Maybe You're Sad Because Your Job Sucks

“New research suggests a strong link between being disenchanted by work and depression. City College of New York psychology professor Dr. Irvin Schonfeld studied more than 5,500 school teachers to estimate the prevalence of depressive disorders in workers with burnout. He discovered 90 percent of the subjects identified as burned out met diagnostic criteria for depression.”

New York City, December 16, 2014

★★★ Heavy dampness or a thin mist was on the air, fading the colors of distant buildings. The gray morning clouds thinned out to blue patches in the early afternoon, and the sun cast shadows. Mourning doves perched on looping razor wire overlooking the edge of the roof deck. Lower Manhattan had flattened into a whitewashed silhouette. Beer cans floated in a tub of still water, innocent of ice. By commuting time, a shower had come and gone, leaving puddles to reflect the overhead fixtures of the shops. Water clung to the sides of the D train. Up between 66th and 67th, where scaffolding had darkened the sidewalk for long months, the lingering damp on the air caught the light from the decorated street trees and created a luminous corridor.

Dog Versus Baby

I have owned a dog for my entire adult life — more properly, a Chihuahua. First, there was Sal. Then, for a brief period, there was Sal and Penny. Since 2007, it’s just been Penny. (RIP Sal.) Both Sal and Penny, despite their temperamental differences, have always been treated like actual family members. We rarely leave Penny at home while we vacation or visit family. And, like family, we have made great allowances, and often, excuses, for her misbehavior.

Anyone who knows Chihuahuas will be unsurprised to hear that Penny is abnormal for a dog but fairly standard for a Chihuahua. She is sweet and cuddly and playful. She doesn’t even mind strangers, once it’s clear they are staying for a while. She easily adapts to hotels and new houses and new people. But, her list of dislikes, or, more properly, things she cannot tolerate, is long: other dogs, birds, squirrels, loud noises, strollers of any sort, doorbells, delivery people of any sort, and of course, babies and small children.

Now, Josh and I would both admit, I think, that some of Penny’s failings are our fault: We never taught her much. She doesn’t know many tricks, though she is very intelligent. She isn’t obedient in any way at all, and we never successfully learned how to deal with her nerves. Which, was, in hindsight, a grave oversight.

We worried a bit, when I was pregnant, about what it would be like for Penny. “The dog is just as important to us as the baby,” we told ourselves, because we LOVE this dog and didn’t have a baby yet, so we didn’t realize how silly it is to say or think that. We felt confident that the dog and the baby would get along just fine. And at first, they did. We were so proud of Penny. Zelda, who didn’t seem to be aware of the dog’s existence for several months, was an object that Penny seemed instinctually to want to protect. She would lie on the threshold of Zelda’s room, as if waiting for intruders. When the baby cried, Penny’s ears perked up and she ran to whatever container the baby happened to be currently contained in. Whenever we let her near the baby, she sniffed her quickly, stealing a whiff, before backing away, head cocked, trying to make sense of the being now living with her.

Of course, Zelda wasn’t really living yet. Sure, she was a huge draw on my personal resources, but it was probably better than ever for Penny, at first: Zelda wasn’t much of a crier, she slept a lot, and so suddenly, I was at home twenty-four hours a day, quietly sitting in one place while Penny slept nearby. This is, as far as I can tell, Penny’s most desirable life scenario: to just chill at home with one of her owners, silently snoozing all day.

Then, Penny started stealing items of Zelda’s clothing. She’s always had a fondness for my dirty laundry, so it was cute to watch her suddenly make off with little socks and bibs, a little hat patiently hidden under our pillows. We started to see her creep off into corners, digging imaginary holes, burying her treasures nervously. Then, a few months ago, things started to go south for old Penny. Zelda started sitting up and reaching for Penny’s tail. Penny didn’t like this development, and she didn’t hide her feelings well. The entire family — all four of us — were sitting on the floor of Zelda’s room the first time Penny sort of snapped at her. Zelda had grabbed the fur on her back and, before one of us could stop her, she tugged. Penny has snapped at us before, usually while in bed, but in her nearly eight years of life, she has never managed anything resembling a bite. Her “snap” is more of a warning, delivered with her mouth, rather than an intention to harm.

The baby doesn’t walk yet, but she’s working on it, and Penny knows it, so the relationship has deteriorated progressively, on Penny’s end, to this: A few mornings ago, I walked downstairs to the living room, where Penny was asleep. Zelda was in my arms, and laughed when she spied the dog. Penny perked up, unsure for a split second, then emitted a low, slow, almost lazy growl. We walked into the kitchen and I set the baby down. The growl continued. It wasn’t a growl that required work, but it was consistent. Zelda was probably twelve feet away from her, and crawling in the opposite direction. But still, Penny needed to do this. To express something. Zelda laughs at the growl, determined, as in all things, to make the joyful best of it.

What is she telling us? Zelda is a threat to her, clearly. She moves quickly and unpredictably these days. She doesn’t understand boundaries. Penny is a nervous mess: big sister doesn’t quite “get” little sister these days. We’ve explored behavioral therapy. We make jokes about sending her to live with my father. But we’d never do that, and I believe that the situation is temporary. Long term, I know, they will learn to love and appreciate one another, as we love and appreciate both of them, despite their annoying little habits. Until then, we have decided that Penny might benefit a bit from a Prozac prescription. Our veterinarian assures me that this will make life more enjoyable for her and for us.

Because if Penny isn’t exactly quite as important to us as Zelda is, she is still, bad ‘tude included, part of the family. And it is hard to watch her enjoyment of life wane as Zelda’s increases, as she works hard at learning to walk and talk. Penny’s worries have seemingly grown to a point where life feels unbearable to her, and they wear on us, too. Once, years and years ago, a little help from some low-grade antidepressants helped get me out of a rut. My hope is that they’ll do the same for Penny, and that they’ll get her back to where I know she wants to be: snuggling with Zelda like she’s a new toy.

THE PARENT RAP is an endearing new column about the fucked up and cruel world of parenting.

The Triumphant Rise of the Shitpic

by Brian Feldman

In the first chapter of his book, After Photography, digital photography theorist Fred Ritchin explains the central selling point of digital over analog:

Digital is based on an architecture of infinitely repeatable abstractions in which the original and its copy are the same; analog ages and rots, diminishing over generations, changing its sound, its look, its smell. In the analog world the photograph of the photograph is always one generation removed, fuzzier, not the same; the digital copy of the digital photograph is indistinguishable so that “original” loses its meaning.

Put differently, the common perception is that digital files can’t decay. The grooves in a record are eventually worn down by the needle, while an MP3 file retains its data structure. If you open a JPEG today and then again 20 years down the line, the photo will not have changed at all; it won’t have yellowed or faded or have developed frayed edges. This guarantee of digital preservation is why I spent hours scanning family photos at high resolutions and transferring home movies from 8mm magnetic tape onto a hard drive for my parents. When you transmute something into digital, the assumption is that you preserve its fidelity forever.

Ritchin first published After Photography in 1999. Digital photography was becoming more popular, but we hadn’t yet started to put all of our photographs online. Since then, as files are put through a myriad of compression algorithms and Instagram filters, a new aesthetic of digital decay has started to emerge.

Let’s call them Shitpics. Because they look like shit.

Shitpics happen when an image is put through some diabolical combination of uploading, screencapping, filtering, cropping, and reuploading. They are particularly popular on Instagram.

For instance, consider this post by the very famous celebrity Ludacris.

There’s a lot going on here. Let’s try and figure out how this image ended up in its current state.

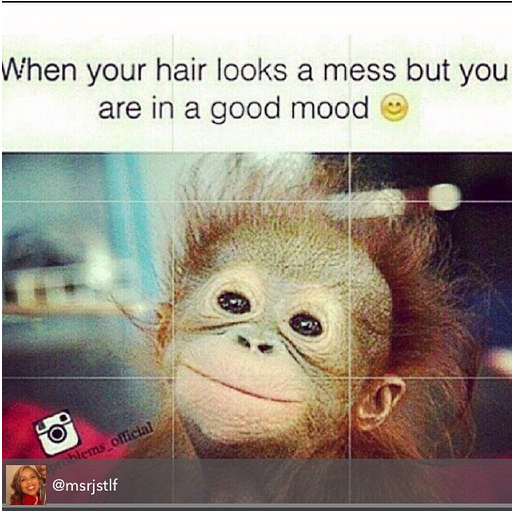

The image was probably created by the joke account @blackgirlproblems_official, where it looked like this:

There are a few clues that this is probably the original. The text is centered and sharper, and the emoji is more than a smudge of dirty yellow gibberish. The picture of the monkey is clear (and cute!!!). All of the text in the watermark is legible.

Then this meme went through hell.

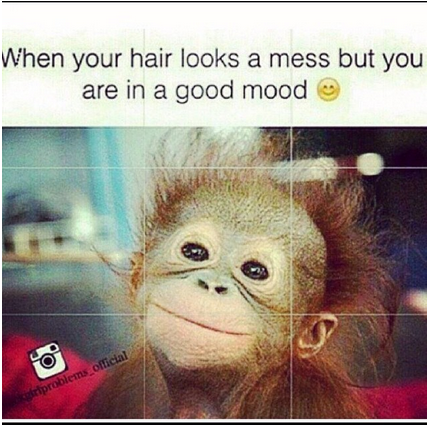

It was saved and cropped numerous times. There are a few signifiers of this: The text is cut off on the left side and there are slight black bars at the top and bottom of the frame. The greenish cloud around the text also indicates an absurd amount of (re)compression.

Maybe the most baffling part of this is the appearance of the rule-of-thirds grid, which likely came from Instagram’s upload screen. Which means that someone screencapped their upload process and then uploaded that? And the grid somehow doesn’t even reach the top and bottom edges.

The version of this image from @msrjstlf indicates that it was probably not run through a filter at any point, since the whitespace seems to have stayed mostly that. The lower left corner of the picture does show, however, just how many times it has been reconfigured: the “black” in “blackgirlproblems_official” has been absorbed by section of blanket that has been widening and darkening as the macro travels through the wringer.

Then Ludacris puts the cherry on top: a translucent gray regram banner crediting the account that he got it from (though not, of course, the original photographer or even macro author).

The Shitpic aesthetic has arisen from two separate though equally influential factors, both of which necessitate screencapping instead of direct downloading. The first is that Instagram, which has no built-in reposting function, doesn’t let users save images directly. This means that the quickest way to save an image on a phone is to screencap it, technically creating a new image.

The second, more important shift is the new macro format that divorces text from image. Classic memes (jfc “classic memes” what are we doing) had text directly on the image, written in Impact font in a particular style — white with a black border. That changed with the rise of the text setup/image punchline format on Tumblr, particularly on the blog What Should We Call Me, which spawned and continues to spawn imitators. Twitter began to imitate this when it changed tweet formatting to hide image URLs (pic.twitter.com) from tweets, easing the transition from text to image, from setup to punchline.

It’s difficult to send someone a technically exact copy of these types of jokes, because they can’t be bundled into a single file such an image. Sending the URL where the joke is hosted requires someone to load an entire webpage, which is relatively laborious on mobile, and so they necessitate being screencapped.

In general, directly saving images on mobile is a function that, even when available, most people don’t bother to use or even learn (saving files locally — in any kind of file system — is generally discouraged in smartphone operating systems). Screencapping is just easier — it’s the quickest way to get something from the internet to your camera roll. That’s why even classic-format memes have fallen victim to the Shitpic process.

People have an excuse for everything #gymratprobs pic.twitter.com/2mjnYBNvz5

— Gym Rat Problems (@Gymratprobs) November 15, 2014

When you pair the format’s inherent need to be screencapped in order to attain virality with Instagram’s prevention of downloading images, you get an endless cycle of screencapping and compression through uploading. Throw in the occasional filter, or watermark, or regram tag, and let the process carry itself out for a while, and eventually you get a Shitpic. The layers pile up, burying and distorting the original.

The rise of the Shitpic demonstrates just how little ownership there is on the internet: Shoddy workarounds and subpar image quality are a small sacrifice to make, so long as your version of a joke goes viral instead of someone else’s. That the image is a muddled cacophony of compression artifacts and blurry emoji matters little, so long as your screenname is above it.

Perhaps most importantly, the Shitpic aesthetic could very well be the first non-numeric indicator of viral dissemination. Metrics such as pageviews, impressions, Facebook referrals, YouTube view counts, and BuzzFeed viral lift all attempt to quantify virality in some way. To the layman (and, let’s be frank, some industry experts too) all of this is gibberish.

But if you look at a Shitpic, you can instantly tell the level of virality by how worn it looks, how legible its text is, how many watermarks adorn it. You can count them much like you would rings on a tree. A pristine-looking meme engenders skepticism — “This can’t be that funny, it hasn’t been imperfectly replicated enough.” But when you see that blurry text, partially cut off by the top of the frame, and a heavily compressed picture of Kermit below… that’s when you know:

This is gonna be a good-ass meme.

Bodies Uncounted

There are perhaps other weeks of the year that the New York Times could have chosen to lay off more than twenty reporters and editors, weeks that are not so deep into the holidays. And yet, why not this week? In the end, is it so different from slow, quiet purge, a few people, one publication, one budget at a time at Conde Nast over the last couple of months? Or the five hundred bodies wordlessly thrown from the building as Time Inc. was tossed off from Time Warner? A certain kind of media reporting — which is to say, much of it that is not about BuzzFeeᴅ or Vice — has become more like writing autopsy reports, grim and technical and inevitable. Through that lens, it’s little wonder that the Times’ media desk suffered the most; it could not be any other way, even at a time when it feels like so much loss is left unreckoned.

Garbage Garbage

“2014 was simply a trashpile of world events and sewer people. The slop started piling up at the start and never slowed down.”

New York City, December 15, 2014

★★★★ Morning sun entered the apartment from the west, off a high window across the way. A spider, glowing amber, marched up the sunny wall. Passersby on Broadway had blinding auras; light sparkled in the now-bare twigs in the crowns of the oaks looming beside Prince Street. Shadows rounded each pebble in the coarser sidewalk pavement, and traced the swirling grain of the finer concrete. While it all lasted — till the sun went down in a wash of orange and magenta — it was as lovely and painless as December could plausibly hope to be.