Lafayette Avenue, Brooklyn

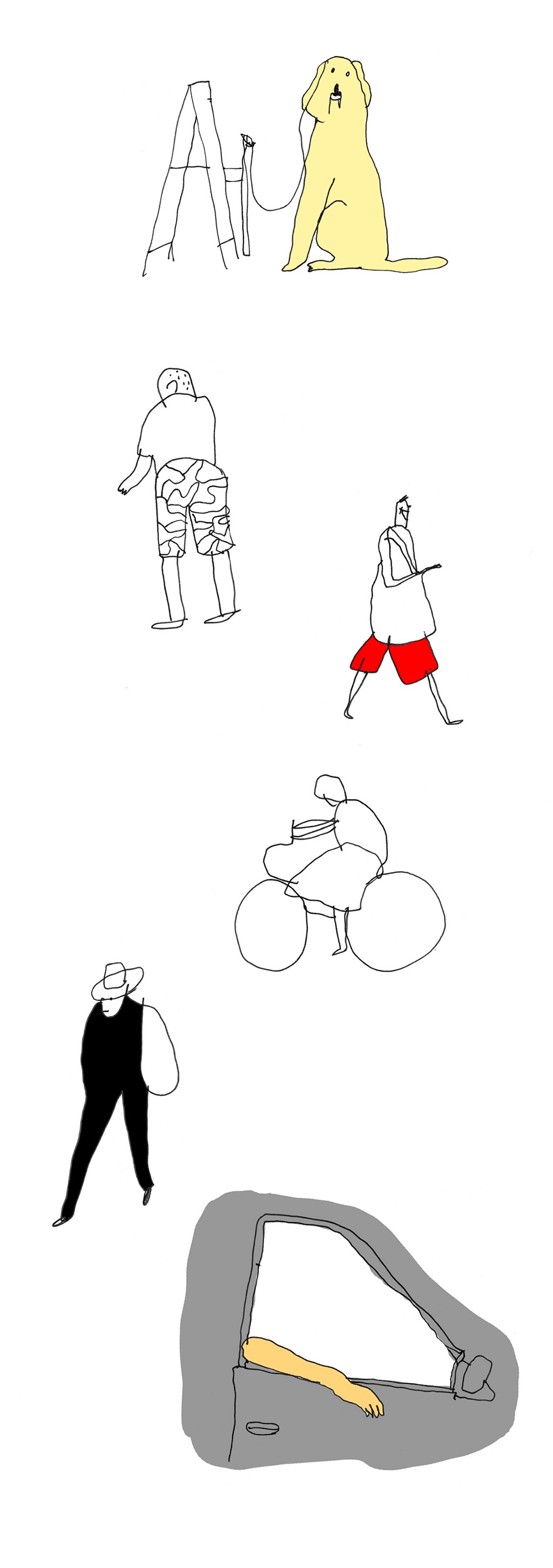

Illustration: Forsyth Harmon

I will forever hold wearing a sailor dress to Molly Warren’s ninth birthday party as one of the great humiliations of my childhood. The mortification at realizing every other girl was in tracksuit bottoms, or jeans, or some other variant of ‘clothes to climb trees in’, was not so much one of failing the party’s dress code, but failing my own. I was not a sailor dress sort of girl. I was a tree climbing sort of girl. But here I was, a travesty of myself, in Laura Ashley knockoff navy polyester and white ribbons and I would be climbing no trees. It was the first time I’d known the specific, painful effort of having to go on as if this were the outfit you’d intended, of having to will an armor of dignity, as if this were really you.

When I saw you out the window of the cafe, you looked how I felt at Molly Warren’s ninth birthday party. Not a sailor dress, but a transparent sugar-pink slip through which wide areolae announced themselves completely. Each New York summer I have this same, abrupt realization of breasts — specifically, how it is that braless ones shivering about beneath thin fabric look both brazen and vulnerable but most of all, just very there. Each New York summer I wonder, is this what it’s like to be a straight teenage boy? To be permanently slightly hostaged by a part of the body? And each New York summer I remind myself that public female toplessness has been legal in this state since 1992.

You were in your early twenties and your outfit was an ironizing cute. A nylon dress that looked like a babydoll nightie from the Seventies, peroxide blonde hair, much eyeliner. You reminded me of Courtney Love in the 90s: the little dresses and their frills and collars a mockery of docility and sweetness, there to signal a bad girl in good-girl drag. (“Oh make me over/I’m all I wanna be/ A walking study/ In demonology.”)

The most conspicuous thing about you, though, wasn’t your clothes. It was your self-consciousness — like you hadn’t decided what the story of yourself was today. Or, that you were telling yourself one, insisting on it, but just couldn’t make it fit. You’d been determined to be this person in a see-through dress in the hot afternoon, and you’d left the house and now I could still see the determination in you: the very upright posture, the flexion of your lips. I thought of that bit in Four Quartets: “the look of flowers that are looked at.” You looked like a girl who was looked at.

You paused outside the cafe, looked at your phone, then came in and ordered an iced coffee. But, as if admitting that you couldn’t sustain it, this story of yourself, you were gone after a few minutes. There’d been a hunted look to you, as you gulped your drink, like someone was watching you, which I was. And then you left, and I knew you were absolutely going home to change. If I could have silently transmitted this to you, I would have: that in ten, or even five, or even two years, you’d look at a picture of yourself in this same outfit, on this same day, and marvel at how good you looked and why it was you hadn’t believed it.

> Crab juice, a fear of heights, Dad day.

From Everything Changes, the Awl’s newsletter. Subscribe here.

Last week, I asked how you knew you’d found your person. You can find all your lovely responses in this spreadsheet, with a small haphazard selection below.

In addition to being wonderful stories, a lot of these are nice ideas for how to show a friend or a partner you love them. Thank you to everyone who wrote in.

We met in primary school aged 6. I had just moved from France and didn’t speak English. I saw her in the playground with the longest, skinniest legs, wearing stripey tights and I knew I wanted to be her friend. Louise and I are still friends now aged 50. — Anne B.

I had one of those ill-fitting bras on — where the whole thing slides around even when you’re sitting still. All day I whined about it to him on gchat, probably layered thick with complaints about the patriarchy generally. When I got home I immediately pulled it off, and he handed me scissors so I could snap it in half and make sure no one would ever suffer it again. Then, slowly and without talking about it, we each took one cup, put them on our heads like party hats, and danced around the kitchen.

What I’m saying is we celebrate each other’s victories.

I knew when he taught me how to eat stone crab. He got crab juice all over his nice sweater and still had a smile on his face. The smallest gestures are the most important, at least to me. — Courtney G.

I knew that L was the person I wanted to be with the rest of my life when we were climbing down from a hike in upstate New York and the fear of heights that I had been trying to fight off took full hold of me. He held my hand for 2 hours’ slow going as I cried and moaned and said things like, “leave me here, just leave me here.” He didn’t let go unless I asked him to, and never once showed anything but understanding and care that entire time. When we got down to the bottom of the mountain and the trail was flat and wide, I was a rubber-kneed mess. He just hugged and kissed me and said that I did a great job. He exhibits that kind of patience and love every day. It’s the rarest thing I’ve ever encountered.

I didn’t. I don’t. But they’ve been the person I wanted to be with tomorrow for nearly 22 years now. That’s good enough for me.

I knew the person was my person when I broke up with my last girlfriend. I’m diagnosed bipolar type two and for the time being have come to the conclusion that I won’t be able to have a stable relationship for the foreseeable future. The swings in emotion are too much for another to deal with and the initial honeymoon period is too intense to claw our way back from. So I realized I was my own person. — Rob R.

I first began dating my now husband back in the fall of 2008. It was only a couple of years after my father had passed away from lung cancer and the anniversary of his death was particularly difficult in those early years of heart aching loss as one might imagine. I warned him when the date was nearing because I wouldn’t be myself in the undertow of sadness that would take me. Fast forward a couple of years into our relationship, we had moved in together and shared our Google calendars with each other to make making plans and tracking things easier for the both of us (I would make plans without consulting him or have dinner with friends and forget to tell him and he’d have no idea where I was…whoops!). I was scrolling through into June to make some camping reservations and came across a note on June 26th on his calendar. He had made a note that just had my name and the words “Dad day”. That’s when I knew he was my person. He had marked down my sad day to be there for me. He has shown me in the almost 9 years we’ve been together so many other thoughtful ways he cares about me, but that was the moment.

Life works when he is around.

My partner and I were in university and had only been dating for a couple of weeks when we woke up in my apartment one Saturday morning. Still sleepy, he got out of bed, walked over to the clothes horse in the corner full of my drying clean clothes, and without warning picked it up and did the best, loudest, most wholehearted horse neigh and head shake. It was so unexpected and so, so funny. Right then I knew — if this guy feels this comfortable being weird and silly with me after only a couple of weeks, he’s my person. That was 9 years ago, and he now does his horse impersonation (among others) for me on request. — Kate N.

My senior year of college I lived in an apartment style suite with 5 other women, 2 I barely knew. The first week, all of us went to Target and I bought a cookie sheet and some cookies dough. We got home, everyone disperses into their rooms while Barely-Know Roommate and I make the cookies to share with everyone. We eat the whole tray ourselves. We go get more cookie dough quickly so the other roommates won’t realize what happened. We make the second batch, get it out of the oven, and close the kitchen door and start to again eat all the cookies ourselves. Another roommate walks in and catches us, we offer her a cookie clearly out of obligation, she leaves, and Barely-Know Roommate and I finish the second tray and instantly are bonded for life.

I knew my husband was a strong contender when he demonstrated flawless knowledge of every bad movie Nicholas Cage has ever been in. I absolutely wanted to be with someone who could appreciate a terrible wig and a nonsense accent.

Our second flying vacation together. The first flying vacation we took together was logistically smooth, but was plagued with constant fighting. Our second flying vacation was a nightmare on paper. We had flight delays going both directions, issues getting to and from the airport, transit problems all over, and we both forgot to pack important things that necessitated a boring store trip as the first task of our fun vacation. To top it off, I got horribly sick from (probably) food poisoning halfway through and spent the back half of the trip ill in the hotel room. Because I was sick, we had to cancel two planned adventures, one of which my person was particularly excited about. But we both kept being kind at each other, and kept all our stresses external, and focused on having fun together. Every time I talk about that vacation, no one listening understands why I look so happy, because it sounds so terrible, but it was the point where I realized that we were completely on the same team. — Michelle J.

I have had two persons in my life; my late husband, and my best friend. I met my best friend one day in college; I hardly knew her, though I knew of her. For some reason, she wandered into my dorm room one afternoon, and burst into tears. She’d just had an abortion. I remember that I looked at her and thought, she’s my best friend forever. It was like a thunderbolt. She says something similar happened to her. We later discovered our dads had gone to the same high school in Cleveland, and that she and I had been born in the same hospital in Columbus, two months to the day apart, even though I then moved 2500 miles away from that town. We now work together and have for ten years. I think we’ll probably form a commune in Maine in twenty years and be together till the end.

My late husband…well, I was in Chicago, and struggling with whether to move to New York. I liked Chicago and didn’t want to leave, but my boyfriend at the time really wanted to go. But I woke up one more morning and just knew: If I move to New York, my life will change. So I did, and eighteen months after that, I got a call from a man named Peter, who needed to make a hire at his newspaper. We met at Grand Central and while I didn’t yet know he was going to be my husband, while I wasn’t even especially attracted to him physically, I was crazily attracted to him as a human being. I came home that night and told myself: I have to find a way to work for this man. I did. Two years later we were together, and we belonged to each other for 17 years. He died four years ago. His last week in the hospital, he held my hand and said, “You’re my person.”

She always looks back when she leaves. Always. — JPS

From Everything Changes, the Awl’s newsletter. Subscribe here.

Weval, "Metazoa"

How come there’s no version of “brr” for hot weather?

It’s hot. Here’s a new one from Weval, which will be featured on the next edition of Kompakt’s Total compilation. Enjoy.

Bethany Beach, Delaware, July 19, 2017

★★★ The ocean was pale and it was breaking where the soft sand gave way to coarse bits of shell. An incongruous band of cool, delicate purple separated the glaring blue of the sky and the glaring blue of the sea. The white crowns of ospreys shone as they slowed to a near-hover, tracking the fish. Dolphins dolphined once again. Both children allowed themselves to be knocked down by the waves, and came home with swimsuits full of sand. The afternoon sun bounced off the sidewalk and made the more western eye sting. A big, heavy charcoal-gray dog loped along through the street and into the yards with no more energy than she needed to stay away from the people converging on her and begging her to let herself be caught. The five-year-old rode his rented bike back from the shop in the somewhat greater shade of the street closest to the ocean. After dinner, he took it out to ride in the street, and the adult helping him roll it out caught a light blow to the head, with the weight and unexpectedness of being struck by a bird dropping. A pattering sound came from the leaves of the sycamore and the roofs of the cars—fat, widely spaced raindrops were falling in the clear low sun. A woman walking dogs and a skateboarder were equally surprised by the ambush on their plans for the last daylight. The boy paused briefly, then went ahead with his bike riding. It was impossible to take the shower as real, even as it dampened the shirt and dappled the pavement. Eventually, but not quickly, it went away and the evening once again became what it had looked like all along.

Gentle Reminder

Because whether you want to or not, you will be typing this name a lot in the next 24–48 hours.

It’s Lana Del Rey, not Lana Del Ray.

The Politics of Pride in Brighton Beach

Challenging homophobia in Russian-speaking Brooklyn

Artem Nevinchanyi is a striking figure: tall and rail thin with olive skin and haunting green eyes that have a piercing seriousness rarely encountered in a man his age. In 2005, when Artem was a seventeen-year-old living in a small Siberian city, he spent winter break visiting his older brother, Denis, in Kaliningrad. The two were on their way home from celebrating the Russian Orthodox New Year in a cafe when they were attacked by three homophobes on a bridge. Denis, a large, fit man recently discharged from the army, was the only person at the time to know Artem was gay. He tried to protect his brother, ordering him to flee the scene. Artem ran to call the police. The following morning, Denis was found dead. That day, Artem not only lost his sole confidant, but also his parents, both of whom continue to blame him for his brother’s death.

Five years later, Artem moved to Moscow, where life as a gay man was easier than it was in Siberia. But, the situation soured for him there, too. In April 2015, three men followed him home from a gay nightclub and beat him senseless in front of the lobby to his apartment building, screaming, “You’ll die here tonight, faggot.” He escaped with a broken nose, broken ribs, and several hematomas. He went to the hospital, where he had to file a police report, but the Moscow police refused to record the incident as a homophobic hate crime. Two weeks later, he got on a plane to New York, where he is currently seeking asylum.

As most asylum seekers do, Artem arrived in the U.S. with neither working papers nor English language skills. Because of this, he had to seek employment in the Russian-speaking areas of South Brooklyn. But the community was not welcoming — at his first job as a discount store clerk in Brooklyn’s Kings Highway, customers frequently uttered gay slurs. When he started working as a bus boy at a cafe in nearby Manhattan Beach, he soon had to quit because of snide remarks and emotional abuse from a homophobic manager. Though the owner of the cafe is gay-friendly, Artem decided to keep quiet about why he was quitting. “I know he [the owner] wouldn’t have fired her. He would have talked to her and it would have just made things worse,” he told me. “And then I would have had to run into her in the neighborhood — it is not a large community, and I prefer to maintain good relations.”

Artem is not alone. Many Russian-speaking LGBT people escape horrific events in Russia, only to encounter employment discrimination, housing discrimination, and sometimes even physical abuse in Russian-speaking areas of New York. And many of them stay silent about these incidents. According to Lyosha Gorshkov, co-president of RUSA LGBT, a Russian-speaking American group, LGBT asylum seekers are afraid to report homophobia not only because of their uncertain legal status, but also because their past experiences in Russian-speaking countries have left them with an acute fear of law enforcement.

This fear has intensified with the election of Donald Trump, who ran on an anti-immigrant platform, appointed the least LGBT-friendly cabinet in recent history, and eliminated the LGBT page from the White House website during his first week in office. In mid-March of this year, Denis Davydov, a gay, HIV-positive asylum seeker from Russia, was detained on his way back from a trip to the U.S. Virgin Islands and held for five weeks at an ICE detention center in Miami. “Asylum seekers travel within the U.S. all the time and there had never been such a case before the current administration came to power,” Artem said. “This really frightened our community.”

In order to protest the policies of President Trump, whom New York’s Russian-speaking neighborhoods overwhelmingly supported in the election; to challenge homophobia in Russian-speaking areas; and to commemorate the recent abductions of gay men in Chechnya, RUSA LGBT held the first-ever pride parade on Brighton Beach, the largest Russian-speaking enclave in Brooklyn. On a rainy Saturday in late May, around three hundred people marched down the boardwalk carrying handmade signs and chanting slogans like, “Brighton, Brighton, we love you! Trump and Putin, bad for you,” and “Queer immigration, benefits the nation!” Artem, waving a giant rainbow flag, led the procession.

Three hundred people at a pride parade may not seem like much, but it was a feat to convince so many Russian LGBT people to march for their rights in a conservative, Russian-speaking neighborhood. Pride parades have played a pivotal role in U.S. LGBT culture since 1970, when thousands marched to commemorate the Stonewall riots in New York City. But in Russia, they never took off. In spite of numerous attempts to orchestrate pride events, it was rare that more than a few dozen people showed up to march.

Sex between men was illegal in the Soviet Union for nearly sixty years, from 1934 until 1993, and highly taboo between women. The lengthy period of stigma has left deep homophobic roots in Russian society, even after the repeal of the law, and many LGBT people have remained closeted. For this reason, the Russian LGBT community has been divided about the efficacy of such public actions. The Russian authorities have tried hard to prevent them, including instituting a 100-year ban on pride parades in Moscow starting in 2012.

In 2013, the State Duma (the Russian legislative assembly) passed a law prohibiting the “propaganda” of “nontraditional” sexual relations to minors. This has created an atmosphere of impunity, resulting in severe spikes in homophobic crimes, and causing large numbers of Russian LGBT people to flee the country. Many of them end up in New York, a gay-friendly city with one of the largest Russian-speaking populations in the U.S. But, New York’s generally liberal attitude toward LGBT people doesn’t always apply to the Russian-speaking areas where asylum seekers tend to live and work. Surrounded by Russian speakers, many are haunted by past traumas, and often have trouble shaking their own internal homophobia. When RUSA LGBT’s Gorshkov first proposed the idea of a pride parade in Brighton Beach at a RUSA meeting in 2015, very few were interested. “Why should we march in there?” people asked. “Why would we put ourselves in the spotlight?”

The election of Donald Trump both angered and frightened members of RUSA LGBT, and motivated Gorshkov to revisit the idea that had been rejected by his compatriots the year before. At a twenty-five person RUSA meeting the week after the election, Gorshkov again proposed a parade. And, once more, the response was underwhelming — only five members were enthusiastic. But this time, the parade’s proponents pushed harder. “I did not come here to lie about who I am,” said Elvira Brodskaya, a thirty-five-year-old redhead who had fled St. Petersburg with her wife after being terrorized and stalked by neighbors and emotionally abused by family members. “So, I really wanted this parade to happen.” She experienced both housing and employment discrimination from the Brighton community, and was perturbed to learn that there were places even in New York where she felt unsafe exposing her true self. Over the next few months, she and other supporters, including Artem, worked tirelessly to garner enthusiasm for the event.

That December, a Russian asylum seeker named Aleksandr Smirnov, who worked for a small Russian-speaking supermarket chain in Sheepshead Bay, faced repeated threats and physical attacks from a homophobic colleague. He reported the incident to the supermarket’s management, but they failed to take action and, in fear of his safety, he quit. Smirnov, who posted about the incident on his Facebook page in January, became the first member of the Russian-speaking LGBT community to go public about homophobia in Russian-speaking Brooklyn. According to Nina Long, co-president of RUSA LGBT, and one of the organizers of Brighton Pride, the incident resonated. “It really hit home that you live in New York but at your place of employment in Brooklyn you can be powerless,” she told me. With Smirnov’s story out in the open, people felt they had something concrete to rally against. In late March, the parade’s supporters had gathered enough willing participants to set a date.

In early April, the Russian independent newspaper Novaya Gazeta, broke a story about the mass abductions and torture of gay men in the Russian Republic of Chechnya. In the weeks leading up to the parade, more than three hundred people signed up to join, including members of the U.S. LGBT community. Gorshkov was invited to speak about the parade on RUSA Radio (not related to RUSA LGBT) and, though he faced the expected homophobia from listeners calling in — some listeners referred to the LGBT community as “sick people,” others said it was shameful to talk about LGBT issues on air because children might hear — he also received some positive reactions. And, according to Long, RUSA received encouraging notes from members of the Brighton community itself, including the proprietors of St. Petersburg Bookstore. “They reached out last year and said, ‘pride is coming, how can we help?’” said Long.

On a chilly, intermittently drizzly Saturday morning in late May, people with flags, signs, and pink triangles commemorating the victims of the antigay purges in Chechnya, gathered in the boardwalk pavilion at Ocean Parkway. Gorshkov, who rushed about preparing the group, worried that the weather would stop people from coming. But, the crowd of marchers kept growing, and by the time I saw Artem, carrying a rainbow flag with U.S. stars, the rain had stopped. Artem was exhilarated by the crowd, and optimistic about the day to come. “We haven’t seen any homophobic incidents yet,” he said. “And that is a good sign.”

On the boardwalk, where marchers had started to gather into formation, protected by thirty members of the NYPD, I met a man named Roman Savrasov. A recently arrived thirty-year-old from St. Petersburg, Savrasov was nervous about his first public LGBT event. “I know everything will be ok,” he told me. “But I can’t help feeling nervous. Especially with so many police around.”

There were not many onlookers. A small, elderly woman in a bright blue jacket told me in Russian, with a dismissive wave, that she didn’t know anything about “these issues,” then asked me why there weren’t more costumes. “I went to the parade in the West Village once and they had people dressed as Elvis!” Naum Portnov, a fifty-seven-year-old emigre from Odesa who was sitting and reading on a boardwalk bench, told me he was looking forward to the parade. “Why not?” he asked. “At least these people can think for themselves, unlike everyone else around here.”

In front of the restaurant Volna, a waitress in her forties, who told me her name was Lena, shook her head in disgust. “This is an abomination,” she said. “How dare they come here and do this. It’s not normal. They need help.” An older waitress — Lena’s aunt — stood by the entrance and urged her niece to calm down. “This is awful,” she said, gesturing at the parade. “But thank god our family is fine. Everyone has kids, I have grandkids, and we’re all normal. That’s all that matters.”

Down on the boardwalk, I overheard a conversation between an octogenarian and his fifty-something home attendant. “Kakoi uzhas,” they muttered (“how awful”) and gestured toward the parade. I stopped them and asked why they were so angry. “Love is between a man and a woman,” the woman told me. “And these people should all be locked away.” She asked me what I thought about the event, and, when I told her everyone should have the right to express themselves, she sneered and asked me, “What, are you a homo too?” then stormed away, plopping down on a nearby bench. “See how much you’ve hurt her?” said the octogenarian, leaning on his cane. Then, he softened. “I don’t agree with all this, but they should be able to do whatever they want.”

The more people I asked how they felt about the parade both during and after the event, the greater the range of opinions I encountered. Many of the elderly people — those who can seem like they never left the Soviet Union — supported LGBT rights. “It’s important to remember that attitudes in Brighton are mixed,” said Long, emphasizing that forty percent of Brighton had voted for Clinton in the election. “It’s insulting to the people who do respect us, to throw them into this pile of bigoted Russian-speakers in New York. That’s why we feel empowered. We’ve seen good here, too.”

Most striking though, was that the majority of Brighton residents who spoke enthusiastically of LGBT rights were also staunch Trump supporters. Misha, a small, smiley Ukrainian man in his sixties, had come to Brighton thirty years prior, and expressed such strong enthusiasm for Trump that it poured out of him completely unprompted. “The great thing,” he told me, after explaining how happy he was that there was freedom for everyone, including gay people, in this country. “Is that we have President Trump. He supports gays, and he’ll let everyone be who they want to be because this is America!” I challenged him, reminding him about the views of Trump’s cabinet, and the removal of the LGBT page from the White House website. But he dismissed my points with a wave of the hand. “It’s no problem,” he told me. “He’s doing things the right way. He said he has no problems with gays, and other minorities in this country,”

As I neared the end of the march route, at Brighton 15, a rally had started. Brodskaya took the microphone, her red hair waiving in the wind, and told the story of how she and her wife had come to the States. Roman Savrasov, the anxious young man I had interviewed at the start of the parade, was in the crowd beaming. “I’m so glad I did this,” he told me. “Everything was so peaceful; my anxiety is gone completely.” Artem was thrilled, too — the march had gone swimmingly, there were no violent incidents. “My only worry,” he told me. “Is what will come next. What will happen in the neighborhood after the parade, once the police are gone?”

Masha Udensiva-Brenner’s writing has appeared in Guernica, New Republic, and Tablet, among others. She is the host and producer of Expert Opinions, a podcast on Russia, Eurasia, and Eastern Europe, on EurasiaNet. Follow her on Twitter at @MashaUBrenner

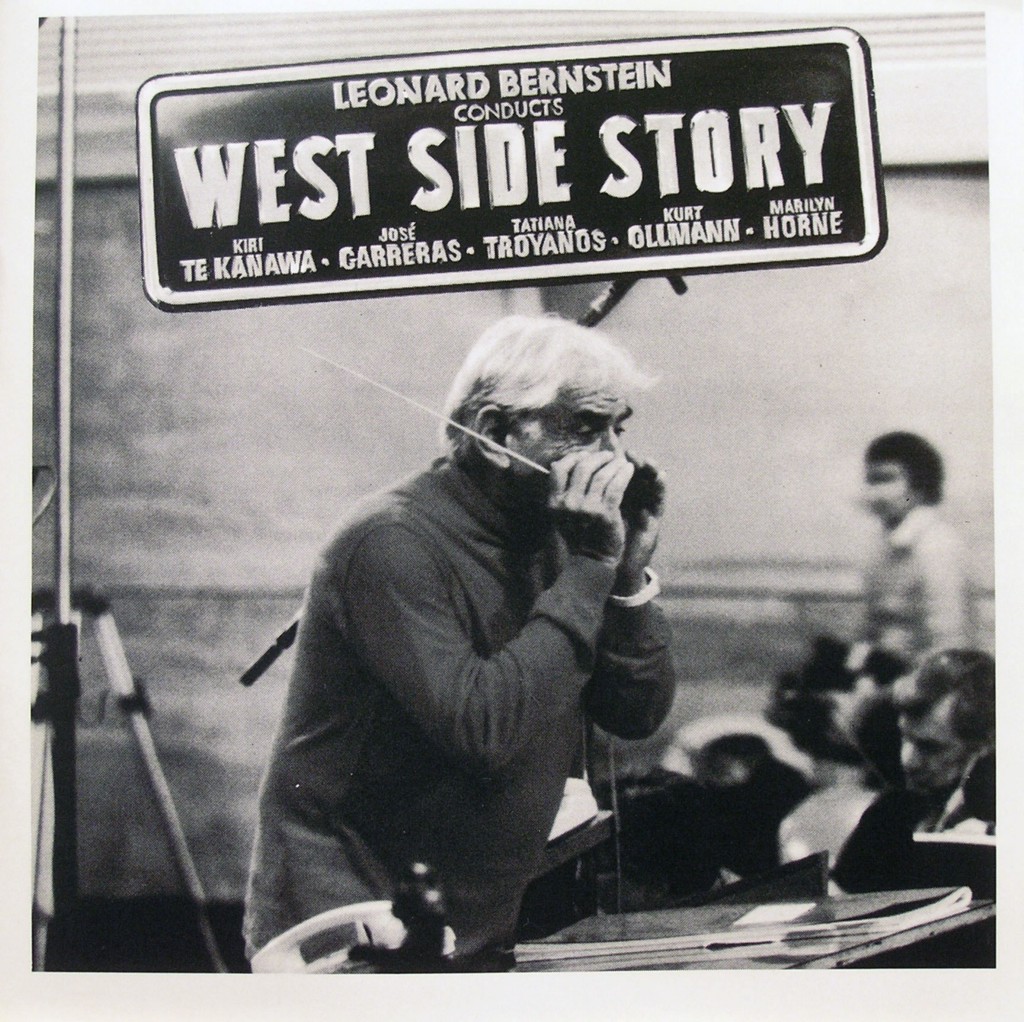

When Was The Last Time You Listened To 'West Side Story'?

Week after week, I share my preferred recordings of the pieces I write about, and more often than not, they’re recordings by the New York Philharmonic and Leonard Bernstein from the 1960s. But rarely do I go into Bernstein himself, the seminal composer, conductor, pianist, lecturer, etc. (this is a BIG et cetera, not a LAZY one — he really did do just about everything), who died a mere six months before I was born.

But who was Bernstein, really? Beyond the “Lenny” that seemingly every account of him refers to him as. Bernstein was born to a middle-class family in Massachusetts in August of 1918 (another Virgo!). He went to Harvard for his undergraduate (where he first met one of his significant mentors and friends, Aaron Copland), then the Curtis Institute of Music in Philadelphia. From there he worked in Boston for a time before going to New York City, where he took on the role of assistant conductor to the New York Philharmonic, eventually conducting the orchestra well before he turned 30. 30 under 30, baby!!!!

From there, Bernstein had almost too illustrious a career to go widely in-depth in this space. He was a figure of public admiration, always straddling the line between full-on genius and relatable guy next door. His Young People’s Concerts are on Youtube and very pleasant to watch, even if you do not identify as a young person. Also here is another good video:

And so: I’ve had Bernstein bouncing around my consciousness for the past couple of weeks, partially because he was (sort of) the subject of this very silly story and partially because last week I went to go see West Side Story for the first time (! leave me alone) on the big screen at a 70mm festival in Chicago.

Young Socialites Conjure the Ghost of Leonard Bernstein at the Dakota

I first learned about Bernstein through this making-of documentary that used to air on PBS, which I was also eventually required to watch in my high-school composition class. Bernstein in his later years was a simultaneously fascinating and terrifying character to me as a kid. Bernstein is harsh but not unkind, stern and direct. He knows what he’s looking for in every single song and he’s out to get it. This clip of him working with José Carreras is telling. This is, for a few reasons, considered the “official” recording of the musical. It’s more operatic and complex. It’s also the only official version that Bernstein himself conducted.

Have you listened to West Side Story lately? I would wager: no. It’s okay if you haven’t! I know there’s a new Calvin Harris album out seemingly every single week of the summer. But that goes for me as well. It enters and exits my subconscious every other year or so. I was lucky enough to play from it in high school, but rather than serve as a member of a pit orchestra, I played Bernstein’s adaptation of the score in his symphonic dances. Remember symphonic dances? Composite pieces, mostly upbeat, following a theme or sharing a narrative? They rule.

Listening to the Symphonic Dances From West Side Story (original from 1961) is also a good opportunity to appreciate what Bernstein was doing with the score. I know, I know, we love the Sondheim lyrics. They’re great! But there’s a magic to this score. I barely have words to even describe it. It’s light and — I’m trying not to exaggerate but — transcendent. There’s both a symphonic majesty to it, as well as managing to take everything we like about jazz except jazz itself. (Just kidding!! I like jazz. Leave me alone.) I’m partial to the deep musicality of the Cool, Fugue (what a title!).

Obviously the “Cool” sequence in the movie is legendary, but because it is so — sorry — cool (we all know that they’d cast a Hemsworth as this guy in 2017, right?), it’s easy to lose the musical balancing act of it. The vibes! The piano! The fricking BRASS! The symphonic dances are essentially one big brag: look at how good my music is that I stripped it down to make it more obvious. But it works, also! Bernstein was always all about this mix of high and low art. Making something deeply complex and occasionally strange that also felt accessible to any old idiot who liked good songs (me).

In the event that you can’t make it to a beautiful 70mm screening of West Side Story or music that has lyrics distracts you too much at work, take some time to revisit Bernstein’s work in the Symphonic Dances just to soak in all of Lenny-ness. Plus I’m pretty sure it’s easier than trying to hold a seance.

Fran Hoepfner is a writer from Chicago. You can find a corresponding playlist for all of the pieces discussed in this column here.

A Poem by Chaya Bhuvaneswar

Mount of the Dead Men

Sculptor left your stone eyes blank. But you were busy looking someplace else.

No dancing girl, Mohenjo Daro, terra cotta, Indian Jazz Baby, Twenties flapper contraband for bobbed hair alone.

You’re one of us, all the real girls.

Three steps you were supposed to stay behind but you two-stepped, grape-vined, twined closer with a lover’s hand. Moved him out of the way, so you could see words he was reading.

Half out of his mind with grief once you were gone, out of sight, out of mind, he listened to you then, instead of expecting you to look at him.

In fact, it was his eyes that went blank then, listening for words you had to say that were his words, not finding them,

not finding you. No Eurydice, no Beatrice, no Muse, no Magic Bus.

You only came up to here, on him, but had it up to here with him.

And had your way. And didn’t get your way.

As one of us, all the real girls. An Amrita, Arundhati, Mira, Deepa, Mahesweta Devi.

You were a gritty brown bottom exhibiting yourself, telling stories of what the sculptor did. Leaving your eyes that way, so you couldn’t see.

Chaya Bhuvaneswar’s work has appeared or is forthcoming in Narrative Magazine, Michigan Quarterly Review, Nimrod, Asian American Literary Review, Notre Dame Review, aaduna, r.k.v.r.y., Redux, Bangalore Review, and elsewhere.

The Poetry Section is edited by Mark Bibbins.

Cornelius, "In A Dream"

It’s like the middle of July out there.

It’s hot. Here’s another one from the new Cornelius record, Mellow Waves. Enjoy.