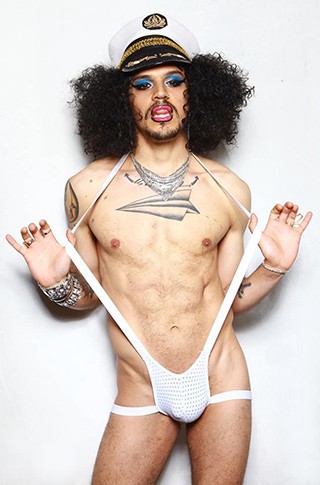

Men, Makeup, Money: The Boylesque of Rify Royalty

by Meagan Dwyer

“I really want to work out before my gig tonight,” Sharif Abaz said. “But I still have to fix my costume and my makeup is going to take forever. I have no time.” He picked up his outfit for the evening — a black mesh bodysuit, tank-top and shorts that cover the groin with a thick strip of spandex — and packed everything into a backpack. As he walked out, he took a final glance in the mirror by his front door, then brushed glitter from the night before from his eyelashes and rubbed his hand through his beard to check for untamed hairs.

Abaz arrived at the downstairs bar area of The Monster, a gay bar located on Grove Street in New York City a half hour before midnight. The dim room was crowded with sweaty young men and women, murmuring and anxious for a show. When the DJ announced the next set, Sharif took the stage in the darkened room and stood, waiting, with his head down. A moment later, the lights came up, revealing Abaz as “Rify Royalty” in full Dia de los Muertos makeup, with a long black veil covering his dark hair, a black gown over the mesh bodysuit underneath, and massive sexual attitude. He slowly raised his head toward the spotlight and began with a reverent rendition of Amy Winehouse’s “Back to Black” as he slowly stripped away his outerwear, then ground his hips on a chair as he lip-synched to Rob Zombie’s “Living Dead Girl” before moving to the floor, where he shot his legs in the air, exposing thigh-high stockings and high-heeled platform pumps. Piece by piece, the costume came off, until he was left in a black V tank-thong bodysuit, stockings, and heels, revealing a small collection of tattoos: an umbrella with rain underneath, pin-up girls, his mother’s name, scattered across the olive skin of his slender, toned frame. After the set, which lasted about ten minutes, Rify bowed as the crowd cheered and threw dollars at the stage. He exited stage right, clutching his earnings and teetering on five-inch heels.

Abaz, as Rify Royalty, has become a steady fixture in the downtown Manhattan and Brooklyn gay nightlife scene over the last year. He co-hosts “Hot Rabbit” at The Monster and the other week, he was featured at Bushwig, Bushwick’s annual drag variety expo. “I consider myself a nightlife entrepreneur,” he told me, when we met outside the bar after his set to share a cigarette; several people passed by us outside the bar and grinned at Rify, who was shirtless and still in his makeup, though he had changed back into a pair of jeans. “Being a part of the Brooklyn scene, all the rules of burlesque are off,” he said. He explained that there are lots of “fishy queens,” which are drag performers who can pass as “real” women; their body hair is shaved, most tattoos are covered, and the pronoun “she” is preferred. “But there are more bearded queens coming out and performing,” he said, pointing to his own facial hair, and maintains that he has been widely recognized as a “bearded lady” in nightlife. “Norms are being redefined. It does feel like there is a new wave coming through.”

Rify most frequently performs “boylesque,” which is a type of performance that combines drag costuming and burlesque stripping. They’re often set to a scene from one of hs favorite movies — his go-to is the abortion clinic scene featuring Jennifer Tilly in Dancing at the Blue Iguana. “Whether my character is perceived to be spooky, weird, funny, odd, it always manages to turn out to be seductive,” he explained, as he showed me a video on his iPhone that was taken at “TBA,” a party at Bizarre Bar in Bushwick, where he co-hosts a variety show the first Thursday of every month. In the video, Rify Royalty took the spotlight as a bearded, black-bobbed, tattooed Drew Barrymore in a short red bathrobe, pantomiming and lip-synching along with most of the opening dialogue of Scream. Behind him, another burlesque dancer, a woman, donned the film’s famous mask. Right as Rify, is about to be slain, both performers took off their costumes and danced to Destiny’s Child’s “Bugaboo.”

Go-go gigs at downtown gay bars, which consists of dancing nearly nude on a bar or small stage, are different from Rify’s “boylesque” performances. There’s little room for comedy or irony, and even a smaller amount for the mere suggestion of anything other than sex. It’s stripping without the pole and/or complete nudity. “Sometimes I take home eight hundred dollars on a weekend with go-go work, then sometimes I only make ninety,” he said. “But on average I walk away with a hundred and seventy five dollars a night. Minimum.” There is less preparation for a go-go performance: show up, wear little to nothing, dance to the music, be the literal embodiment of the fantasy. Let the customers touch you, and be liberal about it: do this, and you’ll leave the job with a handful of cash in to pull from your jock strap. A few days after the show at The Monster, I tried to attend a Rify Royalty go-go gig at one of the downtown bars at which he frequently performs on a very profitable night for him. When I showed up at the door, the bouncer took one look at me and immediately made up his mind. “No women tonight,” the guy said with a raised eyebrow and a knowing look. “Sorry.” I left, but I had an idea of what was going on inside.

The following morning, Abaz confirmed my suspicions. I asked about how he, as a performance artist trying to make a statement, felt about so much public sex within the bars. He blinked, as if surprised by the question, but his voice was even and consigned. “I’ve worked Black Party Expo. It’s massive,” he said. “They book a lot of sex workers, go-go boys, drag queens, everybody comes out and displays their best fetish look. It goes on all night. I did go-go there once. I’ve seen people have sex in public and it’s very much a part of my world.” With the constant sexual energy swirling around him, Rify Royalty has long chosen to be completely sober. He doesn’t judge others for indulging — maintaining that without mind-altering substances, nightlife may not be what it is — but he has never found a reason to partake. “I just really don’t care. It’s something I don’t do, but if you want to, you should,” he said. “I have lived a life of sobriety for so long, and I’m very open about my sexual presence in nightlife. I am very comfortable with that.”

A few weeks after I tried to catch his go-go performance, I hung out with Abaz again when he took Rify Royalty to the annual Coney Island Mermaid Parade. He was dressed as a mermaid with a large curly blue wig with multi-colored flowers, precise blue and green makeup, and a sequined fin that started at his hips and ended at his ankles. His exposed, masculine beard left no one wondering about his gender, and we could barely walk four steps without someone, or a group of people, stopping him to take his picture and complimenting him on his look. “I really want to break grounds in nightlife,” he said as we left the boardwalk about an hour later and to head back to the subway. “I think people are very set on rules and very heteronormative ways that we’ve been taught. There tends to be a woman-hating ‘don’t be femme’ attitude, yet these queens compete with each other constantly on who looks the most like a ‘real’ woman. People aren’t very free.” His face softened and his eyes began searching the in front of him, like he was lost for a moment, until he found his voice. “I want to host my own show one day, with tons of diverse performers, he said. “Whatever size you are, whatever color you are, in your very sexy look. If you have a six-pack, great. If you’re full-figured, great. Let’s make a sexy party.”

Meagan Dwyer is a freelance writer whose work has appeared in Resource Magazine, Thought Catalog, and Nerve. She lives in Brooklyn, where she is working on a novel.

Photos copyright Gizelle Peters, Stephanie Keith, and Maro Hagopian, used with permission

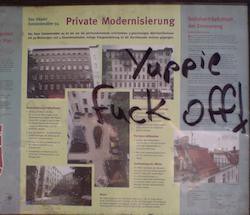

Has Your City Been Marked For Death Yet?

Has Your City Been Marked For Death Yet?

Lately, “new Berlin” has become shorthand for an under-visited European city that is cheap, fun, and up-and-coming. Ever since creeping gentrification and a massive rise in tourism have thrown into question the German capital’s status of the world’s “coolest” city, people have been racing to determine its successor. Candidates besides Leipzig include Krakow (Poland), Vilnius (Lithuania), Belgrade (Serbia), Tallinn (Estonia), and Warsaw (Poland). They share, to varying degrees, many of the elements that made Berlin famous in the 1990s: affordability, empty buildings that can be repurposed and a sizeable arts scene. But unlike Berlin, they won’t have the opportunity to develop their cool reputation slowly — and are just as likely to be ruined by the hype as they are enriched by it.

Does your small-to-medium-sized city have underutilized industrial real estate and a recognizable arts scene? Then your city is at risk of becoming cool. Doomed cities don’t get to be cool; stable, healthy cities don’t get to be cool. The cities that are marked for coolness are the ones with rich, varied potential — cities in some form of recovery, with uncertain but hopeful futures. For these cities, there may be no worse fate: Coolness is a guarantee that your residents will be displaced, that your local identity will be smithed into a blunt Brooklynish object, that your economy will be flooded with but then drowned by an influx of capital that sees your locale as a magical new asset class for which popping is a self-fulfilling prophesy. A passing mention in the right place at the right time — a casual “new Berlin” spoken here or written there — is an explicit threat to make a city’s residents tourists in their own homes. This doesn’t turn out well for the new residents, either: They’re an unwitting part of the plan, a mechanism through which outside investments are protected and multiplied. Once the city is flipped, their services are no longer required. They are then left with strangely high rents and the creeping feeling that they never really understood why they wanted to move in the first place.

Photo by domat33f

The Case for Abolishing Juvenile Prisons

by Sara Mayeux

Last month, archaeologists identified the first of the fifty-five human bodies recently exhumed at Florida’s Dozier School for Boys — a now-shuttered juvenile prison where, for decades, guards abused children, sometimes to death, despite cyclical scandals and calls for reform spanning almost a hundred years. Dozier represents an atrocious extreme, but the failures of America’s juvenile justice system are widespread. Whether labeled “boot camps,” “training schools,” “reformatories,” or other euphemisms, juvenile prisons have long harbored pervasive physical and sexual abuse. In one survey, twelve percent of incarcerated youth reported being sexually abused in the previous year — a figure that likely understates the problem.

During the “tough-on-crime” years of the eighties and nineties, states confined larger numbers of children than ever before, with the proportion of youth in prison reaching an all-time high in 1995. Since then, the tide has turned. Between 1997 and 2010, the rate of youth confinement dropped forty percent nationwide, partly because of declining crime rates, but also because of changes in how states respond to youth misbehavior. Fueled by a mix of family advocacy, costly lawsuits, scandals like the Dozier case, and recession-era pressures on state budgets, many states have enacted reforms to transfer youth out of statewide institutions into community-based programs. California, for instance, “realigned” its juvenile justice system in the aughts; New York passed similar legislation in 2012 and has recently closed several juvenile prisons, including the once-notorious Tryon Residential Center.

Even with recent declines, the United States still incarcerates tens of thousands of teenagers — about two hundred of every hundred thousand kids. (State-by-state data is available here.) Racial disparities are stark: Black kids are locked up at four times the rate of white kids. And forty percent of youth held in residential facilities are there for lower-level offenses like probation violations, nonviolent property crimes, and truancy.

In her recent book, Burning Down the House, journalist Nell Bernstein argues that juvenile prisons should be abolished altogether. “Bart Lubow at the Annie E. Casey Foundation, which supported this book, talks about the ‘my child’ test,” Nell told me. When reading about conditions in juvenile prisons, “we should ask ourselves, Would this be acceptable for my child if he had committed a very serious crime? If the answer is no, we have a moral responsibility to stop it. I have two thirteen-year-olds, so I think about that a lot.” I recently spoke to Bernstein about her book.

You don’t propose any reforms in your book because you say this is a system that can’t be reformed; it needs to be shut down. Did you come into writing the book with that position, or was it a conclusion you came to over time?

I tried to come in with a reporter’s open mind. But I have known kids who’ve been in this system for decades, so I did come in believing, from my own experience, that prison was a consistently damaging intervention that tended to make things worse for kids rather than better. Where my mind got pushed was when I began to delve into the research. Eighty to ninety percent percent of all kids, according to confidential interviews, have done something that could land them locked up. So that underscored the racial — I don’t even like to say disparities — the racism of what’s going on. My kid can do this; my neighbor’s kid can’t. And of course Ferguson has brought that into incredibly stark relief.

If you look at those eighty to ninety percent of kids who are all committing “delinquent acts,” it turns out that those who don’t get caught — because there aren’t police cruising their street and stopping them — or who do get caught, but are offered an intervention other than incarceration, tend to do very well. They basically grow out of it. Kids who are incarcerated, the chance that they will go on to be incarcerated as adults is doubled.

When you look at it through that frame, it’s just nuts. We’re taking the most vulnerable, oppressed group of kids in our country, and selectively subjecting them to an intervention that is known to turn them into criminals. The research helped me to understand that it’s not that we have two groups of kids, “delinquents” and “not delinquents” — delinquency is a developmental stage, and we can either help kids through and out of it, or we can do what we’re doing now, which is intervene in a way that keeps them stuck there forever.

So one issue is teenagers getting selectively punished for doing things that all teenagers do. But what about kids who have done something really serious?

I don’t think they’re two separate issues, because there aren’t many kids for whom a homicide or a carjacking is a first offense. Almost every kid I met, including those who were in for the most serious offenses, had started out at nine, ten, eleven, usually having suffered some kind of a traumatic loss, trying to make their own way on the street, and getting picked up for something very minor. The behaviors that lead to the more serious acts are often learned behind bars.

Nevertheless, there’s no ducking the question of what we do with the kid who actually endangers us. If you’ve read the book, I’ve had a kid put a gun to my head. I’ve felt what it means to be endangered. But it’s not just my personal suggestion that there are alternatives to prison that work better: Research shows that juvenile prison recidivism rates are seventy to eighty percent depending on the state — sometimes higher.

There are other interventions, like Multisystemic Therapy or Functional Family Therapy, that recognize that it’s relationships that rehabilitate. So a kid, if feasible, will stay at home, but will have a caseworker who is available twenty-four hours a day with a beeper and a very small caseload. The caseworker helps to connect, or reconnect, this young person with supports in the community, whether that’s services or natural supports like relatives. And if there are problems in the family, he takes the whole family as his client. Because that’s another issue with prison: If family problems are at the root of a kid’s delinquent actions, then airlifting him out of his family, traumatizing him, and then dropping him back into the same environment doesn’t make sense.

Has any state tried this kind of program on a large scale?

Many states have tried it, but not on a large scale. Ironically, Florida, which has one of the worst reputations in terms of some specific facilities — like Dozier, which is where they’re now digging up bodies — also has something called the Redirection Program, where they redirect a pretty large number of kids into these evidence-based models. But it still doesn’t approach the number who are locked up.

I guess the outcomes couldn’t be much worse than the current system.

And not just for the kid. As I said, I’ve experienced, if not violent crime, certainly the threat of it, and I don’t want to ignore public safety at all. But the truth is that an intervention that doesn’t work for the kid doesn’t help public safety. The fact that being incarcerated as a juvenile makes you much more likely to be incarcerated as an adult counters the argument that there’s a public safety benefit, except maybe for those years that the kid is gone.

In the book, you describe some horrific facilities. But you also visit a facility in Minnesota with a reputation for being comparatively humane, and you still come away ambivalent.

I really liked the warden there. I really liked the fact that when I said I wanted to see the place, he grabbed two kids who were walking by and asked them to show me around, and they were permitted to do so with no supervision. That never happened anywhere else I went. So I did feel that the kids could talk freely. There were motivational posters everywhere, and a lot of the things that the kids said closely mirrored those posters. There were more volunteers than there were kids. There were “cottage grandmothers” who baked cookies and milk. The place looks like a prep school.

But at the same time, each of these kids had spent time in the solitary confinement unit. That’s something that the UN considers torture when used on children for any amount of time. So here was this nice place, where, by international standards, they were routinely torturing kids. Because there has never been a time in history when we’ve successfully eliminated the abuses that take place in these facilities, no matter how many investigations and reports and waves of reform there have been, I don’t believe they can be eliminated.

But let’s say hypothetically that we could somehow, despite all historical evidence, create a juvenile prison where nobody was sexually assaulting kids, nobody was beating them up, nobody was placing them in solitary confinement. They still wouldn’t serve their purpose. If you think of the major developmental tasks of adolescence, they’re things like: Forming trusting relationships, which is taboo inside any locked facility. Learning to make decisions for yourself, which usually involves making some mistakes. There’s no margin of error inside a locked facility and you aren’t allowed to decide something as simple as what toothpaste to use. They live this very regimented life where they’re not allowed to make any decisions or ask any questions or form any relationships.

It sounds like an extreme version of a lot of high schools now, where the kids are very regimented and there are police on site. Kids are treated as though they’re dangerous.

That’s right, and what the kids who experience that learn from it is really morally corrosive. And they learn it from our fear, too — the purse-clutchers and the street-crossers. They learn that, as one kid put it to me, “Your skin is your sin.” Your criminality resides in who you are, before you even do anything, and what you do is secondary. They’re being told that who you are — being poor, being black, being male, whatever combination of those things it is — makes you, if not a criminal, a suspect.

One reason to be especially concerned about juvenile justice is that teenagers are different from adults and their brains are biologically different from adult brains. Still, some of your critiques of juvenile prisons could equally apply to adult prisons.

That’s absolutely true. My first book, All Alone in the World, is about children of incarcerated parents, so it looks at the impact of mass incarceration on family bonds and on communities. I think that we have a special moral responsibility to kids, but I absolutely agree that prison is very often a devastating intervention when it comes to adults. And it’s devastating to their kids. There’s this double-whammy aimed at poor kids of color who have their parents taken from them at really high rates — often for drug-related issues that would get treated as an illness if they had money — and then are themselves the target of the same system.

I should say there’s been a lot of progress on the juvenile front. There’s been a forty percent drop in the number of kids in juvenile facilities over about a decade. I’m also starting to sense a corresponding shift in public attitudes. When I go out and talk about this, I don’t get the same kind of pushback I did with my last book [in 2005]. So I think that if we seize this moment, we might get somewhere. People are starting to ask, “Are there lessons to be learned from the movement for change on the juvenile front that can be applied to the adult system? “

What can people do if they want to get involved with this issue?

Where people stand on juvenile incarceration, and on incarceration generally, has to be central to how we vote. If people want to get involved in political activism or organizing, the Annie E. Casey Foundation has a list of organizations in various states. There are a lot of people working on this, including groups like Justice for Families, which is led entirely by the parents of kids who are locked up. That’s a very powerful kind of advocacy. Every great civil rights movement has been led by those affected, and I do see this as a civil rights movement.

But there are two more things we can do. First, if you’re in a position to hire someone, think about hiring a kid coming out of a juvenile prison. Or if you have a friend who owns a business, advocate for that. Second, the most basic everyday thing we need to start with is looking at ourselves and our own attitudes, and — for example — not clutching our purses when we see a group of black male teenagers coming up the street. Not clutching our purses, not crossing the street. Just checking our own assumptions. It’s very widespread, the fear of these kids. And it sends them the message that they’re considered criminals and that they’re expendable, that society doesn’t really need them.

Sara Mayeux researches and writes about American criminal law. She’s a Sharswood Fellow at the University of Pennsylvania Law School and a PhD candidate in the History Department at Stanford University.

Photo by Connie Ma

The Mathematics of Re-Calibration

An electorate reshaped by a growing presence of liberal millennials, minorities, and a secular, unmarried and educated white voting bloc will most likely force Republicans to recalibrate. … When Ronald Reagan was elected president in 1980, white voters without a college degree made up 65 percent of the electorate; by 2012, that number had dropped to 36 percent.

The latter statistic is more complicated than it seems, in large part because more people than ever are getting college degrees — 33.5 percent of people between the ages of twenty-five and twenty-nine had a bachelor’s degree in 2012, versus 24.7 percent in 1995 versus 21.9 percent in 1975, according to the National Center for Education Statistics. Given that the rise has benefitted minorities and, in particular, women, while the share of people from low-income families attaining those degrees has “remained relatively flat over the last several decades,” what’s been eroded, in part, is the bastion of white men who were able to skip college and attain a middle-classish existence, leaving the remaining uneducated whites exposed and isolated, economically and, increasingly, socially — making them angrier and louder and, unfortunately for them, their views ever more toxic to the nationally minded politicians who once clamored for their votes. If Democrats can win today on issues of reproductive rights and gay marriage in the South — if only occasionally, for now — who will be left representing the poor, conservative white man in a decade?

Photo by Pierre

Privilege Supreme

“David Albouy, an economics professor at the University of Illinois, has created a metric, the sacrifice measure, which essentially charts how poor a person is willing to be in order to live in a particular city. Portland, he discovered, is near the top of the list.”

Tonight, New York City Crowns Its Best New App! But Will It Be the Racist One?

Tonight, Big Bill de Blasio awards the winners in the NYC BigApps competition. That’s a project of the New York City Economic Development Corporation. With mentors and judges from many, if not “all” walks of life, this project is one of the few rare ways that New York City might actually help a small business, while also helping to improve the lives of New Yorkers, or even making the city a better place in general. Cash prizes go to the best apps created out of city data.

But Mayor Bill will be treading on dangerous ground. Will the judges set him up for a disaster? Because among some great ideas and great executions in the finalist pool are some real nightmares. For instance, the infamous and much-derided app SketchFactor is actually a finalist in this program. Yeah, that’s the thing that lets various forms of app-using gentrifiers rate neighborhoods for just how uncomfortable they feel whilst passing through.

Certainly less evil — even good at heart! — but still as annoying is Reported, which was founded by a man who was unhappy that people don’t complain about taxis enough. (“There are 175 million NYC cab trips each year. Yet only 13,000 consumer complaints in 2013 about drivers,” is how his mission statement begins. Uh… huh.) He’s written an incredibly detailed piece (on Medium, of course) about how he kept a spreadsheet about all the cabs honking outside his house. He gives himself away early on when he says that Uber is a great experience because of the constant rider surveillance. His New York of the future: we’re all narcs, and we’re all customers.

I mean look, none of us want evil, racist and stupid cab drivers. We can all get behind this. But we already have an app for honking cabs. You lean in their window and yell “Shut the fuck up, asshole.”

Then there’s this thing that helps rich people use less electricity (who cares!) by turning down their Teslas and Nests. I mean… sure.

But the good news is that it’s certainly not all obnoxious “citizen as customer” proposals, so Mayor de Tall-io (yeah I’m still working on a nickname) has a chance of not humiliating himself tonight. Even when it technically is about “serving the citizen,” though, there’s good uses; why wouldn’t you want to be notified when you have new or overdue parking tickets, for instance? And building a user-friendly mobile-based front-end on food stamp assistance is actually a great idea. Why not have a global activities list for people with kids? A teacher collaboration network? Absolutely. And this app about heat complaints could be a great thing, instead of a tool for making New York City into a desiccated suburb. I even like this learn more about your water app. Water’s the thing we’re going to miss most when the terrorists take out the Delaware Aqueduct, after all.

New York City, September 14, 2014

★★★★★ Cool, fresh air through the window vied with frying bacon and won. The children were in long pants, newly sorted through to account for a summer of growth. The clarity out the window was prodigious, unreal, like eagle vision. A dignified old brown-brick apartment building, stair-stepping as it rose, stood out deep and solid among its flatter-faced neighbors. What was the light, the two-year-old asked, standing on the radiator cover, gesturing southward: six or eight blocks away, a tiny bright orange pinprick. It took binoculars to identify it as an ordinary sodium security lamp, burning in the dark shade of a rooftop superstructure. And far beyond that, what looked like the Newark Airport control tower was just that, and even past that, the National Newark Building. And a fat waning gibbous moon, like a painting of the moon, in among high cirrus clouds and little lower ones, now lavender-tinted, now peach, moving quickly downriver. And — yes, a dark shape flapping northward, presenting in the glasses the chocolate-brown body and wings, the white head and tail, an eagle itself. Out the door, bright streaks threaded the dark falling sheets of water in the fountain. Someone was wearing a puffy jacket; two other people, walking together, were in flip-flops. Clouds in the west briefly dulled the afternoon light. A wide battery-powered kiddie car, a red Mini Cooper, hummed slowly down the sidewalk. The playground was dreamlike, meaning a little bit numbing and unreal. Chalk had been scrawled heavily on the pavement, up and all over the kneeling concrete camel statue, and finally then just detonated into piles of colored powder. The two-year-old was subdued, clinging to the chain link or walking along a bench. Then a schoolmate arrived, and they mounted an assault on the slopes of the camel together, smearing themselves with chalk from collar to shoes. Sunset was total and overwhelming, the whole visible sky out the windows cycling from opulent through shocking and on to moody.

The Birth of Adulthood in American Culture

Three fictional madmen — two sociopaths and a narcissist — die on television. It’s a strange worldview that would take this as a sign of “The Death of Adulthood in American Culture”, but that is the premise of the lead essay in the New York Times Magazine’s culture issue, by film reviewer A.O. Scott.

The unfortunate endings of Tony Soprano of “The Sopranos” and Walter White of “Breaking Bad” — plus Don Draper of “Mad Men,” whose elegant silhouette is likely to plummet off a skyscraper soon, according to some fans — signify to Scott the “slow unwinding” of the very idea of adulthood as it was formerly understood, a principle inherent in the patriarchy. “The supremacy of men,” Scott writes, “can no longer be taken as a reflection of natural order or settled custom.”

But is it “masculinity” that is in decline, or “maturity”? How tightly are the ideas of “manhood” and “adulthood” tied together? Not very. A closer look would suggest instead that adulthood is only just beginning to come to American culture.

Draper, Soprano, White: Each of these tragic exemplars of “adulthood” is destroyed exactly because of his failure to behave like an adult. All three are doomed, overgrown boys, a little reminiscent of the lost donkey-boys of Pinocchio’s Pleasure Island. They are at bottom faithless, immoral, bereft of empathy or foresight; despite their moments of awareness and regret, they are reckless and essentially very stupid men. They are lousy not only at being adults, they are lousy as men, too, even if there is much in all three to admire: Don Draper’s restraint and intelligence at the conference table, Tony Soprano’s intermittent tenderness, and his protectiveness toward his family, and Walter White’s ingenuity and pluck. But in the main they are frauds who merely assume the trappings of “adulthood” in order to participate in a society that would reject them if it knew the truth.

Television shows are mass-market popular fiction, where conventional morality must and will eventually win the day. (“That is what fiction means,” as Wilde says.) What is demonstrated in these three cases is not only regular TV logic, but the mainspring of what John Gardner called “moral fiction” — a dramatization of the bad consequences of selfish, immature action. It’s not to do with having “killed off all the grown-ups” as Scott has it: quite the contrary. It’s adulthood defined for the audience by its very absence on the screen.

A child is a person whose whole world is self, and an adult is one who has transcended that unfortunate and lonely condition. Though some Americans over the age of twenty-one cannot be considered adults by this definition, most, perhaps, can, if they want to be.

A.O. Scott doesn’t like it when he sees adults reading young adult fiction:

I will admit to feeling a twinge of disapproval when I see one of my peers clutching a volume of “Harry Potter” or “The Hunger Games.” I’m not necessarily proud of this reaction. As cultural critique, it belongs in the same category as the sneer I can’t quite suppress when I see guys my age (pushing 50) riding skateboards or wearing shorts and flip-flops, or the reflexive arching of my eyebrows when I notice that a woman at the office has plastic butterfly barrettes in her hair.

I am not a fan of Harry Potter. But who can cast aside the claims of young adult fiction to the most serious consideration, when Animal Farm and The Giver, Cat’s Cradle and To Kill A Mockingbird must be included (along with Huckleberry Finn, which Scott treats at some length)? These books are not remotely “carefree juvenilia,” though young teenagers are commonly assigned most or all of them as school reading. It seems silly to have to point out the glaringly obvious fact that a lot of “adult” books are plain terrible, and they can be terrible every which way. But for the purposes of this discussion, let’s be clear that many “adult” books are way more “immature” than even a half-decent YA novel (meaning that the author has ideas to share that will be of some interest and use to an adult reader).

Even a relatively light-on-ideas speculative novel for young people (Divergent, say) is about a thousand miles ahead of half the “adult” stuff on the bestseller lists — get-saved or get-rich Life Full of Purpose snake oil, dumb, pompous narcolepsy-inducing would-be Literary Fiction, warmed-over Dean Koontz etc., etc., etc. I mean this not just in terms of entertainment — although, that too — but in terms of providing useful, interesting moral and philosophical questions for the reader to think about, and test against his own ideas.

Adults might read books for and/or about young adolescents for a ton of different reasons, such as:

Nostalgia: in order to reminisce over that formative period in their own lives

Parenting (a): to understand their own children (and/or their children’s teachers) better

Parenting (b): to learn alternative parenting ideas and strategies

Curiosity: to compare the world that is past with the present one

Anticipation of the Future: to understand where the Zeitgeist is headed

These are all in addition to the very sound motive of “escapism” or plain fun. All are valuable adult literary experiences, and I can’t begin to fathom how anyone would think otherwise. Also, please note: no young adult novel is written BY adolescents. They can’t write novels: they are too young! In any case, I don’t think there is a reader of any age in all this great land who will argue that To Kill a Mockingbird compares unfavorably in any way whatsoever with the “adult” novel Fifty Shades of (“Argh!”) Grey.

(Also, who is this outrageous flibbertigibbet at the Times with the “plastic butterfly barrettes in her hair”?! Please step forward, identify yourself and produce the accessories that have so deeply offended our self-appointed representative of the “grown-ups.” Are they PINK? I should like to know.)

Scott couches his essay in layers of awareness about being part of the problem — he is a white man approaching the age of fifty — and that is all to the good. He doesn’t quite approve of himself for sneering. But he is still a little bit upset about the end of the days when men were men, because they “had something to fight for, a moral or political impulse underlying their postures of revolt.”

But in fact nothing has changed and Scott points this out himself. In a bewildering rumination on Leslie A. Fiedler’s “magisterial” Love and Death in the American Novel (1960), Scott says first that Huck Finn is an infantilized YA hero, “the greatest archetype of [the] impulse” of literary childishness, and then, five seconds later, goes on to claim that that Huck Finn “exposed the dehumanizing lies of American slavery.” If Huckleberry Finn is the model of infantile American fiction, did “adulthood in American culture” die in 1884, or 1960, or with the (possible) demise of Tony Soprano? Should today’s adults be reading Huckleberry Finn, or not?

Scott’s view of the oeuvre of Judd Apatow is nearly as baffling as his view of YA literature. He thinks that Apatow’s bromedies are dumb and juvenile, and that the people who love them are attempting, embarrassingly, to prolong their own childhood. But if the flight from adulthood is all about avoiding marriage or “responsibility”, Apatow’s anti-heroes do a terrible job on that front. The end of nearly every Apatow film finds each hapless young man embracing the most absolutely conventional “adult” values: getting married, having the child, demonstrating loyalty to the friend, saving the business, in a display of mainstream morality conformist and, indeed, conservative enough to satisfy Peggy Noonan. If anything, Apatow’s movies are a guide for man-children to become adults, while still maintaining some aspects of their childhood selves intact. They can still be loved and valued, still enter the adult world, and still love action figures. You might say, they can Have It All. (Which would be very nice, I think! And I hope they will.)

All this knocks the center out of Scott’s argument, so that by the end it is completely diffuse: “a crisis of authority is not for the faint of heart. It can be scary and weird and ambiguous. But it can be a lot of fun, too. The best and most authentic cultural products of our time manage to be all of those things. […] The world is our playground, without a dad or a mom in sight. I’m all for it. Now get off my lawn.”

What does that even mean? If he’s all for it, then why do we have to get off his lawn? How come he is not just inviting everybody onto his lawn?

The very best “formal critical discourse” takes as its subject the whole of culture, the whole of human reality, and that has long been clear; we’ve moved way, way, way past the sniffy superiority of “Notes on Camp.” Umberto Eco wrote movingly and hilariously on “Peanuts” and “Krazy Kat” in the New York Review of Books in 1985. Nearly thirty years ago! (There are far earlier examples of the most exalted critics’ serious consideration of the products of mass culture, but that one will do just fine.) How is it possible that we are still hearing these worn-out calls for “adult” culture?

Here we can connect our earlier claim that adulthood is a matter of less selfishness and more empathy. Because an adult who has moved beyond the imperatives of his own ego no longer needs to show that the people or things he admires meet some (actually) childish, ego-stroking standard of “adulthood” — nor of “coolness” or “discernment,” for that matter. An adult is a person whose existential center of gravity has moved out from himself and into the world; he naturally just gives more attention than he takes in. That is, he doesn’t need attention for himself any longer; he’s more interested in what’s outside himself.

No man is an Iland, intire of it selfe. If we want even to try to understand anything of ourselves, of the world, we must pay attention to everything and everyone there is. That is why it can be as grown up and serious as all hell to read Young Adult literature, provided it’s by real people and has real ideas, and if the same is true of the person reading. It is great to read anything, watch anything, meet anyone, go anywhere. And then we will be learning something all the time.

That’s why American culture is becoming more adult, rather than less. Educated Americans no longer think of their country as the center of the universe, but see their country as one among many; American novels, plays and stories seek a diversity of voices and opinions; same with the better American schools and workplaces. In my lifetime, despite some really terrible setbacks — in politics, especially — Americans have been slowly but steadily growing into the literal truth of the idea that all people are created equal, and that all voices should be heard. Adulthood, in short, is in the eye of the beholder, whether the beholder is watching The Sopranos or reading The Hunger Games.

Maria Bustillos is a writer and critic in Los Angeles.

When Your Grandmother Loses a Toe

by Matthew J.X. Malady

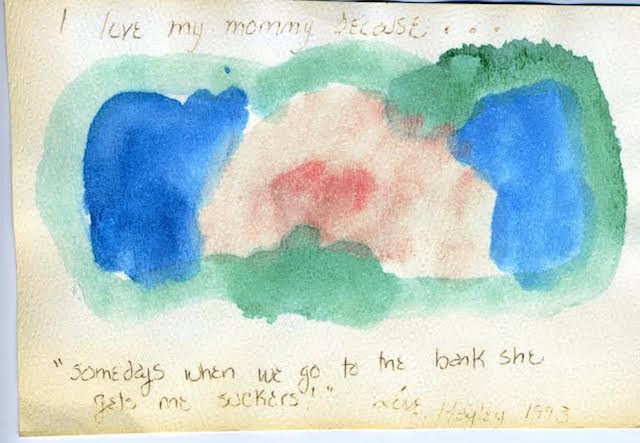

People drop things on the Internet and run all the time. So we have to ask. In this edition, Business Insider assistant editor Hayley Hudson tells us more about a note she wrote to her grandmother as a young child about the prospects of having only four toes on one foot.

My mom sent me this today. Note I wrote to my grandma before her surgery. Shows the human capacity for empathy. pic.twitter.com/6xsAncQ9BM

— Hayley Hudson (@hayhud) September 3, 2014

Hayley! So what happened here?

When I was eight, my family learned that my grandma — my mom’s mom — needed surgery on her foot. She had skin cancer, and it had started to spread. Her doctor caught it early enough that operating would take care of everything and she would be fine, but as you can gather from reading the note, she was going to be losing a toe.

So my mom sat me down to write a card to mail to my grandma’s house in Iowa. I don’t remember the exact instructions she gave me, if there were any. She probably assumed that I’d say something sweet, and the whole thing would be effortless. Instead my words came out sounding like an answer to a test question at a medical school for sociopaths.

“Describe this procedure. Don’t get too technical. Extra credit if your bedside manner is unhinged.”

This reminds me of another childhood art project. One year for Mother’s Day, everyone in my preschool class had to pick a reason why we loved our moms and paint an illustration. I couldn’t think of a reason.

The girl sitting next to me had picked something like, “I love my mom because I do!!!” I remember seeing that and thinking, okay, that’s maybe true for me too, but is it a reason? I decided it wasn’t. Not technically.

After weighing my options for a good ten minutes, I eventually did settle on a piece of hard evidence that I believed would absolutely convince any skeptical reader that my mom was, in fact, worthy of love.

In both cases, I seemed to be thinking, “Okay, I’m not sure what to do here, so I’m just going to pick a fact and say it.”

The note to your grandmother is so direct and efficient. No words are wasted. It’s kind of a masterwork in that way. Do you still write like that? Also, I’m curious about something: Could you draw me a toe and a four-toed foot so we can compare your art skills then vs. now?

It’s a very direct method of communicating. I prefer when people tell me like it is, so, you know, I would treat my own grandmother with the same respect.

“Here’s exactly what’s going to be happening to you, Grandma! Remember? Remember now? Four toes. Count ’em.”

Part of me must have been in on the joke. I sound as naive as I did in the caption of the painting from preschool, but I was four years older. You’d think by then I would have known that when someone is going for surgery, you just wish them good luck.

So maybe I was starting to develop a sense of humor as a coping mechanism. I mean, we don’t just wake up one day as suddenly cynical adults. Kids can find their own ways to mask vulnerable feelings.

Oh, and here’s my stab at redrawing this:

Lesson learned?

Never feel.

Just one more thing.

I asked what my grandma thought about the note today. She said: “It was sweet. You actually thought it was going to hurt.”

Matthew J.X. Malady is a writer and editor who was in New York but is now in Berkeley.