecca Rego Barry

Publishers have always been cultural arbiters, and throughout publishing history they have used their power to harness the “classic” label — and its attendant packaging — to turn a profit. Bestowing classic status on a book has the effect of redefining a book’s history: sometimes prolonging its shelf life, sometimes uplifting it from the deep backlist. For some, this manhandling has eroded the potency of the word “classic” as a marker of timelessness, high aesthetics, or universality — words that are slippery and subject to intense debate.

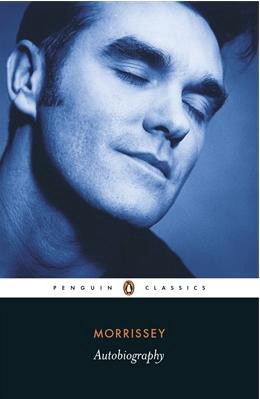

Such is the case this week. The Brits have their knickers in a twist over the fact that Morrissey’s Autobiography was published today under the Penguin Classics imprint. Boyd Tonkin wrote in the Independent that the book would “wreck overnight the reputation of a global brand that, since 1946, has built up its worldwide trust on the basis of consistent excellence, expert selection and a commitment to pick and sell only the very best.” Brendan O’Neill, writing in the Telegraph, was angry that the musician’s memoir is “not a modern classic, but a classic classic,” suggesting that there is latitude in the term. The Mirror snapped that the publication “undermines every possible definition of the word ‘classic’.” The Guardian was irritated by the “dumbing down” of such a “high-minded enterprise” as Penguin Classics.

It’s true, E.V. Rieu was a classicist, and he launched the series in 1946 with high-minded Homer. He originally envisioned the imprint as translations of Greek, Latin, and European titles through the late nineteenth-century. It evolved from there, eventually surpassing 1,000 classics, including many, many classics that this former English major would be unable to argue are either timeless or universal. But evolved is the key word here. As the literary critic Frank Kermode once wrote, “the renovations of the classic, in one epoch after another, are a matter of history, and to renovate is to acknowledge one’s modernity.”

Tonkin insisted that Morrissey ought not to be shelved with the other M’s in the esteemed Penguin Classics line-up, alongside “Montaigne, More, Milton, Marlowe, Melville, Machiavelli and Michelangelo.” There was a time when I would have agreed with that exclusionary position — I once wrote an entire master’s thesis on the power of the “classic” in book publishing — but does Mandelstam (Selected Poems) fit better? Or Multatuli (Max Havelaar) or Maturin (Melmoth the Wanderer)? I’m not listing these lesser-known talents to make a statement about who belongs and who does not, but it is worth noting that classics series are not all Shakespeare and Austen, and that economic factors, marketing imperatives, and the personal likes of publishers have always played a role in editorial selection, even in the theoretically untouchable realm of classics.

Brendan O’Neill’s overly simplistic statement that “A classic is a book that is judged by posterity to be an outstanding work” is topped only by his incensed wonder that “a couple of men in suits at Penguin’s head office” were able “to decree, behind closed doors, that Morrissey’s autobiography is a classic.” That’s what publishers do! In his memoir about the early days of Random House, Bennett Cerf wrote of Modern Library publisher Horace Liveright, “If a girl he was trying to win said, ‘You ought to have this book in Modern Library,’ and it meant a weekend at Atlantic City, he’d put the book in.” Cerf further reported that when he took over the Modern Library in 1925, he had to weed out titles that “Liveright had added because of some whim or to please some author he was trying to sign up or to show off to somebody.”

O’Neill’s claim that Morrissey’s Autobiography is “a relativistic denigration of those classics whose worth we as a species have already agreed upon” is extravagant at best. I have never agreed that Theodor Fontane’s Effi Briest is a classic, and yet there it is in the Penguin Classics catalog. To be fair, I have never read Effi Briest, nor have I read the majority of the thousands upon thousands of “classics” available in the catalogs of Oxford World’s Classics, Bantam Classics (which reissued a good chunk of the novels of Thomas Hardy), Barnes & Noble Classics, Cameo Classics, Harvard Classics, Modern Library Classics, New York Review of Books Classics, Perennial Classics, Puffin Classics, Scribner Classics (which runs all the way from The Yearling to Robinson Crusoe), Signet Classics, S&S; Classic Editions, Verso Classics (includes Althusser’s For Marx!), Vintage Classics, or Washington Square Enriched Classics, not to mention Everyman’s Library or the Library of America. (The Library of America list, incidentally, begins with Melville and Hawthorne and recently blew through classics by Jack Kerouac and Laura Ingalls Wilder.)

The literary canon is a largely imaginary list. (Also an expected one. When Encyclopedia Britannica rebooted its “Great Books of the Western World” series in 1990, it added zero works by people of color and works by only four women to its canon.) And while “classic” may be a nebulous term, in a published classics series, we have a set of material artifacts, thousands of them, all uniformly dressed — “in the familiar black livery” as Tonkin described it — all standing neatly in a row. Tonkin said he believed “that black jacket will still lend” the Autobiography “an unearned aura.” Is it that he just hasn’t earned it yet, baby? Or do we truly believe putting a Penguin on the cover of a book instantaneously confers status upon it?

The whole ruckus is classic Morrissey. He pulled a similar prank back in 1986, when The Smiths switched record labels and signed with EMI. According to Tony Fletcher’s new biography of the band, A Light That Never Goes Out, when asked which EMI imprint he wanted, Morrissey chose HMV, “His Master’s Voice,” the first to use the word “POP.” By the eighties, however, HMV had become a classical music label — not suitable for his brand of post-punk pop. Still, Morrissey got his way.

As he does now with his Autobiography, bound in the uniform design so dear to readers’ hearts and minds. The irony cannot be lost on a man who wrote a song called “Paint a Vulgar Picture” about how record company executives make money by re-issuing old material in different sleeves. With a rush and a push (and a wink) he elevates his story to “classic,” no better and no worse than anything else with the iconic little signifier on its cover.

Rebecca Rego Barry writes bookish essays, articles, and reviews. She is also the editor of Fine Books & Collections magazine. Find her at Rebecca Rego Barry.

New York City, October 16, 2013

★★ Not oppressive but repressed, dim and humid and of indeterminate temperature. It was not cool enough to immediately relieve the heat from a rushed shower and the bustle to get the preschooler out the door. The clouds, a semi-smooth gray, relaxed to a loose white webbing on blue by late morning, only to tighten again. Some blue remained, but the light was only cloud-light.

Time To Die

Oh, look, it’s an appreciation of The Strokes’ second record, which came out ten years ago.

I Can't Hear Myself Drink

“Ever wonder why there is loud music playing in so many bars, even though it makes it almost impossible to have a conversation? Newly published research suggests one good reason: It inspires faster drinking, at least among young women.”

The World's Most Terrible Alarm Clock And Other Intentionally Uncomfortable And Hilarious Objects

by Emma Whitford

When Lydia Cambron was tasked with interpreting the word ‘ruffle’ for a group show at Portland’s White Box Gallery this summer, she started thinking about daily disruptions. Outside of the tech world, disruptions usually have negative connotations — a flat tire, a stain on a white shirt, a smashed iPhone case. But Cambron, a Portland-based industrial designer, prefers to think of these disruptive ruffles as beneficial. She believes that being aggravated, pained even, can force us to address our more deep-seated anxieties and insecurities. Once you can wrap your head around accepting, and even appreciating, discomfort, imagine three products that facilitate it. That’s the idea behind Twice Daily, Cambron’s three-pronged conceptual project.

• The Personal Weight is an eight-pound purple cylinder reminiscent of a sex toy, which adds extra weight to a backpack or purse. (It’s phallic enough that you’d think twice before taking it out in public).

• The Obstacle/Alarm Clock is a clock tethered to an inflatable, transparent tube. When the alarm goes off, the only way to silence it is to pump the tube full of air. This slowly deflates over the course of a day, all the while forcing anyone in the vicinity to navigate around it.

• Itchy Accessory is a suspenders-like garment worn under clothes that gives the wearer a private itch.

I talked with Cambron, and she explained why she felt compelled to create three distinctly uncomfortable objects.

So each of the three objects — the weight, the alarm clock, the itchy garment — symbolizes a behavior.

Right. The weight is all of the anxiety that is weighing you down, until it gets so heavy that you’re like, ‘Well, fuck it! Why am I carrying this around anymore?’ Then the alarm clock is the bad behaviors that implicate your family and friends. They are inhibiting, but they are so tethered to your daily routine that you don’t bother trying to pluck them out. And then with the garment, you’ve got this itchy thing that looks like an undergarment — something that’s part of your daily routine of getting dressed. It’s like those secret securities that we adopt, not realizing that they do more harm than good.

What’s an example of a security that does more harm than good?

The most basic I can think of is putting on a bunch of makeup in the morning. You do it because you think that you need to. But really it’s like, no — you’re just kind of dependent on it. And when it’s not just right, you’re uncomfortable. But you’re not noticing the damage that it’s really doing. You think of it as a sort of security that you need.

There must have been other products that occurred to you, before you settled on these three.

Oh yeah. Some of the other ones I had were like, ‘Oh, maybe there could be a cinderblock that you would keep on the side of your bed.’ Every morning, you would stub your toe on it. And then I thought about having conductive tape that you would put in your doorway. It would give you a little zap if you touched it. You’d forget that it was there, and get zapped.

Wow.

Yeah. They’re jarring. Another one was a machine that would just continuously blow up a balloon. But the rate was always different, so at some point it would pop. And you would never know exactly when.

That’s so anxiety-inducing.

Yup.

You really like things that are unpleasant.

I’m interested in uncomfortable and embarrassing behaviors. They’re so relatable! But because they are unpleasant, we tend to shy away from them, or assume that they need to be hidden. I think that by looking straight at these behaviors, by trying to understand them, we can learn a lot about ourselves.

Phallus aside, Twice Daily seems to be more about discomfort than embarrassment. What inspired you to hone in on the former?

I had recently heard an interview with James Murphy from LCD Soundsystem on “Fresh Air.” He talked about turning up the volume at his shows to a level that isn’t damaging, but is loud enough to create this really intense visceral experience.

Intense in a good way?

I like the idea of taking something that is a negative, or seen as a negative, and turning it into a positive by jacking it up to a certain level. When we have life-changing moments, they’re usually spurred by some sort of intense event, that in hindsight you’re like, ‘Oh, well, that was a good thing.’ Or, ‘I’m glad that happened.’ But while it’s happening, it’s really shitty.

So this is one way to spur those moments.

Yeah. I got interested in trying to commodify that disruption. Because I obviously can’t create someone else’s life-changing experience. That has to come from within. What I could do was create little things that make you uncomfortable. If you’re already upset and you can’t find your keys, that can spark something. You start bawling. Then you’re like ‘Oh, okay, I’m actually really upset about this other thing.’

What types of other things?

Maybe the negative opinions you have of yourself, or the fact that you’re stubbornly holding on to a harmful relationship. Twice Daily pushes you out the door before you’re finished getting dressed. Like, ‘Sorry! Here you go! Now just deal with it.’

Did you feel the need to test out a lot of different scenarios while you were developing the project?

No, I decided on all three objects at the sketch level. With my final picks, I knew what they might feel like. They’re not too foreign. The balloon and the tape were a little too weird.

Now that you mention it, I can imagine seeing the products in Twice Daily on the shelf in Duane Reade. They all have familiar elements.

I wanted all of the objects to look at least kind of unassuming, and even a little desirable. So they don’t recall a strange medical device, like a knee brace. I like that they look appealing, but then actually do that thing that’s really uncomfortable.

I keep thinking of that scene in Monty Python and the Holy Grail when the monks hit themselves on the forehead with wooden boards. Do you remember that scene?

Ha, no! It’s been a while.

My knowledge of what they are parodying is definitely minimal. But is it possible that you were inspired by religious flagellation?

I haven’t actually thought about that. This is a fairly intuitive and personal project. But I do like that idea of administering something that you know is going to be difficult. You do it because you see this ultimate gain. When I was working on the project, someone told me about this 30-day cold shower challenge.

Oh yeesh.

Some guy did a TED talk about it. It’s like, if you can handle five minutes of being uncomfortable, alone, then you’re good. And if you can’t, then you’ve got bigger problems.

This sort of stuff clearly has purchase in our society. What has the feedback to Twice Daily been like? Do people seem to get it?

It gets a lot of laughs. And that’s intentional. I like to start things off with humor, and from there, get into that deeper conversation. I like to think of humor as a Trojan horse. On the outside it’s very palatable. It’s quick and easy. You’re immediately engaged. And then you start to read into it.

Imagine that you’ve been tasked with actually getting Twice Daily on the market. Can you think of a part of the country, or even the world, where you might find some interested buyers?

I guess anywhere that life is okay enough that people are trying to be introspective. I mean, Twice Daily is sort of similar to meditation retreats and diet pills. People want life-changing experiences, and moments of clarity. Imagine if people decided that there was value in personal disruption. Then the market would immediately go up for a commodified version of it.

I’ve been meaning to ask where the name comes from.

Well, I like that it sounds sort of medical. In my original presentation, the caption was, ‘Prescribe Disruption.’ It’s the idea that these products are something you’re using to get better, like vitamins. The full title is actually Twice Daily and Continue as Needed.

Oh!

It’s like reading a prescription bottle. Here are the instructions, here’s what you do. Call me in a week.

What prescription of Twice Daily would you give yourself?

I would try all three. But when you stop taking cream or sugar in your coffee, at first it’s like, ‘Ah! This is gross!’ and then you get used to it, and you don’t want to go back. So I worry that I would just adapt to them.

So maybe you could switch from one to another. Once the effect of one wears off, you can try the next?

No, I would totally try them all at the same time. I mean, I’ve been doing the cold shower thing, and I love it. Intense immersion — that’s my strategy.

Emma Whitford is an editorial assistant at New York magazine. She also enjoys reviewing fiction for Publishers Weekly. She is, deeply, a New Englander. This interview has been lightly edited.

Cookbook Good

I’m not gonna lie to you or be all coy and faux-humble, I’m a pretty good cook. I am also old and set in my ways and blah blah blah, the point is I don’t do a lot of cooking out of books any more because I know how to make what I like and I’m no longer interested in following directions. So with all that disclaimed I want to say that Andy Ricker’s Pok Pok: Food and Stories from the Streets, Homes, and Roadside Restaurants of Thailand seems so far to be an amazing addition to the tiny library of things I actually look to when I’m in the mood to make something I wouldn’t normally. And I am someone who has stayed far away from the restaurant, which was 2012’s most insufferable New York opening. (Because of the hype, I mean. I’m sure Andy Ricker and the restaurant are perfectly lovely or whatever.) Anyway, I’ve played with a couple of the recipes here, and even though I haven’t followed the instructions to the letter things have still come out very well, so keep that in mind. It’s a good-looking book that would probably make an even better gift, maybe buy it now and give it to someone instead of having to go to dinner with them in Brooklyn for the holidays. Anyway, what I want you to take away from this whether you buy the book or not is that I am really good at cooking and I don’t care who knows it.

Once Bears Learn To Drive All Bets Are Off

“Experts say bears know how to open unlocked car doors, so it’s best to lock your car and not leave anything ‘smelly’ inside.”

— This is probably good advice even if you live in a less bear-intensive area than Truckee, CA.