New York City, November 9, 2014

★★★★ Thin wooly high clouds, flowing from south to north, gave way to combed-out wisps, which gave way in turn to smooth translucent sheets. The crushing cold had lifted, but the temperature bounced back a decisive increment lower than it had been. The leaves were thinned a bit on Broadway now. The light thinned too, for a while, as the cloud sheets did their work. Then the clouds evolved again, into distinct tufts, still flowing upstream. The glass face of the wine bar was closed against the chill. A dusk-minded shade held the playground; even so, it was full, the parents and children having adjusted to the diminished ration of warmth and light. The slides were clogged with traffic, much of it going up. Light shone from the open restroom door like something in a sentimental and cozy painting. The clouds grew shiny, and then pinkened. A pink glow from the lower sky flowed between the buildings, then was picked up and amplified by the sodium lights coming on. Shoe lights flickered brighter and brighter. The three-year-old lurked with a stick-gun in the twilight, taking tactical advantage against invisible foes.

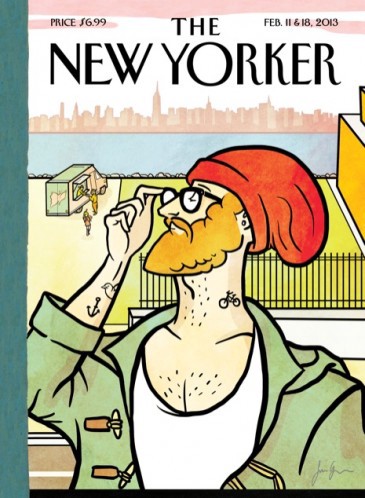

A Paywall Rises

We are quite reliably told that tomorrow, the Web site of the New Yorker, the last magazine in the world, will no longer offer the entirety of its archives, going back to 2007, for free. A metered paywall, using blueprints from the New York Times and the Financial Times, has been constructed; the plan is for it it to be erected at around eight in the morning. Once in place, it will allow unsubscribed readers to access just six articles per month for free. Then it will ask them to pay up.

The New Yorker’s paywall is both inevitable and eminently reasonable; it’s hard to imagine it being controversial for any reason other than its abruptness, though it was always clear that a paywall was coming, eventually. (And what some might see as interesting quirk of the paywall architecture, that a short blog post is weighed the same as a sixteen-thousand-word profile of the president, is ultimately a net good: As a value system, it incentivizes the magazine to make every piece equally excellent, since they all count the same for readers.)

Reporting and writing and editing (and offices in the World Trade Center) are all very expensive. Someone has to pay for it, and advertising alone, even in an era when the New Yorker can hope for an exponentially larger audience than it has ever had, cannot yet, if ever, cover that bill. So it must fall to readers. And if there is a magazine that is worth paying for, it’s probably the New Yorker.

Here is a list of things you might want to read before tomorrow morning if you’re too terrible of a person to subscribe (and, come on, it’s like a dollar a week.)

The Semantic Death of Net Neutrality

Political language is garbage. No, that’s wrong: American Politics is the garbage, and its language is just the stink. “Pro-life” and “pro-choice” do not look each other in the eye. “Pro-family” activists oppose the legal establishment of many particular families. The absence of a “right-to-work” law does not eliminate any right to work, real or imagined.

This falls into a certain class of problem, which I guess you could call toxic semantic byproduct. An empty corporate culture gives way to hollow office speak; an identity-confused media gives rise to CONTENT without content; an entrenched contract-based wireless industry allows misleading advertising nonsense to be passed off as bold straight-talk. In isolation, these byproducts would all rise to the level of problems worth addressing. In the shadows of their much larger and more insidious root problems, it seems beside the point to bring them up.

But here were are, on the cusp of an national conversation about net neutrality, with a special case: An issue that’s important but not an immediate threat to human wellbeing; a corresponding language so horribly mangled and confusing that it precludes productive public debate. Net neutrality is the rare political discussion with a semantic byproduct so toxic that it doesn’t just drive away people who might want to engage with it, it risks suffocating itself. Try working backwards from the President’s announcement today:

An open Internet is essential to the American economy, and increasingly to our very way of life. By lowering the cost of launching a new idea, igniting new political movements, and bringing communities closer together, it has been one of the most significant democratizing influences the world has ever known.

“Net neutrality” has been built into the fabric of the Internet since its creation — but it is also a principle that we cannot take for granted. We cannot allow Internet service providers (ISPs) to restrict the best access or to pick winners and losers in the online marketplace for services and ideas. That is why today, I am asking the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) to answer the call of almost 4 million public comments, and implement the strongest possible rules to protect net neutrality.

By the time he gets around to defining net neutrality, in four bullet points, it’s too late: the feeling that you are being sold on something, not told about it, is overwhelming from the start. What you’re being sold, however, is not.

Now try this sympathetic response from Tim Wu, the man who coined the term “net neutrality,” published on the New Yorker’s website:

In 2007, then Presidential candidate Barack Obama pledged that he’d only appoint Federal Communications Commission chairmen who support net neutrality — the rules that forbid broadband companies from blocking certain Internet traffic or creating slow lanes so that some Web sites run faster than others. He called himself “a strong supporter of net neutrality,” and that helped him to win the support of many people in the technology world. But things didn’t go as planned…

…With another compromise looming, the President today released a video that suggests, in short, that he’s had it. In unusually explicit terms, he has told the agency exactly what it should do. Enough with the preëmptive compromises, the efforts to appease the carriers, and other forms of wiggle and wobble. Instead, the President said, enact a clear, bright-line ban on slow lanes, and fire up the agency’s strongest legal authority, Title II of the 1934 Communications Act, the “main guns” of the battleship F.C.C.

In an interview last month, Wu said he doesn’t regret coining the term: “People say it’s confusing and yet somehow millions of Americans found themselves motivated to write to the [Federal Communications] Commission.” The first mention of net neutrality in his piece is followed by an attempt at definition that falls back on a metaphor about roads and lanes and traffic. If Wu can’t easily cut to the essence of net neutrality, who can?

Netflix responded with its own positive formulation, which the White House Twitter account then retweeted:

Pres. @BarackObama agrees: consumers should pick winners and losers on the Internet, not broadband gatekeepers. http://t.co/5PQdm7hiOo

— Netflix US (@netflix) November 10, 2014

There’s a lot going on here. If net neutrality is about “lowering the cost of launching a new idea,” why does Netflix care? They’re an incumbent company! Is it because net neutrality rules could conceivably save the company a lot of money, or prevent it from losing a lot of customers? Yes, obviously, which makes the Twitter endorsement.. I don’t know, sort of weird, as a point in favor of new government regulations? To be fair, “Netflix wants net neutrality, and you like Netflix” is one of the clearest arguments the White House has at its disposal right now.

If you were to try to find Comcast’s position on net neutrality, there’s a good chance you would end up on its official net neutrality page, which contains this paragraph:

Net Neutrality Protection for More Americans: Comcast’s transaction with Time Warner Cable will bring Net Neutrality protection to millions of new customers in cities from New York to Los Angeles. A free and open Internet stimulates competition, promotes innovation, fosters job creation, and drives business.

This was updated four days ago. Today, the company issued this statement:

Comcast fully embraces the open Internet principles that the President and the Chairman of the FCC have espoused — transparency, no blocking, non-discrimination rules, and no “fast lanes”, which is the way we operate our network today.

But:

We continue to believe… that section 706 provides more than ample authority to impose those rules, as the DC Circuit made clear.

So: Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet. However, also, but: Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet.

AT&T; was more direct:

Today’s announcement by the White House, if acted upon by the FCC, would be a mistake that will do tremendous harm to the Internet and to U.S. national interests.

The carriers’ political allies are anti-regulation conservatives. Thousands of people who already understand the contours of the net neutrality debate are pointing at this Ted Cruz tweet, suggesting that it is ridiculous.

“Net Neutrality” is Obamacare for the Internet; the Internet should not operate at the speed of government.

— Senator Ted Cruz (@SenTedCruz) November 10, 2014

And it is. He is. But if it’s more ridiculous than any of today’s other visible attempts at articulating what net neutrality is about, it’s difficult to say why. He may be wrongheaded, or just wrong, but putting this discussion into the terms of the healthcare debate — itself a toxic and indirect rhetorical nightmare — might actually be an improvement over what we’ve been doing for the last ten years. It’s wouldn’t be helpful, exactly, but it might be less unhelpful.

In practical terms, “net neutrality” is the idea that there ought to be laws that prevent the large, monopolistic companies that sell internet access from charging different rates for different parts of the internet, either by asking customers to pay extra to access, say, YouTube, or by asking YouTube/Google to pay some sort of fee itself. Opponents say that preventing internet providers from levying these fees would discourage them from investing money in infrastructure. They would make less, and so they would spend less, and so, the argument goes, progress would be stalled.

In philosophical terms, though, this a fight about whether or not the government should be allowed to regulate commerce — it’s a subset of an argument that American politics will do almost anything to avoid dealing with head-on, because it’s old and paralyzing and over before it even starts. A discussion about healthcare can survive such a diversion, barely, because the stakes are immediate and obvious — arguments about life and death have, at least, a sliver of a chance at transcending politics. Net neutrality is not that kind of issue. People don’t want to pay more for Netflix and hate their cable companies and already feel like their phone bills are too high. These are the proxy discussions available to net neutrality supporters: negatively defined, already exhausting, and theoretical, a lot like the phrase “net neutrality” itself. It’s a noble campaign to treat internet companies like electricity companies, not because people love ConEd, or because utilities operate perfectly, but because the alternative scenarios are worse. (One way to reframe and humanize net neutrality would be to make it about poverty, access, and inequality — to make the case that, without it, the poor would be exiled to a lesser internet. I WOULD NOT BET ON THIS APPROACH.)

The broken language of net neutrality has relegated it to a simmering background issue, difficult for politicians to deploy in the service of reelection, briefly breaking through only when the John Oliver makes a video, or a lawyer for Verizon says something egregious, or Barack Obama issues a statement out of the blue. The rest of the time it belongs to activists, who know what they mean but can’t quite get it across, and to lobbyists, who mean only to win.

The Twilight of the Indoor Mall

by Mike Nagel

On Memorial Day weekend, one of the bigger shopping weekends of the year, I stopped by the Collin Creek Mall in Plano, a Dallas suburb. Sitting back about a quarter mile from the highway, the mall has a hundred and thirty stores, over six thousand parking spaces, and more than a million square feet of retail space. It is faceless, sprawling, silent; the exterior walls are fading beige brick. On the day that I visited, it looked like it was going to rain. A security guard in a golf cart endlessly looped the parking lot, which was nearly empty. I was here to see if the rumors, press reports, and Yelp reviews were true: that the mall was dying.

Pharrell’s “Happy” played over the hi-fi inside the mall. It echoed down the hallways, bouncing off the walls and overlapping with itself in weird, dissonant ways without the plush, shuffling bodies of shoppers to absorb some of the sound waves. There was almost nobody here. A woman with a clipboard asked me to answer a few questions: When’s the last time I purchased sunscreen? Bought athletic footwear? Went swimming? I answered her questions, but kept walking as she half-chased me down the hallway; there were twenty-five yards between us when she asked how old I am. I told her that I am twenty-six, and then realized why she was so persistent: There were around a hundred people in the mall, and at twenty-six, I was one of the youngest. The old people were everywhere: walking laps and playing cards and sitting on benches and staring off into space. None of them had a shopping bag.

I first talked to the guy who worked at the sunglasses stand just outside the food court. He looked about thirty years old. His hair was bleached, dyed purple, and cut at a slant, a style that I hadn’t seen since the early aughts. At first, he didn’t hear me; he was playing Angry Birds on his phone.

“Dude,” I said. “What’s going on with the mall?”

“The mall?” he said. He puts down his phone. “The mall.” He looked around. “The mall is dead, man.”

“Dead right now? Or like, dead for good?”

“Oh Christ,” he said. “I hope it’s not dead for good. Did you hear it was dead for good? I heard management’s got something up their sleeves.”

“Like what?”

He looked around to see if anyone was listening.

“A movie theater,” he said.

I walked further into the mall, looking for someone who could explain what was happening to the mall I had been coming to since I was a teenager. When I talked to a woman at “Sassy Diva,” I was the only person in the store. The woman, who seemed maybe fifty years old, unfurled a map with a top-down view of the mall and started crossing out stores that had closed after Dillard’s abandoned its space; they had names like “Glitter” and “Hi-Kick.” She drew a shaky circle around a blank, blue square in the top right corner of the map. “This is the dead zone now,” she said. “I don’t know how long stores in that area are going to last.”

“How long do you think your store is going to last?” I asked.

“I’m not worried,” she said. “As long as Forever 21 is here, we’ll be OK.” She threw her head to the left. The Forever 21 was filled with teenage girls and bargain bins.

“Have you heard rumors about a movie theater?” I asked.

“Oh yes,” she said. “Everyone has.”

“Where’d you hear that from?”

She pointed to the salon across the way. “But don’t tell her I told you,” she said.

The salon was empty too. There were a dozen hair-cutting stations but only a single employee — the owner, who sat at the front desk. Her face drooped slightly when she talked, making her mood impossible to read. She told me that she’s worked in Collin Creek Mall since 2003. Back then, she had trouble finding places to park.

“Now look at it,” she said. “Saturday night. No one here.”

I asked her where the people have gone.

“Better malls,” she said. “Stonebriar, Watters Creek, Firewheel. Why would anyone come here?”

In the nineteen fifties, people with money began leaving the cities in unprecedented numbers. They were getting married, getting jobs, starting families, and buying houses — they were moving to the suburbs. A Time Magazine article in 1954 observed: “…since 1940, almost half of the 28 million national population increase has taken place in residential suburban areas, anywhere from ten to 40 miles away from traditional big-city shopping centers. Thus, to win the new customers’ dollars, merchants will have to follow the flight to the suburbs.”

They did, and the suburban shopping mall was born.

But the original idea for the mall was not just about retail. Victor Gruen, the father of the suburban shopping mall, envisioned something much bigger. He wanted outdoor areas, banks, post offices, and supermarkets; he wanted to give the suburbs a soul, one inspired by the public squares of European cities. But that never happened. Instead malls were faceless, sprawling. Gruen was so disappointed with what malls became, he gave a speech in 1978 in which he said, “I refuse to pay alimony for those bastard developments.” Malls turned out to be the very monoliths of soullessness that Gruen had tried to overcome.

It’s not just that there are better malls than Collin Creek in the Dallas area. It’s that there are so many malls; Dallas has more shopping centers per capita than any other city in the United States. And according to some estimates, fifty percent of indoor malls nationwide will die over the next two decades — partly because some shoppers are opting for newer, better malls, but also because, as a recent Guardian article put it, “the middle class that once supported” mid-market malls is dwindling. Or, put yet another way, by retail consultant Howard Davidowitz: “What’s going on is the customers don’t have the fucking money.” Which, of course, wasn’t always the case.

As these old malls die off, they’re being replaced more and more by upscale, outdoor shopping centers — with lofts, grocery stores, offices, public meeting areas, and day cares. At least four have popped up in Dallas within the past ten years, and they’re always packed. Sixty years after Gruen’s ideas were bastardized by short-sighted developers, they are finally seeing their day. Inklings, maybe, of the suburbs finding their soul.

It took more than a week for someone at the Collin Creek Mall PR office to call me back after I had left a message asking if the mall was going to die. Matthew, an employee at a PR firm called Integrated Corporate Relations, the firm that represents Rouse Properties, which owns Collin Creek Mall, called me from Boston. I told him that I was in Collin Creek Mall over Memorial Day weekend and that it was pretty dead; I told him about the empty parking lots, the abandoned spaces, the old people walking in circles, and the dead zone. He thanked me for my interest in the mall.

“Rouse Properties is absolutely committed to creating a great mall experience that meets the ever-changing needs of the community,” he said, reciting the copy from the Collin Creek Mall website. “Collin Creek Mall is no different. We will certainly take your concerns into account.” When I asked him if Collin Creek Mall is going to close, he told me that he has no news to share on that front. I asked him if other Rouse Properties malls are struggling right now too; he said that was not information he was at liberty to share. “Are there any other questions I can answer for you?” he asked. I told him no, and thanked him for calling me back.

“Wait,” I said, just before he hung up. “I do have one last question. How are the plans coming for the movie theater?”

There was a pause.

“I have no news to share about that,” he said.

“Are there plans to build a movie theater?” I asked.

Another pause.

“I am not aware of there being any plans to build a movie theater,” he said.

“What’s the plan then?”

“I have no news to share about any plans.”

Here’s what happens when a mall like Collin Creek Mall dies. After its first major anchor pulls out, stores around it continue to close, slowly but persistently, one at a time, year after year. The remaining stores rearrange, consolidate space, move closer to the entrances. The mall becomes depressing, yes, but it’s still viable. Eventually, though, another anchor decides to pull out. Maybe it’s Macy’s. Maybe it’s JC Penny. Another cavity forms, another dead zone. Foot traffic gets ligher. Management doesn’t tell anybody anything about the future of the mall, because management won’t tell anybody anything until the day they decide to close the mall for good. Stores hear rumors from other stores. Basic upkeep starts to slip. The floors get dirty. The plants die. The mall starts to smell. When two anchors leave, “that’s typically the beginning of the downward spiral leading to ultimate extinction,” Cedric Lanchance, director at a real estate analytics firm, said in a Business Insider article. “Most struggling malls don’t go down without a long, drawn-out fight, however — the evidence of which exists in hundreds of communities across the country where vacant wings of various shopping centers are beginning to crumble and decay.”

It could take years for the management company to finally call it quits, but eventually it won’t have a choice. A final date is announced. Summer sales become liquidation sales. Liquidation sales become closing sales. The last few remaining tenants are asked to leave, but most will stay open until the final day, selling not just remnant merchandise but pieces of the store. Local retailers will cannibalize the remains. Sections of the mall will be roped off. Mall walkers continue puttering around until the last possible moment. They walk laps in shorts and tennis shoes and neon pink visors. People show up with cameras. They post walkthrough videos on YouTube; they’re rarely sympathetic. Then, one day, the mall will close. Its doors will be locked and blacked out and no one will be allowed inside. That’s when the real decay will begin. Leaks form in the celling. Water gets in through the tiles. Mold spreads. Shattered glass from looters covers the floor. The ceiling caves in. Insulation hangs down, pink and poisonous. Displays that no one bothered to disassemble rot and crumble. The concierge kiosk collapses. Indoor plants that happen to have been planted beneath skylights continue to grow, outgrow their planters, crawl out onto the floor, creep through the mall.

The damage might not stop there. “When a mall closes, unemployment rolls in the region swell, and the loss of property, sales, and business taxes can leave municipalities with serious shortfalls,” The Week notes. “The city of North Randall, Ohio is nearly bankrupt following the closing late last year of the Randall Park Mall, once the largest mall in the Cleveland area. ‘It could simple cease to exist as a city,’ says Cuyahoga County Commissioner Peter Jones.”

Death, it seems, is contagious.

I went by the mall again on Wednesday night, the week after Memorial day. It was dim inside; no natural light poked through the skylights. There were fifty people, maybe less. The escalator was broken, so I took the stairs to the second story. I talked with Tim, the owner and operator of Heavenly Hands barber shop. The shop was empty. He was sweeping up in the back and he didn’t ask if I wanted a haircut. Tim is an older, bright-eyed man with a thick black beard. I asked how business is going, and he said business is good; he’s expanding. The store across the way just closed, so he’s opening a salon in the space.

“A salon,” he told me, “brings in five times as much as a barber shop.”

I ask him if they’ve seen business drop off after Dillard’s left.

“Not really,” he says. “Most of our foot traffic comes from Sears. And besides. We have a very specific clientele.”

“Who’s your clientele?” I asked.

He looked at me like I was a moron. “Black people,” he said. “That’s how I knew you weren’t here for a hair cut.” Just then a kid walked into the store, threw away his slurpee, and walked back out again. “See that?” he said. “If that kid had been white, no way he’d walk in here just to throw his slurpee away. No way. People know where they belong.”

Tim and I talked for an hour about barber shops and his strategies for bringing in customers; how he puts up posters in the windows of people with haircuts his staff could never recreate. “In a mall,” Tim said, “You have three seconds to capture someone’s attention. They walk by, look inside, make a decision.”

I ask if he’s worried about the mall dying.

“I’m not,” he said. He heard they have a plan: a movie theater where the Dillard’s used to be. “Because right now,” he said, “that’s the dead zone. That’s the Dillard’s dead zone. Nothing can survive over there right now.” When I got up to leave, the mall was closing for the night. The storeowners were pulling down the metal barriers; the lights were shutting off in sections; darkness moved from one side of the mall to the other. A security guard walked by and told me it’s time to go.

I came back on Saturday and the parking lot was so hot that the black asphalt stuck to my shoes. I walked to the Dillard’s dead zone and sat on the edge of a concrete planter. In front of me, a kids’ playground sat unused, the color draining out of the plastic. The doors to Dillard have been locked and blacked out. You can’t see inside. Behind them are a hundred and seventy-six thousand square feet of empty space. Next to Dillard’s were the remains of a mattress store. On the opposite side, a Regis hair salon was open but empty. I talked to the guy at the counter. I asked him if he knew he was in the dead zone.

“Of course I know I’m in the dead zone,” he said, “I’m in the dead zone,”

He told me that almost everyone in the dead zone is trying to get out of their lease. I asked him if Regis is trying to get out of their lease too. He said he probably shouldn’t talk about that, but then told me he doesn’t really know anything anyway. “All anyone ever hears are rumors. Then one day stores disappear.”

I asked him which store he thought would disappear next, and he told me what everyone else had told me: “That big-ass shoe store down there by Macy’s.” Nobody could remember its name. In a mall, a store isn’t known by its name. It’s known by its location, which I now realize is the only thing that matters. There were a couple shoe stores by Macy’s, but only one that I would call “big ass”: a shoe store called Encore, a wall-to-wall emporium of shoes and shoe displays and shoe benches with those slanted mirrors underneath. A No Doubt music video was playing on a TV in the corner. Boxes were stacked chest high and two deep. There must have been thousands of pairs of shoes here. I counted seven customers. Employees walked around with blank looks on their faces and customers moved slowly. The signs for fifty-percent-off sale were bright red.

An employee in a bright red polo shirt asked me if I needed help finding anything. His sleeves were stretched around his biceps. His hair was bleach blonde and spiked, and he wore a puka-shell necklace; he looked like one of the few types of people who still belong in a mall like this. I told him I was fine, and he snapped his fingers and walked away. A Jack Johnson song was playing now. A forty-year-old dad in a pink polo was trying on a pair of New Balance tennis shoes. A pre-teen was texting with one hand on her hip. A manager was slicking back his hair. These are the holdouts, the ones left behind. They don’t seem to notice that they’re the only ones here, or that this place is falling apart around them. This isn’t just the end of a mall, it’s the end of an era.

I didn’t come back to the mall for a month. When I did, on a Thursday afternoon, the mall was the emptiest I had ever seen it. In the month since I’d been there, the mall had continued to fade. Faster than I’d expected, actually. Most of the people I’d talked to were already gone. The Regis hair salon had disappeared. “Closed about a month ago,” the woman at the shop next door told me, just a few days after I’d stopped by. The sunglasses stand had been wiped clean. The woman at “Sassy Diva” had quit or been fired. Encore was still around. Tim at the Heavenly Hands barbershop was doing okay. He had just opened his salon, and when I went in to say hi, he was talking strategy with one of his stylists. He smiled and gestured around at his new place. It was new, bright, shiny, and completely out of place in Collin Creek Mall.

All photos copyright John Prichard, who was once chased out of Collin Creek Mall. Used with permission.

When You Dress Up Like Wednesday Addams but Get Mistaken for a Porn Star

by Matthew J.X. Malady

People drop things on the Internet and run all the time. So we have to ask. In this edition, writer Larissa Pham tells us more about what it’s like to get on the subway dressed like a member of the Addams Family and then have other passengers think you are a porn star.

oh also last night i got mistaken for a porn star on the A train. like, they thought i was a porn star IRL, dressed as wednesday addams

— larissa pham (@lrsphm) November 1, 2014

Larissa! So what happened here?

Okay, so you should probably know that I have a really recognizable face, but like, never as myself. I’ve been mistaken for Awkwafina and like six separate guys’ Asian girlfriends. No need to make a racist joke; I’ve just made it for you. Also, when I was at school people kept telling me they’d seen me at events I had no recollection of, and one guy got into this really long, involved narrative about how he watched me spread cream cheese on a bagel or something. And I had to tell him it wasn’t me. It might have been me at all those parties though, because I was crossfaded for most of college and don’t really remember it.

So, yeah, I was on the A train headed to Bushwick to meet my friend at a party. I was dressed as Wednesday Addams because my soon-to-be-ex bae and I were going to go as Clark Kent and Lois Lane, but then I decided not to visit him that night and also, how heteronormative. So Wednesday Addams, because I already own all the accoutrements of a sulky Victorian child.

There were these two cute black lesbian pirates across from me on the train, and I was checking them out, I guess, because queerness and femininity are marvelous and I was really into the spectrum of butch/femme vibes I was getting from their costumes. One of the pirates was all ringleted and sultry and the other pirate had braids and a leather lace-up vest — they were a very striking pair, very satiny. Like that store-bought Halloween costume vibe, but they worked it. Also, they were hot. It feels important that you should know they were hot.

Anyway, I hate Halloween, the same way I hate New Year’s Eve and pretty much any other holiday you’re supposed to go out and have fun on, because I hate fun. I mean, I LOVE fun, I am so fun, but I hate feeling like I’m supposed to be fun all the time, because that is exhausting and drugs are bad. I told myself I’d go out though — I just moved to New York like two months ago and I still need to make new friends (please be my friend), and I’m a person with a lot of social anxiety, so I was like, come on Larissa, do the thing. And so I was sitting there with headphones in, chillin, checking out these pirates.

It’s an animal thing, right, where you can tell that people are looking at you? This is how I make sure that I don’t die. Anyway, so I animalistically became aware of one of the pirates looking at me, and I was like, should I join your crew, unfriendly black hotties? in my head, and then they had this very not-quiet, not-subtle debate:

Pirate 1: It’s her, it’s her right?

Pirate 2: What?

Pirate 1: There . . . over there . . .

[Lots of glancing around at me while I play dumb and bop my head to Purity Ring]

[Incomprehensible muttering]

Pirate 2: Huh . . .

Pirate 1: She looks just like her.

Pirate 2: Nah, no way that little girl could be a porn star.

From which I surmised:

1. I look like a porn star.

2. I could never be a porn star.

Fair enough. Every so often I do think about sex work, and I have the utmost respect for sex workers, but it’s not in my temperament.

After the pirates reached a consensus that I was not, in fact, an adult industry performer whose oeuvre with which they were presumably familiar, they leaned back and kissed up on each other, and I giggled a little, because New York is a city where everyone comes from somewhere else and everyone looks like someone else, or is.

Then I got stranded in Williamsburg later that night, and it took me two hours to get home because Halloween is terrible.

What was the inspiration for the Wednesday Addams getup? And in what universe could Wednesday Addams be mistaken for a porn star?

My friend Austin and I decided that the worst thing you can say about someone’s Halloween costume is to call it, sigh, derivative, because lol all Halloween costumes are derivative. You are supposed to go as someone, so if you want to go as an asshole, say that and you will be the life of the party. Halloween costumes are also supposed to be easily read — this is a problem I’ve run into before, not being legible enough — and so you have to really get the signifiers of the character down in order to have a successful costume. Wednesday Addams is a very legible character with lots of easy signifiers, and I do happen to own a black velvet dress and knee socks and little black shoes, so it seemed like a natural decision.

I did not work the center part. But I do look really cute in pigtails. And I’m dark and sad.

The thing that tickles me about this story, though, is that the pirates didn’t think I was dressed as a porn star, but that I was myself the porn star IRL, who happened to be on the subway dressed as a sulky Victorian teenager. This requires a certain kind of familiarity with adult entertainment that I find a little funny and charming. Like, “Hey, really enjoy your work, love the costume.” Big kisses. XOXO.

I wish I knew which porn star they had confused me with. I missed that part of the conversation. I would have looked her up! Compared our moves! Do you ever wonder about all the possible lives you could have lived? I’m a narcissist, probably, so it would have been fun to think about an alternate future.

Lesson learned (if any)?

The next day, brutally hungover, I went to Connecticut and my Clark Kent broke up with me, for a number of reasons that I won’t get into here. I spent a lot of time on the train home crying and thinking about other ways it could have turned out. But there weren’t really any other ways, and after all, I am only one person, even if I look like a thousand others, but I am also me, so I guess I am special, I hope. I look like a porn star. I am lovable.

Just one more thing.

The world is full of fictions. Nobody is actually the famous person you think they are, but everyone wants to be famous and everyone wants to be loved, probably. But stop staring. It’s creepy.

Join the Tell Us More Street Team today! Have you spotted a tweet or some other web thing that you think would make for a perfect Tell Us More column? Get in touch through the Tell Us More tip line.

Matthew J.X. Malady is a writer and editor who was in New York but is now in Berkeley.

A Tibetan Refugee's Final Shelter

by Shashwat Malik

A short walk down the hill from the Dalai Lama’s residential complex in the North Indian town of Dharamsala is the Jampaling Elders’ Home, a retirement community run by the Central Tibetan Administration, the Tibetan government-in-exile. Jampaling houses a hundred and forty-five residents, many of whom are part of the first wave of refugees who fled Tibet in 1959, in the wake of a failed uprising against Chinese rule.

The early years of exile in India were a struggle for those who had left behind their traditional nomadic ways of life and found work building roads, as cooks, or in the Indian army. Many never married, and, having grown old, now have nobody to care for them. Jampaling Home is the final refuge for these refugees. This August, I went to Jampaling to photograph its residents and seek their perspective on the Tibetan conflict.

During my visit, police in Sichuan province opened fire on a group of Tibetans protesting the arrest of a respected village elder who had been urging local officials to allow a prayer ceremony as part of the Denma Horse Festival. According to reports, four of the ten protesters who were wounded died in detention. Another committed suicide.

Shortly after my visit, in September, a twenty-two-year-old student, Lhamo Tashi, immolated himself in front of a police station in Gansu province; since 2009, more than hundred-and-thirty Tibetans have resorted to this form of protest against Chinese rule. An old Tibetan man in Dharamsala told me that hearing such news from Tibet made him feel like a parent who has to see his child drown from afar; unable to save him, he can only watch.

For residents at Jampaling, the despair of the conflict is part of their daily experience of old age. And for many, their miseries are explained by Buddhist doctrine as retribution for acts of past lives; enduring them is meant to provide hope for being born into a better afterlife.

Thupten Rabten

“This is the end of our lives; there is nowhere to go from here. It is straight to the cremation ground,” Thupten Rabten said to me as we sat on a bench outside Jampaling. Thupten had just finished his afternoon prayers and could overhear the administrator-in-charge talk about preparations to be made for two residents who had died the day before. Sixty-three-year-old Thupten suffers from hand tremors. He was seven when he fled Tibet in 1960. “I was one of the kids picked out by the Chinese authorities to be sent to Peking to study,” he told me. “My father feared that I’d learn Chinese and forget the Tibetan language, that I’d be indoctrinated and turned into a communist. He thought I’d become somebody who would break the Tibetan nation. So he brought me to Dharamsala.”

Yangkey

Thupten’s roommate, ninety-four-year-old Yangkey, is unable to speak and spends most of her time counting her beads. Her husband was also a resident at Jampaling, until his death in 2006. Having no children, she has no surviving family.

Amdo Thubten Tsering

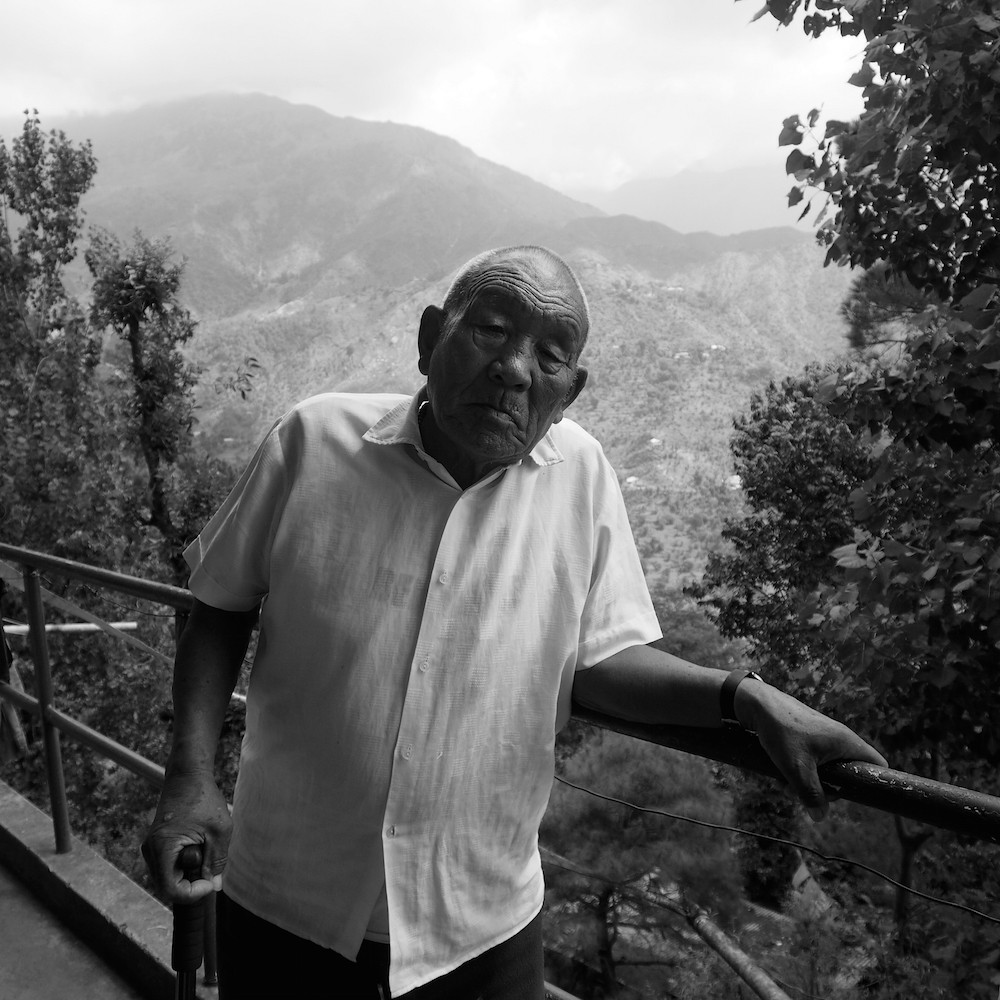

Two years short of being a centenarian, Amdo Thubten Tsering is the oldest resident at Jampaling. He said he fought as a guerrilla against the Chinese army in 1958. A year later, after the uprising failed, he was one of the eighty thousand Tibetans who fled across the Himalayas, following the Dalai Lama’s own escape. “I’m here, but my heart is still in Tibet,” he told me. “That is my country, that is what I fought for. I have grown old, and when I hear the news coming out of Tibet, I’m now not as hopeful about the situation as I used to be.”

Lobsang

“I’m about to die,” Lobsang said. “Going back to Tibet wouldn’t be possible, it seems.” He continues to look to the Dalai Lama for a resolution to the political deadlock with China. Since 1988, the Dalai Lama and the government-in-exile have slowly scaled back their demands for total independence, or “Rangzen.” They now agitate for what is known as the Middle Way, a demand for “genuine autonomy” within China, which is seen as an unacceptable compromise by many young Tibetans born in exile in India. It is also rejected by some elderly Tibetans, like the Khampa warriors of eastern Tibet, who fought the invading Chinese army in 1950 and then led an armed uprising in 1959.

Tenpa Tsering

But amongst those who took up arms at one stage or the other, there are some like Tenpa Tsering, who, out of reverence for the Dalai Lama, has followed his lead on the MWA. Eighty-two-year-old Tenpa, who lost his vision to cataracts, said he fought in Lhasa in 1958 and 1959, and then served in the Indian army for more than two decades. When I asked him how he views the possibility of the Tibetan struggle turning violent, he replied, “The Dalai Lama has shunned violence, and that settles the matter.” But he also isn’t terribly sure about the efficacy of peaceful protests. “That’s the way forward, but it may not yield results.”

Ngodup Palden

Ngodup Palden said he participated in the uprising in Lhasa in 1958. He also rejects the option of an armed uprising. “It just doesn’t make sense. We would be crushed too easily,” he said. “They are just too many and too strong.” He worried China’s economic clout has left foreign governments unable to talk about human rights in Tibet.

Early in October, the Dalai Lama cancelled a visit to South Africa over visa troubles for the third time in five years. It is widely assumed that his presence at the annual summit of Nobel peace laureates in Cape Town, to which he had been invited, would have been awkward for South Africa, which is pursuing stronger trade ties with China. (The summit itself was cancelled after several laureates withdrew their participation in protest over the denial of visa to the Dalai Lama.)

Jampa Nyichung

Jampa Nyichung broke his back and lost his legs in an accident, so he is mostly confined to his bed. He used his mirror to converse with me through the window, before inviting me in. He said that he misses the Tibetan landscape where he grew up in a family of nomadic herders. “When the Chinese first arrived, they lied that they would make things better,” he told me.

Beijing continues to sell Tibetan nomadic communities the promise of raising their living standards. According to a 2013 Human Rights Watch report, between 2006 and 2012, hundreds of thousands of nomadic herders in the eastern part of the Tibetan plateau were relocated or settled in new permanent villages. The report raised concerns over the ability of those resettled to maintain their livelihood over time; their nomadic way of life has been radically altered by China’s attempt to build a “New Socialist Countryside”, a development program planned in Beijing that is aimed at improving the economy and living standards in the Tibetan region.

“People inside Tibet are helpless, monks are getting jailed, and the army is brutal,” Jampa said. “We know this, these are facts, and yet the Chinese continue to lie. With their propaganda they tell the world that everything is fine.”

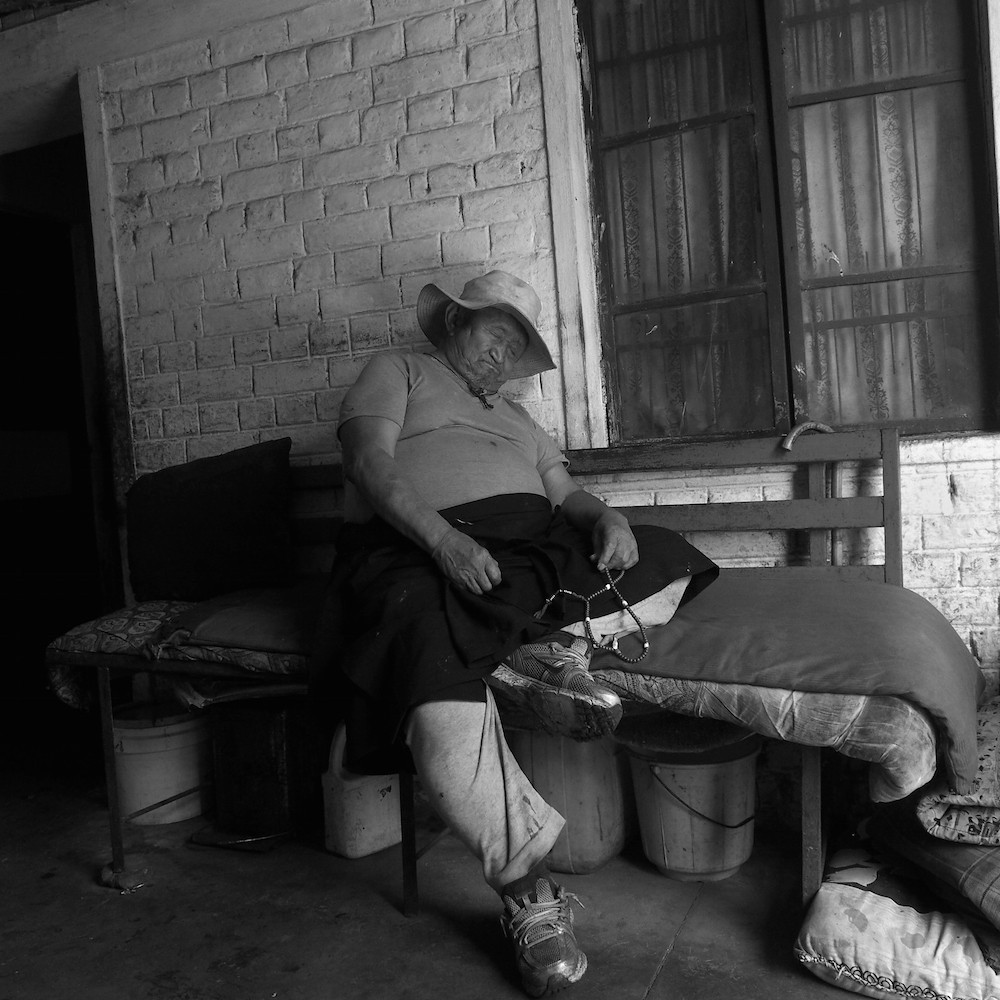

Samdup Paljor

Samdup Paljor kept dozing off fitfully, while chanting the prayer mantra, “Om Mani Padme Hum.”

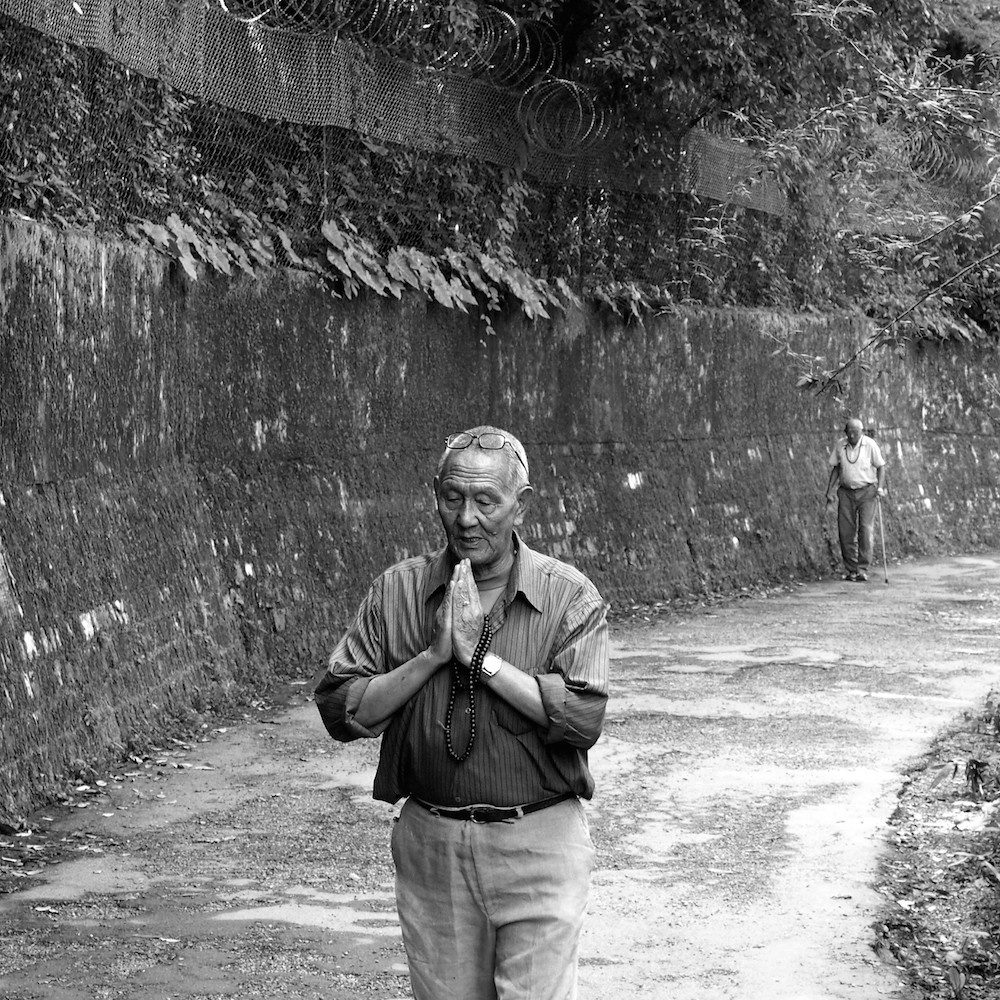

Tsering Thundup

Proximity to the Dalai Lama means a lot to the residents. After Tsering Thundup completed his kora — a circumambulation of the Dalai Lama’s temple complex — he told me, “I have to say it’s nice here, but it’s not my country. I still want to return to Tibet. A day doesn’t go by when I don’t think about it.”

Tsamchoe Dolma

Tsamchoe Dolma, who had a fever, shared her fantasy with me: the Tibetan issue has been resolved, and everyone at Jampaling is filing out, to return to Tibet.

Office Opened

The publisher Hachette is, for the moment, perhaps best known by dedicated readers of the New York Times business and technology sections less as the book house responsible for last year’s Pulitzer Prize-winning novel, Goldfinch, than as the stuffy old print empire whose pulp Amazon will not ship in a timely fashion. So it would be perhaps too perfect a tale that a legacy book publisher has embraced an open office plan, the epitome of technology startup office design, in like, the aughts, just as the tide has begun to turn against them in earnest because it turns out that they are terrible in every measurable way.

But it’s even better than that. It’s clear, in the Times’ telling, that Hachette didn’t move to an open office because it was under the increasingly outmoded delusion that a cubicle farm would be more conducive to a new kind of collaborative publishing work, boldly pushing past the outdated model of an editor locked in his private office with his leather chair and his lamp and piles books and stacks of weathered pages, endlessly tinkering with manuscripts in absolute privacy and silence. It’s just trying to not go broke:

But with their profit margins being squeezed by Amazon and electronic books, publishers are facing a different reality, one in which private offices may be a luxury that are not worth paying for. The trend started several years ago in London, where prime office space in desirable neighborhoods is typically even more expensive than in Manhattan. Penguin U.K. and Little, Brown U.K. are among the British publishers that have recently moved into fully open spaces.

This year, HarperCollins relocated to a largely open space in Manhattan. (Executive editors and above retained their offices, though most lost their windows.) But Hachette has become the first major American publishing house to abandon private offices altogether.

“I looked into the future and thought, ‘Are profits going to be easier to come by or harder?’ ” Mr. Pietsch said. “I think they’re going to be harder. We need to save as much money as we can and still have a nice office.”

…

The open plan may be the future of publishing, but for a lot of editors in this genteel, old-fashioned business, it’s going to take some getting used to.

“Having a door and a window is starting to feel like having a car and driver,” said Tim Duggan, who has his own imprint — and, for the time being, office — at Crown. “It’s almost too good to be true, and probably too good to last.”

It is all too good to be true: The window, the vast cityscape filled with millions of people going about their temporary lives that it looks out on, the endless sky above it all, the burning chunk of stuff shining down on everything to light our way in the infinite void of the universe. Everything is too good to be true and one day it will all be gone. Even you. Especially you.

Photo by John

Many Apologies to Taylor Swift

“Taylor Swift knows you think she’s ‘insane.’ In the music video for ‘Blank Space,’ which leaked online on Monday via Vevo and Yahoo, she plays on every single horrible girlfriend stereotype.”

Taylor Swift’s new music video has been released by one of the world’s largest websites in partnership with the internet’s leading music video hosting service. Or wait, was Taylor Swift’s new music video leaked by one of the world’s largest websites in partnership with the internet’s leading music video hosting service? If this sounds like a small distinction to make, between two nearly identical behaviors carried out in the same venue with nearly the same result, then you’re clearly not a Taylor Swift fan. This morning, the video seems to have been pulled, and Taylor Swift fans are sorry:

@taylorswift13 I’m sorry that your video got leaked, we didn’t know about that honestly or we wouldn’t have spread it like that.

— i know places (@ohmysugarcube) November 10, 2014

@taylorswift13 we’re sorry about the blank space video taylor, it just appeared out of no where and it’s not your fault it leaked

— Rebecca (@aussieslovetay) November 10, 2014

@taylorswift13 @taylorswift13 @BigMachine Im truly sorry taylor 🙁 I swear i didn’t know that it was leaked. Sorry sorry sorry sorry sorry:(

— TS1989 (@_Leonyarum) November 10, 2014

OH SO IT WAS LEAKED? My apologies, @taylorswift13 @taylornation13 But why did Yahoo release it too soon.

— celina//LauraBodewig (@_cagesandguns) November 10, 2014

@taylorswift13 is it actually leaked did i just watch a leaked video wow im done with myself

— idk (@littletownswxft) November 10, 2014

If only they had known, they would have averted their eyes. Perhaps they would have policed their peers, preventing them from watching this illicit intellectual property. Modern fandom is powerful and terrifying.

Meanwhile, on the very far end of the Taylor Swift fan spectrum, you can enjoy what has been called, soberly, the “dumbest Twitter thread ever:”

1/If @taylorswift13 raised venture capital instead of signing a record deal she would make 20x the $$ — and reach 10x as many people.

— jason (@Jason) November 9, 2014

It is breathtaking. And a valuable contribution to the quest for a pathology of venture capital. From each according to her investors, to each according to her valuation.

Gif by Casey Johnston.

Mars Retracts

“A reality television series is the lynchpin of Mars One’s plan. It is through this that it intends to raise the necessary capital to actually fund the mission via advertising revenue and broadcast rights. The proposal is to film the final candidates 24/7 for the duration of their 10-year training mission on Earth, from the selection process to liftoff, and then to continue to broadcast the mission itself, live, beamed in perpetuity back from Mars to viewers on Earth. There is currently no network buyer for the show.” — Awl pal Elmo Keep on the surprising and hopeless and surprisingly hopeless private mission to Mars.

New York City, November 6, 2014

★ A furtive whiff of marijuana lurked on the damp morning air under the scaffolding where the teens loitered before high school. “I’m wiping the rain off you,” the three-year-old announced, seated on shoulder top, swiping his hands ungently back and forth through the hair in front of him. The rain was light and annoying. A man did pullups on a bar of more scaffolding behind the Trump buildings, where the trapped lower branches of honeylocusts assumed various degrees of drooping. Somewhere in the gray, as the day went on, a pink tint appeared. The rain thinned to a drizzle, then a heavy mist. The after-school teens were few and far between. The mist gnawed at the tops of buildings and consumed New Jersey, fading out the view before the early night could get to it.