New York City, June 28, 2017

★★★★★ It was chilly enough on the final walk to kindergarten for the five-year-old to complain about, but not enough for him to put on the hoodie that was in his backpack. Hardly any hours later, fighter jets tore over from south to north as the parents waited for the gates to open on the end of the half day. The now ex-kindergarteners adjourned to meet again in the Sheep Meadow, where it was not easy at first to find the others in the sunny vastness. Dragonflies flew low and the clover blossoms were spongy to walk on. The children sprinted over and over from the patch of shade where the parents were to an unsupervised patch of shade in the distance. For a while the five-year-old went barefoot, then he put his shoes and socks back on and abandoned his t-shirt. The children stayed after the sandwiches and the juice boxes were all gone, past the time that a full school day would have let out. There was nothing to stop the children from running and nothing they needed to rest up for.

The Joy of Reading About Reading About Cooking

Tejal Rao’s comfort books

Maybe I would have learned this reading anything, but I learned it reading cookbooks: Words can be used to make an idea more precise, or more vague, to make something clear or to blur its edges. Some writers are good at imagining people who don’t live a life exactly like their own, and others seem incapable.

The Joy of Reading About Cooking

Not for nothing, but “Skin the chicken. Tell me everything. Crush the garlic.” would be a perfect title for an essay collection about food.

Tchaikovsky Hated The '1812 Overture,' Which Sucks Because He Also Wrote It

This is the edition of this column that will come before the Fourth of July, and so I would like to present you with a piece you are almost certainly going to hear this weekend if you are an American reader and that is Tchaikovsky’s 1812 Overture. I know. I know. I wrote about Tchaikovsky only two weeks ago. Look, I’m well aware. And I didn’t intend for it to be this way, but it’s what I’m doing. If you want to read about something else, you can start Classical Music Hour with, I don’t know, Robert or whatever your name is, and be very happy. That’s fine.

We think of the 1812 Overture as this very American piece and we play it on the Fourth of July for whatever reason, which is just nutso for so many reasons. Last year, I watched a very grown man cry to this piece of music and I was like, “Are you sure?” Do you even know what it’s about? Have you just been assuming the 1812 Overture is about the American War of 1812. Guess what? It’s not!! I distinctly recall reading about the history of the 1812 Overture at the end of last year when I was reading my gigantic Tchaikovsky book (the Anthony Holden biography), and making a mental note to ruin everyone’s Fourth of July so here we fucking go.

In 1881, Tchaikovsky was commissioned by his old friend and mentor Nikolay Rubenstein to write a piece for an occasion commemorating a new church known as the Cathedral of Christ the Savior that had been commissioned to be built in 1812. So, I guess that’s how long it took back then to make a big cathedral. In addition, the piece also had to commemorate the silver jubilee of the Tsar (that’s 25 years). So, it was one of those classic “happy about a big church” + “congrats to the Tsar,” kill-two-birds-with-one-festive-overture-types of situations. But Tchaikovsky, who does not care about the church and does not care about the Tsar, bitches and moans and groans but eventually commits to the piece which he writes in one week, nearly four months after first being asked.

Tchaikovsky hated this piece!! He hated it so much. That’s nuts. We (Americans) love it. He thought music written for and to commemorate occasions was “banal with a lot of noise.” Honestly that’s true! When he finally turned it in, Tchaikovsky wrote: “I don’t think the piece has any serious merits, and I shan’t be the slightest bit surprised or offended if you find it unsuitable for concert performance.” AHHH. This is truly something he wrote for the paycheck. Truly, if he knew how often this piece is played now I think he would be livid.

The other thing to know is that the thing the Cathedral of Christ the Savior was commemorating (things in the past were always commemorating each other) was the Russian military defeat of Napoleon. This is why La Marseillaise (the French national anthem) comes in and out of the piece throughout but perhaps most notably at the 11:53 mark (this week we’re listening to the Chicago Symphony Orchestra’s 1996 version conducted by Daniel Barenboim), only to be totally, finally, and aggressively overtaken by the melody at the end, meant to represent the glory and strength of the Russian military anthem. I’m not saying we shouldn’t commemorate the strength of the Russian military every Fourth of July but it is kind of a [collar pull] these days, you know?

Which raises the question, how did this piece become so heavily associated with American culture anyway? The short answer is: pops orchestras. Arthur Fielder, of the Boston Pops, “the big Pops,” as we say (we don’t), added it to his 1974 televised Fourth of July special and everyone was like, “what the!!!!” and now it’s history. But hey. You can cry to it if it makes you feel good. It is a cool piece. It was in V For Vendetta! There are cannons! It is such a fun piece to listen to while sitting on a big picnic blanket and with a cannon and some berries and playing cards with your family and maybe there are fireworks too. What I’m trying to say is, you can kind of see why this is the sort of thing Tchaikovsky just absolutely fucking hated, which rules.

Fran Hoepfner is a writer from Chicago. You can find a corresponding playlist for all of the pieces discussed in this column here.

Costco Beers To Go With Your Costco Dad

A review of Kirkland Signature’s craft brews

Costco was founded by a dad, which isn’t surprising. Home to outrageously large quantities of things you don’t really need now but might need one day, it’s the ideal store for the sect of our society that considers knowing how to change a tire an essential part of a drive to the park. It’s also got great benefits, prioritizes the health and happiness of its employees, and maintains the lowest employee turnover rate in American retail — all things that America’s dads, when sitting us down to talk about jobs, seem to push for.

What Costco is not is cool. While Trader Joe’s caters to your cool aunt or mysteriously wealthy roommate with its ever-changing collection of just-because fun-time snacks, Costco understands the gravity of the situation of filling your house with food, in case of hunger or emergency. Usually housed in the sort of large-scale bunker many wholesale enthusiasts dream of building for themselves one day, the stores are fluorescently lit and arranged in what can only be described as “an honest set-up.” The entire Costco marketing scheme, it seems, is that the buyer slowly starts to say to himself, “why go anywhere else,” and that’s basically it.

This never-ending dungeon of convenience is, in my experience, most effective on dads, who love the idea of being prepared but hate the amount of stops they might have to make to pick up supplies for said preparation. With Costco, the entire apocalypse can be managed in one brief trip. Even daily life starts to look more and more efficient. My own dad, for example, discovered one day that Costco sold jeans, and later, after moving I assume just a little to the left, shirts too, and now purchases almost all of his clothes exclusively at Costco, which isn’t even an insult.

What makes the Costco brand special is its comfort. The Kirkland Signature brand, which makes everything from trail mix to roughly sixteen other types of trail mix, is unmatched in its ability to produce an exactly acceptable quality for what will eventually be, once you make it through the whole container of two dozen eggs and one gallon of soy sauce, an unbeatable price. There’s nothing particularly fancy about these products, but they do their job, and therein lies the dad-ness.

Kirkland’s Signature’s recent move into craft beers has been met with cheers from fathers across the nation who are interested in this sort of thing, sure, but aren’t driving out of the way for a chocolate stout. To better support those attempting to bond with their dads over a meeting of two generations’ most beloved inventions, I’ve matched six of Kirkland Signature’s best craft-brewed beers with the dad experience they most resemble. Please enjoy responsibly, as your dad would say, except he wouldn’t be joking when he said it, he’d be serious.

Kirkland Signature Craft Brewed Pale Ale. When your dad reads an article about an absolutely once-in-a-lifetime horrific accident that could almost never be repeated without a series of impossible circumstances falling directly into place and sends you the link in an otherwise empty email with the subject line “Be careful.”

Kirkland Signature Craft Brewed India Pale Ale. When your dad comes to visit the apartment that you’ve been living in a for a whole two years and takes a look around and then sits down on the sofa and just sort of remains there until it’s time to leave again except for a brief moment when he notices something about your kitchen cabinets that isn’t necessarily broken but could possibly function better so he sort of messes with that and maybe fixes it and then sits back down and checks the news on his phone until your mom’s done making sure you know you could have an old quilt she has at home that you never asked for, if you want it, which you don’t.

Kirkland Signature Craft Brewed Double Bock Beer. When your dad walks into the kitchen in a normal way on a normal day and starts putting together a snack so repulsive you wonder if he’s finally aged out of the part of his life where he can taste and see and smell things and then asks you if you want him to save you some even though it’s just mayonnaise and anchovies and a banana on a cracker, which should never be saved, not even once, and when he doesn’t still doesn’t register that what he’s eating is a crime in at least three different countries and one full continent starts to explain that he “came up” with this “sandwich” while your mother was out of town a few weeks ago, which was a boring weekend but ultimately worth it, because he got to invent this snack.

Kirkland Signature Craft Brewed Session IPA. When you’re out to dinner with your dad after you’ve finally turned not 21 but 22, which is the age where you start to appreciate wine, and are ready to impress him with your knowledge of saying things like “I’ll have the Pinot Noir,” but the restaurant doesn’t have a Pinot Noir, the one wine you know, so you have to wait for your dad to order his wine first and then pretend to look over the menu one more time and then say, “Actually I’ll have that too,” but it’s already too late, the waitress forgot, and you don’t know how to pronounce the word “Beaujolais” so your dad has to order it twice.

Kirkland Signature Craft Brewed Brown Ale. When your dad starts telling you a story about something he did when he was younger and you start to recognize little bits of it as parts of a story you have about something you did also, and the more he explains it the more you realize you both reacted the exact same way, except in maybe one minor detail, and that that detail is probably what separated the person your dad was before he became your dad from the person you ended up meeting, when you finally got around to being born, but you don’t really tell him any of this, you just say, “oh” and “ha” at the appropriate parts of the story.

Kirkland Signature Craft Brewed Kolsch German-style Ale. When you’re sitting in the same room as your dad and you want to listen to “Cut to the Feeling,” but feel like he probably doesn’t want to listen to “Cut to the Feeling,” so you just turn it on and say, “Here’s that song you wanted to hear,” and he waits a full forty seconds before saying “I don’t remember wanting to hear this.”

When my own dad saw me sitting with one of each of these six beers, which retail at $17.99 a case, open at once, he said “that seems like a waste” and asked no further questions.

A Poem by Mary Jo Bang

Fragment of a Bride

Mary Jo Bang is the author of eight books of poems and a translation of Dante’s Inferno. Her most recent book is A Doll for Throwing (Graywolf, 2017).

The Poetry Section is edited by Mark Bibbins.

Alex Cameron, "Candy May"

What was your favorite thing about last year?

In retrospect the best thing about 2016 was that it wasn’t 2017. Even the final two months of 2016, which seemed horrific at the time, were an idyllic era of joy and tranquility when compared to the base-level anxiety with which we now begin every day, a correlation which does not even take into consideration the rest of the day, when that anxiety is both corroborated and intensified before coffee. Another good thing about 2016 was Alex Cameron’s Jumping the Shark. His new album, Forced Witness, is out in September, and here’s the lead single. Enjoy.

New York City, June 27, 2017

★★★★ The cool, bright morning seemed continuous with the evening before, but the cars and sidewalks had been splashed down by a shower in between. An unpleasant pinkish gray grew in the west and lurked there for a while, and even when the full sunlight returned there was a murkiness to it. Citibikes were cutting through the crosswalks none too steadily. The air lost some of its stickiness through the hours, and a breeze ambled around. A cliff of cumulus fell in slow motion across the space between building facades. Reflected light got in among the steps of a fire escape. Gladiator sandals kept showing up. In the late west there was a shapeless golden glow like Zeus on the prowl. A bird, huge but far away, turned in the sky where the bright blur gave way to the ordinary gorgeousness of sharp silver and gray.

Eternity Itself

Instagramming in Venice

Maybe Venice wasn’t the best place to go in hopes of breaking, or at least calming somewhat, a debilitating Instagram addiction — Venice during the Biennale, no less. Even when not given over to oligarchs looking to launder money through merchandisable art, Venice is, on the face of it, well, all about face: art, artifice, surface. Three-hundred sixty-five days of the year, every year, Venice is the world capital of superficiality.

I mean that in a good way. No place is more beautiful, because no place has spent more time primping itself while staring into the reflection in the surrounding lagoon. No city has more of its collected wealth invested in its facades — facades qua facades. We need look no further, or deeper, than St. Mark’s Cathedral with its gold foil applique and marble tile siding for proof — needn’t and couldn’t, as there really isn’t a there there beneath the varnish and veneer; even its most stolid and sacred of buildings are but stucco and cement confections, done up like Liz Taylor.

In her great book on Venice, Mary McCarthy observed that, as garishly adorned as they were, the exteriors of the various palazzi in Venice appeared as nothing more than painted stage set flats. And the city does have the scale of a playhouse, a dollhouse diorama theatre. Every quiet little piazza, entered suddenly, alone, seems to be awaiting an errant troupe of Ren Faire players due back at any moment from their smoke break. And, like stage flats, every dusty pink wall, every terracotta-toned painting, every twisted Murano glass, and ornately patterned lace in Venice is constructed to communicate, to broadcast. Every Orient-inflected detail propels a narrative, like a souvenir, vouchsafing its owner’s character: I am this; I have been here and done that.

Instagram too is like a kind of stage set, beckoning performers, projection. On Instagram, you might say, we are playing ourselves. And, as in dream, or memory, these projections of ourselves needn’t be accurate to be true. In fact, it is in the elisions and exaggerations that we tell our truest stories. And like junkies, or expatriates, we seem to be opting out of the real life in favor of the fantasy. And Instagram addiction is not entirely unlike the distraction provided by the theatre either, a kind of half-stimulated, half-marveling fugue state: Entertain me, entertain me. What else, what else. When we are in its thrall, the feed walls us off from reflection, from secondary layers of consciousness. In the spring of 2017, all of the newly installed art on display, in the old arsenal depot and in the permanent pavilions clustered in and around wooded gardens (the “ Giardini”), built specifically for the purpose of the annually alternating art and architecture fairs, seemed made — staged? — to be Instagrammed.

On the road, away from home, we are allowed to believe ourselves to be the best versions of ourselves, our fantasy selves. More mindful, more attentive, interested, eager even, our traveling selves are who we might be if not for the debtors and responsibilities that dog us in our real life homes. The desirability of our traveled-to places, then, is in direct correlation to the ease with which it facilitates our dreaming, our ability to escape ourselves, the ease with which we can slip into the fantasy world of that place — a fictional construct of the city made up of all the cultural referents that most appeal to you (in the case of Venice, for me: Visconti, Nic Roeg, and Talented Mr. Ripley). And no place is more receptive to the projection of a past or a fantasy, no place more welcoming to the romantic than Venice, where we can easily still trace Casanova’s adventures, or walk in Aschenbach’s sandy footprints, searching for whatever it is that Tadzio means to us. Venice, more than any other place, feels like the surrealist reality of Escher’s dreams — so many staircase bridges leading you, somehow, back to where you started. There is an actual hedge maze, on one of Venice’s islands, and, fittingly, named for Borges. But the real labyrinth is the city itself, haphazardly set down first in refuge from the rampaging Attila, and to this day inexorably bound to malarial islands in a lagoon.

Venice is a city famous for doubling, twinning things — beginning with that Narcissisian reflection, and on to the twins in Don’t Look Now. But why, I wonder, when I visited in May did I feel the need, when in search of a new layer of experience, to reconnect with discoveries past — to again find solace in the relatively calm back garden of the hotel Metropole, for example, to insinuate myself again amidst the garrulousness of the off-duty gondoliers at Trattoria Rivetta? Retreading past visits, going back to places of great reverie doesn’t double the memory so much as it doubles the place (if only in my mind). A particular hotel garden, say, which my memory has already carried away and edited into usable shape for a story cannot possibly be the same one I enter again on the next trip — I’ve opened a new memory document, Metropole1. In order to orient myself, to weave new memories into a matrix with the places I’ve known before, I’ve obliterated a past, or at least, altered it, turned it into a shrine to itself. Like an Instagram post. Or, like Venice itself.

Henry James wrote in Italian Hours, that “Venice of today,” this, in 1909, “is a vast museum, where the little wicket that admits you is perpetually turning and creaking, and you march through the institution with a herd of fellow-gazers.” All true. It is a museum to itself; it is playing itself in the play that is life — and what could be better? What is more deserving of preservation and celebration than this weird exotic fairy tale confection of a city? “The sentimental tourist’s sole quarrel with his Venice,” James wrote, “is that he has too many competitors there. He likes to be alone; to be original; to have (to himself, at least) the air of making discoveries.” Every time I’m in Venice, I swear up and down that I am going to quit my present life to stay there and paint. (“Watercolors,” replied one ferry captain when I bored him with this fantasy, as though he’d heard it a million times before.) Whether or not it is yours alone, it’s impossible to not feel as personally possessed by the light in Venice as Turner so obviously was.

Though everyone in town that week was there, ostensibly, for the art, an exorbitant amount of time was spent posting, posing, staging, scrolling, and even talking about Instagram — just as you’d expect. Because image making — in the sense of sculpting one’s self-image, one’s public image, as well as the creation or capturing of an image — is at the center of our culture today. Maybe no one reads Playboy, or anything for that matter, for the articles anymore. Pictures are the artifacts and expression of the day. Which makes Instagram our sort of institutional memory, a nebulous, temporally vague cave painting of the culture.

The image, then, is the thing. While in Venice I began to wonder if it were the only thing — if Instagram were life, you might say, and the rest of our wanderings and doings, setting up the shot, primping in preparation for the performance, collecting and cultivation ourselves in readiness, would just be hashtag-behind-the-scenes.

The day I left Venice, my feeds swelled with pictures of the acqua alta then flooding St. Mark’s square — providing yet another reflective surface on which to contemplate Venice’s wonder, and, of course, providing another glorious photo op.

Your Phone Is Here To Give Your Mind A Rest

What are you using your brain for anyway?

Is your smartphone making you stupid?

A new study suggest the mere presence of a smartphone reduces a person’s cognitive ability…. Researchers believe the findings suggest that the mere presence of one’s smartphone reduces available cognitive capacity and impairs cognitive functioning, even though people feel they’re giving their full attention and focus to the task at hand.

On the one hand, oh no, you’re getting dumber. On the other hand, how smart are you now? How’s that working out for you? How much are you enjoying watching every stupid possibility become your constant stupid reality? How wonderful does it feel to be alive to the incredible idiocy that is life here in 2017? How helpful is your precious intelligence as you observe fatuity on a scale that would have been unimaginable even a year ago become not only commonplace but celebrated? How enjoyable is your awareness that it only gets worse from here, that every asinine thing you look down at now will at some point soon — some point very soon — seem like a work of genius by comparison? Wouldn’t you want to be one of the dumb people, so you can be amazed by all the astounding things that are happening all the time now? Wouldn’t you give anything to take away the pain that comes from your consistent comprehension of just how awful everything always is these days? If I were you I’d keep that smartphone with me at all times. I’d bring it into the bathroom with me. I’d put it under my pillow at night. I’d fall asleep to its soothing glow and wake to its friendly screen. I would make myself as dumb as I could as quickly as possible. And don’t kid yourself, it’s a race against reality to see who can get dumber faster. Put your smartphone inside you. It’s the only way. Phone help make better brain for you. Do now.

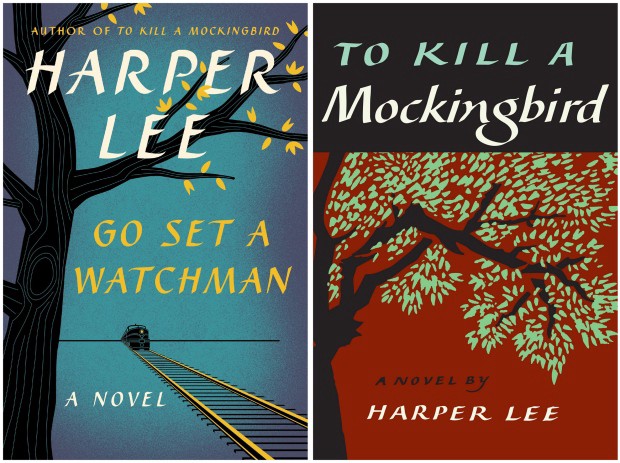

Jem Finch Has Been Dead the Whole Time

The family name is Scout’s to preserve.

After Harper Lee released the first chapter of Go Set a Watchman to The Guardian and The Wall Street Journal, Buzzfeed published a poll surveying readers about their responses to one of the most shocking revelations in the book: Jem’s death. The most popular response, garnering 58% of 14,660 votes, was, “I’m devastated. Jem was the ultimate big brother. Literally in tears right now while I cancel my preorder.” “I can’t believe it. I have tears in my eyes,” a commenter mourned in a Vulture article titled, “Let’s Talk About That Sentence in Go Set a Watchman.” Time’s Daniel D’Addario wrote, “One of the most important relationships in To Kill a Mockingbird is now effectively over; fans of To Kill a Mockingbird who’ve been hoping to return to Maycomb for decades will not revisit one of its most sensitive and complex residents.” When, nearing the end of our reading of To Kill a Mockingbird, I asked my class of 9th-graders whether or not anyone had read Go Set a Watchman, one student announced matter-of-factly, “Jem dies.” Other students gasped. Readers come to know Jem, or, more formally, Jeremy Atticus Finch, through Scout’s narration of her childhood, and our narrator’s clear attachment to her older brother is contagious.

But if you read the first page of To Kill A Mockingbird with close attention to the way Scout switches verb tenses, Jem’s death comes as no surprise at all. To the contrary, Jem is already dead by the time the novel begins. In the first paragraph of Mockingbird, Scout uses the past tense to recall that Jem broke his arm when he was thirteen and his body never truly recovered. She explains, “His left arm was somewhat shorter than his right; when he stood or walked, the back of his hand was at right angles to his body, his thumb parallel to his thigh.” Here, Scout explains how Jem’s accident permanently affected his body. In the next paragraph, she switches to the present tense and then back again when she says, “I maintain that the Ewells started it all, but Jem, who was four years my senior, said it started long before that.” Scout is alive to tell the tale — she “maintains” in the present tense. Meanwhile, Jem exists only in the past tense — by the time Scout tells the story, he is no longer four years Scout’s senior, and his left arm is no longer shorter than his right. Jem has been dead for as long as Scout has been telling the story of his broken arm.

What to do with this information? Maybe this reading of the first several lines will change the novel’s meaning for you. Maybe To Kill a Mockingbird is meant to be read as a Finch family history, written to memorialize Jem and to preserve Atticus’s legacy. When I suggested this interpretation — that To Kill a Mockingbird is a book about writing a book and recording history — to my freshmen, one student’s brow furrowed and he asked if Scout had any male cousins that shared her last name. After I confirmed that Dill and Francis bore different surnames, he explained his rationale for asking the question: if Jem is dead, the Finch name is Scout’s to preserve. My freshmen are sharp. Since Scout is a woman, and therefore likely to either marry and take her husband’s name or remain unwed and childless, writing a book about her family was a way to preserve the Finch name and its history. There are several more cousins of various generations littered throughout the novel — like Atticus’ cousin, Ike Finch — who may or may not have children, but the point remains that if Jem were dead, Scout would shoulder the responsibility of preserving the meaning of Atticus’ and Jem’s lives in particular.

Given Lee’s repeated references to national, local, and familial histories throughout Mockingbird, it would make sense to think of the book as a Finch family chronicle. Time and again, Atticus, Jem, and Scout grapple with what it means to preserve their roots. In the first chapter, Scout tells us that the story of Jem’s broken arm began with Andrew Jackson, because he was responsible for their ancestor Simon Finch’s settlement near Maycomb. Jackson also haunts a later chapter in which Maycomb has a town pageant celebrating its history. In another scene exemplary of Lee’s emphasis on historical consciousness, Aunt Alexandra has pressed Atticus “to talk to [Scout and Jem] about the family and what it’s meant to Maycomb County through the years, so you’ll have some idea of who you are, so you might be moved to behave accordingly.” Aunt Alexandra wants the kids to be prepared to assume the responsibilities of the class into which they were born.

When young Scout complains that she cannot remember “all of the things Finches are supposed to do,” Atticus tells her to forget the whole conversation. He is torn between maintaining tradition — preserving the Finch legacy — and inculcating his children with a sense of moral and social responsibility that reflects the challenges they face in Depression-era Maycomb. After recounting this episode, Scout brings us back with her into the present tense as she reflects, “I know now what he was trying to do, but Atticus was only a man. It takes a woman to do that kind of work.” She never says explicitly what this work was, but it has something to do with preserving the Finch name. Is this the kind of work that, in her father’s absence, our adult narrator understands herself to be doing? It’s certainly plausible. One of the book’s central concerns is the relationship between past and present, at national, local, and personal levels. This is to say that Scout, the story’s narrator, is in a constant state of remembrance, and perhaps mourning.

But even if Scout is recounting this story, does she think of herself as writing a book? How could we tell if Lee did endow her with this awareness of her enterprise? In a rare 1964 interview with Roy Newquist, Harper Lee said, “I would like to be the chronicler of something that I think is going down the drain very swiftly, and that is small town, middle-class southern life.” To Kill a Mockingbird is, indeed, a chronicle of a place like Monroeville, Lee’s hometown. Of course, Lee knew she was writing a book. And maybeerhaps she understood Scout as her stand-in. In the same interview, Lee said of her childhood, “I think that kind of life naturally produces more writers than, say, an environment like 82nd Street in New York. In small-town life and in rural life you know your neighbors. Not only do you know everything about your neighbors, but you know everything about them from the time they came to the country.” Lee’s interest in origin stories stems from her own upbringing.

It would make sense if Lee had thought of Scout as one of the writerly types so common to places like Maycomb. But Scout never acknowledges potential readers of or listeners to her story, as you might expect of a character with the awareness that he or she is writing. But in the same interview, Lee told Newquist, “Writing is the one form of art and endeavor that you cannot do for an audience. Painters paint, and their pictures go on the wall, musicians play, actors act for an audience, but I think writers write for themselves.” So maybe Scout writes for herself: to keep her brother alive in her own memory, and to remind herself of her heritage.

Books tie the Finch family together throughout the story, so writing one would be a fitting tribute. Throughout Scout’s childhood, Jem is constantly reading and recommending books to his kid sister. This delights her when they are younger but turns into a power struggle as they get older. In the second part of the novel, Scout recalls, “His maddening superiority was unbearable…He didn’t want to do anything but read and go off by himself. Still, everything he read he passed along to me, but with this difference: formerly, because he thought I’d like it; now, for my edification and instruction.” Even as Jem grows moody and Scout finds him intolerable, their bond through books changes to accommodate their new dynamic, but it does not disappear.

When Scout’s first grade teacher, Miss Caroline, asks when she learned to read, Scout reflects, “I could not remember when the lines above Atticus’s moving finger separated into words, but I had stared at them all the evenings in my memory, listening to the news of the day, Bills to Be Enacted into Laws, the diaries of Lorenzo Dow — anything Atticus happened to be reading when I crawled into his lap every night. Until I feared I would lose it, I never loved to read. One does not love breathing.”

Reading is at the center of the Finch family dynamic. When, at the very end of the novel, Jem lay in bed unconscious, injured by town antagonist Bob Ewell, Scout found Atticus reading one of her older brother’s books. When she asked why he was doing this, Atticus replied, “Honey, I don’t know. Just picked it up. One of the few things I haven’t read.” The novel ends with Atticus reading the book aloud to Scout. They are able to access some corner of his mind even though he cannot communicate. Maybe writing a book like Mockingbird is the best way Scout knows to pay tribute to her family.

Many of my students found Mockingbird’s last chapter boring. To be sure, not much happens on the level of plot. Atticus reads Scout to sleep from one of Jem’s books. These are the last lines of Mockingbird: “He turned out the light and went into Jem’s room. He would be there all night, and he would be there when Jem waked up in the morning.” Scout’s verb tenses are odd. It’s easy enough to pass them off as dialect. But what if “would” indicates contingency and possibility, and “waked” indicates an action that is complete? In other words, as the story draws to a close, if we think of Jem as eternally asleep, about to awaken, Scout’s parting words take on a tone of self-reassurance.

Try Googling, “Is Jem dead?” So many middle- and high-school students are panicked by the ending. We know, of course, from the first lines of the novel that he wakes up from this specific scare, but reading the book from end to beginning makes the last lines sound very much like Scout reminding herself about the time she thought she’d almost lost him but he’d pulled through. The book’s ending invites a rereading of its beginning, and in so doing keeps Jem’s memory constantly alive. The novel forms an endless loop of remembrance.

So maybe the book is about recording a family history. And maybe it’s not. When I asked my students whether or not they believed Jem was dead at the beginning of To Kill a Mockingbird, they almost unanimously agreed that the evidence was conclusive. When I asked them if it changed their interpretation of the story, their responses were less uniform. Mockingbird is strikingly multifaceted — it explores the intersections of broad societal issues like race, public education, class, gender, addiction, rape, justice, and what it means to grow up. About midway through the story, Calpurnia, the Finch family’s cook, advises young Scout, “It’s not necessary to tell all you know. It’s not ladylike — in the second place, folks don’t like to have somebody around knowin’ more than they do. It aggravates ‘em. You’re not gonna change any of them by talkin’ right, they’ve got to want to learn themselves, and when they don’t want to learn there’s nothing you can do but keep your mouth shut or talk their language.”

This advice is sexist, sure. But Calpurnia’s point — that it is not always best to make facts obvious to an unwilling audience, and that combative language is not always the best way to change someone’s mind — sums up a lot of what’s great about the novel. To Kill a Mockingbird is a secondary school classic because it starts conversations. Fans of To Kill a Mockingbird should consider that it is possible that the novel is about mourning Jem so that they can read it with all of the spiritedness it is meant to inspire.

Annie Abrams teaches and writes in NYC.