Future Foretold

Buried a little too deep in The New Yorker’s content mines for the site’s recent excavation, but available here, is John Seabrook’s legendary 1994 embed with MTV. From the office of the president of the network, Judy McGrath:

From the windows there is an amazing view of lower Manhattan, the Hudson River, and northeastern New Jersey, but the dominant view in McGrath’s office is of the television set, and when you go there for a meeting you have to remember to sit so that you, McGrath, and the TV are in the proper relationship to each other. At one of our early meetings, I made the mistake of choosing a seat across from McGrath at the round glass table that she uses as a desk, which gave me the best possible eye contact with her but put the TV behind me. What happened was that McGrath made eye contact with the TV, and I looked over her shoulder and out the window at two of the four faces of the huge clock atop the old Paramount Building, right across Forty-fourth Street, which stopped years ago (one face says 4:35, and the other says 5:50), and which McGrath says serves her as a convenient symbol of her peculiar state of arrested development. During the meeting, I found my body turning almost instinctively away from McGrath and toward the TV, until by the end of our conversation we were deployed in a triangle familiar to anyone who has sat around watching MTV with friends.

Who would have guessed that this odd and stressful physical negotiation, between bodies and screens, would be a constant feature of waking existence just a few years later? Probably plenty of people, in horror books about space. Anyway:

MTV is visual radio; it’s something you just have on. This is a fairly easy environment for kids who grew up in the seventies and eighties to adapt to, since the television was on pretty much all day while they were growing up, and the Bradys, the Fonz, and Mr. Kotter were like people they hung out with. But MTV ambience is surprisingly disorienting to people who grew up in the fifties and sixties, maybe because when Dick Van Dyke and Ed Sullivan were on the tube you sat down to watch them as though you were sitting in the audience.

I think about the “MTV ambience,” mute music videos playing on some screen in the periphery, and it sounds relaxing. Ruined!

A Night at the Ostrich Races

by Jared T. Miller

Past the array of simulcast screens with hypnotized leather-skinned regulars clutching bettor’s tickets like Blackjack hands, and beyond the families seated on long, wooden benches exchanging crumpled dollars for informal wagers, were the chariots. They were enameled and gleaming in candy apple red, cobalt blue and, pearl white. Beyond them were the tiny, darting heads of the ostriches that will pull them to glory.

The Cameltonian and Ostrich Derby is a Meadowlands Racetrack innovation, squeezed in between a few of the night’s regular horse races in the hopes of attracting spectators beyond the usual racetrack diehards. The camels and ostriches come from Hedrick’s Exotic Animal Farm in Nickerson, Kansas, a purveyor of dozens of game animals from Africa, Asia and other climates. It doubles as a bed and breakfast.

Camels made their way to the United States by way of traveling menageries in the early eighteenth century, but were first used in earnest in the Seminole Wars of Florida in the early nineteenth century. George H. Crosman, a career quartermaster and veteran of the Florida wars, so strongly praised their utility that he developed a U.S. Camel Corps to transport munitions and soldiers across the deserts of the American Southwest. Military use of camels effectively ended in 1861, however, after a Confederate attack on Camp Verde, Texas, where many of the camels were stationed. Confused with what to do with the animals — commanders used them to give Camel rides to local children — most were sent away for auction. They were bought by zoos and sold to other private owners, ending up as exotic entertainment as the advent of the transcontinental railroad alleviated the difficulty of long-distance cargo shipping. In 1992, modern camel racing became standardized, when the United Arab Emirates, a historically major exponent of camel racing, established the Camel Racing Association that dictated the rules and competitive practices for the sport across the peninsula.

The history of ostriches in the U.S. is of a more recent vintage: They first became a fixture in American livestock in response to demand for the birds’ feathers by fashionable women slightly before the turn of the twentieth century. The plumage was a status symbol, although not a new one, as Egypt’s Olympian equestrian racing Queen Arsinoe II (her tomb also contained a statue of her riding an ostrich) decorated her crown with them, a symbol copied extensively by successive rulers. Florida became one of the first states to host the animals, in the late eighteen eighties, with several farms producing feathers for decorations in women’s hats, as well as feather boas, stoles and fans. But before long, ostrich-feather demand cratered. In 1920, Popular Science reported on the phenomenon of tourists racing ostriches for fifty cents apiece at one Florida farm, boasting that the birds could “easily beat a horse in a long-distance race.” The sport never really caught on nationally, though it did become one of Florida’s earliest claims to fame.

Most of Hedrick’s ostrich and camel handlers grew up training and riding horses on nearby farms. The experience translates relatively well to exotic game, particularly the camels, which are well behaved and obedient, said Monty McClurg, a barrel-chested handler with a Teddy Roosevelt moustache. “Snickers is a very honest camel, very loving, very eager to please,” McClurg said, rubbing the camel’s jowls approvingly as he spoke. “If he was a human, I’d be proud to have him as a son.” The ostriches are a bit more challenging — with a brain the size of their eyeballs, they’re not particularly keen to follow commands. AJ Agusto, another handler from Hedrick’s, said that ostrich training is a bit like rote memorization: The key is running them in straight lines over and over until they stop forgetting what to do. “There’s training that goes into it,” Agusto said, “But it’s not where the bird has to think a whole lot.”

Down at the track’s opening stretch, a truck pulled up, filled with ostriches and their handlers. The tailgate dropped and three men, clad in Roman-style plumed helmets and color-coordinated capes, sprinted out to ready their chariots. As the birds were led to the track, they stomped their feet, sputtered, and resisted any attempt to mold them into a straight line. After the handlers successfully managed to swing the birds around to attach them to their vehicles, another handler, a few hundred feet away, yelled, “When the birds start comin’, hold the nets up real high!” White plastic industrial netting was unspooled and lined up along the track’s finish line.

Without fanfare from the announcer’s booth or much of a signal from the track, the birds snapped to attention and took their first frenzied strides; the starting gate truck driver floored it to escape the charging birds. The pack — consisting of Featherduster, Featherbrain, and Skeezix’s Big Bird, according to the day’s program — made a beeline for the netting stretched out in front of them, their riders crouched and coiled in anticipation of erratic ostrich behavior.

But the birds ran in an admirably straight line. The chariots kicked up small dust clouds behind them, picking up speed backed by a crescendo of cheers. As abruptly as the race began, it was over. Just as the avian racers began to hit their stride, and the crowd’s excitement peaked, the riders cut the ostriches loose in unison, their quick-release cables falling from the harnesses. The carts skidded to a stop as the ranchers holding the netting began to box the birds in. The birds filed back into the truck, and a race that may not have lasted more than ten seconds was over.

“Skeezix’s Big Bird!” boomed the announcer, declaring the winner. Fans stunned by the relative anticlimax — the time it took for the birds to line up and stop fidgeting surpassed the entire duration of the race — turned to each other, comparing notes on what they witnessed.

Afterward, the crowd continued to grow in size through the four horse races leading up to the Cameltonian. “It brings the kids out, and us old folks can bet on a race or two,” said Harry, a grandfather dressed in a lavender shirt and pleated khaki shorts, who was watching the races with his grandchildren. “I bet this place’ll clear out real fast once the camel race is over,” he added. He turned to look at the camels — the one in the outer lane, Camelot, had taken to walking around in circles as the other three waited obediently at the starting line. After a couple of loops, Camelot assumed the correct position — and without much warning, the Cameltonian began.

Hump Day seemed to take an early lead on the inside lane. But Camelot, in the outer lane, must have used the surprise start to his advantage; he and his rider sped past in the outer lane, and after another blink-and-you-missed-it distance on the track’s opening stretch, the camels, too, were finished racing. They slowed to a lumbering walk, and the four handlers led their charges through the winner’s circle, drawing louder cheers than most of the night’s other races. Camelot’s winning rider grabbed its reins and led it back out into the track, kissing his steed on the nose before heading to the stables.

Jared T. Miller is a multimedia journalist in New York.

New York City, July 21, 2014

★★★★ There was a little light in the sky when the artificial voice built into the portable speaker began announcing, loudly and repeatedly, that its battery was dying. There was full daylight when the alarm went off. Despite the promises on the front page of the newspaper, the air was damp, as if it had rolled in with the morning tide and up the island. Children were out wearing camp t-shirts or packing tennis rackets or dressed in dance clothes. Two sparrows had a dogfight in the air over the mouth of the West Fourth Street station steps, sending a feather pinwheeling down and away from them to the sidewalk. In the back room of the bar, the chess tables were still being set up. Further east on Third Street, sheets of sycamore bark lay in the planting beds and on the pavement and draped in the tops of the shrubs. The upper branches were bare waxy yellow. Out of the shade, the sky was full of glare. Clouds covered the midday sun for a moment, then let the shadows fade in again. The sky to the south was yellowish. In the later afternoon, pedestrians on Broadway were sluggish even as a sprightly breeze passed them. The room around the chessboards was still; the chess-campers were lingering somewhere out of doors. They returned at last in their own matching orange shirts, a bright file in the late sun.

The Legend of the Legend of Bunko Kelly, the Kidnapping King of Portland

by Elizabeth Lopatto

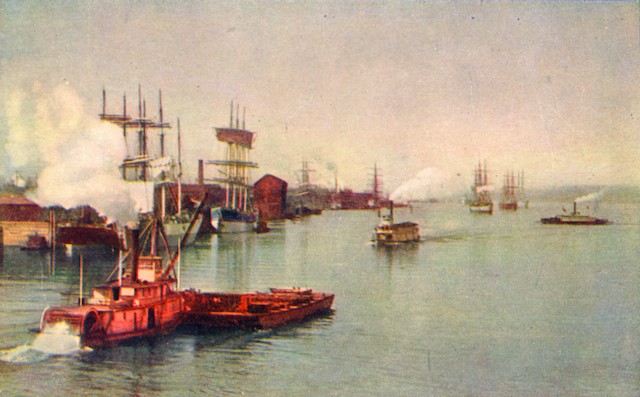

In the late eighteen hundreds, the port cities of the American West were dangerous nests of sailors, prostitutes, and gangsters — none more so than Portland, Oregon. The most infamous relic of those bad old days are not the wooly beards of its male population, but the Portland Underground, the city’s network of so-called “shanghai tunnels,” which tourists today are often told were used to spirit unsuspecting men, perhaps lured by a half-naked prostitute to an establishment where they were drugged and kidnapped, toward their final destination: pressed into service on a ship.

These kidnappers were known as crimps, and the “king of the crimps,” according to folk legend, was a man named Joseph Kelly. By his count, some two thousand souls owe their time at sea to him. Kelly spent his early life on the sea as well: In his memoir, he wrote of once being shipwrecked on the island of Madagascar. Rescued from the shipwreck by the natives, Kelly was fed soup. Afterward, he looked into the clay jug that stored the rest of the stew and discovered the right hand of one of his shipmates. When a typhoon struck, he and some other sailors followed the lead of a man described as an old pirate, and escaped from their rescuers; they were promptly picked up by pirates. Fortunately, Kelly and his band managed to lock the pirates in the ship’s belly before heading ashore in India.

In 1879, Kelly got off a ship in Portland. In those days, since sailors weren’t allowed to leave their ships until they reached their final port, many sailors disappeared when they arrived — fleeing for jobs in the local logging industry, for instance. About three-fifths of all sailors who arrived in Astoria or Portland ditched their ships. These desertions were a problem, since captains needed able-bodied men to set sail again. This gave rise to the crimps: If a ship needed to find more men, the captain sent for a crimp, who supplied bodies for up to fifty dollars a head. Kelly took up the trade and became so good at it that Stewart Holbrook, a “rough writer” who specialized in selling local Portland history to the reading public of the East Coast literary establishment, and Kelly’s somewhat besotted biographer, described him as “an artist, for the magnificent imagination he applied to his occupation was nothing short of creative.”

According to Holbrook, one October, while looking for seamen for a ship leaving the next morning, Kelley went through his usual stops on skid row — Erickson’s, Blazier’s, the Ivy Green, the Senate — and could not find a single man to press into service on a ship. Standing across the street from a cigar store, about to give up, Kelley noticed a wooden six-foot tall cedar statue Indian state outside; he wrapped the statue in tarpaulin and hauled it onto the ship’s bunk. After discovering the deception, the sailors threw the statue overboard. “Two days later,” according to Holbrook, “the Finn salmon fisherman of Astoria, a hundred-odd miles down the Columbia [River] from Portland, were astonished to drag in their nets and find a cedar Indian amid the struggling fish.” Kelly earned fifty dollars and the nickname “Bunko,” turn-of-the-century slang for a con man.

“Bunko Kelly” appeared in newspapers for the first time a few years later, according to Portland historian Barney Blalock: In April 1887, a ship’s captain wrote to the Oregonian to complain that Kelly had supplied him with a man who was rendered nearly motionless by rheumatism. By Kelly’s next mention, in 1890, a local paper described him as the “boss shanghaier in the Northwest.” But his most famous exploit was undoubtedly in 1893, when, according to Holbrook, Kelly was asked to supply the Flying Prince with twenty-two men, at a rate of thirty dollars per head. Kelly noticed an open trapdoor in a sidewalk — the kind that businesses without alleys use to take deliveries — and entered. Inside, he found twenty-four men; ten of them were dead. The group had tried to burgle the cellar of the saloon next door, but had broken into an undertaker’s shop instead; the keg they found and tapped was filled with embalming fluid. Kelly took the fourteen survivors and ten corpses to the ship, where he was paid for them all. The ship was already heading down the Columbia River when the corpses were discovered. They were removed at Astoria, Oregon, and the local papers soon caught wind of the tale, according to Holbrook.

At the time, crimping wasn’t illegal. But Kelly was eventually arrested for allegedly murdering G.W. Sayres, an opium smuggler who had been hacked to death and thrown in the Willamette River. Kelly had been fond of selling “opium” — actually clay — to the local Chinese population, according to historian J.D. Chandler, and had allegedly lured Sayres out of his home with promises of a scheme to raise about two hundred dollars by selling the fake opium, then beat him to death. Before Kelly was sentenced to life in prison, he declared his innocence and blamed the death on a frame-job by other crimps.

Kelly may have even been telling the truth. He had been working for Larry Sullivan, a prizefighter-turned-crimp; he was listed as a clerk at Sullivan’s Sailor’s Home at 113 North Second Street. By September 1894, though, Kelly had broken away from Sullivan and gone into business with someone else, renting a flophouse that was used as a boarding house on B Street. Sullivan took this poorly: Three days before the murder, Sullivan, Kelly, and two other men were taken to jail for what the local news reported was “a lively street fight.” While Kelly maintained his innocence, his story often varied: sometimes he was being framed by Sullivan; other times, he had been hired by a Portland attorney with the Pynchonian moniker of Xenophon N. Steeves, but merely to kidnap Sayres, who was pursuing a case against one of Steeves’ clients. It took a jury twelve hours to find Kelly guilty of murder in the second degree.

While in prison, Kelly wrote the memoir Thirteen Years in the Oregon State Penitentiary, in which he claims to have fought in the American Civil War (with the Southern navy, against the North), a Cuban uprising, and in Chile, where Kelly says he was part of “a regular monthly effort to overthrow the government,” working the gun turrets of a ship called Wanda that had been bought by revolutionaries.

The book didn’t sell. By the time Kelly was released in 1908, he’d been largely forgotten. He made an appearance that same year in San Francisco, when a report in the San Francisco Call stated that he worked for gang boss Abe Ruef, who was on trial for bribery: “Bunko Kelly, another undesirable, who openly reports to Ruef’s office boy, Charley Haggerty, during recesses of the court, was also present.” After a book tour in Seattle the following year, he wasn’t heard from again.

Here’s the problem with the legend of Bunko Kelly: There’s no record of either the cigar store Indian or the Flying Prince incidents. There’s no mention of a ship called The Flying Prince in the records of Lloyds of London, which insured most ships’ cargo. In fact, Kelly likely wasn’t even born in Liverpool, which is usually cited as his hometown; prison records indicate he hailed from Connecticut. The story about cannibals is so absurd that it can only be taken for a joke — after relaying it, in Thirteen Years in the Oregon State Penitentiary, Kelly says prison is worse.

Kelly does appear in the official court records — crimps often used the courts against each other — such as when, in April 1887, he took his own brother to court over a fifty-dollar debt, though he apparently remained in partnership with him. A story in the Oregonian in 1889 recounts complaints of a Samoan sailor, who said Kelly had locked him in a room when Kelly couldn’t find a ship that would readily take him. In 1891, he was arrested for keeping a “disorderly house,” according to Blalock, which could have merely meant an unlicensed saloon, but which may have also meant that he was running a whorehouse.

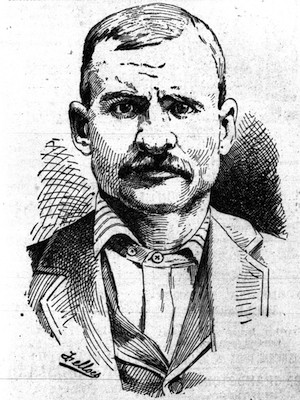

“It is my personal conviction,” Blalock writes in The Oregon Shanghaiers, “that had Bunko remained simple ‘Joe Kelly’ and not stumbled on a memorable name, had he not been convicted for a vicious murder, he would be no more likely to be remembered than any of the hundreds of bunco steerers who blew through Portland back when the city was ‘wide open.’” The real Kelly, writes Blalock in Portland’s Lost Waterfront, was “a cheap man who could make even an expensive suit look cheap. He smoked nickel cigars and slept in cheap rooms. He was a ‘blow hard’ who told ‘fish stories’ and worst of all, his word was worthless.” While Kelly is almost invariably described as being “squat” and “barrel-chested,” a sketch from his murder trial, drawn by a Portland Evening Telegram staffer, shows a man with hair loss along the temples, a heavy mustache lying across a broad, square face with a wide jaw, and a skeptical expression.

The article that made Bunko Kelly famous, published in The American Mercury, was not the first time that Stewart Holbrook had told the Flying Prince story. Sixteen years earlier, in the Oregonian, the gist of his tale was basically the same, but slightly more outrageous: Forty men are found by Kelly in the undertaker’s basement, not twenty-four. Unlike in the more famous account, however, Holbrook confesses to the reader the story may be just that: “I don’t know for certain if the story’s true, but it’s one you’ll hear from any of the old-timers.”

Prior to becoming the biographer of Bunko Kelly, Holbrook wrote a series of books about Washington, Oregon and Idaho, with a focus on the oral histories of the working class. A former lumberjack, his first job as a writer was with the Works Progress Administration in 1932, where he edited two million words on Oregon history. After that, he wrote his first book, Holy Old Mackinaw: A Natural History of the American Lumberjack; the oral histories, combined with Holbrook’s own experience with the WPA, made for a bestseller. He ultimately spent three decades at the Oregonian, making his living writing stories like that of The Flying Prince, and founded the James G. Blake Society, a jokey organization whose main goal was to prevent people from moving to Oregon.

One of Holbrook’s primary sources of the oral histories that his work relied on was Edward “Spider” Johnson, a bartender at Erickson’s Saloon, an establishment that claimed its bar was the longest in the West; Johnson’s stories were apparently too good to check. According to Blalock, “During the years he was supposed to be sparring with [Portland boxer] Jack Dempsey, hanging out with crimps and working as a sailor, records show [Johnson] working the printing presses at W.C. Noon Bag Company.” Nevertheless, Holbrook sold Johnson’s story to publishers, including the Atlantic Monthly; his piece “The Three Sirens of Portland,” published in The American Mercury in 1948, also owes its genesis to Johnson. Over time, Spider Johnson’s tales became enshrined fact in Portland mythology; some are even repeated in history books, Blalock notes.

But what about the reports of the Flying Prince? Holbrook’s account, republished in Wild Men, Wobblies and Whistle Punks by the Oregon State University Press, says specifically that the dead men “made a great rumpus in Portland,” and that Astoria newspapers “soon had the story on the wires.” If Spider Johnson’s story was true, writes historian Finn J.D. John, the newspapers of the era were oddly quiet about the incident. No reference to the Flying Prince occurs in either the Astoria or Portland papers from 1893, and no one mentions it in the coverage of the murder trial. Still, John’s remarkably optimistic about that story. “Most likely,” he writes in his book, Wicked Portland, “the story has at least some basis in fact.” It had widespread currency in the 1930s, when there were still plenty of people around who remembered the 1890s. John’s theory is that men were drugged by Kelly — who had a special concoction of knock-out drops called Kelly’s comforters — and shanghaied, though perhaps Kelly misjudged the dose on at least one occasion, and wound up with several dead would-be sailors.

The reality of the shanghaiing era in Portland was arguably even more sinister any tale about its tunnels: The crimps often didn’t use them because they didn’t need to. The most powerful crimps could kidnap someone at noon on a main street, and so long as the person wasn’t of social standing in Portland, no one cared; even someone as relatively unimportant as Bunko Kelly could operate unimpeded. Crimping was finally made illegal in the U.S. in 1915’s Seaman’s Act, but by then the practice was already dying out — the advent of steam-powered vessels meant that the need for unskilled labor on ships dropped drastically.

Today, Hobo’s Restaurant and Lounge in Portland offers tours of its “shanghai tunnels” for $13 per adult and $8 per child. You can make your reservation online.

Elizabeth Lopatto is a science writer based in Oakland. She likes philosophy of science too much for her own good. She’s on Twitter.

Images via Wicked Portland

Everything You Have Needed to Know in 2014 (So Far)

Today, in the Washington Post, Eve Fairbanks asks:

Could “all you need to know” be the most insidious, reductive, and lame story formula currently conquering our reading life? Everywhere you turn there’s another purported ne plus ultra explainer purporting to tell us “absolutely everything we could possibly need to know” about some current event, some curiosity of history, some deep mystery of life on Earth.

Good question! “All you need to know” can be distilled down further to the no-less-demanding formulation of “need to know.” It’s still just as chiding, just as exhaustive, just as needy, when you consider the full range of its implications: You are required to know what is in this document in order to be a complete human; what is contained herein is Soylent for your brain, the stripped down, crucial bits required for intellectual survival; and all knowledge that exists out of this space about a given topic (or anything, really) is wholly unnecessary. Once the diktat of “necessary knowledge” has been whittled down to its core, the true scope of its permutations can reveal itself in full.

And there are so many things to know. Here is everything (or at least most of the things, since I gave up fourteen pages into the Google search) that you have needed to know in 2014, according to the Washington Post:

July 22

What you need to know about the AFC East

What you need to know about the NFC North

What you need to know about the AFC North

What you need to know about the NFC East

July 20

What Metro riders need to know for Monday

July 18

What you need to know about Boehner’s plan to sue Obama

A Florida judge just voided the state’s congressional districts. Here’s what you need to know.

July 3

This tweet tells you everything you need to know about how Hobby Lobby fits into the 2014 election

July 2

Everything you really need to know about Songza (… and every other music-streaming site)

What you need to know to have a fabulous July Fourth in D.C.

July 1

Everything you need to know about the SCOTUS contraception ruling

June 29

Missed the Sunday shows? Here’s all you need to know.

June 15

Everything you need to know from the Sunday shows in 5 videos

June 11

Here’s what you need to know about the men who could become Afghanistan’s next president

June 10

Here’s what you need to know about Donald Sterling’s lawsuit against the NBA

June 9

Five numbers you need to know from the Veterans Affairs department audit

June 4

Everything you need to know about California’s primary results

June 2

Everything you need to know about the EPA’s proposed rule on coal plants

May 30

Everything you need to know about the VA — and the scandals engulfing it

May 29

The five things you need to know about Snowden’s first U.S. television interview

Everything you need to know about Michelle Obama’s school food fight

May 28

Four things you need to know about the guy who beat Ralph Hall

May 23

The 10 things you need to know about Julian Castro

May 19

Everything you need to know about the alleged Chinese military hacker squad the U.S. just indicted

May 17

What you need to know about Julián Castro, the likely next head of HUD

May 16

Everything you need to know about Ohio Governor (and maybe 2016′er) John Kasich

May 15

Fall 2014 TV schedule: Snapshot of everything you need to know

Today, the FCC will vote on the future of the Internet. Here’s everything you need to know.

May 14

Everything you need to know about U.S. health, in 8 charts and 3 paragraphs

Everything you need to know about primary day in Nebraska and West Virginia

May 12

Primaries everywhere! This chart tells you the ones you need to know.

May 7

What you need to know about Jack Ma, the founder of Alibaba Group

May 2

Everything you need to know if you’re heading to Nationals Park on Saturday

Everything you need to know about betting on the Kentucky Derby

May 1

Everything you need to know about executions in the United States

April 28

What you need to know about the Fed’s meeting this week

April 25

Five things you need to know about the Northwestern union vote

April 24

Everything you need to know about Capital — the hot summer beach read

April 23

Everything you need to know about popes and saints

April 22

Everything you need to know about Aereo, the Supreme Court and the future of TV

Everything you need to know about today’s Florida special primary election

Everything you need to know about the D.C. license changeover

Everything you need to know about the latest round of Supreme Court cases

April 15

Everything you need to know about the long fight between Cliven Bundy and the federal government

What you need to know about Stephen Colbert taking over the ‘Late Show’

April 4

What you need to know about the policy fallout from the Fort Hood shooting

April 3

What you need to know about the Supreme Court’s new money-in-politics decision

March 27

Everything you need to know about CAT, the Secret Service’s baddest bad boys

What you need to know about the latest health-care delay

March 24

Everything you need to know about the Washington landslide

Here’s what you need to know about the Hobby Lobby case

Everything you need to know about the Brown-Shaheen ‘People’s Pledge’ ruckus

March 19

Nine things you need to know before filling out your NCAA tournament bracket

March 18

Everything you need to know about Michelle Obama’s trip to China

March 12

What you need to know about the Federal Reserve’s new cast members

March 11

Everything you need to know about today’s special election in Florida

March 10

Everything you need to know about Apple’s latest iOS 7 update

Everything you need to know about what happened at CPAC

March 5

Everything you need to know about Obama’s budget

What you need to know about the SAT

March 4

Seven things you absolutely need to know about Obama’s budget

February 27

Everything you need to know about Google Glass

February 26

Everything you need to know about this year’s Oscar nominees, in less than six minutes

February 19

What you need to know about the CBO’s minimum-wage report

February 18

What you need to know about Ukraine

February 7

What you need to know about Putin’s popularity

January 22

Everything you need to know about the Chris Christie investigations

January 18

Everything you need to know about Common Core

January 17

Everything you need to know about Obama’s NSA reforms, in plain English

January 14

What you need to know about the omnibus appropriations bill

January 10

Target breach: What you need to know

January 9

The 10 things you need to know about Bridge-gate

January 8

Everything you need to know about the war on poverty

January 2

All you need to know for wild-card weekend

January 1

Everything you need to know about life under Obamacare

I’m sure there will be more things we need to know in the coming days.

Image of a bear who knows everything he needs to know by Cloudtail

History Recorded

Hacked? EPA Office of Water tweets about Kardashian App

EPA tweet about Kim Kardashian confuses and entertains the Internet

Kim Kardashian App Takes Over Environmental Protection Agency’s Twitter

EPA Office of Water Is Caught Playing Kim Kardashian Mobile Game

Kim Kardashian App Takes Over Government Agency’s Twitter Account

EPA tweets about Kim Kardashian, old congressman gets confused

EPA tweet baffles: ‘I’m now a C-List celebrity in Kim Kardashian: Hollywood’ iPhone game

The EPA just can’t seem to get enough of the Kim Kardashian app

Hacked? EPA’s Office of Water tweets about Kim Kardashian app

EPA sends tweet about Kim Kardashian game

For Some Reason, EPA Water Tweeted About Kardashian App Tonight

EPA Office Of Water Tweets About Kim Kardashian App

Kim Kardashian’s App Gets Tweeted By the EPA Because the Kardashians Run the Government

All The Coolest U.S. Government Staffers Are Playing Kim Kardashian’s iPhone Game

EPA Gets Caught Playing ‘Kim Kardashian: Hollywood’

EPA Office of Water caught playing ‘Kim Kardashian: Hollywood’ in embarrassing tweet

Rep. Dingell checks in on EPA after Kim Kardashian tweet

EPA: Protecting Our Water, Doing Okay-ish on Kim Kardashian Hollywood

EPA sends out tweet promoting Kim Kardashian game, apologizes for doing so

Thomas Berger, 1924-2014

“More than anything, the paradoxical logic by which Berger unfolds his scenes connects him to Kafka. Too many contemporary writers kowtow to Kafka in mummery: ostentatiously dreamlike settings, Shadows and Fog-ian Eastern European atmosphere or diction. Berger engages with Kafka’s influence at a more native and universal level, by grasping the way Kafka reconstructed fictional time and causality to align it with his emotional and philosophical reservations about human life. Berger’s tone, like Kafka’s, never oversells paranoia or despair, and the results are, actually, never dreamlike. Instead, Berger locates that part of our waking life that unfolds in the manner of Zeno’s Paradox, where it is possible only to fall agonizingly short in any effort to be understood, or to do good.”

— Jonathan Lethem wrote this about the great Thomas Berger over a decade ago. Berger died earlier this month. This is his most famous book, and it’s probably still a good starting point, but this is pretty great too. Also: the rest of them. Berger was 89.

New York City, July 20, 2014

★★★★ Bubbles drifted west on 68th Street in the sunshine. Wheeled conveyances were everywhere: scooters, bicycles, strollers, a wheeled walker. The two-year-old weaved upstream on his scooter through an oncoming line of them. He rolled expectantly up to the fence of the playground, missing the gate, looking over his shoulder at a pony-sized Parks Department garbage truck. Two games of frisbee were going on in the open schoolyard, and a boy in an Eli Manning jersey was place-kicking a football off a tee into the fence. There was humidity on the air, but still it was cool. After the playground and a long, sunny uphill, hot vapor was rising through the vent holes in the crash helmet. He woke from a nap with his head drenched in sweat, the pillow puddled with it. Down the river, in a bleary haze, a cruise ship was slowly heading off. Toward the day’s end, the humidity was gone, the sky cloudless, the air near crispness. It was a little chilly for shorts, though it would have been ludicrous to call that discomfort. The sun was still warm on the nape of the neck, even on the rebound from windows on the far side of Columbus and Broadway. Ugly steel balcony railings looked like smoked glass. Groups had formed discussion circles on the edge of the artificial grove at Lincoln Center; one participant, in a surfeit of abandon, was stretched out prone on the hard pavement. The western sky at dinnertime had one swath of tiny clouds in it, strewn like barely cracked peppercorns. The sun had declined enough now that the two-year-old could no longer object to it shining in his face at the table, though if he fidgeted far enough back in his chair, he could play with his silhouette and complain or marvel that it had no eyes.

Selfies from the 9/11 Memorial

by Leah Finnegan

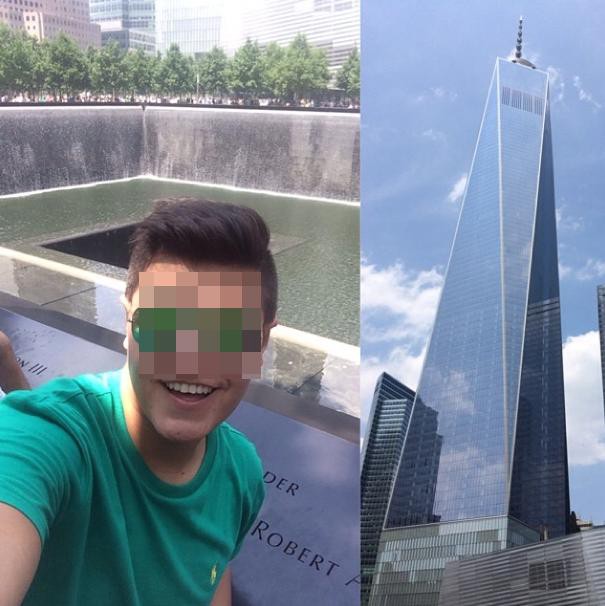

On a recent afternoon, an older man and woman self-consciously configured themselves in front of the south reflecting pool at the 9/11 Memorial. The man placed his hand on the woman’s hip in an awkward clasp and grinned broadly as another person took their picture with a digital camera. A girl in a Yankees cap took a selfie with her camera phone, the Freedom Tower soaring into the sky behind her, the reflecting pool draining into nothingness. She was smiling. An Ethiopian man asked me to take a photo of him and his family. They wore blank expressions, though the youngest girl with them hammed for the camera with her scooter.

The 9/11 Memorial, officially titled “Reflecting Absence,” is a superlative site. It is the most expensive memorial in America, at a cost of five hundred million dollars (up from a preliminary estimate of a hundred and seventy-five million dollars). The two reflective pools are built in the footprints of the twin towers, and contain the largest man-made waterfalls in the country. The contest for the memorial design yielded more than fifty-two hundred entries from sixty-three countries. Other ideas included towers built from Lego blocks and clocks stopped at 9:11. Michael Arad, an architect from New York, won the project, along with Peter Walter, a landscape architect.

The south reflecting pool of the memorial gets considerably more traffic than the north pool. Panel S-38, at the southeasternmost corner of the south pool, near the memorial’s entrance at Liberty and Greenwich streets, sees a bounty of visitors, probably because it’s closest to the entrance. Children climb on it. Families pose for photos. Tired tourists hang their bodies on the marble slab, obscuring the panel’s names — Sebastian Gorki. Hernando R. Salas. Joni Cesta. The memorial, as it stands, often functions more like a tourist rest stop than a place of somber reflection. When I visited on an oppressively hot early July day, visitors dipped their hands into the reflecting pools and poured the water onto their heads and legs to cool off. They leaned on the marble panels with the names of the dead to eat snacks, even though there are no food vendors or trash cans allowed on site.

Whatever tourists’ regard for the sanctity of the space, photographic devices occupy the hands of the young and old visitors alike. Taking a photo at the memorial might as well be one of the memorial’s numerous rules, right next to the one prohibiting soap (no bubble baths in the fountain). Visitors from all over the world readily post photos of the memorial to social media. One photo on Instagram features a smiling couple in sunglasses in front of one pool. You can see the name “James,” and part of what appears to be “Christopher,” on the panel behind them. The caption reads, “Enjoying New York before the missionaries arrive tomorrow!” Another user appears to be on a date: A picture of her and a man in front of one of the pools is captioned with “City date with this kid [heart emoji].” One person left a comment on the photo: “ADORBS.”

A popular hashtag on 9/11 memorial photos is “#speechless.” The caption for one photo reads, “Such a touching place,” followed by a crying emoji. Visitors often wedge white roses into the names that are etched into the marble panels; these are popular for subjects for photography. “Rest in peace [flower emoji],” one user wrote. On another rose photo, someone commented: “Why’d you put a piece of popcorn on the names of people that died? Is that symbolic of something?” The photographer replied: “it’s a rose dude…”

Discussing my visit to the memorial with a friend, he asked, “Why does the 9/11 memorial allow people to treat it so casually?” This question has stuck with me, especially as I consider the memorial in light of my recent visit to the Auschwitz Memorial and Museum in Poland. Of course, in one sense, the two sites could not be more different: Auschwitz is a fairly depoliticized memorial of evil, a place where millions of people were systematically tortured and murdered over the span of years; the 9/11 Memorial is a highly politicized ground where thousands were killed in a few unforgettable hours. At Auschwitz, the remains of horror confront the visitor. At the 9/11 memorial, what little is left as evidence of that day is contained in a museum that is buried seventy feet beneath throngs of tourists.

After visiting Auschwitz in June, I argued that photographing and sharing pictures of places where atrocity has happened — specifically, Auschwitz and Birkenau — was essential for recognizing and acknowledging that history.

We should keep posting — and sharing — photographs of places where horror has happened until these places inevitably disintegrate, even if the photo of such a place does not fit so neatly into a social network, where the crass language of the sharing community — “likes,” “hearts,” “selfie,” “re-gram” etc., etc., can denigrate the austerity of an image. If we use social media for only the happy or banal events in life — weddings, brunches, signs with terrible grammar — well, why bother?

The 9/11 memorial makes me reconsider that thesis, if only because it feels built to be photographed. It’s glitzy, tactile, antiseptic and commercial all at once.

Photographs in the immediate aftermath of 9/11, unlike those of the Holocaust or other atrocities, often did not explicitly show the dead; the event itself utterly annihilated most traces of human existence. (Also, the event itself was photographed, videoed, broadcast and rebroadcast; the plane going into the second tower is like a .gif branded into our collective conscience.) As Susie Linfield, a photography critic and New York University professor, noted in Guernica, a photo of a “severed, bloody, shredded leg and foot lying on the pavement” at a 9/11 photography exhibition was “shocking because it is so grisly, but also because it is so rare.”

Instead, as Linfield has said, photos of 9/11 mostly show New Yorkers coming together. “What 9/11 did produce was a lot of citizen documentation in the days following the attacks,” she told the History News Network. “These were not photographs of the attacks themselves, but depictions of how we as New Yorkers tried not only to survive, but also to help each other and to come together to understand what was happening.”

Building a memorial is not a panacea to processing the ills of history; only time can accomplish that. Major controversies in regards to the memorial at Auschwitz persisted well into the nineties; now that there are so few Holocaust survivors left, the museum is grappling with how it will carry into the future without them. But it’s interesting, and necessary, to consider how the 9/11 Memorial’s infancy sets it up for later life.

Across social media, photos and tributes to 9/11 are pervasive, especially as the anniversary of the attacks dawns each year. Last year, on the twelfth anniversary of 9/11, Instagram’s official blog alerted users to the hashtag #tributeinlight to find pictures of the massive beams of light projected in place of the towers. Mashable, the technology blog, encouraged Instagram users to follow the hashtags “#neverforget, #Remember911, #FreedomTower, #911memorial and #AlwaysRemember” for “more powerful images” (what those are, exactly, who can know?).

There’s something uncomfortable and perhaps uncouth in these recommendations, inasmuch as they don’t motivate users to process the events on their own terms, while the directive is doubly disagreeable because it comes from the corporate entity itself. Would Instagram sponsor a hashtag to mark the anniversary of the liberation of Auschwitz? (Maybe?) How is it decided where the line is drawn?

The memorial’s Twitter stream, which has 43,400 followers, stays relentlessly on message: Somber positivity. No politics. America. Most every tweet is some form of the same: Retweets of visitors who call the memorial “beautiful,” “gorgeous,” and “so moving!” One retweeted comment reads, “Visited WTC site today and @Sept11Memorial. Very moving and a big crowd paying respect. We’ll certainly #neverforget!” Recently, the feed touted the 9/11 Museum’s display of the bullhorn George W. Bush used to talk to first responders at the site (on loan from the George W. Bush Presidential Library in Dallas). Once, it retweeted former mayor Michael Bloomberg cheering for the U.S. soccer team.

There are not many choices at the 9/11 Memorial, engendering the feeling that there are not many choices in how one can respond to 9/11. Must you be #speechless? Must you gaze in awe at the towering column of the #FreedomTower? “Expressive activity that has the effect, intent or propensity to draw a crowd” is forbidden (except by permission). The entire area, with its looming police presence and forebearing architecture, is oppressive. It’s almost as if the site induces you, with its stringent rules and inhospitable nature, to give up on thinking about it and just lazily photograph it.

According to Linfield, photography can be a defense mechanism when people visit monuments to atrocity. “Perhaps people are shielding themselves from contemplating the horror of the event by photographing it — and photographing themselves at it,” she wrote to me. “This seems like a way to diminish experience, to diminish history, to diminish doubt and uncertainty and contradiction and thought — and hide behind the camera instead.’”

For many people, that may be true. Certainly, at Auschwitz, I felt the need to hide behind my camera at some moments. But at the 9/11 Memorial, I mostly felt uncomfortable. I wondered if you could be suitably and privately horrified by 9/11, but also use the memorial as a grounding for your own politics or feeling about America and terrorism and the people that died. The answer seems to be no. The only acceptable politics is the one dictated by the memorial. The cost of this rigidity is the ultimate vapidity of the site: the ice-cream eating tourists using it to bathe.

As Michael Kimmelman, The New York Times architecture critic, recently noted, the memorial is somewhat awkward. It’s not representative of New York. “The place doesn’t do much to celebrate the city’s values of energy, diversity, tolerance openness and debate,” he wrote. It will take time, perhaps, for this to happen. Maybe it’s a good sign that people are going on dates at the memorial. Maybe that’s a sign of normalcy. It’s definitely a sign of life.

But what does it say about the framework in which we consider 9/11? It’s carefully considered and didactically controlled. As with a photo on Instagram, you have two options when it comes to the memorial: Like it, or say nothing.

Previously: Instagrams from Auschwitz

Leah Finnegan is a journalist and the editor-in-chief of leahfinnegan.com.