Now We Are Rome

by Gary Devore

“The torturer controls all proceedings. Arbitrary fallacies distort. Hope is corrupted. Fear debilitates. And with all of the constraints these things force upon the proceedings, there is no place left for the truth.” –Cicero

Hollywood has a long history of using the Romans to comment, often simplistically, about America. Traditionally, one aspect that has been presented in film as incompatible with American ideals is torture. It was always the purview of the brute, barbarian, and tyrant– the activity of a cruel, pre-Christian era. When characters from antiquity resorted to torture, the filmmakers consistently made the point that coercive violence was historically irreconcilable with a modern, enlightened democracy.

Throughout the twentieth century, as screenwriters strove to find innovative ways to repackage the clichés of Roman culture for the movie houses, depictions of torture remained interestingly consistent. However, despite the fact that it was an immoral practice, in their scripts torture worked. It produced useful information that drove the narrative, although they were clear to show only the villain would admit it to his information-gathering arsenal.

After torture became a topic of national dialogue with the discovery of the scandal at Abu Ghraib in 2004, and again with the discussion around the release in 2009 of Bush-era memos legitimizing the waterboarding (and worse) of detainees at Guantánamo, torture could no longer be used as simple narrative shorthand for a vicious, pre-democratic, pre-Christian, pre-American past. Studies even found that our modern torturers, torture apologists, and American officials who authorized the harsh interrogation techniques during the Bush Administration were influenced by Hollywood’s simplistic fictions where such acts were supposed to result in truthful, actionable intelligence. Our relationship with the characters we watched employ torture became increasingly more complicated, even if how they acted on screen were not exactly historically accurate.

Torture in the Roman World

The ancient Romans considered torture an issue of citizen and class rights. Legally, torture could never be used against a Roman citizen (although emperors and dictators sometimes disregarded the law). In one of his legal speeches, Cicero praised the nobility of an innocent patrician who, when publicly tortured by the corrupt governor of Sicily, would not offer anything other than a declaration that he was a Roman citizen. The implication of this assertion was that, as a citizen, he should have been protected from such treatment. Another Roman writer told the story of Lucius Varus, a former consul proscribed by the authorities who ran away from Rome only to be captured by the citizens from another city. Initially he claimed to be a common robber in order to hide from the warrant on his head, but when the citizens prepared to submit him to torture in order to force him to name his compatriots in crime, he came clean and begged to be killed in a manner more befitting his status.

The story of Varus illustrates the one area where torture was enshrined in Roman law. Evidence from slaves was only admissible in court if it had been elicited through torture. Presumably, apart from a clear indication of a slave’s inability to control his own body, this stipulation existed because to the Roman mind, testimony from a disenfranchised person was only reliable if it had been coerced through violence.

We do not have much information about the exact methods employed in Roman torture sessions. Flogging is often mentioned as a standard bodily punishment in the Roman world. In the Cicero passage mentioned above, fire and hot plates were used to burn the individual. Other sources mention the application of hot tar, fire, restraining collars, and devices like the stretching rack, but actual details are not found until the late antique and early medieval passion stories were created and filled with wildly imagined tools and methods for inflicting crushing damage upon the bodies of the martyrs, although most of these accounts are of dubious historical validity. Rome had a public executioner (like many other cities probably) called a carnifex who oversaw the torture and execution of criminals and slaves in the capital. Undertakers, because they had an intricate knowledge of human anatomy and dealt with death, could also be called upon by civic authorities and private individuals to torture non-citizens.

As with most aspects of history, the medium of film often simplifies, ignores, reinterprets, sensationalizes, and minimizes both the context and significance of torture in a Roman context. The practice has traditionally been used to easily demonize a villain and, until our current century, delineate the audience from those who would employ torture. The early 1930s, the mid 1960s, and the first few years of the 2000s were eras when various national crises were evident and ripe to be reflected in contemporary cinematic epics. The depictions of torture that came out of those periods were intricately connected to real-world events, and their reception irrevocably altered by the proceedings at Abu Ghraib and Guantánamo.

The Depravity of the Enemy: Torture in The Sign of the Cross

Cecil B. DeMille’s 1932 film The Sign of the Cross was based on a popular Victorian British novel and toga play that was well known in the US and the UK, having been staged extensively between 1895 and 1932 on both sides of the Atlantic. Set during the reign of Nero, it tells the story of a group of secretive Christians in Rome who are eventually rounded up by the Romans and executed in the arena. One of their numbers is a purer-than-pure damsel named Mercia who catches the eye of the Prefect of Rome, Marcus Superbus. Eventually, through her beauty and force of faith, she accomplishes his conversion (and subsequent death by hungry lion). Despite its heavy-handed religious propaganda, the film is (in)famous for the sensationalistic sex and violence DeMille was able to inject into the epic, which, despite the grumbling of the American Catholic press, helped the film earn huge profits for Paramount.

An early episode in the film involves the betrayal of a band of first-century Christians in Rome who are forced, because of the malice of a paranoid Nero, to meet in secret. A young Christian orphan named Stephan and his faithful dog live with the heroine Mercia. He is kidnapped by thugs looking for Mercia and taken into the bowels of an Imperial dungeon. Tigellinus, Nero’s Praetorian Prefect and henchman, decides to torture the boy in order to discover the secret meeting place of the Christians (and thereby both earn points with the Emperor and frustrate Marcus, whom he hates and suspects is having an affair with a Christian girl). Stephan cracks under torture, reveals the location, and eventually dies in the arena after a brief reunion with Mercia.

The Sign of the Cross (1932), the torture of Stephan (l to r): Stephan questioned in the dungeon; Stephan seized; Stephan lowered into the torture chamber; Tigellinus watching the torture and asking questions

The “torture of Stephan” scene is a powerful and horrific set piece and serves as an appetizer for the sort of sensational spectacles that will be on view in the arena by the end of the film. The dark, cavernous dungeon, full of shadows and grime, Tigellinus removes a hot poker from a fire and burns a piece of paper with it while a terrified Stephan looks on. “Answer,” the Praetorian intones threateningly. “There is a meeting tonight. Where is it to be?” Stephan holds his tongue, forcing Tigellinus to send him for torture. A great iron chain is pulled down from the ceiling and attached to a trap door in the floor. A winch pulls open a portal that is ringed with fiery light and smoke– a none-too-subtle metaphor for Hell. There are no sounds on the soundtrack except the clanking of the chains and winch and the struggles of a restrained Stephan as he watches, repeating “No! No!” The figure of the mutilated torturer emerges from the stairs below the trap door and Stephan is physically handed over to him as the boy cries, “What are you going to do to me?” No one answers, and Stephan is taken below out of sight, allowing the audience to imagine tortures far worse than what DeMille could dramatize in 1932.

Tigellinus pulls up a stool and sits at the top of the stairs to watch as Stephan’s horrific off-camera screams are heard. Several brief shots are contrasted against the boy’s yells: a Roman eagle, etched in a frieze above the scales of justice; one of the misshapen and hairy kidnappers clutching chains hanging from the roof; a silhouetted soldier on his monotonous patrol outside, seen through a spiked grate and a row of sharp spear points; a flaming torch; unnerved slaves watching the interrogation. Stephan shrieks that he cannot stand the pain any more, but Tigellinus’ repeated questions initially yield no results except Stephan’s pleas. Eventually, however, the boy confesses where the Christians are meeting before he faints. When Stephan’s body is brought back up, it is marked with wounds and burns. Our hero Marcus (alerted to the boy’s fate by Mercia) rushes in and asks Tigellinus what he has learned through the torture. The Praetorian lies and says, “Nothing. Unfortunately, he fainted.” Marcus replies, “If he hadn’t, you’d have torn a lie out of him.”

Torture here is more than a convenient plot-point (although Stephan’s confession is necessary to bring Mercia and Marcus’ romance into jeopardy and allow the film to cast their eventual surrender as heroic). To a 1932 cinema audience, the image of an adolescent boy subjected to forced physical pain (albeit off-camera) for the solicitation of information was shocking. It was innocence corrupted in a horrific fashion. DeMille’s crafty decision to have the violence occur in the minds of the audience rather than on screen probably made the reactions even more extreme, particularly since the asynchronous sound of Stephan’s screams are so disturbing in isolation. Beyond the distress inherent in the scene, the fact that it is the evil, pagan Romans who, imitating the later stories of the martyrs, are inflicting torture on innocent Christians, sets up a dichotomy where the distinctly American audience is invited to identify with those on the side of virtue, against those who would utilize the methods of forced interrogation.

Sign, like many of DeMille’s Hollywood films, represents a distinctly American take on the ancient world. One way in which the film subtly underscored this was through the employment of British actors as villains with British accents (i.e., Charles Laughton as Nero) and American actors as the heroes with American accents (i.e., Fredric March as Marcus). Therefore, this film is an early example of the exploitation of 18th century colonial-era constructions and American history to provide subconscious dramatic tension. In fact, even the structures on display are distinguished along American and un-American lines: Nero and his cronies represent a particular monarchical arrangement that is cast as luxurious, brutal, and particularly European, whereas the nascent Christian community is egalitarian, seemingly democratic (with a small d), and hard-working. This association of the Christian protagonists with American virtues allows both ancient people and modern country to claim divine protection and attention in the face of despotism and cruelty.

With such a strong American/un-American binary presented in the film, when Tigellinus tortures Stephan, a very clear distinction is inferred between the twisted definition of “justice” employed by the foreign, autocratic authorities, and that true justice dreamed of by the classless, Americanized, oppressed, Christian masses. Tigellinus’ employment of torture is a very resilient example of what, to a 1932 audience, distinguished “us” from “them”. Christians did not torture, partly because they had suffered at the hands of the torturer at a formative stage of their development. By extension, Americans did not torture because that was the tool of the tyrant, not an enlightened democracy. This was a trope of the country’s founding saga. George Washington expressed this sentiment clearly during the Revolutionary War when, even throughout the darkest days for the young Republic, he ordered his troops not to torture or mistreat prisoners of war taken after the Battle of Princeton:

Treat them with humanity, and let them have no reason to complain of our copying the brutal example of the British Army in their treatment of our unfortunate brethren who have fallen into their hand.

Washington’s goal, and that of John Adams who in tandem persuaded Congress to adopt a war policy of humanity, was to provide a moral victory where torture, argued as incompatible with Enlightenment values and illustrative of Imperial British policy, had no place on or off the American battlefield. Later, the Eighth Amendment to the Constitution (ratified in 1791 as part of the Bill of Rights) expressly forbade “cruel and unusual punishments” for all people (not only American citizens or prisoners of war) that the Supreme Court 87 years later made clear included all forms of torture. This universal applicability of legal rights was certainly a mark of American exceptionalism, and the popular image in the country of the rules of both war and peacetime were repeatedly cast in a patriotic, religious, and humanistic light. During the War of 1812, President Madison evoked the “benevolent policy” of the founding fathers and proclaimed torture:

(an) outrage against the laws of honorable war and against the feelings sacred to humanity… (The avoidance of torture, therefore,) is the spectacle which the deputed authorities of a nation boasting its religion and morality have not been restrained from presenting to an enlightened age.

When Abraham Lincoln signed the Lieber Code in 1863 codifying the wartime operating policy of the Union Army, Article 16 expressly forbade the soliciting of confessions by torture, along with general mistreatment of prisoners. This eventually served as the basis for the Hague Regulations after the First World War, thrusting the proclaimed “American way” of conducting war onto the international stage. DeMille’s audience, both subjected to over 150 years of political history telling them that torture was incompatible with young American democracy, and also conscious of torture’s long history in the ominous world of old Europe, would have watched the Tigellinus and Stephan scene not only with horror, but also a sense of reassurance that what they were seeing was what their country, and their religion, stood in opposition to. It was remote and in the past, overcome in part due to martyrs such as the fictional Mercia and Marcus.

An Inverse of the Pattern: Torture in The Fall of the Roman Empire

Often described as the last of the Hollywood ‘sword and sandal’ epics, Anthony Mann’s 1964 Fall of the Roman Empire attempted to both reinvent the genre and bravely anchor its historical message in a secular, non-religious framework. While far from a perfect result occurred, it is a frequently under-appreciated and neglected picture that nevertheless has salient points to make about a host of modern-day issues including race relations, imperialism, duty, peace, and the politics of fear.

It tells the story of the (premature) death of the cerebral emperor Marcus Aurelius and the ascension of his crazy son Commodus, due in large part to a virtuous general Livius who insists on performing his duty. (The plot was ripped off by, and made less cerebral, by Ridley Scott’s Gladiator in 2000.) Livius does not oppose the succession, although he knows that Marcus Aurelius had actually intended to designate him as his heir. Commodus rules in the exact opposite way of his father, particularly by revoking the permission for Romanized German barbarians to settle on Roman land. This heartlessness shown towards the Germans and a rebellion of the eastern provinces under crushing taxation policies cause a state of emergency that only loyal Livius, as Commander of the Army, can put right. Livius attempts to force Commodus to abdicate, but the emperor bribes army commanders to arrest Livius. He is condemned to death, but Commodus, convinced of his own immortality, challenges Livius to a duel. Livius succeeds in killing Commodus, but other prisoners, including barbarian chieftains, are burnt at the stake under the final orders of Commodus. Victorious but disgusted by the sleaze at Rome, Livius turns down the throne and the emperorship is auctioned off between two wealthy Senators. Against a backdrop of the conflagration and corruption, a final voice over gravely pronounces:

This was the beginning of the fall of the Roman Empire. A great civilization is not conquered from without until it has destroyed itself from within.

The Fall of the Roman Empire (1964), the torture of Timonides (l to r): Ballomar and the barbarians capture Timonides; Ballomar burns Timonides; Timonides refuses to cry out; Timonides touches the statue

One of the most interesting characters in Fall is the freedman Timonides, played by James Mason. In one scene early in the second half of the film, he attempts to reason with a group of Germanic barbarian captives intent on rebelling against Rome. Timonides is a heroic character who strives to persuade by reason and dialogue, in contrast both to Commodus who is ruled by his passions, and to the standard action-oriented heroes of Roman epic films. While trying to present a logical and compelling argument for why the barbarians should lay down their weapons and take up plows as free settlers inside the Empire, he is seized by the prisoners. He is subjected to torture in order to cry out in alarm, and thus cause the Roman guards stationed outside the room to rush in and kill the barbarians. In this way they may achieve a noble death by the sword. Their chieftain, Ballomar, repeatedly holds a torch to Timonides’ bare hand, trying to solicit a reaction. As with The Sign of the Cross, the more gruesome aspects of the torture happen off camera. Ballomar holds the flaming brand just below the shot, allowing the camera to focus on Timonides’ pained expression as he struggles to not cry out and condemn these men to death. Although his flesh is charred again and again by Ballomar, Timonides still tries to reason with the prisoners, and to convince them that freedom is still a choice.

Ballomar then decides that if Timonides touches a carved fetish of the barbarian god Wotan, it will prove that the gods of Rome are weak. Timonides initially refuses to do this as well, but the torture proves too much for him. He reaches out with his good hand, touches the statue, and the torture stops. Immediately, Timonides is horrified at his own behavior and weakness. “I had no intention of doing that,” he says through tears before collapsing. Ballomar, however, is impressed by the strength and character of Timonides and eventually agrees to join the Empire.

This scene challenges the traditional use of torture in Hollywood Roman epic films like The Sign of the Cross. In Fall, the Romans, at least those associated with Marcus Aurelius and Livius, are the good guys. Rome itself is presented on the cusp of an Enlightenment-style era, but it ultimately fails, thus ensuring its inevitable decline and fall. Therefore, it is the uncultured, un-Romanized barbarians, lacking moral strength, who enact torture methods upon Timonides.

In fact, many conventions are turned upside-down in this scene: the Roman is the one who is tortured; the initial objective of the torture is to cause the death of the torturer; the solicited confession is not about information but validation; through his failure to withstand the torture, the tortured wins a victory. These paradoxes and subversions here are typical of Fall’s attempt to break the mold of the Roman epic, and its propensity to offer intellectual explorations of ethical dilemmas instead of more chariot races and sword fights.

The Rome that the emperor Marcus Aurelius attempts to create in Fall is one where all people are welcome and respected, and one that is based on equal opportunity and civil justice. Speaking to an assembly of governors and client-kings from around the Empire, he announces in an early scene:

You do not resemble each other, nor do you wear the same clothes, nor sing the same songs, nor worship the same gods, yet… you are the unity which is Rome. Look about you and look at yourselves and see the greatness of Rome… Here, within our reach, golden centuries of peace. A true Pax Romana. Wherever you live, whatever the color of your skin, when peace is achieved, it will bring to all… the supreme right of Roman citizenship. No longer provinces or colonies but Rome– Rome everywhere. A family of equal nations. That is what lies ahead.

While certainly not the thoughts of a historical second century Roman (even one with as benevolent a reputation as Marcus Aurelius), the cinematic philosopher emperor describes what, to a mid 20th century audience, must have sounded like a liberal, humanistic democracy. Particularly one that, by 1964, had seen the establishment of a body such as the United Nations, heard both President Johnson’s “Great Society” speech and Martin Luther King’s “I Have a Dream” speech, which longed for racial harmony, was grappling with the problem of how to accommodate diverse cultures, and which, perhaps most importantly for the current discussion, was on the brink of being involved in another brutal foreign war in the east.

When Fall was released, full-blown military intervention in Vietnam was imminent. The echoes of the Korean conflict, the other recent proxy war in the east, still sat uneasy in the American consciousness, particularly the brutality enacted on both sides of the 38th Parallel, including torture, mistreatment of POWs, and massacres. Viewers of the film were probably receptive to the idea that those who stood in opposition to Marcus Aurelius’ progressive Romans were the sorts of monsters who would employ torture (even enacted in such an unconventional way). The failure of Timonides only proved the fallibility of such a practice, since when the most intellectual and gentile character of the film is driven to betray his principles against his will, torture is presented as a horrible violation and transgression.

Not Like Us: Torture in HBO’s Rome

In 2002, HBO and the BBC began talks to co-produce a sprawling, epic television series based on the fall of the Republic. Two years later, this eventually became Rome which told, over two seasons, the story of the Civil War of 49 BCE, the dictatorship and assassination of Caesar, the rise and fall of the Second Triumvirate, and the eventual defeat of Mark Antony and Cleopatra by Octavian. Interspersed with the historical narrative were many dramatic storylines involving real and fictional characters, particularly two veterans of Caesar’s Gallic wars, Lucius Vorenus and Titus Pullo. Filmed between March 2004 and May 2005, season one aired in the US in late 2005. A second season aired in early 2007.

From the beginning, the novelty of Rome was that it strove to depart from the standard Hollywood portrayal of ancient Roman culture. By attempting to film historically accurate events and actions, the filmmakers hoped to provide a fresh take on a cinematically familiar world. They claimed they would present the Romans on their own terms, not in the context of modern American society:

Bruno Heller, Executive Producer and Writer: “We knew from the start that if we could stick to historical accuracy as much as possible, we would be getting something fresh, because, generally speaking, Roman movies and TV shows take a kind of pastiche approach to the period. They jumble up all kinds of things from different periods and overlay a modern morality on top.”

Jonathan Stamp, Historical Consultant: “(It is) much more exotic, and strange, and unexpected, and slightly bizarre than the Rome we’ve been given all these years…. One of the things that always happens to you when you start to look at the Roman past is that you get two sensations at the same time, which are apparently contradictory, and they are ‘Golly, they are so like us!’ and ‘My gracious me, they are so different!’ And those two things absolutely coexist. They are different than us because they value different things than us.”

The result was an epic series that tried to give the American (and international) audience a vision of the Roman world divorced from contemporary ethics, behavior, and events. One of the main arenas where this was attempted was in its portrayal of violence, especially torture.

Rome, season one (2005), several scenes of torture (l to r): Gallic prisoners crucified for information; prisoner flayed alive; Evander has his thumbs cut off; Octavian and Pullo torture Evander

In the first series, torture is on display in three main instances. The first episode (“The Stolen Eagle”) has Lucius Vorenus tasked with the impossible responsibility of finding the thieves who have taken Caesar’s standard. When asked by Antony in his tent how he would go about investigating the theft, Vorenus replies, with characteristic matter-of-fact tone, that he would “take captives from every tribe in Gaul and crucify them one by one until someone tells me where the eagle is.” Mark Antony tells him to do so, adding, “I believe there’s a torture detachment with the third (legion), but you may choose your own men if you wish.” The next grisly scene shows several Gallic prisoners being nailed to crosses. The prisoners cry out in pain as the nails are pounded into their hands and their crosses are hoisted up into place. Vorenus walks past, observing the scene with a detached look, silently fuming over his misfortune of drawing this unworkable assignment. Eventually, one prisoner claims to “know where the eagle is.” He gives Vorenus true information about its whereabouts and begs to be let down. Once he has the facts that will propel the narrative forward, Vorenus, to the dismay of the grunt that just spent his time nailing this prisoner up, orders that all the prisoners should now be taken down. The torture achieved its purpose as stated in Antony’s tent, so Vorenus ends it and moves on.

The opening shot of Episode Four (“Stealing from Saturn”) involves the gruesome flaying alive of a prisoner by men loyal to Pompey and the fugitive Optimates. The captive is strung upside down from a tree and, in silhouette, a man steps up to tear flesh from his torso while the prisoner yells. A quick (un-subtle) edit then shows the patrician Scipio tearing a piece of meat from a chicken bone. The commanders proceed to uneasily discuss their situation amid the screaming. The torture is presented as unnerving to most of these men, but necessary. It allows them to learn where some useful lost gold is located.

Finally, one of the major storylines in the first season is Vorenus’ suspicion regarding his wife’s fidelity and the paternity of a new child in his household. In Episode Five (“The Ram Has Touched the Wall”), his friend Pullo and the patrician Octavian decide to interrogate Vorenus’ brother-in-law Evander who they suspect fathered the illegitimate child. They violently kidnap him, bind him, and take him to the sewers. Pullo demands to know if he is the father. A terrified Evander swears by Jupiter that he is not. Pullo thinks he may be telling the truth, but cold-hearted Octavian orders Pullo to start torturing the prisoner. The older man is at a loss because he “never actually tortured anyone… They have specialists (in the army for that).” Octavian suggests he start by cutting off Evander’s thumbs. Pullo begins, and a petrified Evander finally confesses to a love affair with Vorenus’ wife. Octavian, however, is not satisfied and bids Pullo continue. The thumbs are brutally cut off and thrown in the sewer water while Evander cries out in pain. Further sadistic torture finally gets Evander to admit to being the father of the child, and Pullo roughly kills him. The two living men leave the sewers having gotten their answers.

The writers of Rome tried to present a world where the audience was not invited to moralize the characters along the lines of modern ethics, unlike virtually every other filmed Roman epic. Therefore, the torture as depicted was intended to be another example (among many) of how the Romans were “so different” from modern Americans. The writers built upon the already established framework presented by earlier films, including The Sign of the Cross and Fall of the Roman Empire, which utilized the concept of torture as one of the most alien concepts to an American audience. Again, characters with which the audience was not expected to identify (usually a subset, here the entire cast) were the ones who perpetrated the torture. The act itself was extremely violent, foreign to American sensibilities (none of the actors involved were American or spoke with an American accent), and was set up as the cinematically brutal civilization that was Rome.

However, something happened between the filming and the broadcast of Rome that began to alter how the torture incidents in the series played to audiences. Some of the episodes were already into post-production when news began to break about the violence done against prisoners in the Abu Ghraib prison in Iraq. Between April and May of 2004, a 60 Minutes II story and an article by Seymour Hersh in The New Yorker magazine began to accuse Army personnel and private contractors of torturing Iraqi prisoners.

Initially, the rest of the American media did not pay much attention to the allegations, but eventually the story could not be ignored. Seven soldiers (and no contractors) were eventually court-martialed and imprisoned, and the world learned that the torture at Abu Ghraib involved physical, psychological, and sexual abuse (including rape of both male and female prisoners) that was, in some cases, fatal. Nevertheless, what perhaps finally encapsulated the torture at the Iraqi prison for the world was the release of over a thousand photos and even some videos that showed detainee abuse:

“Among the examples of abuse on display in the photos were techniques sanctioned by Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld for use on ‘unlawful enemy combatants’ in the ‘war on terror.’ These include forced nudity, the use of dogs to terrorize prisoners, keeping prisoners in stress positions — physically uncomfortable poses of various types — for many hours, and varieties of sleep deprivation.” (Scherer and Benjamin, The Abu Ghraib Files: ‘Standard Operating Procedure’)

The worldwide reaction to the scandal was loud, forcing even Donald Rumsfeld to decry in public the torture in Iraq as “un-American… (and) inconsistent with the values of our nation,” even though he had previously personally authorized the same techniques for use in Guantánamo Bay, Cuba. The 2013 Senate intelligence committee report on the CIA’s Detention and Interrogation Program during the Bush years (finally released this week) estimated that over 20% of the detainees were probably innocent of any crimes.

This, then, was the charged atmosphere in which Rome screened its first season. Although the depiction of Roman sexual and religious practices continued to be seen as simply “strange and unexpected,” the representation of torture took on a tone that was initially unintended by the writers and filmmakers who produced the series right before the scandal at Abu Ghraib broke, and before the pictures of detainee abuse became so visible. Suddenly, when Vorenus the military officer casually suggested that innocent Gauls should be rounded up and nailed to crosses to solicit information, it was no longer just a consequence of a remote ancient world. One of the most iconic images of the Abu Ghraib scandal showed a man propped up on a box with a hood over his face and electrical wires attached to his outstretched arms, a man placed in this crucifixion-like stress position by a soldier in the Army’s Criminal Investigation Command (CID). When Quintus Pompey and his man Volpe strung up a half-naked prisoner and flayed him alive while their commanding officers sat passively nearby, modern audiences could have been reminded of the many pictures of half-naked Iraqi prisoners in piles and other stress positions, lacerated at the hands of American soldiers, and the obliviousness and slow response of American authorities. When Pullo and Octavian sliced the thumbs off of Evander and killed him, audiences may have seen in their minds a flash of the photos of Specialist Charles Graner and Specialist Sabrina Harman posing over the mangled corpse of prisoner Manadel al-Jamadi:

“Graner and Harman decided to pose for pictures with the body. At one point, Harman gave a thumbs-up sign above the Iraqi’s mutilated face. A close-up shot was taken with Harman’s camera of the dead man’s thumb, which had bruising that Graner said he found ‘out of the ordinary.’” (Scherer and Benjamin, “Other government agencies”)

Despite the filmmakers original attempt to add torture to the pool of “strange and unexpected” customs of the ancient Romans in their program, the Abu Ghraib scandal ensured that the depiction of violence against prisoners (and captured individuals) retained a current and uneasy contemporary significance.

Torture and the Screenwriter

Two main observations in a wider context can be made about these cinematic representations of torture. The first is the general point that in all examples discussed, the torture served a purpose integral to the plot of the movie or television program. In fact, torture may be said to represent an overly simplified screenwriter tool in order to move the narrative forward.

The character of Stephan seems to only exist in The Sign of the Cross so that he may be tortured and betray the meeting place of the Christians. This is accomplished in virtual imitation of a hundred martyr myths in Catholic folklore, reinforcing the theological message of the film.

In Rome, the story of the recovery of Caesar’s standard is one stuffed full with an almost ridiculous amount of chance and circumstance (i.e., in all of Gaul, Vorenus and Pullo just happen to stumble across a band of ruffians who possess not only the standard but Caesars grand-nephew Octavian as well), and the crucifixion of the Gallic prisoners readily offers the name of a (huge) territory in which to search for the missing item. Quintus’ flaying of the prisoner allows Pompey and the Optimates to learn that Caesar does not yet have possession of the treasury, a fact that is then offered up as exposition. Pullo (and the audience) get final confirmation about Vorenus’ marriage troubles through the bloody sacrifice of the character of Evander.

Only the torture scene in Fall of the Roman Empire, perhaps by virtue of the many inversions it performs, offers an episode that is both infused with more meaning than simply a value judgment against a culture, and that represents more than just a tool of narrative. As far as plot mechanics, the ordeal does bring the Germanic barbarians over to the side of Livius, but it also contrasts brutal action against intellect and reason, develops Timonides’ character, highlights the secular temperament of the film in its discussion of religion, and explores the nature of imperialism. Fall’s screenwriters, more so than the others discussed, seem to have utilized the torture scene to communicate several nuanced studies, perhaps because their liberal political agenda and philosophical inclinations urged them to treat such a serious issue in such a complex manner. While no stranger to the Roman epic film, torture has rarely been given intellectual consideration befitting its moral and ethical seriousness as an issue.

The second observation is that in all but one of these instances of torture, the screenwriters have shown torture producing truthful results. In 2006, soon after the Abu Ghraib scandal broke, the Intelligence Science Board, an advisory panel to all American intelligence agencies, undertook a huge study to assess the reliability of torture to provide actionable information. They found:

A variety of factors such as stress, fatigue, distraction, and intoxication can impair the capacity to retrieve and perceive memories accurately. At the extreme, for example, there is a significant social science literature addressing the apparently rare, but disturbing, issue of people confessing to crimes they did not commit. The most critical implications for intelligence are that interrogation tactics can lead the source to provide information that is inaccurate (intentionally or unintentionally) even though the information may seem to conform to the interrogator’s expectations, and also that the process of interrogation itself can affect a source’s ability to recall known information accurately… The accuracy of educed information can be compromised by the manner in which it is obtained. The effects of many common stress and duress techniques are known to impair various aspects of a person’s cognitive functioning, including those functions necessary to retrieve and produce accurate, useful information.

In April of 2009, the reality of an American torture policy re-emerged with the release of Bush-era memos detailing and authorizing torture techniques against detainees, including waterboarding. Once it became a matter of pubic record that many more individuals and government agencies were involved in the torture of detainees held at Guantánamo Bay and in Iraq, some former interrogators took the opportunity to state clearly that such techniques rarely produced any actionable intelligence. A former interrogator using the alias Matthew Alexander admitted on the Daily Show:

I never saw coercive methods [pay off]…When I was in Iraq, the few times I saw people use harsh methods, it was always counterproductive. The person just hunkered down, they were expecting us to do that, and they just shut up. And then I’d have to send somebody in, build back up rapport, reverse that process, and it would take us longer to get information.

FBI Interrogator Ali Soufan testified before a Senate Committee in May of 2009 and explained why he was against the use of torture:

(Torture methods are) ineffective, slow and unreliable, and as a result harmful to our efforts to defeat al Qaeda. This is aside from the important additional considerations that they are un-American and harmful to our reputation and cause.… I interrogated Abu Jandal. Through our interrogation, which was done completely by the book (including advising him of his rights), we obtained a treasure trove of highly significant actionable intelligence… This Informed Interrogation Approach is in sharp contrast with the harsh interrogation approach introduced by outside contractors and forced upon CIA officials to use… (which) tries to subjugate the detainee into submission through humiliation and cruelty. The approach applies a force continuum, each time using harsher and harsher techniques until the detainee submits…. It is ineffective. Al Qaeda terrorists are trained to resist torture… This is why, as we see from the recently released Department of Justice memos on interrogation, the contractors had to keep getting authorization to use harsher and harsher methods, until they reached waterboarding and then there was nothing they could do but use that technique again and again… A second major problem with this technique is that evidence gained from it is unreliable. There is no way to know whether the detainee is being truthful, or just speaking to either mitigate his discomfort or to deliberately provide false information. As the interrogator isn’t an expert on the detainee or the subject matter, nor has he spent time going over the details of the case, the interrogator cannot easily know if the detainee is telling the truth. This unfortunately has happened and we have had problems ranging from agents chasing false leads to the disastrous case of Ibn Sheikh al-Libby who gave false information on Iraq, al Qaeda, and WMD.

The Los Angeles Times reported in June of 2009 that Khalid Shaikh Mohammed had admitted to offering false information to his interrogators despite being waterboarded 183 times in a single month. A 2006 study explored the scientific evidence for the reliability of torture and not only found the technique to be wildly ineffective, but also argued torturers, lacking a knowledge of the truth (since that is, after all, the reason for the torture), are unable to recognize the legitimacy of any confession made under duress, therefore invalidating it as a useful information-gathering practice. The recent 2013 Senate Select Committee report confirmed that torture under the Bush Administration did not produce results agents could use. Therefore, professional interrogators, social scientists, congressional staffers, politicians, and the victims of torture themselves all agree that in the real world, the goals of torture are routinely not met.

Why then, in virtually every case of torture committed to celluloid is torture represented as a successful practice? If we put the possibility of lazy scriptwriting aside, the reason why cinematic torture is useful in these cases may be related to what Political Science professor Darius Rejali calls its “dark allure.” It taps into our desire to dominate and get one’s way regardless of the will of one’s opponent. It suggests that it is possible to force a reluctant individual to offer up information that he is keeping to himself through the violent implementation of pain. And this method promises to accomplish such a victory quickly and completely given the fact that most humans do not like to experience pain. That is what is driving nasty Tigellinus, frustrated Vorenus, and the vicious pair of Octavian and Pullo. None of them are disappointed by the results (or even adversely affected by their participation in the practice). In each case, the screenwriters reinforce the fantasy that torture is essentially harmless and that it works.

Again, it is Fall of the Roman Empire that confounds the pattern. The outcome Ballomar receives is initially not what he wanted (the noble slaughter of his soldiers), so he is forced to change his request (to touch the statue). Timonides breaks under the torture (as every other victim we have seen does), but his actions are false. “I had no intention of doing that,” he says after laying his hands on Wotan. The most ethical and moral character in the film is made to do anything when subjected to excruciating pain. He is moved by torture to perform an act that is empty and, interestingly, causes the torturer to invalidate the action, exhibited by Ballomar’s change of heart and rejection of the Germanic gods. It is the victim of torture who finally enlightens his tormentor. Torture here is portrayed more in line with modern evidence as offered by Ali Soufan and others– as an act that debases the perpetrator and ultimately yields no useful results.

Before the Bush Administration approved the techniques of torture regarding the interrogation of prisoners (including at least one US citizen) in American custody, and before the actions of the personnel at Abu Ghraib became public knowledge, torture was one of the easiest ways, along with “deviant” sexuality, to underscore the difference between Rome and America, and warn what America could become if it followed Rome’s example. When depicted on the screen, it became a way to elevate modern Americans above the cruel inhabitants of the past. It also, however, perpetuated the fallacy that such vicious interrogations work, a myth that seems to have also been widespread and persistent in the Roman world. Today, these scenes are seen through different eyes than those that originally watched. No longer can the torturers be simplified as “them.” Each cinematic depiction raises an uncomfortable (for a majority of Americans at least) specter of our recent past.

A Response and Departure

In the second season of Rome, broadcast in 2007 after the Abu Ghraib and Guantánamo revelations, one screenwriter put in a single episode (“The Tortoise and the Hare”) two very graphic depictions of torture. The first involves the extraction of information from the slave boy Duro who is suspected (correctly) of trying to poison the noblewoman Attia (who calmly, almost detached, watches the torture). It is the explicit teenage torture scene that The Sign of the Cross spared us. While bound, the sixteen year-old boy is whipped to a bloody mess by Timon, Attia’s henchman, then hot plates are applied to his lacerated skin. Reference is made explicitly to the historical fact that to make a possible legal case, Duro, as a slave, has to be tortured (although the script then has him killed off quickly once his short narrative purpose is dispatched). Attia’s daughter Octavia, when she sees what is happening, says explicitly, “This is wrong in so many ways.” Later, in the same room in Attia’s house, the woman who Duro identified as behind the assassination attempt, Servilia, the patrician mother of Brutus, is also whipped and raped. It is done to solicit a confession (as well as vengeful acquiescence and humiliation), although proper judicial authorities are not present. Before the torture, Servilia tells Attia, “You think it’s me you degrade now, but it’s not — it’s you. As long as you live, you will feel degraded and defiled by this.” The mother of Brutus undergoes horrific flogging, but Timon is finally pushed too far with this bloody torture. He refuses his orders and lets Servilia go. Angrily, he grabs Attia’s throat and screams, “I am not an animal!”

Rome, season two (2007), the torture of Attia’s enemies (l to r): Duro strung up and tortured; Servilia bloody from torture; Timon rejects the role of torturer; a degraded Attia

It is worth noting that these two scenes from the second series of Rome are completely removed from a military context, unlike the torture scenes from the first series. The victims are not men of soldier age, and they are not part of the larger political world. Instead, both are presented as pawns in the private battles of merciless Attia. Timon, the torturer, is shown disobeying orders when the stress of the torture becomes too much. Only by stopping it can he regain his humanity. The screenwriter here seems to be both making sure that these post-Abu Ghraib depictions of torture do not evoke that scandal, and possibly even comment on what any one of the indicted soldiers or officials stationed in that prison could have done to end the abuse. However, the screenwriter still seems unable to break the habit and allows the torture of Duro to produce a true confession, while at the same time allowing Servilia to stoically resist the shocking violence done to her person and remind Attia that using torture will only, ultimately, degrade the torturer.

On a historical level, we are not Rome. In the realm of cultural representations, however, whenever the Romans are employed, we have traditionally striven to compare or distinguish ourselves from them. Cinematic Rome reflects back our hopes, fears, and unease at our global role, the successor empire of the West. Many diverse voices have claimed that because of the Torture memos and the conduct of American authorities toward enemy combatants and prisoners, the US has lost not only its ethical sense but also its moral standing in the world, abandoning the carefully constructed defenses against torture formulated by Washington, Adams, Madison, Lincoln, and others. I would suggest that we have also lost our ability, carefully constructed by Hollywood throughout the twentieth century, to be shocked by a civilization, ruled by overbearing violent principles, which inflicted torture on its populace, prisoners, and sometimes citizens. On the screen, we see ourselves now where before we saw only monsters, strangers, and barbarians.

New York City, December 11, 2014

★★★ Light! Feeble light maybe by ordinary standards, but warm-toned and heartening after the unremitting darkness. A little rim of snow held on to the neighboring balcony and snow whitened the planks of the scaffolding down across the street. The sky was still overcast, but thinly; light shone down even to the subway tracks. The clouds thickened till the sun was a white dot. Then the sun was a larger white patch, and then something like sunbeams came through the windows.

Two Decades in Comedy's Best Writers' Rooms: A Conversation with John Riggi

by Matt Siegel

John Riggi has written for, among many other shows, The Larry Sanders Show, 30 Rock, and the first and second seasons — nine years separated — of HBO’s The Comeback. He spoke with us about his two decades in the industry: about how TV writing has changed; about how TV writers have changed; about working in the industry while gay, then and now; and about coming back, again, to HBO.

My way into television writing was so atypical, because I started out as a standup and that’s what took me out of Ohio to Chicago. I started working a lot at the Improv in Chicago, and I met a lot of L.A.-based comedians there and one of the main ones, strangely — I say because of our different political leanings — is Dennis Miller. We worked together for a week and really kind of keyed into each other, and he was very interested in me and he just kept saying you’ve got to move to L.A., you’ve got to move to L.A., and so I did. He had said he was potentially going to get this talk show, and would I be interested in writing on it, and I said sure.

I wasn’t really interested in political humor, so I kind of pushed through the idea of doing these desk pieces that became longer and longer and more complicated and became little narrative pieces. And then that show got canceled after eight months. I had read for a part on a show that Garry Shandling was doing called The Larry Sanders Show, and I got the part, and then through a very long story that isn’t important, I ultimately didn’t get the part. The Larry Sanders Show was just about to start up at the same time that The Dennis Miller Show was canceled, so I wrote a script, and I didn’t know what I was doing; I had never written a script before in my life. My script got to Garry and I went in and had a meeting, and then heard nothing, and was kind of giving it up. And then I met him at Campanile [a Los Angeles restaurant] where HBO was having a party for the Cable Ace Awards. My One Night Stand for HBO (a now-defunct stand-up comedy series) was nominated for an award, and my husband David said, “Put your tux on and go down to Campanile and find Garry and talk to him about this job.” So I did, and I finally got to Garry, and he said, “I’m just really worried; I’m not sure you’ll be happy being a writer on The Larry Sanders Show because you wanted to be an actor,” and I said, “I just want to work on it — I don’t care.” And that was on a Sunday and then that following Wednesday I got hired.

What was your brand of humor?

It was very long form, like I didn’t really have jokes. One time I got this gig where I got to open up for two weeks for Diana Ross in Las Vegas and I was so excited. The first night I did it I bombed terribly, and I realized that the Las Vegas audience didn’t want to get to know me, they just wanted me to do some jokes and get off, and so I went back to my room that night and thought, “What setup punchline jokes do I have?” So I just extracted everything else that wasn’t a joke and just went out and told jokes for ten minutes and it went much better.

Your first writers’ room was Dennis Miller. Was that a boys’ club?

Yes, the only woman was Leah Krinsky, but it was an amazing writing staff. It was Max Mutchnick and David Kohan (creators and Executive Producers of Will & Grace), it was Eddie Feldman, it was Kevin Rooney, it was Drake Sather, it was Ed Driscoll, Steve Rudnick and Leo Benvenuti — people who went on to do a bunch of different things.

Was gay okay in that writers’ room?

It was okay — I don’t think it was necessarily prized in any way. I don’t think it was like, “What’s the gay perspective on this joke?” I don’t think that ever happened. I don’t think that’s ever happened to me quite frankly…maybe on The Comeback.

Writers’ rooms, to me, don’t necessarily seem like a “safe space,” so where was your comfort level during Dennis Miller?

Oh my god, I’m just realizing that I don’t think I was out yet. I wasn’t out. So my comfort level was really bad. Like I remember one time — I don’t know why he did this, I can’t remember the circumstance — but we were looking to move to this guesthouse in Silver Lake — me and my boyfriend at the time. And for some reason Dennis [Miller] came with me to look at this place, and I remember that I went to work wearing black bicycle pants and Doc Martens and some kind of weird t-shirt, and I remember we were walking up the steps to look at this place, and I remember Dennis going, “Reej, what’s going on with the outfit? What, are you going gay on me?” I remember him saying that and I was like “No, no, what are you talking about?” So my comfort level was not great as far as that goes. Like I was very much a part of that [writers’] room and I was appreciated for what I was bringing to the table comedically, but I was not at all talking about my personal life.

So you flew under the radar in terms of passing as straight.

Yes, surprisingly.

But, could one be a big ol’ queen in a writers’ room in 1991?

I don’t think — not on that show. I don’t think so. I think it was too — I don’t think it would be overt, but I just don’t think it would work. I don’t think it would work.

So, you went from Dennis Miller directly into writing for The Larry Sanders Show. Did you feel more secure as a writer at that point?

No, I felt like I jumped in the deep end of a swimming pool — I knew what that show was. I mean, almost immediately I realized that I was working in an environment where the bar, writing-wise, was so high that it was a little bit intimidating. Garry taught me the kind of writing that I like the best, which is writing about human behavior that’s funny as opposed to writing jokes. I can write jokes, and I do it for a living, but, like, Garry used to say to us all the time, “Write the behavior and then figure out what’s funny about the behavior.” I’ve never forgotten that and I think it’s really good advice, but it’s also really hard — that’s why people write jokes.

Even then, as green as I was, I remember watching us shoot stuff, and I remember thinking, “Oh my god, I’m seeing something that is above the level of what most shows are.” Just the level of those guys like Rip [Torn] and Jeffrey [Tambor]. They were such good actors.

What was the Larry Sanders writers’ room like?

It was a little different. We wouldn’t gangbang a script or punch up a script together — the show didn’t work that way. Everyone considers Larry Sanders to be a single-camera show, and in the sense that we didn’t have an audience, it was single-camera, but we were shooting three cameras all the time, which Todd Holland really pioneered, because when he got there it really was single-camera, and Todd was like, “This just needs to go faster and we need to shoot quicker,” and so we shot The Larry Sanders Show in two days. We’d shoot on Thursdays and Fridays and we’d shoot like seventeen pages a day, which for a single camera show is unheard of. Basically the way it would happen is we’d have a script, we’d do the table-read on Monday, we’d take the script back and a small group of people would rewrite it, and then it would go back out on Tuesday. And then on Wednesdays, the script would come back up from the floor and it would have improvised new lines in it and then I would say yay or nay to them. Sometimes Garry would say, “I want this one in for sure. Put that in.” So my work Wednesday nights was to put those improvised lines in — or not — and then we would shoot Thursday and Friday.

At the same time, you were actually writing about an actual writers’ room on both The Larry Sanders Show and The Comeback. Is there an evolution between the way you wrote the writers’ room on The Larry Sanders Show and the way you wrote the writers’ room on The Comeback?

I think the writers’ room depicted on The Comeback, honestly, was a more realistic representation of probably what happens in a room in general. First of all, on The Larry Sanders Show, very seldom did we do stories that revolved around the writers. It was basically that triad of Hank, Larry, and Artie, and the writers would move in and out of those stories. When we did The Comeback, the idea that writers have a sort of love/hate relationship with the people that are in the show, I think is a very common thing. So we kind of took that to the extreme with Paulie G. [the name of the showrunner character on The Comeback], but I think that room is pretty typical of what you might see on a sitcom because it really is a boys’ club — it really is. When I worked on Will & Grace, that was the gayest room I’d ever been in in my life, and it was sort of the antithesis of every other room I’d ever been in. We had every gossip rag out there in the middle of the table and that’s what we would do host-chat with — we would go through the gossip rags and talk about them and I’d never seen that.

Host-chat?

Host-chat is a thing they called it at Will & Grace, which I’ve sort of taken up, which is before you dig in for the day. Like, if 10 o’clock is the start time, the writers walk in and everyone has a cup of coffee and a bagel, and before we jump into the work, there’s a thing called host-chat, where basically you just kind of get your motor going. But I’d never been in a room where there was like US Magazine and People and OK! on the table, and there was a large presence of gay writers in that room. Also, the other thing, by the time I got to Will & Grace, that show was running like a machine — it had been on for seven years, and so the room was well-established and ran pretty well.

When people ask me what it’s like to be in a writers’ room, I always say that it’s like every day you go to a dinner party and the dinner lasts for twelve hours and you have the same six friends and you’re all talking about the same six friends. You spend an enormous amount of time with these other writers. If you start a brand new show and those eight or ten writers walk into that writers’ room and they look at that table and they all take a seat, once they have sat in those particular seats they never give up those seats, so things get territorial.

It’s very communal and it’s very very interactive, and there can be a great writer in there but he or she might just drive you out of your mind for whatever reason. And there’s a weird thing of knowing when to talk and when not to talk, are you talking too much or are you not talking enough, are you pitching too much or are you not pitching enough — there’s all these various things to keep in mind.

And people judging what you’re saying.

Yeah, it’s a very judgy room. Like I’ve always heard the Frasier [writers’] room was almost silent because unless you were absolutely one hundred percent sure that the thing you were about to pitch was a home-run, you did not say it because otherwise you were shamed. So I’ve always heard — again it could be just a rumor — the lore that Frasier was a very quiet room.

Is there any difference between the writers’ rooms of the early nineties and the writers’ rooms of today?

I think the writers — I don’t know if I want to say this. I will say a couple things. I will say that writers are dealing with an audience that is much more savvy about what they’re watching, and secondly, a dwindling audience. I’m sure when sitcoms were first invented it must’ve been great to be working on them, because nobody had ever seen anything yet, so everything was new and everything was fresh. I Love Lucy was in the fifties so now we’re almost seventy years later — what are we supposed to invent that’s new at this point? What haven’t they seen? In a way I think it’s good because I think it makes you write more about characters. I also think — I guess I will say — I think that some writers today, at least it has been my experience recently — that I have worked with writers who don’t in my estimation fully understand the process and what’s involved in running a show and putting a show together and making a show. I’ve had experiences with writers where there seems to be a kind of naiveté about how writers’ rooms work, what’s expected of them, how hard they should be working — just stuff that I would never do. I’m gonna sound like an old man but I’ve had experiences with staff writers coming in and being like, “Can I have tomorrow off because my sister’s having a birthday party for my nephew and I kind of want to be there,” and it’s like, we’re shooting tomorrow.

Entitled.

Yes. Entitled. Entitlement. For sure.

The character of Gigi on The Comeback is an archetype for the young over-educated east-coast playwright genius who is recruited to write for television. Does that happen?

Yes. As writers we kind of go through these cycles of “Who’s out there whose interesting and isn’t doing the same old thing?” and so a lot of times you do get playwrights, and in theory that sounds great, but sitcom is such its own little weird animal — totally 100% weird. This is not a disparaging remark about playwrights; sitcom writing is just a weird writing form. You really have to keep so many things in your head. Like right now we get like twenty-one minutes to tell a story on a network sitcom. So if you have an “A” story and a “B” story, that means both of your stories are ten minutes long. And if you have eight characters, how long are they gonna be on screen for, like a minute each? So the idea of Gigi was that Gigi was a smart interesting writer who basically got thrown into the lion’s den of this boys’ club of comedy writers because we’re tough as a group. I would say you have to have a pretty thick skin in a writers’ room.

For me, being gay, I mean you hear a lot of gay jokes. You hear a lot of jokes that you kind of sit there and go, “Really? That’s the thing?” I remember one time I was in a room and I was wearing a flowered shirt and the showrunner said to me, “See, that shirt I could never pull off because it’s got flowers on it.” And I said, “So?” And he goes, “Well, you know, you’re gay so you can wear a flowered shirt, but for me it’d be hard to wear a flowered shirt. What are people gonna think?” And I’m like, “What, they’re gonna think you’re gay?” I remember it making me really angry. I remember thinking, “Buddy, if all that’s stopping you from sucking a dick is a flowered shirt, put the shirt on.” So the idea of Gigi was to see what would happen when you put a female writer in a room full of comedy writers who were used to getting swiped at all the time, and she wasn’t. That part of that writers’ room depicted on The Comeback was a real thing. It was something all of us had experienced: Michael [Patrick-King] had experienced it; I had experienced it.

Which part?

A writers’ room can be very tough. Everything is questioned. Everything is potential to go after you. You could come back from Thanksgiving and someone could go, “Oh, well, somebody was eating turkey.” You just have to steel yourself because you walk into the room and they’re comedy writers, so, as comedy writers nothing is off limits. Nothing. And depending on what mood you’re in on any given day, you might find it really funny or you might be going, “Hey, you know what? Fuck you. I’m not in the mood to hear your bullshit today.” So, even a normal comedy writer can have that perspective. So what happens when you amp it up and make it a female playwright who has no idea what that world is like? So, we basically sort of fed her to the wolves just to see what would happen.

And in these rooms everyone is always “on.”

Yes

That must be annoying.

It’s exhausting. It’s exhausting.

I assume you don’t feel the need to be on all the time after twenty-plus years in these rooms.

Well, there’s a herd mentality. It’s like if you’re not on, what are you doing? I think the nervous feed is, “Yeah, but if I don’t have a room bit or I don’t have a thing maybe the showrunner won’t think I’m paying attention or won’t think I’m engaged and maybe he won’t like me or he won’t think I’m doing a good job or that I’m not one of the guys. So you can very easily get pulled into it. I didn’t really care because I was like “whatever.” But I don’t fault people for doing it. I’ve seen it over and over again where people are like, “I gotta play the game here.” And depending on who the showrunner is, you have to keep them thinking you’re paying attention and you’re engaged and you’re a fun guy. Sometimes it’s like you wanna be in the room when they’re breaking a story, and if the showrunner suddenly has decided that you’re not one of the fun ones, you get put in the joke room. So now you’re in the punch-up room, now they’re in the main room coming up with the next five episodes, but you didn’t get picked because you don’t have a funny bit that anybody likes. That does happen.

Tell me about the writers’ room for the second series of The Comeback.

The Comeback “room” was Michael Patrick-King, myself, Amy Harris, and Lisa Kudrow — that was it. That room was great. It was kind of a distilled version of the first series of The Comeback where there were a few more writers. But at the time we were only contracted to do six episodes so Michael decided — and I don’t think it was a bad idea — to say, “Let’s just let it be the four of us.” That room works in a completely unique way in that we start talking about scenarios and it’s easy to stay engaged because Lisa starts doing [her character] Valerie. So it’s like what would Valerie be doing, and then Lisa does Valerie, and then you start talking to Valerie, and the scene starts coming out, and the writers’ assistant is just trying to take it all down because it’s just all happening in the moment and it’s very exciting and it’s very cool. I’m the biggest fan of Lisa’s. It’s hard to work with someone who you’re that big of a fan of sometimes, especially when you have to direct them.

And the storytelling of The Comeback is completely its own thing because, to me, it’s like TV story-telling pulled inside out because in regular TV you write a world where people are just going through their lives, and that’s a world, and they live their lives, so you write it like they live their lives. In The Comeback, every single person knows that they’re on television, so that’s always on their minds. And the number one person who never forgets it, who ultimately probably can’t live without it, is Valerie. And so coming at writing her character from the perspective of saying, “I constantly know there’s a camera right there,” is very unique and unlike anything else I’ve ever done for sure.

We all know each other; I’ve known Michael forever. We’re also four really passionate people about the show — first and foremost, Michael and Lisa because they’re the ones who devised it and came up with it. But Amy and I came on board in the first season and that show is so important to me and I never forgot it. As a matter of fact, when I just heard inklings through this back channel that The Comeback was gonna come back for six episodes, I emailed him [Michael Patrick-King] and said “Please tell me that I’m involved.” So we would have just vigorous discussions about the show and where the show could go. The first time we did The Comeback, people liked it but they would say to me, “I don’t know what I’m watching,” because people forget it was nine years ago — almost ten years ago — and reality television, people didn’t really even know what it was. So now it’s almost ten years later and now it’s like, “Where is Valerie with reality television?” That was a big discussion among the four of us.

Valerie is not the same in regards to her knowledge of what that camera is doing to her for every second that she is on it — she’s much more savvy about it. And so we tried to make it feel like nine years has gone by and Valerie, like the general public, understands what reality television is a lot more, and what it can do to you, and how you can manipulate it for what you want it to look like. But that writers’ room was a dream because it was four people and it was very intimate, and it reminded me in a way of doing radio in the sense of like, “Is anyone listening to this? Is anyone ever gonna see this?” That’s how I would feel. I would feel like we were just sitting around talking and having fun and just laughing our asses off, and sometimes arguing about what we thought the show or an episode should be, but mainly laughing. And it was so much fun, I was like, “Are we actually really gonna do this, or is this just like us having a party?” And then we got into the shooting and it was not a party. It was an incredible amount of work in a very short amount of time.

Was this writing experience like the pinnacle in terms of the harmony in the room? Nobody’s having to kiss anyone’s ass; you’re just creating. Does it get any better

It was very free in that sense. Listen, I love The Comeback, it’s one of the high points in my career without a doubt. I also know that people are very polarized about it — people either really like it or they go, “Oh my god, I can’t watch it. It makes me cringe.” I see this thing all the time, “cringe-worthy” in the press, and all I can say is that I have a completely different experience with it, and maybe it’s because I have the benefit of seeing Lisa cut the character and we all start laughing, like I’m always always aware it’s not real — it’s Lisa doing this character that we all think is hilarious. And that’s not to say that I haven’t been moved — Lisa has made me cry playing Valerie while we’re shooting, so I get it. But for whatever reason, this “cringe-worthy” phrase to me is always pushing it beyond the limit of what I even thought it was. I guess I just don’t look at it that way, but I do absolutely look at it as one of the pinnacles of my career.

But I have to say that 30 Rock, for me, when we won the Emmy our freshman year, that was unprecedented. I mean, I remember that moment…and I remember us going back into that writers’ room in the second season and now we all had an Emmy.

We were such underdogs, so for us to win was a big thing. So I have to include 30 Rockbut the great thing about The Comeback is that it’s probably as close as you can get in television to a one hundred percent labor of love. I think it’s a labor of love on Michael’s part, on Lisa’s part, on Amy’s part — everybody — even HBO. I think those guys loved that show so much that they just wanted to bring it back and see what would happen. And the other great thing about HBO is that they just let you make the show, they’re very very hands-off.

For me, I love that character [Valerie], and I always say that I could write Valerie till the day I drop dead.

Top photo by Rubenstein

Anecdotal Knowledge Of Female Desires Affirmed

“All I’m gonna say about that is, I don’t know one girl who doesn’t want to be a girl in a country song. That’s all I’m gonna say to you. That’s it.” [Via]

Life Bad, Book Good

“Jacobson’s earlier novels have been compared with some frequency to Philip Roth’s. That’s been easier to see in books like ‘Kalooki Nights’ and ‘The Finkler Question,’ which borrow against the restless sexuality of the 1950s and Zionist politics, respectively. It’s harder to see Roth in the thrilling and enigmatic refractions of ‘J,’ whose subtle profundities and warm intelligence are Jacobson’s own. But in its bracing recognition that some conflicts are irresolvable, as is conflict itself, there is something of Roth, I think. So too in the stoical acceptance (if that’s what it is) of the book’s brutal conclusion. ‘J’ is not a joyful book, by any means, but its insistent vitality offers something more than horror: a vision of the world in which even the unsayable can, almost, be explained.”

— If you still read novels, Howard Jacobson’s J

is a novel you should read, particularly if you would like your belief in our inherent terribleness reaffirmed.

The Convergence of the Dude

by Alice Hines

Illustration by Katie Barnwell

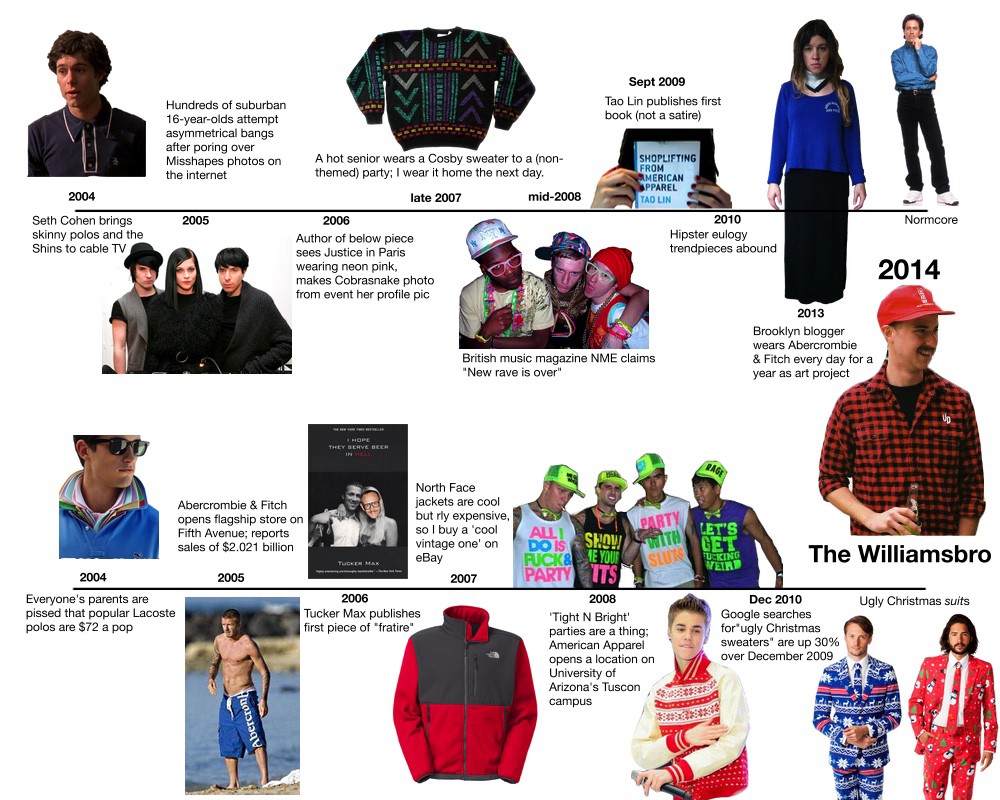

Last week, the internet found the Ugly Christmas Suit, a polyester three-piece that made the ghosts of ugly Christmas sweaters past look like tasteful cardigans. Among the numerous write-ups was a two-fists-up review from Total Frat Move, the website responsible for the #TFM hashtag (used 108,000 times on Instagram). “This suit is for getting drunk and hitting on your boss’s daughter when he’s right in front of you. This suit is for attempting to snowboard in an urban area. This suit is for falling into the eggnog bowl,” it advised.

The Ugly Christmas Suit was designed by a company in the Netherlands, but it’s clearly appealing to an American niche. That’s the crowd who, for the past few years, have turned Ugly Christmas Sweaters into $80 purchases and the streets of NYC into debauched mosh pits of drunk Santas: bros who love to dress up.

Yes, bros who love to dress up. Once known for khaki pants and New Balances, bros are becoming increasingly experimental with their fashion choices. Look through hashtags and blogs linked to Greek culture and you’ll see it: rushers in head-to-toe ’80s leopard prints, muscled ravers at EDM concerts, college football players with retro facial hair. At the very moment when “normal” is trending on net-art Tumblrs, loud self-expression via clothing is dominating frat parties from USC (Trojans) to USC (Gamecocks).

Let’s call them the Williamsbros.

The Williamsbro is king at Christmastime, and Santa Con is his throne. This Saturday, more than 1,000 people, mostly young white men, will gather in New York in outfits no one else but paid mall Santas wear. The most creative will get high-fives for their light-up sweaters or extra-fluffy beards. The event brands itself as countercultural: in a recent statement, organizers called it “culture-jamming” that “pokes fun at society and the overly-commercialized aspects of the holiday.” Yet there’s something about Santa Con that’s in line with patriarchal power structures, from the binge drinking to the sexual harassment to the in-your-face celebration of the world’s most traditional holiday.

The Williamsbro’s clothes are weird, but his message is not. The fun of them lies in eliciting reactions from the outside world that don’t trip up conventional power dynamics. Dressing for shock originated in movements like punk, where weird clothing signified radical thought. When a fraternity throws a Tight-n-bright party and all the guys wear Spandex neon, though, they’re just being funny. If anything, the pseudo-gay clothing only illuminates the hetero-ness of its wearer.

The bro of yore dressed up for toga parties. The Williamsbro brings the toga party, ’80s party, and Christmas party to wherever he is by virtue of his clothing. “Whereas most people will spend one night in an ugly Christmas sweater, I make them my entire seasonal wardrobe,” a TFM writer wrote in a 2011 post, “Aggressively Celebrating Christmas.” “I also put wreaths on everything, and I mean fucking everything. Police Car? Wreath. Sad hobo? Double wreath and tinsel.” This is satire/fratire. The Williamsbro’s favorite joke is that the ridiculous thing he’s doing isn’t actually a joke. His costume isn’t a costume. His convention mocking Christmas is about celebrating Christmas.

Shinesty, the Boulder, CO, company that’s the top US vendor of the Ugly Christmas Suit, first marketed its collection of “rare and outlandish clothing” for theme parties. But according to Chris White, the founder, people are wearing the clothes on a regular basis. “You might buy something because it’s ironic and funny, but the line is blurred. If you wear it five times in a row, is it ironic? Or do you just think it’s cool?”

Shinesty didn’t set out to cater to a specific demographic. “People have called us both hipster and bro, which I think is indicative of a larger trend,” White said. “No one wants to wear a plain black Northface from the early 2000s. They want something unique.” In addition to this suit, Shinesty stocks all manner of Aztec print hats, ’80s ski-suits, Bill-Cosby sweaters, fanny packs, and windbreakers, a mix of vintage and new. It’s a collection of items that could be spotted anywhere from an East London club night to a Sigma Phi ’80s party, but basically no where in between.

Are we approaching the young white male singularity? Several new types pose the question. The modern “alt bro” is a privileged male whose surface-level intellectualism masks immaturity and misogyny. The tech bro, meanwhile, pursues conventional career success while appropriating hippie and burner aesthetics. The hypebeast, too, sits in the crosshairs of hip-hop, fashion, and bro cultures.

Are any of these really different? Or are they just part of one all-inclusive expanding bro universe, united by privilege? If so, we’re not quite there. This year, one area where Santa Con will not be headed is Williamsburg-adjacent Bushwick. Organizers had plans to congregate there for the first time, but backed off after a local public outcry.* Protesting the Williamsbro, it seems, is the last best way to distinguish yourself from the Williamsbro.

*And, just yesterday: “Due to the planned protests on Saturday, Santacon is scaling back this weekend’s festivities in order to create the lowest possible impact on the city we love.”

A Poem By Tomás Q. Morín

by Mark Bibbins, Editor

Extraordinary Rendition

for Philip Levine

When the CIA said, An extraordinary rendition

has been performed, I knew Lester Young

blowing his saxophone in that way he did

when Billie Holiday was a few feet away

smoking, singing “I Can’t Get Started,”

was not what they had in mind. No, the agent

at the podium talking to reporters

who spends most of his days staring

at computer screens riddled with numbers

and names and maps of places he’s never been

probably thought of a man in a hood

far from home swimming

in a room flooded with questions.

If the agent had children

to pick up from school after work

maybe he thought, in spite of his training,

of the hooded man’s daughter waking

to find her father gone, her mother

in pieces. What might never cross his mind

is how sometimes that same girl

or any one of a hundred others

might be imagining him