Wedgie Fatal

Ugh, America, I think I’d rather read another round of opinions on whether “Girls” accurately represents the struggle and ambivalence of the women at its center or if it is actually a slightly highbrow attempt at the titillation of 50-year-old men with HBO subscriptions and the sense that they are missing out on things than hear about this. I mean, assuming those are the only options at this point.

Tongues Wagged

“When even despair ceases to serve any creative purpose, then surely we are justified in suicide,” averred the critic Cyril Connolly. “For what better grounds for suicide can there be than to go on making the same series of false moves which invariably lead to the same disaster and to repeat a pattern without knowing why it is false or wherein lies the flaw? And yet to perceive that in ourselves revolves a cycle of activity which is certain to end in paralysis of the will, desertion, panic and despair — always to go on loving those who have ceased to love us, and who have quite lost all resemblance to the selves who we loved! Suicide is infectious; what if the agonies which suicide endure before they are driven to take their own life, the emotion of ‘all is lost’ — are infectious too?” On the other hand, the pop singer Taylor Swift and Snapchat CEO Evan Spiegel are rumored to have totally made out, so who’s to say?

What Happened To The Jobs?

Why is the unemployment rate staying relatively level (actually, a little bit “down”) at 6.7%? That’s because there is a shrinking pool of people who consider themselves workers. Almost 100 million Americans aren’t in the workforce.

People Not In Labor Force Soar To Record 91.8 Million; Participation Rate Plunges To 1978 Levels http://t.co/pgrHr9k1SR

— zerohedge (@zerohedge) January 10, 2014

And who’s in the labor force but not working? Well, one way to slice that is by education level. (You can also slice it by race, which provides equally disturbing numbers.)

Unemployment by education: No HS diploma (9.8%), high school graduates (7.1%), some college (6.1%), college or more (3.3%)

— Zachary Goldfarb (@Goldfarb) January 10, 2014

That whole long-term unemployment benefit kerfuffle ended badly, which is a shame.

Average duration of unemployment is 37.1 wks. Good thing there are emergency benefi…oh wait, no…

— Duke (@DukeStJournal) January 10, 2014

New jobs are in low-paying fields — and those low-paying fields are ever-more-low-paying (in particular, “leisure, hospitality and retail”).

#BLS In the largest category in which jobs WERE created (Retail +55K) wages DECLINED by 6 cents and hour from $14.14 to 14.08/hr #Deflation

— Dan Alpert (@DanielAlpert) January 10, 2014

And workers have less full-time work.

The average work week edged down to 34.4 hours in December. More highlights from the jobs report: http://t.co/nwJhEwSfXr

— Wall Street Journal (@WSJ) January 10, 2014

This makes people nervous.

Dec NFP: What cannot be ignored is the slowing in avg hourly wages to 1.8% Y/Y. It’s not sufficient to support spending at recent levels.

— Joseph Brusuelas (@joebrusuelas) January 10, 2014

Meanwhile, a big chunk of the labor force is aging out.

Only 62.8% of U.S. adult population participating in labor market — matching lowest level since 1978. http://t.co/Fv64X6HPls

— CNN Breaking News (@cnnbrk) January 10, 2014

All The Drunk Dudes: The Parodic Manliness Of The Alcoholic Writer

by David Burr Gerrard

It’s difficult not to romanticize a link between writing and drinking. Wisdom hurts, so the more wisdom a writer has, the harder the writer will try to drown it with alcohol. Or maybe it isn’t wisdom that needs to be drowned; it’s the inner editor. Or maybe the great passion that leads to great writing also leads to great drinking. Or maybe… anyway, there must be some connection, so can we please put down our horrible manuscripts and pour ourselves some bourbon already?

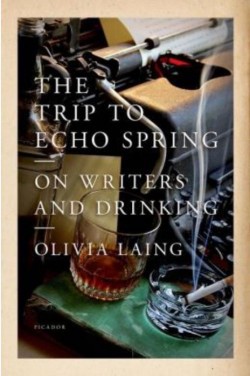

There is no romanticizing in The Trip to Echo Spring, British journalist Olivia Laing’s new group biography of six alcoholic writers — Ernest Hemingway, F. Scott Fitzgerald, Tennessee Williams, John Cheever, John Berryman, and Raymond Carver. There is also no demonizing, even when demonizing might be warranted. Taking the form of a travelogue and incorporating Laing’s own family history, The Trip to Echo Spring takes aim at the evasions and delusions of these men (and they are all men), but does so in a way that somehow increases our understanding of and admiration for their work.

Laing and I discussed her book over whiskey at the capital of New York literary dissolution, the White Horse Tavern, where Dylan Thomas… actually, we met for coffee at a Pain Quotidien. (As it happened, no waiter ever came, so we conducted the interview without the aid or influence of any beverage at all.)

The Trip to Echo Spring is available wherever one most likes to purchase books!

• Amazon

David Burr Gerrard: So let’s start with an obvious question. Why’d you write the book?

Olivia Laing: The first impetus for it came a really long time ago. I was seventeen, I’d grown up in an alcoholic family, and we were studying Cat on a Hot Tin Roof at school. Pretty much as soon as I read it, I felt that this was explaining some things about a situation I’ve experienced. I guess that stayed there as an underwater interest. Over the years, I realized that Tennessee Williams was an alcoholic, and these other writers I loved were also alcoholics. It became clear that there was a book to write.

And why these writers?

It had to be writers that I loved. I think there’s a real tendency in dealing with this kind of material to be sort of trashy about it or sleazy or to take pleasure in seeing them throwing up. I really didn’t want to do that. You can get a very spiteful tone if there are people whose writing you don’t appreciate. The other thing is that I wanted some sort of commonality. They didn’t have to be friends, necessarily, but they needed to have points of encounter.

One experience of reading the book is wondering why this writer and not that writer. Why Berryman and not Robert Lowell? Why not William Faulkner? That just brings into focus just how many alcoholic writers there are.

I give that list in the beginning. You could make a similar but differently contoured book about any six writers. You could do it about six women. There are so many ways you could do it.

So why did you choose six men?

My childhood. My mum’s a lesbian, and her partner was the one who was drinking. It just felt too close to the bone. Too personal, somehow. It would make a terrific book, and it’s the question I always get asked if I give a talk or a reading. What about all of these women? Patricia Highsmith would have been fascinating. But I almost physically couldn’t do it.

It’s interesting that you mention Patricia Highsmith, because she’s not as canonical as the writers in your book. There seems to be a lot of male privilege here. These guys act horribly, and yet we either pardon them or treat their horrible behavior as part of their genius.

Absolutely. And it’s a very different story with women. Like with Jean Rhys, who I think is really interesting. To her contemporaries and in retrospect, that looks like a really sad life in a way that I don’t think we think of Hemingway’s life as a sad life. “Hey, he was a big guy, he had fun! Maybe he shot himself in the head, but…” There’s sort of a bro-ishness about it, whereas women don’t get that. It would be a really interesting thing to look at, but it wasn’t my subject. Also, my previous book [To The River] was about Virginia Woolf, so I felt like I had already done something about women writers.

That hasn’t been published in the US, has it?

No. It’s a very English book.

There is a lot in this book about sexuality. Obviously there’s John Cheever and Tennessee Williams, but Hemingway’s and Fitzgerald’s drinking seems also to have been connected to proving masculinity.

I found that really fascinating. And I don’t think you want to do something as crude as say that they were in love with each other, but there were definitely tensions and ambiguities in their relationship. And sexuality is so much a part of Cheever’s alcoholism — that he just can’t confess to himself who he is and what he desires. That sense of having to constantly bury something is really a driving force in his drinking. But then, Tennessee Williams was out and proud, incredibly courageous, and it didn’t mean that he wasn’t an alcoholic. It’s not like it saved him.

In the UK, The Trip to Echo Spring’s subtitle is Why Writers Drink. In the US, it’s On Writers and Drinking. Why the more modest subtitle here?

It was a mistake, that subtitle. It was not a good idea. It’s not answering that, really. It’s why these six writers drink. I don’t think the “Why” question is answerable. I’m a lot more comfortable with this one being more open-ended. I think it better represents what kind of book it is.

Raymond Carver is the last writer that you discuss. He has in some ways the happiest of endings, but even he was abominable to his first wife in particular.

Horrific. I didn’t actually know so much about that until I started doing the research. I kind of wanted the book to end with Carver being a great guy. “What a mensch!” And he wasn’t. There were things in his recovery that were really quite disturbing and distressing. I think he’s so wonderful that I really wanted him to heal his relationship with his children and apologize and take responsibility, and those things didn’t really happen.

I think that’s much more genuine. Most people don’t become a saint afterwards. But it was quite uncomfortable to confront. I felt it myself: “Oh, I’m disappointed by you.” But at the same time, he stopped drinking. He totally did do that. And he did create this sort of pretty wonderful second life for himself. He just didn’t extend it to every area of his life, as far as one can tell from the record.

Do you think that the fact that these men were alcoholics is part of why they’re canonized?

That is a very interesting question. I wonder, because it’s such a part of the myth of the great American twentieth-century writer. A kind of manliness, almost a parodic manliness. Hemingway with his guns. Being able to drink hard. That sort of toughness. I wonder if the lifestyle has to go with it.

More recently, we’ve seen it with David Foster Wallace.

People do like those stories, and they do romanticize them, they do make them seem very glamorous. And, yes, much more for men than for women. It’s a lot more attractive. Appears to be a lot more attractive. Which is ridiculous, really, when you think about it.

Looking at it from a devil’s advocate perspective, it does seem that a lot of really great writers were alcoholics. What would you say to somebody who said: there must be something there, some kind of connection, it must be fueling the writing or taking the edge off in some helpful way?

One of the things I came to think is that, certainly in these six, the desire to write and the need to drink came from a similar place. They came from these fractured childhoods. They had desires as very young boys to escape, to fabricate wonderful narratives that would take them away. They were often very sexually awkward, and that’s the way that they could make contact with their peers. So that seemed to be part of it. And there is definitely a thing about social anxiety and shyness. That’s something drinking is fantastic for: it makes you feel more confident. Which is great if you’re a little bit withdrawn and you want to be more worldly. And the last thing is stress. Somebody like Hemingway, who is under tremendous amounts of stress, uses it to self-medicate. It’s a wonderful strategy for a year, five years. When you’re doing it for decades, it comes at such a cost. The effect it has on the brain, the effect it has on the psyche. It obliterates everything that’s important in one’s life, so writing is almost automatically going to become secondary.

Both of your books have travel narratives. How did you come upon this particular genre?

I stumbled upon it, literally. It seems like a really good way of telling the kinds of stories that I’m interested in, because when one is walking, one is automatically digressing, and following ideas, and then returning to a path. If you want to write a book that involves biography and elements of science and elements of history, it’s a really good way of containing those things. The other thing is that lives are lived in places, and I’m fascinated by what remains in a place, by what doesn’t remain. It seems like a really good way of thinking about history in a way that conventional biography can’t always address. Those absences.

And the title comes from Cat On a Hot Tin Roof, this “trip to Echo Spring.”

Actually when you ask where the book comes from, it comes from that phrase. I just find it so fascinating. Brick says he’s going to make a short trip to Echo Spring, and he kind of means he’s going to walk to the liquor cabinet and drink some bourbon, but he also means all these other things. He’s in this claustrophobic house; he can’t confess his sexuality. The trip to Echo Spring is an exit to another place, and that place is what I wanted to know about, really.

Brick also talks about “the click,” where he feels at peace after drinking. One of Berryman’s most famous poems begins “Life, friends, is boring.” There’s that sense of escape.

Berryman did a Paris Review interview just before he died. He says I want as much pain piled on me as possible, I want to be crucified, because that’s what makes for good art. So I think there are these two divergent tendencies. One of them is: “bring it on, let me suffer so I can write about it,” and the other is a small boy saying “ow, this hurts, I want out, I can’t do it.” Totally contradictory impulses, coexisting in the same person. It’s incredibly potent.

You’ve mentioned bringing in science. There’s been a lot of recent popular writing that brings in science and tells a story about some genius, and then you have a study, and then you have a lesson. That’s not the sort of writing you’re trying to do.

Yeah, I’m not a fan of that kind of writing. My background is in science, but that sort of pat approach is very anti-art, I think.

So what drew you to science and then what drew you back to literature?

I guess it started with literature and then I got away from it. I don’t know, really. I was studying medicine, and there was a similarity between medicine and literature that was about narrative, the patient’s narrative. It was a kind of textual analysis, and at that point I’d done enough literature studies that applying that to people was very interesting. Janet Malcolm says that thing about how everything’s on the surface, and everything’s given away by small gestures and small interactions. I think that’s very good training for a writer. Forget MFAs. Medicine is a good discipline.

There are a lot of great writers who are doctors.

There are, aren’t there? It makes you a very close watcher. It makes you look for difference and for things that don’t quite fit. You’re looking at how things work, which is what you’re always doing as a writer.

It’s very interesting that alcoholism is connected to masculinity, since alcoholism makes sexual performance more difficult.

It’s a different kind of masculinity, isn’t it? It’s the performance of masculinity, a butch fantasy. I don’t think it’s about women or sex at all, I think it’s about impressing other men. This sort of display. I’m particularly thinking of Hemingway, with the guns. I don’t think that’s about pulling the chicks. I think it’s about power. And I wonder if the drinking is also about power. For a drinker like him, it’s a way of saying: “I can take more of this poison than you guys can.”

Writers tend to be introverts. Is a lot of writerly drinking just about longing for connection and killing inhibitions?

Maybe. And whatever kind of person you are, writing is a tough life. You are totally on your own. You have to be on your own to write. Lots of my friends are film directors or in theater. Their creative life is so different, in that they’re constantly collaborating and working around other people. Writing seems to me one of the most extreme art forms, in that you have to spend hours and hours each day by yourself with this world you’ve created. Until you get to the editor stage, which is a long way down the line of the book, no one really cares what you’re doing, no one really cares about this thing you’ve managed to do with a sentence or a paragraph. However damaged or introverted you are, or however totally healthy, there’s still a need to change the channel. “Now I need to go to the bar and be around people and noise.” This is a punishing life.

You’re not a teetotaler, correct?

I drink. I drink like British people drink: moderately. I know that this would not be an addiction for me. That’s where the genetic side comes in. There have been points where I’ve maybe drank a bit more than others, but it’s never felt like it was becoming habitual. Whereas I’ve had friends who have been alcoholics. Their relationship to alcohol was totally different. That’s something I wanted to contend with as well. These guys weren’t heavy drinkers: they were alcoholics. That’s a very specific thing, an entire personality structure. Whoever you were before, it takes you over. So you can watch them becoming these almost vampiric figures. I don’t want to overdramatize it, but it’s possible to see that alcoholic personality emerging in all of them. Like Berryman phoning up his students in the middle of the night and threatening to kill them. He had been such a decent, ethical teacher, he took teaching so seriously; that’s not the person he was, yet that’s the person he became.

A lot of people say that writers today are too cautious, their lives are too calm. What do you think about that?

It is said, isn’t it? A lot of what we haven’t said about drinking is that it’s the twentieth-century story. Everyone was drinking like that; it was a much more lubricated society. That’s really wound down. Even when I began working at newspapers, people drank at lunchtime. That changed very quickly. And then it was very much frowned upon. So that’s the direction our culture’s gone in. I don’t know that it’s necessarily problematic.

Do you feel that contemporary writing is safer than the writing that you’re writing about?

In terms of the process or in terms of the product?

The product.

No, I don’t. I’m never certain about the MFA culture — I kind of think that writers should have lives that are something other than writing. I think that writers should have life experience. But I don’t think that writing has become more conventional or conservative. There are such exciting things being written all the time.

But you would say: Go to med school rather than the bar.

(Laughs) Possibly. That might be my advice. Seems a bit sadistic, though.

David Burr Gerrard’s debut novel, Short Century, will be released in March. Photo of Fitzgerald’s grave by Melanie Dawn Harter.

New York City, January 8, 2014

★★★★ Brutal still, but relenting. The Hudson in the distance gleamed in irregular spots. Double layers of socks caused a squeezing pain somewhere among the metatarsals on the walk west. Up close, the river was frozen over by the shore; the ice had fractured around the old crumbling pilings, so that each one poked up of its own jagged little pyramid. The bike bath and the park were completely empty, emptier than they’d been for the hurricane. One man and a dog were out at the end of the pier. A raised rim of snowy ice traced the undulating line where the solid freeze and the plates of floating ice were slowly colliding, the irregular lozenges heaving imperceptibly and then perceptibly. Further out, the ice made a hissing sound, punctuated by scrapes, as it flowed clear of the pier. Downtown, it was possible to forget a hat in the depths of a parka pocket when emerging from the subway. Sunshine was bright on the bricks and the mortar. By the end of work, under a white half-moon, it was an ordinary cold winter night. Hands without gloves no longer burned.

Guy Still Getting A Lot Of Visibility From Buying A Beer In Australia Three Years Ago

“A customer pays for a Fosters beer at the Occidental Hotel in central Sydney June 21, 2011.”

— Can you guess the story from the photo caption? I must confess that I could not.

A Poem By Alex Dimitrov

by Mark Bibbins, Editor

Lindsay Lohan

It’s a cold rehearsal before we all drive off.

The ride out is mindless and short on goodbyes.

And in the flurry of parties she lost her passport.

A slow smoke, a think in the old car…

how they moved through their places and phrases

and onto the bedroom where mostly we kept it all in.

People won’t tell you, but if you lose enough things you do become something.

All day the water endlessly filters so it’s not the same pool.

In the morning our photos looked darker than us

and the subject we were was a gamble (I know).

The night winds came through and the gin took it well.

Voyeur. Soho House. No one told us about us.

I don’t remember, but you wanted me happy or loose like your change?

Because it’s not written here or it’s not written well

and the boys flitted out of the Aero like men do.

From one to two I saw three. No mistake. Nothing but bones and some flesh.

And then you. They said you sped through those hills and would not stop.

They said you had nothing to say in Marina del Rey.

Reno — Monroe — 1960. I forget his name, Perce’s name.

I know all these lines, John. I promise you I do. Yes, baby, we know that.

And Cook, presumably speaking to Huston, said kindly on the recorder:

“We must have 86,000 feet of sound film by now.”

So tonight, we’d like to invite only you to this soft light.

It could be your first time, it could be a waste.

Her arm was full of bracelets, one of which, she said, had been given to her by S.

And sometimes I think: I’m at this dinner forever.

It’s like home. I don’t leave without paying something.

How they wrote about you, how you showed your tattoos,

how everyone had grown tired but they were tired without you.

It was late on some coast where you walked and for now it was quiet.

The gulls couldn’t tell what we were so they stared. They kept watching.

Pretend otherwise but we just couldn’t stop.

Alex Dimitrov’s project Night Call is forthcoming. He is the author of Begging for It (Four Way Books, 2013) and American Boys (Floating Wolf Quarterly, 2012).

You will find more poems here. You may contact the editor at poems@theawl.com.

Delete These Apps From Your Phone!

Delete These Apps From Your Phone! If You Feel Better And More Productive After You’ve Done That, You Should Take It As A Sign That You Need To Kill Yourself, Because Your Existence Is So Vacuous And Superficial That The Absence Or Presence Of Apps On Your Phone Has Any Sort Of Bearing On The Way You Interact With The World And Feel About Your Life. God, What A Useless Piece Of Shit You Are, App-Having Phone User. People Are Struggling At This Very Moment With The Near-Impossible Task Of Basic Human Survival And You’ve Got A Little Bit Of An Extra Spring In Your Step Because Your Phone Is A Few Apps Lighter? Seriously, Fill Your Tub With Water, Dunk Your Head In It Twice And Lift It Out Once. You Bring Dishonor To All Of Us, But Most Of All Yourself.

“For 2014, resolve to cleanse your cell phone of unnecessary apps just as you resolve to cut out carbs from your diet. Maybe you loved these apps once, maybe you hooked up with them because someone told you to, or maybe you don’t even remember how they came into your life. Doesn’t matter! The time has come to purge them from your system. We swear you’ll feel instantly lighter.”

Remember Britpop? Hahaha, That Means You Are Old And Will Die Soon

It is nice to see some love for the Divine Comedy and the Auteurs.

Maybe Sex Is The Least Fun Thing Two People Can Do

by Desiree Browne

Kirin McCrory is 25, lives in New York, and doesn’t like sex. At least, not that much. She’s normal insomuch as any of us is normal; she happens to like boys and she likes dating, but as for sex? “I’d rather analyze a good book,” she said to me one night at a bar. Kirin is my friend, and when she said this I thought she was out of her fucking mind. Or that she had a weird hormonal imbalance or was living a PTSD-crippled life. The sky is blue, water is wet, and everyone likes sex.

Kirin isn’t traumatized, isn’t ill, and isn’t asexual. Asexuality is a real thing: people who are asexual develop romantic attachments but rarely have the sex drive to go with them. Unlike asexual people, she both develops romantic attachments

and has a sex drive. She’s not a plain old prude. What she is is a person with a nuanced view of sex that may resonate with the rest of us horndogs more than I might have thought at first.

Desiree Browne: You’ve said in casual conversation that when it comes down to it, you’d rather enjoy a good book than have sex and that talking to a man about his tastes in books and music is more interesting to you than sex. I thought that was really interesting and kinda shocking, if I’m honest.

Kirin McCrory: Yes! I’m glad you reminded me what I said, because that night is a little hazy for me and I wasn’t sure what sparked your interest.

But yes, I have a very bizarre point of view on sex and, in general, being with someone. Or, not bizarre, but uncommon. Generally when it comes up, I feel like I come off sounding like a severely repressed Anglo-Saxon Puritan, or a robot.

Yeah, my knee jerk reaction was oh my God, soooo repressed, especially for someone in theater. But then I was like, ok, I will withhold judgment because I do actually want to understand.

I too spend a lot of time thinking, “Am I just very repressed?” It isn’t that I don’t enjoy being physical with men, or that I have no desire to be sexual. For me, it comes down to this: I do not experience a lot of extreme physical pleasure. The heights are not there for me. I have definitely experienced physical orgasms, but it’s never the mind-blowing event that it is for some people. I am a very over-analytical, intellectual person, so it’s very possible that my mind is holding my body back from experiencing a deeper, more transcendent orgasm, and I suppose that is something I could explore and experiment with and devote attention to. But at the end of the day, it isn’t a realm that I find very interesting, so I generally choose not to exert a lot of energy over figuring it out.

I would rather analyze a good book than analyze what I could do for myself to enjoy a sexual experience on my own end more.

I am very big on banter and flirting and that sort of sexually charged competition between two people attracted to each other, and I am very into the tensions that build in all sorts of sexual situations, physical or otherwise.

But the release, as it were, isn’t great?

Yeah, exactly. But the most important thing about me, I think, is that that does not bother me. Which makes me sound, once again, like an ignorantly repressed woman, I think, by modern standards. “Oh, I just don’t care that I’m not orgasming! It’s really okay!” when we all know it isn’t. But I do truly feel that it does not bother me. I enjoy sex as an act that brings me closer to someone I would like to be intimate with. I think it’s a lot of fun if things are jiving with the right person.

But I find there’s a lot of pressure — which is probably warranted! — for it to get both people off and be a really beautiful moment of individual-and-thus-collective release. And that doesn’t happen for me that way.

Can you give me a brief overview of your “history”? Like, when did you start dating, when did you realize you were “different,” how did you come to terms with your position on sex

Sure. I did not date until late college. I had my first kiss at 18, in college. I fooled around with someone for the first time at 19. I lost my virginity at 20 at the very end of a sort of bizarre summer fling. I’ve slept with 5 people but only 2 of those were regularly recurring partners. I would say I’ve always known that I was not as interested in sex as other people I knew, because my solo sexual relationship is pretty limited. ‘Bout to get TMI, but we’re talking about sex anyway, so whatever — I’d say I masturbate, on average, about once a week, and have for most of my life. So, I mean, I think I always knew that I would just rather be doing any number of other things than focusing on sex at all.

Obviously, once I became sexually active I had to start dealing with how I felt about having sex with someone and not thinking about having sex with someone. And there have been about two times in my life that I’ve had amazing, stand-out physical moments with men. But neither of those was during sexual intercourse, and neither of them were, like, white-light, head-thrashing, body-shaking moments either.

What were they like?

Both times were during oral, and I would say it was like being dunked in an amazing, warm bath and soaking there.

That’s not bad, though, the warm bath thing. It’s definitely sounds comfortable and like a release, like a good payoff for the experience.

Exactly! And both of those moments were great. And I would never decline experiencing them again. But ask me if I’d rather have that moment or finish a great book, and we both know what my answer’s going to be.

Not focusing on an orgasm in and of itself isn’t wrong or uncommon. I’ve read that it’s a very Western thing to focus on the orgasm rather than the arousal and the experience that may eventually get you there.

Yes! I can see that, definitely. Eastern sexuality is a lot about the whole journey of wooing and seducing and finding the moments of intense pleasure in every step along the way.

Which, actually, I would probably be way more into.

I think what you described earlier — the banter and tension built when two people have their clothes on — falls into the category of romance, which is kind of separate from sex, no?

I guess it depends on your separation of the two. Again, being someone who is so deeply intellectual, I put a lot of weight in general on my ability to interact with someone else’s brain. So whereas banter for others might be a romantic intimacy-building experience, honestly, for me, banter becomes way more of an important mind fuck, in the most literal sense. If we can have an amazing conversation about a novel, or if I can find someone whose sense of humor is as sharp and as combative as mine can be, I might as well be naked and getting freaky. That is important to me.

So that night in the bar you said you were sort of asexual but this actually kinda sounds more like being a sapiosexual. Which I sort of wrote off as the kind of bullshit people who are “deep” say but what you’re saying sounds a lot more genuine.

Right, because it’s a compromise, or a concession, or a building. If I meet a man who can do those things for me intellectually, I want to rip my clothes off and do whatever he wants me to do to satisfy him, and I’ll enjoy that. It’s a give and take.The same way sex is for people. It just spans a couple different arenas for me.

I feel like when people say sapiosexual, it comes off as meaning they aren’t interested in sex at all, a sort of condescending view of the physical.

Right. They’re like, “Oh, I’m attracted to people’s minds.” But you can just as easily like boobs, and that’s okay, too.

Right! And I don’t feel that way. I get why people like sex, just for sex, and I get why that’s super important to some people. And, for someone who doesn’t really like touching people in casual circumstances or in public or anything like that, I do really enjoy physical intimacy with a man I’m into. There’s no avoidance of the physical on my part, which is different than some people who claim sapiosexuality or a disinterest in sex. I freaking love making out with people — it’s just that it’s got to be someone who’s just one-upped me in a wits’ battle first. I will roll around with you all day long if you’ve done that successfully.

So Joan Sewell wrote a book a few years ago about how she has a low libido and after trying everything she could do to “fix” it, because the culture made it seem like something was wrong with her she just came to terms with it. She goes so far as to say a lot of women are faking how much they crave sex in order to be equal to men and that many would rather read something great. She’s gotten to a point where she negotiates and manages sexual experiences with her husband and it doesn’t actually include a lot of intercourse. What do you think?

I don’t want to say I think anyone’s faking it, but I do think that — and it’s a totally natural and necessary order of things, to reverse previous societal beliefs so strongly — we’ve become obsessed with our enjoyment of sex as a society. We’re all supposed to be okay with sex now, which somehow translates into wanting and enjoying and even needing sex, men, women, doesn’t matter. That’s where we’re coming from. We came from sex as a procreative tool for women and enjoyment for men, and we needed to balance that out by asserting that everyone can and should enjoy sex.

I think we’re coming to find, with many things, not just with sex, that people are just more complicated and diverse than that. And that’s becoming the thing we need to try to accept now.

I would also say that my case is different from Sewell’s. Libido just means sexual desire, and again, I do have that. I’ve yet to have to — or want to — schedule sex for my partner’s sake.

I think that when it comes to sex people mostly just want to know two things: am I doing it right and am I really not alone in my strange desires?

Right! But it’s like that with everything, I think. I think that about cooking, you know.

Am I doing this right? Am I weird for wanting to eat chili powder in some sort of chocolate concoction? But sex has been, in my view, unfairly pressurized. Humans sit around all day, consciously or unconsciously, wondering if they’re doing everything right, or if what they like in any realm is weird comparatively.Clothes, books, music, food, lifestyle, everything.

Wow, the subject of getting laid just got really existential.

That’s how I feel about it, though! We’re eating food way more often than we’re having sex. Why are we not discussing my bizarre neutrality towards, I don’t know, grains right now? (Not that I have one; I love grains.) But that’s what it comes down to for me.

You talked about give and take. So in these situations, you’ve enjoyed really good conversation and that’s you taking. So then you give sex? In that case, sex isn’t really about you. Or am I wrong?

No, you’re mostly right. It is about me, in the sense that I do get enjoyment out of it, and it does bring me closer to someone — so I’m always getting something from sex — but it is more about knowing someone else enjoys it more straightforwardly than I do.

I almost pity the men who’ve slept with me. I’ve tried to explain it to most of them, and I imagine, in today’s modern world, they have serious complexes about whether what they’re doing is backwards or selfish or misogynistic. They’re probably freaking out in their heads every time, thinking, “She doesn’t like this, but I respect her and I respect women and oh my god what does it mean for a man to be essentially taking sex from a woman, that’s fucked up.” Not that I don’t have my own complexes about it, but I can feel for them.

Do you feel like your position on sex makes you a bad feminist?

No, I don’t. I feel that feminism is all about equality and choice, and not a definite position on anything. Of course, sometimes I worry if it means I’m a bad feminist because we now put so much pressure on sex as some sort of symbol of liberation, but at this point in my life, I’ve come to terms with the way I feel about it. It’s a thought out and experienced opinion on my part, and that’s what feminism is about. I get to feel the way I feel about it, and you get to feel the way you feel about it.

Also, I mean, for someone to say that she cares more about what a man thinks about a book than whether she orgasms or not is not exactly a reversion to any out-dated position for a woman. Women weren’t running around in the 1950s saying they needed a man who made their brain explode before he got in their pants.

But one feminist view might be like, well, if you don’t like sex it’s because the patriarchy has crushed your naturally libidinous soul and now we must rehabilitate you!

Right! Exactly. That’s the worst version of feminism, and, in my opinion, isn’t really feminism. At this point we should know that humans, men and women, are more complex than that.

I had one truly awful experience with a guy I was seeing. We were fooling around one night and intermittently discussing my weird views on sex, and he pinned me against a wall (something I’m a fan of, under normal circumstances) and said, “I think you just need to be liberated.” And I just felt my blood go cold and my stomach drop. I’m sure he thought he was being helpful, but it felt so disgusting and offensive at a moment when I was very vulnerable with someone. I left shortly thereafter and sobbed the whole walk home.

That’s awful. And not helpful. You didn’t ask him to fix you. I want to backtrack and ask you why you masturbate once a week if it’s a warm bath feeling at the end (assuming you orgasm on a regular basis).

Again, I feel like me saying that I don’t care about orgasming means to most people that I don’t feel ANYTHING when it comes to sex. I masturbate because I do have sexual urges and I do still get pleasure from engaging in sexual intimacy, whether it’s with myself or others. But when orgasming is difficult or unimportant, there just isn’t a lot of point in sitting around touching yourself. Not that there’s no point, but there’s less impetus to do so.

How do you negotiate your feelings with being in theater. I know you can’t make generalizations but it’s been my experience with my theater friends that they have pretty liberal attitudes toward sex and act accordingly.

But my attitude is liberal! It is! If we want to be textbook about it, I might even say my view is more liberal than some others! I have no stipulations. If I want to have sex with you, I will have sex with you. My low personal stake in sex means that I am way more open to whatever the other person may be into, and I have no judgments when it comes to that. And I don’t judge anyone for wanting to have lots of sex with as many different people as they like, if that’s what they really enjoy.

Desiree Browne is a writer and editor in Brooklyn. Her mother once told her she was oversexed; a high school crush was sad she was still a virgin at 15. Follow her on Twitter @itsdlovely. This conversation has been edited. Australian street shot by “Petra.”