When There's Nothing Left To Burn, You Have To Set Your Work On Fire

Burn, Baby, Burn

As a young, aspiring artist (métier TBD) I was drawn, as many young, aspiring artists are, to grand acts of self-destruction. Because I was an angsty girl, most objects of my affection were also angsty girls: Sylvia Plath slipping into the crawl space of her mother’s house; drunk, bathrobe-clad Tuesday Weld on daytime television; Camille Claudel, seething over the specter of Rodin in the grim halls of the Asile de Montdevergues. You get the idea.

In an attempt to correct the folly of youth, I now go out of my way to avoid falling in love with masochism. I have a baby on the way, after all, and a pile of student loan debt and a thousand other reasons why sober steadiness might be my best path in life. But there is one practice that still sends my heart aflutter, and that is hearing of an artist who burnt his or her work.

In contrast to my previous paramours, the perpetrators of these acts of immolation are mostly male, according to my informally collected data, which makes me wonder if in the case of men, creating a work of art shouldn’t be compared to giving birth, as it is to the point of cliché, but instead to marriage, and the burning of a piece to the now-abolished Hindu practice of sati. (Fine, so in sati, a widow burns herself on the pyre, and of course a manuscript doesn’t have the agency of even browbeaten wife, let alone the limb motility, but as far as metaphors go, it’s decent at least.)

There are a few reasons this practice is so beguiling to me. First, all humans have a deep love-fear relationship with fire (see: Jerry Seinfeld’s astute observation that perhaps we love cigarettes so much because we consider it almost superhuman to be in control of a tiny, continuously burning flame.) I do enjoy hearing of writers and artists who destroyed their work in other ways — Monet stabbed and slashed many of his paintings, and Flaubert buried some of his personal papers in the ground, though it appears he always intended to dig up the trove later — but nothing is as romantic as fire, that multi-tongued beast, that melodramatic harridan. Second, the act of burning one’s work is deliciously anti-historical, and stands in stark contrast to the bulletproof posterity promoted by Facebook and Twitter and The Way Back Machine. It’s nigh impossible to imagine, in a world where a single politically incorrect Tweet can bring down a career, being able to truly erase an utterance, let alone a whole book.

But more than a big fuck you to history, the act is giant renunciation of the ego. It’s twisted Buddhism in that it proves that the writer isn’t attached to what we all assume must be most precious. Most of us are too afraid to allow a moment to pass undocumented, let alone vaporize years of toil, but the burn artist knows that both his life and his work are ultimately ashes. I imagine it must be a great sense of relief, to rid yourself of an unwieldy monument to your own ambition. If I were in the business of making puns, I’d call it an act of enlightenment. But I’m not nearly so corny. (In this same vein, I’ve often wondered about writers who go to great lengths to preserve their work. What does it say about theater critic Kenneth Tynan’s personality that he was so convinced his second wife would destroy his diaries that he left them to his children for safekeeping and, presumably, publication? What was it he felt the rest of us so urgently needed to see? Evidence of his urolagnia?)

If I had to give medals for manuscript burning, the top awards would go to Franz Kafka (obviously) and Nikolai Gogol. Even armchair Kafka enthusiasts know that while dying of tuberculosis, Kafka entrusted his work and assorted ephemera to his best pal Max Brod, stipulating that Brod burn it.

Dearest Max, my last request: Everything I leave behind me (in my bookcase, linen-cupboard, and my desk both at home and in the office, or anywhere else where anything may have got to and meets your eye), in the way of diaries, manuscripts, letters (my own and others’), sketches, and so on, to be burned unread.

Brod didn’t oblige. Though this is probably a heretical admission, I had always considered Kafka’s asking Brod to light the match a pussy move. (Or maybe it’s not that outrageous a reaction: Rivka Galchen, writing in the London Review of Books, said she, too, found Kafka’s last request “childish.”)

But Galchen and I misjudged Kafka, it would seem. Apparently he’d always been a burner. According to Rodger Kamenetz, author of Burnt Books: Rabbi Nachman of Bratslav and Franz Kafka, “Altogether, [Kafka] burned thirty-four hundred pages, or about 90 percent of everything he ever wrote.”[1] Kafka, it turns out, had been locked in a Sisyphean struggle of his own making his entire creative life, feverishly writing and then dropping the papers, still wet with ink, straight into the fire. His lover, Dora Diamant, who confessed to burning things on his behalf, said that for Kafka, burning his work was an act of “self-liberation.” “The element of fire,” Kamenetz posits, “is destructive and transformative.” One wonders if he didn’t, then, write as much for the product than for the sake of burning as an end to itself.

Gogol isn’t a less admired literary figure than Kafka, although his life has certainly not been documented with the same feverish enthusiasm as the latter’s has. In fact, the most recent comprehensive biography of Gogol was published in 1975 in French (unless you count a fascinating 1977 investigation into his love life entitled The Sexual Labyrinth of Nikolai Gogol, which is probably worth buying just so people can see it on your coffee table.)

But what’s important to know about Gogol’s literary auto da fe you can pick up through a cursory Google: on the evening of February 24, 1852, possibly going insane and also under the influence of a proto-Rasputin religious zealot, Gogol burned many of his papers, including a majority of the manuscript for what was intended to be part two of his masterpiece Dead Souls, which he had labored over for about a decade. After you let that sink in, read what Gogol wrote about the experience in a letter: “No sooner had the flames consumed the final pages of my book than its contents were suddenly resurrected in a purified and bright form, like a phoenix rising from the ashes, and I suddenly saw how chaotic was everything I had regarded as already having achieved order and harmony.”

From this description, it sounds like an incredible catharsis, or, in rock star-ese, a huge fucking rush. Curious, I decided that in order to have a last destructive hurrah before the birth of my child, after which I will certainly turn into a boring ur-domestic, I should engage in some targeted pyromania. For a second I wonder to myself if it isn’t a little disturbing that in my final days of freedom, I’m choosing to emulate Gogol instead of, say, someone with a sweeter reputation, like the protagonist of David Ives’s hilarious one-act play Degas, C’est Moi, who decides to become the famous ballerina lover for a day. Why be a Ukrainian hysteric when you can be lecherous Frenchman? But my mind has been made up, and Gogol it shall be.

First, I needed something worthy of burning. It had to be a piece of work I’d been mulling over for a long time — something of significant length, but not necessarily Dead Souls-long (ain’t nobody got time for that) and something not even the notes for which I had ever committed to Microsoft Word. Instinct told me that fiction was a better burnt offering than a well-crafted think piece, which was a bit disappointing for me as my fiction is uniformly maudlin and thus probably not much of a loss for anyone. There were, however, a few ideas that I’d had on file for a while, and so I picked one of the oldest, most beloved of that bunch, and forged ahead.

One very cramped hand and thirty-odd pages later, I completed what I was sure was a bona fide masterpiece. Or possibly a masterpiece. Eh, maybe just likely to be viewed by some, like my father and my pet cactus, as a masterpiece.[2] No matter. It isn’t the product being destroyed that gives the act its gravitas, but rather the act of destruction itself, I reasoned. After all, Gogol couldn’t have been sure he was writing his magnum opus when he was writing Dead Souls redux. The mere act of holding paper that I had written on with my very hand was novel; most often, of course, a work is just a tiny icon on a screen, and its destruction as easy as dragging said icon to the digital garbage (that is, of course, if you can be sure some other electronic copy isn’t languishing on an old USB drive somewhere).

Wee manuscript in tow, I gathered together the other necessary supplies: matches, small metal trashcan, and a container of lighter fluid, just in case. My kit was not terribly heavy, but, being nine months pregnant, I wasn’t exactly in the mood to schlep it far. Plus, I needed to find a location where I was unlikely to get arrested. As it happens, I live on a Notting Hill-style square in London, which affords me some privacy. To my disadvantage, though, is the fact that my neighbors are almost uniformly elderly and posh — the posted rules in the garden stipulate that we should avoid bringing bread products in, lest the crumbs attract the “wrong sort of birds,” which presumably are pigeons that didn’t follow the traditional Eton-Oxbridge path. If one of these stodgy local characters catches me with a miniature rubbish bin fire, I’ll certainly become the Square pariah.

Thankfully, no one is out and about when I arrive, despite it being a rare sunny afternoon. The weather doesn’t seem quite ideal for this activity — I feel it ought to be done in the still-dark morning hours, my face flushed from the heat rising off the Franklin stove, or maybe dusk in a clearing in a wood, the fruits of my labor meeting their demise in a bonfire threatening to break free of its enclosure any minute and swallow up the entire forest. The sun, the chirping well-bred birds, the freshly cut grass: it’s altogether too cheerful a day for an exorcism, but when I light the match and drop it into the bin, I feel my heart rate spike, and my soul clench and then growl. One by one, the edges of the pages curl, and the flames get larger, licking the side of the metal cylinder.

The whole thing takes probably ten minutes, but I’m mesmerized for every second of it. Mixed in with the high is a tinge of sadness. I had liked the story, actually. I had thought about it for ages before I determined it would be my literary sacrificial lamb. I suppose this is to be expected — maybe even Gerard Manley Hopkins wept over the poems he burnt before donning the frock — but there is no going back now.

Just as the fire is dying down, I hear the garden door clang shut, and see my ancient downstairs neighbor, who is literally a countess, being wheeled toward me by one of her aides. She looks mildly befuddled (which is British for “outraged”) and mumbles something that sounds like, “On a Sunday?” Careful not to grasp the still-searing bottom of the bucket, I surreptitiously dump the ashes of my masterpiece into the nearest bush and hightail it out of there. I scurry up the front steps of my building and then up to my apartment, slamming the door behind me. My husband has, in the interim, arrived home. He appears British-outraged; surveying his panting, wild-eyed wife, he sniffs the air before asking, “Why do you smell like matches?”

Gogol, c’est moi.

[1] Nachman of Bratslav was a Hasidic Jewish rebbe who routinely burnt his work in front of his devotees, simultaneously taunting them that the destroyed pages contained works of unimaginable mystic insight.

[2] For obvious reasons I cannot describe the plot here.

ẞ is for Nothing (SCHEIẞE!!!)

Deutschland über us.

While America was busy celebrating its 241st anniversary of independence from the British by committing a kick-ass new patriotic song to the canon (also maybe starting World War III), our no-longer-friends in Germany did not even have the chance to get us with any truly good burns about our sad state of affairs, because they were too busy reeling — reeling — from the latest attack on their traditional values.

No, I’m not talking about “marriage for all” (as Germans call it, and which was legalized in a parliamentary vote last Friday). What’s currently gripping Germany is even more controversial. I’m talking about a change that shakes the very notion of Germanness to its Kern. I’m talking, of course, about the new letter that was just officially added to the standard German alphabet.

That monstrous grapheme you see above is ẞ, the großes Eszett (GROSS-us ESS-tset), or capital ß, the letter best known to English-speakers worldwide as that big-B thing.

Yes, in its more ubiquitous form, ß does vaguely resemble a stylized upper-case Roman “B,” but you will have to trust me that it is pronounced like the double “s” sound at the end of English words like kiss and hiss.

The most famous appearance of the ß in the non-German-speaking world is in the word Scheiße (SHY-suh), or shit, which was made even more famous in 2011 when Lady Gaga used it as a song title, along with several bars of nonsense-gibberish-German on repeat that people kept asking me to “translate” for them.

To this day, if you try to Google that song, autocomplete offers Scheibe (SHY-buh), which means “slab.”

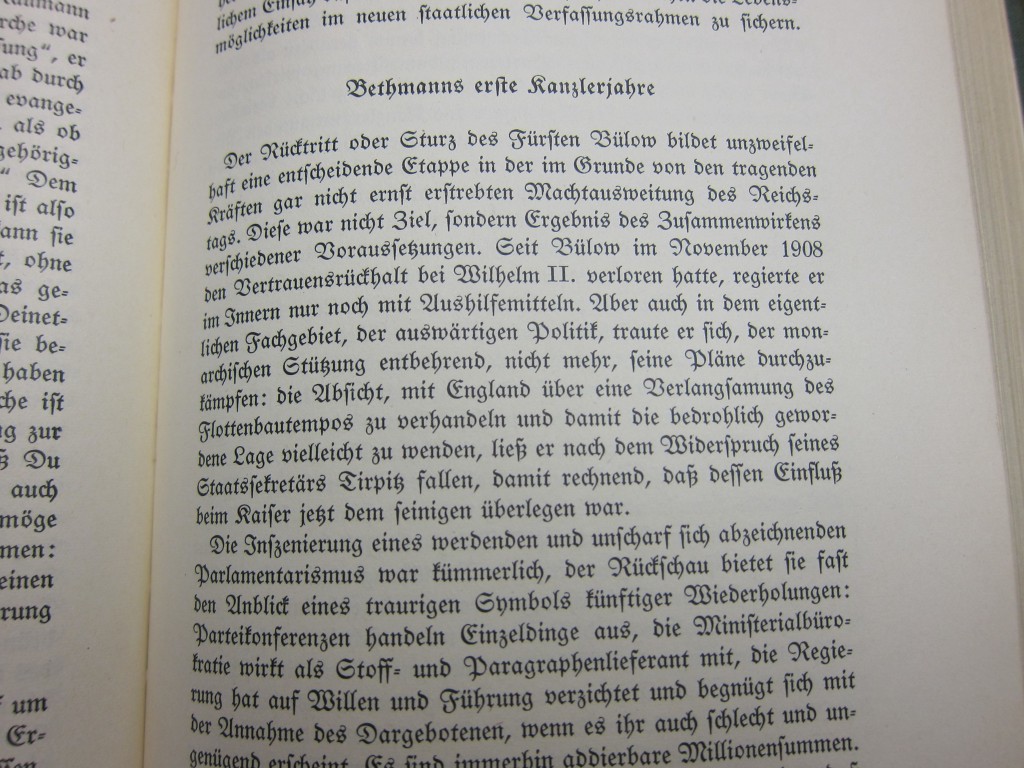

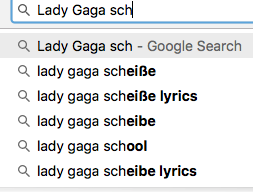

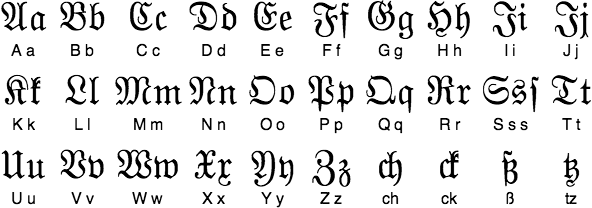

Though the ß is pronounced like a double s (and indeed, in Switzerland is replaced by one), the Eszett gets its name from the words for S and Z, and its unique shape from the way those letters used to look in the unholy German typeface known as Fraktur (frok-TOUR).

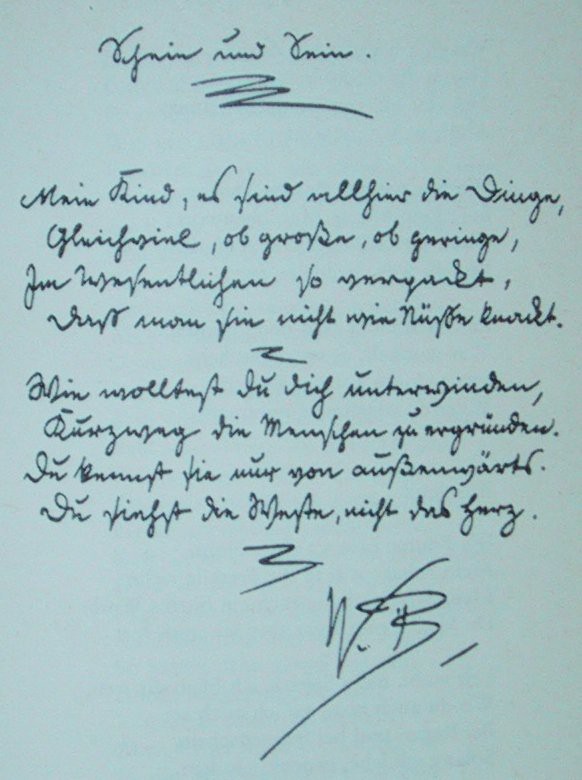

If you think that looks hard to read, by the way, check out what German cursive script used to look like:

Fraktur came into use in the sixteenth century, and most German documents set in type used it until the early twentieth. You may think of it as “the Nazi font,” but you’d only be half-right. At the beginning of the Third Reich, Hitler did prefer Fraktur, excoriating Latin fonts as the stuff of the Jew-run media — but then, in 1941, the NSDAP abruptly changed course, decided Fraktur was too Jewish after all, and banned it. (Some people think that this was actually a pragmatic choice; after Germany won the war and took over the world, it would be important for their decrees to be legible to all of their new subjects.)

Anyway, Fraktur had two versions of the small letter “s,” the one that looks a lot like that thing every middle schooler in 1996 covered everything with, which was used when an “s” ended a word. And then, there was the “s” used in the middle of a word, which looks way the fuck too much like a modern “f” and made for some interesting confusions in grad school, when I insisted it was “fine” to read assignments in Fraktur because “of course” I could do that:

When this second “s” appeared next to a Fraktur “z,” typesetters combined them into one character. And since the German “z” is pronounced like an English TS sound, putting one after an “s” in the middle or end of a word effectively created the sound of a sharp or double-S. (ME LOVE ORTHOGRAPHY but this is super-oversimplified, K? Don’t hate.)

Aaanyway, the long and short vowel of it is this: Because of the narrow circumstances of its birth, the ß is a character that a) is unique to the German language, and b) has never technically needed an officially-recognized capital version. UNTIL NOW.

Until last month, the German Council of Correct Spelling (the Rechtschreibrat, or WRECKED-shryb-rott, a thing that one hundred percent exists) didn’t see fit to include the “big ß” in the language’s voluminous official standard regulations. This is largely because the rules of German spelling dictate that the ß only appears at the end of a syllable.

The Logik would follow, then, that since one will never use it to begin a word, one will never need a big version in any official capacity. However, as this fascinating piece in the Süddetusche Zeitung points out — a newspaper that, by the way, printed an entire article about the capital ß without being able to print the letter itself, because they don’t have it standardized in their house font yet — there are actually times in which the ẞ is called for, aside from the extremely important work of writing SCHEIẞE.

Twitter poll for Germans: Before the ẞ entered official orthography, how did you spell “Scheiße” in all caps?

You see, on passports and in other official correspondence where names and other important words are in all caps, there needs to be a way to differentiate between a word that contains an ß and one that contains SS, since those are, technically, two different words. “People named Großmann and people named Grossmann won’t have to have their names spelled identically on their passports anymore,” explains the Süddeutsche, lending credence to my hypothesis that all people named Großmann and Grossmann are mortal enemies with each other.

So you’d think that this appeal to accuracy, in both naming and cursing (two things Germans hold dear), would be enough to universally welcome the ẞ. But you are wrong. For one thing, people hate the way it looks — hulking, pointy, bold-looking even when it’s not in boldface. “On a bend that’s as wide as a 1960s-issue streetlamp,” says the Süddeutsche, “dangles a violent hook, which looks like it could tip the whole thing over at a moment’s notice.” It is, in effect, “the SUV of letters.”

Add this, then, to the fact that the poor ß has had a tough go of it in recent decades. In 1996, Germany reformed its voluminous spelling rules to allegedly make it easier to follow them — and some 90 percent of those rule changes involved kicking the poor ß to the curb. (The other 10 percent involved removing commas, which gave undergraduate German majors all over the US license to never use a comma again, or, rather, to never start using one in the first place.) The biggest example of Verschlimmbessern (vur-SHLIMM-bess-urn, or making something worse by trying to make it better) was one particular result of the new rule that the ß could only be used after a long vowel or a dipthong.

Not only did this mean that in rare instances, a correctly spelled word could now have three S’s in a row — Flussschifffahrt, or “river boat trip,” which also contains three F’s in a row — but, as the Süddeutsche points out, the much-maligned difference between the subordinating conjunction that used to be spelled daß, which means “that” (as in, I know that you are not as good at German as you think you are), and the pronoun das, which also means “that” (but as in, Bring me the book that’s over there on the table that explains the rules of German correctly) was not simplified in the least. Under the new rules involving short stressed vowels, the conjunction became dass, but it still means “that,” and it still sounds exactly like the other das, which STILL MEANS “THAT.”

You know what? DAS IST TOTAL SCHEIẞE!!!!!

It is precisely these charming orthographic disputes that surely brought the novelist John Le Carré to his lifelong passion for German, which he condensed into a recent and elegant hagiography in the Guardian, one that urges us all to learn the dulcet vernacular of Heine and Hölderlin.

The latter poet, by the way, spent the final 36 years of his life in the throes of mental illness, having locked himself up in a tower on the banks of the Neckar river in 1806. There was plenty in Germany that was less humane back then (including the diagnosis of schizophrenics as “incurable”), but still: As Hölderlin gazed, in his anguish, at a boat as it floated past, the word that described its path was still spelled a far more reasonable way, Flußschiffahrt — and what’s more, there was not a hulking, tipping ẞ anywhere in sight.

Is Jonathan Cheban The Schlemiel of Calabasas?

Fame, fries, and vanity on social media

On top of a hill overlooking the San Fernando Valley, Queen Kris lived with her five beloved princesses in a gated shtetl called Calabasas. The shtetl was filled with happy, cheerful folk who lacked any worries other than reconciling their love of spray tans with their need for chemical peels. Each day, the sun rose with roosters crowing over the Malibu horizon and set with the loud splash of Instagram models diving into infinity pools. All was well in the shtetl until one day, Kim, Kris’s favorite princess, decided to bring home her new BFF, Jonathan Cheban. He descended from a shtetl far, far away in New Jersey. “He’s so funny, mom!” Kim called her mother and sisters downstairs to introduce them to her new companion. He had pasty tan skin, a bowl-cut, and was ambiguously aged. Little did they know that they were welcoming the schlemiel of Calabasas into their palace.

A famous Yiddish idiom states, “If a schlemiel decided to sell candles, the sun would never set.” In Yiddish folklore, the schlemiel is a farcical figure, clumsily stumbling into absurd situations because of his naïveté. In one tale about a schlemiel, a traveler driving a wagon picks up a peddler carrying a heavy sack. During the ride to the village, the driver asks the peddler why he doesn’t place the sack in the back of the wagon. The peddler replies, “It’s enough that you’re taking me to the city — you don’t have to carry my sack too!”

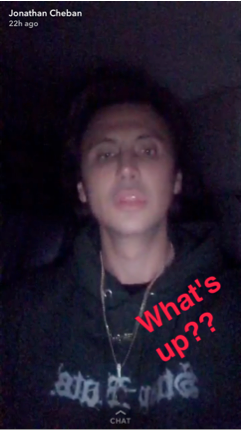

Jonathan Cheban, a 43-year old man who refers to himself as the “Foodgōd,” is something of an anomaly in the Kardashian-Jenner universe. Over the course of “Keeping Up With the Kardashians,” he has randomly appeared throughout the series, supporting his best friend Kim during times of need, soaking up all the attention at a tomato farm in Iceland, bragging about his impeccable PR wisdom while sitting poolside with Kendall Jenner, and — his favorite thing to do — snapping selfies with expensive food. His motivations and origins are unclear. In what nightclub did he befriend Kim Kardashian? What does he exactly do? Why is he so obsessed with food? On a TV show filled with people whose fame has been tirelessly debated, Jonathan Cheban illuminates the Kafka-esque shallowness of his surroundings in a highly specific way.

Before he was a Foodgōd, he was a publicist in New York City, working with Sean “Diddy” Combs and other celebrities in the early 2000s. At some point between the invasion of Iraq and the fall of Lehman Brothers, Jonathan Cheban met Kim Kardashian and became a reoccurring guest on her reality show. After a decade of standing in awe of his BFF’s success, he’s taken a stab at self-branding. Mr. Cheban spends his days documenting his excessive eating habits on SnapChat, Twitter, and Instagram. A typical day begins with gold-flaked Eggs Benedict for breakfast, followed by a lunch of albacore sashimi, a strategically lowbrow afternoon snack of French fries, dinner at an expensive steakhouse, and then the grand finale — an elaborate, pyro-technically enhanced cupcake topped with butterscotch caramel and Captain Crunch cereal. His quivering voice offers a rare window into a fraught subjectivity — “you guys…what’s up… you won’t believe this… a cupcake that lights up… and tastes like…cereal… you guys, this is HAPPENING! You guys…”

In Ruth Wisse’s book The Schlemiel as a Modern Hero, she argues that the schlemiel is “a fool, out of step with the actual march of events. Yet the impulse of the joke, and of schlemiel literature in general, is to use the comical stance as a stage from which to challenge the political and philosophical status quo.” Through his clumsy attempt at self-branding, Cheban manages to expose and subsequently mock the “status quo” of his star-fucker universe. Like other Instagram celebrities, his posts are peppered with sketchy product sponsorships and promotion deals. With Jonathan Cheban, however, everything seems laughably, hyperbolically fake. When scrolling through his Instagram feed or watching his Snap stories, rather than feeling hungry, jealous, or a combination of the two, one feels desensitized — more steak, more cupcakes, more 1Oak, more Miami Beach.

Though Kim Kardashian has mastered the art of social media-fame, Jonathan Cheban seems blissfully unaware that the secret behind his friend’s success is that she gestures towards being relatable. Her Instagram intersperses photos of her children with luxurious moments in private jets, embodying a 21st century motherhood that’s unattainable and yet seems achievable. After falling victim to a robbery in Paris, she took a break from social media altogether and then returned with a more refined, simplified aesthetic coupled with a renewed focus on her nuclear family.

While Kim occasionally gifts the masses a few breadcrumbs of authenticity — a tweet about how her son Saint West resembles the baby emoji, a lo-fi family video, and late night confessions of her psoriasis — the Foodgōd tosses us a self-combusting lava-cake for the umpteenth time. At its core, the Foodgōd brand is a vessel of excess lacking intimacy or narrative. Similar to his schlemiel forefathers, the moment he tries to sell candles, the sun decides not to set.

In spite of all the wealth and proximity to fame, Cheban’s schlemiel tendencies always radiate through, showing how unlike a gold-flaked sugary pastry, a fool can’t be repackaged with a shiny aesthetic. Yiddish scholars Irving Howe and Eliezer Greenberg, however, had insisted that readers treat the schlemiel charitably, describing him as having a “halo of comic sadness” whose “foolishness innocence triumphs over the wisdom of the world.” Although the Kardashians are successful at self-branding, there’s something oddly charming and endearing about Cheban’s shallowness — he’s either tragically oblivious or a self-aware genius. His awkward attempt at fame manages to triumph and expose the fallacy of social-media star “wisdom.” As Kim and her family conquer the world, Jonathan Cheban is tripping and falling behind them, bringing down the curtains and then turning off all the smoke and mirrors — a vanity that is powerfully poignant and revealing.

The schlemiel of Calabasas chips away at the princess’s kingdom one unicorn donut selfie at a time.

Kassiel, "West Hills"

Please don’t make me do this again.

There is nothing that makes you realize more just how horrible the Internet is than opening it up after a few days away. “Oh, right,” you think, “I forgot about how the Internet scrapes out my eyeballs, fills the sockets with shit, rubs salt around the rim for extra sting, covers them over with concrete and sets the whole thing on fire, repeatedly and without end, and then all my friends send me links just in case I missed any of it.” Anyway, back to work! Here’s some music. Enjoy.

This 4th of July Celebrate Yourself, Not America

And other answers to questions you didn’t ask

“I don’t really feel like celebrating America this year. What should I do this 4th of July?” — Not Patriotic Pat

No one ever said being an American was easy. And, perhaps, with some of our mythology stripped away by the current Administration, we can start to see what we truly are in this moment. For so long we’ve glanced over our own problems as a nation. It’s easy to get wrapped up in the idea that we’re a great country filled with great people. We definitely can be that kind of country. Even if we’re falling short of the promise at the moment.

For even if we never individually desired to become “The Ugly American” we certainly are collectively that just now. Elections do have consequences and one consequence of this last one is that we’ve seen how the American Electoral Sausage gets made. With hideous amounts of bluster, racism, sexism, hook and crook. Isn’t it better to see the gears of our democracy at their most gummed-up, to help you appreciate when some of our systems do function? The Washington Post, New York Times and Wall Street Journal have done Pulitzer-worthy work. The court system seems to be rolling along, even if Congress seems paralyzed by a dysfunctional Executive Branch. We haven’t blown up the Earth yet. So far, so good.

As amusing as it might be to imagine that the 25th Amendment might save us from this Trump Presidency, you’d have to reasonably expect lots of people who will never act responsibly to suddenly wish to do so. The same people who want to take health care away from poor people so that rich people can get a massive tax cut do not seem well-suited for the role of “adults in the room.” Trump is noxious. So are his followers. Better to let them be whittled down to squeaking gerbils over years of unabated do-nothing nonsense. There is no amendment to the Constitution to just let time do what it will. Just let it happen. With a little luck, the world won’t be blown up in the process.

But the USA has never been that great of a place. It started off pretty great. Except for slavery. At least it sounded pretty great on paper. But we’ve failed over and over again to live up to our collective promise. We’ve always talked a good game. And we’re great at joining World Wars toward the end. And we do a pretty good job apologizing for the shit we do afterwards. But the greatness of America has been mostly imagined. If you say you are great enough, if you win enough wars in the last year, if start to believe your own hype, you too can be “the greatest nation in the world.” Offering health care to all your citizens is not required.

This 4th of July isn’t about the USA, it’s about you. How are you doing? You’ve been through a lot this year with the election and the election results and now morons everywhere feeling empowered. This too shall pass. But right now, you deserve a day. Americans everywhere are generally decent people who imagine themselves to be fair-minded. They deserve a holiday for putting up with a year’s-worth of bullshit. And so do you.

Do not celebrate America this 4th of July. Celebrate Americans. They’re an optimistic and hopeful bunch who have their hearts in the right place even sometimes when they’re being sexist and racist. The shine may be off our democratic experiment with representational government. Big businesses and the rich have unfair sway into all of our systems. We may be 50 years past the point where we should have had another revolution, but for some reason we’re all still futilely trying to live with one another. And that seems like a cause for celebration! We’re too chicken to live apart. If there was a manifest destiny, it has turned into an inertia. We’re all stuck with each other. And that seems reason enough to celebrate. Unless you live in New Jersey, like me, where we’re even more fucked up than the rest of the country. Our state government is shut down for no good reason, and all the state beaches are closed! USA! USA!

As we celebrate this 4th of July, remember the sacrifices that got us to this point. We have basically given away all semblance of privacy because we’re scared of sporadic and not-very-successful terrorist attacks. We’ve abandoned our duty to vote because we know there are no real choices that will afford us lasting change. We hang on tightly to political parties who will argue both sides of an argument whenever it suits them. We underfund education, have trashed the planet and are greedy as fuck. Better luck next year.

Most importantly, don’t kill yourself with fireworks this 4th of July. That’s never a good look.

Jim Behrle lives in Jersey City, NJ and works at a bookstore.

New York City, June 29, 2017

★★★★ The heat had risen to a low but definite swelter. The midday breeze moved like the pleasant breezes of the days before, but it brought no comfort. A man flopped back in his seat and pressed a folded newspaper against his face. The bad smells were merging together into one bad smell. Past the peak of midday, though, the thickening filter of clouds overhead and the relentlessness of the air conditioning had combined to make outdoors more bearable than indoors, the warmth softening into something not just tolerable but easy. Artwork flapped up and down at vendors’ tables. The Krishnas were jangling furiously and a PA was blasting “Blitzkrieg Bop,” surrounded by signs and canopies meant to encourage people to have the identified experience of enjoying Union Square. Away from the effort, the benches were lined with people all along the pathway. A man coaxed pigeons onto his hands.

When The Video Plays You

Stop calling glorified powerpoints and two-minute summaries “video”

Print is dead. Editors are being laid off. And everyone who’s anyone in media is “pivoting to video.” But video is a lie!!!! Listen up.

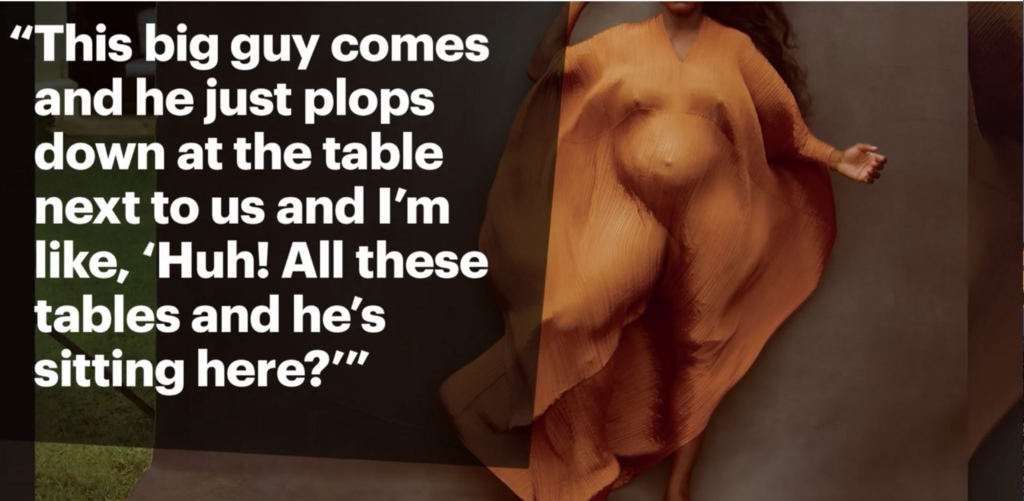

What these people are talking about isn’t even actual traditional worthwhile video. It’s a box with a play button on it just begging you for a click. It’s a glorified powerpoint presentation—slides, essentially, with words and pictures that flash and Ken Burns around the screen, sometimes with a shaded overlay. Consider this “video” that accompanied Vanity Fair’s cover story about Serena Williams’s romance with Alexis Ohanian:

Cover Story: Serena Williams’s Love Match

It’s literally just some still Annie Leibovitz photographs with Serena’s head cut off and some giant text—pull quotes from within the story that you are not reading because you are now watching this video—over it. What the hell? It’s just a bunch of animated pull quotes!!!!!!!!!!! How can you have a VIDEO about THE BEST ATHLETE ON EARTH and not have video footage of her just owning everyone up down and across every tennis court on earth? Why would you do that when you can just have anodyne stills that do a slow zoom?

Will people click this video online, say, on Facebook, where they won’t have to read the article through Instant Articles (hahaha remember Instant Articles), and they can just be satisfied with this summary? Sure!

Okay, how about a prestige newspaper like the Washington Post? A few weeks ago though honestly it seems like an eternity, the Post’s Adam Entous reported on GOP leaders speculating (humorously, but still) about Trump being paid off by Russians, “according to a recording of the June 15, 2016, exchange, which was listened to and verified by The Washington Post.”

Now maybe it’s just me, but if you drop a huge news bomb on me and say you got access to the recording, I’m probably expecting to hear it play when I press a multimedia button. But nope, what did I get instead? Adam Entous as a talking head, reading me a bedtime story. Just kidding, he was summarizing the news article he wrote in a nice, sharable, snackable two minutes and twenty-seven seconds. (It does not go unnoted that the video is embeddable here—always be sharing!—but I shan’t because I know you know how to click.)

These are the equivalent of Buzzfeed Tasty videos, but for news, and just like Tasty videos, it’s not a move into the “food” space so much as it is a content play. Likewise, these videos are not about “news” or even “stories” as much as they are pink-slime content nuggets. There is no nutritional value in most of the videos that advertisers are paying for these days. That’s not to say there aren’t people out there making videos of substance—indeed, video done well is an incredibly expensive, time-consuming, and laborious process. (Topic, for one, is aiming to create actual visual storytelling, not just empty-calorie animations.) Unfortunately most of these videos are following the model of the most successful viral feel-good videos.

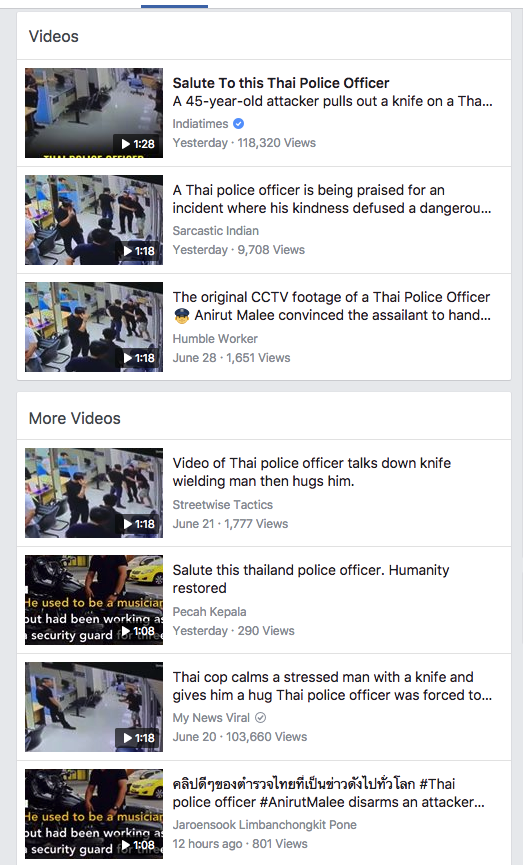

Consider one I saw this morning in my Facebook feed: A knife-wielding man in the Bangkok airport is talked down by a security guard, who then gives him a big hug as he breaks down crying, presumably from stress. The Daily Mail renders the story in a classic pre-video powerpoint bullet-point style—the entire story is above the dateline.

The Daily Mail linked to the CCTV video, posted online. From there, the video was spun off into any number of viral videos by various news outlets and content farms, with Upworthy-like headlines, with slow and meaningful-yet-urgent-sounding music, white and yellow block letters recapping the amazing, unbelievable, gotta-see-it-to-believe-it story:

Maybe to you this qualifies as a video because at the base of it is security camera footage. But to me, this is a cross between the shitpic and a John Oliver video. A digital copy of some image, either moving or still, then widely distributed for everyone to watermark and overlay and earn some of the likes and shares from. The videos these content companies are making now are just proprietary shitvids.

So yeah, the whole pivot to video thing is distressing because a) these are NOT videos, and b) the hype about videos is completely manufactured, just like the videos. As a wise man once vehemently blogged, everything is lies.

Odd Lots: Curious Objects Up At Auction

Queen Victoria’s crotch-less undies, Einstein’s pipe, and a decorative whale tooth

Lot 1: The Queen’s Unmentionables

Fancy a pair of royal underwear? The time is nigh. On July 11, a plus-sized pair of white cotton bloomers monogrammed on the waistband with the initials “VR” (Victoria Regina) below a crown, will be granted to the highest bidder.

Known as ‘split-drawers,’ these open-crotch panties literally split down the middle so that nice Victorian ladies didn’t have to remove layers of frilly clothing in order to squat over the chamber pot. As Therese Oneill writes in her hilarious book, Unmentionable, “This is why your dainty bits aren’t covered. Because even though no one in Victorian society will admit to it, a lady has to pee, and ‘closed drawers,’ as they will eventually come to be known … make that practically impossible for a fully dressed lady.”

Just about annually for the past few years, a pair of Vic’s knickers have appeared at auction; in 2015, a record-breaking pair sold for more than $20,000. The estimate for these, with matching chemise, and “some spots of discoloration” is $6,500–9,000.

Lot 2: Yes, the Genius Smoked

“I believe that pipe smoking contributes to a somewhat calm and objective judgment in all human affairs,” said the most brilliant man of the twentieth century. It’s true, Albert Einstein loved to smoke and was often pictured with a pipe in his mouth. Even after his doctor insisted that he give it up, he continued to chew on pipes regularly.

Nevertheless, the slightly gnawed briarwood pipe slated for auction in London on July 12 is a rarity. According to Roger Sherman, associate curator at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History, where another of Einstein’s pipes — also chewed — remains an enormously popular exhibit, the physicist “did not value material possessions,” making Einstein artifacts hard to come by, particularly very personal objects like a used pipe. It’ll take about $10,000 to acquire this one.

Lot 3: Lady Liberty is Scrimshawed

’Tis the art of sailors & whalers: scrimshaw. These are carvings and engravings done on bone and ivory, or, as in this case, whale teeth. Long hours at sea meant lots of time for arts and crafts. The preferred imagery to reproduce on their medium of choice was patriotic, literary, or political, and often copied from illustrations in whatever newspapers and magazines were lying around.

This mid-nineteenth-century example, valued at $500–800 and headed to auction in Edinburgh on July 5, presents two views: the female figure of Liberty with a star-spangled shield, likely originating from the newspaper Gleason’s Weekly Line-of-Battle Ship, according to the auctioneer; and a fashionista with a riding whip, as pictured in Harper’s New Monthly Magazine in 1858, under the heading ‘Equestrian Costume.’ Hold it up to your ear, you might hear the ocean. Or Lady Liberty bawling.

Rebecca Rego Barry is the author of Rare Books Uncovered: True Stories of Fantastic Finds in Unlikely Places.

Trump's Tabloid Ties

Required reading on the president’s cozy relationship with The National Enquirer

One employee said that Trump was also a frequent source for Enquirer stories. “When there was something going on in New York, David would talk with Trump about it. Trump provided David with stories directly,” the employee said. “And, if Donald didn’t want a story to run, it wouldn’t run. You can put that in stone.” Indeed, early in the 2016 campaign Pecker simply turned over the pages of the Enquirer to Trump, allowing the candidate to write columns under his own byline.

Now that I’m a civilian, two whole weeks will pass where I won’t read a single story from the latest New Yorker magazine. Here’s one I just revisited that you probably still have on your coffee table: Jeff Toobin on Donald Trump’s good friend and chief executive of American Media, Inc., David Pecker. The piece is newly relevant this morning as we enter Day Two of the Mika and Joe media-controversy-slash-Twitter-feud with the president (Mike and Joe are now claiming they were blackmailed by Trump). The ironies here regarding “fake news” are so thick you could braid them (Guess who exerts control over stories! Guess where AMI’s board meetings are held!), but suffice it to say that Pecker has been openly eyeing Time Inc. for some time now, which should raise the eyebrows of anyone who still works there and is not exactly itching to serve the interests of the Trump administration.

The National Enquirer doesn’t have many subscribers or advertisers at all, and most of its sales come from checkout lines at grocery stores, especially chains like Walmart and Krogers. Pecker is a rigorous student of sales data, and he knows that what sells is not investigations, but rumors and misleading statements—that gray area right before libel that comprises most tabloids’ bread and butter. As Toobin writes, the founding philosophy of the Enquirer, apocryphal though it may be, was to capture the attention of the rubberneckers:

As Pope later told the tale, he had an epiphany one day when he found himself gazing at a particularly gruesome traffic accident, and noticed how many other people had also stopped to stare. “It suddenly hit me,” Pope recalled. “That’s what people want to see. That’s what I’ll give them, blood and gore.”

When it comes to stories, Trump is sort of a one-man tabloid—he’ll advance anything, whether it’s theory or rumor or outright lie, because he knows it will sell.

I was always under the impression that the word tabloid came from the word “tablet” meaning a slab bearing some inscription plus the Greek suffix “oid” meaning “having the form or likeness,” and referred to the physical from of a printed broadsheet, but I was wrong. It comes (via trademark) from the word tablet meaning pill or drug:

Originally the proprietary name of a medicine sold in tablets, the term came to denote any small medicinal tablet; the current sense reflects the notion of “concentrated, easily assimilable.”

Houston, we have more drug problems than we thought.

St. Vincent, "New York"

I don’t want to go away, I just want everyone else to.

I’d like to think the days off will last as long as the days on do now but we all know life isn’t that sweet. Anyway, enjoy.