Memes and Misogynoir

by Laur M. Jackson

On April 7, 2012, a fire broke out at the Chateau Deville Apartments, a complex located in Oklahoma City, Oklahoma. Though no serious injuries were reported, one woman — in whose home the fire started — was treated for smoke inhalation and five units were damaged, displacing several families and depriving many more of electricity.

The story reported by NBC-affiliate KFOR-TV included a brief interview with resident Kimberly Wilkins, who ran for her life as the building as the building burned:

You probably know her better as Sweet Brown. Her closing line, “ain’t nobody got time for that,” is sure to ring a bell.

How is it that a witness to an alarming event — a fire or sexual assault — becomes one of America’s favorite punchlines, a catchphrase, that proliferates everyday vernacular so thoroughly as to make her testimony unrecognizable?

Many have used the phrase “digital blackface” to describe the odd and all-too-prevalent practice of white and non-Black people making anonymous claims to a Black identity through contemporary technological mediums such as social media. It often involves masquerading behind the Black face of a fictional profile picture. These attempts, while hilariously transparent, take advantage of the relative anonymity of the internet to perpetuate decontextualized stereotypes and project an image of Black people that fits the desire of anti-Black individuals.

It goes undocumented and unaddressed in most cases, though occasionally the people behind the blackface are unmasked. When musician, alleged feminist, and keen event planner Ani Defranco came under censure after revealing a former slave plantation as the locale for her Righteous Retreat, a workshop for creatives, fans flocked to the event’s Facebook page in support of the gathering (and to attack its detractors), including “LaQueeta Jones.”

LaQueeta Jones’ comments include gratuitous usage of grammatically incorrect African American Vernacular English (AAVE), an evocation of MLK, and the bulletproof phrase of authenticity, “as a black woman.” An altogether weak attempt at internet minstrelsy, it prompted a skeptical Facebook user, MF Addaway, to track the IP address of “LaQueeta Jones,” and bust the actual account holder, Mandi Harrington — a white woman who had posted earlier in support of Defranco.

But most similar ventriloquism goes unchecked. On Twitter lie countless handles featuring a Black person’s image, run by users who are most assuredly not Black. These accounts, which often include a “ghetto” name — the formula prefix “La+” is a favored trope — are riddled with poor attempts at Black vernacular, and feature stereotypes from the minstrel stage. Unlike Harrington, whose contained, time-sensitive purpose was only to legitimate her own stance by replicating it with a Black voice, these users perform recyclable — retweetable — acts of humor on a worldwide stage.

After Cleveland hero Charles Ramsey became the latest in Black-people-relating-serious-events-set-to-autotune last year, Slate’s Aisha Harris scrutinized the ease with which Black interviewees — such as Ramsey, such as Brown, such as Dodson — are subject to processes of memeification. Harris’ sense, as is mine, is that the phenomenon “has something to do with a persistent, if unconscious, desire to see black people perform,” and in so doing, reaffirm a simplistic idea of what Black people are. In their memeification, Dodson and Brown were stripped of context or any possibility that these individuals could be seen as human, and reconstructed as a caricature, as farce.

In the final evolution of the meme, the soundbite falls away and ventriloquism robs these individuals of the ownership of their own words. For a good while, I don’t think a week went by without the echo of “ain’t nobody got time for that” departing from the throat of some white suburbanite in my presence. So entrenched are Sweet Brown’s words in common vernacular — much like the many, many, many appropriated hallmarks of AAVE — this particular iteration of the meme appears to have a long shelf life ahead of it. (Fortunately, “Hide your kids / Hide your wife,” seems to have truly died.)

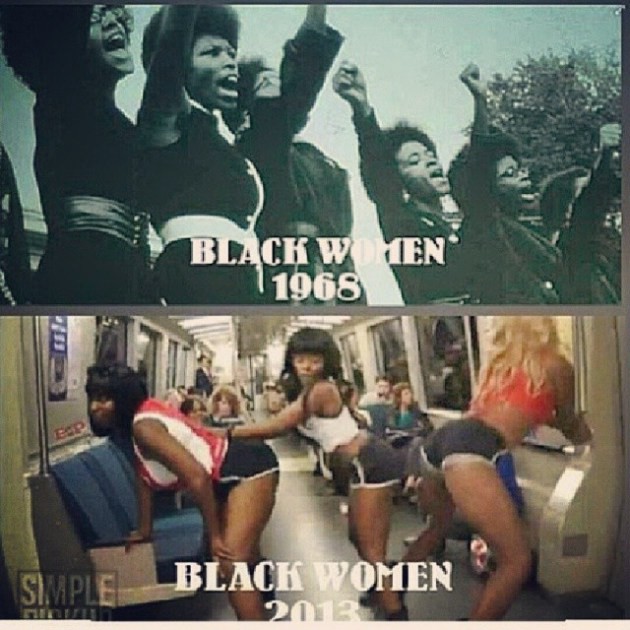

In Righteous Discontent, Evelyn Brooks Higginbotham coined the phrase “politics of respectability” to describe the an inventive method used by women of the Black Baptist Church during the Progressive Era to gain foothold in ongoing struggles for civil rights during the Progressive Era. Thereafter abridged to “respectability politics,” Higginbotham’s concept identifies racial progressive efforts whereby the “reform of individual behavior” is in fact the “a goal in itself” as well “as a strategy for reform.” The logic of respectability politics has since morphed into thus: If we look like master and talk like master, master will stop killing us and give us the rights we deserve. If we prove ourselves worthy of a humanity, they will see us as human. Chris Rock’s “Niggas vs. Black People” bit, which appeared his 1996 HBO special Bring the Pain still remains the often-cited proverbial example of respectability political rhetoric in action — though writers often fail to include Rock’s decision to retire the bit and his later acknowledgement of its dangerous implications amongst a mixed audience. (I prefer Don Lemon as the truly insidious modern example of this logic at work.) Unlike regular, old-fashioned anti-Black racism, respectability politics operates under the guise of progress and racial uplift. Those who find faith in its dogma love to bemoan the fate of a community who considers Beyoncé a role model, chastising us all with quotes and images of MLK and Maya Angelou, conveniently forgetting that they still shot King, and Maya Angelou had moves in her day that would give Queen B a run for her money.

Respectability politics are toxic and inherently anti-Black because they blame Black people for the racism they encounter. (For those who need a primer, Loryn C. Wilson at hoodfeminism sums up the major trademarks of respectability politics and why they suck.). Respectability politics place responsibility on already extra-vulnerable segments of the Black community and claim that the very existence of these people robs the entire community of deserved human rights. And while there are no shortage of lectures railing against sagging pants and expensive sneakers, and we’re still circulating the myth that more black men occupy prisons than university classrooms, a disproportionate portion of this responsibility falls on Black women; thus, respectability politics are not only anti-Black, they are also anti-Black women.

Scholar Moya Bailey of Crunk Feminist Collective invented the term “misogynoir” to succinctly describe the anti-Black misogynist intersection of racism and misogyny that uniquely impacts the lived experiences of Black women. More than just a combination of those two oppressive regimes, misogynoir lives in a realm apart from general-use sexism — which often acts as a placeholder for strictly white women’s experiences with misogyny — and anti-Black racism that targets Black men. Misogynoir acknowledges that while white women have been fighting for the chance to prove themselves in the workplace, Black women are considered the workhorse of both white and Black America. Misogynoir explains why an eight-year-old Academy Award nominee can be called a “cunt” with nary a peep from white feminists, while Lil Wayne’s reference to Emmett Till is considered out of line, and “Rich as Fuck” makes the mainstream airwaves.

Memes and misogynoir pair together like frat boys and public urination, Chicagoland interstate and gridlock traffic, and libertarians with that sour cottage cheese smell; familiarize yourself with the former and you will inevitably encounter the latter. Many, many, many, many memes coming from Black social media spaces display misgynoir from jump. They rarely involve any kind of clever wordplay — only recognizable meme-text over a vaguely related photograph. They represent, in every way, the basest in memeified humor.

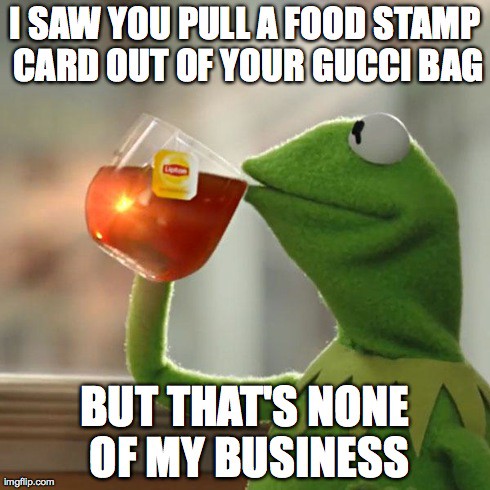

A lot of memes do originally derive their humor from good-natured sources. The recent #ButThatsNoneofMyBusiness meme — already nearly played out as I write this — began as a hilarious tribute to human pettiness. It features a photo of Kermit The Frog, pulled from Lipton’s 2014 #BeMoreTea campaign. In a reversal of Lipton’s attempt to make the imaginary experience of Kermit drinking tea resonate for real-life consumers, Black Twitter returned the character’s tea sipping back to the figurative — taking on its vernacular usage, as originally adapted by Black and brown queer communities (also “shade,” a word that in meme-like fashion has been watered down by non-queer, non-Black folks, to describe the weakest of reads). Early topics ranged from minor social contradictions to exaggerated fictional scenarios and passive aggressive divulgement of secrets. #ButThatsNoneofMyBusiness evinces beauty in subtlety — that linguistic concealment of intent, but not meaning, that Black folks have mastered as a manner of communication through centuries of enslavement and white supremacy.

As the meme ascended far past the ranks of social media obscurity (even Nicki Minaj joined the fun), frivolous grievances gave way to more sinister, more familiar tropes as the community’s favorite formula for identity-policing entered the mix. Social media proves itself over and again to be complicit in the structures that make vulnerable targets comedy’s most clutch resource; racism, transmisogyny/misogynoir, classism, ableism all pose weak barriers to a comic with dwindling material (or little talent) and participants in the meme’s circulation were not about run on empty. Unlike earlier versions of the meme, which called out bad behavior, these images lambasted those who are deemed incompatible with the wholesome picture of black respectability. The meme adopted poverty, fatness, sexual activity, government assistance, and lack of formal education as scorn-worthy topics to the response of likes, shares, and retweets from thousands. Ridicule of these markers all came together in mob pursuit of the “rachet” Black women. “Rachet,” a formally exclusive part of AAVE has of the past few years replaced “ghetto” in the anti-Black lexicon descended from Reagan’s “welfare queen,” a rhetorical myth created to leach sympathy away from Black mothers in poverty (and well, all Black people).

Black women almost exclusively bear the burden of respectability in Black social spaces online and therefore the burden of rachetness. She’s poor? She’s rachet. She has sex? She’s rachet. She has a child? She rachet. Had an abortion? Rachet. She’s a side chick and knows it? Rachet. Side chick and doesn’t know it? Rachet. Got a weave? Rachet. Has naps? Rachet. Likes to dance? Rachet. Still in high school? Rachet. Graduated high school and now works a job? Rachet. Graduated college and can’t find a job? Rachet.

We find these messages in the memes themselves. Pick a meme, any meme, conceived or co-opted by Black social media — I’ll show you a meme that worms its way toward respectability political rhetoric, with misogynoir at its core. Misogynoir is the fulcrum of anti-blackness in these memes. Take the “_____ be like” memes, which granted, were on shakier ground to begin with (we don’t need bell hooks to tell us why memes like “Niggas Be Like” or “Bitches Be Like” aren’t the most progressive). Much like #ButThatsNoneofMyBusiness, “_____ be like” takes hypocrisy as its main platform, calling out the contradiction in what people understand themselves to be and what occurs from others’ perspective.

Amidst the meme’s “battle of the sexes” potential, the meme bows to respectability politics and misogynoir as users take the fill-in-blank component as opportunity to rehash the anti-Black canon.

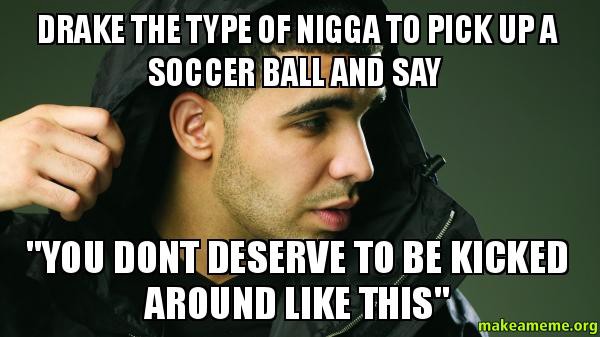

Tangential memes like “Drake be like” and “Drake the type of” take cues from the rapper’s penchant for soft beat ballads and fashion Drake into a hyperfeminized caricature. The humor derives from hypothetical Drake’s deviation from acceptable Black heteromasculinity. He treats women like friends and sisters instead of potential sex partners. He adds smilie faces to the end of his texts. He has feelings. A Black man who articulates his feelings — lol, right? The sensitive light-skin archetype appears plenty throughout meme culture, where light-skinned Black men in general are similarly memeified into inadequate pillars of manhood by virtue of an inherent lack of aggression and feminized displays of emotion. It is the misogynist and homophobic counterpart to hypermasculine and animalistic portrayals of dark-skinned individuals in memes. And it’s hardly a coincidence that the examples of memeified misogynoir throughout this piece also feature darker-skinned women.

What is the half-life of a meme? What is the rate at which a good-natured meme decays into the grossest displays public ridicule? How long until a Black feminist anthem falls prey to misgynoir’s messengers? Perhaps fault lies with the name, that the overlay of social media spectacle and

evolutionary principle

encourages us to speak of memes with a sentience external to ours.

But memeification requires participation, action, even innovation. The anti-blackness that finds refuge in memes really evinces the human existence behind the crudity of the image. And ease of sharing does not erase the responsibility of the person who chooses to do so (nor the harm this causes). Social media is not apart from the real; the internet is real-life. The misgynoir cultivated by memes manifests in the day-to-day lives of Black women who must persist in asserting their humanity within their own community. So I ask: Can we stop hating Black women?

Laur M. Jackson is a graduate student from Chicago.

The Most Correct Way to Grill Vegetables on a Stick

In a few days, grills will be ceremonially set ablaze for Labor Day (“it’s the end of summer,” we’ll say, even though the first three weeks of September are still summer, technically and temperamentally). Many of those grills will be piled high with vegetables. Good: Direct heat and smoke can do lovely things to plant matter. But the most common technique for grilling vegetables, the kebab, is performed incorrectly by the vast majority of American grillmasters of the universe — even though most other countries mastered the technique sometime around the time it was discovered that fire hurts when you touch it.

Stabbing things with a skewer and putting them over open flame is just about as primitive as it gets, and we still do it because it’s 1) a convenient way to grill bite-sized pieces of food 2) fun and 3) delicious. Pretty much every culture has independently invented some version of the kebab, whether it’s brochette or yakitori or pinchos or satay or döner. For some reason, we Americans have chosen to ignore all of these kebab styles in favor of just one: shish kebab, a mutant version of Turkish şiş kebab that is a fairly simple riff on skewered grilling. If one had to pick a single way to grill vegetables until the end of civilization, it’s not a bad choice at all, with dominant flavors of lemon, oregano, mint, and olive oil.

Except.

The typical American kebab consists of cubes of raw meat or fish or shrimp, marinated (or maybe not), shoved onto a skewer in an alternating pattern with raw vegetables like onion, bell pepper, zucchini, and mushroom. These kebabs are then grilled, badly. The problem is that each vegetable needs a different amount of cooking. A pepper benefits from a hard, quick char, but a mushroom takes awhile to cook; it needs low or indirect heat for a long time. Zucchini falls somewhere in the middle, best cooked at a medium amount of heat for a medium amount of time. Putting all of these items on the same skewer and expecting the same amount heat applied for the same amount of time to cook each of them properly is the equivalent of putting raw hamburger meat onto a bun and putting it in the toaster: By the time the burger is done, the bun will have crumbled into ash.

The solution, which many Americans refuse to acknowledge, is that each ingredient should get its own skewer. Literally everyone in the world who is not an American citizen does this when cooking skewers over an open flame: Your chicken-skin yakitori is not skewered with chicken thigh; your lamb shashlik is not skewered with mushrooms; your peanut-rubbed chicken satay is not skewered with mutton. So why is your dumb green bell pepper skewered with a cube of zucchini?

Grill each vegetable separately, then combine them on your plate. This will be sort of a bummer for those who love the one-skewer-per-guest model; an entire meal on a stick just rubs us the right way. I sympathize! An all-in-one kebab is like a corn dog delivered by an Amazon Prime drone. Just the thought of it arouses me. But it can be — and in this case, trust me, it is — worth it to make things a little bit less convenient in the interest of flavor and texture.

It can be fun to treat these like little mini-courses or tapas; “Hey guys, the mushrooms are ready! Next up, scallions!” “That sounds great, we love you, grill-master!” And they will love you, because cooking all these ingredients separately is more difficult from the grill-master’s perspective. You have more things to keep track of on your grill; you have to know how to cook each individual vegetable; and it may be very difficult to have all these vegetables finish at the same time. But a properly charred pepper, a delicately blistered tomato, a slow-roasted smoky mushroom — these are wonderful wonderful things that are worth the effort and lack of convenience. SEGREGATE YOUR SKEWERS, AMERICA.

But! This doesn’t mean that you can’t combine some ingredients; vegetables with similar cooking needs can be grouped together. Here are some of my favorite ways to grill skewered vegetables:

— Skewering beans or peas is weird but fun; charred sugar snap peas are incredibly good and will be very impressive to guests. Char them on high heat quickly, so they get just a little blistered, then top with a mixture of lime juice, fish sauce, chili paste, and brown sugar (this is good on pretty much any vegetable; just keep trying it to get the balance right. If it’s too sweet, add more lime and fish sauce; too sour, add more sugar) and crushed peanuts.

— A simpler one: take mushrooms (the traditional whole button or chopped portobello mushroom work fine, or even a mix); put them in a ziploc bag. Take a microplane and grate several cloves of garlic (more than you think you need) into the bag, along with some salt and olive oil. Seal, toss, and let sit for as long as possible, up to a day, before skewering and grilling.

— Marinate several kinds of cubed summer squash, which all require roughly the same amount of time on the grill (not exactly the same, but close enough if you avoid crook-neck squash), in a mixture of lemon juice, olive oil, and fresh thyme. This is a fun one because they’re all slightly different, in color and shape and texture, but can be grilled on the same skewer.

— Onions are a tricky one; I’ve never managed to cut an onion so that it stays together and grills evenly. Fuck it! Switch to scallions instead. You can pierce them right through the white bit, near the root, with a thin and sharp skewer. If you can, place the white part on a slightly higher heat than the green part. But the great thing about grilled scallions is that the green parts, when charred, are ABSURDLY DELICIOUS. You just want to make sure the white part is cooked enough to lose that raw onion flavor. Top with salt and pepper, or soy sauce and just a drop or two of sesame oil right before serving.

— How about fruit? Yeah! Grill some fruit! This is an opportunity to mixx it up a little, too: most kinds of stone fruit can be grilled together: cherries, plums, pluots, and apricots are my favorite, because ripe peaches/nectarines (did you know they’re the same fruit? True story.) are a little delicate for grilling. Serve with Greek yogurt sweetened with honey and some chopped mint or basil.

Skewered and grilled vegetables can be just as smoky and flavorful and ceremonial as any grilled meat. Or more! The sugars in vegetables can caramelize and the skins can char and crisp in ways that meats can’t, or shouldn’t. Grilling vegetables respectfully and carefully is a great way to celebrate the near end of summer produce before we move into fall. You can always have a burger in February, but the days when you can grill a perfectly ripe pattypan squash? Waning. Waning hard.

Crop Chef is a new column about the correct ways to prepare and consume plant matter, by Dan Nosowitz, a freelance human who lives in Brooklyn.

Photo by Joshua Bousel

This Week in Lines

by Jake Gallagher

10:04 am Tuesday, August 26th — La Colombe Torrefaction

Location: Church Street and Lispenard Street

Length: Eleven people

Weather: 75 and mostly sunny

Crowd: Late risers with enviable office hours

Mood: Pre-amped

Wait time: Six-to-eight minutes

Lingering question: if you’re getting your morning coffee after ten in the morning, what time do you have to be at your desk by?

6:09 pm Monday, August 25th — Diner en Blanc attendees waiting to cross the street

Location: Hudson Street and Moore Street

Length: Forty-seven on this corner, with hundreds more infiltrating the surrounding streets

Weather: 84 and mostly sunny

Crowd: White-garbed eaters of all ages moving collectively in a blanked out mass

Mood: Stark

Wait time: unknown

Lingering question: Why isn’t Tide to go sponsoring this event?

5:33 PM, Wednesday August 27th — Pre-Labor Day Weekend TSA security line

Location: Jet Blue terminal at JFK

Length: Twenty-nine people

Weather: 82 and partly cloudy

Crowd: A small slice of America at its most anxious

Mood: Exacerbated and ill-prepared

Wait time: Fifteen-to-twenty minutes

Lingering question: Can I keep my shoes on?

Jake Gallagher is a writer for A Continuous Lean and other places.

New York City, August 27, 2014

★★★ It was not hot yet on the way to nine in the morning, over wet, newly washed sidewalks. The air had gotten clearer overnight; the sky was a sharp blue. Cigarette smoke floated in the early light on 81st Street. The heat and haze came on, but with no power to chase people away. A group sat in the shade in the not-really public park with food, a stroller, a little dog in a harness. The tops of the honeylocusts in the sun were a green fluffy line going down the street. The clouds were blurry and discolored, even relatively high in the sky to the north. The warmth stayed in the streets after the direct sun was gone. Still, going up into it was more appealing than waiting on the hot platform for a 1 train for a forecast six minutes. A blinding shaft of light from the lower middle of One57 lit the faces of people sitting on benches on the Broadway median — three blocks up and more than a full crosstown block over — and went on to hit the sidewalk and building face on the west side of the street. Sewage smells came from someplace, or places. A light sweat came on, in proportion to the accumulated exertion of the walk. Bright orange spots appeared in the sky, maybe a half-dozen different possible cloud-screened suns. Then they resolved into a single thick pink streak.

A Poem by Debora Kuan

by Mark Bibbins, Editor

Mantra

My husband didn’t like his mantra.

“Shirim” or “Shring” or “Schwing,”

something to that effect.

My own mantra was much longer.

“It is only money.” I chanted

it in the shower. I whispered it

into a mussel. I shouted

it from the fire escape to

the ramheaded gargoyle

across the street. I think

you’re doing it wrong,

my husband said. Your eyes

should be closed and you

shouldn’t be shouting.

I ignored him and continued

my diatribe, shaking my fists

at greedy little ghosts.

You don’t control me, money!

No, you don’t! Then I went

inside and fried up a $50 bill

with sauerkraut and ate it

with a side of buttered toast.

It didn’t taste like chicken.

I’d say more like manta ray.

Debora Kuan is the author of Xing (Saturnalia Books, 2011). Recent poems and fiction have appeared in Adult, Brooklyn Rail, Buenos Aires Review, The Iowa Review, and HTMLGIANT. She has been awarded residencies at Yaddo and MacDowell, has written for Artforum and Art in America, and is a senior editor at Brooklyn Arts Press.

You will find more poems here. You may contact the editor at poems@theawl.com.

An Awl Programming Note

by The Awl

Do not adjust your feeds; they are working correctly. Rather than let pieces trickle out over the next couple of days while we sit by a pool or alone on a mountaintop and try to pretend that our lives, like the summer, are not rapidly collapsing into a single point of nothingness, we are trying an experiment in which we publish all of the day’s stories at once. If it proves successful, we may consider an entirely new form of publishing, in which we bundle an entire day’s worth of news and commentary into a single package that we deliver to your doorstep. It has never been done before. We’re not sure what we are going to call it, but the sound of “hyperlapse publishing” has been bouncing around the office, and it has a nice ring to it.

Every Sylvester Stallone Character Name That Is a Noun or Verb

by Joe Berkowitz

17. Jack Carter

16. Robert Hatch

15. Henry “Razor” Sharp

14. Kit Latura

13. Stud

12. Robert Rath

11. Rocky Balboa

10. Joseph Dredd

09. Gabe Walker

08. John Spartan

07. Jerry Savage

06. Ray Tango

05. Weaver

04. Cosmo Carboni

03. Lincoln Hawk

02. Angelo “Snaps” Provolone*

01. Ray Quick

*This name also bears the distinction of being a complete sentence