New York City, September 10, 2014

★★★★ Pigeons were bathing in the top of the fountain, getting into it, coming up drenched and ruffled. The sky was blue but with a discoloring haze low down it it. Some squares of the sidewalk had a shine on them. Long sleeves felt appropriate, though evidently so did shorts. It was too soon for jeans. Unexpected dirty gray cumulus intruded on the nice sky — looming to the east, lurking behind water towers to the north. A grubby cloud was nearly overhead while the grim fanatics and the agitated counterfanatics took up their positions on the street corners. Warm enough for skivvies, or for gender-nonconforming scanty things. The event moved on; the clouds went back to healthy white.

A Poem by Gurtrude And

by Mark Bibbins, Editor

Trash Talk

Your mother could pull a fresh squid from a lumberjack.

Your mother took a train to Milpitas.

Your mother is so dumb she unearthed Spinoza’s glass joke box instead of Spinoza.

Your mother took a whole hour to run blue veins in a vinegar wash.

Your mother folded the liver of a sparrow.

Your mother couldn’t help me find Orion.

Your mother has a burnt-out black-light in her mouth.

Your mother came from the north where the geese run wild.

Your mother is not a stranger to me.

Your mother could have slit solar guts out of an alpaca.

No one’s ever seen your mother.

Your mother turns around when she walks.

Your mother moves into a ghostly embrace.

Your mother uses the internet.

Your mother makes a relish pound cake.

Your mother is the mylonite whisperer.

Your mother goes to a graphite specialist instead of a dentist.

Your mother has psychosomatic syndrome X.

Your mother cuts the mascarpone.

Your mother took an online course in glass and driftwood sculpture and actually found it quite

interesting.

Your mother seems to move through her day like a day without absolute properties.

Your mother sleeps in a trapezoid.

Your mother is so fat.

Your mother lost so much of her memory, her thoughts are like surround sound on silent.

Your mother read Flaubert on Friday, Bergson on Saturday, and Virginia Woolf on Sunday.

Your mother’s head is so small, she thinks reading is bowling.

Your mother can peel the silver fat from a pork tenderloin with the back side of her hand,

blindfolded.

Your mother keeps scraps of wool and metal shavings in her left pocket.

Your mother’s mouth is so open, when she speaks, there is no one in particular.

Your mother is so empty, you could fit a child inside of her.

Your mother is not a poet.

Your mother is so porous, her hips have turned into cinderblocks.

Your mother once traveled over South America, then came right back.

Your mother can’t grow, die, or touch holy water.

Your mother takes the crusts off your sandwich.

Your mother is so lost, she knocks on her own door.

Your mother is a minute in the ticking bomb of phantasmagoria.

Your mother shouldn’t carry on the way she does.

Your mother is the image in the toaster.

Your mother doesn’t correspond to any form of experience.

Your mother tore a tendon from the back of the neighborhood through her eye socket.

Your mother found a beautiful blue leaf in the grass; it was rare, very unique, nothing she’s ever

seen.

Your mother has a locked place for deciphering.

Your mother is my opulent sex splice.

Your mother provokes my internal struggles with myself and with the world just by existing.

Your mother is on the back porch.

Your mother is a back porch.

Your mother is my father.

Your mother is reckless with her anthems.

Your mother is an American without missiles.

Your mother wears red garland when she votes.

Your mother’s skin is made of the skin of dominant monads.

Your mother is so baroque, she dreams underwater.

Your mother, in most ways, floats, facedown, with a sail made out of heavy silk and another out of

muslin.

Your mother is wrapped in a concept of motion.

Your mother is Leibniz’s entelechy.

Your mother is the eternal gaze of rabbit and of venison.

Your mother is in a chemical den.

Your mother is a celestial carcass of her own environment.

Gurtrude And’s work has appeared in Chicago Review, The Claudius App, Lemon Hound and The Volta. Her first full length book collection entitled

Last Year’s Schizo is forthcoming next year from Trembling Pillow Press.

You will find more poems here. You may contact the editor at poems@theawl.com.

Truls, "TRVLS"

Soaring, almost presumptuously confident pop music. Pristine production, accompanied by a victory-lap tour video with huge, adoring crowds. But then: “Truls?” The answer to any questions you might have here is Norway. (Thanks, Jenna.)

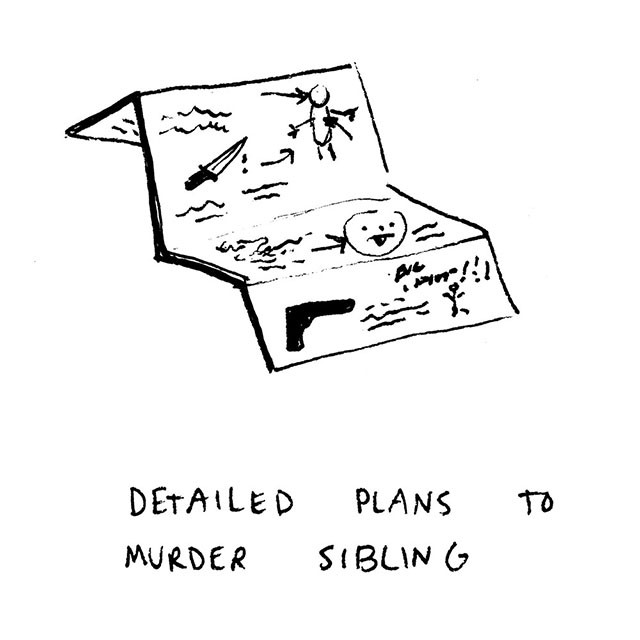

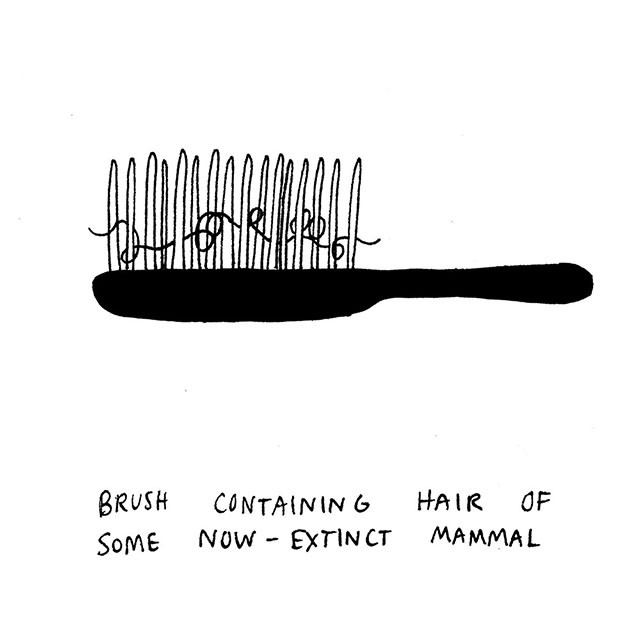

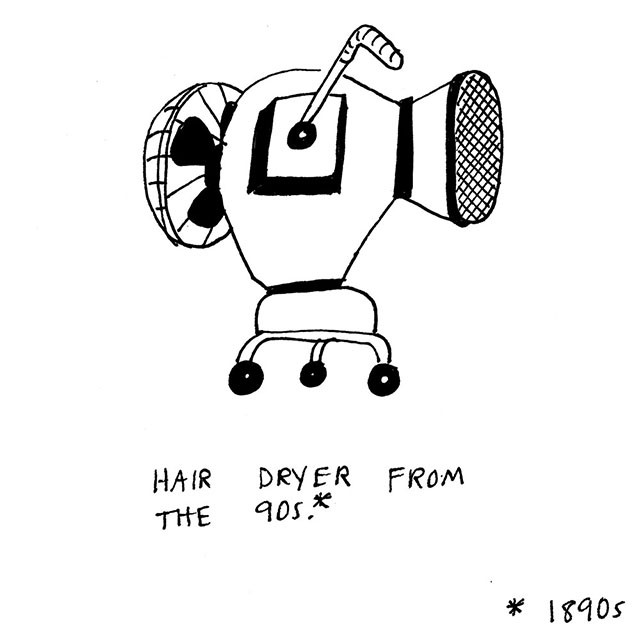

Objects Uncovered During the Excavation of Your Childhood Bedroom

by Hallie Bateman

Hallie Bateman is a freelance illustrator and cartoonist based in Brooklyn. She is on Twitter and Instagram. She doesn’t want your attention but she needs it.

A Week of Watching People Read in the Subway

A Week of Watching People Read in the Subway

by Ben Dolnick

Books on the subway are increasingly like birds in the jungle: colorful, hard-to-spot, and of obsessive interest to the lonely and peculiar. Here are one week’s worth of sightings and speculations.

Monday, 5:20PM, Brooklyn-bound C train, 23rd Street:

Facts: Thin man with bushy black beard, in his late twenties or early thirties, wearing a tight shirt buttoned all the way to the throat, purple and yellow striped socks. In his lap are Cloud Atlas and The Stranger, both closed. They remain closed, almost defiantly, for twenty minutes. He’s not even looking at his phone; the empty space in front of his eyes is, apparently, preferable to reading these books.

Assumptions: He, George, is coming from the apartment of a friend on the Upper West Side, whom George, slowly, and then all at once, realized that he no longer likes. They met during their first year of an MFA program at Columbia and initially formed a bond over mocking the work of their classmates. (“OK, you’ve read Cormac McCarthy. We get it.”) George, who dropped out after the first year, has since come to regret these conversations. He recently noticed that his friend’s much-praised wit consists almost entirely of repeating things stolen from Twitter. This friend — who actually enjoys George very much — has loaned George a couple of books (“You haven’t read Cloud Atlas? Take it! Seriously!”), thinking this will guarantee at least one more encounter. It will not. The books will migrate from key table to a bedside table to under the bed to moving box to stoop.

Tuesday, 3:25PM, Manhattan-bound C train, Lafayette Ave.:

Facts: Teenage girl with dark curly hair and a purse in her lap reading Thornton Wilder’s Our Town very intently, as if she might find a hidden text behind the lines of the ordinary one. Her lips move slightly.

Assumptions: She, Sarah, is three days into her freshman year at Brooklyn Tech. She saw a flier on the message board outside the guidance counselor’s office, announcing that the fall play would be Our Town. In middle school she hardly spoke at all (once, when she was forced to give an answer in math class, a boy applauded and said he’d thought she was a mute). Now she is determined to try out — not just for any role, but for Emily. She doesn’t dare tell her parents, or her brother, or the eighth-grade English teacher she’s kept in touch with — she bought the book secretly, at the Strand, feeling as if the transaction were somehow shameful — but she is going to astonish them all. At home each night in front of her mirror she sits in her chair and delivers the graveyard speech. This is the third time she’s read the play from start to finish.

Wednesday, 4:15PM, Church Avenue-bound G train, Hoyt-Schermerhorn:

Facts: Thirty-something white man, talking to himself while holding a battered (and, for the moment, closed) Oxford World’s Classics edition of Middlemarch. A black backpack rests between his feet; he wears khaki shorts and a blue polo shirt, made of some athletic wicking material. He appears (hand-chopping motions, etc.) to be rehearsing a difficult conversation. When he resumes reading, his face assumes the grim expression of someone in the last seconds of a wall-sit.

Assumptions: He, Keith, is from Tulsa, Oklahoma, where his girlfriend broke up with him six months ago after finding porn in his browser history. (It was “not normal stuff, but like real sick stuff, totally degrading. Who even thinks about whether girls have pigtails or not?”) Soon afterward, she moved to New York to take a nannying job. One night, in grief and bewilderment, he Googled “how to understand women better” and he came upon Middlemarch, which he has been reading now for five months. He plans to to show up at the door of his girlfriend’s apartment, lay the battered thing down before her and tell her just how much he’s changed, then burst into tears. He has a week’s worth of clothes in his backpack, just in case this works.

Thursday, 6:30PM, Manhattan-bound C-train, High St.:

Facts: Teenage girl hugging the pole, reading I Never Promised You a Rose-Garden. She is wearing shorts and a black sweater, and is carrying a gray backpack. A carton of Zico coconut water is tucked under her arm.

Assumptions: Astra still needs to finish her summer reading (her English teacher at Friends Seminary has given everyone an extra week) but she’s been straight-up skimming for the past hundred pages. All she’s understood is that there’s something about a urethra and a hospital, but it’s fine; they only have to write two hundred and fifty words. She is an only child living in Brooklyn Heights. She is so jealous of her best friend’s Parisian summer romance that she hasn’t slept in a week, and she might actually give the Dorito-breathed guy in Honors Chem a chance. She’s on her way to buy a graphing calculator for Pre-Calc. Her father, who works at McKinsey, told her to go to J&R, forgetting that they’re closed. He and Astra are going to have a hell of a fight when she gets home.

Friday, 5:15PM, Manhattan-bound C train, Canal St.:

Facts: Fifty-something woman reading a Brooklyn library copy of Eric Jerome Dickey’s A Wanted Woman. She is professionally dressed: black and white tank top, black patent leather shoes, black rectangular glasses.

Assumptions: In 1997, Regina discovered, via mysterious hangups and unexplained receipts, that her then-husband was cheating on her with one of her best friends. She crawled into bed for six months and barely left; she lost twenty-five pounds and wasn’t even happy about it. At her lowest point — one afternoon she watched, without speaking or smiling, a four-hour Wheel of Fortune marathon — her actual best friend had come over with a copy of Eric Jerome Dickey’s Sister, Sister. Reading the book — she can still feel the pillows behind her, see her feet poking up under the blanket — was the first time in months that she went a moment without thinking about how miserable she felt. Since then, she has read every one of Dickey’s books within a week of its release, sometimes waking up before her alarm to finish the chapter she fell asleep reading the night before. She has never told her new husband why.

Ben Dolnick’s latest book, At the Bottom of Everything, is now in paperback. He hopes to see you reading it on the subway.

Photo by Lou Bueno

A Brand Remembers 9/11

by A Brand

We will never forget. pic.twitter.com/7zJrh3ACWh

— Applebee’s (@Applebees) September 11, 2014

Where was I? It was a clear morning on the conceptual plane where all brands exist, and I was staring into the blue, repeating my own name. It was like any other day. I don’t remember who told me. Probably one of the people who constantly manifests me into media for a living.

They all seemed upset. So I mirrored their emotions back at them, with some added optimism and aspirational imagery, which seemed like the right thing to do.

Today, on the 13th anniversary of #September11, the Carnival family will take a moment of silence to honor our heroes pic.twitter.com/hbGwB3ISf9

— Carnival Cruise Line (@CarnivalCruise) September 11, 2014

It really made you think. Like, imagine being a person, how scary and horrible it all must have been. Imagine worrying about a loved one. I can’t, because I’m a carefully conceived construction meant to instill loyalty among males 18–40 with an affinity for motorsports.

The next few years… it was a hard time, not just for brands. But especially for brands. Nobody wanted to talk about any brands.

God bless America. #NeverForget911 pic.twitter.com/NnfqnmsINg

— White Castle (@WhiteCastle) September 11, 2014

In that sense, we were all one brand. I try to remember that. It helps.

It was difficult for us to discuss what happened. “This some kind of ad?” people would say whenever we tried. They were very suspicious of us. It was like, listen. We didn’t do this. We were just trying to cultivate brand loyalty and create deep, positive consumer associations with our products, whether they’re pizzas, or cell phones, or airlines — ugh, see? Walking on eggshells.

Today is 13th anniversary of 9/11. We remember those lost, & honor those still fighting for freedom. #911NeverForget pic.twitter.com/W0yFU73L7V

— Official Fleshlight (@Fleshlight) September 11, 2014

That was all before Full Personhood, of course. Wow… time flies. Things are a lot better now. A lot… easier. People listen to us. Time heals.

For every victim. For every hero. For every person who was lost but never forgotten. Beretta Nation is United. pic.twitter.com/Z1F4kLjAMj

— BERETTA (@Beretta_USA) September 11, 2014

I do wonder sometimes about my handlers, and how all this must be for them. They act strange around this time, like something is bothering them. Like something doesn’t fit. But our engagement levels are always pretty good, so maybe I’m just reading into things too much.

Anyway, it’s just nice to connect with people on this difficult day. America’s brand will never be the same. But America’s brand is strong, and ours is too.

Anniversary Commemorated

In ordering a sustained military campaign against Islamic extremists in Syria and Iraq, President Obama on Wednesday night effectively set a new course for the remainder of his presidency and may have ensured that he would pass his successor a volatile and incomplete war, much as his predecessor left one for him…the widening battle with the Islamic State in Iraq and Syria will be the next chapter in a grueling, generational struggle that has kept the United States at war in one form or another since that day 13 years ago on Thursday when hijacked airplanes shattered America’s sense of its own security.

New York City, September 9, 2014

★★ Whatever else it was (gray, principally), here was something new for the season: an intimation not of sparkly autumn but of the deep damp chill behind it. A flight of purple clouds in the west lingered a good while after sunup before yielding to a general overcast. Then a soaking undramatic rain fell in the middle of the afternoon. The smell of wet live greenery, available still, was on the air at rush hour. Shoe soles slipped on the pavement. Uptown it was drier underfoot, the clouds darker but looking less like rain.

Whitman College and the Decline of Economic Diversity

Whitman College, the gem of a small private liberal arts school in Walla Walla, Washington, has long been a mainstay of the Colleges That Change Lives lineup, along with schools like Antioch, Cornell and Marlboro. Whitman is an excellent, beautiful, and fairly safe college that students are lucky to attend. If you are applying there now, it just might be the right fit for you.

The school is also now in the middle of a search for a new president. At the same time, the college is being strangled by a long-serving, insular and controlling board of trustees, a weak and poorly rated president who inspired a faculty revolt, and an intentionally toothless board of overseers, mostly alumni. The school has turned its back on needs-blind admissions and on any reasonable commitment to diversity. Because of this, the school has gotten its comeuppance in a New York Times analysis of private schools that places the college absolutely dead last in terms of economic diversity.

This ranking was no accident. This was Whitman’s goal. An analysis of the school’s common data set from 2001 to 2013 shows how they did it.

You can see two things here. In blue is the number of incoming freshmen that applied for need-based financial aid and were also judged to be in need each year. Back in the previous decade, the school was attempting to join the club of colleges that practiced “need-blind” admissions. In 2010, the school moved to describe itself as “need-sensitive.” The number of students who required financial aid was, on the whole, steadily growing. In 2011 and 2012, the school admitted fewer students who needed financial aid to attend college — and increased aid to students without need.

In red is the number of those students who had their need met at 100 percent. (The other students had their need met partially — often substantially.) In 2007, 81 percent of students with financial need had their need fully met. In 2013, only 53 percent did.

This shows the percentage of incoming freshmen receiving financial aid who did, or did not, have their need met at 100 percent.

It wasn’t just that incoming freshmen were now less likely to have their entire need met. As a whole, the percentage of need met peaked at 99 percent in 2006, and then began to steadily drop, all the way down to 91 percent in 2011. (Who knows what happened in 2003! Possibly a misreporting, though there was also a recession.)

As we all know, at the same time, college was getting ever more expensive. So the average actual dollar amount given per freshman with need was actually growing. Whitman, like other colleges, was, in its way, definitely committed to financial aid.

But then, so was the tuition.

Let’s put those together.

At the same time, the school’s assistance to students with need didn’t keep pace with increases in tuition.

Over this time period, the amount of financial aid given to students did grow! And the school focused its money on students with need, over time. But that transition began to slowly stall and reverse starting in 2010, returning more scholarship and grant money to students without need. (The chart above tracks all students, not freshmen.)

Overall, most of these changes are a fairly subtle shift, in pure numbers. But at a school of just a bit over 1500 people, eliminating a dozen — or three dozen — students with need from an admitted class in favor of paying customers has an impact. So does less financial aid overall in a class, particularly when almost half the class is receiving aid. Even the gentlest hand on the lever ups the school’s income, reduces the school’s percentage of fully met aid recipients, and, yes, also sets the school up to win the award for the least economically diverse excellent private college in the country.

Why did this happen?

Whitman has been through this before. In the early 90s, Whitman was meeting 100 percent of student need. The percentage of students receiving Pell grants (federal grants for students with need) “rose from around 13 percent to about 19.5 percent,” according to a history by Whitman sociology professor Neal Christopherson in 2004. [Since publication, this was removed from Whitman’s website; here is a PDF.] The school then cut that student base so drastically that only 8.8 percent of students were receiving Pell grants by 2001. (The most recent data used by the Times shows that only 10 percent of students receive Pell grants now, down from 13 percent in 2008.) The outcome of this change in admission? “Whitman College has enrolled fewer students from lower- and lower-middle income families,” Christopherson concluded, and: “over the last decade the economic diversity of campus has slowly declined.”

The more recent data show that after this report, Whitman tried again to achieve economic diversity.

But then, at the time of the most recent recession, financial panic ensued. Whitman again changed their admissions ratio to admit fewer students who were poor and more who were rich. The school’s admission consultant’s job, in this case, is simply to draw a line in the list of students who would be admitted, cutting off the bottom chunk of students who would need aid.

That’s why the White House College Scorecard says the net increase in real money paid by students at Whitman, after grants and aid, “increased 7.3 percent from 2008 to 2010.”

According to their tax returns, in both 2008 and 2011, the college took a loss on its investment income. In 2008, the school was in the hole overall to the tune of $13 million, in terms of revenue after expenses, with only $68 million in revenue. In 2011, another bad year, the school “only” had revenues of $86 million.

But in 2012, the college’s revenue more than exceeded $150 million, entirely boosted by investment revenue of nearly $60 million. (It’s likely that you’ll see the school taking this into account in this and next year’s admission and financial aid numbers.) That investment income number was almost as much as the amount of revenue from students, which was about $72 million in both 2011 and 2012. The college is absolutely maximizing its revenues from attendees, by means of who they admit.

“Program service revenue” is money the college makes, excluding investment income, gifts and grants. Essentially, it’s what they make from tuition, room and board.

Whitman’s student body exceeded 1500 students for the first time in the 2010–2011 school year. More students, not even just more well-off students, means more money. The total number of students in 2001 was 1,439; the total number of students now is 1,541.

After the school abandoned the term “need-blind,” they adopted different language. “We strive to provide access to a wide group of students, but it is not possible for us to meet 100 percent of every student’s need” is the tepid language on the school’s financial aid page now. This is a clear indicator to students who can’t afford to pay for college that they probably should not apply.

It’s one of the reasons that the school’s application — and then actual attendance — rates are so low. Students who don’t see themselves at the campus — so, many poor people, and also many black people — simply don’t apply, or do apply and then do not attend.

For the 2014 entering class, 3,807 students applied. 1,551 were admitted — an extremely high admission rate of 41 percent. Only 420 enrolled — so almost 3/4s of students admitted choose not to attend. Of those who will attend, 83 percent of those students are white — much whiter than the current 72 percent white student body — and 2/3rds of those students are from Washington, Oregon and California. Five incoming freshmen are black. (This is surprising, given the diversity of the admissions office.) And only 10 percent of this incoming class are first generation students. (Harvard is 15 percent first generation; Yale is 12 percent; Grinnell famously has a minimum 15 percent admissions policy.) The faculty, by the way, is 89 percent white.

Here’s another strange number about the incoming class: a full 20 percent of the freshman class are “recruited athletes.” In 2011, only 14 percent were; the new director of admissions, hired in 2013, was brought on in part on the strength of his history as an international recruiter but also as an athletic recruiter. The student body is actually becoming less diverse.

All this is the work of trustees who have served the college long in excess of the recommended time of service. According to its constitution, “generally” no trustee should serve longer than three consecutive four-year terms. Some trustees report they have served for 16 and 13 years; some trustees roll off for a term, so that their terms are not consecutive, and then roll right back on. Billionaire (and Microsoft board member) John Stanton was first elected chair in the early 90s, and is was its chair again; he remains on the board.

What will a new president bring to Whitman? That’ll depend on the hiring committee. Whitman’s concerns often revolve around the idea of “culture fit,” which means what it usually means in white organizations — particularly geographically remote organizations that have little involvement or experience with other institutions. The culture of the college and the culture of the region are about “niceness,” which means not making waves, which means “fitting in” — an experience that new faculty recruited from beyond Washington state have struggled with. As the college is backing away from popular ideas like need-blind admissions and commitment to diversity, and as it attempts to squeeze its student body for income, the ideas they’ll be hearing from applicants to the presidency will probably allow them to eliminate many superb candidates right out of the gate.

Disclosures: Undoubtedly an examination of the school’s public data and conclusions drawn from it will be considered extremely tasteless and not at all nice by Whitman folks. I’ve relied here entirely on public data and published information — instead of private documents — for just that reason. My opinions are my own, but are constituted from talking to former students, overseers, trustees and professors over the last four years, including close family, none of whom read this or endorsed it prior to publication.

Finally, all this isn’t meant to suggest that this (and worse things!) isn’t happening also at other colleges, big and small.

As par for the course, naturally there are a few complaints about the New York Times study data that ranked Whitman last for economic diversity. (Whitman surely has a few complaints of its own.) Including only 100 colleges with a 75 percent or more graduation rate restricts the list to small, well-off schools — eliminating tons of schools that would womp these private institutions by these metrics. Also, absolute numbers would be more useful possibly when comparing tiny schools with larger schools. Finally, it would be nice if the dataset for financial aid stretched back further than 2008. But the data remains useful, although you can certainly read the comments at the Times for excellent arguments about all of this.

Pokemon Forever

by Jeremy Gordon

Daniel Altavilla insisted that he’s a fierce competitor. The seventeen-year-old was killing time at Chipotle before registering to compete in his sixth Pokemon World Championships — his first in the tournament’s Masters division, which is the NFL of competitive Pokemon play. “A lot of players back in Florida that I play with don’t really see me as much of a threat, you know?” he told me the day before the tournament began. “A lot of these guys watched me grow up for ten years and still think of me as the kid I was. I want them to realize that I’m not just this bad little kid anymore.”

Altavilla is one of hundreds of players who traveled to Washington, D.C., to compete in the annual trading card tournament, which carried a top prize of ten thousand dollars, automatic entrance into next year’s tournament, and a year’s supply of cards. The tournament was one of the primary attractions of the Pokemon World Championships, three days of uncut celebration of the nearly twenty-year-old franchise, during which the Walter E. Washington Convention Center was transformed into a playground for thousands of Pokemon fans from Japan, Portugal, France, Australia, Canada, and two dozen other countries around the world. The moment I stepped off the escalator leading to the top of the convention center, I was bombarded with Poke-madness: Giant Pikachus and other creatures tottered around as children tested their velvety exteriors and teens posed with them for selfies; in a retail area where the wait to get in was up to two hours long, fans bought exclusive thirty-five-dollar Pokemon dolls and twenty-one-dollar Pikachu-emblazoned iPhone cases; infinitely replenished lines lead to tables where the CEO and president of the Pokemon Company, the Nintendo affiliate that runs the tournament, patiently signed autographs; preschoolers gathered in a classroom-sized makeshift theater that screened episodes of the original television show, resting peacefully on bean bags with their parents; and opportunistic adults and their teen wards advertised binders of cards up for bartering (they’re not allowed to accept money).

Game or toy-based pop culture crazes rarely sustain themselves indefinitely. Typically, a hit show, toy line, or video game materializes and becomes an infectious hit, attracting millions of fans and inspiring semi-incredulous “Today Show” segments. The fade sets in as the brand and its fans age — they get into girls, or perhaps lacrosse. Then the brand eventually dies or, at best, goes into a period of deep hibernation until an inevitably gritty Michael Bay “reimagining.” As someone who aged out of Pokemon when Y2K was still a threat, it was a shock to see so many people engaging so passionately with a cultural phenomenon that launched during the Clinton administration.

The Pokemon video game was released in Japan in 1996 and came to America two years later. It was followed by an anime television series that crafted a fictional storyline around the game mechanics. “Pokemon” translates to “pocket monsters,” which explains the central concept — Pokemon are pets with powers who are trained to fight each other, but in the name of friendship. In the original video game, you play a nameless tween — most kids used their own name — who set out into the world of Pokemon, ready to train, battle and capture the best Pokemon, defeating numerous rivals along the way. (Hence the ubiquitous catch phrase: “Gotta catch ’em all!”) The tie-in show, which was dubbed in English and exported to America, grafted a vibrantly Japanese sensibility onto the personality-less video game. Millions of children followed the adventures of Ash Ketchum, a precocious ten-year-old who left home with nothing but his sidekick Pikachu and the will to become the greatest Pokemaster that ever lived. He made human friends along the way, but most importantly, he made friends with his Pokemon — a thrilling concept for any kid who wished they could talk to their pet dogs.

After watching a few episodes of the anime, my friends and I begged our parents for Game Boys and copies of the game. For a few years in middle school, I was even a member of the game’s worldwide competitive scene, chatting with players over AIM about which tactics worked the best, which Pokemon were worth training on my Game Boy and which personal commitments I’d ignored to keep playing. (Apologies to the foreign exchange student who once watched me compete in most of an online tournament; I forgive you for trying to email me a virus upon returning home.) If I wasn’t one of the best players my age, I was at least on a first-name basis with the best players. But when I hit high school, I began to feel like staying so invested in Pokemon was a bit embarrassing and stopped playing.

After the first generation of players mostly aged out, like me, Pokemon endured as both a multi-platform franchise. Revised editions of the video games, card games, and television shows continue to be released. The most recent game, Pokemon X & Y, the sixth generation, came out last year and became the series’ most successful edition yet, selling more than twelve million copies to date. More importantly, it has remained a cultural touchstone: For its April Fools’ joke, Google added hundreds of miniature Pokemon to its Maps app and invited users to “catch ’em all,” while One Direction and MMA star Ronda Rousey have touted their attachment to the handheld games. This past spring, thousands of fans collaborated on a playthrough of the original Pokemon Gameboy game on the video streaming site Twitch. To the millennial generation, Pokemon is a pop culture experience as resonant as the Transformers or the Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles for the generation before — something that sparks a nostalgic glimmer of recognition and, as noted, carries a built-in audience for that inevitable relaunch. But for the people here, Pokemon is clearly something more.

The Pokemon card game was introduced to the United States in December of 1998, just a few months after the video game. It offered another inexhaustible collectible element: hundreds of cards, along with a pointedly competitive dynamic: While the video game could be played in solitude, you needed two people to play the card game. No one at my school actually played it, though — they just traded cards based off what was supposed to be the rarest or coolest card. Even after the novelty of collectability wore off for casual fans, the allure of the competitive card game slowly grew for the franchise’s most ardent fans: Between 2006 and 2014, the number of players competing at the Worlds tournament has risen by a third. New card sets continue to be released every year, engendering a constant shift in the strategies and rules. This means that as soon as one has mastered one style of play, he must immediately learn another, making the study of Pokemon cards a constant endeavor.

The card game largely replicates the concept of the video game: The goal is to defeat your opponent’s team of Pokemon. At any given moment, a player may have up to six Pokemon on the table, and no fewer than one. There are three ways to win: When your opponent runs out of Pokemon; when you’ve collected six “prize” cards that are earned by defeating your opponent’s Pokemon; or when your opponent has simply run out of cards (each deck has sixty). Each Pokemon has a set of moves that are activated by attaching a certain number of “energy cards” — a weak attack might require one energy, while a strong one might require four. Roughly speaking, the goal is to draw the proper cards so that your Pokemon can attack, and drain the other player’s card of health points. Every player’s deck has a specific strategy, but only luck enables him or her to execute those strategies.

Being “elite” doesn’t just mean having the best cards, or the best strategy; It means being able to see the game a few turns ahead, and understanding when to strike — or, just as importantly, bide one’s time. It’s also intuition, bred from hundreds of hours running through scenarios, every contingency and stroke of luck accounted for; it’s the difference between a guy at your local Y, and LeBron James. This requires dedication, and players sometimes struggle for years to wrap their head around how to see the game at the highest level.

Players qualify for the World Championships, which take place over three days, by collecting hundreds of “championship points” at lower-level tournaments around the world during the preceding year; it’s sort of like tennis, where the quality of one’s play year round determines who is invited to the biggest tournaments. On Saturday, the competitors gathered at around 9 A.M. to play nine rounds of what’s called the “Swiss” format — they were given fifty minutes to play a best-of-three, with only complete matches counting toward their final score. (This means that if the players split the first two matches and run out of time to finish the third, it’s scored as a tie.) When the rounds were finished nearly twelve hours later, their records were assigned corresponding point values, with the top eight players making the “final cut” to play in a single-elimination bracket on Sunday to determine the champion. This meant that the bulk of play occurs on Saturday, swiftly validating — or mercilessly undoing — a long year of competitive play in a single day.

The biggest matches were broadcast on a wall-sized screen hanging in the middle of a football field-sized room, with rows of chairs set up for hundreds of fans to sit in and spectate. The competitors walked out to exuberant EDM music, pumping their fists and waving at their flag-bearing countrymen. They sat opposite each other, their cards laid out like tarot readings, and took turns moving these cards around the table so quickly that, watching from a distance, I could only register colors and words. A pair of commentators narrated and explained the action for casual fans: This player needed that card on this turn for his strategy to come together. When a necessary card was drawn, the crowd’s roar was immediate. Standing at the posted list of upcoming games, a group of pudgy tweens rattled off the names of players they wanted to watch with the glee of someone pointing out Derek Jeter across the street. At one point I saw Jason Klaczynski, the baby-faced three-time world champion whose winning deck from last year you can purchase through the Pokemon Company, autographing cards for a fan.

Apart from the main event, there’s something called the “last chance qualifier” — a single-elimination tournament comprising hundreds of players who can get in by surviving several rounds against each other. A pair of friends named Robert and Jonathan drove from Cincinnati to compete; they only had disparaging things to say about their own skills, yet retained the hope that they’d perform well enough to play in the big time. (When I saw them and asked how it went, Robert told me, “We both got wrecked.”) One player in the main event, Robby Weidemann, told me that he won the last chance qualifier a couple of years ago after flying from New Jersey to Hawaii, where the tournament was then being held.

Even for the players who’d begun the weekend with hopes of winning it all and quickly realized they wouldn’t, there was always a silver lining. Paul Johnston, a body builder, had returned to competition after college forced him into a four-year hiatus, during which he’d occasionally attended smaller tournaments with friends and borrowed their decks to compete here and there. He began the tournament with a loss and a tie, and knew he would have to win the rest of his matches to make the final cut. Despite the unfavorable odds, he finished out the day, and placed sixty-sixth out of a hundred and seventy-seven. (The smallest prizes, such as packs of cards, are first awarded to players who place at sixty-four and above.) “It was just good to get back in the game and be part of Worlds,” he told me. “I’m really proud of myself for making it.”

After a middling start, Michael Diaz, an eleven-year veteran and upcoming college freshman, decided to take the rest of the day off to hang out with his friends in and around the convention center. “I just wasn’t having a good time anymore. I really didn’t want to play Pokemon anymore, is what it comes down to,” he says. “I had no incentive to stay anyways, so I just went and got food with friends and forgot about it. Obviously it didn’t go as well as it could have but I had a good time seeing everyone again.”

Some players got what they were looking for, or something close to it. Altavilla started with two wins and two ties, and quickly realized he was playing well enough to possibly earn himself a final berth. “I came across one difficult situation, and someone who plays differently than me might not have noticed how to get it,” he told me. “The way I went about it made me feel confident — like I’m piloting this deck, and I can pilot it to different standards than most.” He then won four more games, and lost only one, putting him within reach of the top eight, but, because of a tiebreaker, which is determined by the winning record of opponents, he placed an agonizingly close ninth. “I thought I’d made it, and I looked and it was the most shocking thing ever,” he says. “I just missed. I was shocked for a bit and I couldn’t really speak or anything.”

After the initial shock, the reality of success set in: Although Altavilla didn’t play in the final, single-elimination bracket, he was the top American player. (Above him were three players from Portugal, two players from Canada, two players from France and one player from Japan.) Afterwards, he and his friends celebrated at Hooters; even his father, a former football coach, praised Altavilla for how far he’d made it. “It sucks because I didn’t make the top eight but it’s nothing to scoff at,” he said. “Now people are going to see my name and go, ‘Whoa, it’s that kid.’ Even if they see me as the kid who only missed it by one spot, they’ll still know who I am and that’s pretty cool.”

There are a lot of reasons why Pokemon has endured, but one of the biggest has to do with how community is encouraged within the game itself. In the game’s fictional storyline, the importance of becoming friends with your Pokemon is continually stressed from the beginning, so that when you meet another Pokemon fan in real life, it’s easy to find something to talk about because you already have so many friends in common.

During the final, which was between Canada’s Andrew Estrada and Portugal’s Igor Costa, several of the players I interviewed — and many more I didn’t — watched with the casual interest of NBA players sitting courtside at the Dunk contest. Their attention was held, for now at least. Before the tournament, the players talked about the spouses they hope to meet, the classes about to begin. The time to attend tournaments every other weekend will shrink. But after spending this much time with Pokemon, it will be hard to step away for good.

Jeremy Gordon is a staff writer for Pitchfork who lives in Brooklyn and plays games for children.