Voyager

by Alice Bolin

It was a strange December night in Greater LA when Hawaiian monsoons blew the storm of a decade to our shores and we remained, simply, confused. With global weirding, all our weather patterns have sprouted prefixes: Superstorm, meet the megadrought, Godzilla v. Mothra. In Los Angeles, a city mostly devoid of weather other than desperate winds in early fall, natural phenomena are often framed as conspiracies to hinder traffic. I took the 10 freeway that night going west, against traffic, so the drive was fast and easy despite the weather.

I was going to Pomona, one of Los Angeles’ formerly stately, currently dusty annexes. You can picture it in the twenties, orange groves tucked against Mount Baldy — the very high, sometimes snow-capped mountain that is visible on a clear day behind downtown Los Angeles, making the metro area seem all the more like a collage of scenery pictures cut from an old issue of Ideals magazine. Pomona is home to the green, sprawling grounds of the Los Angeles County Fair and an old fashioned, brick-road downtown with a large district of antique stores that really hammers the point: here’s how the past holds up.

All this is to say, it was a damp, dreamy night in a dimension neighboring reality. I was in Pomona to see Jenny Lewis and Ryan Adams at the Fox Theater downtown, an art-deco relic from the first days of motion pictures. It was the second time in 2014 that I had seen Lewis in concert, and I am not about to apologize for that. She and her band Rilo Kiley have been my constant musical companions since I was a teenager. They made the sweetest of emo for the emo-est of girls. Lewis closed her set with “With Arms Outstretched” from The Execution of All Things, Rilo Kiley’s beloved 2002 album that is a masterpiece of naïve moping. The nostalgia in the room was palpable. Many of the women around me clutched their hands over their hearts with ardor. But when I stopped singing along and listened, I was surprised to find that Lewis had rearranged the song, transforming its fuzzy indie vocals to gospel harmonies, swelling to an a cappella finale. “Damn,” I thought, looking at Lewis in her white airbrushed leisure suit, thirty-eight years old now and singing a song she wrote when she was twenty-six. “She sounds better than ever.”

I was made aware looking around the crowd that night that I was part of a generation: teenagers who were listening to sad music in 2002. These were the exact people who would be in the crowd in twenty-five years when Lewis and Adams mount their grandparent rock tour of the nation’s minor league baseball stadiums. As a fourteen year old in Idaho, I wore out Adams’ 2001 album Gold, a folky, alt-country easy listening pop record with lyrics designed to make a fourteen-year-old feel deep. It prompted me to look up “La Cienega” in a Spanish-English dictionary, with no luck.

In tenth grade, we had an assignment to bring in song lyrics we thought could pass as poetry, and I brought in Adams’ “Sylvia Plath.” I hold that story in my heart because I became a grown-up poet; yes, I should have just read Sylvia herself. But it seems like my urge in bringing in the song was the same as Adams’ in writing it: to flatter myself by identifying with a temperamental genius. Adams is known for being prickly and unpredictable, because of incidents like kicking an audience member out of a gig for yelling “Summer of ’69!” Adams still has a reputation as a huge dick, but at the show in Pomona, he seemed more cranky than volatile. After growing impatient with people calling out requests for songs, he said, “I know this sounds crazy, but we actually talked about this beforehand, and we decided what songs we’re going to play.”

Adams is forty now, and he has mellowed into more of a regular dude, not a tortured artiste. He was diagnosed with Meniere’s disease, an inner ear disorder triggered by flashing lights, which has forced him to take better care of himself. “You can’t drink coffee, you can’t smoke cigarettes, you can’t drink alcohol, you need to exercise, you can’t eat salt,” he told Stereogum. “You have to sleep. You’ve gotta get eight hours.” He married Mandy Moore. He started his own record label and recording studio, Pax-Am Records, where he has gotten himself a regular full-time job: he writes, produces, and collaborates there every day from four in the afternoon to midnight. Out of that excess of material he created Ryan Adams, one of the underrated albums of 2014.

In 2011, Adams worked with the Beatles producer Glyn Johns on the subtle, acoustic album Ashes and Fire; Ryan Adams was the guitar album Adams wanted to make when he was producing for himself, and this satisfies me because my greatest vice is comparing music to Tom Petty. There are licks all over Ryan Adams, and it displays Petty and his power pop brethren’s equal commitments to hooks and angst. There are nods to eighties basement rock like on “Kim,” where Adams’ guitar sparkles out of tune across the track. “Nothing’s ever going to be more important to me than the Wipers, Hüsker Du, the Replacements,” Adams said to explain why he made a pure rock record, but he didn’t convince. Ryan Adams hasn’t charted, and critics weren’t that into it either.

“It was at a point in between bands, and having recorded many versions of these songs, I was a bit clueless as to what I wanted it to sound like,” Lewis said of her 2014 album, The Voyager. “I was screaming for a spirit guide, and it showed up in the form of Ryan Adams.” The Voyager has been a triumph for Lewis, her first top ten album and the best work of her career. She direct messaged Adams on Twitter to get his advice on a song, which led to Adams producing the whole album. They recorded it at Pax-Am in a week and a half. Lewis’ earlier solo albums were inconsistent — endearing, corny, and stylistically all over the place. Adams’ guiding hand is evident all over Voyager, which is another guitar album, another homage to late seventies rock, but more groovy than Ryan Adams. Is it a coincidence that Tom Petty had his first number one album in 2014, Hypnotic Eye? I mean, probably.

In Pomona, Adams surprised the audience by covering Lewis’ “She’s Not Me,” a song she had just played a half hour earlier. It’s a standout from The Voyager, a sad song with a thumping beat that sounds — and I mean this in the best possible way — like Hall and Oates. Adams sang it in Lewis’ key too, pointing up what had been obvious the whole night: his voice is remarkably true, much more so than on his records. He is a choirboy and Lewis is a choirgirl and they are both throwing away notes to sound like Tom Petty. And Tom Petty is a choirboy who is throwing away notes to sound like Bob Dylan. Listen to “Fault Lines” from Hypnotic Eye, though. More often now, Petty sings not like Dylan but like their friend George Harrison, in a gentle croon.

Petty, Dylan, and Harrison, along with Jeff Lynne and Roy Orbison, created that most utopian of rock and roll projects, The Traveling Wilburys, a true supergroup who made two albums in the late eighties and early nineties, just, bafflingly, for fun. Lewis covered their song “Handle with Care” on her first solo album Rabbit Fur Coat with her fellow indie cuties Ben Gibbard and Conor Oberst, in acknowledgement that if you are going to sing a Wilburys song, you must invite your most famous friends to sing it with you. All Wilburys songs indulge in wordy rhymes, like on “Handle with Care”: “Been stuck in airports, terrorized/Sent to meetings, hypnotized/Overexposed, commercialized.” See also: Lewis on “The New You” from The Voyager: “You struggle with sobriety/Dreams of notoriety.”

The most notable lyrical references on The Voyager are to eighties heavy metal — Metallica, Slash, and the Headbangers Ball — evoking Lewis’ childhood. The Traveling Wilburys albums were released when Lewis was a teenager, but they are a direct line to the music of the seventies, when Lynne made the Xanadu soundtrack, when Harrison made his solo albums, when Petty made Damn the Torpedoes. And when Lewis was born. Like Adams, Lewis is sadder but wiser in her late thirties, and The Voyager is a more truly vulnerable album than Lewis has ever made — it’s about marriage, compromise, baby envy, and the death of her father. “You’re thirty-nine and looking at your friends and parents are dropping dead and some of them are dropping dead, starting early, it’s a weird time,” Adams told Stereogum. “It’s kind of like that movie The Big Chill but everyone’s wearing Dinosaur Jr. shirts.” It makes sense that at a time in their lives when they are cleaning up and taking stock, Lewis and Adams use their music to reach all the way back. Nostalgia is a search for origins and identity. The Traveling Wilburys were a nostalgic band too, and they weren’t longing for the height of their stardom; they were longing for the music of their childhoods, nineteen sixties car songs and Buddy Holly.

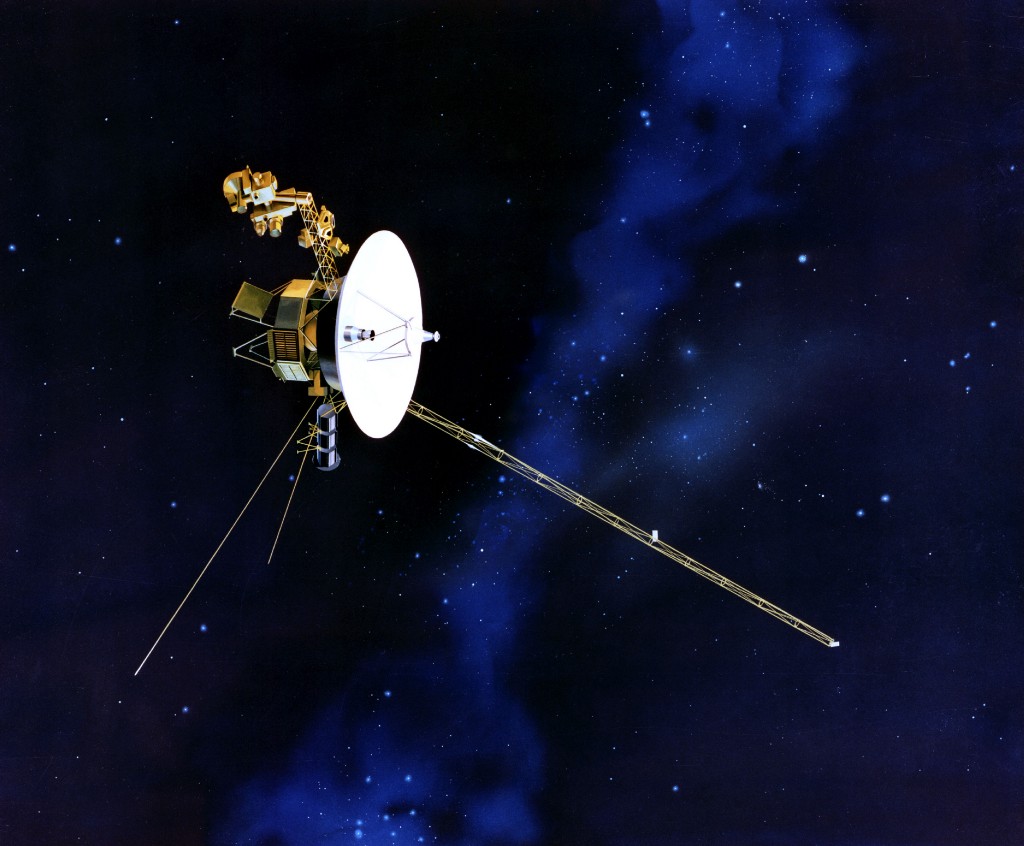

In 1977, the year after Lewis was born, NASA launched its exploratory spacecraft Voyager I, carrying the Golden Record, an artifact intended to communicate the entirety of life on earth to any beings who might encounter it — speaking of utopian projects. In September 2013, NASA announced that the Voyager had broken through the heliopause and entered interstellar space, the first spacecraft ever to do so. “The Voyager’s in every boy and girl,” Lewis sings of the event on the title track of The Voyager. “If you want to get to heaven, get out of this world.” I saw Lewis in Los Angeles in August with my younger brother, and we listened to her play the songs we used to sing along to as teenagers, when I would drive us to Barnes and Noble and Pizza Hut. It was nostalgic, but I didn’t want to go back. Looking at my brother, the moment felt fulfilled, and I was thankful just to be there, in the future of my past.

Photo by NASA

Never Better, a collection of essays from writers we love, is The Awl’s goodbye to 2014.

Get Out of the Water

by Leah Reich

The thing about 2014 is that, despite what we have been led to believe all our lives about time and calendars and holidays, we can end it whenever we want to. I live in the Bay Area so you’re maybe thinking: Is this some disruption bullshit? Is this about Gaia and our earth rhythms? I mean, in a sense yes, but so is everything these days.

At the end of 2013, sometime at that point in December when we float hopefully toward the clean slate of the new year on a sea of “best of” lists and cries of “fuck this year, it’s been the worst,” I decided that I’d had enough — of 2013, of all the things that had happened in the months that defined the year, of the way I felt. Contrary to popular belief, last year was just as terrible as this or any other year. People were awful to one other. We lost jobs, became ill or injured, disappeared, died. Authority figures and those in power abused those below them and got away with it, were even celebrated and pushed onward to greater heights in their lives. We spent that chunk of time doing what we do every year: Thinking each separate year is somehow distinct from the one that precedes or follows it, thinking the next one would be better.

And so one day I decided that was it, time to wrap 2013 up and move along. We were going to do better, or at least I was, and anyone who wanted to join me was very welcome. Some random day in December, I declared my own 2013 had ended.

I thought about how a year or two earlier, on New Year’s Day, I’d run into the frigid Pacific Ocean on a beach with a bunch of other lunatics, and how the cold water had woken me up in ways I didn’t know were possible. The ocean was vast and we were just at the very edge of it, screaming and laughing. For once I thought: There has never been a better time to be alive than right this minute. When we came out we bundled up, drank bourbon and champagne, laughed at the babies and kids who rolled in the sand with us.

That’s all there is, really. We can get out of the water any time we like. It’s alright to do it alone, but it’s probably better if we start doing more things together.

Photo by Paul Vincent

Never Better, a collection of essays from writers we love, is The Awl’s goodbye to 2014.

The Black Void of the Moon

A big part of the widespread feeling that things are getting worse is simply the slow, sad unfolding of adulthood. That is, things were what they were all along, but the more unpleasant bits were mercifully kept from us. Eventually, inevitably, one comes to pick up the newspaper. What a drag! What a mess. A layer of poisoned sludge over every inch of every surface — a thick, rank coating of the most incredible bullshit and disaster smothering everything, it’s unbelievable. As a teenager, you encounter the famous bon mot of Mohandas Gandhi, his response to a reporter who’d asked him what he thought of Western Civilization — “I think it would be a very good idea,” he replied — and you laugh darkly, knowingly.

Only Gandhi never said that, probably; some journalist made it up in 1967. The limitless new universe of your own ignorance heaves into view. Worlds upon worlds. In your most intense certainty you will be proved wrong, wrong and wrong again. You won’t even need the unending deceit of dirtbag politicians or thieving corpocrats or faithless lovers or friends in order to be proved wrong, a lot of the time, often — so often that conviction itself is an obvious liability, to be avoided whenever possible. Not until every vestige of world-weariness has been scraped from what remains of your intelligence, your critical faculties and even your emotions, and you no longer pretend to know anything at all — maybe then you return to the state of a child, who knows nothing and doesn’t want even to pretend to know, who is ready to accept every new moment as a surprise.

The Waterboys’ signature tune, “The Whole of the Moon” (1985) is a tribute to the natural majesty and radiance of a person known to the composer, Mike Scott — a close friend, maybe a colleague; Scott has never quite revealed whom it is he’s addressing. He contrasts the instinctive, innocent brilliance of this friend with his own intellectualism in this song, which seems to me to be the definitive cri de coeur of that cultural moment, long ago: “I spoke about wings/you just flew.” Scott’s elegantly quavering voice delineates a deeper message, too, extrapolating the futility of his attempts to make sense of the world through reason, intelligence — the way we’ve all been taught — out toward a broader interrogation of Enlightenment principles, the faux-basis of faux-Gandhi’s faux-Western Civ. Best of all, Scott entertains the possibility that accepting all there is to accept of the moon, rather than (with apologies to the management) quarreling with it, or attempting to understand it, might result in a better outcome; something closer to the truth of things.

Michael Collins is the astronaut who didn’t land on the moon in July of 1969, but stayed alone in orbit aboard Apollo 11’s Columbia for twenty-some hours, very much afraid that he would be returning to Earth alone. There was considerable doubt at NASA whether the engine of the Eagle lunar lander would be able to ignite on the moon, so that it could bear Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin safely back to the mothership; if it failed, Collins would have to leave them behind. Armstrong later said he’d reckoned their chances at about fifty-fifty. Collins wrote: “If they fail to rise from the surface, or crash back into it, I am not going to commit suicide; I am coming home, forthwith, but I will be a marked man for life and I know it.”

Nixon had a terrible speech all ready for that eventuality — some kind of weak nonsense contrasting exploring in peace vs. resting in peace.

For forty-eight minutes of each two-hour orbit, the “lonely lifeguard” Collins lost all radio contact as his craft traversed the dark side of the moon. All the way through the darkness he sped. Charles Lindbergh would later write to him: “You have experienced an aloneness unknown to man before.” But that isn’t how Collins felt about it at all, as he explained in his 1974 memoir, Carrying the Fire: An Astronaut’s Journeys.

I don’t mean to deny a feeling of solitude. It is there, reinforced by the fact that radio contact with the earth abruptly cuts off at the instant I disappear behind the moon. I am alone now, truly alone, and absolutely isolated from any known life. I am it. If a count were taken, the score would be three billion plus two over on the other side of the moon, and one plus God only knows what on this side. I feel this powerfully — not as fear or loneliness — but as awareness, anticipation, satisfaction, confidence, almost exultation. I like the feeling. Outside my window I can see stars — and that is all. Where I know the moon to be, there is a simply a black void; the moon’s presence is defined solely by the absence of stars.

One of the weirdest things about “how much worse things are getting” is that you see and gasp at all the horrors and dangers all around us from a position of boggling comfort and ease, a delicious perch whence you can call a car or order a banh mi or discover the names of every movie Hermione Gingold was ever in, and barely have to move a muscle to do it. This everyday combination of ease and terror that constitutes the chief First World Problem is just absurd, eye-crossing. Over the falls we go, in our plush canoe!

We don’t know whether the engine down there will ignite, as we speed through the void: we don’t and we won’t. The matter is out of our hands. It seems there’s no way out. And there’s not.

It depends how one is constituted, but the various balms we have, of music, love, philosophy, religion, friendship, literature and art, of all the kinds of understanding we can hope for or try to have, might serve to bring us all to the other side again. Surely one should be ready to come back into the light. Just in case.

My windows suddenly flash full of sunlight, as Columbia swings around into the dawn. The moon reappears quickly, dark gray and craggy, its surface lightening and smoothing gradually as the sun angle increases. My clock tells me that the earth is about to pop into view, and I prepare for it by positioning my parabolic antenna so that it points at the proper angle.

Never Better, a collection of essays from writers we love, is The Awl’s goodbye to 2014.

Photo by NASA

The App That Allows You to Find People You've Crossed Paths With

by Awl Sponsors

Most dating apps simply connect you with potential matches you haven’t met yet. Happn is the only app that connects you with people you’ve already crossed paths with with — people with whom you actually want to risk wasting your time.

Sounds kind of exciting, doesn’t it? Here’s how it works.

Happn uses GPS tracking to present you with a list of people near you. It tells you whether you’ve crossed paths with them once or several times, giving you a map of roughly where you crossed paths, their photos, name, age and profession.

Remember that stunning brunette reading George Saunders at your local coffee shop? The one you’ve been secretly eyeing for weeks? “Like” them secretly with the Heart button: they won’t find out unless the interest is mutual. And if you wish to be noticed, charm them to send them a notification. And if they like you too, you can start a conversation.

Happn also cuts down on the creep factor of other dating apps. People you don’t like will never be able to send you any messages. And if you don’t want to see a person on happn anymore, you just have to click on the “Cross” button.

Happn is a safe and fun way to re-connect with the people you’re interested in. According to The Guardian, “…any pursued partner has the power to accept or reject advances without coercion or scrutiny; rejected suitors are not spurned so much as politely unanswered. Mutually attracted couples can, however, initiate the connection with privacy and without shame.”

So what are you waiting for? Click here to give Happn a shot.

New York City, December 22, 2014

★ “I can’t see the clouds,” the three-year-old said, looking up from breakfast and out at the undifferentiated gray. “They’re mixed up in the sky.” A dullness, thinner than a fog, lay over everything. A pigeon, steaming breath, sidewalk concrete, a shineless food cart — all were the same color. So was the light, while it lasted at all. A blowing, soaking mist fell on the commute in the dark.

Drink the Vinegar

When I was a kid I used to get yelled at for sucking on lemons. “IT’LL ROT THE ENAMEL OFF YOUR TEETH!” my mom would say. (A cursory Google search indicates that she was right and it’s totally possible that my teeth are enamel-free stumps at this point.) I have always had an affection for sour things; I prefer the sour candies to the sweet, and to this day my vinaigrettes are much more sour than a properly trained cook would make. While my love of sour citrus has not waned, it has been joined by a deep fascination with another souring agent: vinegar.

Vinegar is typically made by allowing the natural bacteria in various alcohols (wine, cider, sake) to spew out acetic acid over long periods of time. It is an ancient, mystical liquid, and it is one of the basic building blocks to making good food.

The key to all of my favorite cuisines is balance: the right amount of sweet, sour, spice, fat, salt, and umami. Foods that you wouldn’t think have more than one or two of those flavors become much more delicious when you start adding others. Take applesauce, for example. Seems like it shouldn’t be much more than sweet, right? But my favorite applesauce has all of those flavors: honey and the apples for sweetness, sure, but also butter for fat, more salt than you’d think, cinnamon or allspice or clove for spice, and apple cider vinegar for sourness. It doesn’t taste salty or sour but fuller, more flavorful, more restaurant-y. It’s better because you’re boosting the flavor by adding little hits of supporting fundamental seasonings.

I always have at least a half-dozen types of vinegar on hand. There’s no reason not to; vinegars are usually pretty cheap, and they never really go bad. (They might, after a few months or a year, develop a little cloudiness or sediment; this may look sort of gross, but does not affect the flavor at all, nor does it make the vinegar unsafe to use.) Here is a rundown of common vinegars and when to use them.

Wine Vinegar: The cheap stuff will usually come in either “red” or “white” varieties; more expensive kinds will say the varietal of grape, just like wine does. I do not recommend buying wine vinegar at all, but that’s not because I don’t like it: It’s ridiculously easy to make, and homemade wine vinegar is CRAZY DELICIOUS. That said, I sometimes have the cheap stuff on hand. Red wine vinegar matches especially well with sweeter citrus, like orange or grapefruit or pomelo, in vinaigrettes. White wine vinegar is ideal for boosting the flavors of creamy pale things; it’s my go-to vinegar for egg salad, for example.

White Vinegar: I love plain, no-nonsense Goya brand white vinegar. It’s one of my most commonly used vinegars simply because it has no added flavor besides “sour,” so if I’m experimenting and know that a dish needs something sour but I’m not sure what flavors will work with it, bam, white vinegar. It’s also usually the cheapest, so it’s great for preparations that require a lot of vinegar, like pickling.

Apple Cider Vinegar: My second favorite. I buy the Bragg brand, because it’s unfiltered — it doesn’t necessarily taste all that different from Goya’s cheapo stuff, but it’s the cheapest way to get unfiltered vinegar, which you can use in the making of your homemade wine vinegar (more on that later). Cider vinegar is way more flexible than you’d think; it’s a touch sweeter than white vinegar but nowhere near as sweet as, say, balsamic, which makes it great for everything from vinaigrettes to pickles. It also is the best vinegar to use in desserts, due to its slight fruitiness. I especially like it with Southwest flavors — cumin, chile, corn, black beans, that kind of thing. Weirdly works as a substitute for lemon or lime juice in a lot of cases.

Balsamic Vinegar: Very nineties, but still has its uses. Balsamic comes in two types: incredibly cheap and incredibly expensive. The expensive stuff is thick and sweet and rich and comes in tiny delicate bottles and is used as a sauce by itself, not to be mixed with other ingredients. It’s very good and I never ever have it because it costs like fifty dollars a bottle and, like, come on. Cheap balsamic vinegar tastes like the suburbs. It’s made by mixing grape juice with some stronger, plain vinegars, to taste like a faint echo of the real stuff. It’s sort of thin and sweet and uncool these days, I think, but every once in awhile I want a god damn Greek salad with romaine and kalamata olives and feta and cucumbers and tomatoes and balsamic vinaigrette, so I’m pretty sure there’s a bottle of garbage “aceto balsamico di Modena” (this means “cheap shit” even though it’s in a foreign language) in my cabinet.

Rice Vinegar: Rice vinegar, along with white and cider, is the variety that I always, always have on hand, because it’s just so versatile. It comes in a few different types. Standard rice vinegar is very similar to white vinegar, with hardly any extra flavor. Seasoned rice vinegar usually has some sugar in it, and is the kind I usually use; pretty much any stir-fry with Chinese or Japanese flavors gets a splash of seasoned rice vinegar near the end of cooking. And there are a couple rarer varieties, like red rice vinegar, which I’ve never used, and black rice vinegar, which is made from black glutinous rice and is INSANE. If you have access to a Chinese grocery store, go get some black rice vinegar; it has this kind of malty smoky flavor and makes some of the best vinaigrettes you’ve ever tried. Also it’s great by itself as a dipping sauce for dumplings.

Sherry Vinegar: One of the sweetest types of vinegar, sherry vinegar is typically pretty expensive but worth splurging on. It comes from Spain and unsurprisingly works well with Spanish dishes (try it with a vinegar-based potato salad!), but I like it to emphasize the sweetness in certain fruits and vegetables. If you’re sauteing, say, a bunch of bell peppers, a splash of sherry vinegar will bring out their sweetness without making them cloying. It’s also good with fruit, which makes it a great choice for both fruit salads and for fruit gastriques. Here is a good primer on gastriques.

Champagne Vinegar: Basically tastes like good white wine vinegar. It’s not, like, fizzy or anything.

Malt Vinegar: Made from malted barley, this is basically beer vinegar. It’s rarer here in the States than in, say, the UK and Canada, but it shouldn’t be, because it’s really very good! It’s much more mild than cider, white, or rice vinegar, and a little sweet and smoky as well. It makes a lovely vinaigrette but its best use is also its most common: sprinkled on top of french fries.

There are plenty of other vinegars, but you either won’t often see them or don’t really need to mess with them. Raspberry vinegar, for example, is gross as hell — sweet and perfume-y and bad. (If you want to make a raspberry vinaigrette, use a neutral vinegar like rice or white and mix it with raspberry juice.) Coconut vinegar is delicious but rare. Apparently New Zealand makes a kiwi vinegar which sounds very intriguing but I’ve never seen it in the wild, so.

One of the most important things to know about vinegar is that you can make your own, and that it is so easy to do that it doesn’t even really count as a recipe. Wine vinegar is the easiest to make, and the main ingredient is probably one that you have around anyway. Here’s how it works.

If you have some leftover wine, or a bottle of wine that you don’t really like much (for example, maybe you got talked into buying some Finger Lakes wine at the Grand Army Plaza farmers market, and thought, oh cool, local-ish wine, maybe it’ll be good, I mean, the grapes these guys grow are delicious so maybe their wine will be good too, and then you drank it and it was disgusting even to someone who knows nothing about wine, like just on a basic “this is not pleasant to imbibe” level), you’re pretty much set for ingredients. Pour the wine into a clean glass container of some sort. A mason jar is, unfortunately, perfect for this, even though a mason jar is typically the most irritating possible vessel for anything. Take a paper towel — or cloth, just nothing airtight — and put it over the top of the jar and secure it around the neck of the jar with a rubber band.

Put this jar in a cabinet or some other dark place. In a couple weeks, you’ll see some gross stuff floating on the surface of the wine. Do not disturb it; this is called the “mother.” Continue to do absolutely nothing to this jar of old wine for another couple months. The gross stuff will get grosser and then eventually sink to the bottom of the jar. Every few weeks, taste the old wine to see if it tastes like old wine. The best way to do this is with a straw; poke the straw through the gross shit and into the wine and put your finger over the exposed end of the straw to trap some of the wine in the straw, then lift it out and taste. It will taste like old wine for awhile, and then suddenly, it will taste like vinegar. REALLY GOOD vinegar. (You could also speed this process up by adding a touch of store-bought unfiltered vinegar that’s labeled “with mother” to your old wine. Bragg is probably your cheapest bet since it costs like six bucks and is both good vinegar and can be used to make more vinegar. Thanks, Bragg!) Anyway, when the old wine tastes like vinegar and not wine-y at all, you can filter out the gross stuff by pouring it through a sieve. Or, if you’ve used cheesecloth or a bit of cloth instead of a paper towel on the top of the jar, you can just turn the jar upside-down into a bowl and let the vinegar pour out, trapping the gross stuff in the jar.

This method (“method,” really, because this recipe is basically just “be disgusting and let your old wine rot for a few months”) works with any kind of wine. Champagne works, too, and is a great way to use old flat champagne instead of pouring it down the sink. And what a coincidence, we are now in the party season where everyone is drinking wine and champagne, and some of that wine and champagne will remain in half-full bottles in your house, and you will think gross, now I have to pour this down the sink. But wait! Don’t! Pour it into a glass jar instead and forget about it for a few months and you will have truly spectacular vinegar that would cost you literally dozens of dollars at your local specialty market, for free.

Most of being a good cook, I think, is learning how food should taste, and knowing how to adjust your food so it tastes that way. A good cook will be able to taste a soup or sauce, and if it doesn’t taste right, will know WHY it doesn’t taste right, and what it needs. Does it need a pat of butter or swirl of oil? Does it need a touch of sugar? A hit of cayenne? Often, what it needs will be a quick pour of vinegar. And if it’s vinegar you made yourself, well, that’s some pretty impressive cookery.

Photo by Mattie Hagedorn

Dear Kids

by Paul Ford

I went digging around tonight to find a quote from the preface to a Barbara Tuchman book. I tried to step gingerly around the apartment–you guys are three years old now, and you’re asleep and both have colds–but I kept knocking books off the shelves, because there are too many books, photos, toys, miscellany.

“Why,” asked my wife, who was sitting up in bed with her phone, and also has a cold, “are you knocking books off the shelves?”

“I need something with a red spine,” I said.

The quote was not in The Proud Tower after all (the spine was burgundy, my wife pointed out) or The March of Folly. But by excluding them I was able to boil down the semantics until I found what I was looking for on the Web, in the preface to Tuchman’s book Practicing History. This is the quote:

On June 18, 1940, the day Hitler entered Paris, I was married to Dr. Lester R. Tuchman, a physician of New York, who not unreasonably felt at that time that the world was too unpromising to bring children into. Sensible for once, I argued that if we waited for the outlook to improve, we might wait forever, and that if we wanted a child at all we should have it now, regardless of Hitler. The tyranny of men not being quite as total as today’s feminists would have us believe, our first daughter was born nine months later.

You have to consider that era. Here’s an old radio news show, The March of Time, from January 1st, 1942–seventy-three years ago. The title of this episode is “Every Continent on Earth Lay on the Scales of Destiny!”

Purple, yes. But this was not an ironic or overstated title. Every continent on earth, at that time, lay on the scales of destiny. That was a reasonable statement.

As I was poking through the shelves I found this other book, The Doomsday Dictionary, one of my favorites. No one knows about this thing; it’s one of those used-book shop finds that you make when you’re sixteen that makes an impression. It’s a dictionary of terrible things, written by a psychiatrist and a poet, published in 1963. I.e.:

Mushroom Cloud

The hallmark of a nuclear burst. Truly a cloud: it is wet, cool and sometimes capped with crystals of ice. The fireball (q.v.) has expanded so rapidly that its temperature falls to a point where the water vapor in the air that has been updrafted condenses into droplets. These droplets are too misty to create rain, but they are large enough to reflect the white light of the sun. The mushroom shape has been formed by the initial column of material sucked up between the bust and the material’s outward swirling once within the fireball. The shape is fixed momentarily against the surrounding shock front. The cloud, now a billowy cumulus, passes upward through the subfreezing temperatures of the tropopause, being blown slowly shapeless by the winds. An amorphous mass, it reaches into the stratosphere. The heavy particles of the burst are far below, falling in the vicinity of ground zero. The cloud now contains the radioactive microdusts and gases of subsequent global fallout (q.v.). (194)

Note also 1963 was the year the March on Washington happened. Jean Shepherd (best known today as writer and narrator of A Christmas Story) went down on an old rickety bus and attended.

It’s like you are suddenly with a million old friends…a strange feeling…and there wasn’t one moment that was phony at all…one of the great moments, we walked through the grove of trees…You sure can’t tell who it’s going to be who’s going to come across.

So you’ve got mushroom clouds and Jim Crow segregation laws in action in the South, and the kids who are marching, the young ones, white and black, are the ones born around the time that Hitler was conquering Europe. And they were right. The March on Washington is the sweetest revenge the world could have taken upon Hitler.

The idea that there is anything especially bad about 2014 is temporal narcissism. We just live in an age of countless opinions. We are just starting to get used to it, this idea that we can document everything. We can document it but we can’t begin to interpret or understand it.

You are two sweet, small people with oval faces. How do I prepare you for what’s coming? This week: An angry, mentally unstable man shot two policemen in their cars in a kind of retaliation for the strangulation of a man by police many months before. Some people blame the Mayor, who worries that his black son will be injured by policemen. We’ll put cameras on cops now. That feels like it will fix everything but it will probably just introduce a new class of ambiguities.

And next week: something else.

I’m worried about those things but more worried about getting you out of bed and dressed in the morning. I’m worried about looking out the window one day and seeing a column of fire but more worried about teaching you to be sad when I could be teaching you to be happy. I’m worried about the college teacher writing for the New York Times who also works as a waiter. I want you to have careers and cats; I want you to have apartments without roommates in your thirties.

It upsets me when we are talking and playing that sometimes one of you will run, unprompted, and get my phone and bring it to me, because you want me to be happy. Here’s your phone, Daddy. As if I was looking lost without it.

It feels strange to say this, but I was your year. Along with your mother, the ladies who run the daycare, and the people at the supermarket on Cortelyou Road. I made your year with grilled cheese sandwiches and putting on shoes. I made it pushing around a stroller, going to coffee, tweeting nonsense, doing freelance work. So for 2015 it will be…more. No matter how nice it would be to squirm out of it, to point and pontificate, I am someone else’s 2015, and have a lot of work to do.

Photo by Jason Permenter

Never Better, a collection of essays from writers we love, is The Awl’s goodbye to 2014.

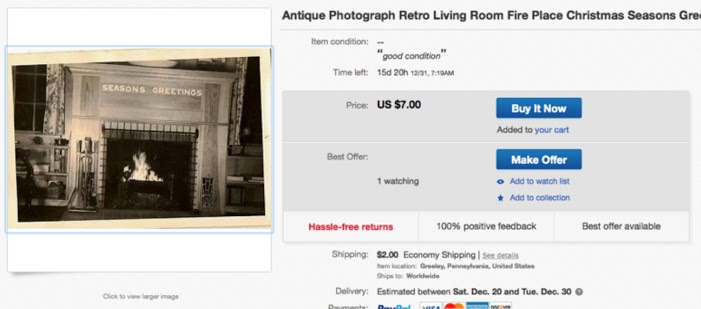

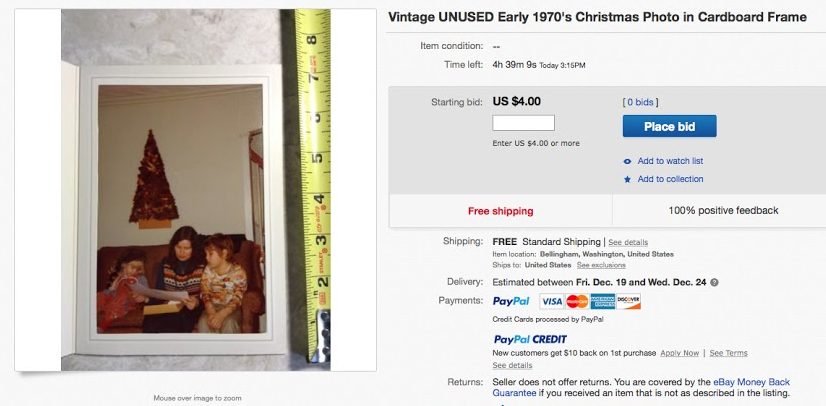

Other People's Christmas Photos

by Andrea Volpe

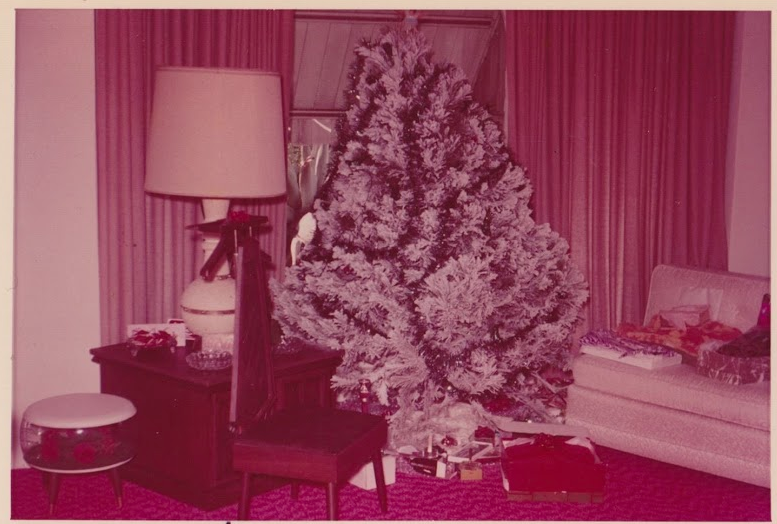

If you search the terms “Christmas” and “snapshot” on eBay, you will get a list of more than one thousand photographs. Think Diane Arbus with an Instamatic. In one shot, two wide-eyed girls in matching striped pajamas stand beside their matching dolls. In another, the girls, still in pajamas, sit before a decorated tree with their brother, who is wearing his Boy Scout uniform. Then there are the sketchy Santas. So many tinseled trees I lost count.

These images were never meant for sale, or to be seen by strangers, but here we are. Now, thanks to the widespread assumption that anything and everything can be sold on the internet, images of someone else’s Christmas are for sale to the highest bidder. (That said, for the most part, no one’s buying; a great number of surveyed images have exactly zero bidders.) A market, by definition, is where people assemble to sell and buy commodities. But that doesn’t mean they agree about the nature of the thing being sold or bought.

The Christmas tree is the money shot of the genre. Christmas trees with tinsel. Christmas trees with children. With presents ready to be opened. After the presents are opened. (As in early battlefield photography, it’s hard to get an action shot.) A surprising number of trees beside a TV set. A television set! How quaint. But not as many cats as you might expect, and not that many crèches or wise men, either.

Chalk it up to inexorable progress that digital has made markets for things that hardly had markets before, scaling up the garage sale into something enormous and rational. This is fine when it comes to utilitarian objects like, say, Pyrex. Everyone needs mixing bowls; if they are from 1978, fine. But we are talking about a market for snapshots that were supposed to be so personal and precious that there shouldn’t be a market for them. What is being sold and being bought here, exactly?

On the sellers’ side, the clues are in the captions. Take for example “Old Antique Vintage Photograph Dad With Children Christmas Tree Train Set Gifts,” Or even better, “AWKWARD FAMILY CHRISTMAS PHOTO TREE TINSEL FASHION VINTAGE SNAPSHOT PHOTO.” All caps says it all. To paraphrase Tolstoy, what family at Christmas isn’t awkward?

These photographs need their captions, because now that they are detached from the context in which they were made, they are virtually meaningless. The code words “retro” or “antique” or “vintage,” appear with remarkable regularity, as in “Old Vintage Photograph Gorgeous Christmas Tree All Decorated Retro Xmas.” Most often it’s the photographs themselves that are described as “vintage,” and it’s the objects pictured in them, particularly TV sets, that are what’s “retro.”

But retro is the wrong word. These photographs aren’t imitative of the recent past, they are the recent past. Nor are they antique — collectible or valuable because of their age or high quality. The consistency of the captions isn’t accidental. The sellers know full well there’s something pathetic about these photos — a disassociated nostalgia that has to be overcome in order to make a sale, and yet which ultimately stands as the element of the photograph with the most value. The work of art in the age of mechanical reproduction was supposed to not just be economically cheaper, but also emotionally and aesthetically cheapened. Now, in the age of digital reproduction, what was mechanical, multiple, and devalued has become almost unique and valuable.

That doesn’t mean I’m entirely comfortable buying. Scrolling through these pages is like walking through the neighborhood and looking through someone’s living room window for too long. You’re fascinated but you know you’re prying. It’s interesting looking at pictures of other people’s families, until it’s not, and then its sad and a little icky, thinking about what turn of fate separated family photographs from their families. There’s also a strange flicker of recognition that comes from seeing screen after screen of oddly familiar scenes, as if we’re supposed to recognize the people in the photos after all. Is that Aunt Rosalie? Cousin Charlie? Could be. Not sure. The motivation to buy is still complicated: Maybe you want to rescue the people in the photo and give them a home. Or you think the image is really, really cool, or really, really sad, or cool because it is sad.

Even as I was compelled to look at each and every one of these 1,123 photographs, I found myself performing a sort of visual triage as I scrolled through, trying to separate the good ones from the bad ones. I was judging them based on their proximity to or distance from an aesthetic, even as I knew, intellectually, that none of them were any good. Isn’t a discarded snapshot, by definition, valueless?

Maybe not. The only way I could contemplate buying any of them was by arranging them into a typology, where the sum is greater than any single part. Take the Christmas tree. Most of the trees in these pictures make the Grinch’s tree look lush. Individually, they are depressing. But together, in a series, they are arch and ironic. That’s when I started buying Christmas tree snapshots. No people. Just the trees.

It was oddly comforting. If the photos are of a type, then maybe we can find ourselves in them, burnishing our own singular banal experiences — memories of Christmases past — and making them into something more than they were.

I valued the photographs for how they looked, not the specificity of the experience alluded to by the literal content of the image. I could separate signified from signifier. I wanted the photograph because I valued the style in which it was rendered, not because I wanted the tree itself.

Essentially there are two ways to make sense of experiences worth photographing. The first is to think of yourself and what’s happening to you as unique and special, so it’s worth capturing on film (or with pixels). This is the logic of the snapshot, and this is why our phones are now cameras. We are all so very, very special these days that we can, and do, take nearly infinite photographs.

The other explanation is that we are not that special at all, we are merely heeding a cultural formula, one that is bigger than we are, that we learn to see through, and that we imprint on our individual experiences. This is also the logic of the snapshot. We know by cue when something is worth photographing; when we drive by a spot in the road labeled “scenic overlook,” or after we put up the Christmas tree.

Let’s go back to Diane Arbus for a minute — because her deadpan style owes so much to snapshots and because in 1963 she took a picture of a Christmas tree in a Levittown living room. Arbus, who worked in black and white, and William Eggleston, who worked in color, elevated the snapshot into art by distilling its formulaic aesthetic and expressing it as something more. Now, as an eBay shopper, I could see a little like Arbus and Eggleston had, turning the snapshot back on itself. I found images that were sort of like an Arbus and a little bit like William Eggleston’s world: brash, and too-close-up, and saturated with color. I’m still kicking myself for missing out on the best Arbus-like photograph, but I landed a nice Eggleston look-alike.

There was something a little off-kilter about this. The snapshot starts its life saturated with context. Specificity matters more than anything else, so much so that the style of the photograph is virtually unconscious. But give enough people a chance to point a camera at a Christmas tree, and generic conventions emerge. Form follows function: to remember, to commemorate, to document. When that distinct style is appropriated, as it was by Arbus and Eggleston, we become more aware that style in a photograph is something to be deployed, even as their work depended on and even reinforced the boundary between art and kitsch.

The thing that we are most afraid of about our photographs is that they won’t be recognizable, that we will forget the names of the people in the picture, that they will lose context, and lose meaning. We fear that this will make them lose their value. But on eBay, lack of meaning is their most desired quality.

My Best Self Now Is My Worst Self Later

When I scroll backward through my Instagram, I kind of hate myself. Have you looked at anyone’s old Instagram photos? Of course you have, this is online stalking 101. Mine are especially bad. I look at them and I look at the people who actually, at one time, clicked a like button, to endorse this mediocrity, and I question their taste, but not nearly so much as I question my own.

When I moved into my current apartment two years ago I was short on art, so I printed out some of those old Instagrams and stuck them on my wall, in a grid, across from my bed. Then I started to learn about photography. I learned some things about structuring a shot and when the light is just bad (sooner than you think after sunset in New York; in most restaurants and bars, especially at night; but it’s weirdly good next to plane windows) and also how to edit photos with other apps. Every day I woke up looking at those old photos on my wall, and every day I was more embarrassed of my own judgment.

I look at the old photos in my feed periodically, disappointed in myself but also the two or ten or twenty other people who I duped into endorsing each photo with a fat Instagram heart. This one is too blue, this other one is too grainy, this crop is terrible, and this one! This is literally just a picture of my fingers. It is a bad picture of my fingers. Why did I see fit to share this with other people as if it were worth looking at? A cat, a flower, a sunset, a selfie, all with terrible composition and heinous filters. Some photos I’ve deleted, even for the minor offense of having a somewhat embarrassing caption.

I had a blog I started when I was a teenager that contained mostly rants about school or my job. Some people told me it was funny. That was encouraging. One of my friends said it was “overreaching,” and I thought that was dick thing to say. Reading it back a couple years ago, I found well after the fact she was right. I paid money to access the service’s mass-editing features so I could set the whole thing to private. Now I have a Tumblr, and a Twitter, but even paging too far back there is too much to bear. I really should do something about them.

According to every think piece about the Internet and social networks, my online self is my curated best self. This was me, really trying. The ability to disappear that try-hard completely is so tempting, but I can’t get rid of everything; it’s too suspicious. I’m always going to be comparatively young and dumb on the Internet, somewhere.

It’s easy to mortify myself with all these accessible online artifacts of who I was and things I thought were hilarious or clever. Now I know better than to be that person and say or do that stuff. The stuff I’m doing or saying now: it’s fine. I’ve benefited so richly from realizing how naive I was in the past, and all of the Content I’m making reflects it. Or I think I know better, until I age another year or two or five or ten and realize that everything I’m doing now, including this, is self-indulgent and obvious.

Good thing I can be full enough of myself right now to actually think this is a good idea. This version of me I do like will exist for a little while, before it withers and crumples with time into something I don’t even want to acknowledge. Unlike my memories of myself, or the memories of people who know me, stored in our unreliable brains, my dumb tweets will not get rosier with time. That is, unless I learn to forgive my youthful stupidity, even when it’s unarguable and objective, under the fluorescent lights of the Internet.

Never Better, a collection of essays from writers we love, is The Awl’s goodbye to 2014.

Cyberfairy Magic

by Maud Newton

I’m writing a book on deadline and keeping my job, so most of my day goes to work of one kind or another. Often I tell myself that I can’t spare the time to meet friends for dinner, or to go to a museum or a party or reading. Sometimes I even call in to therapy. And yet, on occasion, on those very same days I’m supposedly too busy to go out, I spend several hours clicking around to random stuff online. “It would be one thing,” I was telling my husband a couple months ago, “if I got to the end of the day and thought, well, I squandered every free second I had on the Internet today, but at least I had a really great time!” I remember when I did feel this way, more than a decade ago, when I was first blogging, but I never do now. I think about how much nicer it would have been to go out and talk to someone.

I rely on a social media blocker called Antisocial to get my writing done. Calling it a social media blocker is misleading, actually, because although the app comes preprogrammed with some obvious culprits like Twitter and Facebook, it allows the user to add any distracting site to the list of banned places. Over time my collection has grown to include nearly any website I visit routinely for any purpose, including newspapers, my bank, the New York Public Library, and this very website. I leave my email free, a window out.

One Saturday morning last month, I woke, abluted, made coffee, and set the app to block for eight hours — the maximum. A window popped up, saying “Antisocial wants to make changes.” I typed in my password, pressed enter, and started working in my document, and the window popped up again. Again I typed in my password. Again the window disappeared briefly, only to reappear. This happened twenty or thirty more times, and then I did a forced shutdown. When I turned on the computer once more, the sites were blocked.

Through the day and into the night I wrote. The sites were still inaccessible when I went to bed, and again when I got up in the morning. For for the next day, and then two days and three, I dreaded the moment that they would become available to me again. From my phone, I checked Twitter, looked at Instagram, paid some bills. On my iPad, iPad I caught up on the news and read a couple articles someone sent me. But on my computer, I wrote, and not much else. I kept the mobile devices in the next room.

Soon a week had passed, then ten days. There were sites I needed to be able to access for my book project, sites that don’t really work on mobile devices. My pet food order was late, and I hadn’t checked on my library queue. Still, I felt like a character in a fairy tale; I didn’t want to dispel the magic of the cyberfairies.

I’m not sure exactly how many weeks passed in this way, but finally, several days ago, I really did have to do some research on my laptop, so I emailed the app’s developer. He explained that they’d sent out a message I must have missed, a warning that the app wasn’t compatible with the operating system I’d recently installed. They’d updated the app since then. In his message were links to two apps, one to clear the existing blocks, and one to update Antisocial. I ran the first, so I can once again go anywhere I want on the Internet.

But I haven’t been able to bring myself to run the second. Instead, I keep compiling and amending a long list of sites from which I’d like to ban myself forever. I’m not sure the Internet will ever seem more full of possibility than it does to me at this moment.

Never Better, a collection of essays from writers we love, is The Awl’s goodbye to 2014.

Photo by Martin Eckert.