New York City, July 24, 2014

★★★★★ The rain had washed away the haze, though if it had done anything even briefly about the garbage, the smell had already regenerated. Sex parts drifted down from the honeylocust trees. The clouds overhead were a smooth filter on the sun; off in the east, they stood out darker and individual. The temperature was uncannily mild and relaxing, a waking dream state. Outside a bodega, a sturdy man tried a pogo stick, not at all competently, the spring groaning. The late day brightened up in all directions. An gorgeously ordinary tree flared green against an opulently ordinary brick wall. Uptown, pigeons divided a chicken tender among themselves on the Broadway sidewalk. The seven-year-old retrieved a penny from their midst. The clouds piled up gray-blue in the west, where the descending sun could and did spray and pour and splash colors over them, ending with a pink rind along the cloud tops. Sleep arrived with a breeze through the opened bedroom window, under a ruddy night sky.

The Gee Whiz Train

The thin, fragile, and (oft unfairly) maligned conduit between Brooklyn and Queens is shutting down for five weeks so that the MTA can repair lingering damage from Hurriance Sandy. This has provided occasion to air out moldering anxieties about the G train and the area it serves, one too ripe for Uber to resist exploiting:

While the MTA does their thing, we’re here to bridge the gap with one free transfer between the Nassau Av and Court Sq G train stops.

The MTA’s “thing” is maintaining vital physical infrastructure. Uber is beloved by its investors precisely because it does not perform that kind of costly work, but capitalizes on making what someone has already built more efficient through software — putting bodies in empty seats — then collects the freshly excreted capital from that process. Of course, this is no reason not to enjoy that free ride! It’s already been paid for, and we can’t leave all those poor UberX drivers, whose rates were recently cut, with empty seats. It would be so terribly inefficient.

Photo by Ed Yourdon

A Poem by John Ashbery

by Mark Bibbins, Editor

The Undefinable Journey

Where do you think you’re

going to get lines to

punish the stranger with?

Cursing, destiny’s piñata;

it’s a surprise! (Partly sunny.)

O neat-o friend of mine,

to add a central target to the

mix is not to chase sea

monsters, real or imagined.

You drop the floor.

Small white chicken friends,

like life itself

over time last night…

And, what have you done with this one?

John Ashbery’s new book of poems, Breezeway, will be published next year. A two-volume set of his translations (poetry and prose) was published in early 2014 by Farrar, Straus & Giroux.

You will find more poems here. You may contact the editor at poems@theawl.com.

Space Invaders

by Betsy Morais

Tourists are freaks. (For context: I work in Times Square.) Tourists are unnatural to the environment into which they insert themselves; they walk funny; they talk wrong. David Foster Wallace wrote (in a footnote) that to be a tourist “is to spoil, by way of sheer ontology, the very unspoiledness you are there to experience. It is to impose yourself on places that in all noneconomic ways would be better, realer, without you.” Something similar might also be said of journalists, who also insert themselves awkwardly on someone else’s turf. But the journalist, if we’re being high-minded about it, serves some civic or artistic purpose; the presence of the tourist is for the sheer sake of personal amusement. That is to say, the mission of a tourist is selfish, and with that comes a degree of indulgence — even a sense of entitlement, which maybe is necessary to function in a situation where, as a tourist, you know you don’t really belong.

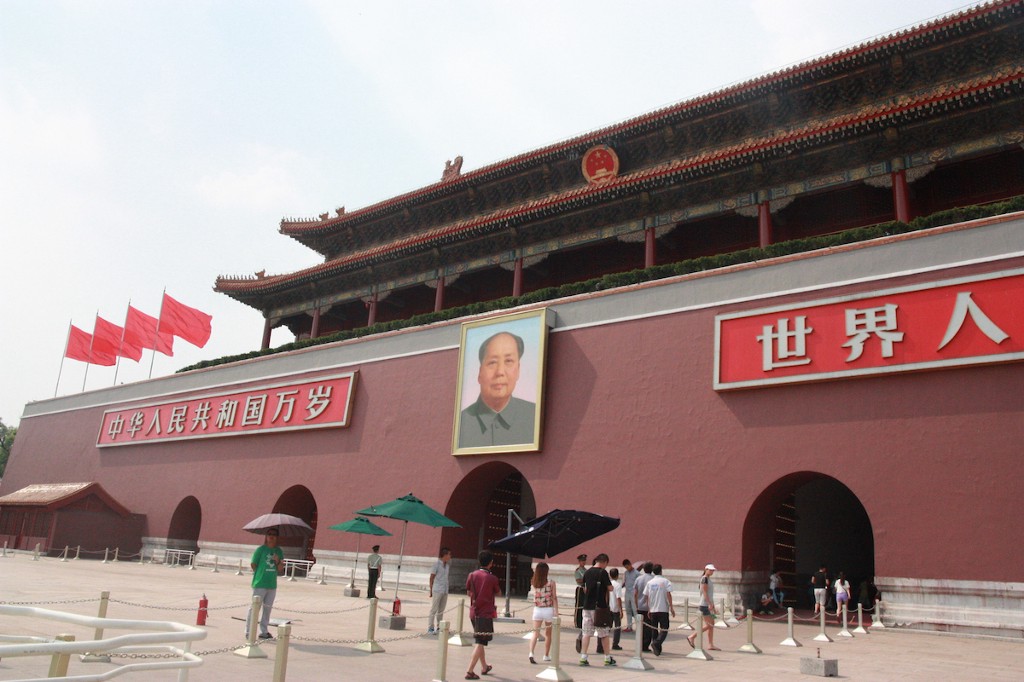

I was a tourist in China for two weeks. I bopped from one landmark to another, squeezed into the subway, and did my best to avoid restaurants patronized by anyone who looked like me (i.e., non-Asian). Being an American tourist made me a burden as well as an object of fascination. I found myself, as a novelty, the unexpected beneficiary of attention and perks: somebody in Yunnan province asked where I was from, and then requested a picture; at a hot pot place in Xi’an, where there was an hour wait for a table, my group was told, through my Chinese-speaking college friend, that we could be seated right away because we were foreigners — we were “special.” Before we could protest, the waitress whisked us to our seats — past a row of disgruntled hungry people — and gave us small plastic bags to protect our phones and a cloth with which I could wipe steam from my eyeglasses. This sort of treatment was the opposite of what I would have expected from anyone forced to serve a tourist: not only was it encouraging of our trampling all over someone else’s night out to dinner, it was downright obsequious. Tip was included, so that wasn’t a motivating factor. Awkward as this should have been, it wasn’t — tasty, fun, kid-friendly, recommended! — because that is the essential contradictory nature of the tourist.

There were also moments when my relatively harmless cultural trespassing, of a kind familiar to visitors everywhere, felt China-specific. I brushed up against an over-regulated society’s unsticky red tape, which falls away with the slightest pleading, or the smallest bribe. When there are so many rules, none can be held so firmly in place — everything is up for negotiation, if you know how to approach the transaction. My host in Beijing, a friend who grew up there, deftly navigated the complexities of requests and winks and cash offerings, because she spoke the language and she knew instinctively how to work the angles. My American Chinese-speaking friend watched in awe of her craftiness; in China, it can be difficult to know where the line is, and, yes, the closer you come to crossing it, the greater the risk of punishment, but also, the more you see how arbitrary and meaningless it is. Dancing around that line is the only way to get anywhere you really want to go. And if you are an American tourist, this makes trespassing all the more enticing.

One night, after dumplings, my friends and I went to visit the Olympic Park, built when the city hosted the games in 2008. As we approached, we saw a glowing blue rectangle, which looked at first like water droplets painted onto the black skyline. It was the National Aquatics Center, better known as the Water Cube. Michael Phelps won eight gold medals in there. We were drawn toward the bright pulsating wall, stomping ahead with determination, waving away one insistent scammer after another, all trying to make a buck by taking our picture. “You must do it now, before they shut the lights off!” one shouted. We shook our heads. But as we neared the edge of the park, we realized it was nearly closing time. A second after I got the critical iPhone shot, the lights flickered to a dim, purplish gray. But then it turned yellow, and gray again, and returned to blue, as if the cube hadn’t given up on us yet. Another salesman appeared, offering a photograph. We asked if he could get us inside. The Beijinger went several rounds with him, as he gesticulated toward a part of the fence hidden by a bush. If we gave him eighty yuan, he’d get us in the park. The Beijinger talked him down to forty. He nodded, led us around a corner, lifted back the bush, and loosened a tall grated gate with a shorter fence behind it. We climbed over the short fence, and then a second, and there we stood, basking in the blue light. It flickered again. We followed a path around the side of the building, toward a wide courtyard, where there were still vendors selling trinkets — a soldier that crawled while holding a Chinese flag, a neon top that leapt in the air. There, we faced Beijing National Stadium, or the Bird’s Nest, as it’s known. It is a magnificent modern structure, a deconstructed stadium hive with steel beams swirling around. It was designed by the Swiss architects Jacques Herzog and Pierre de Meuron, with artistic consultation from Ai Weiwei. Lit against the darkness, it looked like the path of wind around a spinning ribbon. We stared up at it admiringly, took pictures, and slowly gravitated toward the entrance. As we did, the lights went out all across the park. Only one overhead lamp was on — just enough to for people to see their way out.

We didn’t move. The Bird’s Nest was closed off by a gate that met in the middle by a rolling divider. It wasn’t locked. Behind it, sitting in a folding chair pushed up against the exterior wall, was a man in black, his head down, in shadow. The other non-Chinese speaker among us leaned on the divider, easily pushing it ajar. He grinned. He stepped through, and began to walk towards the man, who did not acknowledge him. Finally, the Beijinger called out, in Chinese, “Excuse me, sir?” The man looked up. He rose from the chair and approached us, saying, “you are not allowed to be here.” But as he said so, he didn’t move the divider. And he didn’t say another word as we each passed through it. He just shrugged, and returned to his post. We walked through the front door, which was open. On either side was a parking lot; straight ahead, the escalator was running. Without saying a word, we got on. First floor, second, until we reached a landing. There, in a room with rows of movie-theater seats, a man was taking a nap. We entered and saw, to our right, a door to the stadium seats. The man was roused from his slumber. “You are not supposed to be here,” he said, matter-of-factly. The Beijinger smiled at him and pointed to us, her American friends, saying in Chinese, “They have come such a long way, and they will be so disappointed if they cannot go inside.” Her expression was a little shy, a little flirtatious, totally unthreatening. The man nodded. We continued through the door. There we saw, with the lights still on, the the green Olympic turf. Aside from a few building staffers sprawled out at the corner of the track, we were the only people inside. We looked out from the center of the field at the empty stadium — with some eighty thousand vacant red seats — and waited for the police to come barreling in to arrest us.

But the security officers never came. No one bothered us. We stood in peace, taking photos and laughing in disbelief at our luck. The Americans did, at any rate. The Beijinger said she wasn’t shocked in the least. “There are rules and you are meant to push them as far as you can go,” she said. Nobody minds until they mind, and you won’t know if someone minds until they come for you with handcuffs. If they don’t, the guards couldn’t care less — and why should they? They’ve got to sit around all night with nothing to do. We couldn’t post our excitement to Twitter (blocked) or Facebook (blocked) but, when we tried to imagine what would have resulted from a similar attempt at Yankee stadium, we scoffed at the absurdity of such an idea.

A few days passed. We went to the Great Wall, to one of the “wild” parts that has not been renovated by the Chinese government and hence is not open to tourists. (We got there via a guy named Mr. Chen, known by one of the Beijinger’s adventurous friends.) The word “authentic” was thrown around as we climbed across. Five hours later, when Mr. Chen dropped us back at the edge of the city after a long trek, we were sweaty and covered in dirt. We entered the subway, bought our tickets, and began to make our way down, but two security officers stopped us. They shouted something at my Chinese-American friend, assuming he had a Chinese identification card. The Beijinger tried to explain the situation, but they shouted more, demanding to see our passports. We didn’t have them with us, so we handed over our drivers licenses. Two were from New Jersey, one was from Massachusetts; they don’t look that similar. Not that the Chinese police would know the difference. The two men (one of them, I noticed, was wearing Birkenstocks) inspected the I.D.’s and gave me a feeling I hadn’t had since I tried to enter a bar during my sophomore year of college. I stood frozen for a couple minutes, fearing this would be the end of my trip — that this was the result of my recklessness at the Olympic Park, that I had crossed the line from tourist to a pawn in some diplomatic revenge plot. And then, without looking in my direction, the officers returned our I.D.’s and grumbled something to my Chinese-American friend. I was flustered and angry. “Why did that just happen?” I wanted to know. The Beijinger led us off. “They just need to prove that they are doing something,” she said. “For the cameras.” For that, I couldn’t blame them. There was a ring of familiarity in that, for the tourist.

Betsy Morais is on the editorial staff of the New Yorker.

The Book I Didn't Write

by Elmo Keep

I didn’t write the book because the thought of it made me feel vaguely ill at all times. Even when I wasn’t thinking about it directly I was thinking about it. None of the thoughts were good.

I didn’t write the book because it was a book about betrayal that could only be facilitated by my betrayal of other people, many of whom had already been betrayed. This wouldn’t have been a clever metatextual commentary on the nature of betrayal; it would have just been really quite mean of me, and sad.

I didn’t write the book because I thought that in the end it would not be interesting. Every day I wondered who would care about the story. There are only so many books that each of us can read in a lifetime; why would this book be one of them? The enterprise of writing — or not writing — the book took on the tenor of the absurd in my mind because it would have hurt no small number of people, and for me to dig around in their lives to turn them into Characters with a Point To Make was not a moral calculus which would ever come out with me in the black.

I had gotten as far as an epigraph:

We are who we pretend to be, so we must be careful about who we pretend to be.

This was also a problem. In this one sentence, Kurt Vonnegut had elegantly expressed everything I’d hoped I might say in an entire book.

There were also roughly forty thousand words, written over two years, mostly useless, arranged into folders that I liked to move around. One day I dragged them over to the little trash icon and they disappeared with that noise meant to mimic crunching up paper.

The book was about secrets — the personal, complicated kind — about what constituted love, and what did not. But the secrets were not mine to tell. I thought a lot about their corrosive nature, and how so much could have been avoided if only people hadn’t kept secrets. But I could not resolve the conflict of a story that was not mine. So the secrets stay buried.

Sometimes I thought I imagined the voice of my father, who has been dead for ten years, imploring me to just not do this, please, though he would have never said “please.” I could tell you that for certain; what else he would say, I have no idea. My father was a complete stranger to me, even though I had known him for all of my life. The whole point of the book was that I might be able to find out who he was, if I could just uncover enough evidence, enough facts, stir enough ghosts.

My father was not a good man; he was what an objective reader might call a terrible person. This presents what is known as the unsympathetic lead. It also presents what will be familiar to all children of narcissists — a great deal of various awfulness that will haunt you in a seemingly unending number of ways for most of your life, until you decide that you are going to actively undo it.

My father stole people’s money, was prone to flights of unhinged fabrications — mostly concerning his self-professed genius — and frequently unleashed truly terrifying maelstroms of pure, animalistic, verbal rage. He meddled in other people’s affairs because he was bored and vindictive; when not doing this, he shut himself in a room during the day and slept for hours, then roamed the house all night. It was like living with a caged bear that was also responsible for ensuring your welfare, such as it was. By the end of his life at sixty-four he had alienated everybody he knew. He died alone and broke in a rooming house, and that is kind of poetic, but it’s also something that, when I think about it, makes me feel like a plastic container crumpled in on itself.

I spent my advance to get copies of his financials and academic transcripts and military records, which I tried to divine like runes, but which stubbornly refused to reveal intelligible patterns. I tracked down people from his past and somewhat traumatized them with the truth of his nature. I came to think that, in the amateur’s assessment, my father was quite possibly a sociopath: He was profoundly gifted at lying and charming and bilking others while, at home, he was a slovenly, profane, inexpressibly miserable figure of terror. Those two versions of himself never crossed paths with each other.

I traveled to Vietnam to try and retrace his steps at the Rex Hotel in Saigon, where he would have received his briefings to take back to the field. There’s a bar on the roof where the press would gather to do more drinking than reporting. I sat and looked over the city as giant Christmas lights were strung across a department store and carol snippets hung, disjointed, in the hot, thick air. It was hard to imagine how things would have looked back then, not least because what had been the so-certainly-threatening Communist scourge was obscured now by boutique, luxury shopping that felt like walking the streets of Soho. My father had never talked about this time in his life with me. He never really talked about any part of his life in an authentic way, but this part — the tail end of the first decade of the war — least of all.

I rode on the rickety bus to the sweating, dust-ridden Cu Chi tunnels where, after being given a sobering history of the war by an elderly Vietnamese man — who up until he had no choice except to fight, had been training in the seminary — tourists excitedly mounted the decommissioned tank and posed for photographs, brandishing the turret’s machine gun. I went further through the jungle to the firing range. When I pulled the trigger of an M16, I thought I was going to vomit. Next to the range is a gift shop staffed by people forced to listen to every deafening round being fired for ten hours a day. A heavily pregnant dog lied on the cold concrete floor of the shop; I patted her absently while drinking a couple of cans of one-dollar beer, one after another, to erase the sensation of the gun from my hands.

I puttered along the Mekong, lying in a hammock on the bow of a small boat for hours, until we arrived at a tiny fishing village at the end of a tiny estuary. At the village on the water, while the sun beat down on our necks and we dangled our feet in the river, we wordlessly ate charred, barely dead fish we folded into rice paper with cold noodles, fragrant, fresh mint and chopped chilis so hot I felt the heat on the outside of my face. Back in the dense, steaming city I daydreamed, briefly, of buying a motorcycle, abandoning the book I wasn’t writing, and living on cups of strong Vietnamese coffee and piping hot pho forever.

I kept thinking of what the book was about,: What it would say? What was its point? Why did it exist? People would ask me and I would say that it was about choices. Choices and their consequence. They would look at me like they didn’t understand.

The book would have been about power — power in institutions, of social structures. Of wars and who wielded them. Of personal agency and people with none. I thought that I could impose a structure of order upon chaotic personal histories and reckon things right. The book would have been about memory. How memory is porous, fallible, tensile, illusory. It would have been a book of fiction even if it were, in the reportorial sense, true.

I thought that the book might be about becoming, perhaps mine. I thought that if I looked hard enough into the past that something would be revealed. I thought it might have been a cleansing fire. But it wasn’t; it was a yoke. I had been seduced by the idea of being a writer, a writer of books. I imagined the book might advance my career, legitimize my tinkering. That isn’t a reason to write a book.

The book would have ended up on a shelf labelled Sad and Torturous Family Histories. Or, Read These Books and Feel Great About Your Own Parents! For a book that was meant to be about how these experiences did not come to define me, in the end, the process of explaining that had taken over almost all of my interior; it was like getting a flu shot only to come down with a bout so debilitating it put you in the hospital.

I lurked an email list I had been added to after my father died by someone who had served in his battalion. They would write to each other with news of their grandchildren’s graduations, and of commemorative group outings and increasingly of notices of those on the list who had died as well. There were barely any of them left alive now. I read their messages, keeping them all, for years. I was never quite able to invade their decades’ old web of careful connections, to disturb it, to dirty it up. So I watched as the years passed and their numbers thinned and their annual get-togethers grew increasingly more sedate. It was like witnessing a once mighty machine winding down. Where would my father ever have fit in to this? I didn’t have it, that sliver of ice.

We aren’t who we can’t pretend to be.

Elmo Keep is an Australian writer. She’s working on something else now.

History Revised

Now in a discovery reported by an international team in the journal Science, the new dinosaur species, Kulindadromeus zabaikalicus (KOO-lin-dah-DRO-mee-us ZAH-bike-kal-ik-kuss), suggests that feathers were all in the family. That’s because the newly unearthed 4.5-foot-long (1.5 meter) two-legged runner was an “ornithischian” beaked dinosaur, belonging to a group ancestrally distinct from past theropod discoveries.

So, says the study’s lead author, “[f]eathers are not a characteristic [just] of birds but of all dinosaurs.” The de-lizarding of dinosaurs has been a gradual humiliation, not just for the creatures themselves but for generations of children who lent them their most imaginative years. Now there are only feathers and teeth.

"Better and Worse Than You Thought It Was"

Awl pal Anne Helen Petersen on Harvey Levin’s empire of slime:

[I]t’s clear that Bieber’s tape was not the only near-priceless piece of dirt in the proverbial TMZ vault. (TMZ did not respond to multiple requests for comment.) According to these ex-employees, the sealed testimonies from the Michael Jackson molestation trial hide there as does footage of various celebrities — Bieber, Lohan, Travolta — behaving badly. The vault isn’t a secret at TMZ — even the lowest on the staff ladder have heard whispers of its existence. As to what goes up on the site and what stays vaulted, that’s a finer, more esoteric calculus — and one in which celebrities and their publicists have come to live in fear.

Also unsurprising: “Regarding the atmosphere of generalized sexism and discrimination described in the suit, male and female TMZ employees, none of whom were willing to go on the record, reported that it was all true, if not worse.” (See also: The Trials of ‘Entertainment Weekly’: One Magazine’s 24 Years of Corporate Torture.)

The Cathedral Ruins

by Susan Harlan

A cathedral is a good place to remember. I visited European cathedrals when I was too young to care about them. There was Chartres: buttresses and spires, relics lined up in rows in glass cases, a crypt that’s not filled with dead people, but is another church in the church. One of the tour guides told me that the cathedral’s nave was constructed on an angle so that medieval pilgrims’ muck could be washed right out the door; they would just toss buckets of water in there. She also said that people still walk out to the cathedral from Paris and that it takes three days. You leave the city behind for the country. “Paris,” she said. “Trop de monde.”

I was thirteen when I went to Notre Dame for the first time. It was so crowded that my family and I moved in a phalanx of tourists, our arms flat against our sides. The air smelled of sweat and candle wax. I dropped a coin in one of the little boxes and lit a candle and made a wish that I promptly forgot. The cathedral should have been significant, and part of me wanted to know more about the hunchback, but it was just a place of old things, and I was really biding my time until I could go to a sidewalk café and order a root beer float — glace vanille avec coca — and sit in Paris’ summer sun.

Now I remember these cathedrals refracted through another one. When I was in college, I found Saint John the Divine in Morningside Heights, which became my place in the city for about fifteen years. You go to some places and decide that you have seen them and that you don’t need to see them again; sometimes, you go to a place and you know that you need to see it again and again and again, like a person. I used to watch the peacocks strut in the cathedral’s gardens, and under the rosebushes, big rats slid along on their bellies. I watched the tour buses come and go, and the retirees walk in and out of the assisted living community across the street. Then I moved away, but ever since, whenever I visit New York, the cathedral is my aperture onto a city that keeps changing.

Construction on the Episcopal cathedral started in 1892, but there was never enough money to complete it, so it has remained unfinished. Inside, the stone is smooth in places but rough and raw in others, or stained with white watermarks and mold. There’s always scaffolding somewhere, proof of some kind of repair. The building is missing one of its towers on the northwest side. After a while, you get so used to it that the tower hardly seems to be missing at all, and this uneven façade seems both mournful and full of potential. It could be finished one day. It will never be finished. The soot on the stone outside marks it as a city cathedral. It looks a bit ravaged. Other places have restored themselves: Notre Dame began a major restoration and cleaning project in 1991. When I saw it as a teenager, I saw it in all its blackness, and I attributed its appearance to its medieval-ness. It was only when I got older that I realized that nothing could be more modern than pollution.

When I went back to St. John last February, it was raining. Inside, it smelled like mold and wet wool. As I stood in the nave, a woman who was looking up at the Rose window and walking at the same time accidentally backed into me. “I’m so sorry,” she said. Her hair was wet, like she’d been walking around without an umbrella. And I thought: if she forgot her umbrella, she probably lives close by, as I used to, maybe just up the street. I sat down in the Poet’s Corner to read. It’s really too dark to read there, but I’ve always liked the idea. When I was in college, the cathedral hosted a reading of Dante’s Inferno that ran from Good Friday through Easter Sunday. People took turns reading, and friends and I came and went over the three days, listening to bits of this poet midway through his life, being led on a guided tour through a house of horrors: people scratching their scabs; or steeped in excrement; or walking forward with heads twisted backwards. In graduate school, I brought my copy to the cathedral and read silently to myself and thought about how one goes about inventing hell.

I always go to one chapel in particular, the Chapel of Saint Columba, which was consecrated on April 27, 1911. The windows in the chapel are stained a silvery white, so the light feels cool in the summer, and there’s never anyone in this room, so I can sit down and stay there, sometimes for whole afternoons. Inside this chapel is a white gold altar by Keith Haring called “The Life of Christ.” Mary is in the middle, holding the baby Jesus, and the angels on the side panels are jumping for joy. This is a place of dead people: Haring made the altar just few weeks before he died. The chapel itself was a gift from a mother to her dead daughter, and the stained glass windows are also dedicated to the dead, their names listed on the walls. Inside the next small chapel stands an armored Saint Boniface, a looming stone figure with wings. And in others, men lie long buried in glossy white marble.

There are plans for a big residential tower on the north side of the property, right beyond my chapel’s windows. This tower will continue a development project that started with the completion of the Avalon tower on the southeast corner of the property in 2008. If you walk to the cathedral along Central Park North, you see this building. I went to the cathedral yesterday to see what else had changed. First, I walked back to the chapel and lied on the stone floor to look up at the mosaics on the ceiling. I could hear birds outside, behind the glass, in the direction of the phantom tower. Shakespeare called the monasteries dissolved under Henry VIII “Bare ruined choirs, where late the sweet birds sang.” There’s a painting on the chapel wall of Mary holding the baby Jesus in a ruined church. Vines and weeds grow all around them, and the gray stone walls crumble.

I wonder if St. John the Divine can be a ruin if it was never finished. Maybe finishing it will ruin it. This new tower will block the view of the cathedral as you walk along 113th Street, past St. Luke’s Hospital. There’s a construction site there that stretches back along the side of the building, a tunnel of blue plywood walls stamped with the phrase POST NO BILLS. Orange construction cones and a dumpster: all signs of what is to come. But there’s no one there. Just an empty weathered trailer, waiting.

Susan Harlan is an English professor who professes Shakespeare at Wake Forest University.

Photo by Ainhoa I

New York City, July 23, 2014

★★★ Garbage was invisibly in bloom on 3rd Street; a sanitation truck weaved from curb to curb, through the rot-laden air. The small patches of sun were already challenging. But the clouds were surprisingly good-looking, small and loose cumulus on clean blue, and they were even more surprisingly effective against the early sun. A man sat in the little fenced yard off Prince Street and watched the passing foot traffic, the sunbeam behind his amber sunglass lenses calling more attention to his gaze than if his eyes had been uncovered. Up on the roof, out of the air conditioning, the heat was therapeutic, the brightness overwhelming in a soothing way. The afternoon sidewalks were glazed with filth, the pale ornamented face of the Bayard Building drenched in light. Out on the open pavement, the heat was baking. The west seemed to be darkening. Clouds assumed more threatening configurations for a while, but the threat held off. Then, at bath time, it arrived, with thunder that sounded throughout the apartment and rain washing down the avenue. The lightning was strobe-intense, enough to briefly stun the eye. More high and distant flashes lit the clouds lavender. Sirens and the beeping of snarled traffic joined the rumbling. A bolt appeared reflected in the eastern face of the glass apartment tower, its jaggedness overlaid with ripples.