Erykah Badu, "Street Hustle Experiment"

“I just, kind of always wanted to see what it would be like to, you know, sing for money on the streets. So what I’m going to do is, I’m going to find a good place.” Erykah Badu busks in Times Square.

Meet Perfection

by Awl Sponsors

Brought to you by Absolut.

From seed to sip, every drop of Absolut Vodka is expertly crafted by generations of farmers and distillers from the small village of Åhus, Sweden — in a region with more than 400 years of superior vodka-making expertise. What’s their secret? High quality, locally sourced ingredients — pristine aquifer water & pure winter wheat (the latter carefully selected in partnership with 450 local farmers).

These high quality ingredients, in conjunction with the care and attention of a village that has been crafting vodka since 1879, results in a smooth, rich vodka that transforms any cocktail.

To learn more about how Absolut is crafted please visit: meetperfection.com.

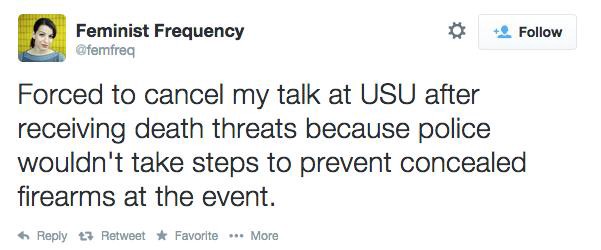

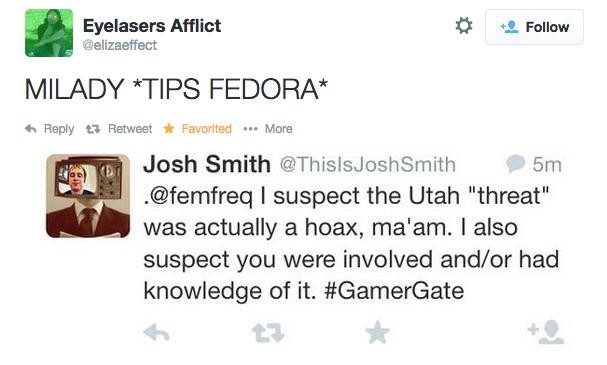

Gamergate in Posterity

The hideous mass lash-out known as #Gamergate is snowballing into an unlikely but genuine historical moment. This rings true:

What we have in Gamergate is a glimpse of how these skirmishes will unfold in the future — all the rhetorical weaponry and siegecraft of an internet comment section brought to bear on our culture, not just at the fringes but at the center. What we’re seeing now is a rehearsal, where the mechanisms of a toxic and inhumane politics are being tested and improved. Tomorrow’s Lee Atwater will work through sock puppets on IRC. Tomorrow’s Sister Souljah will get shouted down with rape threats. Tomorrow’s Tipper Gore will make an inexplicably popular YouTube video. Tomorrow’s Willie Horton ad will be an image macro, tomorrow’s Borking a doxing, tomorrow’s Moral Majority a loose coalition of DoSers and robo-petitioners and scat-GIF trolls — all of them working feverishly in service of the old idea that nothing should ever really change.

The ideology that leads a young fan of Call of Duty to tweet threats of violence at women who dare make or write about video games is old and broad and thoroughly rotten. His venues, however, are new: They lower the bar for participation, bringing words that would have been shared in private out into the open, on the internet, turning cruel jokes shared between gamers on the couch into real and terrifying threats posed in public.

The urgent consequence is that this private speech projected into public is harassment. But a future consequence, the closest thing to a silver lining that #Gamergate has, is that at least some of this speech is permanent. The worst harassers and instigators are mostly anonymous, but their legions of supporters and fans and enablers are not.

The older you are, the more likely it is that you’ve said or believed some truly loathsome things in your life; that you’ve been, for lack of a better term, on the wrong side of history. But when you were, you were probably among your cohort — it is in all of your best interest to bury those words, exchanged over beers or in class or over email, forever. This is cowardice and conspiracy. This is also very easy. Ask the old people in your life.

These young men feel like they’re among their cohort, too, but their actions are both material and recorded. They’re not just enabling the status quo with private speech and public silence — their anger and error is being recorded for posterity. I mean maybe all this text gets swept away as the internet remakes itself again and again, taking all the “feminists are ruining my life” and “but it’s actually about ethics in games journalism!” comments with it. But maybe it doesn’t! Maybe this post on gaming forum NeoGAF (via) will play out in slow motion over many years, for thousands of people, as they look back on their own words frozen in amber:

It actually took far, far longer than I’m comfortable with for this to sink into my thick skull. When you finally detach yourself from GG, and move away from the constant reinforcement the group provides that “no, we’re doing the right thing! These are the bad guys, remember how bad they made you feel? We’re doing the RIGHT THING!” you look and see holy shit.

Maybe there will be some small measure of accountability in the far future, not just for public figures and writers and activists, but for all the people who could not or would not see their “trolling” for what it really was. Maybe, when their kids ask them what they were like when they were young, they will have no choice but to say: I was a piece of shit. I was part of a movement. I marched, in my sad way, against progress. Don’t take my word for it. You can Google it!

Why My Baby Doesn't Eat Animals

Having a child means that you, as a parent, wield incredible power. You can dress your baby exclusively in green, or never let her hear Simon & Garfunkel (as if) or Iggy Azalea (oops, I wish). Arguably the greatest power arrives with the introduction of “solid food” into your baby’s mouth, around the time they are six months old. I thought for a very long time, even talking it over with friends, about what Zelda’s first food should be. I was told by my doctor to start with something naturally mushy. I settled on a daily vacillation between the avocado and the banana.

Zelda didn’t want to wait until she was six months old. By the time she was four-and-a-half months old, she was trying to grab food from my hands, or off of my plate. So, one afternoon, in a less momentous fashion than I had imagined, I mashed up both an avocado and a banana and offered them to her, minutes apart. She took the spoon from me and hoisted it into her mouth herself. She made a face, but she was also “chewing” as she handed the spoon back to me for a refill. A lot of what I gave her on the spoon fell out of her mouth and onto the floor, where the dog was anxiously waiting. But Zelda clearly understood the ritual: The next day, when I fed her sweet potato which I had peeled, steamed, and pureed, more went in — and stayed in. In less than a week, she’d been introduced to green beans, peas, carrots, and leeks (which I steamed with a small piece of potato and pureed for her).

Now, at eight months old, with just two teeth, Zelda can chomp down anything you hand over, in smallish chunks. She likes her food pureed or not, warm or not. Toast, strawberries, steamed broccoli, pasta noodles. She eats a lot, usually feeding herself, and often sharing with the dog. The one thing Zelda has never tasted, however, is an animal.

All children love animals. From the time they’re born, their rooms are festooned with stuffed ones; their books are filled with talking ones; their clothes are plastered in them. Birds, giraffes, elephants, sharks, octopi. The whole ark is found in a child’s life, and even before they can walk or talk, they recognize and smile at the family dog, or a stuffed monkey. They recognize a face, whether it’s animated or human or not.

I distinctly remember the day that I put two and two together about the truth of eating animals. I was in second grade, and to be honest, I didn’t do the addition on my own. My teacher plainly announced to my class that hamburgers were made from ground up cows. She was an obese woman, and I don’t know if she was a vegetarian; I remember that her favorite food was blueberries. There was some discussion of this amongst my classmates, I am sure, but I don’t remember because I was finishing up the math in my head, and within my stomach was a sinking feeling that I had known the truth for some time.

I went home that night and at dinner, my mother served something which was made of beef. “What animal is this?” I asked. At the time, I thought the look that came across her face was anger, but now my guess is that it was an “oh shit” moment, surrounded as she was by my three brothers who would also have questions. At my house, you ate what was put in front of you. It has to be this way in a family of six; the only successful stand I ever recall making was one against split pea soup when I was about five years old.

My mother told me we would talk about it after dinner, and we did. We had a long discussion about chickens and pigs and cows, and even deer, because there were hunters in my family. Roast? That’s beef. Bacon? Pig. Ham? Also pig. It was eye-opening and fascinating to me, and my mother patiently explained it all. If my mother were alive and I asked her about this day, I’m sure she wouldn’t even remember it ever happening, but it was a life-changing event for me, and it started a lifelong, very complicated relationship with meat eating.

I didn’t stop eating meat for the first time until I was in middle school. My mother supported me: She didn’t make special food for me, but she allowed me to not eat the meat she served, and made sure there were enough other things on offer that I could consume without suffering from malnutrition. I don’t know how long this phase lasted, probably not very long. I stopped eating meat again in high school, and then college. Sometimes these periods lasted a year or two, sometimes just a few months. But it was always for the same reason: I love animals. I don’t think of it as a “political” decision, because even in the best farming scenarios, I would still have trouble choking down something which I know had had feelings, thoughts, a life worth living.

The last time I ate an animal was in June of 2008, if I gloss over the one fish sandwich I devoured, guilt-free, while seven months pregnant. I was surfing the web and found a story in the Daily Mail about a little pig named Cinders who lived on a pig farm North Yorkshire. Cinders was afraid of mud, so her owners had gotten her four little rubber boots, which she wore and happily trotted around the farm in. That was it for me.

When I was pregnant, I assumed that like our family, Zelda wouldn’t eat meat, but I didn’t have reasons for it other than, “Well, she’ll eat what I eat.” My doctors assured me that baby vegetarians, like adult human ones, are just as healthy — and often healthier — than meat eaters. After Zelda was born, however, still a little thing, swaddled up all tightly, I realized that I had the opportunity to give her a very precious gift — to my mind — an opportunity which I’d never had.

If I never fed her an animal, or allowed anyone else to, I realized, she will never have to learn the truth about eating animals and feel like she’s been cheated or lied to. She’ll never have to feel guilt or confusion about it, or anger towards me, her mother, who had been lovingly spoon-feeding her the same precious animals she cuddles every morning when she wakes up. She’ll get to make that decision herself when she is old enough to understand what it means, like many others.

I don’t harbor any illusions about the fragility of children. They are often better at accepting harsh realities than adults. I remember clearly being six years old when a great aunt died, worrying over my brother who was sixteen months younger than me. I was born old, a worrier to the core, so rather than wallowing in my own sadness, I bit my lip and thought to myself, “How are we going to explain this to him? What will he think?” “She’s dead,” I overheard him telling our even younger brother. “That means we won’t ever see her anymore, and she’s done living.” So I know Zelda will probably get to the age of four of five or whatever, and I’ll explain to her that most people kill, cook up, and eat her beloved pigs, chickens, and cows. I’ll expect sadness or confusion or anger, but I know it’s so possible — likely, even — that she’ll look up to me and say, “Let’s have the chicken tonight, then.”

I love to cook. I still cook a turkey every year for Thanksgiving, because I love having large groups of people over for holidays and occasions, and I have no interest in foisting my eating habits upon the adult masses. Cooking is about sharing and joy and love. Eating with my daughter, even at the messy age of eight months old, is a joyful experience I am grateful to have day in, day out. So, when she’s grown up, she can eat whatever she wants, and I’ll happily cook up Cinders for her if she likes. Until then, we’ll just keep talking to the animals, and sharing our plums with the dog.

Author’s Note: Everything in parenting now has a hilarious and often confusing name applied to it. The technique which I have used to begin feeding my daughter food is known as “Baby Led Weaning,” which involves giving a baby, even at six months old, actual food which hasn’t been pureed, to experiment and chomp away at at will. A piece of bread, a frond of steamed broccoli, a cooked rigatoni, anything goes. Choking hazards to babies of this age, the wisdom goes, have been vastly overstated. I have found this to be true of my own daughter, though, as with everything, I’m not religious about it and also feed her plenty of pureed food, too.

THE PARENT RAP is an endearing new column about the fucked up and cruel world of parenting.

Laura June is a writer and a very cool mom. She is also the author of “The Hunger Games.”

Photo by Michael Choi

Rewriting History in Real Time: A Social Media Guide

In the process of trying to figure out when your cousin’s birthday is, or looking at photos of your old partners’ weddings, or deciding whether or not to attend your 10/20/30/40-year reunion, there’s a reasonable chance you will come across some variation of this headline on Facebook. Beneath it will be comments from friends and family and strangers, in which the dinner table arguments of a decade ago are relitigated. The details, which were foggy in the first place, are now foggier. Someone will probably bring up beheading immediately.

The source for this post — which comes from a profoundly cynical, and popular, news project called the Independent Journal Review, which treats news stories like ideological choose-you-own-adventure books — is “The Secret Casualties of Iraq’s Abandoned Chemical Weapons,” a blockbuster report by C. J. Chivers. It will not come up, because it has been buried behind at least one layer of translation — from boring, caveated “writing” into pitched and colloquial social patois (but still with a VERY CREDIBLE font). Its new headline, or headlines, are not about the story so much as they are about their prospective sharers, and so those are the terms in which it will be discussed. The new versions of the story say, “I was right” or, at least, “you were wrong.” The structure within which they appear is such that engaging with the post — sharing, disagreeing, Liking — is much easier than investigating is provenance, even if it’s just three clicks away.

The Times story contains many “shareable” parts but its core is brutally unsharable: Behind every revelation is a complicating and depressing explanation.

For example:

In all, American troops secretly reported finding roughly 5,000 chemical warheads, shells or aviation bombs, according to interviews with dozens of participants, Iraqi and American officials, and heavily redacted intelligence documents obtained under the Freedom of Information Act.

But:

during the long occupation, American troops began encountering old chemical munitions in hidden caches and roadside bombs. Typically 155-millimeter artillery shells or 122-millimeter rockets, they were remnants of an arms program Iraq had rushed into production in the 1980s during the Iran-Iraq war.

All had been manufactured before 1991, participants said. Filthy, rusty or corroded, a large fraction of them could not be readily identified as chemical weapons at all. Some were empty, though many of them still contained potent mustard agent or residual sarin.

And:

The United States government says the abandoned weapons no longer pose a threat.

But:

[N]early a decade of wartime experience showed that old Iraqi chemical munitions often remained dangerous when repurposed for local attacks in makeshift bombs, as insurgents did starting by 2004.

Double but:

Others pointed to another embarrassment. In five of six incidents in which troops were wounded by chemical agents, the munitions appeared to have been designed in the United States, manufactured in Europe and filled in chemical agent production lines built in Iraq by Western companies.

When you encounter this story, it is likely that it will be in the context of someone you know suggesting that President Bush and his supporters are owed some sort of apology; that for all that smoke in the early 2000s, there was actually fire. By now the memory of what those years were actually like has been completely suppressed:

Saddam Hussein’s armoury of chemical weapons is on standby for use within 45 minutes, Tony Blair’s dossier revealed today.

The Iraqi leader has 20 missiles which could reach British military bases in Cyprus, as well as Israel and Nato members Greece and Turkey.

He has also been seeking to buy uranium from Africa for use in nuclear weapons. Those are the key charges in a 14-point “dossier of death” finally published by the Government today.

In an introduction, Mr Blair says that the evidence leaves Britain and the international community no choice but to act.

At its core, this is a story about a decades-long failed project in American foreign policy and its human cost. It’s depressing — it’s something that no healthy person could feel good about, even if it somehow proves them right. Luckily, some of the loudest voices on the internet — new de facto gatekeepers, even more agile and unaccountable than the television and radio hosts that came before them, with audiences who know what they want to hear — have a solution to this problem. And they’re happy to share it!

New York City, October 13, 2014

★ The clouds, torn in places early, thickened and assumed the color of old fingernails. The ambiguity resolved into a faint drizzle. A gloomy chill seeped through the office. Out on the fire escape, it was humid and a little less cold. The indoor hoodie stayed on for the commute — accidentally at first, and then out of necessity. Uptown, there was just enough light left to search the playground till the fallen leaves began to look too plausibly like they might be a yellow diecast anthropomorphic car. The drizzle rematerialized and as night fell it intensified into a soaking mist, till umbrellas came out and the sidewalk grew slippery.

Youth Harnessed

“While some elementary schools no longer have recess, and people like New Jersey Governor Chris Christie argue that school days should be even longer, a few schools are already moving in a different direction. Some are testing out standing desks, and realizing that a little bit of activity can actually improve attention spans. Others, like Ward Elementary in Winston-Salem, North Carolina, are starting to fill classrooms with exercise bikes, so students can work out while they learn.” — Thought experiment: Would the ethical status of this program change, in any way, if the exercise bikes were used to generate electricity? The MOOC machines will need charging.

Eye Contact in the Highest Court in the Land

Eye Contact in the Highest Court in the Land

by Ryan Rodenberg

Supreme Court Justice Stephen Breyer looked at me and nodded at 1:33PM Eastern Daylight Time on January 21, 2014.

I arrived early that day. You have to. Seating is limited at the Supreme Court. At 6:04AM, I was eighth in the queue. Snow was imminent. Most schools in DC, Virginia, and Maryland were closed. The federal government was closed too, but Chief Justice John Roberts kept the doors of justice open. It takes more than a few flurries to close this Article III court.

The day’s docket was unique. Instead of the typical two cases, three oral arguments were on the schedule. I had no personal stake in the outcome of any of the disputes. I was simply interested in observing the process and witnessing the back-and-forth between the justices and lawyers in real time. Neither live audio nor video are allowed at the Supreme Court, so attending in-person is the only option. The justices’ questions and commentary, coupled with their body language and tone of voice, sometimes foretell how the cases will be decided. Armed with first-hand observation, journalists will often turn soothsayer after attending oral arguments.

At 7:25AM, the line had yet to move. I was just trying to stay warm, marching in place. I tried not to look strange, but it is hard not to look strange while doing high knees near the entrance of the nation’s highest court. I re-read my papers summarizing the trilogy of cases to be heard. First up was Harris v. Quinn. Harris was one of several state employee plaintiffs. The latter, Pat Quinn, is the governor of Illinois. I read the “question presented” three times and my confusion increased. My sense was that the dispute had something to do with a government worker who did not want to the join a union.

The second case was Petrella v. MGM. The case stemmed from the classic boxing movie Raging Bull. That sounded pretty cool. The overriding legal dispute centered on whether the doctrine of laches can be invoked as a defense to a copyright infringement claim. That didn’t sound very cool. My Black’s Law Dictionary started collecting dust years ago. I couldn’t recall what laches meant.

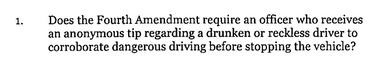

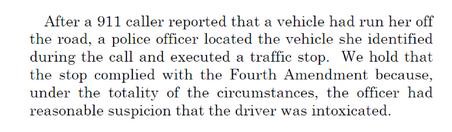

The third case, Navarette v. California, resonated. The issue was straightforward:

I thought this one could be lively. Topics like anonymous tipsters, traffic stops, and the Fourth Amendment’s prohibition on unreasonable searches and seizures were sure to elicit a number of interesting questions and hypotheticals from the justices. Fourth Amendment cases also tend to result in unpredictable splits along the Supreme Court’s ideological divide. Just two years ago, in a high-profile case involving the warrantless use of a GPS device attached to a suspect’s vehicle, left-leaning Justice Sonya Sotomayor joined Justice Antonin Scalia’s 5–4 majority opinion and conservative Justice Samuel Alito wrote a concurrence. I was curious if this, or something like this, might happen again.

The line started moving at 8:45AM. After a security screening, I followed others to the coat check room. Electronics are not allowed in the courtroom, so I put my phone in a tiny coin-operated locker. I then trailed a group of others up a staircase. At 8:55AM, I lined up behind what must have been one hundred people. How did so many people get in front of me? I wasn’t sure, but I knew that the only thing separating us and the courtroom where Roe v. Wade, Miranda v. Arizona, and Bush v. Gore were decided was what looked like a thirty foot tall maroon-colored blind hanging all the way to the floor. The thick curtain was pulled back and an usher led us to our seats. The wooden benches were huge, reminiscent of pews at an old church.

I took my seat for an hour-long wait. Oral arguments were slated to start at 10:00AM. The courtroom was at full capacity.

For the first two cases — Harris v. Quinn and Petrella v. MGM — I sat in a far corner, at least fifteen rows behind the front portion, which is reserved for the lawyers arguing the cases. A huge white column was to my immediate right. All nine justices were within my line of sight, but I couldn’t see any details. I was too far away. Facial expressions were a blur. Some of the justices were difficult to hear when they turned away from their microphone. At noon, the court recessed for a break. Navarette v. California was next, after lunch. I dashed to the in-house cafeteria and grabbed a half-dozen chocolate chip cookies. The Supreme Court cafeteria has great chocolate chip cookies.

At 12:35PM, I returned to the secondary security screening for re-entry to the courtroom. There were more security guards and administrative personnel milling around than there were would-be attendees. I was ushered in to a near-empty courtroom. I was seated in the second row, near the curved and elevated platform where the justices sit. Chief Justice Roberts sat in the middle, flanked by four justices on each side. Proximity to the Chief is based on seniority. Justice Scalia and Justice Anthony Kennedy, both nominated by President Reagan, were closest. Justice Sotomayor and Justice Elena Kagan, President Obama’s two appointees, were on the far wings.

I was about twenty feet from Justice Sotomayor’s chair. Justice Breyer, twenty years into his tenure on bench since being nominated by President Clinton in 1994, was seated immediately to her left.

At 1:00PM, the justices entered. Everyone rose. I glanced around. The continuing snow had clearly affected attendance.

The Chief Justice introduced the case with considerable brevity:

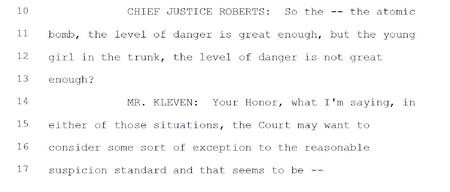

Mr. Kleven represented Lorenzo Prado Navarette and Jose Prado Navarette, criminal defendants contesting their arrest for marijuana possession on the theory that a single anonymous (and uncorroborated) tip failed to satisfy the reasonable suspicion standard embedded in the Fourth Amendment. Mr. Kleven was interrupted early and often, as is common practice in Supreme Court oral advocacy. Most of the early questions were posed by the more conservative faction of the Court. They probed Mr. Kleven with hypotheticals, trying to tease out the limits of his argument. From Chief Justice Roberts:

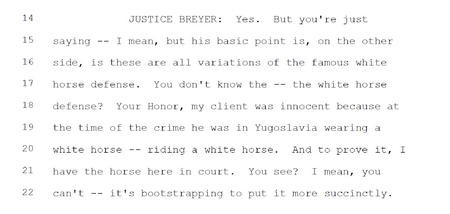

Justice Breyer, usually one of the most frequent (and witty) questioners during oral argument, must be biding his time, I thought. He became more active about halfway through the hour-long argument. He offered up the following at 1:33PM:

White horse defense? Criminal activity in the former Yugoslavia? Bootstrapping? I had no idea what Justice Breyer was talking about. I instinctively nodded in approval anyway. He must have caught the motion of my head in his peripheral vision. He turned right towards me, glanced for a split-second, and nodded in return. He quickly returned his gaze to the lawyer standing at the lectern and continued his questioning. I swiveled in my seat, looking around. Did any of the people sitting near me notice what had just occurred? None of my fellow attendees deviated from their stoic poker face.

I don’t remember much from the courtroom after that. A Supreme Court justice had just looked at me and nodded. I told several people about what had happened in the subsequent days. They all looked at me funny. No one else approvingly nodded like Justice Breyer. I am not sure why. It seemed noteworthy and interesting. I thought it might also provide some insight into how the case would be decided. Would Justice Breyer’s hybrid question/comment turn out to be revealing? Perhaps even dispositive?

The justices often take several months to render their written decisions after oral argument. Navarette v. California was decided on April 22, 2014 in a twenty-four page opinion. The 5–4 split was unusual. Justice Clarence Thomas, probably the Court’s most conservative jurist, authored the majority decision. Chief Justice Roberts, Justice Alito, and Justice Kennedy all joined Justice Thomas’s decision. No surprise there.

The fifth vote for the majority came from Justice Breyer.

Justice Scalia, whose votes often mirror those of Justice Thomas, penned a stinging dissent joined by Justices Ginsburg, Kagan, and Sotomayor. I scratched my head. I re-read the oral argument transcript. Were there any clues foreshadowing such an odd 5–4 split? I was frustrated, unable to reconcile the resolution of Navarette v. California with what had happened in the courtroom. Justice Breyer had looked at me and nodded, but the substance of his comment preceding our brief interaction was nowhere to be found in the opinion. Was it irrelevant? Dismissed by the others?

From Justice Thomas’s majority decision:

The decision made no mention of white horses, Yugoslavia, or bootstrapping. Justice Breyer’s thought-provoking question, which I had visibly approved of despite my ignorance of its meaning, was absent, completely scrubbed.

Justice Breyer looked at me and nodded at 1:33PM on January 21, 2014. The next time we have a fleeting intellectual connection, however, I probably won’t tell anyone about it.

Ryan M. Rodenberg is an assistant professor of forensic sports law analytics at Florida State University. The Supreme Court is, as of last Monday, back in session.

Intimate and Anonymous: Alejandro Cartagena's 'Carpoolers'

by Jon Michaud

The Art Museum of the Americas stands at the junction of Virginia Avenue and 18th Street in Washington, D.C., just a few blocks from the White House, the Washington Monument, and the Vietnam Veterans’ Memorial. The red-roofed Spanish colonial villa that houses the museum is a sort of in-law residence annexed to the palatial Organization of American States headquarters (also known as the Pan American Union Building), which occupies the 17th Street side of the same block. A well-tended public sculpture garden featuring the busts of pan-American statesmen and writers separates the two buildings. There are no fewer than four statues of Simón Bolívar on or near the grounds, as well as castings of Pablo Neruda, Abraham Lincoln, José Martí, Gabriela Mistral, José Cecilio del Valle, and Gabríel Garcia Marquez. Walking among those art works assembled in the name of inter-American unity and cooperation is a melancholy experience; such aspirations are so out of synch with the current political reality that I half-expected the plaques on the statues to be in Esperanto.

What brought me to the AMA was a show by the photographer Alejandro Cartagena, titled “Small Guide to Homeownership.” Cartagena, who was born in the Dominican Republic but lives and works in Mexico, certainly fits the pan-American mold. The exhibit begins humbly enough, with a looping black and white video of the entrance to a 2010 “real estate event” in Mexico: Potential home-owners wander in an out of a doorway marked “Buscando Casa” as music plays, depicting the banality of the consumerism that drives the continued expansion of the outer suburbs of Monterrey, Juarez, and Apodaca (not to mention Atlanta, Las Vegas, and Washington, D.C.).

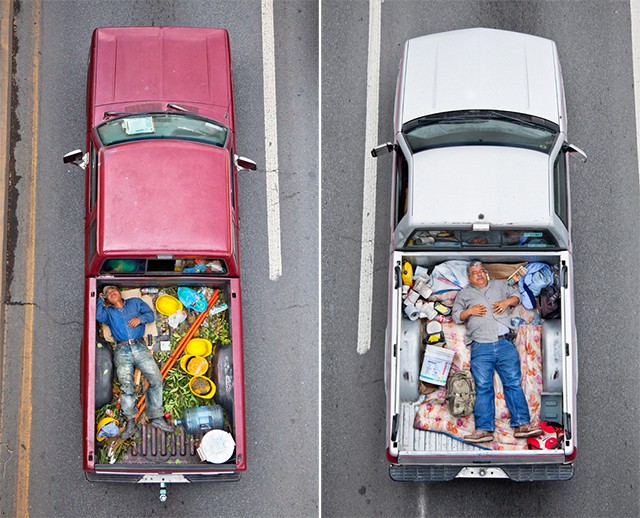

But all of that was prelude. Thirty startling images from Cartagena’s “Carpoolers” series, taken in 2011 and 2012, comprised the rest (and best) of the show. “Carpoolers” is a found poetry of terrific power: Twice a week, during the morning rush hour, he set his camera up on a pedestrian overpass above Highway 85 in Monterrey and took bird’s-eye-view images of day laborers in the backs of pickup trucks on their way to cut lawns, plaster walls, and excavate swimming pools in the city’s wealthy neighborhoods. Intimate yet impersonal, voyeuristic yet respectful, the photos offer glimpses at men who are usually overlooked or hidden from view. “I was very excited when I found these workers going to work this way,” Cartagena told me in an email. “I had been looking for a way to represent the people who had bought the small suburban houses and how they were managing going to work every day.”

All thirty photographs share the same composition: an overhead view of a truck. The truck appears to be driving vertically, up the wall of the museum. On either side, you can see the blacktop and the lines painted on the road. Sometimes a bare elbow pokes out of the passenger-side window. On the truck’s dashboard there are clipboards, folded newspapers, and plastic food containers. The vehicles are interchangeable for the most part, but the eye keeps getting drawn down to the rectangular pickup beds. In one photo, a young man lies on his back, arms folded across his stomach, his body parallel to a row of wooden beams. He looks as stiff as a piece of lumber, eyeballing the viewer suspiciously. In another, five young laborers lie crammed into the space like shipwreck survivors sleeping on a raft. A third shows two men reclined next to piles of cabinetry, staring up at the camera with smiles on their faces, as if they have just been caught plotting a practical joke. In several cases, the human passengers are not immediately identifiable; they are hidden under blankets or sheets of cardboard, just another piece of cargo sharing space with ladders, wheelbarrows, buckets, shovels, brooms, and rakes.

Stare at these pictures long enough and the truck beds and their contents will transform. Suddenly you are looking at a dumpster in which a dead body has been tossed; a potter’s grave sprinkled with lye; a bed in which one spouse sleeps contentedly while the other grumpily reads a newspaper; a social club with nearly a dozen men sitting in a circle talking companionably. In one of my favorites, the bed resembles a tropical salad: green, lettuce-like hedge trimmings, the carrot-colored orange poles of the landscaping tools, the upturned yellow hard hats like hollowed out mangoes. The prone, denim-clad workman is a splash of blueberry vinaigrette. In yet another, a man wrapped tightly in a colorful Mickey Mouse blanket could be either a sleeping, overgrown toddler or a mummy unearthed from the peat bogs of Ireland.

By excluding all context beyond the sides of the trucks, Cartagena’s photographs invite interpretation and speculation. Is traffic moving or not? How loud is it? Where are they going? We can only guess. The viewer begins to wonder about the social hierarchy among the men in these trucks. Is there a pecking order? Do they rotate who gets to sit in the comfort of the cab? Is banishment to the truck bed a form of bullying? Do some of the laborers prefer it so they can catch a nap? Cartagena’s pictures tread the line between the uncanny and the mundane, the private and the anonymous. He urges us to ponder the lives of people many of us would rather not think about.

The show at the AMA closed in September, but Cartagena has recently gathered a hundred and twenty-seven of his Carpool pictures into a book of the same name. The volume, which features many photographs that have never been exhibited before, can be purchased only through Cartagena’s site. “The book covers almost all the pictures I think of as the whole project,” Cartagena told me. “The construction of the book makes some of the images just work on a page and not on the wall.” The photographer, meanwhile, continues to work on his overall project of documenting the transformation of Mexico’s cities. His next series, he says, will examine the ways that the country’s rapidly expanding suburbs are transforming the existing infrastructure of its cities. It may sound like a lesson in urban planning, but “Carpoolers” gives us ample evidence that Cartagena will find a way to make this subject compelling and human.

After more than an hour in the exhibit, I walked back though the gardens to get a closer look at the Pan American Union Building. There, near the corner of 18th Street, I came across a team of landscapers who had spent the morning working on the grounds of the O.A.S. headquarters. Looking like they had stepped right out of Cartagena’s photographs, the men were taking their lunch break under a tree. Two were talking in Spanish and laughing. One was reading a newspaper. Another was sleeping. The fifth was thumbing nervously at his smartphone. Nearby, in the driveway, was their truck. I couldn’t help but notice that it had a double cab, large enough to accommodate all of them.

Jon Michaud is a novelist and blogger, and the former head librarian of the New Yorker. His most recent novel is When Tito Loved Clara.

Photos copyright Alejandro Cartagena. Used with permission. Carpoolers is available now.

Ex Hex, "Waterfall"

Most of the songs on Ex Hex’s Rips aren’t quite as short as “Waterfall” — the twelve tracks on the album, which has appeared on most of the streaming sites by now, clock at thirty-five minutes. But it’s a certainly a concise album, and in the best way: quick, full, never dense or rushed. It’s an album you can play a few times in a row before noticing that you’ve started over.