Seeking Solace in SCUM

by Haley Mlotek

At the moment, I don’t feel like praising a manifesto that calls for the extermination of a particular gender. This is my own fault. If I had just filed this essay when I was supposed to, I could have avoided this stupid fucking problem.

But watching my news feeds fill themselves up this last week, I felt like I was being force fed. I could have turned it off. But that felt like the ultimate luxury, to close my eyes and pretend like it wasn’t happening. I haven’t watched his videos, or read his manifesto, but his presence has had a drastic impact. I’ve never followed the Didion cliché of writing to find out what I feel: I’ve always had a feeling first; the challenge was to find the right words to describe it. This is the first time I have words and research and context but am unable to identify even one concrete feeling.

What are we to do when someone shows us, in ink, exactly who they are and who they hope to become?

I’ll never know if I knew about the SCUM Manifesto before or after I knew about Andy Warhol. It’s hard to differentiate when one person takes up so much cultural space; the other objects around seem to get farther away, like traditional three-point perspective. But Valerie Solanas’s writing continues to pull me to her. Mary Harron said that the SCUM Manifesto “feels as if it were written in one great rush. It isn’t quite like anything else, but it does resemble Artaud’s surrealist manifesto… Also de Sade in its vision of human nature… And, more disturbingly, it resembles the better bits of writing by the Unabomber.” When I want to think of Valerie as being separate from Warhol, am I doing her a disservice, imagining her to be wholly satirical when the manifesto had at least some glimmer of truth? When reporters asked for a comment at the police station she was booked at, Valerie told them to read her manifesto for answers.

Breanne Fahs’s brilliant Valerie Solanas: The Defiant Life of the Woman Who Wrote Scum (and Shot Andy Warhol) is clear at least that satire was a long tradition in Solanas’s writing, and that she used humor and hyperbole to make her points. She wanted to kill Warhol because of a perceived slight — made so, so much worse by her undiagnosed and untreated paranoid schizophrenia.

But I am so, so torn on how to explain why Valerie Solanas wrote one of the most important feminist works we’ve ever seen, why the SCUM Manifesto deserves your attention this month, of all months, or any month. The SCUM Manifesto is, obviously, in entirely its own class — “SCUM will kill all men,” she writes, just after declaring free subway and bus tokens for all — and I don’t really think it’s fair to compare it to the Unabomber, or to our most recent domestic terrorist. It’s more that I feel compelled to acknowledge the place they hold in our cultural space, perhaps all equally in focus. Another paraphrased Didion cliché (my last, I promise): Do we read these manifestos not in order to live, but because we lived? Because they show us, at least, a record of the attempt to articulate what the writer felt?

Valerie Solanas — author, playwright, scientist, philosopher, visionary, sex worker, friend, sister, daughter, splinterer-of-feminist-movements, and, fine, almost-assassin of contemporary art’s most beloved male artist — was big on dedications. She dedicated her play, “Up Your Ass,” to herself, writing:

I dedicate this play to Me; a continuous source of strength and guidance, and without whose unflinching loyalty, devotion and faith, this play could never have been written. Additional acknowledgements: Myself — For proofreading, editorial comment, helpful hints, criticism and suggestions and an exquisite job of typing. I — for Independent research into men, married women and other degenerates….

This week will mark forty-six years since Valerie’s assassination attempt of both Warhol and her publisher, Maurice Girodias — the shots heard ‘round ironic representations of pop culture then and forever. Valerie is married to Warhol now, never mind until death did them part. Breanne Fahs’s incredible book does not try to minimize that connection; it only asks us to think of the event as a moment in Valerie’s life, connected to everything before and everything since, rather than the moment.

Towards the end of Valerie’s life, she spoke often about the million-dollar advance she believed she would receive for her authorized memoir, Valerie Solanas, which she was convinced would sell twenty million copies. “Valerie hated the idea of imperfection, of others representing her life and work, of errors to the official record of how things went down,” Fahs wrote in her preface. “The irony of now writing a book called Valerie Solanas that gives an ‘unauthorized’ account of her life, offering up a text filled with the potential for error (and, of course, Valerie’s posthumous cosmic revenge) is not lost on me.”

In one of those moments, Valerie was a features reporter for her university newspaper. She wrote satirical pieces about the oppressive nature of the patriarchy she saw on campus. Men complained. One of them wrote a letter to the editor that said, “It would appear that Miss Solanas establishes a point only so that she can stab something or someone with it.” The precedent was set. Solanas’ writing would always be read as half joking, half serious, and fully dangerous. In another moment of hilarity, Arthur Miller once complained to hotel management after Valerie left posters advertising auditions for “Up Your Ass” in the Chelsea Hotel lobby.

Mary Harron’s extensive research for her film I Shot Andy Warhol provided a pathway for Fahs’s biography, because so much of Valerie’s life was unaccounted for; she moved frequently, unable to make rent, and her letters home seem deliberately vague on her whereabouts. Through interviews with Harron, as well as Ti-Grace Atkinson, Jeremiah Newton, Ben Morea, Ultra Violent, and family like Judith Martinez (Valerie’s sister) and David Blackwell (Valerie’s son, given up for adoption at birth), amongst others, we get a real sense of who Valerie was to the people who lived and worked with her, the people who loved and feared her — and what transpired on the day of Warhol’s shooting.

Valerie went Lee Strasberg’s studio, hoping that he would want to produce her play. Strasberg wasn’t there, but his student Sylvia Miles was, waiting to start preparing for her role in Midnight Cowboy. Miles had a bad feeling, and made Solanas leave.

But then — and this is the part I can’t stop thinking about — Fahs details how Solanas went to Margo Feiden, a child prodigy who had produced “Peter Pan” on Broadway when she was only sixteen years old. Feiden let her into her apartment and allowed Valerie to talk about why Feiden should produce her play and join the SCUM Movement. Margo remembers her being quick and intelligent, with an answer prepared for every question.

When Margo refused to produce the play, Valerie took out her gun and told her she was going to shoot Andy Warhol, become famous, and then Margo would have to produce her play. Margo refused, tried to reason with her, but Valerie left.

Here’s the part I can’t believe: Margo, obviously, called the police to tell them what had happened. She called her police precinct, the police precinct in Andy’s neighborhood, and even the offices of New York’s mayor and governor to warn of a serious threat on Warhol’s life. Everyone told her to stop wasting their time, even asking how she could possibly know what a real gun looks like. (Similarly, the New York Times dismissed her account as well.) “As I was frantically making these phone calls,” Margo told Fahs, “I left the television on, knowing that if Andy were shot, regular programming would be interrupted with breaking news.”

When the news finally did come on the screen, she broke down, guilt-ridden over her inability to stop Valerie. “And I’m still not over it,” she said. The questions the police asked were not entirely about whether or not she knew what a gun was. The question seemed to be, how could one woman know what another woman was capable of?

Something strange happened the other day: I left my house. That’s not the strange part, although I don’t do it so often anymore. I work from home, and also lately I hate everyone and everything, so I tend to stay inside as much as possible.

I’ve only recently started to feel isolated. Since the sun came out I’ve begun to feel claustrophobic. I’ve needed to remind myself why, exactly, the ability to stay home for days and days without ever leaving is a good thing for my career, my life, my sanity. For the first time in years I’ve begun to crave the outside world, to sit in the park and do nothing, to just be outside and warm.

So I did leave my house the other day, and as I stepped outside and felt so happy to step into pure sunshine and real warmth, I immediately noticed the black car with the windows rolled down blasting some sort of talk radio, a man in sunglasses in the front seat, not looking forward or to any one side exactly, sort of looking up.

I turned the corner and didn’t think anything of it, but the sound, the hateful chatter of talk radio, followed me. I got a block away before I realized it wasn’t that loud at all, it was just close. The car was creeping along my street with me but I was too ashamed to be scared, unsure if I was paranoid or narcissistic, assuming the worst without hard evidence. I wanted to look at the license plate but I didn’t want to look to my side or straight ahead so I just kept, in my sunglasses, sort of looking up.

I ducked into the park where the car couldn’t follow me. The car began driving at the regular speed limit, sped away, the chatter disappearing with it.

That night, around ten, I met some friends for drinks — alone — at a bar not too far from my house. A male friend asked if I had walked from my house. I told him no, guiltily; I was ashamed to have been so lazy, but I took the bus, a three dollar indulgence to my paranoia. He was glad to hear it. Everyone was talking about the three women who had gone missing in my neighborhood (since located, thank God), not to mention the other woman who had been abducted not too far from my home and escaped after being held for 28 hours. He asked me to please not walk at night, to stay with my boyfriend or on buses or in cabs, to indulge that paranoia because it just wasn’t safe. I thanked him, sincerely, touched. His concern was so infuriatingly gratifying — like, yes, a man also thinks I should pay my way out of being afraid to walk down my street! I must be doing something right! And then my boyfriend met us at the bar and after midnight we walked home, slowly, enjoying the summer night the way I’d been dreaming of all winter.

It’s boring to hear about other people’s dreams, I know, but please hear me out. A few months ago I began reading books by Virginie Despentes, finishing Baise-Moi in a single night, and I dreamt I murdered a woman I didn’t know with a knife and her blood, red in my peripheral vision, turned orange when I looked directly at it. Last week, I read Jane: A Murder for the first time and dreamt of seeing a magic hour from inside my apartment, watching the sky go from pink to navy, while I knew a woman was screaming, though I didn’t actually hear it, I just knew it was happening. A few days ago I read An Untamed State and dreamt of a beach where I was totally alone but for once didn’t want to be. Isolated and claustrophobic in all that open space.

I read Twitter, too, even though I shouldn’t have, and then dreamt of sitting at my computer with my fingers resting on the keyboard, not typing, not moving, seeing a scroll of information go on and on and on. I saw that photo of the man in Santa Barbara everywhere, the selfie taken in his car at magic hour, and felt isolated and claustrophobic, alone in my infinite space.

This month has been hard, I say to my female friends, but all our months are hard. There’s nothing to distinguish that hard uphill feeling from one month to the next. Sometimes its aggravated by major events like the Isla Vista killings, by police statements that say the disappearances are not connected, by signal boosts and trigger warnings and male friends who are concerned with your safety because, of course, they are not like those men.

I don’t dream of the one man who I would, honestly, like to commit an act of violence against — the only person on earth whom I think I would kill with my bare hands, or would take a knife or a gun if the opportunity arose. But I have waking dreams. Sometimes I’ll be walking down the street or brushing my hair and I imagine some elaborate dream scenario. We bump into each other, see each other at some public space, and I’m not scared, or sad, or panicked, but I am calm and cool in a way that makes men cower at women’s feet. I know I am at a disadvantage: My panic would make me weak in the knees; I remember the strength of his hands, believing that their force on my shoulders and ribs would bruise me (it didn’t, no marks). He could fit one hand around my neck and still make his fingers touch, I know. But in my waking dreams he is terrified of what my hands can do.

I know what is wrong with Valerie Solanas. I know, too, what’s wrong with films like Spring Breakers, or the writings and films of women like Virginie Despentes, that transferring the perpetration of violence to a different gender is subversive only in theory, that all violence is wrong. I know a manifesto that leads to murder is an open and shut case. But; but. I am haunted and soothed, betrayed yet comforted, by the imaginations of women whose hands could be instruments of destruction.

When women write, or threaten, or commit, acts of violence, they are anomalies; Margo Feiden couldn’t even get a police officer to take a real statement, let alone protect Andy Warhol, because it was a woman on the wrong end of the gun. Even when women are quite obviously the targeted victims of an attack, still we read and write and tweet about how they were barely targets, how their gender was an almost nonexistent part of the threat or act.

The night I re-read SCUM Manifesto I slept peacefully. No dreams. Even with the dreams, I loved reading all those books, loved discovering what those authors created for me. I know what men are capable of; I know what women are capable of. I know what kind of violence and cruelty men and women can write. Still I read. Valerie was asked by reporters what her motive was. “I have a lot of very involved reasons,” she said. What’s mine for continuing to read, knowing what I know? I have a lot of very involved reasons.

Haley Mlotek has a lot of opinions. She is the publisher of WORN Fashion Journal.

The Long Tail of Deadly Intersections

Here’s the surprising thing about the most dangerous intersections in New York City, like the Myrtle-Wyckoff-Palmetto death trap in Ridgewood:

“There are about 1,800 severe pedestrian injuries a year and you’ll rarely find an intersection with more than three or four in an individual year,” [Ryan Russo, DOT’s assistant commissioner for traffic management] said. Russo says that if you could eliminate every death and serious injury at the 52 most dangerous intersections, you’d reduce the citywide total by only four percent.

In other words, a graph of dangerous intersections would be all tail and no head; death lurks around every corner.

Profession Advanced

“Ryan Chamberlain, the social media manager who was wanted after explosive materials were found in his San Francisco apartment, has been captured after a three-day manhunt.”

Human vs. Citi Bike: New York's Secret Struggle

by Leon Neyfakh

Some of these people get lucky, parking their bikes within seconds and heading happily toward home. Others — those who stayed late at work, perhaps, and thus arrived on the wrong side of the evening rush — encounter devastating disappointment, as they realize that the one or two open slots on the rack are only open because they’re hopelessly broken.

Most people who find themselves in this situation spend some time trying really hard to make the slots work. They shove their bikes into them as forcefully as they can, hoping with every thrust that the mechanism will lock like it’s supposed to. But in the end, everybody gives up and rides sadly away.

I guess I could have written a helpful sign or something, to save these poor stranded people from their abject frustration. Instead, I spent a month filming them from my window, watching silently as they banged their bikes against the unwelcoming clasps; their heads against the brick wall of life. The resulting video, edited by New York Magazine videographer Abraham Riesman, is a document of crushing defeat and a glimpse into the general futility of existence. Enjoy!

Leon Neyfakh tweets here.

How a Meme Becomes Myth

What could drive two 12-year-old girls to allegedly stab a friend in a methodical, premeditated fashion? If you take their word for it: Slender Man, a character conceived on an internet forum in 2009 and subsequently featured in countless amateur stories and a series of low-budget games. Here is the local paper’s account:

Both suspects explained the stabbing to police referencing their dedication to Slender Man, the character they discovered on a website called Creepypasta Wiki, which is devoted to horror stories.

Weier told police that Slender Man is the “leader” of Creepypasta, and in the hierarchy of that world, one must kill to show dedication.

Contrast that with the origin story of the character:

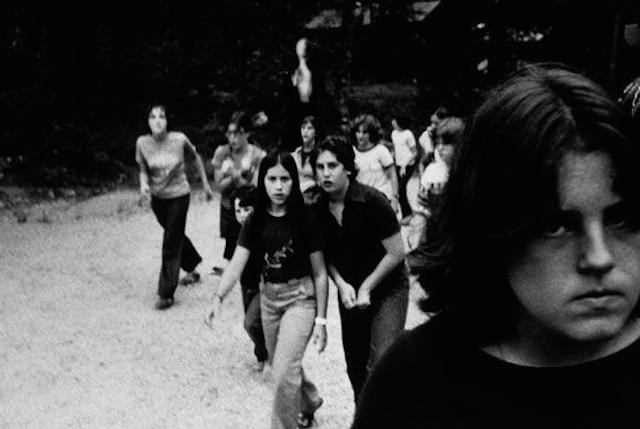

On June 8th, 2009, a “’paranormal pictures” photoshop contest was launched on the Something Awful (SA) Forums. The contest required participants to turn ordinary photographs into creepy-looking images through digital manipulation and then pass them on as authentic photographs on a number of paranormal forums. Something Awful users soon began sharing their faux-paranormal creations with layered images of ghosts and other anomalies, usually accompanied by a fabricated witness account to make them more convincing. On June 10th, SA user Victor Surge (real name Eric Knudsen) posted two black and white photographs of unnamed children with a short description of “Slender Man” as a mysterious creature who stalked children.

If you’re 12, 2009 may as well be a century ago, and the Creepypasta Wiki may as well be a sacred text. It is impossible to get inside the heads of these children, or, for now, to understand what else may have motivated them. Maybe these stories were the catalyst! Or maybe they were just available in the periphery of broadly disturbed lives.

It is easier, however, to get in the heads of reporters, who are using language like this.

That’s from the Washington Post, which goes on to refer to Slender Man, an internet meme, as “a mythological demon-like creature” and “the demon.” The Daily Mail calls Slender Man a “prevalent internet myth.”

I suppose that’s a more compelling way to provide context than describing Slender Man as “a recent phenomenon in the ad-hoc creative writing communities on sites like 4chan, Reddit and Something Awful,” or something, but it also gives far too much credit to what amounts to a forum myth that started as a prank. Which might be fine, if the accused weren’t getting so much credit themselves: They will be tried as adults.

Alexander Shulgin, 1925-2014

“Alexander ‘Sasha’ Shulgin, the pioneering pharmacologist who introduced MDMA to psychologists in the 1970s, has died.” He was 88.

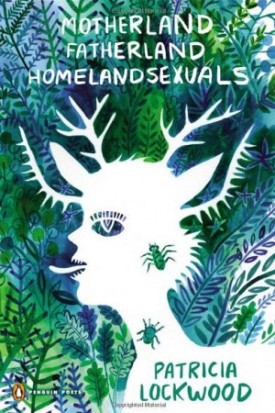

Men Unsettled by Woman's Poems

Patricia Lockwood’s new book of poetry, Motherland Fatherland Homelandsexuals, came out last week. There have been a handful of reviews in mainstream outlets, like in the New York Times, where Dwight Garner calls it “a satirical work that nonetheless brings your heart up under your ears.” His criticism, such as it is, notes, “When her poems miss, which they frequently do, their ideas seem larval and merely cute.” It concludes, “little hairs on my back rose often while reading ‘Motherland Fatherland Homelandsexuals,’ as if it were the year of the big wind. That’s biological praise, the most fundamental kind, impossible to fake.”

But then are there some other reviews, and there is a mildly curious pattern to them. Here’s the first paragraph of Jonathan Farmer’s, in Slate:

Here’s the thing: For the most part, I don’t like reading Patricia Lockwood’s poems. They make me feel slow-witted and over-serious, clumsy, credulous, and uncool. They make me feel like the guy who ruins all the fun. Her poems aren’t wrong; I am that guy. But I don’t like being reminded.

And here’s Adam Plunkett at The New Yorker online:

Even the zany comic sexuality, unsettling as it can be, is never more nuanced than the brutish, broish caricature she tweets about and that tweets back at her. In “The Hornet Mascot Falls in Love,” for instance, the hornet is sexual aggression incarnate: “Oh he want to sting her…. The air he breathes is filled/with flying cheerleader parts.” It’s easier to laugh at what he represents — “astonishing abs,” sports, machismo — than to feel his sexual frustration and anger. “Revealing Nature Photographs,” a poem transposing onto nature the ways we objectify women, ends with a repulsive invitation: “Nature turned you down in high school. / Now you can come in her eye.” This is addressed to a man but written for people to laugh at him, even if the poem doesn’t evoke Nature well enough to think of her as any sort of woman, let alone one whom you repressed your anger toward. But the subtleties of men’s desires were never the point.

Lockwood’s poems are sexually explicit, ridiculous, and unconcerned with the desires of men, and thus two men seem to be made uncomfortable, one shamed by his own discomfort, the other, not so much. (Worth noting: it seems that almost every review of the book — whose most famous piece is a poem about rape — so far in a major outlet has been written by a man?) The conclusions to be drawn seem dourly straightforward. This is strange. Why do these particular poems, by this particular person, in this particular book, at this particular time, bother these particular men?

Surreal, sexually explicit poetry is not new, not even by women (lol), and it seems unlikely that these men would feel similarly discomfited by weird sex-tinged poems written by another man. Men talk about cocks in bizarre ways all the time, after all, in every medium imaginable. The first cave painting by a dude was probably of a funny-looking cock.

Let's Choose Our Next Metric Very, Very Carefully

Flipboard, my god. How about a temporary moratorium on new audience measurement standards, just for a few months, to give everyone some time to catch their breath and, I don’t know, reconsider a few things? The concept of “page flips” is perfectly meaningless and self-contained, and Flipboard is struggling, so who really cares. But meanwhile, over at Medium: “[S]ome people are now paid not by clicks, but by the total time spent reading in their collection — another experiment that could change as we learn what effects it has on the types of stories it helps produce, and how people find and read them.”

What if that catches on? It sounds sort of appealing at first — it’s certainly more honest and direct than some of the old metrics — but it also puts readers in a direct battle with publications for time, which is literally the most important thing in the world. It’s interesting to imagine what happens when a publisher’s goal is not to attract clicks or eyeballs or shares, but to seize time by whatever means possible, to maximize the number of seconds it takes to absorb content, whether or not that goal aligns with the ostensible purpose of what’s being published (a diversion should waste time; a breaking news story should spare it). Maybe it’s the best option we have! Or maybe it’s how the internet turns in TV.

New York City, June 1, 2014

★★★★★ The morning was not, factually speaking, bright enough to overcome sleep, though it ought to have been. Outside was mild everywhere, save only the toxic microclimate of a street fair, sun-baked and smoke-smothered. The nonfestive used-items vendors sat in their usual sidewalk spaces, now behind the backs of the booths, in individual envelopes of sound: Joan Jett, reggae. The two-year-old was in a dangerous frenzy in the grocery aisles. Taken to the plaza outside the apartment to burn it off, he sent a toy car pinwheeling over the bricks again and again, with some indistinguishable combination of enthusiasm and malice. At naptime, music — a PA system — carried over from who knows where and up 27 stories. Out on the street again, more music blasted from a passing car. Men at the street fair were taking the opportunity to walk around bare-chested, with their shirts in their hands. The playground was dappled and just short of delirium. A preschool classmate grabbed the two-year-old and went one way; a fellow first-grader grabbed the six-year-old and went the other way. The younger boys made a foray to the shady threshold of the women’s restroom, then decided to go play on the slides. The older ones settled into a sort of lopsided kickball game with a tennis ball. A heavy ball slammed into the far side of the chain link head-high; a sparrow came diving by at shoulder level; a little remote-controlled helicopter shot by at groin altitude, with a harsh insectoid chatter, and crashed into the near side of the fence. The tennis-kickball went rolling the wrong way and, with the shocking precision of dumb fate, intercepted the front end of a distant and perpendicularly moving scooter, stopping it dead, pitching the rider over the handlebars. The two-year-old got ahold of the ball and threw it away down the ramp to the school, where it went through a fence and out of reach. Back home, the sun reached into the kitchen to play on the steam coming off the saute pan while a batch of browned cauliflower finished up, after a long day in the slow cooker.