Tambien, "Collagelinger"

How hot is it going to be today?

I never thought I’d get to a point where I hoped it was so hot that the weather became the only topic of conversation, that discussions of the heat crowded out every alternate topic, that we spoke of conditions outside to the exclusion of all other things. And yet here we are. It’s going to be hot today (and, if you read New York magazine, for the rest of our brief lives). Please go on about it at length, particularly on social media. Meanwhile, here’s music. Enjoy. [Via]

New York City, July 11, 2017

★★ The morning air was not hot yet but already thick. Shirt backs and bare shoulders were smashed flat against the glass of the doors of the train moving through the station. Gray suddenly appeared and some rain fell on Columbus Circle, a sprinkle that did nothing but thicken up the air some more. Fragmentary showers would happen again and maybe again. Sometimes it was just blowing air-conditioner drip. One heavy spattering burst of water came down beside a scaffold and nobody could figure out why. At rush hour the pavement was wet or greasy-looking again, on the way to the closed-off subway station. The third attempted station, on the second attempted line, was open and operating, and the platform was hot enough to raise a sweat before the train finally arrived. Up on the surface again a man went by with flecks of sweat darkening his shirt and flecks of ice cream sticking to his beard. The day at least went away prettily, with red-orange light bouncing its way to the corner of the apartment building across the way, and purple blooming in the west.

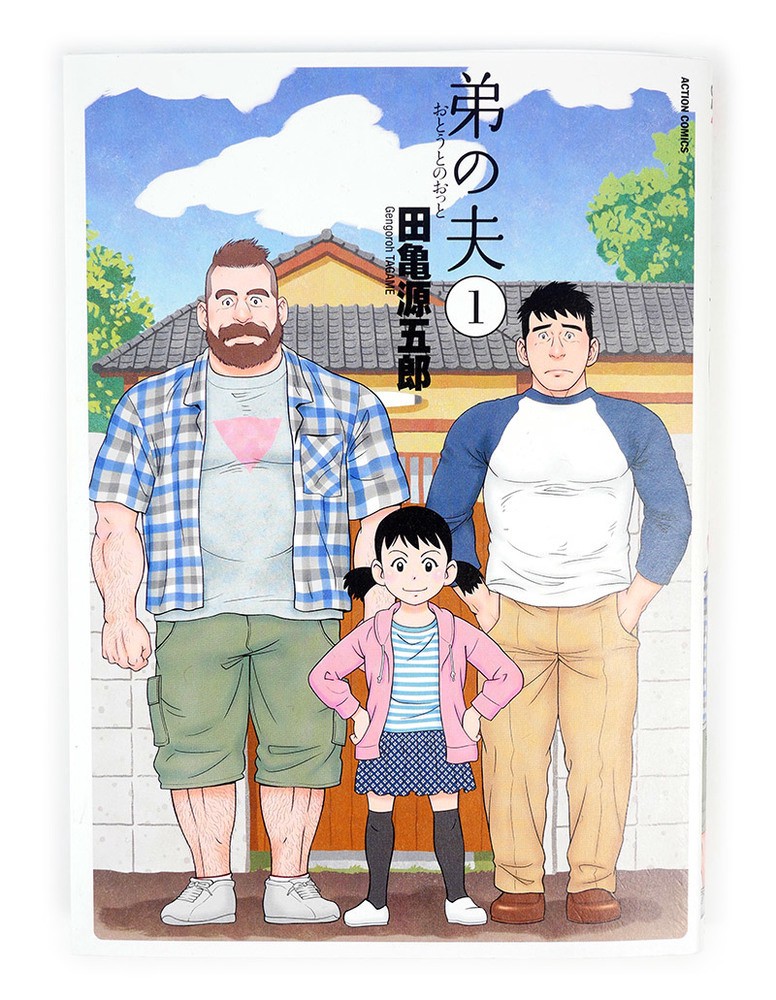

The Radical Grace of Gengoroh Tagame

‘My Brother’s Husband’ and the tradition of gay manga.

In the first volume of My Brother’s Husband, the Japanese manga created by Gengoroh Tagame, a single father hosts the spouse of his dead twin brother. After his sibling’s death in Canada, Yaichi and his daughter come to terms with it, while his brother-in-law, Mike, navigates Tokyo’s suburbs for the very first time. They settle into a wavering domesticity. That the story isn’t entirely tragic is a testament to the author’s mastery: widely described as “Japan’s most influential gay manga artist,” Tagame is playful throughout. He is assertive, occasionally goofy, and forgiving with his characters, and as Yaichi picks apart the walls of his ignorance, the narrative allows him the room to grow.

As Alison Bechdel has noted, the work is “very different from [Tagame’s] customary fare”; the artist’s oeuvre is generally queer, but it’s also a good deal more explicit. His narratives usually delve into BDSM, and S&M, lingering on the extremes of human sexuality. Since the ’80s, Tagame has pushed the boundaries of what was “allowed” in gay manga. But My Brother’s Husband is largely sexless. It’s very nearly chaste, and (almost) entirely safe for kids. And, as a whole, the work might be even more revolutionary than anything he’s produced before.

Tagame works in a sub-genre of manga called bara, which is itself a cousin of yaoi, which can be loosely defined as “boys’ love” (it’s an acronym derived from yama nashi, ochi nashi, imi nashi; or, “no climax, no point, no meaning”). Jamie James, in an essay for The New Yorker, notes that the genre “was coined in the nineteen-eighties to identify sentimental stories about beautiful boys”:

In its essentials, yaoi is an updating of the cult of boy worship in feudal samurai culture, known as shudō, the Way of the Boy, in which an adult warrior took an adolescent disciple as his lover. In the Tokugawa shogunate (1603–1867), this pederastic arrangement was not only tolerated but normative, regarded as a more refined taste than the love of women, with spiritual connotations. The seme–uke dichotomy in yaoi fiction follows the samurai model, with the key modern innovation that the lovers are the same age, or nearly.

But while yaoi is generally marketed with a female audience in mind, and plots whose formulas skew towards more heteronormative norms, bara is almost always created by and for gay men. While yaoi’s character’s often don’t identify as homosexual, the opposite is true of bara. Yaoi’s characters are slim in proportion, while bara’s are muscular, if not bearish, damn near all of the time. And if yaoi doesn’t always belie sex, bara’s intercourse is multi-paneled, explicit, and occasionally fetishitic; but, in a funny way, it makes sense that the genre’s most revered practitioner has conjured a loving portrait of a man just beginning to reckon with the layers of sexuality.

Distributed and translated by Pantheon Books, My Brother’s Husband is one of Tagame’s first legally distributed English publications. But American readers aren’t entirely unfamiliar with his work. In 2013, PictureBox published The Passion of Gengoroh Tagame, a sold-out compendium. Gmunder Books has regularly published him in English since 2014. My Brother’s Husband netted Tagame a Japan Media Arts Award from the Agency of Cultural Affairs (a big fucking deal), and, with the series, a creator whose work couldn’t have otherwise have surfaced in polite conversation has garnered praise and widespread adulation.

In interviews, Tagame is very self-aware. In a chat with the Huffington Post, he noted the structural differences, saying he was “much more careful and deliberate about the art then, so it wasn’t as much about the story. It was about the graphics. It wasn’t pornography, and it didn’t depict sex; it depicted eroticism.” But Tagame hasn’t sweated the implications of the change in his aesthetic too much either, and talking with Chris Randle over at Hazlitt, he notes that, “in stories and in eroticism, I’m very particular about heroes, and I’m very concerned with the idea of the hero, but the hero that I fantasize or dream of isn’t someone who builds nations or brings peoples together, but a person who’s falling apart.”

Throughout My Brother’s Husband, those same sentiments are embodied by Yaichi: he is constantly coming to terms with himself. First, he navigates his brother’s homosexuality. And then his revulsion towards it. And then his daughter’s unvarnished acceptance, and the apprehensiveness of his neighbors, and watching him reckon with his brother’s ghost is as affecting as any conflict in literature. At one point, after Mike explains that there was no “female” in his marriage (“We were husband and husband”), it takes Yaichi watching the epiphany spread across his daughter’s face to jumpstart his own illumination. “I had no idea,” Yaichi says, staring into nothing, “About any of it.”

The work’s acclaim in Japan is a minor miracle: despite recognizing same-sex partnerships in a handful of Tokyo’s wards, the nation as a whole is largely apprehensive towards same-sex marriage. There are Pride parades in the larger cities, and a scattering of gay bars in those same hubs, and the threat of physical violence may not be as high as in some countries, but social stigma, from the outset, is a big enough deterrent to keep folks from living openly.

But Japan rewriting the rules for gay fiction shouldn’t be entirely shocking, either: the country’s culture has made space for male-on-male sexuality in print since the seventeenth century. From Ihara Saikaku’s story collection The Great Mirror of Male Love (1687), to Utamaro Kitagwa’s erotic wood prints, to Ogai Mori’s novel Vita Sexualis (1909), Japanese artists have investigated the contours of gay love, free of the West’s religious stigma, for centuries. What isn’t entirely accepted in public has been given free roam to expand on paper, and it could be as Yukio Mishima alludes to in his novel Confessions of a Mask: “Prudery is a form of selfishness, a means of self-protection made necessary by the strength of one’s own desires. But my true desires were so secret that they did not allow even this form of self-indulgence.”

Since the ’90s, the American entities publishing gay manga in translation have continued to expand, chipping their way around the mainstream. But their prevalence in the States’ comic culture isn’t nearly as expansive as the medium’s counterparts: ever since the introduction of series’ like Lone Wolf and Cub, Appleseed, and Sailor Moon around the late 80’s, American comic publishers began investing in manga as a business booster. Animated franchises like Dragon Ball, Akira, and Neon Genesis Evangelion multiplied this expansion in the 90’s, before Pokemon solidified it; and Japanese publishers set their own sights on the stateside market shortly afterwards. But of the manga and anime series’ that have made it big in the States, none are overtly gay. And while, a fraction of a fraction the time, a series suggesting homosexuality slips through the mainstream, until the early-aughts your best bet for finding bara and yaoi were the illegally scanned translation hubs pocketed across the internet.

But while the scanlation hubs persist, a handful of American entities are legally publishing gay manga. And some like MASSIVE GOODS, have worked every available angle (to great success), from manga to apparel to accessories, gaining notice from Out to MTV to the New York Times. Founded by Anne Ishii and Graham Kolbeins, and currently helmed entirely by Ishii, MASSIVE has gained a substantial following since its inception in 2013. But as Ishii, corresponding over email, put it to me, with “what felt like a clearly profit-less book model, it felt obvious to start a fashion line”:

If I were to say one thing about the MASSIVE aesthetic, it is maximalist. Speaking only for myself, minimalist trends depress me. I mean I love clean lines and gajillion dollar Eames chairs like everyone else but I also cringe around Helevitca. I want to feel like I’m being hugged by design, not being delivered an SAT exam. Graham and I have both been fond of the bold and the large and the beautiful. Chip Kidd, who contributes to our aesthetic, and designs all the books, is also a sort of a maximalist, in my opinion. I’ve tried to make what I think are relatively “safe” designs, but perhaps because the intent is visibly disingenuous or because our fans have so firmly made their imprint, the “safe” things don’t move with the alacrity of our massive looks

Ishii noted that “gay manga to many people is content that supersedes whether and how it is sanctioned.” And, in this way, the publication of My Brother’s Husband, from a major publisher is a quiet, sonic achievement: an art form whose primary audience could’ve only been grown on the outskirts of the internet has entered the American book sphere.

Tagame is clear to distinguish between pornography and eroticism; and despite its lack of obvious sexual tension, the men in My Brother’s Husband are definitively beautiful. The lines are full and bold. Their bodies are stout. The expressions on their faces are emotive in one panel, and aggressive in the next, before that anger dissolves entirely on the following page. Of course Tagame’s a veteran of his form, and a master in the craft, but the emotion in his work doesn’t always connote to sex. Sometimes, the subjects are a means to beautiful art. And, as he notes in an interview with The Huffington Post, that Tagame has molded his abilities to realize these very particular narratives is shocking, and heartening, and wholly inspiring:

“At home, we had anthologies of classical art, and I was highly attracted to and influenced by the Hellenistic period. The most modern I went to was probably Baroque and pre-modern. In what I’m depicting as sexual humiliation, Western religion is a big influence: Caravaggio’s depictions of Christ’s humiliation or his crucifixion, obviously. Things like that are in line with what I want to depict. Conversely, in the Japanese artistic tradition, there isn’t really praising the nude. There are certainly depictions of violence, but there isn’t a tradition of just the full male nude body. So in that sense, Western religious art has been a huge influence.”

It mirrors a sentiment that Samuel Delany, a noted fan of bara, expressed in last month’s interview with The Boston Review

Not all explicit sex is pornographic. It can be educational, and I expect that a room full of forty to eighty year olds having sex and discussing their lives would be just that: educational… They aren’t breaking any laws. They’re enjoying themselves and caring for their own community. And they’re talking honestly and intelligently.

Sometimes, that beauty incarnate is the goal. Depicting it in a very particular way, for a very particular audience, absence of erotics can prove erotic enough. One bara artist, Inu Yoshi (himself drawn to gay manga through Tagame’s work in G-Men magazine) has said, “I don’t really want to put erotic scenes in my stories, but it’s what sells magazines, and the magazines say it has to have that.” Another creator, Fumi Miyabi, describes his own work as directly influenced by that aesthetic, noting that, “I saw Tagame and Go Fujimoto and Keiichi Takasaki. I saw what I imagined gay erotic comics were supposed to look like, but it wasn’t just gay — it was also really great manga.”

Some artists are attracted to the aesthetic. Others are drawn to those came before them. And for others, as Tagame has elaborated for Vice, the distinction between those two impulses is infinitesimally small:

Porn is a search for the perfect erotic expression. It’s not necessarily self-assertiveness, nor a status symbol, but uncontrollable desires. Pursuing such pure pleasure is less complicated. In such pursuits, pornographic art is pure, fine art. My goal is beyond manga or porn, but to aim for the level of Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio.

There’s a moment in Édouard Louis’s novel, The End of Eddy, where his narrator turns to the moment he acknowledged the “pain” of his sexuality:

I thought that in the end I would get used to the pain. There is a way in which people do grow accustomed to pain, the way workers get used to back pain. Sometimes, yes, the pain regains the upper hand. They don’t get all that used to it, really, they work around it, they learn to hide it.

Tagame’s work covers a sort of pain in its own right: the pain of loss. The pain of difference. The pain of becoming something else, something new. Throughout My Brother’s Husband, Tagame’s characters are constantly coming into themselves, but the most affecting moment could be a scene, late in the volume, when a neighbor’s kid skips school to approach Mike in Yaichi’s home: “I came over here,” he says, “A few times to see if you were real.”

“All I think about are boys… and I realized that’s always been the case. I’d heard things: homo, gay… I knew about it, but… I didn’t know who anyone was. Nobody I knew anyways. When I looked online, I realized there were a lot of people like me. And I felt better. But some people wrote nasty things. I got little scared, and I realized I should probably hide this.”

“So I deleted my history,” says the kid. “I pretended not to care.”

Any motion to tell gay stories is a lantern in a dark, crowded room. All of it always matters. And, on paper, an artist working within such a niche genre, in a form supporting reams upon reams of content, shouldn’t exactly be earth-shattering. But in forcing his characters to come to terms with themselves, Tagame challenges his readers to do the same.

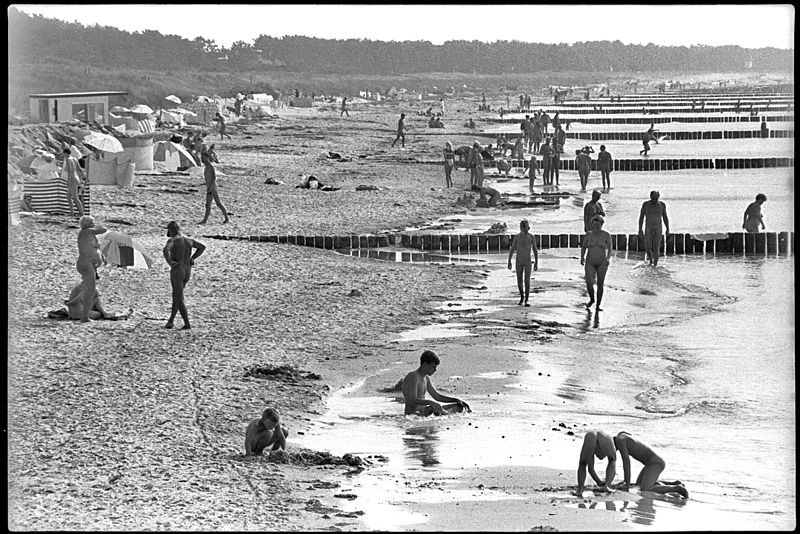

The Best German Beach Reads (For Nude Beaches)

Deutschland über us.

Every time I visit a German-speaking country, I am invariably asked how many German relatives I have. When I explain that alas, my last name is an Ellis Island fabrication and I hail from Russian Jews, my interlocutor wonders why I speak their language on purpose. Then, without fail, some form of this conversation happens:

ME: I have a lifelong love of German literature.

GERMAN (confused): Why?

ME: German literature is good.

GERMAN: What, like Goethe?

ME: Also Kafka.

GERMAN (annoyed): HE wasn’t German.

I get it. A non-German proclaiming to “love German literature” because of the Austrian-born Czechoslovak Jew who also happens to be the most popular German-language author of all time is, to Germans, like a tourist in America who professes to “love American food” but means pizza. It’s somehow both the biggest cliché possible and culturally impure.

The Germans are right, of course (their preferred state of affairs). There is infinitely more to their literary tradition than Kafka — who himself was so indebted to Heinrich von Kleist, an actual German, and Robert Walser, a Swiss, that it’s impossible to understand him without them, FWIW. (Michael Kohlhaas and Jakob von Gunten. You’re welcome.)

To my credit, once I entered graduate school and realized that one can’t pass one’s PhD comprehensive “breadth” exams by having read the same passage of The Trial wearing four different outfits, I did, once upon a time, have an excellent command of everything from the Niebelungenlied to Paul Celan’s “Todesfuge” and beyond, a.k.a. The German Canon. (This did not, however, stop me from mistaking Schiller’s skull for Goethe’s in the first edition of my own damn book — but, as Kafka once wrote, the shame of that will outlive me, so let’s not dwell on it.)

Yes, for a small country, the Germans have created an impressively disproportionate amount of literary greats. And Germans are also an unapologetically bookish people: according to this 2015 survey by Allensbach Media Market Analysis, damn near half of them read a book a week — as opposed to the (at least) 20 percent of American entering college freshmen who have not read a full book in their entire lives. (Good news, Republicans — can’t fill their heads with Commie nonsense if they don’t read!!!!)

However. You’ll be relieved to know that when it comes to what actual Germans are actually purchasing and reading right this second—the actual content of their actual vacation totes, tomes to be perused as they strip down to their leathery butts and bake au naturel on the nearest FKK-Strand, which is German for “regular beach” — is not Schiller’s Über die ästhetische Erziehung des Menschen, but rather the banal mixture of highbrow and low that we dumbasses over here also like to read when we’re not busy emailing Russians.

The German equivalent of the New York Times Bestseller List is the Spiegel Bestseller List. Let’s take a look, shall we?

Die Geschichte der Bienen (The History of Bees), Maja Lunde. This translated Norwegian novel set in 19th-century England is the Nummer Eins Spiegel Bestseller this week in the category “Belletristik” (BELL-uh-TRISS-tik), which is the Teutonic version of the hoity-toity French word for “fiction.” (It’s always awesome when the Germanic goes Latinate.) Its protagonist, William, is a Samenhändler (SAH-mun-HEND-lur), an excellent word that technically means “seedsman,” a profession that I am pretty sure is endemic to 19th-century England, but that also, thanks to the double meaning of Samen, also literally means “semen merchant.” (Also a book I’d read.) It looks good, but, in the immortal words of every German ever, “NOT A GERMAN AUTHOR.”

In fact, there is not a German-originated book to be found on the Spiegel fiction bestseller list until number 13, Sebastian Fitzek’s Das Packet (The Packet), a “Psychothriller” which enters the list well below various and sundry German translations of American YA fantasy, Italian mystery, and a Danish thriller called SELFIES.

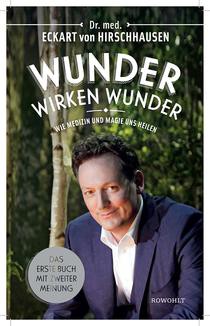

Over in Sachbücher (SOCK-buuuuusher, or “thing books,” aka nonfiction), underneath the number-one German translation of Age of Anger comes possibly the Germanest book ever to German. Wunder wirken Wunder (VOON-dur wirr-kun VOON-dur) has various workable English translations, from the ultra-literal Miracles Work Miracles to the equally tautological Wonder Works Wonders, thanks to the multiple meanings of the word Wunder and the fact that, like many German words ending in -er, the singular and the plural are the same. But the truth lies somewhere in the middle; I’d probably translate it as Wonder Works Miracles. Or maybe Miracles Work Wonders. Anyway, it’s by German medical doctor and definite not-crackpot Eckart von Hirschhausen (ECK-hart fone HEERSH-house-un), the Germanest name ever to exist, about a topic that I would choose if I wanted to write WHAT IT MEANS TO BE GERMAN: THE BOOK.

Ahem: “Science has taken the magic out of medicine, but not out of us as people…What is healing magic, and how do you differentiate it from dangerous hooey?” When you get hurt or sick, a German’s first recourse is to tell you to take a brisk walk in the woods, so it only makes sense that their number-two bestselling “thing book” this week is about magicking yourself well. (Number three, by the way, is Heilen mit der Kraft der Natur, or “Healing with the Power of Nature.” QED.)

However, my personal pick for this year’s Sommerschmöker (ZOME-ur-SCHMOOOK-ur, the amazing German word for “beach book” that literally means “summer schlock”) is the Spiegel’s number-nine Sachbuch, Keine Zeit für Arschlöcher! (KINE-uh TSITE fooooer ORSH-loooch-ur), or No Time for Assholes!, a memoir by Horst Lichter, the “most beloved TV chef in Germany.” “This book belongs in your beach bag!” commands German Amazon, and I must agree based on mustache alone.

For Germans who like to read boring, humorless important things on the beach, the Spiegel list also boasts biographies of both Angela Merkel and Emmanuel Macron. Notably, however, there is nary a single book containing the T word anywhere in the Spiegel top 20. Not as “author,” not as explicit subject — blessedly, blessedly nowhere.

Yes, while Germans seemingly can’t get enough of the Sexmonster-in-Chief on their news pages, when it comes to the reading they may or may not use to shield their special parts from the sun as they enjoy the latest Summer Schlock, this week, at least, they seem to have no time for assholes. (Because they’re too busy healing with magic.)

But It's Comedy, So Laugh

The agony and the apathy of Jerrod Carmichael in ‘8’

Jerrod Carmichael starts the trickery in his new HBO special with the title, 8. I’ve spun into obsession trying to decode the meaning of this single symbol. 8 is Carmichael’s second stand-up special. As far as I know, he doesn’t have a vault somewhere with six more hiding, which rules out reading the title as a Zeppelinesque chronological milepost. It’s also not a pull from his material, in the mode of so many stand-up specials. None of his set-ups, punchlines, premises, tags or ad libs even casually reference the number. So what is “8?” Why is 8? I’m embarrassed to admit how much I care.

“Eight is a really personal and recurring number in my life” is the only public explanation I’ve found, and I’m sorry, but that’s just not enough for the reader-response critic in me.

Maybe the title is a play on the ridiculousness of naming specials at all, the way the Replacements called their fourth album Tim as if it were just some guy. I like this theory, but I don’t love it. For one thing, the number doesn’t make that joke as well as a person’s name. For another, that would mean the title is technically the first joke of the special, which would be clever, but that sort of jokes-to-the-gills maximalism isn’t Carmichael’s style. Instead, the title seems less a joke than an inscrutable fact marking the special as a monolith to behold and ponder.

All of this is to say I’m close-reading a stand-up comedy special like it’s Ulysses. As a comedian, I get what a bad look this is. It stinks of jealousy. It’s also stand-up comic code not to talk comedy-as-art for long, if at all, without cracking a joke. It screams pretension. But I can’t help the truth: watching 8 gets me jealous and pretentious. I’m leaning into it.

Throughout 8, Carmichael takes the opposite approach. He pulls away to tell the audience the myriad things about which he doesn’t care: the environment, the lives of tigers, all the work it takes to maintain a relationship. His biggest care over the course of the hour seems to be impressing upon us just how little he cares. Here is a sample of the ways he emphasizes his apathy:

- I want to care about things. I really do.

- I want to feel.

- I wish I felt things.

- I’m trying to care and feel things and feel strongly about things.

- I tried to care. I really did. It means a lot to me that you know that I tried.

These are transitions — his equivalents to “So what else is in the news?” — not his jokes. There are plenty of other pieces about 8 that can vouch for the quality of Carmichael’s punchlines, thanks to the press’s willingness to engage in the point-missing exercise of printing a comedian’s jokes without context in black and white. But my favorite review of the special comes from an IMDB post, written by French user Ersbel Oraph, with the subject line “Did not laugh once:”

I did not laugh once. The whole hour. Yet he is good. I would go as far as compare him to George Carlin. If he is that good before 30, maybe he will go far beyond what Carlin did two decades later. I don’t know. I will have to see it. But now, he is good. The tempo is slower, but his public is less used to his kind of thoughts. And Jerrod is good. […] I did not laugh once. I was shocked people laughed in the audience. But it’s comedy, so laugh.

While I laughed more than once watching 8, Ersbel and I fundamentally agree. And Jerrod is good. His craft is pristine and chock full of tricks. He extracts laughs from repeating a sentence but emphasizing different words (He turns “I had a dog” into “I had a dog,” and the line goes from set-up to punchline in the process). He masters misdirection by posing big questions and surprising with small answers (“What do I believe in?” leads into a bit about the exhilaration of avoiding a pregnancy scare). He pauses in the discomfort of his provocative premises before puncturing them with punchlines, and he generates extra laughs from doing so (Calling a boyfriend’s job thankless prompts awkward giggles even before he unspools an ideal example of an unsolicited supportive text message to prove the point). He interacts with audience members without relinquishing control, by asking them questions and responding to their answers with comebacks that reveal those answers as inessential (His opinions about animals and the environment are built to withstand the objections he solicits). He’s alley-ooping to himself off the backboard of his unwitting audience.

Carmichael is not a one-liner guy, neither is he a storyteller nor exactly a confessional comic. Rather, he belongs in the Bruce-Carlin-Chris-Rock lineage of truth tellers confronting us with our hypocrisies and shading in the gray areas between the cracks in our black-and-white culture. He also does this on his NBC show, “The Carmichael Show,” a throwback to Norman Lear capstones like “The Jeffersons” and “All in the Family” that used their TV families to explore difficult social issues. In episodes like “Gender” and “Guns,” the TV Carmichaels speak their minds, whether in conflict or agreement with each other’s plainspoken opinions. It’s a welcome surprise to see a show so blunt on thorny topics, knowing it’s on network TV. It’s hard to imagine Leo Burnett clients begging for airtime during the breaks in a story about Jerrod being a Big Brother to a trans high school basketball player.

It’s an even bigger surprise that Carmichael’s approach to similar subjects onstage is less strident than on TV, not more. He still discusses uncomfortable ideas, but instead of attacking them directly, he waffles, mumbles, false-starts, then changes course mid-sentence. Even more than his forebears in stand-up, Carmichael comes across like a comedy Montaigne. Sarah Bakewell wrote in her biography, How to Live: Or a Life of Montaigne in One Question and Twenty Attempts at an Answer, “Every few phrases, a new way of looking at things occurs to him, so he changes direction. Even when his thoughts are most irrational and dream-like, his writing follows them,” which applies equally to Carmichael in 8.

His waffling can be a trick too. Carmichael presents himself as a bumbler to the live audience, but he knows the force of his punchlines, even if he hasn’t predetermined his path to them. This is clear in the film when close-ups show Carmichael’s eyes alert and scanning the crowd like prey, betraying a similarity to the tigers he claims not to give a shit about. He has crafted an act that is the spoken version of a James Harden crossover.

Carmichael’s stutter step is on full display in those apathy-touting transitions that predominate the first two thirds of the special. I fell for the deke when I thought his seemingly endless claims not to care only highlighted his youth. It’s easy to be carefree when you’re young. There’s a Steve Martin quote that goes something like, “When you’re young, you make all sorts of dark jokes and think nothing of it. Then when you get older, your friends start dying, and you think twice. I’m definitely Steve Martin, and I’m pretty sure I or someone like me said this or something close to it.” I saw Carmichael’s apathy as a comedy phase he’d outgrow.

What I failed to see at first was the way his transitions change toward the end of the set. Here’s another sample of between-bit utterances from late in 8:

- What am I rebelling against?

- What do I actually believe in?

- Am I gonna find love?

- I don’t know what I’m doing. Goddammit. That’s a fear.

The truth about his apathy is right there: it’s another trick, a defensive pose in response to the fact that Jerrod Carmichael is afraid. Some of his fears are commonplace comedy fodder like premature baldness, but he also threads deeper existential fears throughout the special. What is a grandmother’s identity without baking? What would we have to face within ourselves if we didn’t have sports to distract us from our feelings? What is the point of caring about anything when the world feels so hostile? He wants to know why we’re alive and, again like Montaigne, how best to live.

By infusing his special with these questions, Carmichael has created a rare thing: a stand-up special with real angst that’s also deeply funny. His waffling works because it rings true. Some of his false starts mask punchlines, but others are the starts of questions he’s asking in earnest. Through following his intuition, he flouts the convention of the stand-up special as a mere collection of a comedian’s best new jokes or even as a more intricately woven, cohesive piece. There are no callbacks in 8. It’s a singular document of the twists and turns of one flawed man’s mind.

This singular quality would be far less potent without fellow comedian Bo Burnham’s exquisite direction. Burnham establishes a surreal tone that matches Carmichael at every turn, from showing him staring at his phone amidst the grandiosity of the otherwise dark Masonic Hall green room in the opening sequence to the first and last shots of the set itself, which give the impression that the entire evening might be a figment of Carmichael’s imagination. Even the audience’s apparently mandatory formal wear feels like an absurd joke in contrast to Carmichael’s casual Timberlands and jean jacket on stage.

So perhaps 8’s title is another absurd joke. For an hour of stand-up in which he constantly poses everyday answers to existential questions, it’s fitting that Carmichael chose a name that twists the infinity symbol on its head. It’s an impressive trick.

Dave Maher is a comedian and writer in Chicago.

Chris Christie Belongs on the Radio

He’s the perfect hate-listen for rush-hour traffic.

Chris Christie loves to hear himself talk. Here in Jersey, we’ve been listening to our bombastic, basement-polling governor gabble through 8 years of sprawling press conferences and theatrical town halls. But the end is near. Christie’s term ends in January 2018, and he needs a new job.

He’s already auditioned for one position: sports talk radio host. On Monday and Tuesday of this week, Christie subbed for soon-to-retire talk icon Mike Francesca on New York’s WFAN. Those are not easy shoes to fill. Love him or hate him, Francesca is endlessly entertaining. He’s prone to meltdowns and breathy pauses, but Francesca knows his sports.

Christie’s no slouch at gabbing about sports, either. Despite his responsibilities as governor, Christie has somehow been making regular morning appearances on WFAN’s Boomer & Carton Show, pontificating on everything from the performance of his beloved Mets to the creepily discussing the attractiveness of female tennis stars. He also has a monthly “Ask the Governor” radio show on NJ 101.5, a station that has been traditionally friendly to him. There’s a difference, though, between being a chatty guest and the main radio event.

Monday’s show opened with Christie and his partner Evan Roberts singing the “Mike’s On” opening show theme. Christie joked, “That’s just the beginning of the humiliation.” Roberts, to the pleasure of the entire Garden State, then said “Governor Christie is kind enough to be in the studio, and not at the beach” — a nod to Christie’s decision to spend the July 4th weekend with his family on a closed state beach.

Christie and Roberts then bantered about their shared love for the Mets before turning to the New York Knicks. All was fine until Christie’s geographic nemesis, the town of Montclair, hit the airwaves. First up was John from Montclair, who said he was part of the 85 percent of state residents who don’t like Christie as governor. Christie, who has always hated the Democrat-leaning town, said “you lost twice, John,” and then offered his support for President Trump by quipping that Hillary Clinton is a “criminal.”

Next up was Mike from Montclair, a veteran Francesca caller, who delivered the sports talk radio quote of the week: “Governor, next time you want to sit on a beach that is closed to the entire world except you, you put your fat ass in a car and go to one that’s open to all your constituents, not just you and yours.” Christie called him a communist from Montclair, but Mike didn’t back down, spitting “you have bad optics, and you’re a bully.”

Christie’s comeback — “Mike, I’d love to come look at your optics everyday, buddy” — was a lethargic punch. Although his first day was well-received by critics, that flaccid line was a good preview of Tuesday’s performance. Callers were less combative. The show slogged. Christie even said WFAN “screwed us” by putting their audition on the “two worst sports days of the year”: the dark days of baseball’s All-Star break. Day two is early to be making excuses.

Sports talk radio hosts and politicians have a lot in common; namely, they must be talented storytellers who know their audiences. Christie, at his oratorical best, is pugilistic and hyperbolic before toning it down. It served him well during his first years in office, before the cracks in his stories began to show. In some coverage of Christie’s radio audition, he has been described as the catcher for his state-championship winning high school baseball team — a way to confirm his sports chops. It is true that Christie’s high school, Livingston, won the Group 4 title in 1980, his senior year. But Christie was the backup catcher; a few years ago, the team’s pitcher told The Washington Post that Christie’s parents were “considering consulting attorneys” so that Christie wouldn’t ride the bench. Christie always feels like he’s aiming to even the score, to gain revenge on a decades-old slight.

Christie’s political career is as stalled as traffic on Route 1 on a Wednesday afternoon. Besides being dumped from his post as leader of Donald Trump’s transition team, he hasn’t been offered a job in the administration. Two of Christie’s aides were recently convicted in the Bridgegate trial, and both the defense and prosecution agreed on one point: he created a culture of revenge and shadowy operations during his tenure in office. In the most recent poll, he had a 15 percent approval rating. He’s been an exquisitely terrible governor, and we’re talking about New Jersey, where poor governance crosses party lines.

New Jersey being perpetually mad at Chris Christie is the most Jersey thing ever. Conservatives, liberals, we’re all tired of the empty promises. Our taxes continue to go up, and our services have been slashed. Christie’s an absentee landlord: according to NJ Advance Media, in 2015, when Christie began his ill-fated presidential run, he spent 261 days — 72 percent of the year — out of state. He’s done with us, and we’re done with him.

I wanted to hate Christie on the radio in a good way, in a I’m-stuck-in-traffic-on-the-potholed-parkway kind of way. Instead, I was reminded of when Christie’s penchant for opulent trips and plane rides paid for by others reached The New York Times. He told the newspaper, “I try to squeeze all the juice out of the orange that I can.” That kind of sarcasm used to be endearing to New Jerseyans — until taxpayers realized that they were the ones left dry.

Kllo, "Virtue"

Why would today be better than yesterday?

Did you know men are tucking their t-shirts in now? Every morning I wake up and I think the world can’t possibly have gotten any stupider than it was when I went to bed and yet there is never any shortage of new material to prove me wrong. Anyway, here’s music. Enjoy.

New York City, July 10, 2017

★★★★ The dim and bright moments of the morning each seemed too strong to be chasing the other in such rapid succession. Possibly a drop or two of rain blew down out of the broken patterns overhead. The day had seemed cool at first but the linen shirt started sticking to the skin. The main office window had been washed and the unusual clarity of it added to the increasing sharpness of the daylight. To freshly dilated eyes, the sky outside the eye doctor’s office was a horror, a cascade of greenish molten glass. Tears squirted out and ran down to the tip of the nose on the blind struggle around the corner to the subway. Somehow the tears had gotten up into the eyebrows. On the way back out into the sun, a pair of legs in white pants leading the way up the subway stairs felt as if they were kicking the corneas with each step. The crosswalks were radioactive. By the time it was safe to look out at the sky again, it had gone grimy gray and orange.

You Know What's Better Than Inbox Zero?

Inbox twenty.

Look, it’s me, printing out my old blogs and eating them. Once upon a time I was young and ambitious and had a much shorter haircut and I worked in a skyscraper and I held myself to a pretty much impossible standard. That’s right, I used to do Inbox Zero. I was very good at it, and I managed to keep it pretty much under control across two email inboxes: work and personal.

Now, I have two jobs, three work emails, and a lot more than zero emails in every inbox. I’m ready to admit that a much more reasonable goal is: slightly more than zero, but not enough to require a scroll to a second screen. Ergo: twenty! For me, lately, “twenty” has been more like twenty-five, but today I got down to nineteen. Doesn’t that feel really significant, like turning a corner and breaking through an imaginary wall only I could see to becoming a better person? It does, to me.

The general principle remains the same: file away (archive, not delete) anything that doesn’t require your action. Keep in your inbox only what you need to accomplish (for me: mostly edits, some replies), and sweep the rest under the rug. There, doesn’t your workspace feel neater and more manageable? But I forgot the main principle of work, is that it’s there the next day. You work on it as much as you can, you go home, and you come back, and it’s never finished. Lord knows we will all—each and every one of us—die as we lived: with emails in our inbox. Mine will probably be from Everlane, Bank of America, and the Harvard College Fund.

Admittedly, I am very much still “addicted to the gratification that comes from tidying up,” I just have more reasonable expectations now—twenty instead of zero. Doesn’t that seem more balanced and self-forgiving? It’s charitable, it’s efficient, and it’s just imperfect enough—like a real human flaw. Is this what they call getting older? Or is this just letting go? Don’t answer that.