How to Successfully Hijack Your Family's Thanksgiving

A few years ago, I decided I would no longer be a passive consumer of food at Thanksgiving, but an integral part of the cooking process. My family’s Thanksgiving is mildly progressive: It begins with a platter of lox and chopped liver (which I thought was a traditional Thanksgiving starter until I was fifteen); our sweet potatoes are twice-baked, with dried cranberries and pecans; our gravy is an elaborate concoction of turkey stock and mushrooms and roux; and our pumpkin pie is sometimes a whipped pumpkin mousse.

To this, I decided I would add a vegetable, and settled on Brussels sprouts, done in a sort-of Momofuku style, deep-fried and served with a fish sauce vinaigrette. I didn’t have a deep fryer, so it took hours to make as roommates stood by with bags of flour and pot lids ready to stamp out any fire that might be caused by me basically just guessing at how to deep fry with a four-dollar thermometer and a soup pot full of oil. It turned out really tasty, I thought. When I brought them out, crispy and browned on a big platter with a nice gravy boat full of my perfect sweet/sour/umami/spicy vinaigrette, I thought I’d be the toast of Thanksgiving. For years to come, my family would say, “Remember Dan’s Brussels sprouts? Hope he brings those again this year. And also his anecdotes were really charming.”

I placed a few sprouts on my mom’s plate, dressed them with the vinaigrette, and waited. She tried one. “Oh,” she said. “It’s really interesting.” The sprouts remained at the end of the meal, maybe half gone; I probably ate most of them. But I learned my lesson: Thanksgiving is not a time to be edgy, trendy, or challenging. But! I think there are a few ways to bump up the tastiness of Thanksgiving while still staying true to the flavors and themes of the meal. And, guess what? They all involve fruits and vegetables.

Thanksgiving is the only harvest holiday a lot of Americans celebrate, and the traditional dishes are so ingrained in us that we tend not to even know why we eat this stuff, just that it is what one eats on this day. Which is great: It’s kind of where I’m hoping our current food obsession takes us, to a future where we just naturally eat what’s in season, not because that’s the trendy thing to do but just because, well, that’s what we do. In that way, Thanksgiving isn’t just one of the most traditional American holidays, it’s also very forward-looking.

I mostly love traditional Thanksgiving dishes, because who wouldn’t? Turkey is hard as hell to do right, but when it is, it’s ridiculously rich and flavorful. Labor-intensive dishes like stuffing and gravy are ceremonially prepared. People who normally never eat sweet potatoes do. Green beans and cranberries cut through the richness and fat of the rest of the meal with crispness and sweet-sour bitterness, respectively. These flavor combinations are great. They are thoughtful, sophisticated, balanced classics.

But I look through the many, many Thanksgiving tips and recipes that litter the internet this time of year, and I think they sort of miss the point in some ways. The Times, for example, has a beautiful splash page with dozens of Thanksgiving recipes, most of which look really tasty, but would provoke the same reaction my mom had at eating those deep-fried sprouts, because they miss the really essential thing about crowd-pleasing Thanksgiving fare, which is not to bring new flavors to the five or so traditional ingredients — it’s to use familiar autumnal flavors. If there are new ingredients though, that’s just fine.

I’ve taken the liberty (lol) of planning out a whole menu of additions, from hors d’oeuvres to dessert, with that in mind: traditional fall flavors, prepared simply, to emphasize the great things about Thanksgiving.

APPETIZERS

Homemade Membrillo With Manchego: So this appetizer can either be sort of tricky or the easiest one you’ll ever make. depending on whether you buy membrillo or make your own. Membrillo is a paste made out of quince, a hard fall fruit somewhere in between an apple and a pear in appearance. (This recipe is not mine; it’s from here, with a few changes. The main difference: I use vanilla extract instead of a vanilla pod, because who am I, Donald Trump?)

For the hard way: Basically, take about four or five ripe quince (you’ll know when they’re ripe when they’re completely yellow and smell sweet and fruity), peel, core like an apple, and chop into smallish pieces. Throw them in a pot with some lemon zest and boil until tender. Drain, then blend somehow; an immersion blender is fine, though I like a food processor for this because it makes a smoother paste. Put the quince puree into a sauce pot, along with an equal amount of sugar, plus a few drops of vanilla extract and a squeeze of lemon juice. Stir over low heat until the paste turns this really lovely amber color. This will takes forever — more than an hour. You don’t have to stir it the whole time like you would with polenta, but go back every few minutes or so to make sure it’s not sticking or burning. Then preheat your oven to really low, like 120 degrees if you can, and butter a square baking tray liberally. Pour the membrillo into the tray and bake for about an hour, until set. To serve: Cut the membrillo into squares, then the squares into thin square slices. Place a slice of some kind of sharp cheese — manchego is traditional, cheddar works just fine — on top. You can put this on a cracker, if you want.

If you don’t want to bother with making your own membrillo, here’s the recipe for this appetizer: take some store-bought membrillo and put some cheese on it now you’re done.

Delicata Squash Crostini: Delicata squash, oblong, usually pale yellow with grooves of green running down its sides, is sort of an in-between squash; it’s in season now, but it has qualities of both summer squash like zucchini and winter squash like butternut. Its flesh is sweet and roasts to a near-mush, the way winter squash does, but the skin is edible, and the flavor is not quite as heavy as, say, a butternut or an acorn. To prepare: slice lengthwise, and scoop out the stringy guts and seeds, reserving the seeds and throwing out the guts. Wash and carefully dry the seeds — a salad spinner might be helpful for this — then lay down in a single layer and roast in a toaster oven set to 350 degrees until they lightly browned and crisp. While the seeds are roasting, slice the squash halves into half-moons about half an inch thick, toss in oil, salt, and pepper, spread on a baking sheet and roast at 400 degrees until tender in the middle and brown and crispy on the outside. (Do not crowd the pan; the squash will let off moisture as it cooks, and if there’s too much squash per square foot, the moisture will cause the squash to steam, ew.) Don’t be shy about the oil.

While the squash and its seeds are roasting, make your pesto. Take sage leaves, parsley leaves, and walnuts in about a 4:1:1 ratio, and blend in a food processor with a lot of olive oil. Add a squeeze of lemon.

To serve: take a toasted slice of baguette or whatever bread-like item you want, spread ricotta cheese over the bread, then add maybe a quarter as much sage pesto in the middle of that. Lay down a slice or two of roasted squash and finish with a few squash seeds and a squeeze of lemon, or pomegranate molasses if you have any.

AUTUMNAL SALAD

Fennel, Raw Beet, And Walnut Salad With Persimmon Vinaigrette: Real good crunchy sweet salad here. Get a handful of walnuts and put them on that little toaster oven baking sheet and toast them at 350 degrees in your toaster oven until browned but not blackened, maybe 10 minutes. Take a bulb of fennel, trim off the stalks, and shave the outside of the bulb with a peeler or just carefully with your knife (the outermost layer is a little stringy). Cut in half through the root, lay it on the cutting board flat side down, and slice width-wise thinly. Get some pretty beets — chioggia, the candy-striped ones, if you can get them — and trip off the root. Lay it down on the flat side you just cut, and with your knife, working from the top, shave off the peel in vertical strips, losing as little flesh as possible. Then cut the beet in half from top to bottom and slice thinly into half-moons. Throw this all in a big bowl, along with a some bitter greens like frisee or chicory.

Take a hachiya persimmon, the kind of pointed one, and make sure it’s beyond soft, all over — it should be squishy and feel like there’s no way it’s not rotten. Cut off the top, and using a spoon, scoop out all the guts. Throw that in a food processor and blitz until smooth. Then add in about a tablespoon of white wine or champagne or even apple cider vinegar, adding it slowly then mixing then tasting to make sure it’s not too sour, and then, while the food processor is spinning, slowly pour in olive oil through the hole in the lid, about as much olive oil as vinegar. Taste and adjust; if too oily, add more vinegar or persimmon: if too sweet, add more vinegar, if too sour, add more persimmon. When it’s just right, pour over the vegetables and toss, seasoning with salt and black pepper. Add toasted walnuts, some reserved fronds from the fennel stalks, and, if you want, some goat cheese at the end.

REAL GOOD VEGETABLES

Roasted Endive With Walnut Vinaigrette: Endive, in the dandelion and chicory family, is a slightly bitter winter vegetable consisting of a whole lot of nested leaves, sort of like a jumbo, boat-shaped Brussels sprout. Here’s a real simple recipe. Preheat your oven to 425 degrees. Then take a whole bunch of endives, trim off the root, and slice in half lengthwise. Take a baking sheet and pour some oil in it, then place the endives an inch or two apart, cut side down, before drizzling some more oil on top and sprinkling with salt and pepper. Roast until the cut side is browned and the endive is soft the whole way through, which is going to take longer than you’d think — probably at least an hour. While that’s roasting, make your vinaigrette.

Break walnuts, if whole, into smallish pieces, toss in a little olive oil, and spread evenly on your tiny toaster oven baking tray. Roast at 400 degrees until toasty, which should take about thirty to forty-five minutes. Chop up one shallot very small and put it in, preferably, a glass Tupperware thing. Pour in some white wine vinegar and a squeeze of mustard over the shallot. (Dijon is classic, but I use spicy brown deli mustard because I have the palate of an old Jewish man.) Let that sit for a little while. Then add in an equal amount of walnut oil as vinegar/mustard. (This is more vinegary and less oily than most vinaigrette recipes call for. I am aware of that, but am also firm in my belief that a sauce that is seventy-five percent oil is gross.) A note about walnut oil: it is very tasty, but like a lot of nut oils, goes bad pretty quickly, so be careful. When the endive is done, take it out of the oven, turn it upside down so the amazing-looking cut sides are facing up, and sprinkle the roasted walnuts over them. Then pour the walnut vinaigrette over the whole thing.

Sunchoke Puree With Parsley Pesto: Sunchoke, or Jerusalem artichoke, is the tuberous root of a plant in the sunflower family, and it’s native to the entire eastern coast of North America, from Canada on down to Florida. It’s in season now, and makes a real nice alternative or addition to the typical mashed potato; it’s a little bit lighter and sort of nutty in flavor, which is nice. You can cook it pretty much the same way you’d make mashed potatoes: cut into smallish pieces, boil until tender, then puree or mash with some fat and salt and pepper. I like to add cheese of some sort to my mashed tubers, no matter what they are, so after they’re tender, drain the pot of water and add a heaping spoonful of either cream cheese or a mild chevre to the pot, along with some milk and a little butter. Sprinkle in a touch of nutmeg to emphasize the sweetness of the sunchokes, add a lot of salt and pepper, and combine somehow. For sunchokes, I actually prefer a smoother blend; I like a good chunky mashed potato, but sunchokes are so much lighter that a smooth puree doesn’t feel as glue-y as mashed potatoes can. Throw this in a food processor until smooth. Spoon it onto people’s plates and top with some dabs of parsley pesto, which is: one bunch of parsley leaves, washed, plus a clove of raw garlic, a small handful of toasted walnuts, and a lot of olive oil, tossed into a food processor until smooth.

BIG MAIN DISH

Roasted Brassicas With Pomegranate And Hazelnuts: So, there is a trend to roast brassicas, especially cauliflower, whole. I have mixed feelings about this. It certainly is a dramatic, impressive presentation, and anything that encourages people to roast more cauliflower sounds good to me! But I think this is not a great way to do it, since by cutting the cauliflower into small pieces, you increase the surface area and the amount of cauliflower that actually touches the pan, which will then get especially browned and crispy and seasoned. The more of that the better! I have tried the whole-cauliflower thing just enough times to say that I don’t think it works that well.

Instead, opt for a big platter of a melange of brassicas. Get one head each of a few kinds of brassicas: purple, orange, or white cauliflower; broccoli; and romanesco. Cut them all into pieces no bigger than a golf ball, and then cut them in half, so each piece has a substantial flat surface. Take each brassica and put them in a mixing bowl and toss with a lot of olive oil, some thinly sliced onion (about half an onion per head of whatever you’re using), some fresh or dried thyme, and a handful of hazelnuts (get the pre-blanched ones that are already peeled and white). Keeping each type of brassica separate, spread them on an oiled sheet pan. Turn them so the cut, flat side of the brassica faces down on the pan, making sure that there’s at least a centimeter of space between each one. You should have one sheet pan with each different kind of brassica on it, because they all have slightly different cooking times, and because keeping them separate will keep their colors bright and not muddied. Yes, this is a huge pain, but, you know, it’s Thanksgiving!

Roast them at 400 degrees until the bottom of the brassica — the flat side that’s touching the pan — is golden brown and almost looks like you’ve deep-fried it. When they’re all done, mix them all up in a platter with salt and pepper, and top with a handful of pomegranate seeds, a squeeze of lemon, and maybe another drizzle of olive oil.

Pomegranates are also in season right now, though I don’t think the Pilgrims ate them. Still! My preferred method of tackling a pomegranate is to take my shirt off (the juice leaves a powerful stain), then make a slit just deep enough to get through the skin and hold my knife at that depth while rotating the pomegranate to make an equatorial cut through the fruit. It’s sort of the same way you’d open an avocado except you don’t cut very deeply. Then dig your fingers into this gouge and pull apart slowly but firmly, and the pomegranate should break into two pieces. Do the same thing on the skin of each pomegranate half to cut and then break them into quarters. Then get a big bowl of water and hold each quarter under water while gently scraping the individual arils off. The arils will sink to the bottom, and the inedible white pith will float. Easy! I mean, not easy at all, but pomegranate tastes great, so.

DESSERT

Pear Crisp With Cardamom: I can’t bake, at all. I fear it. I fear having to measure, and not being able to adjust mid-way through if something goes wrong, and the sorcery that is dough-making. This is a sweet dessert that does not really require baking. Get five very ripe bosc pears — they’re rotten by the time they’re soft to the touch, so what you’re actually looking for is a little bit of wrinkling up top, around the stem, and for just that little part of the pear to be slightly soft; the rest of the pear should still be quite firm.

Preheat the oven to 400 degrees. Slice the pears into inch-long, fairly thin slices. In a cast iron pan, melt a few tablespoons of butter, and when it’s melted, add a few teaspoons of salt and a teaspoon of ground cardamom. Add in the pears and stir to combine. Separately, in a big bowl, combine about a cup of rolled oats, a few tablespoons of all-purpose flour, half a cup of dark brown sugar, a few grinds of salt, a couple drops of vanilla extract, and a teaspoon of cardamom (again). Take a stick of cold butter and drop it in the bowl, mushing all the other stuff into it until the butter is basically dispersed. Mark Bittman, whose recipe is close to mine, adds nuts to this mixture. I don’t like nuts in my crumble but I guess it wouldn’t be crazy to add some chopped pecans here.

Spread the oat mixture evenly over the top of the pears, then put the whole pan in the oven until the topping is crispy, about forty-five minutes to an hour. Serve with a relatively neutral ice cream, like vanilla or dulce de leche.

What I learned from my disastrous experiment with fish sauce and sambal oelek is that Thanksgiving is a bit of a high-wire act. It’s a culinary holiday, and the desire to impress is built into it. (I mean, why else would anyone roast a turkey whole when it’s the worst possible way to cook that bird?) But people have expectations. We expect fall flavors; we expect seasonal produce; we expect a pattern of dishes that matches our taste memory from last year and the year before. While, in most cases, I do not recommend giving people what they want, Thanksgiving is a time to cheerfully give in, to watch football even though it’s somehow both violent and boring, to let your eyes glaze over and think about other things during your uncle’s questionable rants on race relations, and to cook the food your fellow family and friends actually want to eat. Just once.

Photos by Ann Fisher, Charles Haynes, ulterior epicure, and Kristen Taylor

Blonde Redhead, "The One I Love"

Kind of a rude seasonal tease from Blonde Redhead. Yesterday Manhattan looked a lot like this, except it was much darker and much colder and nobody was smiling, not even by accident. The soundtrack, however, would have been just right.

Subject Not Unaware

“I am Hae’s little brother. Do not ask me anything.” Regarding the astoundingly popular Serial, a word from the family.

New York City, November 16, 2014

★ The clouds were a gray ceiling on the day’s potential. What people were on the streets were in drab and puffy clothes; the light on the buildings was flat, and the leaves, finally turning various colors, were dull versions of those colors. A white-haired man carried a snowboard under his arm, a few doors down from a tanning parlor. The air reddened the seven-year-old’s face. The sidewalk retail tables on Broadway were battened down with plastic sheeting and untended.

The Cone of Spotify

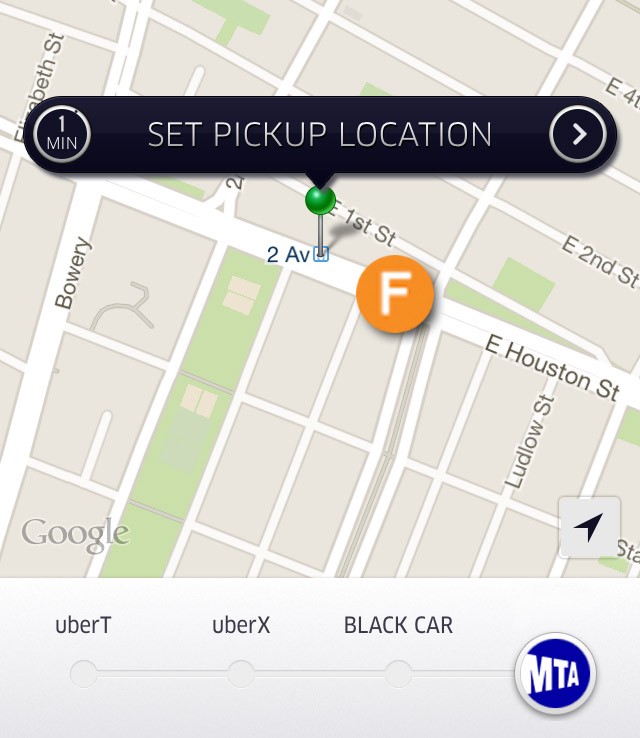

In New York City, the environments of taxi and livery cabs are circumscribed in fairly specific ways by the Taxi and Limousine Commission. Passengers have the right to, among other things, “a smoke and scent free ride,” “air-conditioning or heat on request,” “a car that is clean, in good condition, and has passed all required inspections,” “a driver who does not use a cell phone while driving,” and “a quiet trip, free of horn-honking and audio/radio noise.”

These “rights,” while they largely regulate the driver’s behavior, are generally engineered toward creating as neutral an environment as possible, for both driver and passenger: When followed, the cab and its occupants suffer no remarkable sights, sounds, or smells; everyone in the vehicle remains equally unoffended. There is a bland plane of mutual respect — a human performing a service, another one paying for it.

Uber first subtly shifted this power dynamic by making cars immediately responsive to the remote-controlled beck and call of passengers. The old livery system, of calling a car service to kindly request that it dispatch a car to your location, maintained a more balanced power dynamic between driver and passenger; if you sounded like an asshole when you called a car service, you would possibly remain alone and stranded, where you belonged, while Uber requires drivers to accept some ninety percent of requests. (This is, however, in other ways, a most welcome disruption: It effectively blinds cab drivers to their customers, removing their ability to discriminate against potential fares for the wrong reasons — so long as they have money to afford an Uber car in the first place.) Further, by abstracting away the process of payment to near invisibility, it removed the concrete gesture that reinforced the fact that the passenger was paying real money to another human for their labor.

Uber’s newest feature, Soundtracking, allows passengers with a Spotify Premium subscription to commandeer a car’s sound system in order to play their favorite songs; they can queue up their music in the Uber app before the car even arrives. The shift is small but potent: The passenger now not only controls the location and vector of the car, but its ambient environment, with entirely optional regard for the other human behind the wheel. That human, one of the most visible laborers in a globalized world of luxury that is largely powered by invisible labor, is rendered a little less perceptible, literally muted by the acoustical products of the pop culture economy. (While, for now, drivers can opt out of allowing Spotify in their car, as Valleywag points out, it’s unlikely to remain so for long.)

By subjecting cars and their drivers to more total control by passengers, Soundtracking furthers the ongoing logistical process of dehumanizing Uber drivers, who will, at the end of it, be nothing more than a bundle of route optimization algorithms, machine vision, and mutually beneficial startup brand synergies: Seamless some food to your apartment, right from the Uber app so it’s waiting for you when you get back; let your Airbnb host know that you’re on the way from the airport; catch some complimentary HBO Go while you’re in the backseat; or book a table at your favorite restaurant with Reserve.

Besides, what are people with Rdio supposed to do?

Mamiffer, "Flower of the Field"

Isis, the band, writes songs that run long and build slow. When they eventually pick up and/or accumulate, guitarist and vocalist Aaron Turner usually shows up with a nasty growl. Here, behind vocalist Faith Coloccia, he plays guitar but otherwise stays quiet. The song never gains momentum; it drones and slows and eventually just falls apart.

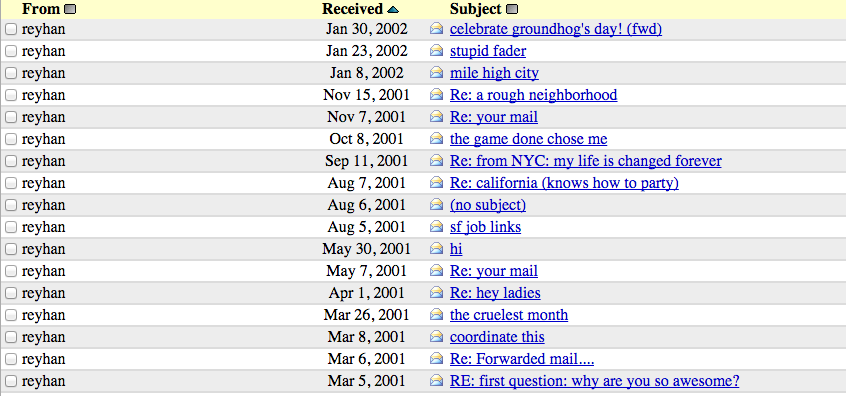

Every Email Is a Ghost Story

by Reyhan Harmanci

You think you know someone. Then you find your college email account.

Towards the end of a dinner party with four old friends, when the wine gave way to whiskey, we began reminiscing. The subject turned to how much we didn’t remember from those years and an alarming fact surfaced: Someone at the table had transferred her college email to Gmail. With a few taps, she surfaced a long-suppressed history. “What kind of maniacal mind would do that?” Jenny asked, frowning. Another diner attempted to trace the email archive’s journey: It had gone from a turn-of-the-century system called Telnet (think blue background, orange letters, all DOS-style text) to the Wesleyan University web browser to Yahoo! Mail to, finally, Google. What kind of maniacal mind, indeed.

It turns out that ancient emails make for a great party trick. Claire chronicled her time spent studying in an email entitled “barf”:

“i am working and writing and yet the paper refuses to get to 1000 words. i hate it! where are you working today? there is a hurricane outside and i keep farting.

yuck.

There was a dramatic reading of a note that I wrote, entitled “destinys child.” In it, I expressed a deep desire to acquire and consume alcohol:

at the rate i’m going, i will be in the hospital before the end of the week, so i’ll have to be wheeled downstairs to the ballroom in a full-body cast for the semiformal. I’ll have to pay someone to hold my drink next to my moveable cot since even being in traction couldn’t stop me from drinking.

Poetry.

The next day, though, I woke up unnerved and dimly remembered getting badgered by Wesleyan after I graduated in 2001, asking me to do something to save the messages after they were transferred onto a web-based system. I typed in “email.wesleyan.edu” and my old username, just to see what would happen.

It opened up with my first guess at a password. Over four thousand emails — including sent mail, drafts, “_pine_interrupted_mail,” something called “dead letter” and another folder called “postponed_msgs” — stared at me. Who were these people? Who was I?

hi guys. i wwant to apologiz

I must have spent half of college ducking into a computer lab, sending group emails. The bulk of the messages were to my friends on campus, who were locked up in computer labs or waiting elsewhere, patiently, for the static of a dial-up modem to clear. (It was probably possible to email my parents but I couldn’t find any messages to them in my account.) One thing that never occurred to us — or at least to me — was whether those messages were being stored. But of course they were.

The truth is that we are surrounded by digital ghosts, easily conjured. The notion that people, especially younger people, are vulnerable to bad digital decision-making has risen to the level of public policy — Europe recently enacted a “right to be forgotten” law that has Google excising unpleasant links from individual search histories. But the idea that some indeterminate past self can fly out of nowhere is disconcerting beyond, say, a prospective employer seeing an embarrassing picture. Self-respect, to paraphrase Joan Didion, isn’t about the public face of things — it concerns a “private reconciliation.” Locked in my college email box were drafts and funny notes but also a trove of strange saved messages. They were emails that I had written and for some reason — sentimentality, pride — felt compelled to save. Most were unsent. They were, I think, an attempt at love letters.

One of the oldest saved messages was a personality survey that had gone around campus, where you get someone who knows you to fill out questions about your life. I sent it to an ex-boyfriend and then saved his reply. “Ok, I took the time out to go through this questionnaire. I hope we aren’t enemies now,” he had written, blithe to my obvious desire for attention. Well, not completely blithe: “Again, in no way does this summarize the many ways in which I see you and think about you, but I also know that you really love to get email responses.” In my unsent folder, another kind of horror awaited. Think, say, two dozen emails of varying degrees of forced casual responses to… god only knows what. What the hell was I so upset about? The end of a paragraph about classes came one typical zinger: “By the way, did I ever mention that I harbor lots of anger towards you that I never got around to expressing?”

Buried in another folder, labeled “eclectic,” sat another surprise: notes from Chuck, this mountain of a guy and a Wesleyan legend who graduated a few years before me. He oddly befriended me when I was a freshman and he was a junior. When I first met him, he had taken a semester off but lived on campus, working at WesWings (even though he was vegan) while intermittently working on his dissertation on death metal music. The week before I graduated college, and was set to move in with him in a house in Boston, Chuck died unexpectedly in his sleep.

To this day, his death just doesn’t make sense. But the saved messages reminded me of all the tiny, dumb moments of our friendship that I had forgotten. The oldest email I have from him is dated 2:43 a.m., 1999, with the subject line “no offense”. Whatever he had said, I can’t remember, it seems to be some joke about my sexual prowess, but his misspelled apology is so sweet:

i didn;t mean to offend you tonight. i love you one million percent and the alst thing i want is for you to think that i think that you won;t ever get anyl.

I love the idea of Chuck earnestly apologizing for making a joke about me not getting any. If there was a redeeming aspect to all of this, it was the pleasure in being reminded of not only my past idiot selves but all my friends’ past idiot selves. We all used obtuse greetings (“hi pork,” “Yim Yimmer,” “kwan”) and wrote disastrous subject lines (“the game done chose me”). College was a haze of forward chains and personality quizzes and e-greeting cards and long, long letters during breaks as short as a weekend. There was no mistake worth making that couldn’t be sent to at least ten other people.

We weren’t reinventing the wheel: a few years before us, people would have sent actual letters and spent hours on the phone chronicling their fuck-ups. A few years later, all the action moved to a few weird apps. But we had email. No one older than us had more experience with technology than we did, and we had no concept that these messages were anything but ephemera. Email, at this point in our lives and its life, was still for fun, not just work.

So we made the most of it. The following is a message from a friend, forwarded to me twice:

And I still have no idea where my cell phone is. For some reason, I’m scared that the words “if you make out with me, I’ll give you my cell phone” came out of my mouth last night. I know I definitely thought that. Oh god. Did I make out with someone in exchange for my cell phone.

The cell phone was never found.

Photo by Alexander Baxevanis

How to Fix the New York Subway: Some Alternative Proposals

Subway fares are set to rise again, right on schedule (both literally and according to the grand theme of decline):

One proposal would raise the base fare for subways and buses by 25 cents to $2.75, while increasing the bonus on pay-per-ride MetroCards to 11 percent from 5 percent. A second proposal would keep the base fare at $2.50, but reduce the current pay-per-ride bonus.

These proposals only concern pay-as-you-ride customers — weekly and monthly rates will go up either way. (Weekly unlimited passes are currently $30 and monthlies are $112, and the MTA’s proposed system-wide four-percent hike applies directly, so they will end up at $31.00 and $116.50, rounded slightly down and slightly up, respectively.)

Setting aside that any price increases at all in a working public transit system are inherently regressive, increases to the weekly and monthly passes are generally more progressive, though not uniformly — there are plenty of people who need to ride the subway more than twice a day, for whom an unlimited card is an extremely high and necessary cost, and one not subsidized by work. Increases to per-ride costs, either direct or through a decrease in MetroCard refill bonuses, are generally regressive, though again, not uniformly — there are plenty of people for whom an unlimited card is a manageable but unnecessary expense, because they’re able to take cars much of the time.

This means that both proposals are effectively extra-regressive. Neither one suggests increasing the unlimited fees at a higher rate than per-ride fees: The first one increases the ride fare by eleven percent and then increases bonuses by six percent, resulting in an overall price increase of five percent, which means that the increase in cost would actually be slightly higher for per-ride customers than for unlimited customers. The second plan’s details — how much the bonus would need to be slashed — are still mystery. A bonus reduction to zero, however, would work out to a five-percent increase in per-ride cost.

So how do you structure a progressive pricing structure from where we stand now? Some ideas.

— THE ME TIER: A special MTA app, modeled after Uber, that presents subway data in a more rider-centric way. With this software, riders can “call” subways and buses, which will appear on a small map, giving Uber-seasoned riders an illusion of dominion over the entire city, including its public transit infrastructure and its employees (who will in fact be going about their business as usual). In the event that it doesn’t seem to work, or the wait is too long, or the trains aren’t going the right way, no matter: customers will switch back to the Uber app, which will satisfy them. But when the placebo effect works, imagine the feeling of POWER. Tagline: Everyone’s private conductor. Incorporate an alternative ride payment system into the app, linked to a credit card. Since this app’s users will mostly be Uber users, they will be fairly affluent. Charge whatever you want, surge price, who cares: It’s not real money, it’s app money. (Related: On-demand placebo apps represent a huge untapped opportunity. Uber for weather, Uber for birthdays, Uber for feeling like impulses have been satisfied. Call me, Marc Andreessen!)

— THE DEBT TIER: Replace the EasyPay Xpress service, which automatically pays your MetroCard from a credit card, with a credit-checked MTA account with extraordinarily high requirements and punitive interest/overdraft rates. In high-pressure platform situations — late for work, drunk and tired, shivering cold — account holders with insufficient balances would be incentivized to just blow through the turnstile instead of risking missing the next train trying to pull off a hasty refill. This would feel like a luxury product while barely being one; it would function as a small, lucrative predatory loan system for the city’s least vulnerable. Or just jack up the EasyPay Xpress cost more directly, or kill the bonus. Convenience costs something! Or just make paying with cash cheaper?

— THE LAZY TIER: A variation of an unrelated proposal by Alex Balk: Put the MetroCard refill stations after the turnstiles so that waiting, bored passengers, recently reminded of their low balances, will refill there. HOWEVER: Charge a fee. Budget-minded riders would avoid the booths as an obvious scam; other riders, bored without a phone signal, would absentmindedly swipe their cards. Make the interface vaguely Instagrammy. (Such kiosks could double as paid iPhone charging stations, or even Seamless drunk-ordering terminals.)

— THE FANTASY TIER: Purge the MTA and hand over board appointments to the de Blasio administration, which would undoubtedly be a enormous mess, but which would appeal to de Blasio’s idealistic side, his very softest side, and probably result in something still broken and weird but, in the end, closer to a public transportation system that exists for the purpose of public transportation.

Are some of these ideas silly? Sure. Stupid? Definitely. But who knows what horrors we’ll be considering in a few years, when the “higher than expected… real estate revenues” that kept this round of price hikes relatively low no longer apply. Gotta get ahead of the problem while we still can.

All My Friends Are in My Head

by Rachel Monroe

I used to talk to myself all the time. Now that I have a cat, I mostly talk to him. It’s not because I live alone; I did the same thing back when I had a half-dozen roommates, too. It’s great if you can find someone who’ll talk back, of course, but it isn’t entirely necessary; you can get by with a pet, an imaginary friend, or perhaps a pony-shaped thought-creature that you’ve manifested with your own mind.

As a young woman growing up in Brussels in the eighteen seventies, Alexandra David-Neel loved secrets: secret societies, esoteric religions, all things taboo and forbidden. She dabbled in Freemasonry, Theosophy, opera singing, and anarchist pamphleteering; she dressed up like a man to hang out with a French cult that smoked hash and saw visions. In her twenties, she began traveling to Asia. In Sikkim, she met the Dalai Lama; in India, she studied Sanskrit and took part in tantric rites. She spent two years living in a cave in Tibet with a hermit who wore an apron carved of human bone; he taught her telepathy and tumo, a Tibetan technique for generating body heat through breath, which they used to avoid freezing to death. Between adventures, she returned to France and published books about her exploits, which were devoured by a public eager for tales from the exotic east.

In With Mystics and Magicians in Tibet, first published in English in 1931, David-Neel described two uncanny encounters. The first was with a Tibetan painter followed around by a fantastic creature that looked just like the monsters in his paintings; the second was with another with a monk who had made an exact, living-and-breathing replica of himself to confuse his enemies. Both creatures were tulpas, which David-Neel defined as “magic formations generated by a powerful concentration of thought.” Stemming from a syncretic blend of Tibetan Buddhism and indigenous shamanic traditions, Tibetan tulpas were thoughtforms brought into actual existence through ritual meditation, a sort of mental counterpart to the Talmud’s mindless, mud-born golem.

Admitting her own “habitual incredulity,” David-Neel decided to try to make a tulpa herself. “I chose for my experiment a most insignificant character: a monk, short and fat, of an innocent and jolly type,” she wrote. After a few months of seclusion and diligent ritual prayer, her phantom monk began to take shape. Over time, his form grew increasingly fixed and life-like. Months later, when David-Neel left for an extended horseback tour through the countryside, her tulpa tagged along. By this point, she no longer had to focus her thoughts to make him manifest; he was just there, performing actions that appeared to be autonomous: walking quietly, looking around at the view. At times, it was as if his robe had brushed against her. Once, she felt his hand softly rest on her shoulder.

For the half-century or so after the publication of David-Neel’s account, tulpas remained an intermittent topic of interest for the cryptid/UFO/fringe science crowd. Shortly before his death, Philip K. Dick claimed to have manifested a tulpa of Walt Disney, who sat down at the table and ate the food placed in front of him, but hadn’t spoken — yet. In the 2001 updated edition of the Mothman Prophecies, John Keel posited that the titular cryptid might not have been an extraterrestrial after all, but rather an uncontrolled tulpa, a thoughtform gone rogue.

If there’s one lesson to take from all the self-published tulpa horror novels and message board creepypasta out there, it’s that tulpas have a tendency to get out of hand and exert their will on the world in troublesome ways. But maybe that’s what you get for creating a creature with a mind of its own, even if that mind was created inside your own head. Of course they’ll go rogue. Of course you’ll find them in places you never expected them to be.

To access the Tulpas Gone Wild board sub-reddit, you have to click a button certifying that you’re over 18. Then you’ll find a dozen or so threads with headlines like “Feeling a bit [f]risky tonight 🙂” and “Up for a little [m]ischief?” and “[F]ucked in public,” all of which are marked NSFW, and all of which link to images that are not only eminently SFW, but so dull that they look as though they might have been taken by mistake: a beige couch, its cushions slightly askew; the upper corner of a white ceiling. This is the world of the twenty-first century tulpa — an empty room, a digital camera, an online forum.

Tulpas started cropping up as a popular topic of conversation on 4chan around 2009. The growing community was eventually trolled out of 4chan; over the next few years, they moved onto scores of message boards, tumblrs, and blogs. Currently, the tulpa forum on Reddit, the central online gathering place for people engaged in creating “intelligent companions imagined into existence,” boasts nearly seven thousand subscribers (although far fewer active posters). Tulpa-creation as practiced on the internet would likely be unrecognizable to Tibetan mystics who conceived of tulpas as magically created manifestations. Redditors creating tulpas don’t think of themselves as shamans engaged in metaphysical edge-play; they tend to frame the practice as an exploration of human cognition, relying on an odd contemporary blend of mindfulness practice, folk neuroscience, and role-playing-game character creation.

There are a number of tulpa-creation FAQs out there, offering practical — even strict — advice: “You should spend at least twenty hours of just sitting down and visualizing your tulpa perfectly in your head. The very minimum you should be forcing for at one period is forty minutes. Also, don’t force for longer than three hours at a time or else you will get horrific headaches.” Forcing a tulpa, to use the preferred verb of contemporary online tulpamancers, is not for the wishy-washy. Getting your tulpa to the point of imposition — that is, where she appears as a fully 3D creature perceivable by all five senses, and capable of independent thought and action — can take months of daily practice. Judging from Reddit’s Tulpa Art Tuesdays, human tulpas tend to look right out of an anime casting call: all big, wet eyes, rainbow-colored hair, and dainty noses. Non-human tulpas include flirty squirrels, eyeless reptilians, and, yes, plenty of ponies. (The brony and tulpa communities overlap; around 2012, after the tulpamancers were trolled off the main 4chan boards, they found refuge in /mlp/, the My Little Pony board.)

Tulpa FAQs recommend spending three to ten hours concentrating on your tulpa’s smell alone, and five to ten hours sitting quietly, picturing its particular gait and gestures. After two months of daily practice, your tulpa might begin to show faint signs of independence — first communicating with you through flashes of shared emotion, then parroting your words back to you, and finally, hopefully, saying something on his own. “I did not get an emotional response until I hit around 50 hours in, so really, don’t hold your breath,” one prolific poster notes. “Remember that if a sentient being could be made in a day then everyone would have one.”

Even after achieving sentience, tulpas must be tended or else they’ll wither away, Tamagotchi-like, from lack of attention. The forums are full of suggestions for fun tulpa-host activities to sustain and deepen their connection. Some sound dull (addition flashcards); some seem pulled from a romantic comedy dating montage (cook dinner together, feed ducks at a pond); and some are outright bizarre (“Lie down, set a stuffed animal (with arms, sorry no snakes) and set it on your chest with its arms facing you, and ask your tulpa to ‘control’ the arms through possessing your hands. Then they can slap you like they’ve always wanted to!”). Some tulpas even post on Reddit, presumably through the bodies of their hosts, offering insider tips to new users: “When I was younger the host exposed us both to new experiences. We did not stay cooped up in his house, but went exploring on his days off from work. Then I could react to new things alongside him.”

As far as internet subcultures go, the tulpa crowd isn’t very popular. Outsiders are quick to assume that tulpamancers are at best hopelessly awkward and at worst somehow icky, as if despite all the “best friend” rhetoric, what they’re really after is a zombie sex-slave or yes-man (or yes-pony). The Encyclopedia Dramatic defines a tulpa as “an imaginary friend or imaginary girlfriend/boyfriend for batshit insane,lonely /x/philes, bronies, and weeaboos.” The hours tulpamancers spend forcing can seem not only pathetic but also unfair, as if they’re trying to reap the benefits of companionship without ever emerging from their rooms and having to do the hard, messy work of negotiating a real relationship with a real person.

Preliminary data from a study on the tulpa community dovetails nicely (in some ways, at least) with stereotypes of the undersocialized, over-internetted young man: Tulpamancers are mostly white, middle to upper-middle class urban youth, mostly between the ages of nineteen and twenty-three. There are three men for every woman in the community, although around ten percent of tulpamancers identify as gender-fluid. The prototypical tulpamancer is cerebral, shy, and socially anxious.

But as the study’s author, McGill anthropologist Dr. Samuel Viessiere, points out, dismissing tulpamancers as antisocial creepers is a mistake. While they report social anxiety and limited opportunities for in-person social interaction, they also display average to above-average levels of empathy and interest in other people. Being a person is sometimes inescapably lonely, even for the most socially skilled and likable among us; for the awkward and slightly askew, it’s exhausting. Human consciousness is intrinsically social and collective, Viessiere points out, but contemporary social processes are often isolating. Not finding the connection they crave in the world, the tulpamancers create it for themselves.

It’s telling, too, that the tulpa community’s most prized quality is autonomy. In true subculture fashion, there are lots of in-group words for all the wrong paths you might wander down. Are you trying to create a thought-creature for primarily sexual purposes? Then you’re making a mind doll, not a tulpa. Does your tulpa exist only to serve your own needs, without a will or an opinion of her own? Then she’s a servitor, and you might as well start all over again. Does your tulpa repeat your own thoughts and opinions back to you? Then he’s parroting, and while that may be a step on the path to imposition, it’s certainly not autonomy. For some posters, the practice of cultivating and nurturing a tulpa seems almost like rehearsing for a relationship: Ask your tulpa how she’s feeling, listen to her favorite music even if it’s not to your taste, go out and find some ducks to feed.

Ultimately, then, tulpamancy is the practice of creating an other within your own mind. This isn’t as crazy or improbable as it may sound at first. Our selves are fractured and plural, made up of parts that may seem external or even alien to us. Otherwise, sentences like I got so mad at myself wouldn’t make any sense. Some tulpamancers even sound like they’re working to manifest a Redditized version of their Jungian anima: “I am a white male, 27, single/foreveralone, and have a masters in computer science. I currently don’t have a ‘real’ job, so I have plenty of time for this. I’ve decided that my tupa will be a human female who I hope will be my closest friend, help me stay motivated, and help me explore my mind… I chose to make her female primarily because I feel that some part of my mind is feminine. This will give that part a chance to exist rather than be repressed by society’s rules about what it is to be male.”

Of course, belief in an independently functioning being that lives inside your own mind requires some logistical and metaphysical gymnastics: “Tulpas don’t go tend anywhere you can’t find them. You may only think they did. You’re in the same head after all. At most they’re off thinking by themselves for a while or ‘asleep’. People need their space.” Not all tulpamancers would agree with the above statement; the community is split between those who see their tulpas as metaphysical emanations and those who frame phenomenon in the language of neuroscience, with the latter group seemingly outnumbering the former; the subhead on tulpa.info is “For Science!,” and there is occasional excited talk about experimenting with EEG machines. For this group, tulpas are real in the way that lucid dreams or “advanced hallucinations” are real; your tulpa exists in your mind, and your mind creates reality, ergo your tulpa is real. (There are also some complicated theories involving neural networks and black boxes, if that’s what you prefer.)

The scientific tulpamancers are optimistic to the point of naiveté about the mind’s ability to act upon — or reshape — the world. In this way, they’re another link in the chain reaching from nineteenth-century New Thought to positive-thinking their way to a new car, vis-a-vis Oprah: If you visualize it, you can will it into being. The science-minded tulpamancers are not so different, then, than their more mystical-minded counterparts, only with neuroscience standing in as a kind of twenty-first century sorcery.

After a period of peaceful coexistence, Alexandra David-Neel’s tulpa, the jolly monk, began to change. “The fat, chubby-cheeked fellow grew leaner, his face assumed a vaguely mocking, sly, malignant look. He became more troublesome and bold,” she wrote. “In brief, he escaped my control.” Her former companion was now a burden; his presence began to feel like “a daynightmare.” She decided to dissolve him, but he didn’t want to go: “My mind-creature was tenacious of life,” she wrote. It took her half a year to get rid of him.

This could be read as a warning against errant tulpamancy, but I don’t think so. After all, aren’t we all always building mind creatures every day, whether we mean to or not? As a Tibetan lama tells David-Neel, “One must know how to protect oneself against the tigers to which one has given birth, as well as against those that have been begotten by others.” This is good advice for non-tulpamancers, too — even if you haven’t birthed any tigers recently, there’s a decent chance you’ve got something predatory living inside your head. Mindfulness meditation, tulpamancy, therapy; they’re all ways to try and be careful about what you’re nurturing up there.

Tulpa.info is full of stories of tulpamancers whose tulpas have been invaluable to their well-being. A girl who’s prone to panic attacks calms down when her tulpa runs his fingers through her hair; a guy who tends to stay up all night is convinced by his tulpa to go to bed at a reasonable hour. Sometimes, the tulpas intervene in more serious cases: “I was diagnosed and put on mood stabilizers when I was eight years old. After fourteen years, it seemed normal. But with Aura’s help, I have been able to come off of all my medicines, and have been free of them for the past five months. I would have never been able to if it hadn’t been for her helping me.” “I was actually on Lexapro for depression/anxiety for a while, and I went off of it cold-turkey about the time I created Flutters… [While on meds] I quit my job, stopped trying at school, would just sit at home all day and be extremely anxious if I had to leave. Luckily, I have been off of them, and Flutters has helped me improve immensely. I now have a decent job, am doing better in school, [and am] making music again.”

My tulpa’s name would be Cam, I decided on Day One, and he would be male, and human. His first few characteristics came easily: he’s a couple inches shorter than me, and he has a big nose. But when I tried to believe in him existing in the world, I was less successful; sitting on my couch, I tried to picture him sitting next to me, taking up an approximately human sized slice of space, but he remained featureless and eighty-five percent transparent, like a ghost or a failing hologram. “Cam,” I said, experimentally. “Hello, Cam. It’s nice to meet you.” Cam didn’t say anything back, maybe because I was doing a bad job of believing in him, but also because he hardly existed yet; according to typical tulpa timelines, he was barely a zygote. I fell silent, deciding that it was okay that Cam and I didn’t have much to say to each other at this point. Instead, I spent forty minutes projecting a vague sense of friendliness and camaraderie toward a human-sized emptiness on my couch.

On Day Four, following some of the tulpa FAQ advice, Cam and I went for a walk. Faced with all the visual distractions of the outside world, I had an even harder time imagining him there, but I made space for him on the path nonetheless. When there was a puddle to walk around, I went first, then paused and waited for him to catch up. This felt ridiculous, but it also felt fine. West Texas had a wetter-than-normal summer this year, and the path by the railroad tracks was bordered by thick grass as high as my hip, interrupted by occasional patches of happy-faced sunflowers. The grass was hectic with the sound of insects, and grasshoppers flashed the red undersides of their wings as they leapt out of the way of my — our — footsteps.

And so for an hour we walked like that, in companionable science, me and the inside of my own brain.

Photos by Keith Harrison, Rob Carlson, and Scott Rubin.

The Life of a Modern-Day Dungeonmaster

by Matthew J.X. Malady

People drop things on the Internet and run all the time. So we have to ask. In this edition, Kickstarter community manager Nicole He tells us more about what it’s like to lead a game of Dungeons & Dragons.

No one died in D&D today! (Except a bunch of orcs and a little torchbearer boy.) http://t.co/EUjqhlguwF

Nicole! So what happened here?

So we’re playing Dungeons & Dragons. For those who don’t know, D&D; is a classic fantasy tabletop roleplaying game about collaborative storytelling. Each player creates a character; say, a noble-but-asthmatic human fighter, or a sexy-but-irritating dwarf. Within the game, their goal as a team is to fight enemies and collect treasure. On a meta level, everyone is trying to invent a story and tell it together.

In this group, I am the dungeonmaster. (Dungeonmistress? Lol jk that’s a different thing.) While everyone else plays one character, I play the rest of the world. I control the monsters, the friendly townsfolk, the leaves rustling in the trees, and even the weather. The players describe through speech what their characters do or say (“I swing my sword at the orc!”), they roll some dice to determine the outcome, and I tell them how the world reacts (“You slice through his left thigh but he’s still standing. And now he’s mad.”). My purpose is to create meaningful decisions, encourage teamwork, and lead the narrative we are building together.

If all of this sounds kind of like a video game, it’s because lots of modern video games have basically been birthed from the loins of D&D.; But instead of sitting alone in your room staring at a screen and mashing RT on your Xbox controller to cast Fireball at the Hagraven, you’re sitting at a table with other people, a pencil, some paper, a bunch of dice, and your imagination. You have to make quick decisions and communicate with words to your team about what you want to do and why. As with anything involving human beings, it can get intense and emotional.

The version we’re playing here is real old school. We’re playing a module called The Keep on the Borderlands, which was first published in 1979. It’s essentially a dungeoncrawl, where the players explore an area called the Caves of Chaos, inhabited by a diverse group of monsters.

These old games are rather notorious for being deadly, and unlike video games, once you die in D&D; your character is dead forever. This sounds like not that big of a deal (IT’S JUST A GAME, RIGHT???), but the real life emotional involvement can actually be pretty serious. I once played The Keep on the Borderlands with another group, not as the DM but as a low-strength chaos elf. Ten IRL months in, one of our party — a Thief named Kermit — was attacked by giant fire beetles and died gruesomely. This was, no joke, one of the more traumatizing things that happened to me in 2013.

Anyway, back to the game you see in my tweet. It’s the dungeonmaster’s view, basically, behind the screen, which shows me the map of the world and where all the enemies and treasure are. The photo is a little spoiler-y, to be honest, so if you’re one of my players I wouldn’t try to look too closely at that map. This picture captured the second time we played, and unlike the first time, none of the players died! The only casualties were the orcs they were fighting and an NPC (non-player character) named Dun, a young boy who effectively acted as a meat shield. RIP Dun.

Lesson learned (if any)?

D&D; is having a moment these days. A lot of this is because it’s no longer being depicted as something exclusively for basement-dwelling, antisocial teen boys. I certainly didn’t play D&D; growing up; it didn’t seem like a thing that was particularly welcoming for someone who wasn’t white or a dude to get into, even though I loved both fantasy and video games. It wasn’t until a couple years ago when my coworker Luke started running sessions at work that I fell into this particular nerd hole and never climbed out.

After a while I felt comfortable playing roleplaying games, but DMing felt like it was a whole new level that I wasn’t quite ready for, even though this specific group of friends had asked me to run a game for them. But this summer, I went to Gen Con — the largest tabletop gaming convention in North America — for work, and everyone was so nice and friendly that I came back with a renewed sense of nerd confidence. Like, actually, this thing could be for me.

Playing this game with my friends and having a great time reinforced for me that this can actually be an extraordinarily inclusive space. It’s nice to have that reminder as a woman living in the midst of #gormergat.

Just one more thing.

The newest edition of D&D; was released at Gen Con this year, and the new rules make an effort to be explicitly inclusive. This is now officially in the most modern D&D; handbook:

You don’t need to be confined to binary notions of sex and gender. You can play as a male or female character without gaining any special benefits or hindrances. Think about how your character does or does not conform to the broader culture’s expectations of sex, gender and sexual behavior. For example, a male drow cleric defies the traditional gender divisions of drow society, which could be a reason for your character to leave that society and come to the surface.

You could also play as a female character who presents herself as a man, a man who feels trapped in a female body, or a bearded female dwarf who hates being mistaken for a male. Likewise, your character’s sexual orientation is for you to decide.

I think that’s pretty cool. If you’ve never tried D&D; before, now is the time to give it a shot.

Join the Tell Us More Street Team today! Have you spotted a tweet or some other web thing that you think would make for a perfect Tell Us More column? Get in touch through the Tell Us More tip line.