Mutual Benefit, "Auburn Epitaphs"

Jordan Lee has reissued his 2011 EP,Cowboy’s Prayer, which I missed and I imagine plenty of other people did too, because everyone misses everything. It’s not clear anymore where we’re supposed to be looking in the first place! Anyway, here is a song that sounds like a nice big room and feels like a handful of ibuprofen.

Where Fancy Garbage Coffee Has Never Gone Before

All coffee is good, from the shittiest diner to the most annoyingly rigorous high-end shop, except for coffee that comes in a pod and claims to be annoyingly rigorous and high end, but which is actual garbage that has been toasted, ground up, dehydrated and put into a non-biodegradable plastic coffin. And now that coffee is in space, which is a good reason to never leave this big dumb rock with all of its perfectly fine non-garbage coffee.

The Problem of Coolness, Solved

“Despite assertions that coolness sells products, little is known about what leads consumers to perceive brands as cool.” ~ Caleb Warren and Margaret C. Campbell, “What Makes Things Cool? How Autonomy Influences Perceived Coolness,” forthcoming in the Journal of Consumer Research.

A brief summary and analysis of the study’s findings:

Although researchers do not agree on a specific definition of coolness (Dar-Nimrod et al. 2012; Kerner and Pressman 2007), a canvas of the literature reveals agreement on four defining properties. One, coolness is socially constructed. Cool is not an inherent feature of an object or person but is a perception or an attribution bestowed by an audience (Belk, Tian, and Paavola 2010; Connor 1995; Gurrieri 2009; Leland 2004). In this sense, coolness is similar to socially constructed traits, like popularity or status (Hollander 1958); objects and people are cool only to the extent that others consider them cool.

Cool.

Two, coolness is subjective and dynamic. The things that consumers consider cool change both over time and across consumers (Danesi 1994; MacAdams 2001; O’Donnell and Wardlow 2000). Despite the subjective nature of coolness, consumers have little difficulty recognizing coolness when they see it (Belk et al. 2010; Leland 2004)

Wow, that’s cool!

Three, coolness is perceived to be a positive quality (Bird and Tapp 2008; Heath and Potter 2004; Pountain and Robins 2000). The few quantitative empirical studies on the topic confirm that cool people tend to possess personality traits considered desirable by the audience evaluating coolness (Dar-Nimrod et al. 2012; Rodkin et al. 2006).

Nice.

Four, although coolness is a positive trait, coolness requires more than the mere perception that something is positive or desirable (Leland 2004; MacAdams 2001). Pountain and Robins (2000, 32) write, “Cool is not merely another way of saying good. It comes with baggage.” Consumers perceive some quality that sets cool things apart from other things that they merely like or evaluate positively. However, the literature is not clear as to what this additional quality is.

Good good, cool: Good, and also cool. As for the purpose of the study, to establish what makes things cool?

Understanding what makes things cool has puzzled academics and marketers alike. We address this question by empirically examining the relationship between autonomy and perceived coolness, finding that brands and people that diverge from the norm in a way that seems appropriate are perceived to be cool.

Things that are cool are cool — but only if they’re cool. Nice, and cool.

Welcome to San Williamsisco

We could quibble, if you wanted, about when the sociocultural phenomenon known as “Williamsburg” “began” and when it “ended”; neighborhoods do have a tendency to “end” right around the time you can longer afford to live there, or perhaps a touch before then. (The average rent for a studio in Crown Heights today, by the way, is $1760, up from under $1500 a month ago, according to one firm. We still have Quooklyn, right?)

Let’s focus, instead, on this:

He noted a firm analysis finding that Williamsburg residents are now on average 25 to 35 years old with per capita income of $108,000 a year.

Whether the Williamsburg you know ended with Diner in 1998–1999 or Marlow & Sons in 2004 or the Wythe Hotel in 2012 (or whichever milestone you prefer!), the average human living in Williamsburg is now, officially, a rich person — and a young one, at that.

Photo by several seconds

The Miscellaneous Genius of Jason Derulo

For an album with at least five potential hit singles, Jason Derulo’s Talk Dirty is staggeringly weird. Its cartoonishly raunchy titular song, for example, is structured around a klezmer alto sax line sampled from a band called Balkan Beat Box. Two tracks later is the ultra-sweet pop anthem “Trumpets,” which sounds like a Glee cover of itself, and which also maintains the album’s forceful but basically unintelligible sense of sex:

Is it weird that your ass

Remind me of a Kanye West song?

…

Is it weird that I hear

Trumpets when you’re turning me on?

Turning me on

Is it weird that your bra

Remind me of a Katy Perry song?

“Bubblegum” is just a straightforward butt song. “Kama Sutra” is an algorithmic tribute to penetration and commitment. “Zipper” is a song-length simile about intercourse that goes up and down and up and down until it finishes. “The Other Side” is a Katie Perry song, more or less, and a good one. Can you guess what it is that Jason Derulo wants to do “With the Lights On?”

Then there is the profoundly horny “Wiggle”, which is millimeters short of a novelty song.

It begins with a catcall sketch and then spins off in about three different directions:

The entire album is assembled from odd parts, some truly alien and some just reclaimed from unlikely places, and it’s wonderful. This song, however, might be the most disparate: There’s Snoop Dogg playing a sort of elder creep role with his wiggle wiggle line; there’s the pat-a-cake Instagram nursery rhyme; there’s even a Schwing! for effect (the first Wayne’s World sketch on SNL aired six months before Derulo was born). The hook is played on a toy flute purchased from Party City. But the weirdest part of this song isn’t so easy to notice — it gets lost in context. Skip to 2:30, or just click here.

Is that??? Wait:

Yes! Derulo is singing to the cello part in the Game of Thrones theme song. Up an octave, shuffled around, but it’s there. It takes a couple listens — these videos might help:

Or this one is better, actually:

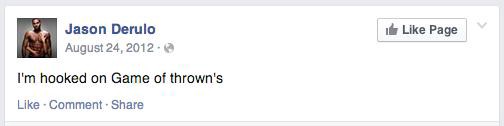

I mean, sure, same scale, similar sound, whatever. But I don’t think that’s all! In this interview, he identifies Troy as his favorite movie, before muttering something about being “obsessed” with GoT. Then there are these messages from two years ago:

Haha, Jason Derulo, what is your deal? And how did it somehow result in the best album of the year so far? If you’re watching the GoT finale this weekend, listen up. And know that Jason Derulo, American music’s most quietly eclectic pop star, is probably watching too.

New York City, June 12, 2014

★★ Another dark and warmthless waste of the year’s longest days. Intermittent rain again, mist again, damp sluggish air in the subway. Sidewalk tables were empty. Water beaded on the seats of the outmost aluminum chairs. A backhoe bucked and dropped clods of dirt into a dump truck. An insistent breeze carried news of industrial cooking, news of feces. In the afternoon, in the sculpture garden that poses as a public amenity, the wind made the silvery grass sway, till a rubber-booted volunteer asked the public to leave.

A Movement, Defined

And now, an enthralling oral history of one of the most important photos on the internet: the definitive Wikipedia image for “grinding (dance).”

So we all grabbed some props, because we are sheep, and the hat stayed with Joe all night. After a surprisingly small amount of convincing, they got on the bar and history was made. They were up there for at least 2 minutes, collecting dollar bills while losing a bit of dignity. Of course i had to take a pic, because it was my duty to embarrass them with it later.

This is how history is often made: two embarrassing minutes at a time.

The Original "Say My Name"

by Casey N. Cep

Joe Allison had trouble hearing his wife, Audrey, on the phone. “Put your sweet lips a little closer to the phone,” he’d say. One day, she wrote it down so they could turn it into a song. A singer called Jim Reeves recorded that song, “He’ll Have To Go” in October of 1959; it topped the charts by February of 1960.

“Put your sweet lips a little closer to the phone,” Reeves says, only he’s not a husband who can’t hear his wife, but someone whose someone is with someone else: “I’ll tell the man to turn the jukebox way down low,” he sings, “And you can tell your friend there with you he’ll have to go.”

It’s a ballad that sounds a little like a waltz, the piano and vibraphone twinkling throughout. “Whisper to me, tell me do you love me true,” Reeves asks and then demandingly: “Should I hang up or will you tell him he’ll have to go?”

Hard to believe anyone could say no to that baritone voice, or that that it would take any more convincing, but Reeves pleads: “You can’t say the words I want to hear while you’re with another man. Do you want me? Answer yes or no, darling, I’ll understanding.”

It was the original “Say My Name,” although Reeves doesn’t just suspect he’s pleading with a cheater, he knows there’s another man, and not just in the world, but in the room. There’s a difference, too, between when Destiny’s Child made their case in 1999 and when Reeves made his forty years before: in 1959, not everyone had a telephone, especially not in rural areas. Your neighbor might have one, or maybe you could walk to a pay phone, but part of the drama of “He’ll Have To Go” is it’s happening over telephone wires.

One of the first country songs to talk about the telephone was released by the Carter Family in 1929. “No Telephone in Heaven” is about a girl who asks a store clerk if she can call her mother in heaven, but two of the most popular phone songs in my country lifetime are Travis Tritt’s sassy “Here’s a Quarter (Call Someone Who Cares),” and Blake Shelton’s “Austin.” One’s a breakup and pay phone, the other a makeup and an answering machine.

But those all came later. In 1959, it was Jim Reeves pouring his heart out in some bar or restaurant, asking the proprietor to turn down the jukebox so he could hear his someone on the line. There were plenty of ways to break a partner’s heart in print, but hearing someone’s voice as they lied or refused to deny was still a relatively new experience.

“He’ll Have To Go” is a direct confrontation with infidelity, and while we have so many more ways of taking or faking calls, we’ve actually gone back to something like the days of telegrams and letters. Think of seeing some cheater’s tweet geotagged from your town, or realizing that your partner’s phone recognizes somebody else’s Wi-Fi network. You notice a familiar wallpaper pattern in the background of a Snapchat or see the same Foursquare checkin. Any one of those and you might well email or text to say “He’ll Have To Go,” just as someone in 1959 would’ve called, instead of saying so in person.

When phones invaded every house and every hotel room, Reeves’s song faded into familiarity, but now that they’re in every pocket and purse, it’s once again unfamiliar and strange. The sadness of “He’ll Have To Go” isn’t so much in realizing your someone is cheating, but having it confirmed by her sweet voice. Asking someone to put her sweet thumbs a little closer to the phone just isn’t quite the same.

Casey N. Cep is a writer from the Eastern Shore of Maryland.

A Poem by Alexander Chee

by Mark Bibbins, Editor

I DON’T EVEN

I don’t even know what to tell you

about the fog

or anything else for that matter

what did you think was coming

what did you think mattered what did you think

there was something we were all going to do right

something we made in pieces in the dark

we kept it secret we said it would be better that way

we didn’t even look

we forgot the way that was better

we forgot all the other ways too even all the shitty ones

but the pieces are there

what would it take for you to really give up on someone

I wrote this in my journal about 7 years ago

I give up on the journal more than I give up on other people

every few months I write an entry and I say ok every

day now an entry and

the journal is all like this guy again really

really the journal is always there for me though it is like me

but I suppose as these other people experience me

this one or that one I won’t give up on and who doesn’t know

how I wait the journal is not a record then but a mirror

a trap a friend a place it all goes if I can only get there

and maybe that is what this person thinks of me but

that would mean I am the mirror too

that of course would be awful

why even keep the journal you ask why does it matter

it matters because it is where you figure yourself out

why abandon the journal

because you can’t figure yourself out or you can’t

bear to figure yourself out or you can’t bear

to watch yourself figure yourself out

you are like the beat cop watching the robber

who always comes to that one house and he never quite gets in

the cop can’t bear to arrest him it all just seems too stupid

look he fell down again he’ll never rob that house

and of course you are also the robber and you are the house

why can’t you bear to figure yourself out

well that is really a good question

it would mean you are the pieces in the dark

you are the whole thing taken apart

and hidden so as to be safe and secret

you are the secret and the ways lost to the makers

and to figure yourself out would mean all the lights would come on

and you would know the thing you didn’t want to know

and the secret would be in danger again and all that could be made

could be made would be made

you are a message to yourself can you write this down sure

you are a message you left to yourself at some other time you will

remember if you could sit here long enough

you are a code and the thing hidden in the code and the code breaker

breaker breaker break break codebreaker break codebreaker break

break codebreaker break

just like that like some machine just like that

what is the secret is it is a loyalty to others

that never breaks machine of loyalty

no one believes in it they test it all the time all fools

what would it take for you to really give up on someone well

the someone would have to be you

Alexander Chee’s newest novel, The Queen of the Night, is forthcoming next year from Houghton Mifflin Harcourt.

The Drones Take New York

The Drones Take New York

by Aaron Reiss

On a frigid Saturday in March, two dozen members of The New York City Drone User Group (or NYCDUG, a local Meetup dedicated to amateur drone builders and pilots) convened at Van Cortlandt Park in the upper reaches of the Bronx. The group gets together every month or two to fly, build, and talk shop about unmanned aircraft. The group is a place where enthusiasts are trying to “find out what our position is in this crazy drone world — to find our footing and figure out how we can fit in the larger scheme of things,” said Fred Masson, one of its active members.

Drone pilots across the globe have have banded together in similar hobby groups; I counted over fifty Meetup Groups in places as diverse as Mexico City, Dayton, Ohio and Fairbanks, Alaska. Here in New York, the club counts over six hundred members. Riley Morgan is one of the youngest. At fourteen, he is regarded by many in the club as one of its most talented pilots.

Riley typically flies FPV (first person view) meaning he flies using goggles that project a live feed from a camera attached to his drone. He sees what his drone sees.

Riley’s father, Dan Morgan, does not fly drones, but acts as Riley’s spotter. He watches the drone’s position relative to the other drones in the sky and to other obstacles in the park, often giving orders in a slightly bored, fatherly tone: “Not so high, Riley… Keep your speed down.” Flying FPV has the effect of isolating the pilot. Riley sat away from the group, lost in the images feeding back from his drone.

In the US, drones exist in a legal gray area. Consumer-drone-specific regulations have yet to be established, and many of the pilots feel they are living through a sort of frontier period. This could change rapidly. In the last two months, conversations about future legal restrictions on drones have been thrust into the spotlight. In May, Yosemite National Park banned drones, claiming that they create “an environment that is not conducive to wilderness travel,” and “have negative impacts on wildlife nearby the area of use, especially sensitive nesting peregrine falcons on cliff walls.” The rules go beyond Yellowstone, effectively prohibiting drone flight in all 58 of the country’s national parks, according to CNN.

Even experienced drone pilots often find themselves in conflict with civilians, who are unfamiliar or uncomfortable with the machines. But drones can be truly dangerous in the hands of an inexperienced pilot. Pilot negligence made news in October of last year when David Zablidowsky (referred to in most media coverage as ‘inept drone user’ and a man who is certainly worthy of a good Google image search), sent his drone crashing into the side of a Manhattan skyscraper, and then plummeting down to the streets outside Grand Central Station. The Federal Aviation Administration levied a fine of $2,200, the first for a drone pilot who was not flying for hire.

Zablidowsky’s story elicits a special frustration with more experienced drone pilots, many of whom are worried that a few careless people could spoil the hobby for everyone. Debates among drone enthusiasts reflect a growing unease about he future of flying in public spaces. Following the FAA action against Zablidowsky, a member of the NYCDUG warned the other members of the group’s email list, “If we as […] aviators don’t find a way to police the type of flying that resulted in the [Zablidowsky crash] we might soon see FAA SWAT teams with automatic weapons at the ready assaulting kindergarteners flying balsa models in Central Park.”

Hobbyists hold that drones are a perfectly safe form of recreation, if used responsibly. Beyond recreation, pilots are quick to point out uses in the fields of journalism, advertising and more. Ed Barnes, a former war correspondent for LIFE and TIME Magazine (as well as for FOX News in Iraq, Afghanistan and North Africa) has seen drones used in war and is interested in “the huge impact they are capable of in civil society.”

An entry level drone could cost $400–600. The addition of GPS, a camera, and FPV can quickly turn hobbyist rigs into a flying, professional-grade cameras. Costs can quickly reach the thousands.

In Van Cortland park, a group watched with a mix of anxiety and amusement a small video screen showing a view from a drone which had just suffered a ‘fly away’ error. During the drone’s ascent, it lost contact with its controller, and simply continued with the last directive it was given — to ‘fly away’. The pilot (pictured in a black jacket) could only watch helplessly, fingering unresponsive controls, as $2,000 worth of equipment flew away and crash-landed in a dense forest on the outskirts of the park.

You can fly a drone using a hand-held controller, like you might use for an RC car. On the higher end, pilots invest in an entire suite of receivers, LCD screens, directional and omnidirectional antennae, GPS trackers and more.

Like many of the drone pilots in the Meetup group, Fred Masson (above) is trying to turn his passion into a career — he’s hoping to sell his services and footage to local filmmakers. The FAA, for its part, announced last week that it is considering granting its first commercial exemptions to seven aerial photo and video production companies.

The NYCDUG Van Cortlandt Park flying session ended when a park official politely asked the group to beat it, but Masson remained optimistic: “As these things get more advanced and people aren’t afraid of [drones] anymore, I don’t think anyone walking in the park will bat an eye.”