We Were Not On A Break From Global Warming

“A new study has found that global temperatures have not flat-lined over the past 15 years, as weather station records have been suggesting, but have in fact continued to rise as fast as previous decades, during which we have seen an unprecedented acceleration in global warming…. Two university scientists have found that the ‘pause’ or ‘hiatus’ in global temperatures can be largely explained by a failure of climate researchers to record the dramatic rise in Arctic temperatures over the past decade or more.”

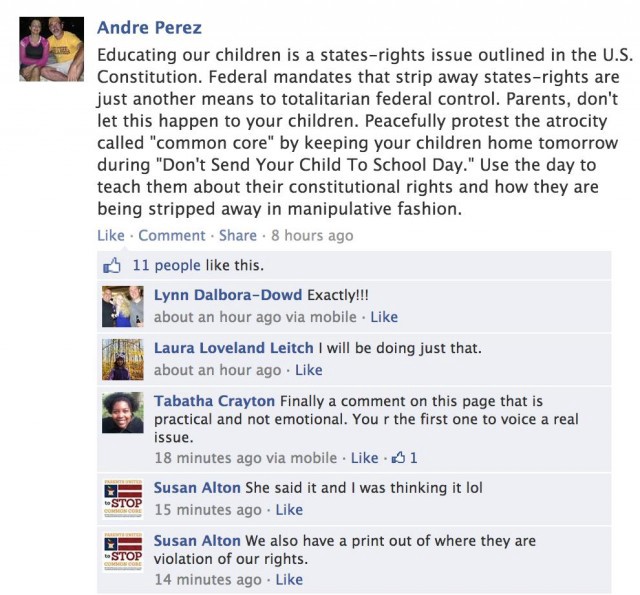

Parents Pull Kids From School To Protest Barbara Ehrenreich, Eric Schlosser, Bill Ayers and Justin...

Parents Pull Kids From School To Protest Barbara Ehrenreich, Eric Schlosser, Bill Ayers and Justin Bieber

Parents protesting the “Common Core” curriculum on the grounds that it promotes tyranny and/or makes their kids feel stupid are keeping their children home today. This is basically a protest of parents who are too lazy to home-school their kids. If you’re not familiar with the opposition to Common Core, this policy paper blames Hillary Clinton, Bill Gates and Bill Ayers and protests the literature being taught in schools, all while not being able to use commas properly: “Typical are adaptations of popular adult nonfiction books like Fast Food Nation, the socialist tract, Nickel and Dimed, and books about teen idol Justin Bieber.” And the most damning truth of all: “What Common Core will in effect do is allow the infusion of ‘social justice’ objectives and a leveling of all students.” Oh noooooo.

Hello, Welcome To Blockbuster, May I Help You

by Erik Bryan

I graduated high school in 1997 and I went to work at the Winn Dixie deli counter, which totally sucked. I was still living at home and that fall I enrolled at Tallahassee Community College. I was more unsure of my future than at any other point in my life before or since.

A friend from high school had recently been hired at Blockbuster, and he got me a job there too that fall. Blockbuster was a step up. Not only did we not have to handle foodstuffs, but we also got free video rentals — although we didn’t get health care, or vacation, or sick days.

But I cannot overstate the appeal of free video rentals. I moved out of my mom’s place shortly after I started working for minimum wage at Blockbuster. The majority of what little disposable income I had was already going to movie theaters. My friends and I would go to a movie nearly every night; theater-hopping stretched your ticket price a little further. This was well before high-speed Internet was widely available; one could not simply watch anything at any time one wanted. (I didn’t even have an email account yet.) Movies, in a small town with not much else to do, were eclipsed only by music, and only barely, as life-sustaining necessities. There was simply no joy to be found in a life without them. How simultaneously pathetic and distantly enviable that my satisfaction then was so simply attained by working for a company that let me get high on their supply.

Tallahassee is a big college town, and FSU is known for being one of the best film schools in the country. Students with a dream of becoming a screenwriter or director often ended up working at video stores around town, many considering themselves the next Quentin Tarantino. I had no such aspirations, but working with these people opened me up to an appreciation for film as art. We talked about our favorite movies and directors constantly. With rare exception, I still don’t care much for Godard, but I will fight you if you talk shit about Truffaut.

We picked movies for our employee favorites shelves more carefully than we picked our majors. We were undoubtedly insufferable, at least to anyone who didn’t revel in accusations of pretentiousness. We judged customers based on what they rented. We were teenagers, and we knew better.

Blockbuster was founded in Dallas by a man named David Cook in 1985. VCRs had yet to become ubiquitous, but it was clear they would. My family used to rent videos at an electronics store named Curtis Mathes. My younger brother probably wore out their copy of Rikki-Tikki-Tavi. What made Blockbuster and other video rental companies that began springing up then unique is that they were not augmenting their real business with the rental of VHS cassettes. That was their real business.

The previous year, in 1984, the floodgates had been opened for home video. A legal battle between Sony and the film industry over the invention of its Betamax home recording device was brought before the Supreme Court. The court decided that home recording did not constitute copyright infringement, and provided cover for the wider distribution of not only Betamax (which would justifiably die out because of Sony’s own attempt at format dictatorship) but VCRs. What the film industry learned, as most entertainment companies begrudgingly learn after fighting new technologies, is that their industry would not suffer from the proliferation of VHS. Quite the contrary: selling a product for nearly $100 that cost them a few dollars to make turned out to be good for business.

What’s that, you say? Nearly a hundred dollars for a VHS cassette? Yes. As anyone who worked in a video store, or someone unlucky enough to accidentally damage or lose a VHS can tell you, the film industry made sure of a healthy return on its investment by charging between 60 and 100 dollars for each individual VHS cassette it released. This was part of a special deal created between the studios and the video rental businesses that helped keep both in the black. New releases were extraordinarily priced precisely so that Blockbuster and others were the only companies with the overhead to buy several copies and profit on the investment before reduced retail prices were made available, usually months later, for sale to the general public. That this kind of backdoor deal existed is all the evidence necessary that a corrupt industry was in need of comeuppance. This is every bit as egregious as the RIAA making deals across labels that CD prices would remain around 20 dollars a pop. When DVDs came out, perhaps Blockbuster and other chains had gained enough stature to bargain more effectively, because those were priced for retail at around 20 to 30 dollars immediately upon release.

Because of the high cost of VHS, I became a good deal more educated about the general cluelessness of consumers while working at Blockbuster. They didn’t know what they were signing up for. Why do you think we insisted on having each customer’s credit card number? This is something I literally asked some people after they left a copy of Nine Months in their plastic-warpingly hot car, or their kid tore the tape completely out of a Pokémon video. I still feel terrible that I sided with this underhanded bait-and-switch capitalist ploy by the entertainment industries against its unsuspecting consumers. My only defense is in the cruel treatment I received from some customers, people I’d have otherwise sided with against my faceless corporate overlords, had they not treated me as subhuman scum.

That was another part of my education, and one that everyone who’s worked in the service industry learns real quick. People are safely divided into two categories, exclusively determined by their treatment of service industry reps. I suspect only IRS employees receive more open hostility. I was cussed at, screamed at, and on rare occasion threatened by total strangers, adults who had signed a contract with a decidedly for-profit business to pay for any and all damages to the product they were borrowing, to say nothing of the battle over late fees that they’d also agreed to pay.

What little power I did have at Blockbuster was the ability to make late fees go away. Poof. We were absolutely not authorized to do this by management, but we all did it to greater or lesser degree depending largely upon our treatment by the customers in question. If you were a good customer, I might remove your late fees with a few keystrokes. If you barged into the place and started bellowing about what a great customer you were, especially if I’d never seen you before, and demanded that your late fees be removed, I dug in. You can take that up with our store manager, I practically sneered at them.

Were late fees fair? Probably not, even though customers had signed that rental agreement. In 2001 Blockbuster settled a class-action lawsuit by paying out nearly $10 million over their late fee policy. In 2005 they were sued again for advertising a “no late fees” policy that included fine print saying that after seven days of late fee accrual, customers had bought the video or game, and their credit card was charged accordingly. Blockbuster’s policies were practically predatory, teetering on the edge of extortion. How exactly did a rental chain with such a squeaky clean, family friendly image come to act so thuggishly?

In 1987, a large share in Blockbuster was purchased by Wayne Huizenga and two of his associate executives at Waste Management, Inc. Huizenga eventually came to control the company, and his business acumen is largely praised for making Blockbuster the largest video rental chain worldwide by the mid-90s. Of course, “business acumen” can mean a lot of things to a lot of people. By the time of Blockbuster’s buyout by the CEO of Waste Management, his garbage disposal company had been involved in a litany of legal suits ranging from environmental violations, bribery of city and state officials, price fixing, and monopolizing. The company paid out millions in settlements.

Huizenga’s “acumen” pervaded the way Blockbuster operated, too. Each store had a full-time employee whose entire job was relegated to seeking collections on late fees and damaged goods from customers. There were surveillance cameras trained on the registers and the safe in the back room. (Granted there was a possibility of outside robbery, but we all knew that employees stole from the company far more often. The cameras were there to catch us.) Each store had a monthly inventory count. Even though Huizenga had sold Blockbuster to Viacom in 1994, these practices remained in place. The monthly inventory was a particular pain because, since the stores were open until midnight, it meant that once a month we had to stay there, sometimes until 3 or 4 a.m. depending on the motivation of our manager or team members, and we couldn’t begin until the store closed at midnight. Every single item in the store — every video, every toy and promotional item, every individual package of candy or popcorn — was scanned and accounted for. That part was beyond tedious.

But we packed the store with our friends, like every company does to some extent. I got my roommate a job there after the local music shop he worked at went belly up. It caused some discord, because I was technically his boss, but years later I would not only be his best man at his wedding, but I’d end up working for him when he and his father started their own live sound engineering company. We got a few other friends from high school jobs there. One of them started dating another employee and shortly thereafter married him. Another was a girl that let me stay with her when I first moved to New York and knew no one else in the city.

Our store manager when I started was a middle-aged woman named Vicki, who I genuinely came to regard as a mother figure. One of my other roommates, who worked at the Publix in the same shopping center, said that whenever he came into the store we all seemed like a grade-school class, running around like happy children to please Miss Vicki. I couldn’t exactly argue with him. When Vicki announced she was leaving the store and getting married, some of us cried, and I’m sure the rest of us felt like it. I lost touch with her over the years, but I still think about her.

Since my friends knew where to find me, my personal life often followed me to the store. (This was also before everyone had a cell phone.) Fallouts with romantic interests would become exceedingly uncomfortable conversations in the aisles. I actually got one kid transferred to another store because he was moving in on my ex right after she left me. I’m not proud of it, but I was desperate. We partied together, and too much. We went to each other’s shows, and played music together, and tried a lot of things we’d never tried before. An acid wave passed through Florida in the late 90s, and a new and predominantly digital strain of psychedelia was taking hold of the culture. Customers who believed our young staff was brain-dead and vacant-eyed maybe did not fully appreciate that some of us had been up all night communing and commiserating over the nature of our farcical mortality with nameless pagan forces far more ancient than their Judeo-Christian counterparts. I imagine customers should still consider this possibility.

What mattered to us the most though was film. While we knew Huizenga was no longer our boss, we knew his corporate, all-business attitude was what had made Blockbuster what it was. Huizenga, it had been reported, rarely even watched movies. He saw videos as a product, we thought, nothing more. When Viacom purchased Blockbuster, we mocked the mainstream pabulum it mostly produced. This was a time when acting like Randall in Clerks, even appreciating Kevin Smith as an artist, was deemed culturally appropriate. I know, I know.

One of the most offensive episodes to our snotty young cinephile set happened when James Cameron’s bloated, over-awarded epic Titanic came to home video. (I should probably add that, for as discerning as I consider myself in these very important matters of taste, I was never above renting and delightedly watching, say, The Rock or Spice World when they came out. I judged movies harshly, but I’d happily watch just about everything.) Blockbuster had a midnight sale on the Monday before Titanic was released, to allow totally tasteless customers a chance to watch all 194 minutes (stretched over two VHS cassettes!) that night. Earlier that day, one loathsome woman paraded into the store gushing about Titanic, asking if we were excited about its release. We exchanged looks; no, we were not excited, we told her. “But it’s the best movie of all time!” she said, parroting the studio’s marketing copy used to hock the video release. (I hope everyone understands by now that advertising absolutely works.) We rolled our eyes and got back to work.

That night a line of about ten customers bought or picked up their pre-purchased copy of Titanic. It took all of 15 minutes, but we had to stay open until 2 a.m.. I can’t remember what we put on to watch instead of the stupid trailer tapes (which featured Celine Dion singing that goddamn song over and over and over), but it turned into one of the best nights of mayhem at work. At night we’d even stay and watch movies after we’d gotten rid of the customers.

And some of the customers were great. Some of them asked for my recommendations, and actually appreciated them. Some of them watched all the movies on my employee favorites shelf, and then talked with me about those movies!

The death of Blockbuster is the death of the employee favorite shelf. With Netflix and Hulu and Amazon having rightfully eclipsed video rental stores, the recommendation is now largely accomplished by algorithm. (I also wonder how David Foster Wallace, in his otherwise brilliant Infinite Jest, could think that the near future of entertainment consumption would center around physical cartridges. Broadband access was still pretty limited, but its expansion was inevitable when the book was published in 1996.) If you didn’t agree with my taste in movies, there was definitely another employee you would agree with. There was someone for every customer to talk about movies with working at every video store in the country. Now we have Neflix’s “Top Picks for Erik,” nearly always insultingly off-base. There’s some human involvement behind the scenes for these streaming services — at Netflix, 40 freelancers tag metadata, making associations between movies and TV shows that no computer can yet make on its own — but that person is so buried behind the work of 800 engineers that he or she doesn’t exist for modern consumers in any meaningful sense.

Whether you agreed with me or thought I was full of it, customers at my store knew my name and face, and I hand-sold movies that I cared about. Social media, and general cultural connectivity, has helped put to bed the notion that someone who works at a store may have a privileged or even expert view of its products, but I don’t think any rational person would agree that Yelp reviews or Goodread reviews or YouTube comments are going to accomplish the same end.

Now, as Blockbuster closes for good, I watch at least 10 hours of Netflix a week — a company that perhaps Blockbuster should not have declined to buy 12 years ago for $50 million. The new ways are superior, and certainly more fair to consumers, but aren’t perfect. There are things we’ve lost, if we won’t mourn the stores themselves. The physical locations, usually deep in a strip mall, were an eyesore. These spaces will not magically revert to forest and veldt, but will be replaced by some service industry equally gaudy and incorporated. Whatever we still can’t get online will remain in our public spaces, and for the time being that’s quite a few things, but now we know it’s best not to get too attached. Every company has its day. But companies are not people, nor are they art. Their time is limited and incidental in a way that movies and friends to argue about them is not, and that is precisely as it should be.

Erik Bryan is yet another writer living in Brooklyn. He is also an editor at The Morning News. Blockbuster photo by Ben Schumin.

Anita Gates, Prophet

We all laughed at Anita Gates back in 1999 when she wrote, “In the year 2015 or so, it’s going to be embarrassing. Young novelists and reporters will probably be using terms like Charizard-like or Squirtle-like in their work and insisting to their much older editors that everyone knows what they mean, everyone who ate and slept Pokemon as a child, anyway, which will be the vast majority of young adults.” But who’s laughing now? NOBODY.

Polvo, "Light, Raking"

Soon enough Sunday will find you looking at the clock as the light fades and feeling the dread as another weekend dies, a new week looming on your tired horizon. But for now it is still Friday, and the week is almost over. It’s all anticipation at this point. Before you waste the time you’ve got and come out with little to show for it but a sense of sorrow and regret hold tight to this moment where everything is full of promise. The weekend is almost here, people. Let’s get ready with some Polvo.

Move Over, Mayans, Here's The Viking Apocalypse

“Experts are predicting the end of the world will take place on February 22, 2014, coincidently the grand finale of the Viking festival in York.”

The Five Most Important Things This Week

by Alan Hanson

Veterans Day

Double-dripped from generations above we Hansons were military men until Me With My Many Feelings destroyed the line. You see, Papa was a California dream-machine with brass curls but he flipped his coin for the US Army to save our family. His brother followed in double-time. Grandpa hugged missile silos in Alaska during Korea and there’s rumor someone before him rode rough with Ol’ Theodore. Both my mothers’ fathers were pilots and both died before the Internet — one in Vietnam, the other with cancerous lungs. And it’s knuckle-hard to disagree while beaming respect but that’s the blood they bought for me, to be whiny problematic conflicting dodging and downright dismissive to it all. It’s an honor to know these citizen soldiers, it’s a buzzing burn under my skin that cracks each cell into fractions, so much so that it feels like many lives are living within my own, many men burrowed into my being, many walkways unobstructed thanks to these quiet cauldrons I call Home.

Lily Allen

On Feminism, Sexism, Racism, Appropriation, and Cultural Symbols of Hip Hop: I am a straight white male. I am not qualified to comment on this nor have I anything substantial to contribute to the discussion.

On Websites, Music Writing, and the Thinkpiece Hydra: The oft-discussed problems inherent to writing on the Internet are many and ever evolving. Possibly my least favorite is the clamor to get a clip by any angle necessary. This nasty over-thinking and over-squeezing of any possible editorial idea is largely bred by the requirement of writing for free in the hungry, wailing infancy of one’s writing career, in tandem with the umpteen editorial outlets online believing they are required, nay, commanded by God, to say something if seemingly everyone else has. Believe you me, I am ecstatic that we have this wonderful, fantastical dreamscape of an Internet to amplify our voices. Hera wants clicks though, Hera wants trends and Hera prays for virality — thus the out-angling of each other for placement and bylines, thus a beast with poisoned-breath heads all licking around themselves; of the same body, sure, but each a malformed copy, ready to sprout two more warped versions of the same thing once a Hercules of Importance or Originality comes slicing it off at the neck.

Ghost Town 4 Sale

There is a brave, Schlitz drinking, Black Flag record clutching, middle-finger to All Institutions teenager thrashing around inside my chest and screaming, “quit yr fucking job, light your 401K on fire, and for Christ’s sake stop caring about The Future and Planning and Normalcy, you goddamn sellout, you piece of puke. You piece of puke!” And I dress in the morning with all of the shame, an amount of shame I am just barely capable of hoisting upon my slacked shoulders, ironing me down with sorry steam. He bucks and cranks at images of Montana, homesteads in Wyoming, and this week at an entire ghost town for sale on Craigslist. An entire town! A quiet camp for us to mute the city with, to cut the Want and Drive that pulls pounds from me each day. All the quiet I could hold. All the sitting to be done. The lust of labor. The communal dinners and the fires and oh, the stories! The stories so many. But it’s neon bullshit and cubical fantasy. And how that cuts. I live a whimper. That brave, angry teenager died years ago. I buried him with my credit score.

Andy Kaufman

Don’t end your script with the waking of a dream. Don’t believe in any ghosts that aren’t your own. Don’t crutch silly hopes of old ideas. And if so, so what? Let him stay, for all intents and purposes, dead as he wants. Don’t come back. Kill yr idols, rid yrself of worship, unfollow yr idols who are still living and tweeting. They’ll only disappoint you and muck the ideas that are now yours, so very yours. There’s nothing special about disappearing. There’s just nothing.

Swearin’, “Dust In The Gold Sack”

This perfect 90s-tinged distortion-mourn didn’t come out this week but I’ve played it thirty times a day. It’s too fitting for those blindingly bright days that crisp your cheeks, with your purpose pace and your coat zipped to the throat, that sun licked almost-winter. Allison Crutchfield’s earnest, sweet declarations of memory make me want to bed down in the crunchy guitar’s bent notes and hold onto all that’s leaving — not the most progressive or healthy strategy, but a comforting one all the same, and one that strikes you hard as you turn this song to full volume after speaking with your freshly stroked grandfather and you’re staring at a John Varvatos storefront on the Bowery.

Alan Hanson is a Californian writer living in Harlem.

Two Poems By David Lehman

by Mark Bibbins, Editor

Poem Ending with a Phrase from Federico Garcia Lorca

The last time I saw Lorenzo

he was wearing a blind man’s glasses

and holding the leash of a seeing-eye dog

though he isn’t blind

and he doesn’t have a dog

and his name isn’t Lorenzo but Bruce.

Who can explain why a man might dance

on the ledge outside his office

five flights above the Hudson River?

The city with five boroughs and two thousand bridges

fits on one side of the coin

my father gave me to give to a beggar.

It remains in my pocket as I look out the window

on the day of my old friend’s funeral,

and the stock exchange becomes a pyramid of dawns.

O my great river, treat me as you would a sailor!

I hear Harlem murmur through elevator shafts.

This is not hell. This is a fruit stand.

No one sleeps. Everyone dreams. And you, Walt Whitman,

bearded with butterflies, are eyed by virile comrades

pointing you out in bars: “He’s one, too.”

The Killer

The killer wants to go home with Steve

She looks great in tan pants on the Riviera

The killer helps the police solve the case

of the animal shelter queen

The killer went on a cruise with Steve

for their honeymoon but he got sunburned

and she had an affair with a married man

and came home alone.

The killer is not a serial murderer though he

has four of the five telltale signs.

The killer’s favorite singer is

The killer’s ordeal began in an alley with

two other drunken bums

The killer lets the phone ring.

The killer changed her lipstick from crimson to

something a little less overt.

The killer is wearing a short skirt.

The killer is a control freak.

The killer’s panty hose are in a twist.

The killer likes to say “carry on” as if she

were a Brit.

The killer is married to a twit.

The killer is a tigress riding on the back

of Steve’s motorcycle.

The killer has never been in this position before.

David Lehman’s New and Selected Poems is just out from Scribner.

You will find more poems here. You may contact the editor at poems@theawl.com.