Vows

by Haley Mlotek

A photo posted by @haleymlotek on Dec 12, 2014 at 5:21am PST

There are certain truths about marriage that we hold to be self-evident: that we should be married at all is probably first. That marriage is sacred is another. Marriage as a precursor to adulthood, marriage as a reward for a relationship well done, marriage as a contract with no clauses. On the other side are the myths forged in sitcoms with laugh tracks: that marriage is a tax citizens must pay, for a relationship past a certain threshold, a burden, a grip around your neck that you can never break free of.

I got married recently. Like, last week. There were certain practical factors at stake — extenuating circumstances that forced my hand, which has been consistently holding a do-not-ever-get-married draw of cards since I was about, mm, let’s say four years old, the age when I started actively plotting my escape from childhood. I’m not so heartless that I didn’t want to meet someone to share a life with, or so cynical that I didn’t think a lifelong partner was an obtainable goal. I was just, let’s say, profoundly uninterested in the concept of, first, weddings, and secondly, marriage. There’s a certain amount of posturing here — I’m not like a regular bride, I’m a cool bride — but I swear I hate all community-based social traditions equally. Nobody thinks it’s weird when you have an aversion to funerals or circumcisions, because those things are uniformly terrible. Weddings are, allegedly, fun! Magical! Transformative! No. I’ve been to some wonderful and beautiful weddings, and they’ve done nothing to assuage my unease, but nothing to increase my comfort level.

Because I, Haley Mlotek, am consistently Never Better™. I am fine! I’m great! Everything is wonderful! In 2014 my highs were the highest they’ve ever been and the lows the lowest — so low, in fact, that I caved and sought the help of a highly recommended psychologist following a five-week spell of daily weeping, thinking she could help me gain some perspective on my life and restore me to the kind of person who could simply take a deep breath and move on to the next thing without a hysterical phone call, a shattered glass, a screaming match. Upon hearing I was a writer and editor, she suggested that I turn these feelings into “blog articles.” In fact, she suggested after recommending I take Vitamin D and B5, that I should probably write about the way the mainstream medical profession doesn’t recognize adrenal fatigue as a real issue. This was not the therapeutic perspective I had been hoping for.

These highs and lows were metered out professionally: the end of one job, the beginning of another. They were, fittingly, parallel to my literal highs and lows; this year I flew more than I ever have in my entire life, averaging a trip to New York about once a month, the worst kind of punishment for a person who has a paralyzing attachment to routine and consistency (me) and a person who has a totally reasonable fear of flying (also me). If you are my seat mate on a flight, you would never know I’m a bad flier — Never Better, remember? It’s just that flying is — undeniably — a stupid thing to do. It’s the ultimate in relinquishing control, because, sure, there are air masks and emergency exits, but if that plane wants to plummet a billion feet to the ground, it will, and there’s nothing you can do about it, not even cross your fingers during take off and landing, not even sit as still and silently as possible, not even repeat the one prayer you’ve ever sincerely prayed in your entire life.

Airplanes are the one place I tolerate the thought that, perhaps, the to-do list I’ve set for the day, the week, the year, the lifetime, may not come to pass. Perhaps I won’t touch down safely; perhaps I’ll never write that blog article my therapist suggested, email another writer; perhaps I’ll never achieve the goals I’ve privately set for myself and my publication. Those ninety minutes are, despite the heart palpitations, peaceful; a safe landing is always jarring, a switch that returns me to the scheming, obsessive, driven bitch I strive to be. The to-do lists return automatically. But it’s a transition I notice: oh, I think, I’m still here. I’m never not surprised.

I was married on a Saturday and flew to New York on a Monday, and I surprised myself yet again by taking my wedding band with me. The wedding bands were a gift from my mother, who would simply not let the ceremony pass with my proposed option — Ring Pops — and took us to pick up nice gold symbols of ownership, property, and several thousand years of patriarchal oppression. I thought I would just use them for the ceremony and then stash them somewhere safe, tokens of a milestone I didn’t particularly take any pride in. But it was pretty; it was new and shiny. By wearing it on the plane, I knew I was going to turn it into a talisman, the way I can never fly a plane without my favourite pair of earrings — that, worse than participating in a tradition I don’t particularly care for, I was adding more weight to an endless list of superstitious crutches.

But fuck it. That might have as well have been my wedding vows. “Sure.” You might surmise that my digression into my latent fear of flying signifies a metaphor on the horizon, and you are right, but luckily for you I’m not going to compare my wedding to takeoff. Because that’s what I hate about the traditional ideas of weddings, of matrimony: I hate the idea of a fresh start, a new beginning. Even the phrase — “newlyweds” — is repugnant. I’ve been with my partner for twelve years. We’ve known each other for the only years that matter; we saw our siblings grow up and our parents’ marriages fall apart. I’ve cycled through at least three hair colours and numerous cuts and he has enough incriminating photos of me to ensure I’ll never be able to run for any political office, the hallmark of real trust. I have a tattoo of something he drew for me. There is nothing about our marriage that signifies the start of something we hadn’t already started a long, long, long time ago. If we were to indulge this metaphor, and try to compare a relationship of this nature to a flight, our liftoff already happened and I have absolutely no idea when. When did we make the conscious decision to entangle ourselves so deeply that we will never get away from each other? There have been moments — many moments, in fact — that I could point to and say that was it, that’s takeoff, but none of them are entirely it. Or maybe all of them are entirely it. Some of them are really, really funny, in the way that only teenagers can laugh at; some of them are really, really real, and their memory provokes the kind of shortened exhalation only adults with undiagnosed and untreated anxiety issues will recognize. I will not be describing any of them.

Within marriage, it’s the cruising that scares me. That’s the metaphor I’m working with. The idea of a perpetually even ride with no landing in sight. Never Better™ — a rallying cry of your continued success, sure, but also a kind of perpetual equilibrium. My fear of marriage, before getting married, was that it was a way of telling the rest of the world that you were done. Your flight had settling to a healthy cruising altitude and only devastating destruction could bring it down ahead of schedule. No more ups, more downs, no more of that kind of terrifying and exhilarating frenetic energy a new sexual partner brings, no more of the kind of exhausting and crushing depression you can only get from romantic rejection. You’ve stood up in front of your family and your friends and your God — lol jk — and pledged that you would keep still, keep on schedule, keep yourself at best and never better.

“This is the shortest ceremony I’ve ever performed,” our judge joked on that Saturday, referencing the vows I had slashed to the barest minimum, refusing to pledge obedience and fidelity, only allowing a boilerplate version of your basic wedding ritual to appease the traditionalists in attendance. The vows I was most interested in had nothing to do with obedience, something I have never and will never be; they had nothing to do with monogamy, a value I’ve always considered about as puritanical as cutting carbs (great if it works for you, but ultimately morally neutral).

Our marriage will be, I vowed, a talisman, a promise, another weighted object to add to a pile of superstitions and other prayers, something that is better than sacred or solid, something I believe in and participate in despite knowing better, despite evidence to the contrary, despite my best intentions. My marriage will never be greater than the sum of the parts we’ve already put together. It will never be better than the relationship we already have. But I am, I solemnly swear, allowing myself to count on a safe landing.

Never Better, a collection of essays from writers we love, is The Awl’s goodbye to 2014.

This House

This house I will leave in 2014. This house on this street. This house which was built, as far as I can tell, in 1863 or 1865. This house which is twelve feet wide and three stories high. This house which is crooked and creaking and which I have inhabited since 2010. This house which I love. This house, the first house which was actually mine. This house in this Brooklyn, this Greenpoint. This house which is mine but not for much longer, sold almost now to new people. I see them here, almost. Add their names to the list.

And I do have a list. I know the names of every owner of this house back to the first one. There are six, including us. A short list, considering the age. I know what they do, and before that, what they did, because many of them are dead. I couldn’t live in a house without looking in the closets and prying up loose boards, without checking out the previous occupants. I am looking for layers beneath layers. I am more interested in the earlier occupants than in the recent ones. I try to give the living their privacy. That doesn’t stop me from contacting them. Occasional emails, questions. “When did this change? When was that done? Do you think that window was always there?” I wonder what they make of all that. All my questions.

I am interested in the house as a Being on Earth. I seek out old photos of this house. I have tax photos of this house from 1940 and 1980. I have photos of this street and this block from 1910 and 1921. “That tree wasn’t there in 1910,” I say to my husband. He’s somewhat uninterested. He doesn’t look backward, only forward: to the next house.

This house, unlike many others in Greenpoint, isn’t a stately brownstone built for the rich shipmakers of the late nineteenth century. It is not made of brownstone, or of brick, but timber. Its exterior is ugly white siding; its interior is so lovely. I have seen the rafters above the ceiling of the third floor. They are magnificent: huge, and terrifying. So old, but still holding the whole thing together. Just twelve inches from the ceiling where I sleep. They keep our secrets, and the secrets of our five owners before. Dear rafters, I love you.

This house, unlike many others in Greenpoint, isn’t a multi-family affair. It was built, against the odds, for a single middle-class family, in the eighteen sixties. Just twelve-feet wide. Just thirteen hundred square feet — an apartment in many other cities, but a palace in this city. A yard. A tree. A basement. A life. A family can grow here, in this house. It did; it does.

This house saw the Civil War. This house witnessed World War I and it stood here, with all the other houses, through World War II. This house has had its shares of ups and downs. This house knows.

Greenpoint used to be an orchard, just here.

The next house, the house for 2015, is much newer: It was built in 1949. The New House is arguably much more interesting than the old house. It is nestled among rocks and trees, and there is a ravine and a forest behind it. I know the name of the man who built it. Who planned it. Who loved it and who first inhabited it, too. Some of them still live. I email them, too. They are special people to me: the builder, the architect, the first family. We are going to be friends.

I haven’t fully moved on yet, though. I’m still living in This House. It’s still 2014. I still love this house. I love Annie, the Irish immigrant, the widow, the mother of eight who built this house for her family. I love her and I love this house’s power. I look under the floorboards for traces of them but I should have known where the most likely places are to find what I am looking for.

In the basement. The terrifying, low-ceilinged basement.

The man who comes to fix the boiler says to me, “Here’s the hearth.” “What?” I ask, intent on a solution to my heating problems, not just then peering about for history. I look to the ground, a slightly raised pile of dirt and debris is all I see. “The flooring above, it’s really uneven,” I say.

“You can’t fix that. It’s just this house,” he says. “it will always be this way, because the hearth was here. They used to put the coal in here to feed the fires above. Do you see?”

The bumps in the floor, because the hearth is just beneath. The indentations in the plaster for fireplaces where fireplaces haven’t been in sixty-five years. The bathroom which never should have been. I see it. I see the landscape, and it’s a city not the country. I see the layers of siding upon siding, but also thick timber when the man who cuts a hole deep, all the way through the house for a vent and shows me what he has found. A circle of wood, three inches deep, with layers upon layers of life. A tree’s rings, but for a house. We’ve added some of our own rings, too.

When we rip out the kitchen counters in late fall of 2013, not knowing that we’ll be leaving so soon, we find underneath the sink, a treasure, for me: in thick black marker, a heart. “Julie and Kerry.” I take a photo of it. I send it to Julie. “Look what I found,” I say.

Yes, our house. Our house which I will leave.

When we came here, when we bought this house, we were left things: keys, manuals to appliances, a broom and a shed. But also, a photo in an envelope. Inside, that first day we walked into the house, empty, quiet and dark, I pulled the photo from the envelope.

It was the house in 1940. A tax photo. The siding was different but only marginally more ugly. The tree was smaller, just slightly in the photo, but also out of view. My future then, but soon to be my past.

When I leave this house, I will leave behind my traces. I will leave you, new owners, the photos, but also my paint colors and my dreams. My hopes.

I am in the New House. I look in the cupboards. There is a linoleum tile here. It is “original.” “What is this?” I ask, only to Zelda, my daughter, who is strapped to my chest. Anyone else would say, “Get rid of this, it is ugly and chipped old linoleum tile.” It is, I agree. It must go. But for a moment I think about keeping it. Suffering through its ugliness in favor of preserving the past. 2015 will not have chipped asbestos tiling. I find an old key. I put it my pocket before we go home to this house.

2015 will be new for owner number seven of this house, and for us, too. To the future.

Goodbye house.

Never Better, a collection of essays from writers we love, is The Awl’s goodbye to 2014.

New York City, December 28, 2014

★★ The otherwise dull gray morning sky briefly developed, in the east, shining metallic patches, which reflected in the mirrored building to the west. In early afternoon, some wan sunlight made it through. The clouds were more interesting when one was out under them; overhead, some of the dimples in them went clear through to blue. Puddles lay in the gutters and at the seams of things. There was no need to fuss with zippers or hats. For a little while, out the windows beside the swimming pool, the clouds pulled apart into white. Then they closed over, duller than before. After sundown, though, the thin parts of the gray acquired a bright blue glow, like a remnant of some nicer day than the one just ended.

A Tiny Crisis

by Brendan O’Connor

About a quarter of the way through Kerry Howley’s Thrown, a book of reported non-fiction about semi-professional mixed martial arts fighters in the Midwest, the narrator reveals herself to be not Kerry Howley, but Kerry Howley’s stand-in, Kit, who is like Kerry Howley, but not quite — or perhaps more so. “My (admittedly neurotic) progenitor,” Kit tells us, “is so conscious of her own tendency towards self-confabulation that she hesitates to call anything she says of herself a fact. She has never known a real person who saw herself with even passable clarity; never known a storyteller who could tell of a trip to the supermarket without self-gratifying sins of omissions. All narrators, I say, are fiction. All. The reliable ones have the decency to admit it.”

We are given to understand that the things recounted in Thrown are true things that did happen to real people, that they are not fabrications, and that it is only the person who is recounting them who does not exist in the physical world. Kit, the narrator, is Howley’s avatar in the world of the story; Howley is giving herself the same treatment that all people who are written about inevitably get, of being reduced to their most representative parts, despite — hopefully — our best intentions and efforts, as writers to render them whole. They become characters. Often they become characters before they even make it onto the page. At our least generous, the people we write about are, to us, never anything else.

It’s a truism of literary criticism that the narrator and the author are not the same person. In fiction or poetry or things written about fiction or poetry — which is what I read pretty much exclusively until about two years ago — the distinction between narrator and author, while useful, is sort of obvious. But writing non-fiction, I am not so cognizant — or at least not always — of the existence of a narrator, someone that lies between me, the writer, and you, the reader. Maybe I should be. In some stories, this narrator is more prominent than others. “Put more of yourself into this,” an editor might say. Or “I could really hear your voice in this piece,” a former teacher might say. And in something like this piece, whatever it is, who is here, in these words, speaking to you, the reader.

Anyway, I think I’m having a crisis of faith in the notion that so long as I do my best work and am present and accountable and responsible (or at least try to be) that it will all work out. Why should it? It’s not like there is a specific goal towards which I am working. People ask what my dream job would be and I tell them, “Staff writer at a fancy magazine,” and laugh and laugh because who knows if fancy magazines will even be around by the time I’m a good enough writer and reporter — a potentiality which is of course itself strictly theoretical — to even consider trying to convince one to pay me a salary to write the weird things I write.

As I take stock of where I am and where I have been and what I have done in the last twelve months, even as I see so much progress, the part of me that holds all my self-doubt and self-recrimination and self-loathing creaks open and all these horrible little grasping creatures crawl out. They look familiar, if a little pale from lack of sun, because the truth of ambition is that it is always shadowed by resentment, as hope is by regret.

We can only control so much, and everyone is just figuring it out as they go along. Still, it’d be nice to have some clarity about where I’m going. I might adjust accordingly, if only to get there a little faster.

Photo by xiaozhen

Never Better, a collection of essays from writers we love, is The Awl’s goodbye to 2014.

What I'm Looking Forward To In 2015

I spent more time than was sensible in 2014 waiting for the asteroid. At night, in the dark, unable to sleep, I’d work over every event that was wearing me down, from my own petty problems to the seemingly intractable issues facing the city, the country, the planet, until, unable to find a way out of worry, I would surrender to the comfortable certainty that somewhere out there in space was a giant piece of rock hurtling undetected toward Earth which would suddenly slam into us and put an end to everything. If there were enough time for a further wave of evolution to do its thing before the sun finally closed the books on this solar system, maybe whatever came after would have a better chance of making the world work than I managed to (it all being about me, obviously), but that wouldn’t be my problem one way or the other. It’s an impossibly immature fantasy — everything ends without anyone even having to panic or prepare; no need for reckoning or repentance — but it is not completely impossible, and that tiny thread of plausibility is what I would cling to as I finally managed to drift off.

The book of the year was pretty clearly the English translation of Thomas Piketty’s Capital in the Twenty-First Century. Forget fiction: No one has anything worthwhile to say anymore and even if they did the current custom of churning out memoir-ready observations about life rendered in flat, affectless prose — as if its very lack of adornment weren’t some sort of obvious, in-plain-sight disguise for its essential emptiness — would induce rage if it hadn’t first produced an stultifying sense of exhaustion. No, Piketty’s examination of income inequality and the tendency of power to entrench and extend itself down through the generations was the manual of the moment, and in spite of my deep pessimism concerning our ability to actually make things better for anyone, let alone everyone, I have to admit a small feeling a joy when I think of how many coffee tables, however briefly, hosted this giant slab of capitalist critique. One has to imagine that the poor wretches who work the Amazon factory floor were less entranced each time they scurried up the ladder and lifted down those massive tomes so that another member of the fraternity of man could express his solidarity at 30% off list price plus “free” two-day shipping, but that is surely a detail too churlish to concern oneself with.

Still, as heartening as it was to see the discussion shift even just a little bit in the direction of fairness, I had to laugh each time I heard a central tenet of Piketty’s thesis — that the postwar rise of the middle class was a mere historical anomaly — asserted. As if it all weren’t a historical anomaly. As if we weren’t, in the scale of geologic time, just a small sliver away from sleeping in trees to avoid being eaten by the fierce beasts that roamed below. As if we weren’t smack in between the arrival of the giant asteroid that killed off the dinosaurs and the arrival of the next giant asteroid so clearly overdue.

The movie of the year was pretty clearly Nick Cassavetes’ The Other Woman. I should perhaps qualify this by saying that I am in no way the person who should be judging the movie of this or any other year since I am no longer able to spend any time watching a movie, both because of a tragically truncated attention span and the growing conviction that spending two hours in a dark room watching adults play pretend is an inexcusable waste of time (and this comes from someone who will suddenly realize he has spent three hours following the Wikipedia trail of 1970s sitcom stars all the way down to the stubs and write it off as just the cost of having the freedom to open another tab). So I did not see Nick Cassavetes’ The Other Woman (or, for that matter, any other film) this year, but I was unable to avoid its promotional poster, on which the actress Cameron Diaz finds herself wrapped up by her co-stars Leslie Mann and Kate Upton. (Presumably at least one of these three is the titular woman; perhaps they all are. Perhaps the movie is an in-depth examination of the otherness we each occupy at some point; again, I cannot say.) What I found so striking about this image, what stuck with me so strongly that I am here declaring its affiliated product the movie of the year, a work of art that stands as the emblem of its era, is the look on Diaz’s face: She evinces the bemusement borne of the fatigue that comes with existence. It contains sorrow, resignation and perhaps a small amount of recognition of just how absurd our condition is. (Later in the year I saw a still photograph from the Jake Kasdan feature Sex Tape in which Diaz wears an almost identical expression, which may indicate that this is simply one of the basic looks her face makes, but by that point I had spent too much time in my own head developing this theory to abandon it because of the actress’ range, so we’re just going to proceed as if that part never happened.) I resolved to somehow adopt this aspect of her appearance and make it the center of my own emotional register: Sure, everything may be terrible and only getting worse, but what are you going to do? You might as well acknowledge the amusement of the cosmic ridiculousness that provides the background music to which we all go about our business as we wait for our asteroid to come.

But are things really getting worse? I have seen, especially recently, some positive and optimistic assertions that things are not as terrible as they appear and that perhaps the sense of mounting chaos we all seem to feel these days is merely an expression of ego, of an inability to appreciate a more broad historical perspective. This is undoubtedly an admirable view. As someone who believes that the most successful people in our society are those who can completely discard the crippling awareness of how horrible and meaningless almost everything is, those who can actually convince themselves that the things they do are of value to civilization and merit the massive amounts of money and attention (the major metrics by which we keep score) they receive, I can certainly see the upside to being upbeat. If, to choose a random example, the massive amount of self-delusion required to think of yourself as someone who is shattering the paradigm of transportation by providing more opportunities for the well-off to be ferried about by those who are being left so much further behind than previous generations of able-bodied individuals that their only value to the labor pool is as cut-rate chauffeurs is what it takes to get yourself generally acknowledged as the disrupter of the year then certainly the considerably smaller level of wishing it so required to believe that things aren’t getting worse is nothing to begrudge those who don’t want to face the fact that we have already been to the place where it is as good as it’s going to get and not only wasn’t it all that good to begin with, it’s gonna get a whole lot worse before it all ends. And maybe I’m wrong. It happens every day, many times each day, sometimes simultaneous to the very announcement of my most recent important observations. As a fair-minded individual aware of his own frequent fallibility I will not rule out the idea that maybe things are actually getting better. Maybe we aren’t just a bunch of jumped-up monkeys who wander about in a state of want, shuffling around inexorably under the direction of chemicals controlling our every move while we come up with post-facto rationalizations for why our own behavior is justified but everyone else’s is so selfish and inexcusable. Maybe we aren’t simply accidents of time and space but beautiful beings created by a higher power who struggle and stumble but eventually travel in the direction of a transcendent grace which we can’t yet imagine but will someday achieve. It’s possible, I guess. But the more consideration I give it the more I am left with the one simple question that I think best expresses my own hopes and dreams for the future: Where the fuck is my asteroid already? I am anxious, but in my own way optimistic. Surely it will come along soon enough.

Never Better, a collection of essays from writers we love, is The Awl’s goodbye to 2014.

A Rapper for Zion

by Alex Cocotas

On the evening of July 12th, a few hundred activists gathered in front of the national theater in Tel Aviv’s Habima Square to protest against the ongoing military operation in Gaza. They carried signs that said things like, “End the occupation,” “Stop the slaughter in Gaza,” “IDF [Israeli Defense Forces]: the most ethical terror organization in the world,” and “We do not want a government of inciters.” Shortly after the protest started, a few counter-demonstrators arrived to shout down the protesters. Over the course of an hour, their number rose. Most were young men with close-cropped hair or shaved heads; some appeared not yet out of high school. Many carried Israeli flags, and a seemingly inexhaustible list of insults. They sang the national anthem, called protestors “terrorists” and “traitors,” and chanted, “The nation demands that leftists be expelled.” A few wore t-shirts with a neo-Nazi symbol.

Habima Square lies at the end of Tel Aviv’s most posh street, Rothschild Boulevard, a picturesque, tree-lined route dotted with crumbling Bauhaus buildings. At most protests, demonstrators and counter-demonstrators face off where it turns into a T-shaped intersection in front of the square — one group on Rothschild, the other in the plaza. On this night, however, the police did not enforce the prevailing division; both sides were inside the square, with only a single, permeable row of officers between them. As tensions mounted, police did little to defuse the situation, even as some counter-demonstrators began trying to physically assault the anti-war activists.

One of the counter-demonstrators was a large man covered in tattoos named Yoav Eliassi. He stood a few feet behind the police line, bobbing his head under a baseball hat and intermittently checking his phone. Earlier that day, Eliassi had written on his Facebook, “Today at 8:00 in Habima Square, we are representing the IDF that is protecting us, across from the ungrateful and disrespectful left that in the time of war dares to protest for our enemies and against the IDF, so leave Facebook for the moment and come to show that we are not suckers.” In the comments, people responded to the call and told him they were on their way. Later, he posted a video with the comment, “Currently waging war in Habima Square for the dignity of the country and the IDF. We are 80 across from 500.”

That same day, Hamas had publicly promised an unprecedented bombardment of Tel Aviv at 9 p.m. “As nine o’clock approached we began thinking about what would happen if [they] realized their warning,” wrote the Israeli journalist Haggai Matar, who participated in the protest. A little more than an hour after the protest’s start, two sets of sirens rang out, swathing the city in their stifling moans, driving most of the police toward bomb shelters. Interceptions from the Iron Dome missile defense system boomed above the city. One interception, directly over the square, lit the night sky with an orange burst, causing everyone to pause long enough to gaze at the sky until the distorted ghost of ash and smoke vanished.

After the sirens ended, it was agreed that the peace activists would leave under a protective cordon from the cops, but a group of counter-demonstrators snuck around the police line and attacked the fleeing protestors. Before the police could reestablish order, numerous activists were assaulted; one had a chair smashed over his head, and others were chased into cafes to seek refuge.

Eliassi took to his Facebook once again: “Thank you to all who came. We started with three across from 800 and we finished with 350 across from zero of theirs. It was crazy to do all this with the sirens in the background and explosions in the sky, but we did not move and stood our ground until the end. The police representative (who, by the way, treated us great and we saw the pride on the faces of the special forces and the restraint toward our side) took me aside and wanted to see these lions of the Shadow –and thus he gave a name to the group I’m organizing, which is essentially all of you…Together we are a force against the real enemies that walk among us, the radical left, and thank you to my friends that are apparently called the lions, and thank you very much to the IDF all this is for you!!”

Eliassi is better known as The Shadow, a once-ascendant Zionist rapper who had largely faded from public consciousness over the past decade, and his second act as a right-wing street organizer and demagogue was just beginning.

Hip hop first came to Israel in the nineties. In contrast to its American progenitor, Israeli hip hop was notable for primarily vocalizing the views of mainstream culture, and it eventually coalesced around the thematic pillars of Zionism and national identity. There was a subtle undercurrent to this development: By focusing on Zionism and Israeli identity, which historically draw their strength from existential threats amid a hostile world, Israeli rappers could recast themselves as marginal figures and assume the outsider status that hip hop’s origins seemed to demand. They, in effect, reconfigured the mainstream under the guise of a marginal voice.

The most vocal proponent of this style of “Zionist rap”was Kobe Shimoni, known as Subliminal, who would go on to become Israel’s most famous and influential rapper. It was Shimoni who convinced Eliassi, a long-time friend, to pursue a music career after failing to land his dream job as a cop; Shimoni became the lead man in an emerging tandem act with Eliassi, falling somewhere between hype man, fearsome presence, and semi-permanent guest star. Their music was tinged with nationalist sentiment from the start — partly a reaction to the perceived paucity of national pride among popular musicians, but it was also heavily indebted to the style, wordplay, bravado, and violent imagery of American gangster rap.

They first gained wider recognition with the release of Shimoni’s 2000 album, “The Light from Zion,” which featured Eliassi on several songs, most prominently the hit “Living From Day to Day.” It caused a minor uproar in the press — one headline read: “Ku Klux Klan: I’m Terrified of Subliminal’s Racist Hate Music” — although most the lyrics are fairly mild, especially compared to some contemporary rhetoric. More important, however, was the album’s timing: The collapse of much-hyped peace talks that same year was swiftly succeeded by the Second Intifada, largely synonymous with the subsequent wave of suicide bombings in Israeli memory. In an atmosphere increasingly permeated by fear and distrust, Shimoni and Eliassi’s unapologetic nationalism struck a chord with listeners.

As the security situation deteriorated, Shimoni and Eliassi became increasingly devoted to creating their aggressive brand of Zionist rap. “Making music is fine,” Shimoni said at the time, “But I always said that I use music as a means. My goal is to relay a message.” Their next album, the 2002 combined effort, “The Light and the Shadow,” made them household names, selling over a hundred thousand albums in a country of eight million people. On one song, “Biladi,” the chorus, sung in Arabic, is “This is my land / This is my country,” a clearly formulated middle finger to Palestinians. When asked why it was in Arabic, Shimoni answered, “Because the people who are supposed to understand it understand Arabic,” although Subliminal less-than-convincingly asserted that he is a “Jew that respects Islam.”

The album’s success changed Eliassi’s life. As a child, his family’s finances were chronically unstable. His dad frequently turned to scams to make money — Eliassi once woke to find a cop searching a closet for his fugitive father. After the start of Eliassi’s mandatory three-year military service, his father, who had just survived a murder attempt, was convicted of fraud and the family sank deeply into poverty; Eliassi resorted to stealing from the army to help keep food on the table. Now, for the first time in his life, he had money. He lived in penthouse apartments, spent hundreds of thousands of dollars on cars, drank heavily and harbored a burgeoning sex addiction. He later told NRG, “If I did not [have sex] with four women a night in the bathroom of the club, I could not return home.”

Shimoni and Eliassi maintained a relentless touring schedule at the height of their popularity — roughly the first half of the decade — criss-crossing the country to play smaller communities otherwise ignored by the cultural establishment, furnishing their act with something of a populist feel and making them an instantly recognizable presence to much of the population. For many, their music embodied the anger, anxiety, and latent isolation that pervaded as violence enveloped the country amid an ever-louder echo of criticism from abroad.

But interest in aggressive, hyper-nationalist music began to wane as the security situation stabilized and the Second Intifada faded. Eliassi’s long-awaited solo album, “Don’t Give A Fuck,” wasn’t released until 2008 and relatively few fucks were given by the listening public. Declining sales and extravagant spending habits led to financial problems; in March of 2011, he was declared bankrupt. As his output declined, Eliassi became a source of gossip fodder, known as much for trying to smuggle his Chihuahua into restaurants as for his music. Whatever his frequent complaints about the media, continued press coverage seemed a matter of some existential bearing, “The moment that they stop writing about me in the gossip section, I simply will not be there anymore. As long as they are writing about me, it means that everything is ok for better or worse….If [someone] is not in the gossip section, this means that he is not worthy of gossip and this means that this person does not exist.”

After a protracted spell of being below radar, a video of Eliassi arguing carnivore rights with vegan activist Tal Gilboa — who, incidentally, just won Israel’s most recent season of Big Brother — went viral on Facebook earlier this year. The experience was instructive. In a recent interview [Hebrew], Eliassi said it was the first time he realized the power of Facebook. In June, after three Israeli teenagers were kidnapped, and subsequently found murdered, his statuses pushed for a greater military response and he took part in the government-sponsored #bringbackourboys campaign — adding his own tagline: or we’re coming for yours. He described the discovery of their bodies as very difficult for him, and again called for greater retribution on Facebook. Most memorably, he posted a picture of himself, since removed, holding a photoshopped pair of testicles while affecting a solemn mien, which said, in red, “revenge,” and in white, “BB [Netanyahu’s nickname]. I think you forgot these!!”

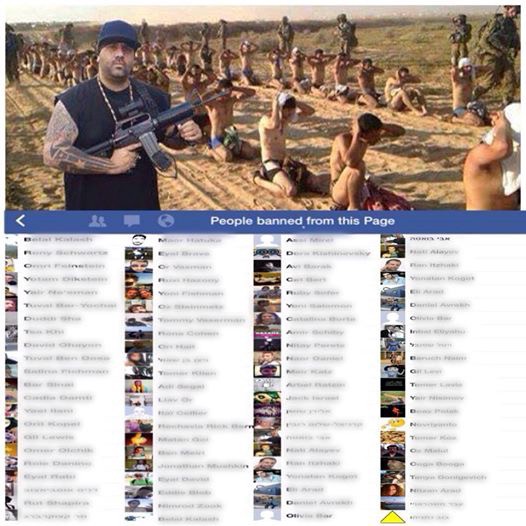

After the July 12th protest, Eliassi’s name dashed across the country’s major media hubs for the first time in years, quickly becoming the face of some vaguely defined phenomenon, characterized by an unprecedented cascade of pressure on the conflict’s few public dissenters. Three days after the protest, he rolled out a Facebook page for his new organization, “The Shadow’s Lions.” The lion, he later clarified, is a symbol of Israeli unity, his organizational aspiration. (Though in one post, Eliassi called it a “Zionist army.”) The page had more than thirteen thousand followers until it recently disappeared without warning. Eliassi’s personal fan page, which seems to have been dormant for a year (and sparsely used before that), was re-activated and became his central communication hub, gathering more than forty-nine thousand followers over the past four months. It quickly became something of a one-man media center, a place where Eliassi could muse about war developments, spew vitriol at rivals, inflame followers with perceived injustices, or wax maudlin about his fate as the conveyer of these truths. A cursory scan of his page indicates the majority of his fans seem to be young men (and Facebook confirms that between eighteen and twenty-four years old is the most popular age group of his followers). (Eliassi did not accede to an interview request, but said I could send him a list of questions, which he has so far ignored).

Tens of thousands of followers might seem insignificant, but relative scales matter. The total population of Israel is over eight million. Over 5.2 million are non-ultra-orthodox Jews, who form the bulk of Hebrew-speaking Facebook. To draw an unfair but nonetheless instructive comparison, a similar proportion of likes in the United States would be over two million followers. Eliassi’s following, additionally, is comparable to influential political figures: Zehava Galon, head of the largest left-wing party, Meretz, has sixty-four thousand followers; Isaac Herzog, head of the center-left Labor party, has forty-seven thousand.

Eliassi has become a target of criticism in the months that followed, mostly from the left. Internet memes dressed him up as a Nazi. The Minister of Education, from the center-right Yesh Atid party, accused him of “polluting the souls of Israeli children,” tapping a collective anxiety about the growth of extremism among Israeli youth — a fear compounded after virulently anti-Arab protests in Jerusalem last summer were rife with visibly underage participants. Eliassi’s oft-posted portraits with smiling soldiers certainly did not alleviate anxieties, either. However, he strenuously denied any involvement in the violence, insisting it took place after he left the protest and was no longer involved.

Although Eliassi has faced some hostile questioning in the press, the public has been sympathetic on his central issue: The attitude towards anti-war protestors is almost uniformly negative. A common sentiment, which I heard personally on several occasions, and versions of which could be found in the media, from passing hecklers at protests, to in the infamously toxic “talkbacks” under news articles, was: “Yeah, I know, democracy, but… not while there is a war.” While some mainstream Israelis indubitably found Eliassi to be ridiculous, the logic of the atmosphere dictated that he had to be accommodated, lest questions of one’s own sympathies come under suspicion; supporting the troops, even as vague declamation, was an unassailable position, not so easily excised from the public discourse. This, perversely, probably served to increase his audience: The number of counter-demonstrators at anti-war protests swelled in the weeks the July 12th demonstration. Eliassi said at the time, “I feel that I became a leader without intending to. Decision makers from the right turn to me in order to receive suggestions from me. I entered a restaurant yesterday and everyone was standing on their feet and chanting for me.” More recently, the country’s largest newspaper ran a long, largely sympathetic interview with Eliassi in their weekend edition, running to almost five thousand words.

Eliassi’s re-found prominence following the protests and media coverage has not translated into a coherent strategy for his organization, which appears haphazardly strung together without little sense of direction; it is unclear what Eliassi ultimately hopes to achieve. Eliassi or his group have also posted pictures of people, perceived political enemies, on their Facebook pages along with their name and offending quote or action. Sometimes the target was prominent, such as a video of them yelling at left-wing columnist Gideon Levy (eleven thousand likes), but more often it was a seemingly random person who’s Facebook post had somehow found its way into their hands. Palestinian citizens of Israel seemed to be singled out for special treatment. Some of these people reportedly lost their jobs.

Many critics point to Eliassi’s re-emergence as a shameless attempt to restart his music career. Eliassi waves off these accusations as if they are self-evidently ridiculous. There is some truth to his contention: Although he has released a few songs recently, even he acknowledges that there is not much appetite for hip hop in Israel these days. However, this takes a narrow definition of what constitutes his career. If you take the “The Shadow” brand — as someone to pay attention to, listen to, or write about — as a natural extension of his career, it is inextricably weaved into the texture of his activities, which primarily seem to be announcing and organizing counter-demonstrations to planned pro-peace, anti-war, or anti-occupation protests; collecting and distributing consumer goods to soldiers stationed near Gaza during the war; and posting many, many pictures of lions and the Star of David photoshopped together.

Eliassi is ultimately only a symptom of the current atmosphere in Israel: Without a fundamental change in its prevailing political culture, he will be neither the last nor least benign of these characters to emerge — but recent developments do not portend a foundation for positive change. The resolution of the Gaza conflict in late August was inconclusive and did nothing to substantively address its underlying causes; the expectation of renewed hostilities is widespread. Near-daily protests and violence in Jerusalem have shattered the illusion of a tentative calm and some suggest it may auger a new, semi-permanent instability. The specter of international isolation, more than ever, haunts the political horizon. Part of the problem is institutional: despite weeks of protests marred by right-wing violence, more peace activists were arrested on August 2nd for trying to stage a small pro-peace demonstration than from any single incident of right-wing violence. But it also represents a societal drift, driven by a traumatic legacy of violence, economic precarity, an ideologically charged school system, and reckless political opportunism, padded out by a largely acquiescent media.

The effect of Eliassi’s campaign is to further narrow the already tapered space for public debate in Israel. Eliassi’s aspiration of national unity may echo his earlier calls to increase national pride, but it is less about nourishing your spirit at the collective well than erecting a framework for excluding voices outside of an inexact consensus. While he says everyone is entitled to their own opinion, if you care about human rights or question the army’s infallibility, you are classified as one of the “real enemies that walks among us,” compared to terrorists, and subsequently made eligible for public harassment. While not officially-sanctioned, it helps create informal barriers to speech that are intolerable for the average citizen, enforced by an implicit threat of violence. Nonetheless, shades of Eliassi’s rhetoric can be found among mainstream pundits and politicians: musings that those not “loyal” to the country should be stripped of their citizenship foreshadowed a similar move recently suggested by Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu.

On August 9th, a coalition of left-wing groups planned a large pro-peace rally in Tel Aviv. The police pulled the rally’s permit a few hours before its start, but a few hundred demonstrators turned out anyways. They were met by a group of counter-demonstrators, including Eliassi and his lions. One of the counter-demonstrators held up a sign that read, in Hebrew, “One people, one country, one leader,”an almost exact translation of the Nazi’s famous formulation, “Ein Volk, ein Reich, ein Führer.”A few days later Eliassi took to Facebook to clear up the matter. “Extremist leftists”had “infiltrated”the protest and distributed the signs to his “innocent”people who did not understand the “blatant and extreme criminal incitement of the radical left.”About a month before, Eliassi released his first song in years. It was called “One Blood.”The chorus was “One nation / One blood / Come against us? / No one / One God / One heart / You won’t walk alone with the number one army.”

Photos via Facebook

Rod

by Michelle Dean

In the middle of the year, an old professor of mine, Roderick MacDonald, died of cancer. He had been sick for some time, I’d known that. But the disease had tides. He’d tell me, or I’d hear, that he was in treatment; then he’d tell me, or I’d hear, that the treatments were over. We didn’t live in the same city, so I never saw him anymore. The coming and receding of the crises of his illness became something filtered, heard in the background, like the white noise soundtrack (“Ambient Sound Therapy: Rainy Ocean Sounds”) I use to sleep. In other words: I didn’t think about it much.

The last time I saw Rod in the flesh was about five years ago. I had just been laid off from a job I’d hated. Rod knew I hated this job. He knew because in the five years I’d been in it, I’d consulted him constantly about what else I might do. Should I clerk for a court? Should I become a theatre director? A law professor? A writer? Like a lot of people in my life who’d watched me sink into a depression during the five years spent locked in a tower of boredom and granite, he thought of the layoff as a relief. His response was jovial; he would be in New York soon, we should have a drink.

In late May, someone made a short documentary about him. A person more attuned to the world around her than I was this year would have realized what that meant. I responded to it simply as a sweet tribute. Someone had to lay it out for me that Rod was dying. I should write to him, this person told me. Rod would like that. He’d reply if I did, this person promised.

I wrote a couple of drafts. I dallied. I couldn’t figure out how to write, “I have heard this is the end, are you okay notwithstanding that big giant immovable fact of it, what can I write that would help or at least comfort you?”

I’d met Rod as a professor in law school when I took a sort of meta-class, one in which we talked about, and experimented with, how to teach the law. Rod was one of those teachers who spoke about teaching in a quasi-religious way, but he wasn’t the type who felt married to one model. In fact, he wasn’t much for Socratic style, the classic law-teaching model, at all. Does that sound weird for a law professor?

Out here in the world, I feel like I’m describing a remote island whenever I try to talk about the Faculty of Law I attended. It had law school-like qualities, but it also suffered from self-hatred about being a law school. It was a small town of existentialists; we were trained to be doubters about what the law was and what it could do. When it becomes clear to you that the law can be bent, even pretzeled, to approach a kind of justice, there’s power in that — there’s possibility.

Rod was the man who had set up most of the intellectual scaffolding that we used to explain our attitude toward the law. Many of the other professors had been students of his at one time too, so his presence at the school was pure paterfamilias. He clearly loved this role, attending the weekly beer socials pretty much without fail. There were always a circle of students who were close to him and this was viewed as a kind of prize. He had another side, though. Mercurial, complaining. This is not to speak ill of the dead; I’m not even sure I believe in that convention. It’s just to tell you the truth. I dislike the convention of memorializing teachers as secular saints, as ascetics who devoted their whole lives to service.

The one time I took a formal class with Rod, he invited us to his home for drinks to celebrate the end of a semester. After a beer or two he pulled out his guitar and began playing for us. I remember it was Phil Ochs. He implied to us that he’d known Phil, though we were too young to probe and figure out if he meant, through the music, or in person. I remember him giving some kind of melancholy speech which began, “After Phil died,” but I don’t remember the substance of it. I remember only the uncomfortable glances I exchanged with others in the room. And that we made our excuses and left soon after.

We can be forgiven our uncomfortableness, I think. We were all in our mid-twenties. The world still looked flat. To us, Rod’s life looked like a success. He was a respected professor. He had a nice house and a family. He had awards and honorary titles and prestigious memberships up the wazoo, as they say in this country. I think, actually, he would have described himself as a success when asked. Nor would he have willingly applied the term “failure” to any area of his life. Still: We were too young to see that titles can also function as cover stories, records of achievements that you repeat to soothe yourself about the other ones you didn’t manage.

Rod was in town to do some work with the United Nations so I chose the least-ridiculous east-side Midtown bar I knew of: P.J. Clarke’s. He strode in, a tall, gangly man, with a teenager’s animation well into his sixties. I remember thinking, at all of thirty years old: God, I feel so old compared to him.

I had spent the first month or so after the layoff in a daze. I’d always known I’d leave that job but it caught me short about what I would do with myself next. And of course I wanted some authority figure to tell me what to do. Rod being Rod, he had already taken charge. Within a month I had been admitted to a graduate program in law, one which would give me a much-needed year to read and think. And in the bar he let loose, without speaking to my particular situation much, about his own worry that the kind of firm I’d eventually join was destroying young minds; I had heard versions of this rant before. He kept saying, “I knew it would be a waste for you. You’ve had the experience, it’s time to move on.” He said it on the sidewalk where I hugged him for the first and last time, and thanked him, and watched him briefly as he walked up Lexington Avenue. Then I got in the subway.

I’m not a lawyer anymore. But Rod’s descent to the end came at a time when I was locked in another professional crisis. I had a job I was ill-suited for. It was the law firm all over again, in some ways. I’d wake up in the morning full of dread. I got headaches. I had writer’s block. And I wanted to send Rod a better email than these conditions could produce. I wanted to send him something that said, “Thanks for rescuing me, that time. Thanks for being a person whose voice I still hear in my head years after I was actually in your presence. Things you thought, things you did, changed me.”

But I thought in order to say that I’d also have to claim to have been a success. I’d fallen back into that old trap of believing that success was a thing I would be able to declare unconditionally. I remember actually thinking, I’ll write when I’m feeling better about where my life is headed.

What a useless little bit of self-delusion that was. Not just for being so selfish, but also for not knowing that Rod was capable of grasping a more complicated picture to me. A few days ago, I began sorting through the emails he’d sent me over the years. Although at the time each one felt ephemeral, glancing, I can piece together the way he thought of me. A good summary of it appears in a letter he once wrote to a judge about me, in which he put his finger on a major failing of my self-presentation.

In any interview with Michelle I think it important not to be misled by the manner in which she would respond to a question about a legal point. One might have the impression that she has a firm, unshakable position on a question and that she is inflexible once her mind is decided.

But, he added:

This is most certainly not the case. She is open, inquisitive, eager to learn, to develop her position, and to adjust her thinking. What might first appear as “dogmatic” is simply a reflection of her enthusiasm for legal questions, and her desire to engage in meaningful discussion about issues she finds engaging.

Maybe he was being too generous. I’m always wanting things to be certain, graspable, clear. Even when I find the knowledge of a firm truth absolutely torturous, I prefer it to uncertainty. Which is why I keep telling myself that I failed him; I failed, I did. I should have said something, even if he wasn’t expecting it, even if he’d forgotten me, I should have written something simple like, “I want you to know that you mattered to me.” Because he did.

Photo by scaredpoet

Never Better, a collection of essays from writers we love, is The Awl’s goodbye to 2014.

New York City, December 25, 2014

★★★★ The night noises of hard-blown rain, sounding solid against the windows, were gone. Overhead was gray, but along the western sky stretched a strip of extra-pale blue, fringed with white. The blue expanded up and east, with dark purple clouds standing against it in the distance. The children put on hoodies over their little blazers in the springlike air. There were puddles at the crosswalks, and a heavy drip was falling from a scaffold. By the end of the morning service, the whole sky was bright blue, with tiny white shreds of cloud blowing fast across it. “Windy! Windy! Windy!” the three-year-old exulted. He drew out the syllables and rocked back and forth on the shoulders with each one: “Win! Dy! Win! Dy!” More clouds rolled in as fast as the early ones had rolled out — mixed-up gray ones, with glowing spots and blue patching shining through — but the sun kept finding its way past the obstruction. Yet again, a full hour before sunset, the downriver sky was already dark orange.

Last Year's Punch

My parents picked me up in New York on their way from my hometown in suburban Pennsylvania to western Massachusetts, where we have done Thanksgiving ever since I can remember. This year was small; a few regular attendees had died. So, for the first time, the youngest generation, my generation, was entrusted with the most sacred of our family’s Thanksgiving traditions: making punch.

Thanksgiving punch is the official kickoff of the holiday; as soon as everyone arrives, construction begins. The Thanksgiving table, before it bears the weight of turkey and stuffing and potatoes, is the stage for an enormous, baroque crystal punch bowl surrounded by crystal glasses. It is an affair of much swilling and tasting and remarking on the flavor and mouthfeel and alcohol level of the punch-in-progress.

This starts at maybe 1pm, a time at which I would normally be sipping coffee and thinking about work, or making a trip to Trader Joe’s, because the lines are short and I can be sure to snag one of those Cuban sandwich wraps, which are spectacular when microwaved for around forty-five seconds, but which are sometimes gone if you try to brave the store during the crush hours of “any day after 4pm or at any point during the weekend.” But on Thanksgiving, I do not drink coffee at 1pm, and I do not go to Trader Joe’s. I make punch.

There are many rules which my cousins and uncles and I tell each other over and over again: We can’t add carbonated drinks until the end, because they’ll go flat. Remember? Remember. It must have a good, strong base of bourbon before the weirder liqueurs. It can’t be too sweet or too fruity. Don’t add too much peach nectar. It’s sweet, remember? Remember.

Soon, we agree, the base is done. For years, I assumed that decades of drinking had endowed my uncles Mark and Geoff with the ability to discern when a punch base was ready. Now I think it’s mostly that Mark and Geoff just want to get on with it.

Then we pour in wines, liquors, liqueurs, sodas, slices of orange and lemon and lime, cheap blended whiskies, thin unlabeled bottles full of light tan liquid that may turn out to be applejack or schnapps or rum from a long-ago vacation or absent friend, bottled mango and orange and cranberry juices, gross flavored brandies whose screw-top caps are encrusted with sugar and years-old basement dust. We sip, swill, and remark on the punch’s emergent quality.

“It’s getting there! It’s really getting there!” we tell each other. Eventually we are drunk enough that the punch tastes good, and is pronounced finished. At this point we are pretty much fed up with the punch anyway. The point is not to drink the punch, but to make it.

The punch bowl never been empty by the end of the night — not even the year there were 25 guests and a turkey the size of one of the Subarus that inevitably end up in the driveway of every house in the neighborhood. That’s important, both for the blood-sugar levels of the guests and for the sweetest, most nostalgic part of the punch process: the ice cube. Eighteen years ago, my uncle Geoff kept the last bit of the punch and froze it in a large Tupperware container. The following year, that giant hockey puck of punch became the ice cube in that year’s punch. As the night went on, the previous year’s punch melted into the diminishing remnants of the current year’s. This substance, this two-year punch, became the ice cube for the following year. And so on. The punch that we drank this year, the punch I helped make, has a tiny bit of the punch from 1996, when I was ten years old and not allowed to drink it, and every year since.

This year, as we gathered around the punch-creation station, my uncle Mark, with totally uncharacteristic earnestness, looked to his brother Geoff and said that it was time I and my brother and my cousins took the lead on the punch. Mark and Geoff’s father, a wonderful, warm, elfin man with permanent laugh-crinkles around his eyes, had died in early October. He was an integral part of the punch-tasting, even as he aged. The youngest of the cousins, Mark’s son Ben, was soon to graduate college, and already had a job lined up. The lives of this younger generation, myself included, were becoming real, and fixed.

In a family of northeast Jews, acerbic artists and writers and scientists and engineers, this is the way we signified that something has changed, that perhaps this Thanksgiving tradition isn’t as permanent as we’d all thought it was. This year was the smallest one in decades, maybe 12 people strong. My uncle Mark’s gesture was a submission, an acknowledgment of the fragility of life as represented by what’s in that old-fashioned punch bowl. At the time it seemed unexpected and sad. Now it feels a little crushing.

But at least now we know how to make the punch.

Never Better, a collection of essays from writers we love, is The Awl’s goodbye to 2014.

The Plath Resolution

For the past year and a half I’ve been going to yoga every Friday morning. Before this I’d done maybe a handful of classes and every one had left me in a barbed, mutinous mood. It was uncomfortable! And crowded! And on a couple occasions a little like being in a relationship where you end up shouting things like, “Don’t tell me to calm down.” Then, last year, a friend of mine started to teach classes. She’s an old friend, very smart and accepting, and when she started teaching, I was especially creaky from laptop-hunching, and it seemed like a good time to re-try. At one of my first classes, she arranged me in mountain pose — if you’ve never done yoga, mountain pose is basically standing up straight, really, that’s it — and it hurt. I should probably add right up front that I remain near this beginner level, so this isn’t going to be a story of amazing yogic transformation, although it is with some triumph that I report that after a year and half of diligent attendance, I can kind of sort of touch my toes.

The class is held in a little donation studio near downtown. It’s a morning class and a lot of nice sunlight comes in through a big window at the front of the room. There are other regulars, and once in a while someone new and glossy will swoop in like a beautiful migratory bird that’s landed in the wrong lake. I’ve gotten attached to the sign in the bathroom that says, “Please be mindful when using paper towels,” which in this particular studio comes across less like New Age passive-aggression and more as if whoever made it was at a loss to say, in a non-harsh way, STOP USING SO MANY FUCKING PAPER TOWELS.

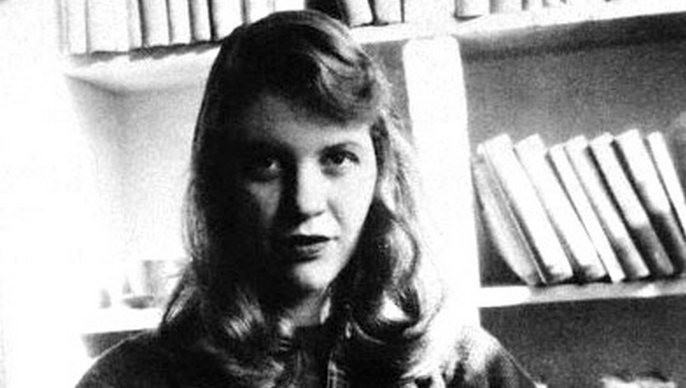

I think about Sylvia Plath a lot during yoga. I think about her during cat-cow stretches, which you do on hands and knees, arching and then rounding your back, cow to cat and back again, because of the line from “Morning Song”: “One cry, and I stumble from bed, cow-heavy and floral.” I think about her when it’s crowded and I have dickish thoughts about where other people put their mats. (Imagined journal entry: “His feet were too close. Broad, encroaching, pale peach.”) And I think about her sometimes during shavasana, or corpse pose, when I’m lying under my blanket, eyes closed, trying to touch nothingness. A long time ago I was a turbulent young woman, and, like so many other turbulent young women, the way I learned to express that — the violent unhappiness, the desire to throttle forward toward some Big Nothing — was through Plath. So it’s funny sometimes to be forty-three and lying in yoga class, under a nap-time blanket, in a roomful of people under their nap-time blankets, everyone snug as mice and thinking about being corpses.

Sometimes, of course, I don’t think about Plath. I’ll spend the entire time fretting about what I’m writing that week or if where I parked was okay. Not long after I started, I went through a two-month period of being plagued by the Hamm’s Beer jingle. In case you didn’t grow up in the upper Midwest in the ’70s, this is how it goes:

From the land of sky blue waters (waters!)

From the land of pines, lofty balsams

Comes the beer refreshing

Hamm’s the beer refreshing

Hamm’s the beer refreshing (Hamm’s)

We’d get near the end of the class, the teacher would dim the lights, I’d lie back on my mat and close my eyes, thinking, “Don’t think about Hamm’s don’t think about Hamm’s don’t think about Hamm’s,” and it’d work as well as it ever works when you tell yourself to absolutely not think about something.

In her excellent essay “Black Girls Don’t Read Sylvia Plath,” Vanessa Willoughby writes about how her “environment and my fuzzy state of mind drove me into the waiting arms of Plath. We didn’t talk about depression or mental illness in my family.” She continues: “I needed a patron saint of suffering, of potential cruelly wasted. The public library wasn’t going out of their way to stock Toni Morrison or bell hooks or Angela Davis or Nikki Giovanni or Alice Walker or Lorraine Hansberry or Zora Neale Hurston by the truckload. … Why Plath? Why not? She exposed a dirty truth about depression: Sometimes it never got better. Sometimes you could be brilliant and have the world open its mouth to reveal a pearl and you still crumbled.”

I have my own Plath stack that I re-read whenever I’m feeling especially stuck and unhappy. So once, sometimes twice a year? The routine goes: Journals first, then some Plath biographies, while looking up the different poems mentioned in The Collected Poems. (The Collected Poems is arranged by year so you can jog along with her development.) There are many other things that could be rotated in too — Ariel Restored, “Johnny Panic and the Bible of Dreams,” “Ocean 1212-W,” and The Bell Jar (duh) — but I usually don’t hit those. The current biography line-up is the Anne Stevenson one, Bitter Fame; Janet Malcolm’s The Silent Woman (which deals with how Bitter Fame got written and is perfect), and Diane Middlebrook’s amazing Her Husband. After Her Husband I sometimes flip to Ted Hughes’ poems and letters, with maybe a little sleazy Google work thrown in. It’s compulsive, this ritual, and, because I’ve been doing it for so many years, ridiculous. It makes me feel like one of the poor guys who write into Dan Savage because they’ve masturbated with a death grip too long. “Dear Dan, this started when I was a teenager and now I CAN’T STOP.” But it’s also the only thing that always works to get me going again.

I feel a lot of love, affection and gratitude for Plath, mixed in with the admiration for her work. I’m not sure if I’d known her if I’d have liked her. Sometimes I think “yes,” sometimes “no.” She occupies such a central place in my mind, though, that the question mostly seems beside the point, like worrying about whether the planet Jupiter is likeable or not. (“Jupiter ate all the foie-gras in Dido Merwin’s fridge and didn’t even say thank you once.”)

There’s a lovely section in Anne Stevenson’s biography where she talks about “Poem For A Birthday,” That’s the poem that has this bit in it:

I housekeep in Time’s gut-end

Among emmets and mollusks,

Duchess of Nothing,

Hairtusk’s bride.

It’s a seven-part poem, and Stevenson shows how its sequence goes in a horseshoe from death back to life. The part I quoted comes in the swamp-y tail of the poem, where, as Stevenson writes, “a process of self-’borning’” is taking place.

This is the Plath poem I relate the most to shavasana. You sink down, you bubble back up. The Duchess of Nothing in yoga pants.

One Friday last spring, I woke up in a foul mood. No reason. I just woke up a human gargoyle. I considered skipping yoga because there was going to be a substitute teacher but talked myself into going anyway. (“Those toes aren’t going to touch themselves you know.”) It was a grey, stuffy morning, and the entire drive I was thinking a stream of fuckity-fuck-fuck gargoyle thoughts. At one point I drove past a line of Bradford pear trees in bloom, and got offended by how ugly and dirty-snowball-looking they were, and thought, “FUCK BRADFORD PEAR TREES.” And then I marched into class and my two usual mat buddies weren’t there, but it was still crowded because of a teacher training thing and everyone had their mats in random sideways positions even though staying in rows clearly allows more people to fit and the studio smelled like a lunchroom for some reason and who was that gargoyle woman with her freaking undies in a bunch about how other people arrange their mats OH THAT’S ME. (That’s part of what’s so terrible about that kind of mood — knowing you are the most hideous person in the room.) Then the teacher started class and she didn’t cue how my friend cues and she did things in a different order and she had a kind of sing-song hippie drawl and my body felt especially creaky and so I was taking the improvisational nature of her cuing as a sort of personal attack as well as a general affront against beginning yoga students everywhere. And sometimes I was sliding around my mat, and other times I was sticking to it, and at some point we were in downward facing dog and it was super uncomfortable and I thought, “FUCK GRAVITY. I mean, seriously, FUCK GRAVITY.”

Right after this, she looked up and said, “You need to make friends with gravity.” Then she looked significantly in my direction. (I continue to hope this was simply a good body-read and not ESP.)

Later we were doing cat-cow stretches, and she was asking us to add a lion’s breath with it, where you stick out your tongue and roll your eyes up in your head as you exhale, and I liked how she let herself look bizarre when she did this, just going for it, with her eyes zoink-os, and as we continued with the cat-cowing, she arched her neck up and said, in her stretched-out hippie voice:

“Sip the NECTARRRRR.”

It was really wonderful.

There’s that famous part of The Bell Jar where the character Esther says: “I saw my life branching out before me like the green fig tree in the story. From the tip of every branch, like a fat purple fig, a wonderful future beckoned and winked. One fig was a husband and a happy home and children, and another fig was a famous poet and another fig was a brilliant professor…” And so on, down the figs.

And then there’s this, from Hurston’s Their Eyes Were Watching God: “Janie saw her life like a great tree in leaf with the things suffered, things enjoyed, things done and undone. Dawn and doom were in the branches.” A few pages later, Janie’s lying in her backyard, looking up at a blossoming pear-tree and watching the bees dip in and out: “From barren brown stems to glistening leaf-buds; from the leaf-buds to snow virginity of bloom. It stirred her tremendously. How? Why?”

Then a couple decades go by and next thing you know you’re speeding past a row of trees in bloom on your way to morning yoga, thinking, “FUCK BRADFORD PEAR TREES.”

Probably my favorite things in Plath’s journals are the resolutions and to-do lists. God, I love those lists! If you chopped me open, I’d be half made of them. Here’s one:

Try a first-person story and forget John Updike and Nadine Gordimer. Forget the results, the markets. Love only what you do, and make. Learn German. Don’t let indolence, the forerunner of death, take over. Enough has happened, enough people entered your life, to make stories, many stories, even a book. So let them onto the page and let them work out their destinies.

In the morning light, all is possible; even becoming a god.

So that’s what now? Oh yes!:

• Learn German.

• Don’t let indolence, the forerunner of death, take over.

The resolve to learn German crops up for the first time while she’s an undergraduate at Smith and debating which classes to take. (Her father, dead a decade by then, was German, so it was always a loaded resolution.) During the next few years, “learn German” disappears, then re-surfaces, disappears, re-surfaces. (Diane Middlebrook points out that it comes up most when Plath was feeling stuck.) During a residency at Yaddo — where she wrote “Poem for a Birthday” but was otherwise stalled — it gets mentioned again and again:

“I haven’t done German since I came.” “Either draw or do German.” Then: “German and French would give me self respect, why dont I act on this.”

A week later: “Worked on German for two days, then let up when I wrote poems. Must keep on with it. It is hard. So are most things worth doing.” Admirable! Followed by this tumble down: “If I can’t build up pleasures in myself: seeing and learning about painting, old civilizations, birds, trees, flowers, French, German… what shall I do? … To give myself respect, I should study botany, birds and trees: get little booklets and learn them, walk out in the world. Open my eyes.” (I love that desperate little “study botany, birds and trees: get little booklets.” Get little booklets, also maybe look into enrolling in Earthsea Wizarding Academy so you can learn the true names of every flower, herb, animal, and pebble.) The entry continues with a few other ideas of how she might improve herself before she winds up at the inevitable: “Take German lessons where I am, and read French.”

Four days later: “Take hold. Study German today.”

I have my own versions of “learn German.” Resolutions and resolves I keep rattling around with, magical transformations I keep hoping for. Or, to go to Hurston’s formulation, looking at the “things done and undone” in my life and flogging myself over the “undone” column. Sometimes I can see that better self — she’s never awkward, and she somehow managed a couple babies in her thirties and wrote a couple brilliant books, and she has friends over on weekends for wonderful dinners, and she knows the names of all the birds and trees. Etc. etc. So far in this essay I’ve been trying to keep the Beginner Yoga Student thoughts to a minimum (you’re welcome!), but I’d say the most helpful thing that going to class each week has given me is a sense that a) it’s okay to have these kinds of thoughts and resolutions and b) it’s also okay to let them go. It’s going to be a New Year soon. You don’t have to learn German.

Never Better, a collection of essays from writers we love, is The Awl’s goodbye to 2014.