The Moment When Hillary Clinton Threw Away The Election

Was this it?

Why did Hillary Clinton lose a can’t-miss election to Donald Trump? You can make any number of arguments, including but not limited to: the difficulty of one party winning three straight elections in our modern era, an unwillingness by most observers to acknowledge that Americans could very easily elect a manifestly incompetent buffoon, deeply embedded structural factors which favor land over people, a widespread distrust of the elite classes who have benefited from the modern economy while many have seen their prospects stall or go backwards, the active interference of a hostile foreign power, the unprecedented intervention of a sanctimonious FBI director, the timidity of an incumbent president too feckless to alert the American people to an unprecedented attack on our system, the perfidious partisanship of the Senate Majority Leader in refusing to acknowledge those belligerent acts, the rise and acceptance as normal of a hostile media organization which has had two decades to serve as the propaganda wing of one party while keeping its elderly viewers in a state of fear and agitation wildly at odds with reality and the concomitant rightward shift of acceptable debate, the ostensibly objective “Paper of Record” choosing to overplay one candidate’s “scandals” while underplaying the other’s more obvious issues, recalcitrant purists whose privileged and immature refusal to acknowledge what was really at stake helped to drain enthusiasm and votes from the only left-leaning candidate with a shot at actually winning or the inarguable misogyny that is an inescapable fact of modern life.

Or you could say it was because of this, which happened one year ago today.

Historians will deliberate about the question for however many years we have left, but it’s hard not to see how it didn’t play a substantial role. Happy anniversary.

ZW, "Wulfman" (Alva Noto Remix)

Every cloud has a cloud of its own.

I guess a good way to think about how long every day lasts now is that at least it’s keeping summer from ending as quickly as it usually does. No? You’re not buying it? Well, fuck you. I’m not happy about it either. Jesus Christ, you try to do one positive thing to make people feel better about life and they reject you out of hand. See if I ever look on the bright side again. Anyway, not that you deserve it, but here’s music. Enjoy.

New York City, July 12, 2017

★★ The air was optically clear but thick and disgusting to the touch. The barber’s pinhole shade was opaque from the outside and transparent with the sun coming in. The hot towel was fine but probably the cold one would have been better. A ratty pigeon lurched around, nearly getting stepped on. Walking was a chore; sitting still in the air conditioning was not better. A woman on the sidewalk and people up on a roof deck yelled back and forth across nine stories of space, trying to figure out how she should get up there.

Monkeys Aren't People, Too

At least the 9th Circuit Court of Appeals probably doesn’t think so

In general I like to refrain from predicting how judges will rule, but I feel pretty safe saying that the 9th Circuit will not allow a monkey to sue for copyright infringement.

Sometimes our legal system is both fun and fascinating! Sarah Jeong has an excellent, straightforward, and thorough overview at Motherboard of the “Monkey Selfie” case. The what? I know. Read it. If it were me, I’d give the monkey the copyright just this one time because that smile is perfect, but then again that might set a weird precedent. This is why I’m not a judge. In other monkey trial news, the annual Scopes Trial Festival is this weekend in Dayton, Tennesee, where you can watch a play and then listen to bluegrass music and then head on over to the Monkey Town Brewing Company for some Evolution IPA. Did you know that In addition to being fun, our justice system is great for tourism? The latest debate in Dayton these days is about erecting a bronze statue of Clarence Darrow, the defense attorney in the Scopes trial, because it’s being funded by people who rabidly want to keep bibles out of schools. I just have to wonder: had Naruto been an ape (Hominoidea; Old World tailless anthropoid primates—a superfamily that includes humans) rather than a macaque (Cercopithecidae; Old World monkey), would things be any different?

Economic System Bad

Did you ever think that maybe a relentless scheme of pervasive exploitation might not be the most beneficial arrangement on which to build a compassionate society?

Some days it feels like capitalism senses the game might be up soon so it is trying to destroy everything it can while it still has power, before socialism has a chance to show it can work. But then you realize that capitalism doesn’t know anything: It just eats and shits and eats and breaks and eats and shits some more. Anyway, the best thing on the web this week was this piece from Fast Company, which says nothing new or groundbreaking but makes the simple, elegant case that capitalism is killing us and perhaps we could think of a better way to run things. Read and share.

Are You Ready To Consider That Capitalism Is The Real Problem?

A Poem by Elizabeth Hoover

Potamology

I. Assorted Facts About Rivers

drive southward (except one)

lack relics

follow salt

exist in imagination and myth as well as in mud and mineral

hard to integrate into the mind because of continuity, edacity, deathlessness

when meeting another body, a river welcomes part of that body into its own

this perfect body is known as estuary

risible

II. A Story with a River

One day during rowing practice, our coach yelled, “Hold water,” meaning place the oars vertically in the river to arrest forward motion. Our arms shook with effort as the boat kept drifting toward the bridge topped by police cars. A rope dangled over the edge. Suddenly a diver lifted his otter-slick head from the water and waved. The rope went taut. As we slid beneath the bridge, a body lifted from the river, twisting like a pupa and sprinkling us with water. Later we learned from the coach’s newspaper that the woman had been raped and, when she ran, chased to the bridge. We talked about ourselves — what we would do — and of the river, choppy on account of rain.

III. Relationship to Sky

If overcast, mid-sized waves.

If sunny, depends on the wind.

If light rain, smooth.

If after a hard rain, choppy

and coach kept us on land, doing jumping jacks

in the parking lot and a drill called

prisoner runs. As we jogged past the bridge,

how many of us wondered what the river held?

How many graves does the river make? How many

dream of escape along a river? As our feet bit the gravel

at the edge of the bridge’s shadow, did we ask

was it a jump or a push?

IV. On Mass and Persistence

How does one measure the mass of a river,

mass meaning whether or not you can gather

something in your arms. In that sense,

the river’s mass is both yes and no, if —

as one girl imagines — the woman stretched

her arms out as though greeting a loved one.

She is afraid she will see herself

dangling from that rope. Impossible, she thinks,

I never ran. How did the woman know to run or rather how

did she will herself to move, to kick and fight? Or how

did I not? The girl needs another question, one that will make

a new river, one that will make estuary, a question

I don’t yet have the words for. Instead I will tell you

how 13 horses once stood on the banks of the Bukhtarma crowned

in ibex horns and ornamented with masks of cats and griffins,

all smelted from gold so when the sun rises they shine like

mythical creatures scattering sparks into the dawn-slicked water

where they will be slaughtered, buried with their master, and revealed

millennia later by archeologists puzzling over these adornments and

I will tell you archeologists bore into their bones to study the marrow

so I can run

without seeing the river, or the body lifting, or the men sliding me onto

the gurney, the gurney wheeling away.

Elizabeth Hoover’s poetry has appeared in Epoch, Crab Orchard Review, The Los Angeles Review, and elsewhere. She recently received the Difficult Fruit Poetry Prize from IthacaLit. Her creative nonfiction has been published in Lunch Ticket and StoryQuarterly, as the winner of their 2015 essay prize. She lives in Pittsburgh.

The Poetry Section is edited by Mark Bibbins.

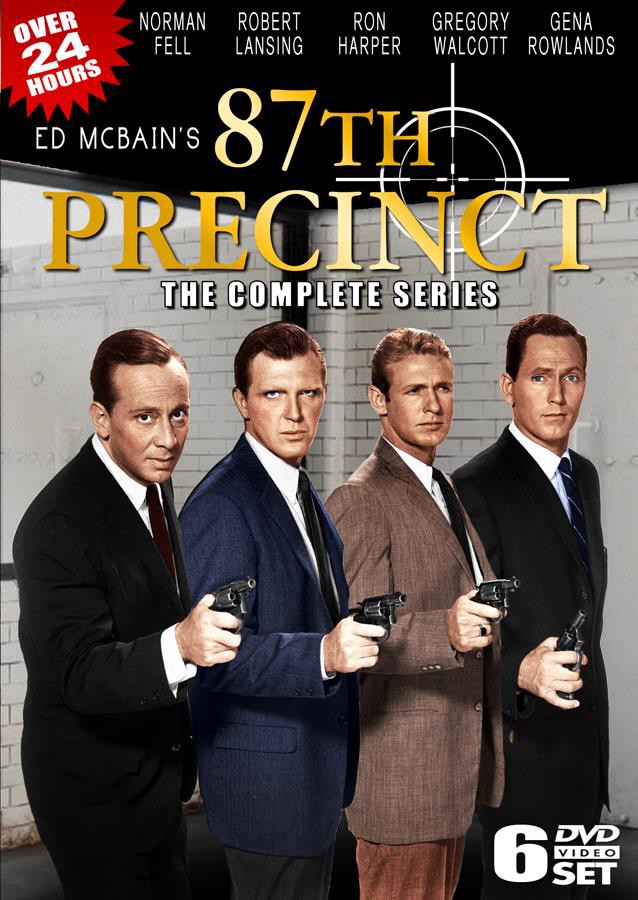

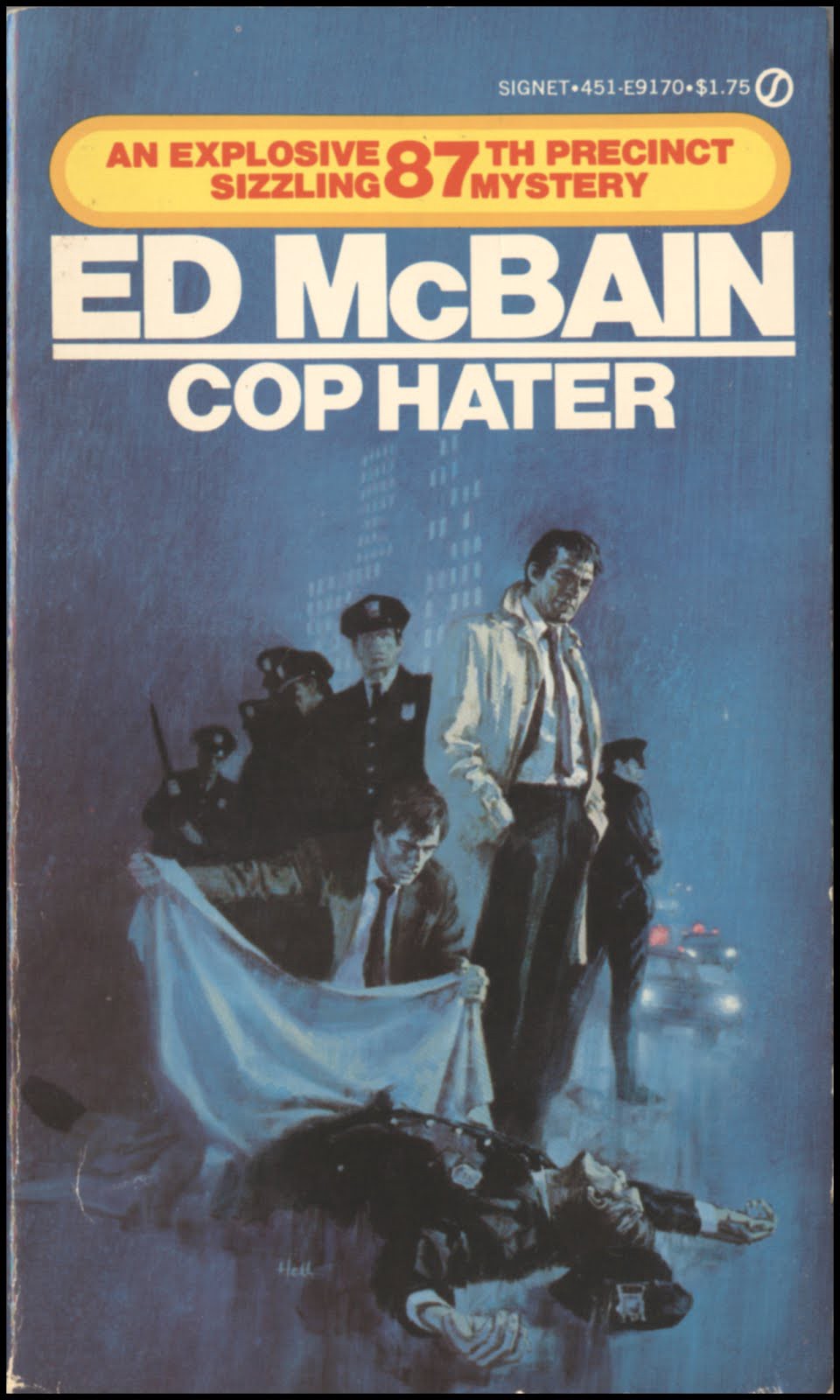

"87th Precinct" (1961-1962)

I once worked with a guy who told me this, with unblinking seriousness, when I sheepishly confessed to liking Metallica: “Metallica deconstructs masculinity.” I wasn’t sure if this was true, but I loved it: it sounded both smart and crazy, seemed dazzlingly counterintuitive, and absolved me of some of my embarrassment by conferring value on the sentence’s somewhat naff subject. In fact, I liked the statement so much that in the intervening couple of decades since I first heard it, I’ve tried to match its latter two words with other unlikely subjects in the art and entertainment worlds. For example, “Evan Hunter deconstructs masculinity.” Sure, it lacks the satisfying crunch of the original, but it has the advantage of being true.

Evan Hunter was born Salvatore Lombino in New York City in 1926 and died in Connecticut in 2005, and in that span he wrote one hundred–odd novels and a clutch of screenplays, most famously The Birds for Alfred Hitchcock. But the books for which Hunter is best known are credited to Ed McBain, whose name you will have seen on the covers of the 87th Precinct crime novels in your dad’s den. Your dad has good taste: the 87th Precinct novels are crisp, funny, and keenly plotted; Hunter was devoted to showing the detectives’ technique, supplying forensics, and not wasting the reader’s time.

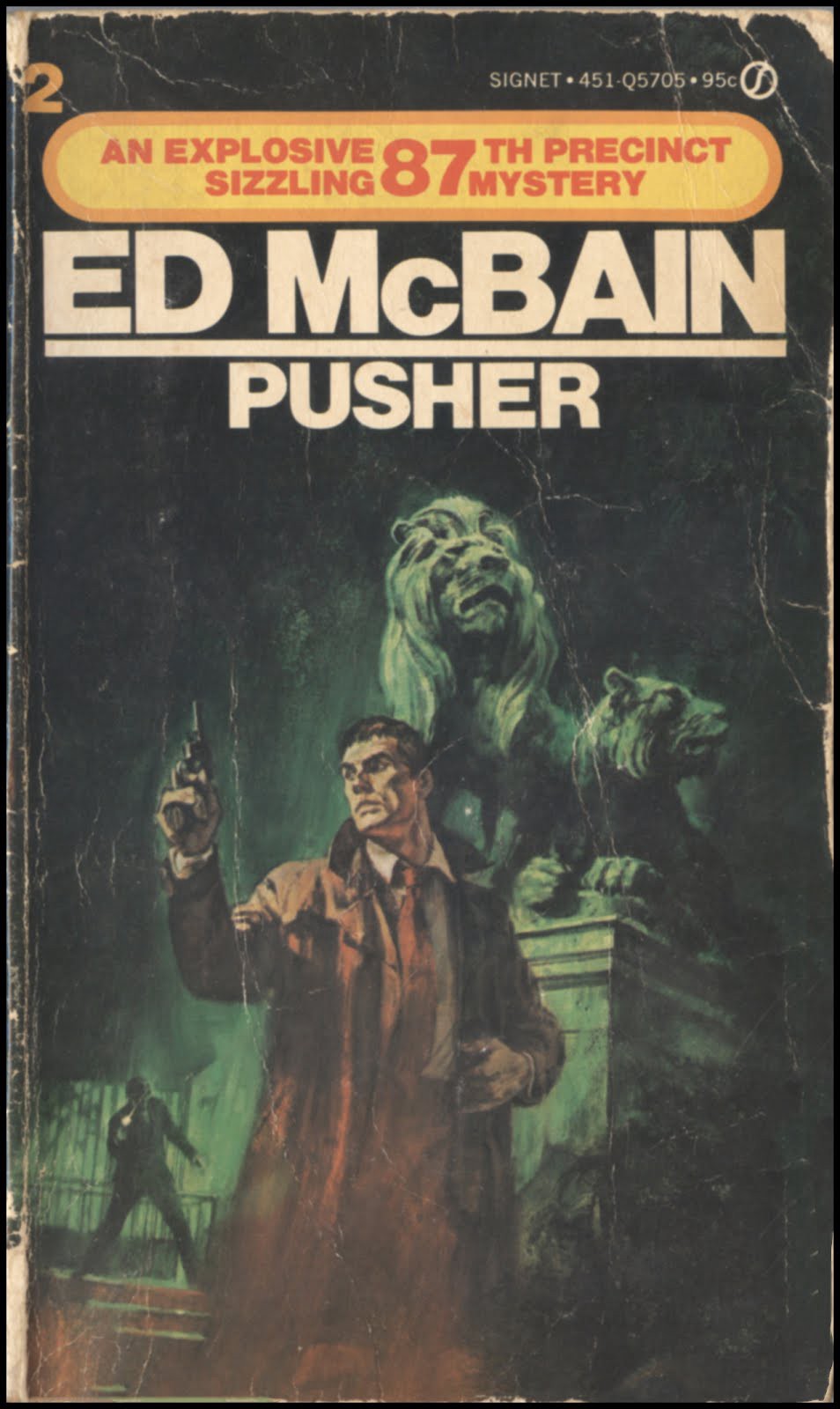

The books are also the basis for a rather marvelous, utterly forgotten black-and-white crime drama that ran on NBC for a single season, from 1961 to 1962. “87th Precinct” doesn’t seem to be streaming anywhere; I got a copy of the DVD through my Boston-area library, which somehow borrowed it from a library in Lawrence, Kansas. Like the McBain novels, “87th Precinct” revolves around a handful of detectives working out of a standard-issue building in a gritty metropolis. Robert Lansing plays the head dick, Steve Carella, in a way that’s hard-boiled but not ossified. (Lansing had practice: he played Carella in 1960’s The Pusher, based on the McBain novel of that name.) Carella’s second bananas are Bert Kling, a young buck played by Ron Harper, whose tutelage under Lee Strasberg served the actor well; Meyer Meyer, the long-suffering family man, played by Norman Fell — Mr. Roper to you if you’re a child of the seventies — who turns in a subtly Jewed-up performance; and dedicated bachelor Roger Havilland (an asshole in the McBain novels but cleaned up for television), played by Gregory Walcott with a Southern accent that — in the series’ only unsolved mystery — keeps disappearing.

The thirty episodes are economical and muscular, and there’s not a dud among them. Some were based on stories by pros like the just-out-of-the-gate Donald E. Westlake, but the most reliable source of material was the 87th Precinct books — Hunter himself turned a couple into teleplays. Given this, “87th Precinct” can’t help but carry the mark of Hunter’s liberalism, made plain in his books and in interviews, which is what transforms the show from a solid crime drama into something a little bit heroic for its time.

“87th Precinct” is almost exhibitionist in its sympathy for the luckless community the detectives serve, made up of kooky old-timers, people with accents, kids playing unsupervised on city sidewalks, and adults on their second chances. You won’t often find the 87th’s detectives rushing to catch a crook at a Park Avenue palace. This precinct was serving — in a phrase that would have made Carella suspicious — multicultural America.

If the pasty, blue-eyed Lansing doesn’t immediately conjure the novels’ pointedly Italian-American star, there’s no glossing over his background in the scripts. In one episode, after Carella meets an older Italian couple — the owners of a burgled shop — he tosses off a line in Italian to gain their trust. In another, he’s trying to get a suspect’s name out of a club owner who says, “It’s one of those long, crazy I-talian names. Seems like it starts with a C,” to which the detective replies, “You mean something like Carella?” In “Occupation, Citizen,” Carella meets with a locksmith — a “Hungarian refugee” — who may be able to identify a perp. When Carella tries to pronounce the locksmith’s name — it’s Czepreghi — the man smiles and says, “I’m going to change it when I get my citizenship papers. I mean, we’re going to have a baby. You can’t hang a name like that on an American kid.” Carella says, “Don’t change it. It’s a good name.” Funny how Hunter, who had adopted a de-ethnicized name, kept his protagonist’s stripes visible.

I-talians, Latinos, and various ambiguously accented characters were joined by Asian characters played by certifiably Asian actors — hardly a sure bet in 1961 and 1962; as late as 1964, Marlo Thomas was cast as a Chinese mail-order bride in an episode of “Bonanza.” At some point while I was tearing through “87th Precinct” episodes, I figured at this rate I might even see a black actor. I racked up several, including a cop played by Bernie Hamilton (later of “Starsky and Hutch”) and an unbearably cute toddler who says “I was robbed!” while sitting on Meyer’s desk, the precinct’s rest stop for neighborhood eccentrics.

When the kid’s parents — a smiling, well-dressed black couple — come to claim their little prevaricator, I became convinced that the team behind “87th Precinct” was informing white viewers, two years before television brought them the March on Washington, that black people were part of their world, so deal with it, you racist shitsacks. Having said that, the lost-toddler-on-the-desk scene also works as a reflection of the show’s commitment to realism. In this episode, a toddler tests Meyer’s patience. In another, Lansing grumbles about breaking in new shoes. Everybody’s home life intrudes on their work. Everybody bitches about their meager paychecks. These short, naturalistic-seeming sequences, all inconsequential to the case up for cracking, offer a level of set dressing anathema to the crime genre at the time. As Ron Harper says of “87th Precinct” in a DVD extra, “It wasn’t Sergeant Friday.”

The nattering among the series’ four principals neutralizes the detective story’s archetypal macho posturing, and at one point the show addresses it head-on. In “Line of Duty,” which Hunter wrote specially for the series, Kling kills his first criminal, and it turns out to be a teenager, which undoes him. A preoccupation with male grief is characteristic of Hunter’s work and the lynchpin in his 1959 novel A Matter of Conviction, at the end of which a troubled teenager’s remark, “Crying is for cowards,” is answered this way by the prosecutor protagonist: “Crying is for men, too.” When Carella tells Kling’s worried girlfriend, “The first time I killed a man I went home and I bawled like a baby,” it splits the seams of his Ronald Reagan–ish rectitude.

“87th Precinct” doesn’t avoid all the tropes of the era. Some judo chops are less convincing than others, and a few of the less seasoned guest stars should have joined Ron Harper in Lee Strasberg’s acting class. But overall, the guesting actors are a welcome procession of favorite midcentury faces, some on their way up (Peter Falk, Dennis Hopper, Leonard Nimoy, Robert Culp, and Gena Rowlands, as Carella’s deaf wife) and one on her way to Washington (Nancy Davis Reagan). By the time John “Gomez” Astin showed up, I thought there weren’t any beloved character actors left, but suddenly, there was a pre–“Beverly Hillbillies” Nancy Kulp, screaming her head off about a corpse.

In the graveyard for shows canceled before their time, “87th Precinct” must have one of the dumbest causes of death. An online source says that its ratings suffered from its being up against CBS bulwarks “The Danny Thomas Show” and “The Andy Griffith Show,” but in his DVD extra, Harper reports that “87th Precinct” had sturdy ratings and ended because its producer, Hubbell Robinson, went to another network and NBC’s pooh-bahs didn’t think the program could continue without him. Harper says he thought “87th Precinct” had years of life left in it, and I agree. Imagine what an Italian-American gent, an all-American boy, a grumpy Jew, and a lapsed Southerner could have made of the decade’s social issues to come, each new challenge parading up the precinct steps and taking a seat in the chair at Meyer’s desk.

In 2010, there was a news item about how Lionsgate TV, overseen by Steve Buscemi and Stanley Tucci’s Olive Productions, was working on something called “87th Precinct.” I’ve read nothing else about the project and can only surmise that it fizzled. For now, the television successor to “87th Precinct” remains “Hill Street Blues.” Hunter, who truly was the father of the modern police procedural, took issue with that show, telling an interviewer in 1998, “I really don’t think ‘Hill Street Blues’ was an homage to Ed McBain; I think it was a rip-off.” He was even moved to consult a lawyer to see if there was grounds for a suit. “Without even a tip of the hat,” Hunter griped. “Had the creators said somewhere that it was inspired by Ed McBain, I’d feel a little better about it.” Jeez, what a crybaby.

Nell Beram is coauthor of Yoko Ono: Collector of Skies and a former Atlantic Monthly staff editor. She writes occasional Best Forgotten columns for The Awl.

Is Franz Liszt in Heaven or Hell? An Investigation

I never got the opportunity to play Franz Liszt in my years as a musician. My introduction to him came through literature — through one of my favorite books when I was in high school, Neil Gaiman and Terry Pratchett’s Good Omens. The book details a relationship between a slightly well-intentioned demon and a mischievous angel during what might be the apocalypse. The two are very into music, and early in the novel, they have the following exchange:

“We’ll win of course,” [Aziraphale, the angel] said.

“You don’t want that,” said the demon.

“Why not, pray?”

“Listen,” said [the demon] Crowley desperately. “How many musicians do you think your side have got, eh? First grade, I mean.”

Aziraphale looked taken aback. “Well, I should think — ” he began.

“Two,” said Crowley. “Elgar and Liszt. That’s all. We’ve got the rest. Beethoven, Brahms, all the Bachs, Mozart, the lot. Can you imagine eternity with Elgar?”

Aziraphale shut his eyes. “All too easily,” he groaned.

So Liszt is boring, I assumed. Virtuous. It’s insane that my teenage mind skipped right over the mention of Elgar, if only because at the time I was reading this book, one of my crushes was in the midst of learning one of the composer’s cello concertos. (We’ll get there in this column one of these days, when the wounds of my broken teenage heart have healed.) But this turned me off of Liszt for a good amount of time, and I continued not to ever play his works through no fault of my own.

I didn’t really encounter Liszt until I dove into Brahms this past winter. Liszt and Brahms had a deeply tumultuous relationship with each other, which was yet another minus on Liszt’s side for me. During the same time that Brahms was a young upstart composer, Liszt was sort of the godfather of the game. He collected allies in the scene, ranging from Berlioz to Saint-Saëns to Wagner. He had really perfected the symphonic poem, as well as embraced the responsibility and ownership over nationalistic music. Keep in mind, Liszt lived from 1811 to 1886, so this is a long time before composers like Dvořák or Janáček would embrace similar sensibilities.

Also Liszt was maybe an anti-Semite? Or at the very least, he at one point suggested that Semitic people have no “genuine creativity.” Lol uh? So maybe he doesn’t go to Heaven?

This week’s piece is his Hungarian Rhapsody №2 (recording done by Arthur Fielder of the Boston Pops, who you’ll remember as being 100% responsible for tormenting the ghost of Tchaikovsky). It’s widely used in pop culture. You may know it from the Marx brothers’ work or from “Looney Tunes” or “Animaniacs.” It plays an odd part in a bizarre Hungarian film called White God. It’s “around,” as they say.

What is Hungarian Rhapsody №2 precisely? Well, it was an orchestral adaptation of a piano piece that Liszt first composed in 1847, eventually publishing in 1851. And what is a rhapsody? Well, it’s a piece of music that takes on an indefinite form. So this is a very non-traditional sounding composition, even though it takes its roots in Hungarian folk music. It opens with a section called the lassan, a dark and stately theme. And dark and stately it is! I remember first hearing this piece and having this sort of sinking feeling. Thinking I knew exactly what it was going to be, and knowing, deep down, I didn’t want to bear the darkness of it. And yet, its opening refrain is not so unlistenable. It doesn’t turn you off, it just bears on you. That is, until, the clarinet cadenza around the 1:18 mark. There’s something playful there, something unknown. It’s a wink, no doubt, that something different is to come.

From there, the woodwinds take control for a bit. The piece pulls itself out of itself. Suddenly it livens up, starts to bounce a little. This is not the piece you thought it would be at its very beginning. Even when its opening theme reprises itself about 3 minutes in, there’s a buoyancy to it. Its stateliness was a facade.

And THEN! One of the absolute best things happens! You have no idea, but BAM, right at the 5:24 mark. Liszt lures you into a false ending, but no, he’s just changed directions. This, my friends, is the friska. It’s the fast part. And boy, it flipping races. It speeds up so arrogantly that you can’t help but respect the shit-eating grin nature of this type of escalation forward. Liszt has everyone going: the woodwinds, the strings, the low brass. And then when he hits the 6:04 mark, just when you think it’s going to race out of control, he brings out the crash cymbals and balances it back out again. Now we’re having fun, and you almost don’t care that he maybe hated Jews (just kidding — we DO care and it IS bad).

There are so many pleasant fucking touches in this second half. I love this part at the 6:59 mark where it occasionally sounds like the strings’ bows are just sliding all the way off of the instrument. Even the TRIANGLE is going insane. I’m not kidding at all. I wouldn’t joke about triangle. Listen to that part at 7:27. It’s just ringing and blaring as loudly as that little and occasionally awful instrument can go. This is not music composed by some boring heavenly rule-follower. It’s cocky! It’s disorienting! Liszt is not dull by any stretch of the imagination. There’s power and seductiveness to his writing, and it almost makes you think that maybe, just maybe, he’s in Hell with the rest of the good composers.

Fran Hoepfner is a writer from Chicago. You can find a corresponding playlist for all of the pieces discussed in this column here.

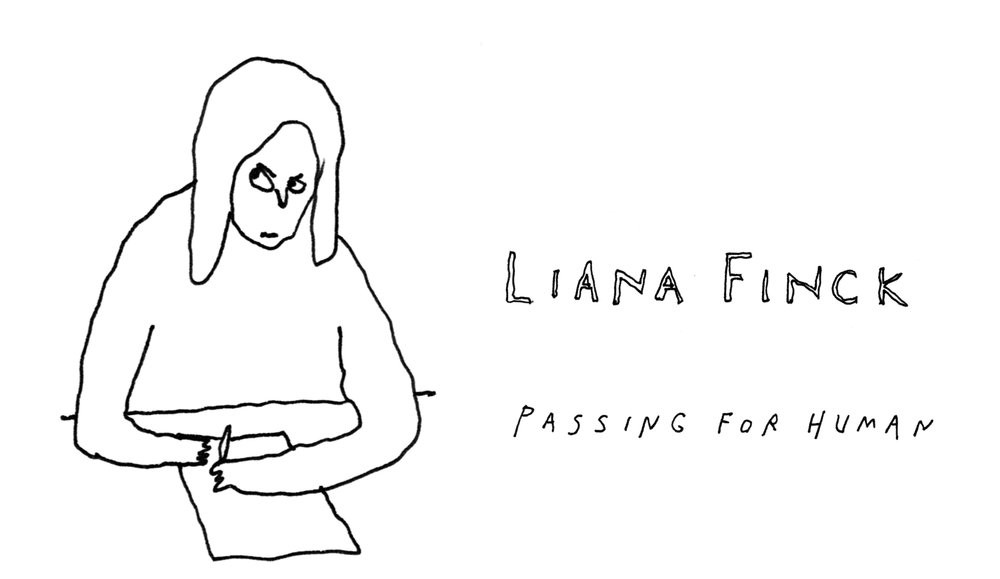

Passing For Human

Liana Finck is having a gallery show on the Lower East Side, and you should go.

One of the best things that has happened to this website since I’ve been at the wheel is Liana Finck gracing it with her pen. She is a cartoonist for The New Yorker, and the author of A Bintel Brief: On Love and Longing in Old New York. If you enjoy her work—so razor-sharp it stings—her prolific Instagram is a must-follow. She is a little like the Roz Chast of my generation, if possibly more sui generis—darker, and with sharper teeth.

Starting next week, she will have her first solo exhibition, at the Artists’ Equity Gallery in downtown Manhattan:

Liana Finck, Passing for Human

July 19 — August 5, 2017

Curated by Melinda Wang

Equity Gallery, 245 Broome Street, NY, NY 10002

Opening Reception: Wednesday, July 19, 6–8pm

Gallery Hours: Wednesday to Saturday, 12–6pm, and by appointment