New York City , December 18, 2014

★★★ Individual buildings stood out golden in the first rays of dawn, arriving so late that the day had seemed overcast. Colors ripened, the sunrise no longer a secret reserved for early risers. Wind tossed the colorless dry leaves around in the forecourt. Blue construction mesh lit up along the edge of a new luxury tower in the distance. The sky was full of light that couldn’t reach into the streets yet. Then the sun found its way in, casting long midday shadows. A pennant of caution tape tied to a traffic cone fluttered in the same direction. Short as they are, though, the days remained perversely changeable; before the afternoon was done, the sun had vanished into a gray pre-dusk, which showed the lights in the windows to their advantage as it deepened on a crosstown walk: Here warm illumination on a wooden domestic stairway, there the cold yellow of office fixtures. The cold was deepening, too, and by Seventh Avenue the wind was something to be braced against. Eyes burned coming in out of it.

Boo Crime

The first season of Serial is over, and the reverberations from the world’s most infuriating podcast have only begun. It’s clear, however, that its outrageous success will yield at least two direct results over the next year: A few more advertising dollars plugged into potentially buzzy podcasts, and an explosion of the “true crime” genre across media. There are so many crimes, after all.

But the forthcoming flood of true crime stories — and the many other forms of crude Serial imitation we’re about to be inundated by! — from new and unlikely sources should be largely, if not exclusively, understood by the forces that produced them: a desire to capture some of Serial’s success, or at least its audience, paired with little intrinsic understanding of what actually made Serial a hit, or even genuine interest in true crime as a genre. We’ve witnessed a similar phenomenon over the last two years in the so-called longform boom (not coincidentally, much of this true crime ooze will be rendered in forms that are probably very long and, nearly as probably, serialized). Look, for instance, at the lushly rendered long things at one of the web’s premiere chum factories, The Weather Channel Dot Com, which exist not because of TWC’s deep commitment to storytelling, but to provide a sliver of a halo for a site whose most valuable front-page real estate is given over to stories like “You’ll Never Guess What Caused JFK Jr.’s Deadly Crash.”

As Serial should have made starkly clear, true crime stories are difficult to report rigorously, nearly as hard to write (or record) clearly, and just as arduous to edit conscientiously; true crime stories, at their best, aren’t just riveting but illuminating, uncovering something forgotten or buried. But much — most — of what will emerge directly from Serial’s slick afterbirth will be poorly reported, written, or edited, if not all three. This is true of much of the media produced every day, but the source of a true crime story’s power makes the consequences of screwing it up all the more grave: People, not just readers, will suffer, perhaps terribly, for it. (See, to some extent, the results of Rolling Stone’s intense desire to have a big rape story precisely when it did because it was The Right Moment for one — and it’s an institution that generally knows what’s it’s doing. Imagine what will happen at [redacted] or [redacted] or [redacted] or [redacted] or [redacted] or [redacted] or [redacted] or [redacted].) In the Year of True Crime, every screen is a crime scene.

Bear Stories

by Sam Worley

One afternoon in late August, I sat at a picnic table with a few family members and listened to stories about bears. This was in Upper Michigan, and it was peak season for nature in a region where nature does not require a time of year — blueberries were ripening, toads cooled themselves in the middle of every gravel road. The stories weren’t unsolicited, but the volume of them was a surprise: Over the course of a couple days, I found that everybody from my parents’ generation on up had at least one bear story, and often more.

My uncle recalled a “big bear fight” that appeared in downtown Manistique some decades ago. “It looked like something out of Ringling Brothers Circus,” he said. A bear in a cage was wheeled in and, during the day, passersby could feed it. At night, “they challenged anybody that, if they could wrestle the bear to the ground, they’d give them two hundred bucks or something.” A man named Terry Smith stepped forward. My dad picked up the thread: “Terry Smith was like, what, six-four, big, blond Swedish guy. Toughest guy in town — really the nicest guy in town too — he couldn’t even touch that bear.” I asked if the bear had been declawed; they thought it might have been. “I don’t know if the bear knew all the wrestling rules,” my uncle said.

In 1985, Ian Frazier published a piece in the New Yorker called “Bear News,” in which he suggested that the survival of the grizzlies depended on their ability to enliven our imaginations:

If enough people could imagine a world without grizzlies, and with equanimity dismiss the bears from their thoughts forever, then the bears’ actual disappearance from the physical world would probably follow soon after. I like reading newspaper stories about bears because nowadays the newspaper is such a vital part of their range. There, and in magazines and on television, too, bears fatten on certain feelings people have for wilderness, and suffer for others. They seem to try so hard to remain living things in the midst of all the fantasies people have about them.”

In Upper Michigan, the news is more modest. Grizzlies are large and dangerous; native black bears, by contrast, wander amiably through local lore. Later that night, we ate down the road at the Big Spring Inn, where a bearskin rug hangs over the bar and where black bears once lived in cages out back. Patrons bought soda bottles from a vending machine and fed their contents to the animals — either the original soda or some kind of home-made syrup. Nobody could remember.

People also watched bears at the town dump, where they dined on garbage. The civic enthusiasm that attached to dump bears — a bona fide cultural event in various parts of the country — strikes me as the charming evidence of a more innocent age, like smoking in restaurants. Until the mid-twentieth century, dump bears were a sanctioned attraction at Yellowstone, which disposed of its garbage on-site. Visitors gathered nightly for “bear shows,” sitting, according to a National Park Service history, on wooden bleachers constructed for the purpose: “An occasional park ranger, mounted on a brave horse, would often ride into view and give an educational talk about bears, while in the background, both black and grizzly bears fought over a particularly choice piece of bacon rind.” The population of grizzlies supping at the Yellowstone dumps grew from forty in 1920 to more than two hundred and fifty bears a decade later.

In 1976, the Resource Conservation and Recovery Act banned the open disposal of solid waste — new landfills were to be lined to protect groundwater, and fresh trash was to be covered promptly with soil, making the whole deal less hospitable to bears. Over the ensuing decades, many existing municipal dumps were forced to close. In the Adirondacks town of Long Lake, New York, where dump bears were central to tourism, the planned closure of the dump in 1991 spurred a number of schemes to keep the bears from leaving the site, including “having everybody separate out their edible garbage and deposit it in special feeding troughs,” according to the New York Times, which conceded that “even in the middle of a dump, there is something undeniably majestic about watching the hulking bears prowl amid the hills at dusk.”

But garbage remains. Bears are not picky about where they get it. In recent years, biologists have noticed the animals getting closer and closer to where people live — the result of climate change and drought, which sends them toward inhabited areas in search of meals from campground trash and restaurant dumpsters. In northern Minnesota, a biologist named Lynn Rogers has been running a decades-long experiment in which he’s befriended, hand-fed, and monitored the behavior of a community of bears. Rogers is a proponent of “diversionary feeding”: basically, solving the problem of bears getting into campground garbage by setting out a buffet for them elsewhere. Rogers is an outlier, and his ideas are generally disdained by wildlife managers, who worry about the animals becoming too comfortable around humans, human food, and human smells. They argue that diversionary feeding might encourage bears to take the presence of a driveway trash can as an invitation into the house, for instance, and that it puts bears at greater risk of accidents like getting hit by cars. This is referred to as “nuisance” behavior in animals, though it seems unfair to fault them.

Rogers’s license to track bears by radio collar was revoked this year by the Minnesota DNR following local complaints that the bears had become, finally, a nuisance. The interspecies clashes he studies, though, will only increase as we encroach simultaneously into each other’s habitats, and the old proximities continue to dissolve. Since the closing of the dumps, not many places remain for the sorts of casual contact that used to characterize — in some small, remote parts of the country, anyway — human-bear relations.

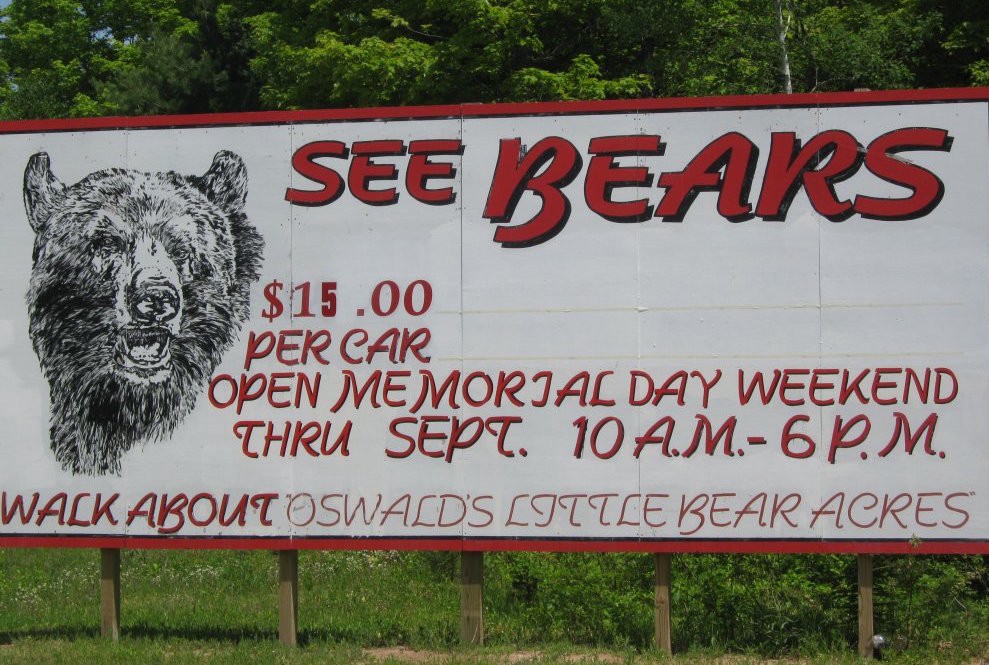

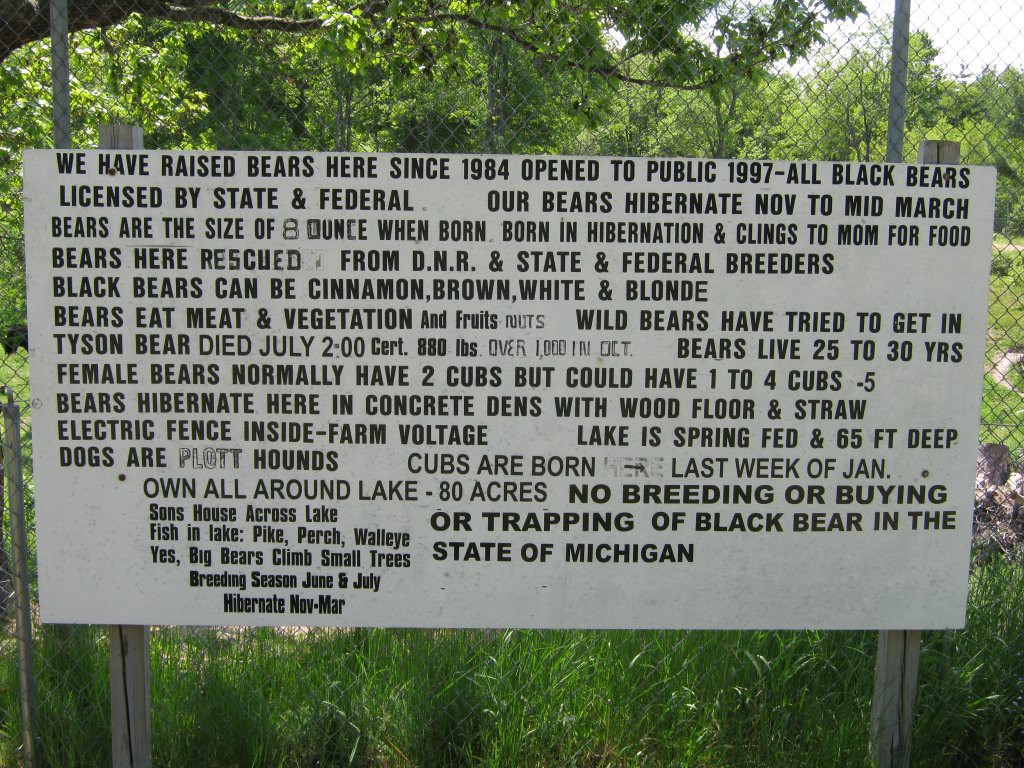

“The spirit of the bear was transformed into human flesh in the Fall of 1939 when Dean Oswald was born in a little riverside town that burned sugar beets grown in the rich, black soil of the Great Lakes,” begins the biography of Dean Oswald, the founder and proprietor of Oswald’s Bear Ranch, the self-proclaimed largest bear-only reserve in the United States, which sits within a patchwork of state forest toward the eastern end of the Upper Peninsula of Michigan. In the human flesh, Oswald — who’s tall and grizzled, with a vaguely bear-like face — doesn’t say much. A retired firefighter who oversees his ursine empire from a patio chair in front of his house, which is surrounded by the bear paddocks, he talks in clipped sentences, mostly in terms of vague operational logistics. Asked what kind of traffic he gets, he said, “Oh, quite a bit,” and then added, by way of elaboration, “Lots.”

Oswald’s ranch is currently home to twenty-nine bears, most of whom are rescue animals — cubs whose mothers were hit by a car or killed in a logging accident, or abandoned by “people having them that just ain’t supposed to have them.” Oswald said that bears are like puppies, or children (“You got one, then you get two, three, and four”). He has favorites, but he’s not so effusive as to describe them in detail. They wander within four capacious habitats, segregated by age and sex, across two hundred and forty wooded, fenced-in acres.

On the sunny day in August that I visited, the bears clustered near the edge of the fence, lying around or pacing back and forth. Tourists watched and threw apple slices, which were available for purchase. A couple bears started fighting, which Oswald told me was normal; it was how Tyson, the ranch’s most famous resident, who was thought to have weighed a thousand pounds, died. “Like Andre the Giant was to the human race, Tyson was to the bears,” Oswald said. Tyson won the fight, but died of a heart attack afterward.

Oswald lived in lower Michigan until his retirement in the mid-eighties, when he moved north to fulfill what his biography calls his “lifelong dream” of owning a bear. At the same time, with bear-friendly dumps closing across the country, the dynamics of bear spectatorship were shifting. Word of Oswald’s ranch got around, and by the time he had five bears, Oswald said, people were bringing their families to see them: “I thought, well, it’d be a good idea then to put a gate up. Let ’em pay for the food.” Today, Oswald feeds the bears every day at 4:30 PM with whatever is on hand, including scraps from local restaurants and supermarkets (or, in the case of cubs, from a bottle). “And bad little boys and bad little girls,” he added, theatrically growling that last word.

In 2012, Oswald ran into trouble. The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service discovered an old state law, the Large Carnivore Act, which prohibited contact between humans and, among other creatures, Oswald’s cubs — a major attraction at the ranch, where visitors were able to feed them Froot Loops by hand. “All of a sudden, they said, ‘Well, whose life can we mess up today?’” Oswald told me. The situation drew a little media coverage — the Detroit Free Press noted that the trouble was initiated by a complaint from “an attorney in town from the East Coast.” Organizations that weighed in, including animal rights groups and the Detroit Zoo, raised concerns over the effects that the contact has on both the bears and the visitors — objections that seem like an old unease, transmuted into a new one, about the boundaries of our relationships with wild animals as contact between people and bears has become less intimate and more formalized. Oswald and his antagonists reflect an adaptation: to wiser wildlife-management practices, to the physical realities that harm or displace bears, and to market forces that transmute animals into attractions. We closed the dumps; they headed for the dumpsters and we drove to the zoos.

Last year, with the help of a state senator, Oswald got the law changed, so that direct contact is now permissible between humans and bears when cubs are younger than nine month of age or weigh under ninety pounds — but now they’re fed Froot Loops with a spoon.

Photos by Julie Falk and Andrew (1, 2, 3)

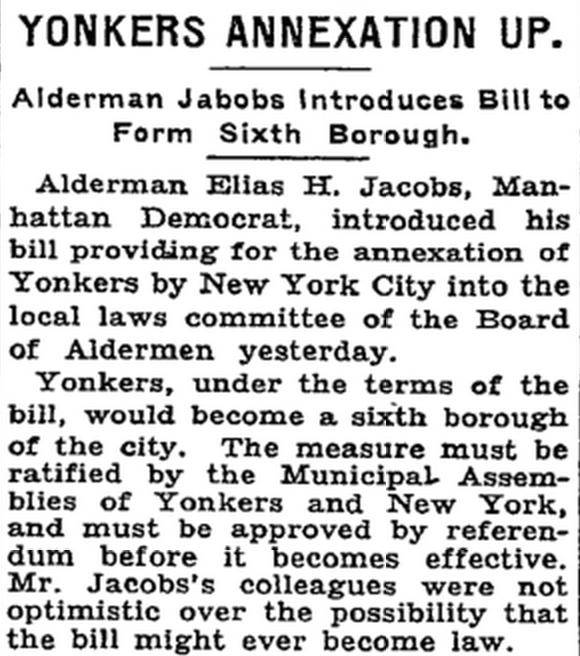

The 32 Sixth Boroughs of New York City, According to the 'Times,' in Order from Worst to Best

• Newburgh (May 11, 2010)

• Rikers Island (November 21, 2012; May 8, 2005)

• The Palisades (December 28, 1980)

• Scarsdale (April 14, 1991)

• Hoboken (August 8, 1999)

• Jersey City (November 22, 2014; November 21, 2004; September 14, 2003; October 31, 1985; April 15, 1984)

• “Boca and surrounding Palm Beach County” (December 10, 2004)

• Yonkers (May 5, 1927; November 3, 1934; April 16, 1911)

• “New Jersey’s gold coast, stretching from Jersey City to Weehawken” (July 9, 2014)

• South Florida (December 16, 2005)

• Jersey City (May 15, 2008)

• New Jersey (May 10, 2013; August 7, 1988)

• Fort Lee (September 7, 2012; April 8, 1979; June 1, 1973)

• Philadelphia (November 24, 2014; December 15, 2013, July 31, 2013; July 29, 2012; December 1, 2009; October 1, 2009; August 14, 2005, et al)

• Southern Westchester (May 08, 1977)

• Nassau County (June 17, 2009)

• Montclair (August 19, 2007)

• Bergen County (March 21, 1976)

• Miami (December 19, 2014; July 31, 2012; February 2, 2007; May 16, 2004; March 7, 2004; April 23, 1973, et al )

• Nashville (September 3, 2014)

• Louisville (March 12, 2009)

• Harlem (June 5, 2012)

• The Rockaways (August 23, 2004)

• Los Angeles (September 3, 2006)

• Beverly Hills (August 16, 2000)

• Fresh Kills (October 10, 1999)

• Puerto Rico (February 28, 2005; May 11, 1980)

• Hudson County (October 29, 2006)

• “water” (July 20, 2012)

• “waterways” (February 20, 2011)

• Washington Heights (March 4, 2007; August 20, 1989)

• “Thugdom” (November 20, 2004)

2014, In Order

12. December

11. November

10. October

9. April

8. March

7. February

6. January

5. September

4. August

3. July

2. June

1. May

Related: 2013, In Order

Gift Available

“’I’m saying to myself, Jesus, they’re not going to do it if they don’t get preferential treatment,’ Johnson said. ‘So we decided to step up and do it ourselves.’ Melville House will publish the [Torture Report] in paperback and e-book editions on December 30th. Copies will go for $16.95, available everywhere books are sold.”

51 Minutes in a Revolving Door

by Jess Lowry

Mid-turn, and the whole thing stopped moving. With a sighhhhh. And a click. The person in front of me (hair scraped into a bun and brown coat) was able to squeeze out. As was the person behind me (heavy boots and red scarf). But I was trapped. By three walls of glass. After much pushing and shrugging on my part, the security guard approached holding up a note written on the back of a ticket stub. Are you ok? Door stuck? His name tag said “Bill” and he could not have been older than 19. “I can hear you,” I said. “Yes it is. And yes, I’m fine.” Good, Bill wrote on his hand before, subsequently, transforming these words into a thumbs up. He turned to another security guard: “I think the door’s stuck,” he said. Bill’s Friend looks at the door. And then at me: “Christ.”

10:15 AM: Bill and his Friend start to pull the door. And like any self-respecting young woman living in a post-Liam-Neeson-Taken era, I decided to call… my father. “Dad. I’m trapped in a revolving door.” There followed a crunch of cornflakes. “Is this a metaphor?” My father asked. “Did you want to speak to your mother? You know I’m no good at these sorts of problems.” I tell him it’s real. I tell him it’s happening. I tell him to feed my fish if I don’t make it out. “Honey, [cornflake crunch/ swallow] have you actually tried pushing the door. Push the door. See what happens.” This whole time, museum patrons are trying to use the revolving door/my new glass prison. Puzzled when nothing happens, they look at me. And then exit through the side door to the left. Some of them shake their heads or roll their eyes. I have, they presume, broken the door. Children are crying: they wanted to go through “the spinning” door: “What did the lady do?” A small girl asks her mother. “I can hear you,” I say.

10:20 AM: After five minutes of unsuccessful pushing and pulling, Bill’s Friend approaches the glass with a note: Facilities are coming. I nod: “Good stuff.” Bill’s friend raises his eyebrows, blinks and writes back: How’s your air? Asthma? Oh. Right. Ok. Right. Because *could I* suffocate in here? I shake my head. He smiles and writes: Ok. Stay Calm. Stay still. “I”ll try,” I say as he walks away. So, like they tell you in those high-socked Primary School fire drills, I sat down. In order to avoid the non-existent smoke. All the air is at the bottom of the revolving door, right? Right. Ok. Good. Knees to chin.

10:27 AM: Bill, Bill’s Friend and the newly arrived Facilities Man and Woman all stand in a line and give multiple thumbs up. “She has interesting hair,” Facilities Woman whispers, cocking her head to the side. “I can hear you,” I reply. They nod with big grins: “Keep — smiling,” Facilities Man says through gritted teeth: “Keep — smiling. Keep — her — calm.” After exuberant waves and hammer mimes, the latter two start working on the mechanism to the side of the door. Meanwhile, Bill and his Friend get back on their walkie-talkies: “We have a situation here.”

10:32 AM: All this time, out on the street, people wander past. Students, Christmas shoppers, university staff, museum staff, old, young, prammed, wheel-chaired: they’re all moving. There’s scuffing and shuffling and running for the bus. Loitering and lolling and a man grabs a woman’s hand. They’ve been walking in stride but she yanks her palm away, and places it over her neck, saying something I can’t hear and backing away. A mother leans down to tie a girl’s yellow shoe. A man drops a binder and the papers scuttle over the pavement like one-winged doves: hovering and falling and taken by cars.

Alerted by the group of small people around the door, some of these pedestrians smile in my direction. Or stop to stare. “Art installation,” one woman sighs to her companion: “total student rubbish.”

10:33 AM: Cue the arrival of a group of my scarfed students from last term. They wave. “Hi Jess!” Facilities Woman shakes her head and looks up from her position on the pavement: “she can’t hear you.” The students nod in unison and grin. Two of them salute and they all keep walking, arm-in-arm. This predicament, it seems, does not look unusual to them.

However, their class was Fiction Writing 101. And — among other things — I made them follow strangers around supermarkets, write about the contents of their shopping trollies and wear each other’s shoes for a day: their reaction here is fair.

10:39 PM: Cue the appearance of French Neighbor. Giselle is beautiful and French and may have been lead to the impression that I, in fact, speak French. “Allo? Jezzie?” She gets right up to the glass and says something to Bill’s Friend. He replies in French and is, with wide eyes, clearly transfixed. She is beautiful and French and the Facilities Man stops working for a second to look at her face. (Leave Giselle! You are too beautiful!). She puts her un-opened bottle of water in front of the door and nods at me. Then — borrowing the pen from Bill’s Friend who is ignoring the (now audible) yelling on his walkie-talkie — she writes a note and presses it against the window. I do not, as it happens, speak or read French. But this all feels too complicated, at this point, to explain through a stuck revolving door. So I nod: “Oui.” She kisses her fingertips and places them on the glass, mimes washing her face and points to the bottle of water. “Au revoir,” she says though, very loudly though so its more like: “OHHHEVVWARRRRRRR.” And she’s gone. Bill’s Friend looks bereft, and watches her turn the corner: a whip of (so gold it’s almost) silver hair around red brick.

10: 45 AM: Cue, of course OF COURSE BECAUSE WHY NOT, my Supervisor and her Colleague. They have nice satchels. And the highest heels. White necks above long, black coats. Small earrings that catch the light. They’ve come from a lecture and are, loudly, discussing the “Poor quality of the speaker.” Supervisor stops mid-step and looks at me. Sitting. In a revolving door. Wearing a strange jumper. Holding a book. That she gave me to read… three months ago. There is no surprise in her voice, rather resignation when she turns to her high-chinned Colleague: “That’s Jess. Over there. In the door.” Colleague nods, knowingly: “Ahhhh.” She accompanies this with an exaggerated sad face at me. “I can hear you,” I say, pointing at my ears.

10:47 AM: With her leather folder under her arm, Supervisor talks to the small crowd working on the door. “How long?” And, “How much?” And, “Who?” And, “What?” And, “Ridiculous.” Her voice, eve outside the office, is sharp and bright. Thin like a knife. Bill’s Friend stammers his replies. He wants Giselle back. I know how he feels. Reaching out with her black, gloved fingers, Supervisor approaches a Suited Man who’s just arrived, clutching blueprints. She takes his elbow and leans in to speak. “she can’t hear you,” Suited Man says, hastily turning the blueprints round and round like a steering wheel. Supervisor asks to borrow his pen and her Colleague’s lecture program. She gets right up close to the door though, she does not bend down so that I should stand to read her note: Ok? My usual interaction with Supervisor’s handwriting involves phrases such as (but not limited to): WHAT? or WHY? or NO or GRAMMAR IS IMPORTANT TO THE REST OF US. I nod. Thumbs up. Supervisor hands the pen back to the Suited Man who is squinting at a folder. “Email me,” Supervisor mouths, typing on an invisible keyboard then, raising her free arm into a shrug: “CHAP-TER? SOME-TIME? SOON?” And she’s gone.

10:50 AM: A tourist takes a photo. I smile?

10:55 AM: A group of tourists pose for a photo. I do not smile. I feel like a panda.

11:00 AM: A — very very very small — boy comes up and puts his hand on the glass. Pink starfish. I resist the urge to put my hand up too. It’s busier now and more people are pointing and talking. This exact situation comprises 34% of my nightmares (add laughter, and we’d be at 50%). It’s warm in the glass with the sun coming in. It’s warm and I take off my coat. It’s warm and the noises are loud. And then, I’m holding my own hand. At this point, I start to lose it. Stuck in the revolving door, this is where I’m going to die. Of course it is, though. Fueled by indecisiveness. Wholly transparent. Locked in frustrated, circular motion. Tights-that-I-thought-were-black-but-that-are-navy. Everything within reach. But nothing attainable. Thin air (?). On my knees. With my laptop. And lots of chewing gum. Goodbye world. I call my father again. “Now honey, are you sure you’ve pushed the door?”

11:05 AM: The Museum Director, I know this because he presses his business card against the glass, is there along with more security guards and what looks like a fireman. At this point, Bill reappears. He gets down on his knees and sits at my eye level: We’re going to break the glass, he flips over his piece of paper with a second message: Cover — your — eyes — with — your — coat. “WHAT!” I say as he motions to the fireman who, only now do I see, is holding an axe. A giant axe. Meanwhile, behind me, two (very large) Cafeteria Staff have been pushing against the frame with their shoulders and — both slowly and suddenly — the hydraulics (extremely asthmatic hydraulics) sigh. And something clicks. The glass moves.

11:06 AM: A few of the people watching jump in to help the Facilities Man/the Facilities Woman/Bill/Bill’s Friend/the Suited Man/the axe-wilding Fireman and the Museum Director pull the door from the other side. Wide enough gap. Laptop through first. Then a knee, then a shoulder, then a head. A cheer from the crowd. The air is cold. And the sun not so hot. But my coat is still trapped. Shrugged down in a corner, abandoned like shed skin.

11:10 AM: Sitting on the pavement, Museum Director is asking “how” I would “rate” the museum’s response to the situation. On a scale of 1–10. Are there improvements the museum could make in the future? Are there adjustments they could make in the coming days? “I felt like a panda,” was all I could say.

FEEL FREE TO VISIT THE MUSEUM ANYTIME ON US,

my gift card says,

OPEN ACCESS FOR THE YEAR.

Photo by Zrendavir.

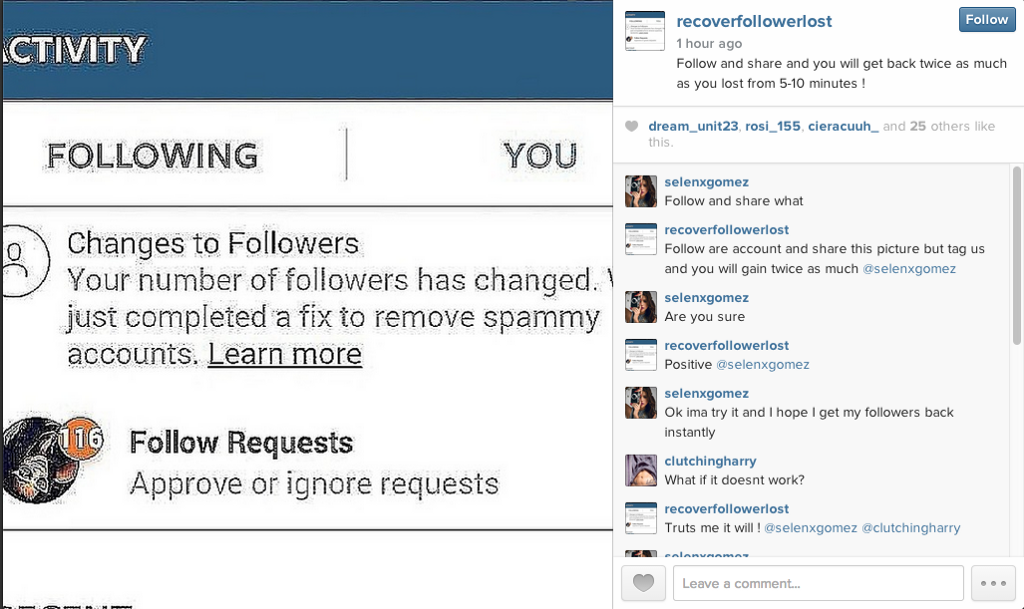

Illusions Shuffled

Business Insider, December 10th:

Instagram has announced that it has officially reached 300 million active users, making it larger than Twitter.

Business Insider, December 16th:

Data provided to Business Insider from social media analytics company Socialbakers shows Instagram is not only gaining traction in sheer numbers of users, but posts from the biggest brands on the photo app are receiving almost 50 times more engagement (at the highest level) too. More users and more engagement? It’s easy to guess which medium advertisers will prefer.

Business Insider, December 18th:

As Instagram’s crackdown on spam begins, distraught users have been begging the company to stop eliminating accounts.

Meanwhile, celebrity accounts have taken the biggest hit.

Popular Instagrammers like Kendall and Kylie Jenner have lost hundreds of thousands of followers, and many celebs have lost millions.

Business Insider, December 19th:

Instagram is a $35 billion business, according to Citi analyst Mark May.

Mark Zuckerberg gained wide attention for paying what now seems to be a paltry sum of $1 billion for the service back in April 2012.

You ask:

What is a user,

and engagement, too?

And how do these concepts relate

to the concept of money?

The answers you seek,

are just out of sight

A little further up

and to the right