Intern Deluxe: The Rise of New Media Fellowships

by Eric Chiu

My first unpaid media internship was in the summer of 2010. Like most college students, previous semesters spent whiffing on applications made landing one feel like a reward, regardless of pay — I’d move to New York and even have the chance to write (mostly) professionally. The “unpaid” part always loomed, but my friends and I made it work through varying levels of cost-cutting and couch-crashing. Besides, we were all believers in that age-old internship axiom: As stressful as working for free was, we’d be getting the experience and exposure needed to compete for real, paid jobs. The problem with “climbing up to minimum wage” as an employment strategy never really crossed our minds.

Unpaid internships, long a due-paying rite of passage for college students, became entrenched as a stopgap solution for employers with spots to fill but without the money to properly fill them. This was (and is) very bad. In cases where full-time work was carried out under the auspices of internship programs, it was also illegal. And, as the ways that many unpaid internships violated labor laws became common knowledge, former interns began taking their employers to court. The earliest lawsuits, filed around late 2011, challenged the argument that interns weren’t technically employees and didn’t qualify for protections like minimum wage because they were getting educational or professional benefits by being in the office. After a federal judge ruled that Fox Searchlight Pictures was illegally using unpaid interns on the movie Black Swan in June 2013 — the first major ruling against unpaid internships — a wave of lawsuits followed against media companies like Conde Nast, NBC Universal and Gawker Media. (A similar case against the Hearst Corporation, filed in 2012, is currently under appeal.)

The media industry adapted swiftly: Slate began paying its interns in December 2013; Conde Nast shuttered its intern program entirely; and the Times ended its sub-minimum wage internships in March. But other high-profile employers have turned to a new way to temporarily employ students or recent grads: fellowships.

The term is certainly an improvement: Who would want to serve as an intern when they could work as a fellow? The concept is also pedigreed: Fellowships have existed in academia for a while — the Rhodes Scholarship, which started in 1902, purports to be the oldest international academic fellowship program. Traditionally, academic fellowships have been year-long scholarship programs with explicitly scholastic goals that rely on funding from private foundations or nonprofits. These fellows can travel the world or attend universities for research, grad school or work; it’s a far cry from a typical cubicle-dwelling first job. By comparison, most modern media fellowships fall somewhere between an internship and a full-time job, since a fellow gets paid and works just like a regular employee — except that they aren’t.

The Atlantic Media Fellowship Program, which started in 2009, was one of the first of its kind. Outlets including Buzzfeed, the Huffington Post and Wired launched their own fellowship programs between 2012 and 2013. (Though the current boom in fellowships occurred alongside the first round of unpaid internship lawsuits, its participants were largely anticipating, not reacting: Buzzfeed, the Huffington Post and Wired had previously paid interns.) The language of these fellowships gives some idea of what a new prototypical fellow does, and is: Buzzfeed’s fellowships will be “for the next generation of writers and editors eager to master the tools and techniques of the social web,” while Wired and Pacific Standard’s programs target candidates “pursuing journalism as a career” who’ve had “experience working in a deadline-oriented environment.”

Internally, employers make a point of emphasizing the distinction between fellows and interns, and between both and regular staffers. In Vice’s piece on interns at liberal publications, a Mother Jones spokesperson said that the magazine doesn’t consider its fellows and interns to be employees.1 In practice, these boundaries seem to be more fluid. Ample overlap frequently exists between internships and fellowships, which aren’t always meant to replace intern programs; both coexist within Huffington Post and Buzzfeed, for example. The following job listings from the Huffington Post and Buzzfeed share several bullet points — staffers are expected to pitch, write and follow a beat like any reporter — but the distinction is with each position’s title.

Huffington Post is asking for a fellow; Buzzfeed is looking for an intern. If it wasn’t stated explicitly, would you be able to tell the difference?

A fellow’s typical day-to-day schedule at many media organizations muddles the boundaries between interns, fellows and employees further. At Atlantic Media, fellows are usually recent college graduates who are brought on for a year and placed into a department within the company. (The Huffington Post also places fellows into areas besides editorial departments.) The self-defined nature of other corporate fellowships makes the taxonomy more difficult, but most start from a template similar to The Atlantic’s. For fellows at outlets like Gawker Media or Grist, responsibilities include fact-checking, researching or writing posts, and production, all on schedules similar to a full-time employee’s.

As with internships, compensation can vary widely. Vox Media pays its yearly data visualization fellows a thirty-five-thousand-dollar salary plus benefits, while Mother Jones provides its fellows an initial fifteen hundred dollar monthly stipend. Education is also a part of fellowship programs at Wired, the New York Times and Buzzfeed, which hold regular workshops and seminars for fellows. (There’s no apparent legal relevance to these classes, which are genuinely oriented toward professional development.)

Accordingly, current labor law considers corporate fellowships and internships to be essentially the same thing. The Department of Labor’s six-point internship test plays a role here; its questions determine educational intent and if a position can legally use unpaid workers.

- The internship, even though it includes actual operation of the facilities of the employer, is similar to training which would be given in an educational environment.

- The internship experience is for the benefit of the intern.

- The intern does not displace regular employees, but works under close supervision of existing staff.

- The employer that provides the training derives no immediate advantage from the activities of the intern; and on occasion its operations may actually be impeded.

- The intern is not necessarily entitled to a job at the conclusion of the internship.

- The employer and the intern understand that the intern is not entitled to wages for the time spent in the internship.

According to the Department of Labor, jobs that fail any part of the test “will most often be viewed as employment” and would require workers to be given additional benefits.

In an email, Department of Labor spokesman Jason Surbey said that the organization doesn’t distinguish between internships and fellowships when considering the Fair Labor Standards Act (FLSA) and the six-point test. The law doesn’t care. “Whatever you call it — whether it’s an internship or a fellowship — it doesn’t matter what the label is,” Cheylynn Hayman, an attorney at Utah law firm Parr, Brown, Gee & Loveless specializing in employment litigation, told me. “The question is: what substantive work is the person performing and why and what advantage is the company deriving from that person?”

The law considers the distinction semantic, the same isn’t necessarily true of employers, or of applicants. Rebranding has causes. It also has effects. Certainly, some high-profile fellowships have unique advantages compared to internships. According to the coordinators we spoke to at outlets including Buzzfeed, Huffington Post and Atlantic Media, corporate fellows tend to be college seniors, recent grads or graduate students. Finding future employees is an implicit goal for these programs. Huffington Post fellows have responsibilities designed to be like a junior editor’s, ranging from story-pitching to managing social media accounts. Full-time offers are not an assumed long shot. According to Emily Lenzner, vice president of global communications at Atlantic Media, sixteen of the thirty-eight fellows in the company’s 2013–2014 fellows class were hired as full-time staffers. Buzzfeed fellows have also been hired as editors and staffers in various verticals.

If this is the new status quo — cheap but not free labor for media companies, low but real pay for fellows, a nontrivial chance at employment — it’s an upgrade. It’s also important to imagine what kinds of temptations it could create for employers — and workers — in the long term. The modern history of media internships is instructive: As the baseline expectation for internships gradually increased — a 1997 Baffler article imagines a future where you’d “need at least a semester or even a year” of internship experience in order to compete for desirable positions — large, cheap (or free) internship programs were allowed to flourish. In the process, they didn’t stop serving their purposes as training programs, or sources of future employees. They just did so at greater and greater cost to the young workers who participated them — the same workers who needed them more than ever.

Peter Sterne is a media reporter at Capital New York who also runs Who Pays Interns, a site that tracks pay rates for media interns and fellows. For someone searching for a media job today, he says, multiple semesters worth of experience feel like a prerequisite. “At one time, companies would’ve hired people and then trained them,” Sterne said. “Increasingly, these days, it seems that you’re expected to already have skills built up through unpaid internships and maybe a fellowship, and then you get hired based on that.”

Getting paid as an intern or fellow certainly helps, but against the raging garbage fire that is employment prospects for recent grads or students, it’s a partial solution. In February, Buzzfeed’s Doree Shafrir — responding to a New York Times piece about college-aged interns unable to find jobs — proposed a way to solve the problem of permainterns.2 While Shafrir acknowledges that jobs in industries like journalism were never easy to come by, she argues that the market for internships needs to more accurately reflect hiring prospects:

“So now the onus has shifted to people like me, who are hiring them and managing them — and, I think, collectively failing them. When we get internship applications from people who have had three, four, five, or more internships in our field, with no full-time job on their résumé, it is kinder for us to reject them than perpetuate the hope that they might one day break through… I think the solution to this is to reduce the number of internships we’re offering in the first place, pay all of our interns, be more selective about the interns we do hire, and limit the term of an internship to no more than four months… Those of us who are hiring interns should only be hiring people whom we feel we could potentially hire as full-time employees, and we should only hire as many interns as we can have performing meaningful work — work that will help them get hired one day.”

This outlook changes, materially, what an internship is. It also makes clear what it still isn’t: an entry-level job.

Even in a competitive field like media, there at least used to be a coherent farm system for college grads looking for a job. You could start off at a smaller alt-weekly or newspaper and get experience as a staff writer, along with a full-time paycheck. With a staff job, there’s less worrying about where you’ll be, how you pay your bills, and whether you can afford anything much better than catastrophic medical insurance. With these training structures either gutted or burned to the ground, permainterning appeared as a replacement, albeit an inadequate one. The question, then: Are fellowships simply pulling internships up? Or will they eventually pull what’s left of the entry-level jobs down into contract-work limbo?

The novelty of new fellowship programs illustrates just how totally the expected value of these types of short-term positions, from a job-hunter’s perspective, has depreciated. At one time, a college degree and a short successful stint of professional experience might have bumped you to the level of “competitive applicant.” Now, if you’re lucky, it will get you what amounts to a three-month tryout at a company like AOL. You might get the job. You might not. This, you will think, is fine: You received a few months’ pay and a new line item on your resume. And besides, at least it’s not five years ago.

1. While it might seem like a nonissue, the different titles can have potential ripple effects elsewhere.

2. Referring to recent college grads who hop from one internship to another.

Eric Chiu hasn’t been an intern for nearly a year.

We Chased Another Woman Off Twitter, Good Job Everyone

@chrissyteigen twitter is a double edged sword. You can tweet jokes that aren’t jokes and other people can tweet what they want as well.

— Adrian Arriaga (@aidansdaddy619) October 23, 2014

Utah-born writer and model Christine Teigen (also the spouse of John Legend) is leading the way off Twitter because you’re all really stupid, possibly illiterate, and have no impulse control. We encourage you to follow her. No not “follow” her on social media. Follow her off social media. Oh yes, her evil crime?

active shooting in Canada, or as we call it in america, wednesday

— christine teigen (@chrissyteigen) October 22, 2014

Uh huh? Accurate. Anyway, she gave it a good college try, engaging with enraged loons for as long as possible. This was particularly deft:

Wait so now I’ll seem smarter in a swimsuit god this is confusing RT @jeg_28 Stick with the swimsuits. You’ll seem smarter.

— christine teigen (@chrissyteigen) October 22, 2014

But we all know how this story ends: with a stupid “balanced” write-up in a newspaper. Sad times!

Everything Except Rap and Country

There is something that reviewers are not quite saying about Taylor Swift’s new album, 1989. It’s on the tips of their tongues. Jon Caramanica comes closest:

Modern pop stars — white pop stars, that is — mainly get there by emulating black music. Think of Miley Cyrus, Justin Timberlake, Justin Bieber. In the current ecosystem, Katy Perry is probably the pop star least reliant on hip-hop and R&B; to make her sound, but her biggest recent hit featured the rapper Juicy J; she’s not immune.

Ms. Swift, though, is having none of that; what she doesn’t do on this album is as important as what she does. There is no production by Diplo or Mike Will Made-It here, no guest verse by Drake or Pitbull. Her idea of pop music harks back to a period — the mid-1980s — when pop was less overtly hybrid. That choice allows her to stake out popular turf without having to keep up with the latest microtrends, and without being accused of cultural appropriation.

That Ms. Swift wants to be left out of those debates was clear in the video for this album’s first single, the spry “Shake It Off,” in which she surrounds herself with all sorts of hip-hop dancers and bumbles all the moves. Later in the video, she surrounds herself with regular folks, and they all shimmy un-self-consciously, not trying to be cool.

See what Ms. Swift did there? The singer most likely to sell the most copies of any album this year has written herself a narrative in which she’s still the outsider. She is the butterfingers in a group of experts, the approachable one in a sea of high post, the small-town girl learning to navigate the big city.

The line on the new album’s music is: Less country, more pop. But not just any pop! Maybe…white pop.

This would complete every thought:

[Katie Perry’s] biggest recent hit featured the rapper Juicy J; she’s not immune.

Immune to… non-white influence?

[Swift’s] idea of pop music harks back to a period — the mid-1980s — when pop was less overtly hybrid.

And, in the same quarters, more overtly white!

That choice allows her to stake out popular turf without having to keep up with the latest microtrends, and without being accused of cultural appropriation.

Avoiding non-white “microtrends” isolates Taylor Swift from charges of appropriation, because they have no specific and recent non-white influence to refer to.

[In “Shake It Off”] she surrounds herself with all sorts of hip-hop dancers and bumbles all the moves. Later in the video, she surrounds herself with regular folks, and they all shimmy un-self-consciously, not trying to be cool.

Who, exactly, would interpret those signals as not “cool” but instead “regular?” Not everybody; specifically, somebody.

The singer most likely to sell the most copies of any album this year has written herself a narrative in which she’s still the outsider.

You know who else suddenly feels culturally outside of the mainstream? (Besides, as always, anyone over the age of 30?) People who are skeptical of America’s demographic progress! Or who, at least, don’t feel comfortable thinking or talking about it. If Jon Caramanica is right, the promotional theory and marketing conversations around 1989, and an overarching influence on its music, can be summed up as: Intentional, Performed Whiteness. It’s an artistic manifestation of the old adolescent conversation:

“What kind of music do you like?”

“Everything. Except rap and country.”

Bing & Ruth, "The Towns We Love Is Our Town"

As everything becomes progressively more terrible and the pace of the progression accelerates at a clip that, each time I notice it, seems even more aggressive and unlikely when compared with the speed at which the previous increase in awfulness occurred, it seems that the few new things in which I find comfort are those which reduce or eschew altogether the use of words. Words are terrible. Our only hope is in everyone shutting up. The future is wordless sound. Listen to this. [Via]

Unrelenting Trauma: It's a Living

“So companies like Facebook and Twitter rely on an army of workers employed to soak up the worst of humanity in order to protect the rest of us. And there are legions of them — a vast, invisible pool of human labor. Hemanshu Nigam, the former chief security officer of MySpace who now runs online safety consultancy SSP Blue, estimates that the number of content moderators scrubbing the world’s social media sites, mobile apps, and cloud storage services runs to “well over 100,000” — that is, about twice the total head count of Google and nearly 14 times that of Facebook.”

Mood Disrupted

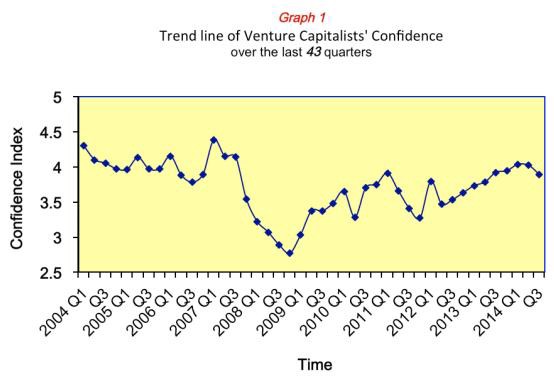

Each quarter a gaggle of Bay Area venture capitalists are asked, you know, how does everything feel? Aside from totally great, of course. What’s your sense of things, other than that you are changing the world utterly for the better?

This quarter’s index measurement fell [to 3.89] from the previous quarter’s index reading of 4.02. The Q3 reading is the first recorded decline in confidence in two years.

In the new report Professor Cannice indicates that “The lower Q3 index reading raises some concern for the near to medium term outlook for the high-growth venture environment.”

The concept of Valley investor “confidence” is unusual. In a survey context, confidence is usually something that respondents have in outside entities: in a government, in an economy in general, in markets that are subject to a wide variety of outside forces. But here, the question seems almost circular. The respondents are asked how confident they are in “the future high-growth entrepreneurial environment,” the growth of which is, when things are going well, disproportionately contingent on venture capitalists’ confidence. A very confident venture capitalist is a venture capitalist who can say, “I have a shot at turning this company, which makes no money, into a billion-dollar acquisition target for one of a small handful of large flush companies,” or, much less often, “I think one of my very savvy early investments might be able to go public soon.” There are factors that they cannot control, which might make them less confident; if just one giant tech company slows down its spending, hundreds of startups’ prospects suddenly get dimmer. But the way investors respond, here, does not suggest they are too concerned about that, at least for now. They seem to be more concerned with talk. “The ‘bubble’ talk has grown louder, especially discussion about high valuations and burn rates,” says one investor (this despite “rampant disruptive innovation,” the report later adds). His answer to the question about confidence, in other words, is to note that, while everything is great, some other people sound less confident, talking about “burn rates” and “revenue” for reasons that he cannot fathom and which are certainly not at all strategic, and none of this makes any sense to him, because the fundamentals are just so strong, but there you have it, there’s been some talk, oh well. It’s the confident leading the confident, in Silicon Valley! Which, counter-intuitively, is why this metric actually might mean something.

New York City, October 21, 2014

★★ Purple sheets of dawn clouds went away, and gray, white, and blue vied for the skies. Humidity, chill, and brightness were in a marine or tropical-feeling imbalance: a little uncomfortable, a little comfortable, but only provisionally so either way. The sun ceded its share, then reclaimed it and more. Clouds gathered in the late west, edges rumpled and glowing like an illustration of gates to the mansions of paradise. Then the sun went lower and the mass of cloud was dark and grim. Later, in full night, light pollution cast bright auras on the low clouds as lightning glimmered and flared and eventually flashed. A hissing downpour arrived, and the patterns of light fuzzed away.

A Brief Conversation with the Internet Concerning Renée Zellweger

Here Are Some Pictures of Renée Zellweger

but

Here is Renée Zellweger’s Awesome Response To Trolls Over Her Appearance

however, this is

What’s Really Behind The Ridicule Of Renée Zellweger’s Face

and actually

If You Looked at Renee Zellweger’s Plastic Surgery, You Need to See These Photos

which will remind you that people are dying, specifically of Ebola, despite the fact that

This Ohio man has the perfect reaction to Ebola

and anyway

Don’t panic over Ebola in America

that said, consider

The Dangerous Myth of America’s Ebola Panic

because

“Americans were far more likely to believe in witches than to worry about contracting Ebola”

which doesn’t matter if you understand the real

Threats to Americans, ranked (by actual threat instead of media hype)

and that you should

because

It’s soda that should terrify you

because

Drinking soda regularly can age the body just as much as smoking regularly

although

and also

because

The Effects of Childhood Obesity on Adolescent Health are Much Worse Than We Thought

except

Think You Know What ‘Fat’ Means? You Should Listen To This Dude’s Definition.

although

When You Hear Someone Say ‘Fat,’ They Have No Idea What They’re Talking About

and yet

The U.S. Is Still No. 1 in the World — Just Not in a Category We Should Celebrate

except

Look At All The Ways Pop Culture Discriminates Against A Certain Body Type. How Wrong Is That?

and

Science Finds One Physical Feature We Should Stop Judging Each Other On

because

Our Own Standard For Ideal Beauty Eliminates Us All

and

Renee Zellweger’s Fine, But We Need Some Work

because

In this Sunday's forthcoming New York Times Magazine -- which has been magically sent backward in...

In this Sunday’s forthcoming New York Times Magazine — which has been magically sent backward in time, from the future, to the internet of today — I have a short piece on how dynamic, demand-based pricing is probably going to become a staple of supremely popular restaurants as logistics-driven startups, of a piece with Uber and Airbnb, begin looking to disrupt (lol) woefully inefficient restaurant seating systems. In summary: Hope you like eating out on Tuesdays at 9PM. Unless you are rich, then why are you worrying about this, or anything at all? It’ll be just fine. You’ll be just fine. Everything’s fine.

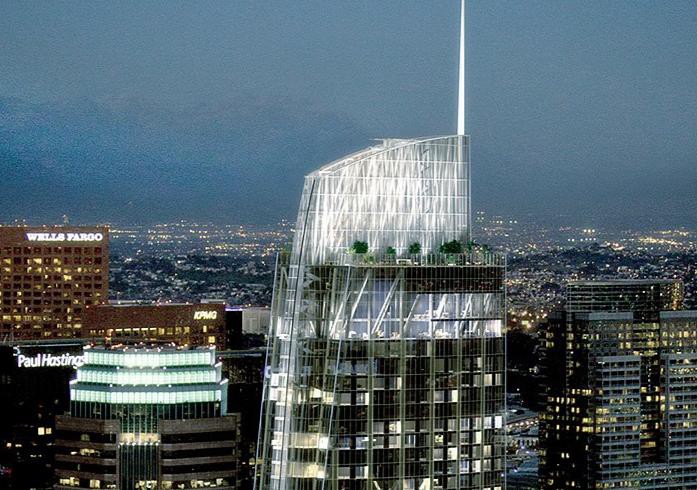

The Tall, Skinny, Shining Skyline That L.A. Deserves

For the last forty years, an odd rule from the Los Angeles Fire Department, known as Regulation 10, has required that every skyscraper in the city have a helipad for potential emergency rescues. This is why, architects argue, Los Angeles has a thoroughly medicore skyline. Here are a whole lot of them complaining to the New York Times about Regulation 10:

“The helipad regulation has hindered L.A. from having an iconic, memorable skyline in a city that desperately needs a stronger urban identity,” said Brigham Yen, a downtown realtor who writes a blog, DTLA Rising. “Downtown L.A. now has the opportunity to design visually stunning high-rises with spires that will strengthen its position as an urban center.”

Brenda A. Levin, a Los Angeles architect who has overseen renovations of some of the city’s most historic buildings, said that the restrictions had served only to encourage “mundane architecture.”

Requirement 10 was “an antiquated idea, and it stunts the architecture in a city that is known for design,” said Christopher C. Martin, the tower’s chief architect. “Can you imagine the Academy Awards if all the actors came out and said, in all L.A., we should have flattop haircuts?”

“In tall buildings, all the brush strokes should go up,” Mr. Martin added. “You should accentuate the height. To truncate the top is not attractive.”

Professor Woo said that while some people “dismiss it as only an aesthetic concern,” it was more than that. “That skyline is really crucial to the identity of the city,” he said. “People outside of here don’t realize this has been going on for 40 years — architects adjusted to it.”

Last month, the fire department agreed to drop the rule. This, the architects predictably predict, will allow a thousand spires to bloom, finally giving Los Angeles the cool, extremely distinct skyline that its residents deserve, so they no longer have to concede that point when they’re accosted by someone from New York.

And yet. The building that most immediately led to the re-examination of Regulation 10, the forthcoming the Wilshire Grand Center, the tallest building west of the Mississippi River, with its angular, sloping roof and giant spire, is distinct only in that it looks like it could belong in any random city but Los Angeles; it could just as easily be just another supertall spire shooting up in midtown New York City, another point anonymously poking the sky in the pointy skylines Shanghai or Hong Kong.

The flat top was the Los Angeles hallmark, and a squandered opportunity for distinction and unusual architecture; the spire is an invitation to ascend toward a different kind of bland, gleaming sameness, toward false heights and largely unremarkable stunt architecture. But maybe that suits LA just fine.