New York City, December 21, 2014

★★ The nadir of daylight, and a bleak daylight withal. The children were stir-crazy and full of recriminations. The three-year-old’s foot, stuck under the back of a shirt, was icy; leftovers hot from the pan swiftly grew cold again. Constant helicopter traffic went back and forth against the gray. Past the grove of Christmas trees was a patch of potted orchids, bearing up in the chill. Some people were still bareheaded. Blood oozed from the cold-split thumb.

Good Things of 2014, a Complete List

by Laura Olin

Can 2015 possibly surpass it?

We’ll just have to wait and see.

Never Better, a collection of essays from writers we love, is The Awl’s goodbye to 2014.

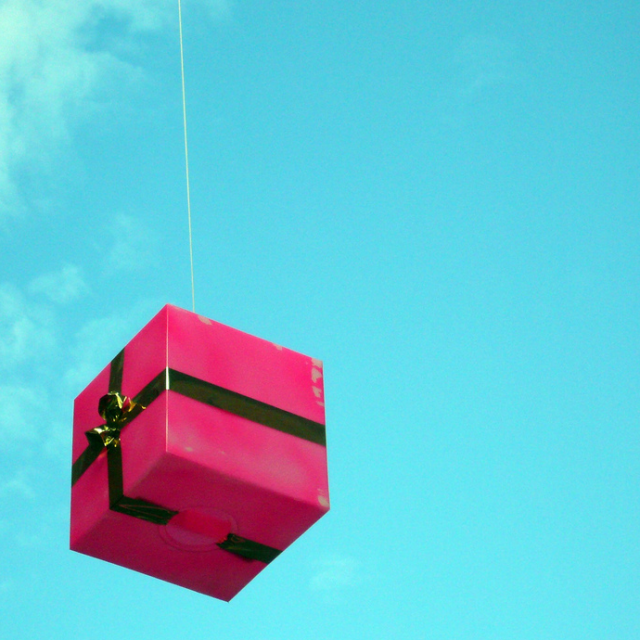

The Best Gift I Ever Gave

by Mallika Rao

Presented by by Capital One®.

During the holidays, we’re often asked what we wish for ourselves. This holiday season, Capital One is instead asking people to share their wish for others. Read on for a touching story that demonstrates the true meaning of giving.

There are no guarantees in gift giving. I learned this the hard way, when I gave my dad a new sugar bowl.

The original, shaped like an overturned onion bulb — round body, pinched base — meant something. My dad had bought it in the seventies, with my mom. Three decades later, the lid was gone and so was she, taken by cancer a month after my 23rd birthday.

In the haze that followed, I’d made more decisions than the one to protect our sugar from bugs: to love people while they’re still here; to conquer vanity, because who knows whether you’ll die with all your hair; and most concretely, to organize the house, so my dear dad could live his life.

The latter task was harder than it sounds. Loss gives meaning to every part of a home — even my mom’s mess of beauty products suddenly seemed precious. My anxieties centralized on a target: replacing the lidless sugar bowl. It seemed to me that I needed the same bowl as the one my parents bought. If I could find an exact double, could everything we’d lost reassemble somehow?

The implications of succeeding thrilled me.

An inspired combination of Google search terms later, I found myself staring at it. Few sights have made me feel that anything can be achieved by faith alone so much as the bowl of my childhood memories rendered perfectly on the screen of our Macbook. When my dad came home a few days later, it was to my little miracle on the counter. Same onion shape, only better.

Of course, nothing could be the same. My dad looked panicked. Where, he wanted to know, was our old, lidless sugar bowl?

I produced the original from the cupboard where I’d stowed it for posterity’s sake. This was not how I’d imagined my triumphant reveal. I felt foolish. I’d tried to fill a crater-sized hole with a sugar bowl. Should I return it? My dad considered this for a moment, then smiled. He put the new lid on the old bowl. Suddenly it was a perfect gift.

To celebrate that spirit of giving, Capital One is looking to hear about your wishes for others. Share your wish for someone else — a family member, a friend, a neighbor, or community — with #WishForOthers on Twitter, Instagram, or the Capital One Facebook page from Nov. 24 through Dec. 23 for a chance to make it come true.No purchase necessary.

Check out this video and then visit WishForOthers.com for more information, official rules, and to see the wishes that other people have submitted so far.

Photo: Procsilas Moscas

Sponsored posts are purely editorial content that we are pleased to have presented by a participating sponsor, in this case Capital One. The views in this article are solely those of the author, not our sponsor.

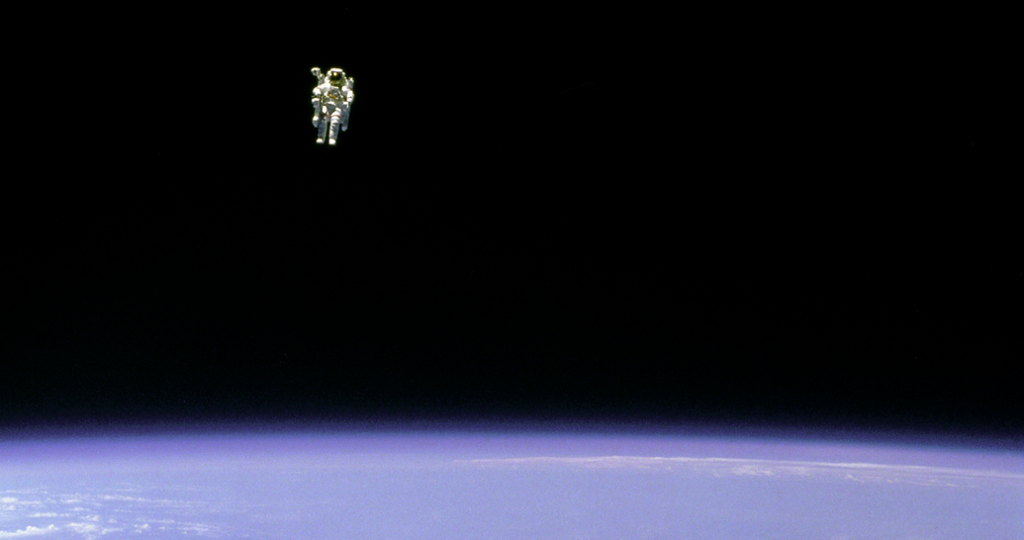

No Things

The year 2014 was, for me, never better than for a brief hour on the morning of Sunday, June eighth, several thousand feet in the air above the southwestern edge of Costa Rica. It was my last day of vacation — my travel day, really. Six of us had spent a week snailing our way around the tiny country in a Toyota 4-Runner. We scrambled first up into the mountains, among coffee plants and volcanoes, and then we wound our way down to the beaches along the Osa Peninsula, flinging ourselves into the merciless surf, for shits and scrapes.

My long trip back to New York had begun around seven that morning. Two friends drove me forty minutes down the gulf side of the peninsula to the lone airstrip in Puerto Jiménez, where I climbed into a Cessna Grand Caravan 208 just after nine a.m. The plane was a twelve-seater with two pilots (a “puddle jumper,” as my father says), and there were six other passengers on board. After about fifteen minutes we made a “technical stop” on the Pacific Ocean side, in Drake Bay, a fact I had been warned about in an email update from Sansa Airlines. What I did not expect was for all the other passengers to disembark. Where the hell were these people going? I could have sworn the stop was just technical. I wondered, was I supposed to get off too?

I stayed put, figuring someone would shoo me off if needed. One pilot secured the door and the other prepared for takeoff. Somehow, I had just won the air travelers’ lottery — I was the only passenger left on the plane. The pilots seemed unfazed by this happy miracle. They spoke to each other through the on-board communication system, which I had no access to. I felt something akin to the exhilaration of being in a car alone for the first time at the age of sixteen, newly licensed, except in this case I wasn’t steering. And then — away we went! I had no reason to believe we weren’t on our way to the San José International Airport, and yet I couldn’t quite be sure.

My own private plane! A laugh bubbled up from my diaphragm, but I couldn’t hear it over the hum of the engine and propeller. I felt invisible. There was no one else I had to monitor for potential signs of airsickness but myself. There had been no safety regulations to review, no exits to locate; the pilots and I needed nothing from each other. They flipped their switches and checked their gauges and ignored me completely. It occurred to me they would have gone through these exact motions whether or not I had been there.

I had achieved a momentary escape velocity, some sort of blissful Lloyd Dobler fantasy — I had nothing to read, no schedule to mind, nothing to say, and no one to tell. I don’t even remember having any specific, language-based thoughts beyond understanding how private air travel could be height of luxury. It was the best feeling I had all year, and I think it only lasted about forty-five minutes.

I didn’t get home to my apartment in Manhattan until well after one in the morning, after two more flights and a five-and-a-half hour layover in the Orlando Airport. I have no recollection of what I did with myself for three of those hours, but I do recall watching the San Antonio Spurs lose by two points to the Miami Heat in Game 2 of the NBA Finals — it was an exciting game. The rest of 2014 was pretty crappy. I hurt people I loved, I fought with a landlord, I got a canker sore ON MY TONSIL. But for a brief moment there in the sky, things were good, because there were no things.

Never Better, a collection of essays from writers we love, is The Awl’s goodbye to 2014.

A Long December

by Bex Schwartz

Fun fact! My frosh year of college, which I am calling frosh year because I went to Wesleyan and that is what we called it, I went to a concert in New Haven. Possibly Hartford. More likely New Haven. We went to go see the Counting Crows. Cake was the opening act. In terms of Cake, this was before they had that hit on MTV, and in terms of the Counting Crows, let me just say that “Anna Begins” made me feel things deep in my heart. If you are younger than me, you probably call this sensation “getting the feels” or “feeling some sort of way.” At the time, I just called it the quickening. That particular song gave me the quickening. And so, in 1997, I was really excited to go see the Counting Crows. #SorryNotSorry but whatever.

And so. Cake was in the news recently. That was a bummer. And then I ran into my friend Trace who went to that very same Counting Crows concert with me. That was nice! And then I was thinking about the Counting Crows a whole lot for the first time in possibly over 15 years because, I mean, it’s been a long December. Right?

“It’s been a long December and there’s reason to believe maybe this year will be better than the last.” — Counting Crows

Adam Duritz’s dad worked in the same medical practice as my other friend’s father and they went to the same high school. So we waited outside the stage door and my friend yelled out the name of the school and Adam Duritz ignored us. Then Sara Gilbert showed up (She was attending Yale at the time? I guess?) and she was on (or hosted?) SNL with the Counting Crows and so they had a nice reunion and eventually we gave up because, admittedly, we weren’t even about to recognize the other Counting Crows if they came outside, so, really, why bother.

But, holy smokes it’s been a long December. The longest December of all. Wake me up when December ends. If this year is truly to be considered never better, then I am worried about the future. I mean, I’m always worried about the future because we’re totally going to run out of oil and then water and then there will be terrible wars and someone will use a nuclear weapon and render the entire planet into a dystopian nightmare worse than anything in those YA books we like so much.

Or not really, in theory, but before I started treating my anxiety that is what I thought about all the time. You know how every 9/11 they do that “tribute in light” thing and blast those mega beams of light into the sky? I used to look at those lights and think about how much electricity it took to power those things and then I’d worry that New York would have a blackout and all terror would break out. And then we had a blackout in the summer of, what was it, 2003? And it wasn’t that terrible — I wasn’t trapped in the subway or in an elevator, I just walked home and kept magically running into friends along the way. And the hospitals had generators and planes didn’t crash and people lit fires in trashcans and drank beer on the sidewalks. And then when we lived in the dark after Hurricane Sandy, it was scary but I was still okay. It wasn’t the end of the world, luckily, for me, although I acknowledge that is a uniquely selfish and narcissistic thing to say. I just spent a lot of time listening to my battery powered radio and checking twitter until my phone ran out of energy and then I’d worry about the Rockaways and Staten Island so then I’d drink a bunch of wine and go to sleep.

I stopped worrying about the blackout issue for a little while but then when it would get really hot and everyone started using their air conditioners at the same time, I would sometimes feel that same fear that we might run out of power. And then I would think about what would happen when we completely run out of oil and then water and then it would always be a blackout. As in: the power would never ever come back on. There would be scary things happening everywhere, all the time. Then I realized it was easier to think about that possibility if you just referred to it as “when the zombies come” and that’s when I got a pickaxe.

If you stay awake late at night thinking about your survivalist options if we run out of power or water or when the zombies come, you might feel a certain way. You could also call that a quickening, but that would be a bad sort of quickening. The bad sort of quickenings went away for me once I acknowledged: I am an anxious person and my reality is not always the most rational. And when you live here, it is really easy to be an anxious person because if you let yourself think about it, there’s a lot to worry about. The tunnels under the river could collapse. The tribute in light could wipe out our power grid and then we’d live in the dark. Your elevator could plummet dozens of stories to the ground. Those new touchable maps in subway stations could be crawling with the next pandemic. Welcome to New York. It’s been waiting for you.

“Welcome to New York. It’s been waiting for you.” — Taylor Swift

Just kidding! That is the worst song on the Taylor Swift album of 2014 which is called 1989! But you know what does not suck? Most of the rest of that Taylor Swift album, other than maybe “This Love” because it feels Maroon-5ish. The rest of the songs are fucking awesome. Once I listened to “Clean” for the entire train ride between Philadelphia and New York. It’s been a long December and there’s reason to believe maybe this year we listened to more Taylor Swift than we possibly thought we would. Taylor Swift’s songs made me feel something. They made me feel like it’s been too long since I’ve gotten the feels. There haven’t been any quickenings in a long time because I let myself turn into a work robot and work robots don’t have emotions. Beep beep boop.

So I realized if I want to feel some sort of way, I have to let myself have emotions again. This epiphany coincided with the fact that everything sort of got all sorts of bad this December. The sort of bad that even a pickaxe can’t prevent. Suddenly, December was just dreadful. And then there I was, thinking about the Counting Crows. Such a long December. The longest of all time.

“But the girl in car in the parking lot says “Man you should try to take a shot

can’t you see my walls are crumbling?” Then she looks up at the building and says she’s thinking of jumping. She says she’s tired of life. She must be tired of something.” –“Round Here”, Counting Crows.

The first time I encountered death, it was when a girl a few years older than I was in high school passed away. My mom and I went to the wake because we lived in a very small town and in very small towns, everyone goes to the wake because you all know each other. It was very, very sad. My mom and I got into the car and “Round Here” by the Counting Crows was on the radio. The song was very good and very intense and my mom and I sat in the car together and cried. I didn’t know the girl very well but I went to her senior prom and she was part of the same group of friends I was with. After the prom, we went to the diner because we lived in New Jersey. I ordered coffee and stirred a Sweet & Low packet into it because I was fifteen and we were all sorts of messed up about fat and calories back then. That girl’s date said, “That will gave you cancer.” His date was very sick. I nodded slowly and kept stirring.

The other week, while the rest of the world was crumbling and there were helicopters overhead every night and everything on the news was more and more impossible to believe, a friend of mine was dying in Brooklyn. She was seven and she was not tired of life at all. She was very strong and very brave and wiser than most of us could ever hope to be. The night she passed away, I came home and listened to that Counting Crows song because I was thinking about the wake I went to with my mom. And I wished I could talk to my mom.

I spent a lot of time in Brooklyn with my friend and her father, who is also my friend. One night we went out for whiskey because that is sometimes a thing you might do when someone you love is very sick. I ran into another friend whom I hadn’t seen in a very long time. She told me that our mutual friend, a friend with whom I was once very close, had passed away several years before. I am a neurotic narcissist and I blamed myself because I was the one who let the friendship dissolve, a very long time ago. And then she died and I didn’t even know. I wanted to talk to my mom about that but she is dead so instead I called my dad and we talked it out and at the end of the conversation my dad said, “I am so happy that you can call me and talk to me about these things.” Because things can change. We can talk about our emotions and not be work robots. Maybe. Slowly. In baby steps. Maybe we can have feelings again.

“It’s been a long December and there’s reason to believe maybe this year will be better than the last.” — Counting Crows

Let’s imagine that Adam Duritz is singing about this particular year. Maybe December 2014 will be better than we remember December 2013. Remember how cold it was last year? And there was so much snow. (I think?) Maybe next year will be even worse and we will remember this December as being the best. Never better.

And yet I am an optimist and I believe it can only get better. Even better. Better than this. I don’t have the solutions to everything that has sucked so hard this December. I’m not entirely sure I have the emotional capacity to process everything. Two women flew here from Singapore so I could marry them because here in New York, everyone is considered equal. Sometimes after midnight I might go out to buy a seltzer, because I feel safe doing so. I feel like a lot of my favorite people are doing things to make themselves happier. Never better? I don’t know. All I know is that I have a pickaxe. And I believe that we can fix things, if we are brave enough to talk about it, even when it makes us anxious. Bring it on, 2015. Bring it the fuck on.

Never Better, a collection of essays from writers we love, is The Awl’s goodbye to 2014.

Never Better

by The Editors

The end of the year is here. For many, it is a time to take stock of the past twelve months and look forward to the future, constructing an emotional architecture to support the weight of the hope that whatever comes next will surely be better than the trash heap that came before it. This is a faulty notion. Next year, we will inevitably only remember how much less worse this year was, because nothing ever gets better, especially, but not exclusively, on the Internet.

So, Never Better. That is the theme for The Awl’s goodbye to 2014. The package has been collected here. It features contributions by Natasha Vargas-Cooper, Jane Hu, Casey Cep, Bijan Stephen, Mary Pilon, Jeb Boniakowski, Haley Mlotek, Laura June, Brendan O’Connor, Michelle Dean, Dan Nosowitz, Carrie Frye, Alice Bolin, Leah Reich, Maria Bustillos, Paul Ford, Mat Honan, Casey Johnston, Laura Olin, Silvia Killingsworth, Bex Schwartz, Maud Newton and Alex Balk.

When You're Tripping on Vyvanse and a Man in a Frog Suit Appears

by Matthew J.X. Malady

People drop things on the Internet and run all the time. So we have to ask. In this edition, PandoDaily East Coast Editor David Holmes tells us more about what it’s like to shoot a music video in Brooklyn in 2014.

A photo posted by David Holmes (@holmesdm) on Dec 12, 2014 at 8:06pm PST

David! So what happened here?

So I was helping my girlfriend, the photographer Alison Brady, with a music video she’s directing for this nice Grizzly Bear-ish rock band called Redfoot. I want to make sure I don’t overstate my role or take undue credit, so when I say “helping,” I mean carrying light-stands, sweeping floors, making coffee, and staying out of the way. Available but invisible — which would a fitting title if I ever write a memoir. Or a relationship self-help book.

But sometime around the fourteenth hour of shooting that day, things started to get weird. Part of the weirdness came from taking Vyvanse, which is basically Super Adderall, and which at that point was wearing off and wearing me down hard. (Though it could have been worse: One member of the crew said he meant to take an Adderall that morning but accidentally popped a morphine pill.) As for me, the euphoric focus that carried me through the morning and afternoon had now mutated into a state of semi-consciousness marked by micro-naps, waking dreams, and a perpetual sense of deja vu as moments began to pile on top of one another, as if time was a broken assembly line.

And that’s when I saw the green man.

As Redfoot’s lead singer Luca Pironti emerged from a bedroom of the Bushwick-loft-turned-video-studio, the last thing I expected to see was a man covered from head to toe in a green-screen-ready jumpsuit. After all, we were shooting a music video made up of subversive psychosexual imagery, not some Peter Jackson fantasy epic.

To make the scene even more surreal, the green man was instructed to make out with one of the models hired for the shoot. It was as if I’d suddenly stumbled upon a film set devoted to hipster hobbit porn.

I don’t usually take “behind-the-scenes” photos on set, mainly because a lot of directors get annoyed by them. But this was such an absurd scene — a man who looked like a sperm on St Patrick’s Day making out with a 1950s housewife — that I was willing to risk pissing off the director, even if it meant sleeping on the couch. (She didn’t care.)

That green suit can’t be comfortable. Did that guy complain about it the whole time?

Luca wore the suit with dignity and honor, totally comfortable with having the outline of his penis on display for everyone to see. I did have one concern, though. Unlike King Kong or Gollum or other green-screened characters, Pironti had no cities to destroy, no rings to spaz out over. Instead he had one job: make out with the model. So as soon as he took her into his arms, I couldn’t help but fear for him. The skintight costume left nothing to the imagination, and I worried that Pironti’s subtle and noble crotch bulge would transform into a neon nightmare for all involved. Not that Pironti gave me any reason to believe he’s a creep or an exhibitionist, but dick science is an unpredictable discipline.

Of course, the use of green screen meant that if he had gotten too excited, the offending member could be replaced in post-production by any number of phallic objects, like a banana or a Flintstones Push-Up Pop. But I’m not sure everyone would have recovered from the awkwardness.

Lesson learned (if any)?

I have to say, I was inspired by Luca’s complete confidence inside the suit. He didn’t feel an ounce of embarrassment — or at least he didn’t show it. He just owned it. And I think the lesson here is, just because you’re in a full-body skintight frog suit, making out with a 1950s housewife in front of a camera in a Bushwick loft at 10 o’clock at night, don’t forget that you’re working with professionals. Act accordingly.

Just one more thing.

I know that when we were in college, ADHD meds could be substituted for sleep, sustaining us for days on end as long as we eventually caught up on rest over the weekend. But now that we’re older, that doesn’t work anymore. Especially if you accidentally take morphine instead of Adderall.

Join the Tell Us More Street Team today! Have you spotted a tweet or some other web thing that you think would make for a perfect Tell Us More column? Get in touch through the Tell Us More tip line.

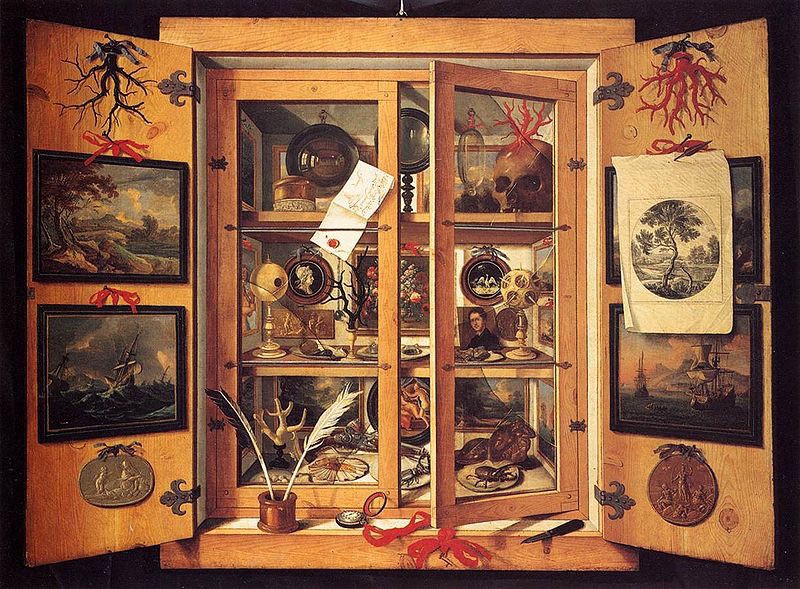

Monsters in the Museum

Monsters in the Museum

by Jacob Mikanowski

Domenico Remps, Cabinet of Curiosities, 1690s

On February 13, 1718, Peter the Great, Tsar of all the Russias, issued an edict on monsters: All monsters, animal or human, were to be requisitioned for the new museum in his new city, St. Petersburg. Peter desired anything in the realm that was marvelous — extraordinary stones, human and animal skeletons, the bones of fish and birds, old inscriptions, ancient coins, hidden artifacts, old and remarkable weapons — but he wanted monsters most of all.

Monsters, Peter believed, were not the work of the devil, but products of nature. He offered generous payment: Delivery of live specimens would fetch a hundred rubles for humans, fifteen for animals, and seven for birds. Dead ones, preserved in spirits, or, failing that, packed in double-distilled wine, were worth ten, five, and three rubles respectively. (A day laborer might expect to earn six rubles in a year). Anyone caught concealing specimens was to be fined and the sum given to the informers.

Peter’s agents fanned out across Russia to fulfill his wishes. In Siberia, pagan hunters were persuaded to turn over their idols; the grave robbers of the Irtysh Valley put down their spades to turn over the Scythian clasps and gold belt buckles they had dug up; and in rural way stations and forest hamlets, emissaries searched for strange births and deformed children.

Peter’s subjects brought him an eight-legged lamb, a three-legged baby, a two-headed baby, a two-headed calf, a baby with eyes under its nose and ears below its neck, Siamese twins joined at the chest, Siamese pigs, a baby with a fish’s tail, two dogs born to a sixty-year-old virgin, and a baby with two heads, four arms and three legs.

Peter’s agents also brought back at least three live children: Stepan, who lacked genitals; Foma, who was born with ectrodactyly; and Iakov, an intersexed blacksmith. They had come far to be put on display in Peter’s museum, but being on view wasn’t all they were expected to do: After hours, they swept and cleaned and kept the fireplace fed. As Russians, they were Peter’s subjects, and subjects were expected to serve.

When Peter took the throne, Russia was unlike the rest of Europe. Science and philosophy, as practiced by Newton and Descartes, were unknown; no one knew Latin; upper class women weren’t allowed to leave the home; and the few foreigners in the country were restricted in their movements and confined to special “Western” quarters of certain towns. Religion reinforced this sense of difference. The Russian Orthodox Church stood as a bulwark against foreign influence from godless Catholics and heathen Protestants — and the church was more progressive than many of its believers, some of whom cut off their fingers or fled into the forest, rather than go along with a change in the liturgy.

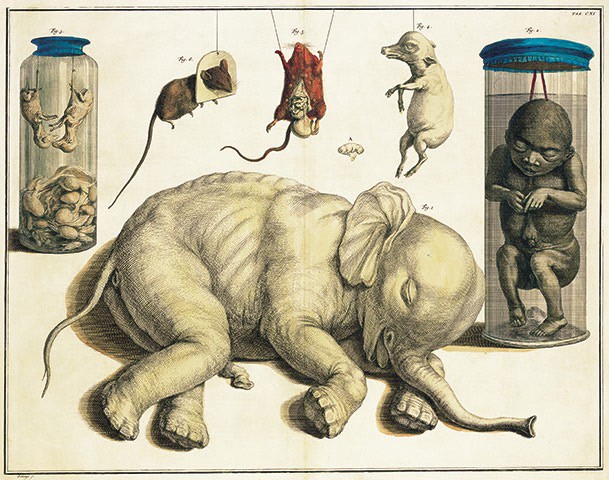

Cabinet of Natural Curiosities, Albertus Seba, 1731

Soon after assuming sole power in 1696, Peter passed a series of laws aimed at bringing Russia closer to the modern, Western fashions he had seen on trips abroad. He reformed the calendar, the army, the way people dressed and even how they ate soup (no more slurping). The museum was part of that ambition. Its exhibits–unusual objects, inventions, and works of art — were designed to inspire his countrymen to broaden their horizons and enlighten their minds. Leibniz, the German philosopher, who advised Peter on the meaning and purpose of the collection, urged that the displays should “serve not only as objects of general curiosity, but also as a means to the perfection of the arts and sciences.”

But Peter’s subjects didn’t necessarily want to be modernized. The new laws struck them as godless and obscene. Many began to doubt that Peter was really their tsar. Preternaturally tall, with a small head perched atop an unusually long torso, afflicted with a variety of tics and tremors and subject to sudden changes of mood, some said Peter resembled a monster himself. Like foreigners, he smoked tobacco and wore frocks; rumors began to go around that he was an impostor, switched at birth with a German baby or that he was a Swedish barber in disguise. Through a change in the calendar, some argued he stole eight years from God; he was the Antichrist, his followers were devils, and when he sat on the throne, smoke came out of his mouth.

Peter met the skepticism with contempt. While assembling his collection of curiosities, Peter wrote to Leibniz to complain about his fellow Russians: “If I wished to send you humans who are monsters not on account of the deformity of their bodies but because of their freakish manners, you would not have space to put them all.”

This is what Peter knew: that anything can happen to anyone, at any time. From the start, his life obeyed the capricious logic of a fairytale. He was raised in a gloomy castle, haunted by the absence of his dead father. When he was young, he was dominated by a wicked half-sister and passed over in favor of a lesser brother. When he was ten, the royal guards rebelled; they burst into the palace and dragged away his uncle and hacked him to pieces. Peter and his brother were brought out onto the palace balcony to calm the crowd. Their father’s best friend went with them and was pitched from the balcony by the guards and impaled on soldiers’ pikes below.

The knowledge that even the emperor was a subject of chance opened Peter up to other identities, other selves. Throughout his life, he collected aliases, nicknames and disguises. At different times he passed himself off as a common soldier, a Dutch peasant, a drummer, an admiral, and a shipwright’s apprentice. When he travelled abroad he hid behind the name Peter Mihailov — Russian for John Doe — and made people in foreign courts pretend they didn’t know who he was, even though they did. At home, outside Moscow, he had special barracks built so he could sleep with his troops and direct pretend battles around the clock. He liked explosions and fireworks; singing and drumming; globes and telescopes; setting fires and fighting fires. He especially liked making things: a bench, an armchair and a rowboat out of wood, a snuff box out of rhinoceros horn, and a chandelier out of bone.

In Russia, as in medieval Europe, carnival was the annual event in which the low became high and the high became low; the world opened up — to different bodies, different genders, and different sexualities. In some ways, Peter’s whole reign was a carnival: He surrounded himself with the short to seem tall, the foreign to seem Russian, the humble to seem eminent and the strange to seem normal. He liked to have his favorite dog, Lizetka, sign his letters with a paw print.

Early in Peter’s tenure, he inaugurated a parallel court with a parallel clergy, called the All-Drunken, All-Jesting Assembly, which was ruled over by a pretend tsar — Prince Fedor Rodomanovsky, the head of Peter’s secret police, who happened to own a bear trained to serve his guests vodka — and a pretend pope. Though the Assembly mocked and rituals of power — and drank, a lot — both exercised genuine authority over Peter, who, in that context, was just an ordinary citizen; he wrote letters to Rodomanovsky, reporting on his activities, boasting about his advancement through various ranks of the army and navy, and asking for approval in important matters. To Peter, true power meant the freedom to become anyone he wanted.

The museum Peter built in St. Petersburg was meant to bring science to a backward country. Instead, it became a reflection of the corridors of Peter’s restless mind. He took great care and spent an exorbitant sum of money putting it together. On his trips abroad, in between lessons in shipbuilding and parliamentary procedure (while in England, he watched the House of Commons conduct its business from the roof of a neighboring building), he purchased unusual items for his collection. In Amsterdam, he visited the house of Maria Sibylla Merian, the celebrated naturalist and scientific illustrator, and admired the many butterflies and insects she had gathered on her travels to Suriname. From the apothecary and curiosity merchant Albertus Seba, he bought a vast collection of zoological specimens and biological rarities, including a baby elephant and a many-headed dragon, though he missed out on a pair of conjoined baby antelopes, which had been promised to someone else.

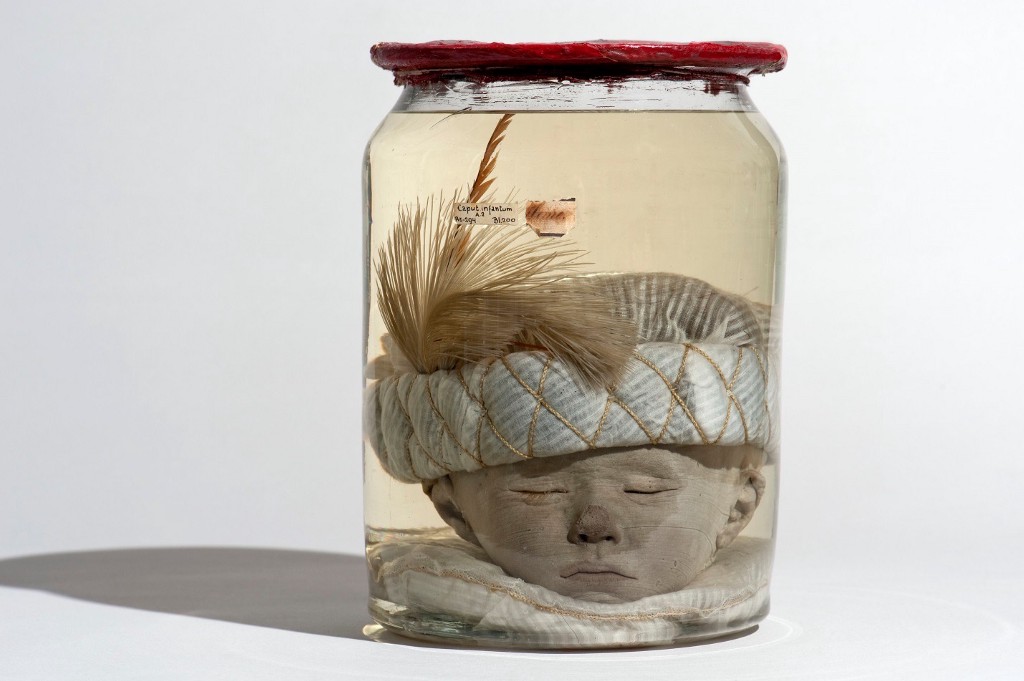

Baby Head with Turkish Hat, Frederik Ruysch, ca 1720

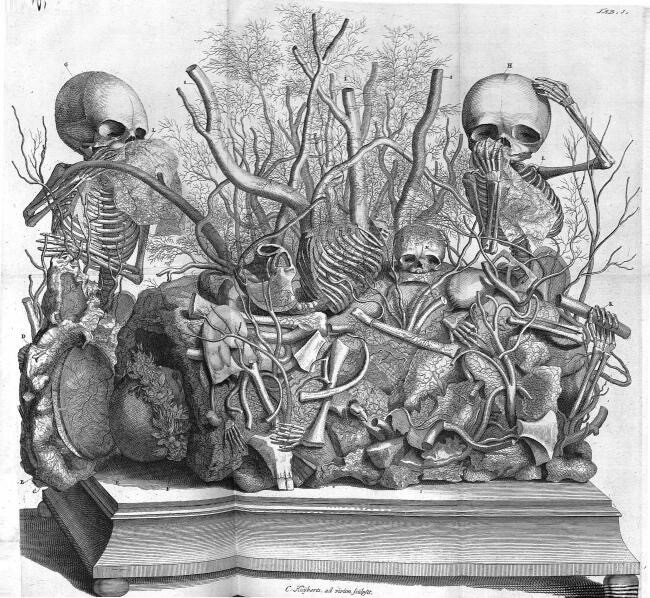

Peter’s favorite supplier of curiosities was a man named Frederick Ruysch, a master embalmer and the greatest taxidermist of his age, who had mastered a secret technique for preserving dead bodies and making them look as if they were still alive. He injected their veins with a special mixture of talc, tallow, wax, cinnabar and oil of lavender. One of his contemporaries observed, “All his injected carcasses glow with striking lustre and bloom of youth; they appear like so many persons fast asleep; and their pliant limbs pronounce them ready to walk.” Sometimes Ruysch took his preserved specimens and arranged them in miniature scenes. His favorite subjects for these displays were the tiny skeletons of fetuses. He liked to pose them, fully articulated, in miniature gardens, whose every element was fashioned out of various pieces of preserved organs. In Ruysch’s hands, blood vessels become corals, gallstones sponges, and the minuscule skeletons explorers on the bottom of the sea.

Cornelius Huyberts, Anatomical Still Life by Frederik Ruysch

Ruysch’s favorite subject was lamentation. In one scene, a skeleton plays a violin, made out of diseased bone, with a bow of dried artery. “Ah fate, bitter fate!” he sings, while another skeleton conducts music with a baton set with kidney stones. A third skeleton, wearing a belt of sheep intestine, grasps a spear made of a hardened vas deferens. In others, the skeletons hold mayflies or scythes.

In another tableau, two skeletons standing on a mountain of kidney stones, surrounded by miniature trees made out of the branching fronds of hardened arteries, weep into handkerchiefs made from abdominal membranes. The message these tiny figures convey is all the same: that their first hour was also their last. Ruysch took special care in preparing the membranes to make to make their delicate blood vessels look like embroidery. They reminded him of Psalm 139: “My substance was not hid from thee, when I was made in secret, and curiously wrought in the lowest parts of the earth.”

When Peter saw the collection, he was reputed to have been so moved “that he tenderly kiss’d a little infant, which sparkled with all the graces of real life and seem’d to smile upon him.” Impressed beyond words by the life-like infants and tiny skeletons crying into their membranous handkerchiefs, Peter bought the whole lot.

It’s difficult to find out much about the lives of the monsters in Peter’s museum, who were illiterate, and lived in extreme poverty. They were made to display their deformities and perform for visitors. Foma, the boy from Siberia, amused guests by picking up money off the floor with his fused fingers. When he died, his body was dissected and his organs were preserved for later study. Although not everyone viewed the living exhibits as fully human, at one point some of the savants at the museum took a scientific interest in their origin. They interviewed one of the children’s fathers to learn more about the circumstances of their birth: “no, there are no other children like our son in the area”; “no, my wife didn’t have any complications during labor”; “no, she didn’t see a convict when she was pregnant.”

The father’s answers speak to a certain weariness. So do the words of the monsters themselves. They complained of cold and hunger, and petitioned for extra clothes and back wages. Some of them tried to run away, and one, an intersexed person, successfully escaped. One visitor to the museum, describing the condition of Stepan, the boy with no genitals, conveys their situation best: “This man, they say, is from Siberia and his parents are simple folk. He would gladly give a hundred rubles or more, if only he could regain his freedom and return to his homeland, from which his parents were forced to send him by the Imperial decree.” The monsters did not think much of the honor of being in Russia’s premier museum.

Wax figure of Peter the Great, Carlo Rastrelli

Stepan never got his wish, and he ended his life as an exhibit in the Academy. In a way, so did Peter. After the Tsar’s death, his successors placed a life-size a wax effigy in the museum. One room away from the bones of Peter’s giant, near to the preserved fetuses he brought back from Holland, it sits there still, wearing the worn boots that spoke to his great thrift and the stockings that he knitted himself, his favorite dog Lizekta at his feet.

Inset images: Foma Ignatiev, drawing from the 1830s; Cornelius Huyberts, Anatomical Still Life by Frederik Ruysch, from Opera Omnia, Amsterdam, 1720.

A New Year's Resolution

After a week or two of mental rest and emotional easing, of public withdrawal and private return, of outward quiet and inner recomposition, of forward blindness and rearward clarity, of not forgiving and forgetting but of remembering and reckoning, and of peace-making, I will hold myself to a single resolution: to be a gracious and subservient subject of the Great and Fearsome Sandra — Sandra the Hideous, Ripper of Faces — and to accept, with humility and respect, the new order into which I expect to return.